Leslie R. Groves Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a

Groves was promoted to

Groves was promoted to

The Manhattan Engineer District (MED) was formally established by the Chief of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold on 16 August 1942. The name was chosen by Groves and MED's district engineer, Colonel James C. Marshall. Like other engineer districts, it was named after the city where its headquarters was located, at 270 Broadway. Unlike the others, it had no geographic boundaries, only a mission: to develop an

The Manhattan Engineer District (MED) was formally established by the Chief of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold on 16 August 1942. The name was chosen by Groves and MED's district engineer, Colonel James C. Marshall. Like other engineer districts, it was named after the city where its headquarters was located, at 270 Broadway. Unlike the others, it had no geographic boundaries, only a mission: to develop an  Groves met with Major General Wilhelm D. Styer in his office at the Pentagon to discuss the details. They agreed that in order to avoid suspicion, Groves would continue to supervise the Pentagon project. He would be promoted to brigadier general, as it was felt that the title "general" would hold more sway with the academic scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Groves therefore waited until his promotion came through on 23 September 1942 before assuming his new command. His orders placed him directly under Somervell rather than Reybold, with Marshall now answerable to Groves.

Groves was given authority to sign contracts for the project from 1 September 1942. The Under Secretary of War,

Groves met with Major General Wilhelm D. Styer in his office at the Pentagon to discuss the details. They agreed that in order to avoid suspicion, Groves would continue to supervise the Pentagon project. He would be promoted to brigadier general, as it was felt that the title "general" would hold more sway with the academic scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Groves therefore waited until his promotion came through on 23 September 1942 before assuming his new command. His orders placed him directly under Somervell rather than Reybold, with Marshall now answerable to Groves.

Groves was given authority to sign contracts for the project from 1 September 1942. The Under Secretary of War,  Groves made critical decisions on prioritizing the various methods of

Groves made critical decisions on prioritizing the various methods of  In 1943, the Manhattan District became responsible for collecting

In 1943, the Manhattan District became responsible for collecting

Responsibility for

Responsibility for

Papers of Leslie Groves at the National Archives and Records Administration

Arlington National Cemetery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Groves, Leslie 1896 births 1970 deaths United States Army Corps of Engineers personnel American military engineers United States Army personnel of World War I Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Honorary companions of the Order of the Bath Manhattan Project people Military personnel from Albany, New York Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army War College alumni United States Military Academy alumni Nuclear weapons scientists and engineers Operation Alsos 20th-century American engineers Engineers from New York (state) American people of English descent American people of Welsh descent American people of French descent 20th-century American Episcopalians United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals

United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

and directed the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, a top secret research project that developed the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

The son of a U.S. Army chaplain, Groves lived at various Army posts during his childhood. In 1918, he graduated fourth in his class at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

and was commissioned into the United States Army Corps of Engineers. In 1929, he went to Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

as part of an expedition to conduct a survey for the Inter-Oceanic Nicaragua Canal. Following the 1931 Nicaraguan earthquake, Groves took over Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

's water supply system, for which he was awarded the Nicaraguan Presidential Medal of Merit. He attended the Command and General Staff School

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas, in 1935 and 1936, and the Army War College in 1938 and 1939, after which he was posted to the War Department General Staff. Groves developed "a reputation as a doer, a driver, and a stickler for duty". In 1940 he became special assistant for construction to the Quartermaster General, tasked with inspecting construction sites and checking on their progress. In August 1941, he was appointed to create the gigantic office complex for the War Department's 40,000 staff that would ultimately become the Pentagon.

In September 1942, Groves took charge of the Manhattan Project. He was involved in most aspects of the atomic bomb's development: he participated in the selection of sites for research and production at Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's po ...

; Los Alamos, New Mexico

Los Alamos (, meaning ''The Poplars'') is a census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, that is recognized as one of the development and creation places of the Nuclear weapon, atomic bomb—the primary objective of ...

; and Hanford, Washington. He directed the enormous construction effort, made critical decisions on the various methods of isotope separation, acquired raw materials, directed the collection of military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

on the German nuclear energy project and helped select the cities in Japan that were chosen as targets. Groves wrapped the Manhattan Project in security, but spies working within the project were able to pass some of its most important secrets to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

After the war, Groves remained in charge of the Manhattan Project until responsibility for nuclear weapons production was handed over to the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

in 1947. He then headed the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, which had been created to control the military aspects of nuclear weapons. He was given a dressing down by the Chief of Staff of the Army, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, on the basis of various complaints, and told that he would never be appointed Chief of Engineers. Three days later, Groves announced his intention to leave the Army. He was promoted to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

just before his retirement on 29 February 1948 in recognition of his leadership of the bomb program. By a special act of Congress, his date of rank was backdated to 16 July 1945, the date of the Trinity nuclear test. He went on to become a vice president at Sperry Rand

Sperry Corporation was a major American equipment and electronics company whose existence spanned more than seven decades of the 20th century. Sperry ceased to exist in 1986 following a prolonged hostile takeover bid engineered by Burroughs ...

.

Early life

Leslie Richard Groves Jr. was born inAlbany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

, on 17 August 1896, the third son of four children of a pastor

A pastor (abbreviated to "Ps","Pr", "Pstr.", "Ptr." or "Psa" (both singular), or "Ps" (plural)) is the leader of a Christianity, Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutherani ...

, Leslie Richard Groves Sr., and his wife Gwen née Griffith. He was half Welsh and half English, with some French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

ancestors who came to the United States in the 17th century. Leslie Groves Sr. resigned as pastor of the Sixth Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

church in Albany in December 1896 to become a United States Army chaplain. He was posted to the 14th Infantry at Vancouver Barracks in Washington state

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

in 1897.

Following the outbreak of the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

in 1898, Chaplain Groves was sent to Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

with the 8th Infantry. On returning to Vancouver Barracks, he was ordered to rejoin the 14th Infantry in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. Service in the Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

and the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

followed. The 14th Infantry returned to the United States in 1901 and moved to Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The family relocated to there from Vancouver, then moved to Fort Hancock, New Jersey, and returned to Vancouver in 1905. Chaplain Groves was hospitalized with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

at Fort Bayard in 1905. He decided to settle in southern California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

and bought a house in Altadena. His next posting was to Fort Apache, Arizona

Fort Apache () is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated community in Navajo County, Arizona, Navajo County, Arizona, United States. Today's settlement of Fort Apache incorporates elements of the original U.S. Cavalry post Fort Apache Historic P ...

. The family spent their summers there and returned to Altadena where the children attended school.

In 1911, Chaplain Groves was ordered to return to the 14th Infantry, which was now stationed at Fort William Henry Harrison, Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

. At Fort Harrison, the younger Groves met Grace (Boo) Wilson, the daughter of Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Richard Hulbert Wilson, a career Army officer who had served with Chaplain Groves during the 8th Infantry's posting to Cuba. In 1913, the 14th Infantry moved once more, this time to Fort Lawton

Fort Lawton was a United States Army Military base, post located in the Magnolia, Seattle, Washington, Magnolia neighborhood of Seattle, Washington (state), Washington overlooking Puget Sound. In 1973 a large majority of the property, 534 acre ...

in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

, Washington.

Groves entered Queen Anne High School in 1913, and graduated in 1914. While completing high school, he enrolled in courses at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

, in anticipation of attempting to gain an appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. He earned a nomination from the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, which allowed him to compete for a vacancy, but did not score a high enough mark on the examination to be admitted. Charles W. Bell from California's 9th congressional district nominated Groves as an alternate, but the principal nominee accepted. Instead, Groves enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

(MIT) and planned to re-take the West Point entrance exam. In 1916, Groves tested again, attained a passing score, and was accepted. He later said "Entering West Point fulfilled my greatest ambition. I had been brought up in the Army, and in the main had lived on Army posts all my life."

Groves's class entered West Point on 15 June 1916. The United States declaration of war on Germany in April 1917 led to their program of instruction being shortened as the War Emergency Course (WEC), which graduated on 1 November 1918, a year and a half ahead of schedule. Groves finished fourth in his class, which earned him a commission as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers, the first choice of most high ranking cadets.

At MIT he had played tennis informally, but at West Point he could not skate for ice hockey, did not like basketball, and was not good enough for baseball or track. So football was his only sport. He said that "I was the number two center but was on the bench most of the time as in those days you didn't have substitutes and normally the number one played the whole game. I was not very heavy, and today would be considered too light to play at all".

Between the wars

After the traditional month's leave following graduation from West Point, Groves reported to Camp A. A. Humphreys,Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, in December 1918, where he was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

on 1 May 1919. He was sent to France in June on an educational tour of the European battlefields of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. After returning from Europe, Groves became a student officer at the Engineer School at Camp Humphreys in September 1919. On graduation he was posted to the 7th Engineers at Fort Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, as a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members ...

commander.

He returned to Camp Humphreys in February 1921 for the Engineer Basic Officers' Course. On graduation in August 1921, he was posted to the 4th Engineers, stationed at Camp Lewis, Washington. He was then posted to Fort Worden in command of a survey detachment. This was close to Seattle, so he was able to pursue his courtship of Grace Wilson, who had become a kindergarten teacher. They were married in St. Clement's Episcopal Church in Seattle on 10 February 1922. Their marriage produced two children: a son, Richard Hulbert, born in 1923, and a daughter, Gwen, born in 1928.

In November 1922, Groves received his first overseas posting, as a company commander with the 3rd Engineers at the Schofield Barracks in Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

. He earned a commendation for his work there, constructing a trail from Kahuku to Pupukea. In November 1925 he was posted to Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

, as an assistant to the District Engineer, Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Julian Schley. Groves's duties included opening the channel at Port Isabel and supervising dredging operations in Galveston Bay. In 1927 he became commander of Company D, 1st Engineers, at Fort DuPont, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

.

During the New England Flood of November 1927 he was sent to Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

, to assist with a detachment of the 1st Engineers. After a pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, is a bridge that uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the support ...

they constructed was swamped and swept away by the flood waters, Groves was accused of negligence. A month later Groves and several of his men were seriously injured, one fatally, when a block of TNT prematurely detonated. Groves's superior wrote a critical report on him, but the Chief of Engineers, Major General Edgar Jadwin, interceded, attributing blame to Groves's superiors instead. Groves was returned to Fort DuPont.

In 1929, Groves departed for Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

in charge of a company of the 1st Engineers as part of an expedition whose purpose was to conduct a survey for the Inter-Oceanic Nicaragua Canal. Following the 1931 Nicaragua earthquake

The 1931 Nicaragua earthquake devastated Nicaragua's capital city of Managua on 31 March 1931. It had a moment magnitude of 6.1 and a maximum MSK intensity of VI (''Strong''). Between 1,000 and 2,450 people were killed. A major fire started and ...

, Groves took over responsibility for Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

's water supply system, for which he was awarded the Nicaraguan Presidential Medal of Merit. Groves was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 20 October 1934. He attended the Command and General Staff School

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

, in 1935 and 1936, after which he was posted to Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City, Missouri, abbreviated KC or KCMO, is the largest city in the U.S. state of Missouri by List of cities in Missouri, population and area. The city lies within Jackson County, Missouri, Jackson, Clay County, Missouri, Clay, and Pl ...

, as assistant to the commander of the Missouri River Division. In 1938 and 1939 he attended the Army War College. On 1 July 1939, he was posted to the War Department General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

in Washington, D.C.

World War II

Construction Division

Groves was promoted to

Groves was promoted to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 1 July 1940. Three weeks later, he became special assistant for construction to the Quartermaster General, Major General Edmund B. Gregory. The two men had known each other a long time, as Groves's father was a close friend of Gregory's. At this point, the US Army was about to embark on a national mobilization, and it was the task of the Construction Division of the Quartermaster Corps

Following is a list of quartermaster corps, military units, active and defunct, with logistics duties:

* Egyptian Army Quartermaster Corps - see Structure of the Egyptian Army

* Hellenic Army Quartermaster Corps (''Σώμα Φροντιστών ...

to prepare the necessary accommodations and training facilities for the vast army that would be created. The enormous construction program had been dogged by bottlenecks, shortages, delays, spiralling costs, and poor living conditions at the construction sites. Newspapers began publishing accounts charging the Construction Division with incompetence, ineptitude, and inefficiency. Groves, who "had a reputation as a doer, a driver, and a stickler for duty", was one of a number of engineer officers brought in to turn the project around. He was tasked with inspecting construction sites and checking on their progress.

On 12 November 1940, Gregory asked Groves to take over command of the Fixed Fee Branch of the Construction Division as soon as his promotion to colonel came through. Groves assumed his new rank and duties on 14 November 1940. Groves later recalled:

Groves instituted a series of reforms. He installed phone lines for the Supervising Construction Quartermasters, demanded weekly reports on progress, ordered that reimbursement vouchers be processed within a week, and sent expediters to sites reporting shortages. He ordered his contractors to hire whatever special equipment they needed and to pay premium prices if necessary to guarantee quick delivery. Instead of allowing construction of camps to proceed in whatever order the contractors saw fit, Groves laid down priorities for completion of camp facilities, so that the troops could begin moving in even while construction was still under way.

By mid-December, the worst of the crisis was over. Over half a million men had been mobilized and essential accommodations and facilities for two million men were 95 per cent complete. Between 1 July 1940 and 10 December 1941, the Construction Division let contracts worth $1,676,293,000 ($ with inflation), of which $1,347,991,000 ($ with inflation), or about 80 per cent, were fixed-fee contracts.

On 19 August 1941, Groves was summoned to a meeting with the head of the Construction Division, Brigadier General Brehon B. Somervell. In attendance were Captain Clarence Renshaw, one of Groves's assistants; Major Hugh J. Casey, the chief of the Construction Division's Design and Engineering Section; and George Bergstrom, a former president of the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C. AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach progr ...

. Casey and Bergstrom had designed an enormous office complex to house the War Department's 40,000 staff together in one building, a five-story, five-sided structure, which would ultimately become the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

.

The Pentagon had a total square footage of – twice that of the Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is a 102-story, Art Deco-style supertall skyscraper in the Midtown South neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its n ...

– making it the largest office building in the world. The estimated cost was $35 million ($ with inflation), and Somervell wanted of floor space available by 1 March 1942. Bergstrom became the architect-engineer with Renshaw in charge of construction, reporting directly to Groves. At its peak the project employed 13,000 persons. By the end of April, the first occupants were moving in and of space was ready by the end of May. In the end, the project cost some $63 million ($ with inflation).

Groves steadily overcame one crisis after another, dealing with strikes, shortages, competing priorities and engineers who were not up to their tasks. He worked six days a week in his office in Washington, D.C. During the week he would determine which project was in the greatest need of personal attention and pay it a visit on Sunday. Groves later recalled that he was "hoping to get to a war theater so I could find a little peace."

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Engineer District (MED) was formally established by the Chief of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold on 16 August 1942. The name was chosen by Groves and MED's district engineer, Colonel James C. Marshall. Like other engineer districts, it was named after the city where its headquarters was located, at 270 Broadway. Unlike the others, it had no geographic boundaries, only a mission: to develop an

The Manhattan Engineer District (MED) was formally established by the Chief of Engineers, Major General Eugene Reybold on 16 August 1942. The name was chosen by Groves and MED's district engineer, Colonel James C. Marshall. Like other engineer districts, it was named after the city where its headquarters was located, at 270 Broadway. Unlike the others, it had no geographic boundaries, only a mission: to develop an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. Marshall had the authority of a division engineer head and reported directly to Reybold.

Although Reybold was satisfied with the progress being made, Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II, World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almo ...

was less so. He felt that aggressive leadership was required, and suggested the appointment of a prestigious officer as overall project director. Somervell, now Chief of Army Service Forces, recommended Groves. Somervell met Groves outside the hearing room where Groves had been testifying before a United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

committee on military housing and informed him that "The Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

has selected you for a very important assignment, and the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

has approved the selection ... If you do the job right, it will win the war." Groves could not hide his disappointment at not receiving a combat assignment: "Oh, that thing," he replied.

Groves met with Major General Wilhelm D. Styer in his office at the Pentagon to discuss the details. They agreed that in order to avoid suspicion, Groves would continue to supervise the Pentagon project. He would be promoted to brigadier general, as it was felt that the title "general" would hold more sway with the academic scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Groves therefore waited until his promotion came through on 23 September 1942 before assuming his new command. His orders placed him directly under Somervell rather than Reybold, with Marshall now answerable to Groves.

Groves was given authority to sign contracts for the project from 1 September 1942. The Under Secretary of War,

Groves met with Major General Wilhelm D. Styer in his office at the Pentagon to discuss the details. They agreed that in order to avoid suspicion, Groves would continue to supervise the Pentagon project. He would be promoted to brigadier general, as it was felt that the title "general" would hold more sway with the academic scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Groves therefore waited until his promotion came through on 23 September 1942 before assuming his new command. His orders placed him directly under Somervell rather than Reybold, with Marshall now answerable to Groves.

Groves was given authority to sign contracts for the project from 1 September 1942. The Under Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson

Robert Porter Patterson Sr. (February 12, 1891 – January 22, 1952) was an American judge who served as United States Under Secretary of War, Under Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and US Secretary of War, U.S. Secretary of ...

, retrospectively delegated his authority from the President under the War Powers Act of 1941 in a memorandum to Groves dated 17 April 1944. Groves delegated the authority to Kenneth Nichols, except for contracts of $5 million or more that required his authority. The written authority was only given in 1944 when Nichols was about to sign a contract with Du Pont, and it was found that Nichols's original authority to sign project contracts for Marshall was based on a verbal authority from Styer, and Nichols only had the low delegated authority of a divisional engineer.

Groves soon decided to establish his project headquarters on the fifth floor of the New War Department Building, now known as the Harry S Truman Building, in Washington, D.C., where Marshall had maintained a liaison office. In August 1943, the MED headquarters moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's po ...

, but the name of the district did not change.

Construction accounted for roughly 90 percent of the Manhattan Project's total cost. The day after Groves took over, he and Marshall took a train to Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

to inspect the site that Marshall had chosen for the proposed production plant at Oak Ridge. Groves was suitably impressed with the site, and steps were taken to condemn the land. Protests, legal appeals, and congressional inquiries were to no avail. By mid-November U.S. Marshals were tacking notices to vacate on farmhouse doors, and construction contractors were moving in.

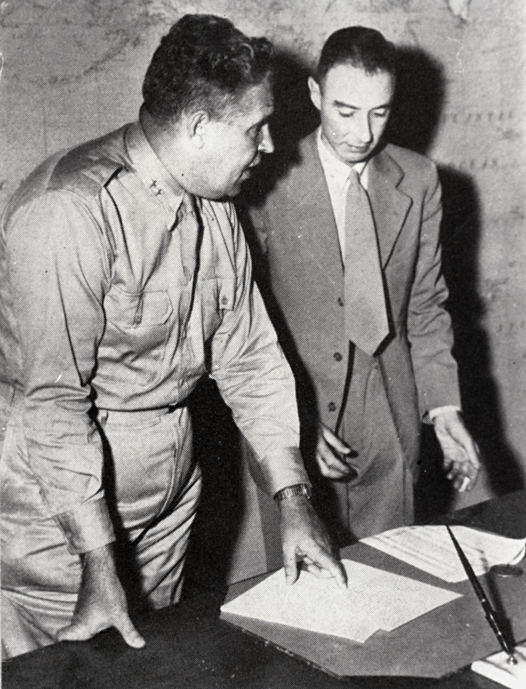

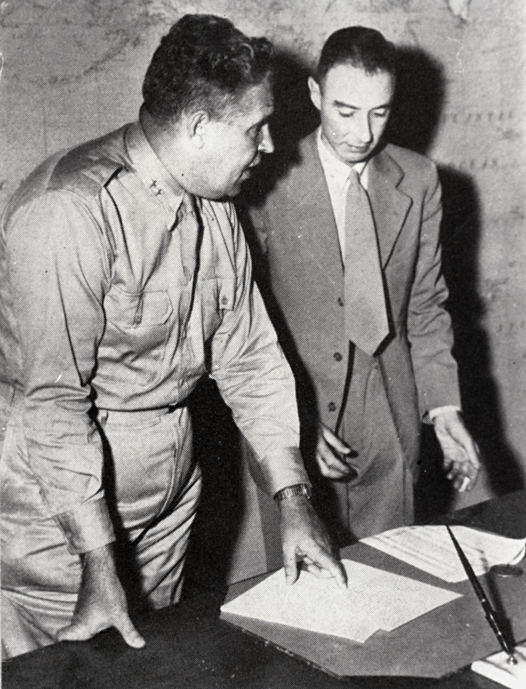

Meanwhile, Groves had met with J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World ...

, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, and discussed the creation of a laboratory where the bomb could be designed and tested. Groves was impressed with the breadth of Oppenheimer's knowledge. He had a long conversation on a train after a meeting in Chicago on October 15, when Groves invited Oppenheimer to join Marshall and Nichols on the 20th Century Limited train returning to New York. After dinner on the train they discussed the project while squeezed into Nichols's one-person roomette, and when Oppenheimer left the train at Buffalo, Nichols had no doubt that he should direct the new lab. Groves saw that Oppenheimer thoroughly understood the issues involved in setting up a laboratory in a remote area. These were features that Groves found lacking in other scientists, and he knew that broad knowledge would be vital in an interdisciplinary project that would involve not just physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, but chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

, ordnance, and engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

.

In October 1942 Groves and Oppenheimer inspected sites in New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, where they selected a suitable location for the laboratory at Los Alamos. Unlike Oak Ridge, the ranch school at Los Alamos, along with of surrounding forest and grazing land, was soon acquired. Groves also detected in Oppenheimer something that many others did not, an "overweening ambition" which Groves reckoned would supply the drive necessary to push the project to a successful conclusion. Groves became convinced that Oppenheimer was the best and only man to run the laboratory.

Few agreed with him in 1942. Oppenheimer had little administrative experience and, unlike other potential candidates, no Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

. There was also concern about whether Oppenheimer was a security risk, as many of his associates were communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

s, including his brother Frank Oppenheimer, his wife Katherine Oppenheimer, and his girlfriend Jean Tatlock. Oppenheimer's Communist Party connections soon came to light, but Groves personally waived the security requirements and issued Oppenheimer a clearance on 20 July 1943. Groves's faith in Oppenheimer was ultimately justified. Oppenheimer's inspirational leadership fostered practical approaches to designing and building bombs. Asked years later why Groves chose him, Oppenheimer replied that the general "had a fatal weakness for good men." Isidor Rabi considered the appointment "a real stroke of genius on the part of General Groves, who was not generally considered to be a genius ..."

Groves made critical decisions on prioritizing the various methods of

Groves made critical decisions on prioritizing the various methods of isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

and acquiring raw materials needed by the scientists and engineers. By the time he assumed command of the project, it was evident that the AA-3 priority rating that Marshall had obtained was insufficient. The top ratings were AA-1 through AA-4 in descending order, although there was also a special AAA rating reserved for emergencies. Ratings AA-1 and AA-2 were for essential weapons and equipment, so Colonel Lucius D. Clay, the deputy chief of staff at Services and Supply for requirements and resources, felt that the highest rating he could assign was AA-3, although he was willing to provide an AAA rating on request for critical materials to remove bottlenecks. Groves went to Donald M. Nelson, the chairman of the War Production Board and, after threatening to take the matter to the President, obtained a AAA priority for the Manhattan project. It was agreed that the AA-3 priority would still be used where possible.

The Combined Development Trust was established by the governments of the United Kingdom, United States and Canada in June 1944, with Groves as its chairman, to procure uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

and thorium

Thorium is a chemical element; it has symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is a weakly radioactive light silver metal which tarnishes olive grey when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft, malleable, and ha ...

ores on international markets. In 1944, the trust purchased of uranium oxide ore from companies operating mines in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

. In order to avoid briefing the Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau Jr., on the project, a special account not subject to the usual auditing and controls was used to hold Trust monies. Between 1944 and the time he resigned from the Trust in 1947, Groves deposited a total of $37.5 million into the Trust's account.

Worried by the heavy losses occurring during the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

, in late December 1944 President Roosevelt requested atomic bombs be dropped on Germany during his only meeting with Groves during the war. Groves informed him the first workable bomb was months away.

In 1943, the Manhattan District became responsible for collecting

In 1943, the Manhattan District became responsible for collecting military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

on Axis atomic research. Groves created Operation Alsos, special intelligence teams that would follow in the wake of the advancing armies, rounding up enemy scientists and collecting what technical information and technology they could. Alsos teams ultimately operated in Italy, France and Germany. The security system resembled that of other engineer districts. The Manhattan District organized its own counterintelligence which gradually grew in size and scope, but strict security measures failed to prevent the Soviets from conducting a successful espionage program that stole some of its most important secrets.

Groves met with General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Henry H. Arnold, the Chief of U.S. Army Air Forces, in March 1944 to discuss the delivery of the finished bombs to their targets. Groves was hoping that the Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the Bo ...

would be able to carry the finished bombs. The 509th Composite Group was duly activated on 17 December 1944 at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

, under the command of Colonel Paul W. Tibbets. A joint Manhattan District – USAAF targeting committee was established to determine which cities in Japan should be targets. It recommended Kokura

is an ancient Jōkamachi, castle town and the center of modern Kitakyushu, Japan. Kokura is also the name of the Kokura Station, penultimate station on the southbound San'yō Shinkansen line, which is owned by JR West. Ferries connect Kokura ...

, Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

, Niigata, and Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

.

At this point, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry L. Stimson intervened, announcing that he would be making the targeting decision, and that he would not authorize the bombing of Kyoto. Groves attempted to get him to change his mind several times and Stimson refused every time. Kyoto had been the capital of Japan

The capital of Japan is Tokyo."About Japan"

The Government of Japan. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

for centuries, and was of great cultural and religious significance. In the end, Groves asked Arnold to remove Kyoto not just from the list of nuclear targets, but from targets for conventional bombing as well. The Government of Japan. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

was substituted for Kyoto as a target.

Groves was promoted to temporary major general on 9 March 1944. After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki became public knowledge, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. His citation read:

Groves had previously been nominated for the Distinguished Service Medal for his work on the Pentagon, but to avoid drawing attention to the Manhattan Project, it had not been awarded at the time. After the war, the Decorations Board decided to change it to a Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

. In recognition of his work on the project, the Belgian government made him a Commander of the Order of the Crown and the British government made him an honorary Companion of the Order of the Bath.

After the war

Responsibility for

Responsibility for nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

and nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

was transferred from the Manhattan District to the Atomic Energy Commission on 1 January 1947. On 29 January 1947, the Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson

Robert Porter Patterson Sr. (February 12, 1891 – January 22, 1952) was an American judge who served as United States Under Secretary of War, Under Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and US Secretary of War, U.S. Secretary of ...

, and the Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

, James V. Forrestal, issued a joint directive creating the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP) to control the military aspects of nuclear weapons. Groves was appointed its chief on 28 February 1947. In April, AFSWP moved from the New War Department Building to the fifth floor of the Pentagon. Groves had already made a start on the new mission by creating Sandia Base in 1946.

The Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, met with Groves on 30 January 1948 to evaluate his performance. Eisenhower recounted a long list of complaints about Groves pertaining to his rudeness, arrogance, insensitivity, contempt for the rules, and maneuvering for promotion out of turn. Eisenhower made it clear that Groves would never become Chief of Engineers.

Groves realized that in the rapidly shrinking postwar military he would not be given any assignment similar in importance to the one he had held in the Manhattan Project, as such posts would go to combat commanders returning from overseas, and he decided to leave the Army. In recognition of his leadership of the Manhattan Project, he received an honorary promotion to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

by special Act of Congress, effective 24 January 1948, just before his retirement on 29 February 1948. His date of rank was backdated to 16 July 1945, the date of the Trinity nuclear test.

Later life

Groves went on to become a vice president atSperry Rand

Sperry Corporation was a major American equipment and electronics company whose existence spanned more than seven decades of the 20th century. Sperry ceased to exist in 1986 following a prolonged hostile takeover bid engineered by Burroughs ...

, an equipment and electronics firm, and moved to Darien, Connecticut

Darien ( ) is a coastal town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. With a population of 21,499 and a land area of just under , it is the smallest town on Connecticut's Gold Coast (Connecticut), Gold Coast.

Situated on the Long Island ...

, in 1948, and retired at age 65 in 1961. He also served as president of the West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

alumni organization, the ''Association of Graduates''. He presented General of the Army Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

the Sylvanus Thayer Award in 1962, which was the occasion of MacArthur's famous ''Duty, Honor, Country'' speech to the U.S. Military Academy Corps of Cadets. In retirement, Groves wrote an account of the Manhattan Project entitled ''Now It Can Be Told'', originally published in 1962. In 1964, he moved back to Washington, D.C.

Groves suffered a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

caused by chronic calcification

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature M ...

of the aortic valve

The aortic valve is a valve in the heart of humans and most other animals, located between the left ventricle and the aorta. It is one of the four valves of the heart and one of the two semilunar valves, the other being the pulmonary valve. ...

on 13 July 1970. He was rushed to Walter Reed Army Medical Center

The Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC), officially known as Walter Reed General Hospital (WRGH) until 1951, was the United States Army, U.S. Army's flagship medical center from 1909 to 2011. Located on in Washington, D.C., it served more ...

in Washington, D.C., where he died that night at age 73. A funeral service was held in the chapel at Fort Myer, Virginia, after which Groves was interred in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

next to his brother Allen, who had died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

in 1916.

Legacy

Groves is memorialized at a namesake park along theColumbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

, near the Hanford Site in Richland, Washington

Richland () is a city in Benton County, Washington, United States. It is located in southeastern Washington at the confluence of the Yakima River, Yakima and the Columbia River, Columbia Rivers. As of the 2020 census, the city's population was ...

. At the United States Military Academy, the LTG Leslie R. Groves Award is awarded to the cadet with the highest GPA in major classes associated with nuclear engineering.

The 1980 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

series, '' Oppenheimer'', featured Manning Redwood as Groves. The same year, he was played by Richard Herd

Richard Thomas Herd Jr. (September 26, 1932 – May 26, 2020) was an American actor appearing in numerous supporting, recurring, and guest roles in television series and occasional film roles from the 1970s to the 2010s. He was well known in the ...

in the American television movie, '' Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb''. In the 1989 film '' Fat Man and Little Boy'', he was portrayed by Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, philanthropist, and activist. He was the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Paul Newman, numerous awards ...

, and in the made-for-TV movie of the same year, '' Day One'', by Brian Dennehy. In 1995, Groves was portrayed by Richard Masur

Richard Masur (born November 20, 1948) is an American character actor who has appeared in more than 40 films. From 1995 to 1999, he served two terms as president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). He is best known for playing David Kane on '' One ...

in the Japanese-Canadian made-for-television movie ''Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

''. He was portrayed by Eric Owens in the 2007 Lyric Opera of Chicago

Lyric Opera of Chicago is an American opera company based in Chicago, Illinois. The company was founded in Chicago in 1954, under the name 'Lyric Theatre of Chicago' by Carol Fox (Chicago opera), Carol Fox, Nicola Rescigno and Lawrence Kelly, w ...

's work '' Doctor Atomic''. The opera follows Oppenheimer, Groves, Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

and others in the days preceding the Trinity test. Groves is played by Matt Damon

Matthew Paige Damon ( ; born October 8, 1970) is an American actor, film producer, and screenwriter. He was ranked among ''Forbes'' most bankable stars in 2007, and in 2010 was one of the highest-grossing actors of all time. He has received va ...

in Christopher Nolan

Sir Christopher Edward Nolan (born 30 July 1970) is a British and American filmmaker. Known for his Cinema of the United States, Hollywood Blockbuster (entertainment), blockbusters with complex storytelling, he is considered a leading filmma ...

's 2023 film '' Oppenheimer''.

Dates of rank

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* 11 hours of interviews with Groves on the Manhattan Project. * Memorandum for the Secretary of War, Groves describes the firstTrinity (nuclear test)

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

in New Mexico.

Papers of Leslie Groves at the National Archives and Records Administration

Arlington National Cemetery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Groves, Leslie 1896 births 1970 deaths United States Army Corps of Engineers personnel American military engineers United States Army personnel of World War I Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Honorary companions of the Order of the Bath Manhattan Project people Military personnel from Albany, New York Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army War College alumni United States Military Academy alumni Nuclear weapons scientists and engineers Operation Alsos 20th-century American engineers Engineers from New York (state) American people of English descent American people of Welsh descent American people of French descent 20th-century American Episcopalians United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals