Lead () is a

chemical element

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its ...

; it has

symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

Pb (from

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

) and

atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

82. It is a

heavy metal that is

denser than most common materials. Lead is

soft and

malleable

Ductility refers to the ability of a material to sustain significant plastic deformation before fracture. Plastic deformation is the permanent distortion of a material under applied stress, as opposed to elastic deformation, which is reversi ...

, and also has a relatively low

melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

. When freshly cut, lead is a shiny gray with a hint of blue. It

tarnish

Tarnish is a thin layer of corrosion that forms over copper, brass, aluminum, magnesium, neodymium and other similar metals as their outermost layer undergoes a chemical reaction. Tarnish does not always result from the sole effects of oxygen in ...

es to a dull gray color when exposed to air. Lead has the highest atomic number of any

stable element and three of its

isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

s are endpoints of major nuclear

decay chain

In nuclear science a decay chain refers to the predictable series of radioactive disintegrations undergone by the nuclei of certain unstable chemical elements.

Radioactive isotopes do not usually decay directly to stable isotopes, but rather ...

s of heavier elements.

Lead is a relatively unreactive

post-transition metal

The metallic elements in the periodic table located between the transition metals to their left and the chemically weak nonmetallic metalloids to their right have received many names in the literature, such as post-transition metals, poor metal ...

. Its weak metallic character is illustrated by its

amphoteric

In chemistry, an amphoteric compound () is a molecule or ion that can react both as an acid and as a base. What exactly this can mean depends on which definitions of acids and bases are being used.

Etymology and terminology

Amphoteric is d ...

nature; lead and

lead oxide

Lead oxides are a group of inorganic compounds with formulas including lead (Pb) and oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), gr ...

s react with

acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Br├ĖnstedŌĆōLowry acidŌĆōbase theory, Br├ĖnstedŌĆōLowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

s and

bases, and it tends to form

covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

s.

Compounds of lead

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive stru ...

are usually found in the +2

oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical Electrical charge, charge of an atom if all of its Chemical bond, bonds to other atoms are fully Ionic bond, ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons ...

rather than the +4 state common with lighter members of the

carbon group

The carbon group is a group (periodic table), periodic table group consisting of carbon (C), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), and flerovium (Fl). It lies within the p-block.

In modern International Union of Pure and Applied Ch ...

. Exceptions are mostly limited to

organolead compounds. Like the lighter members of the group, lead tends to

bond with itself; it can form chains and polyhedral structures.

Since lead is easily extracted from its

ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the concentration ...

s, prehistoric people in the Near East

were aware of it.

Galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

is a principal ore of lead which often bears silver. Interest in silver helped initiate widespread extraction and use of lead in

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

. Lead production declined after the

fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

and did not reach comparable levels until the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. Lead played a crucial role in the development of the

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

, as

movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable Sort (typesetting), components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric charac ...

could be relatively easily cast from lead alloys. In 2014, the annual global production of lead was about ten million tonnes, over half of which was from recycling. Lead's high density, low melting point,

ductility

Ductility refers to the ability of a material to sustain significant plastic Deformation (engineering), deformation before fracture. Plastic deformation is the permanent distortion of a material under applied stress, as opposed to elastic def ...

and relative inertness to

oxidation

Redox ( , , reductionŌĆōoxidation or oxidationŌĆōreduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

make it useful. These properties, combined with its relative abundance and low cost, resulted in its extensive use in

construction

Construction are processes involved in delivering buildings, infrastructure, industrial facilities, and associated activities through to the end of their life. It typically starts with planning, financing, and design that continues until the a ...

,

plumbing

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses piping, pipes, valves, piping and plumbing fitting, plumbing fixtures, Storage tank, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. HVAC, Heating and co ...

,

batteries,

bullets

A bullet is a Kinetic energy weapon, kinetic projectile, a component of firearm ammunition that is Shooting, shot from a gun barrel. They are made of a variety of materials, such as copper, lead, steel, polymer, rubber and even wax; and are made ...

,

shots,

weights,

solder

Solder (; North American English, NA: ) is a fusible alloy, fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces aft ...

s,

pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85ŌĆō99%), antimony (approximately 5ŌĆō10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. In the past, it was an alloy of tin and lead, but most modern pewter, in order to prevent lead poi ...

s,

fusible alloy

A fusible alloy is a metal alloy capable of being easily fused, i.e. easily meltable, at relatively low temperatures. Fusible alloys are commonly, but not necessarily, eutectic alloys.

Sometimes the term "fusible alloy" is used to describe alloy ...

s,

lead paint

Lead paint or lead-based paint is paint containing lead. As pigment, lead(II) chromate (, "chrome yellow"), lead(II,IV) oxide, (, "red lead"), and lead(II) carbonate (, "white lead") are the most common forms.. Lead is added to paint to acceler ...

s,

leaded gasoline

Gasoline (North American English) or petrol (Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish, and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When formulate ...

, and

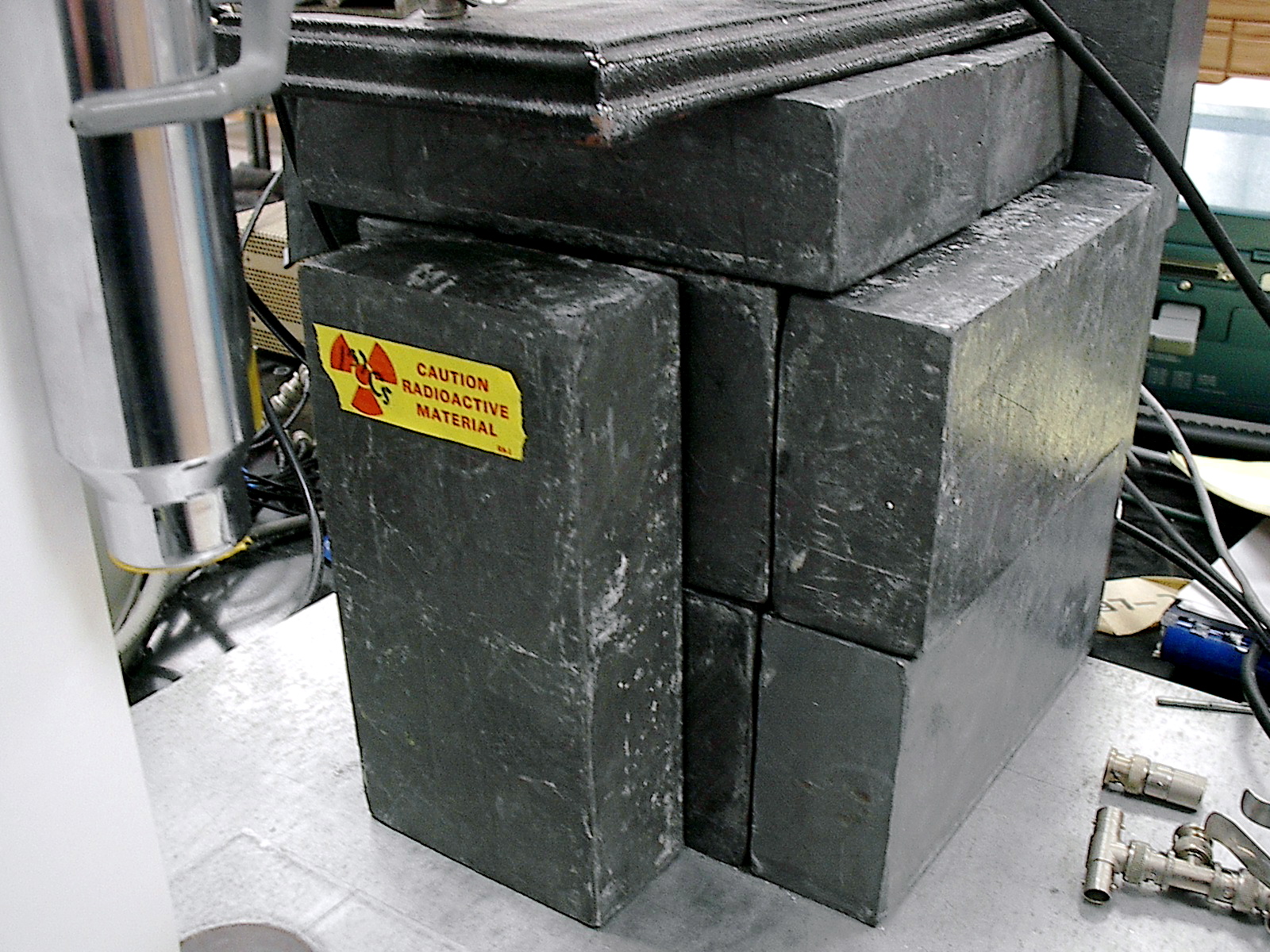

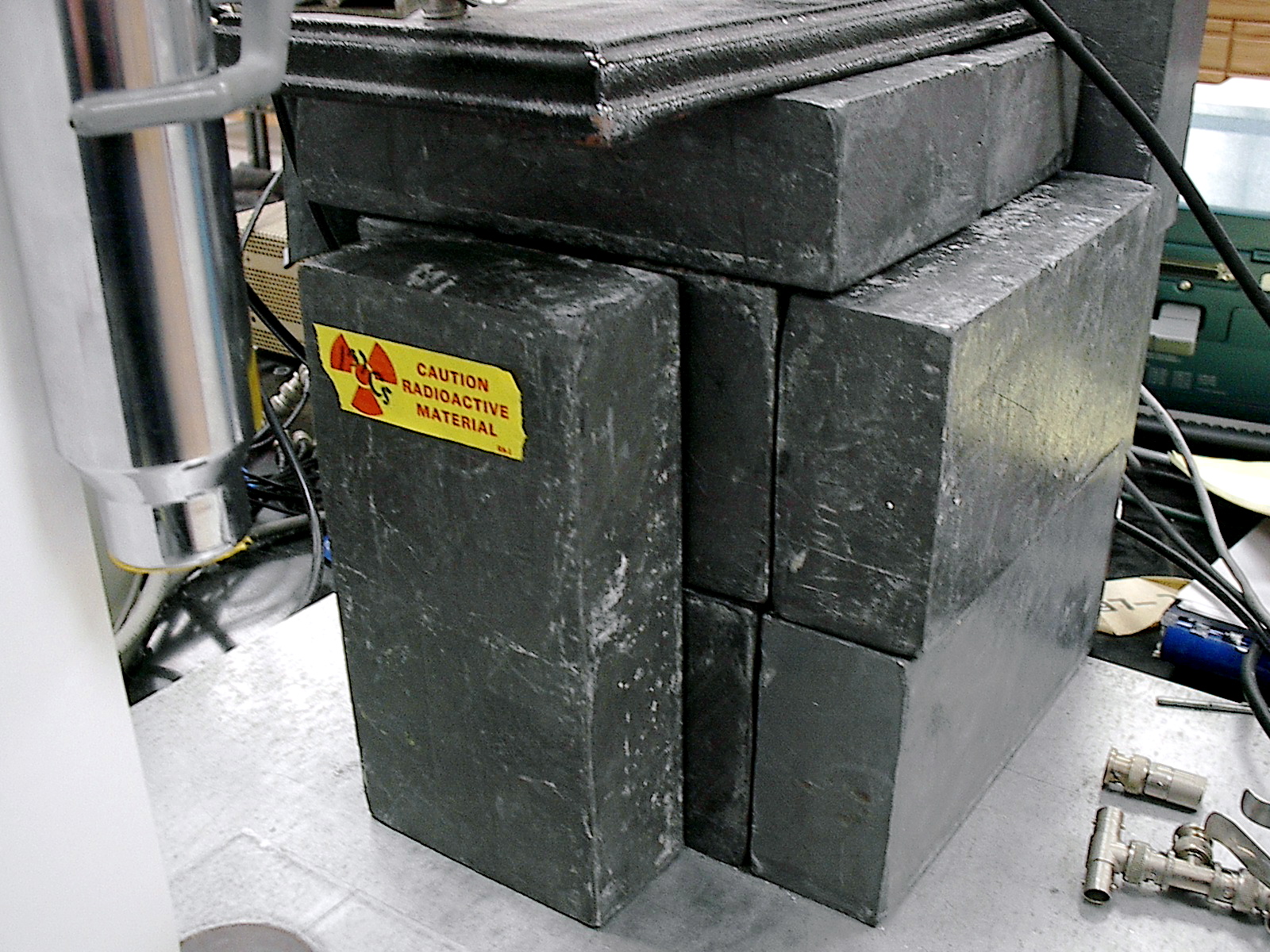

radiation shielding.

Lead is a

neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nervous tissue, nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insult (medical), insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function ...

that accumulates in soft tissues and bones. It damages the nervous system and interferes with the function of biological

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s, causing

neurological disorder

Neurological disorders represent a complex array of medical conditions that fundamentally disrupt the functioning of the nervous system. These disorders affect the brain, spinal cord, and nerve networks, presenting unique diagnosis, treatment, and ...

s ranging from behavioral problems to brain damage, and also affects general health, cardiovascular, and renal systems.

Lead's toxicity was first documented by ancient Greek and Roman writers, who noted some of the symptoms of

lead poisoning

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, infertility, numbness and paresthesia, t ...

, but became widely recognized in Europe in the late 19th century.

Physical properties

Atomic

A lead

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

has 82

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s, arranged in an

electron configuration

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the electron configuration is the distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule (or other physical structure) in atomic or molecular orbitals. For example, the electron configuration of the neon ato ...

of [

Xe]4f

145d

106s

26p

2. The sum of lead's first and second

ionization energies

In physics and chemistry, ionization energy (IE) is the minimum energy required to remove the most loosely bound electron of an isolated gaseous atom, positive ion, or molecule. The first ionization energy is quantitatively expressed as

:X(g) ...

ŌĆöthe total energy required to remove the two 6p electronsŌĆöis close to that of

tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

, lead's upper neighbor in the

carbon group

The carbon group is a group (periodic table), periodic table group consisting of carbon (C), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), and flerovium (Fl). It lies within the p-block.

In modern International Union of Pure and Applied Ch ...

. This is unusual; ionization energies generally fall going down a group, as an element's outer electrons become more distant from the

nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

, and more

shielded by smaller orbitals. The sum of the first four ionization energies of lead exceeds that of tin, contrary to what

periodic trends

In chemistry, periodic trends are specific patterns present in the periodic table that illustrate different aspects of certain Chemical element, elements when grouped by period (periodic table), period and/or Group (periodic table), group. They w ...

would predict. This is explained by

relativistic effects, which become significant in heavier atoms, which contract s and p orbitals such that lead's 6s electrons have larger binding energies than its 5s electrons. A consequence is the so-called

inert pair effect

The inert-pair effect is the tendency of the two electrons in the outermost atomic ''s''-orbital to remain unshared in compounds of post-transition metals. The term ''inert-pair effect'' is often used in relation to the increasing stability of o ...

: the 6s electrons of lead become reluctant to participate in bonding, stabilising the +2

oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical Electrical charge, charge of an atom if all of its Chemical bond, bonds to other atoms are fully Ionic bond, ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons ...

and making the distance between nearest atoms in

crystalline

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

lead unusually long.

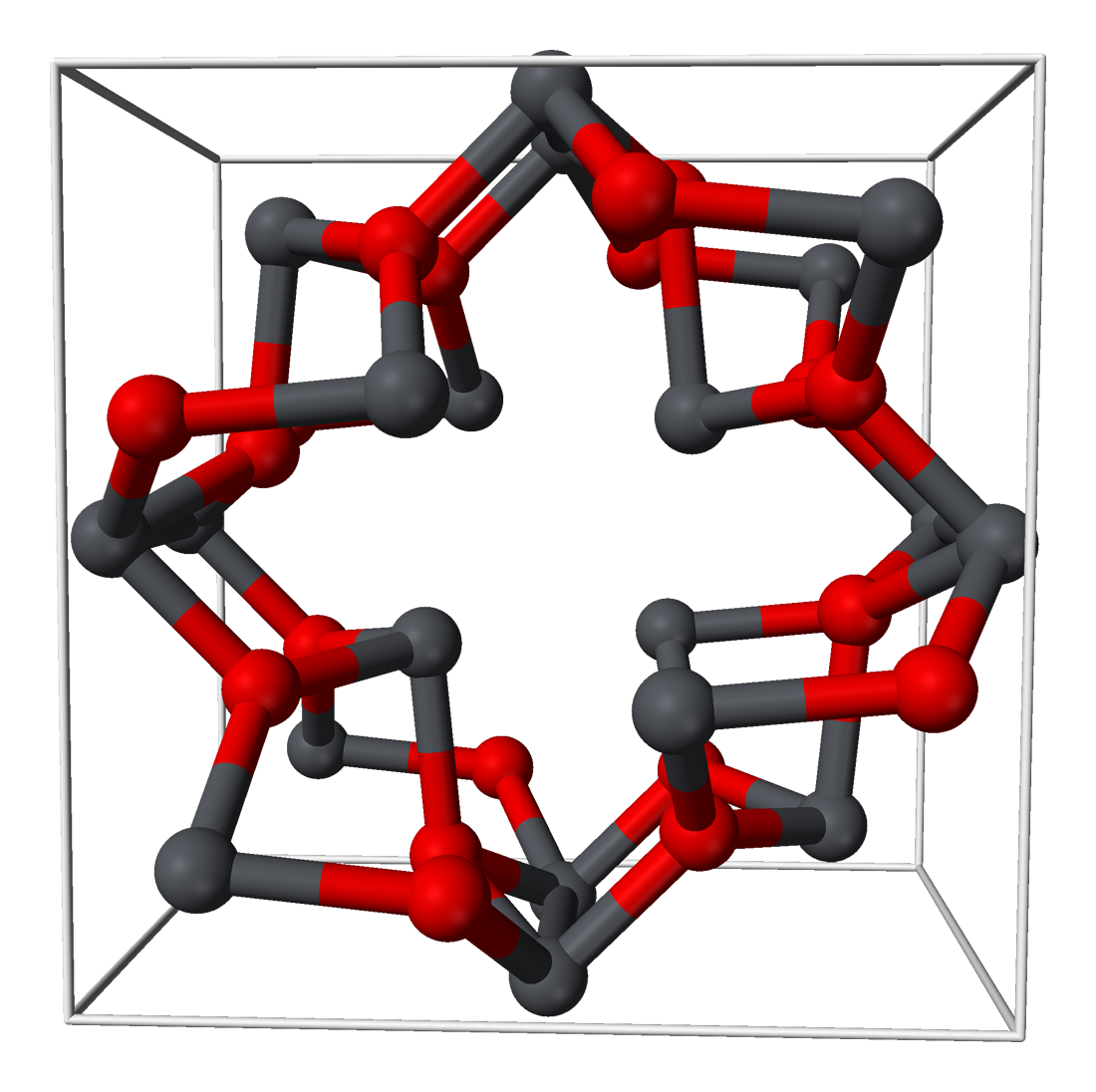

Lead's lighter carbon group

congeners form stable or metastable

allotropes

Allotropy or allotropism () is the property of some chemical elements to exist in two or more different forms, in the same physical state, known as allotropes of the elements. Allotropes are different structural modifications of an element: th ...

with the tetrahedrally coordinated and

covalently bonded

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

diamond cubic

In crystallography, the diamond cubic crystal structure is a repeating pattern of 8 atoms that certain materials may adopt as they solidify. While the first known example was diamond, other elements in group 14 also adopt this structure, in ...

structure. The energy levels of their outer

s- and

p-orbitals are close enough to allow mixing into four

hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two diff ...

sp

3 orbitals. In lead, the inert pair effect increases the separation between its s- and p-orbitals, and the gap cannot be overcome by the energy that would be released by extra bonds following hybridization. Rather than having a diamond cubic structure, lead forms

metallic bonds in which only the p-electrons are delocalized and shared between the Pb

2+ ions. Lead consequently has a

face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

structure like the similarly sized

divalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an atom is a measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules. Valence is generally understood to be the number of chemica ...

metals

calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

and

strontium

Strontium is a chemical element; it has symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, it is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is exposed to ...

.

Bulk

Pure lead has a bright, shiny gray appearance with a hint of blue. It tarnishes on contact with moist air and takes on a dull appearance, the hue of which depends on the prevailing conditions. Characteristic properties of lead include high

density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''Žü'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

, malleability, ductility, and high resistance to

corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

due to

passivation.

Lead's close-packed face-centered cubic structure and high atomic weight result in a density of 11.34 g/cm

3, which is greater than that of common metals such as

iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

(7.87 g/cm

3),

copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

(8.93 g/cm

3), and

zinc

Zinc is a chemical element; it has symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic tabl ...

(7.14 g/cm

3). This density is the origin of the idiom ''to go over like a lead balloon''. Some rarer metals are denser:

tungsten

Tungsten (also called wolfram) is a chemical element; it has symbol W and atomic number 74. It is a metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively in compounds with other elements. It was identified as a distinct element in 1781 and first ...

and

gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

are both at 19.3 g/cm

3, and

osmium

Osmium () is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Os and atomic number 76. It is a hard, brittle, bluish-white transition metal in the platinum group that is found as a Abundance of elements in Earth's crust, trace element in a ...

ŌĆöthe densest metal knownŌĆöhas a density of 22.59 g/cm

3, almost twice that of lead.

Lead is a very soft metal with a

Mohs hardness

The Mohs scale ( ) of mineral hardness is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fair ...

of 1.5; it can be scratched with a fingernail. It is quite malleable and somewhat ductile. The

bulk modulus

The bulk modulus (K or B or k) of a substance is a measure of the resistance of a substance to bulk compression. It is defined as the ratio of the infinitesimal pressure increase to the resulting ''relative'' decrease of the volume.

Other mo ...

of leadŌĆöa measure of its ease of compressibilityŌĆöis 45.8

GPa

Grading in education is the application of standardized measurements to evaluate different levels of student achievement in a course. Grades can be expressed as letters (usually A to F), as a range (for example, 1 to 6), percentages, or as num ...

. In comparison, that of

aluminium

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

is 75.2 GPa; copper 137.8 GPa; and

mild steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

160ŌĆō169 GPa. Lead's

tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (also called UTS, tensile strength, TS, ultimate strength or F_\text in notation) is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials, the ultimate ...

, at 12ŌĆō17 MPa, is low (that of aluminium is 6 times higher, copper 10 times, and mild steel 15 times higher); it can be strengthened by adding small amounts of copper or

antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

.

The melting point of leadŌĆöat 327.5 ┬░C (621.5 ┬░F)ŌĆöis very low compared to most metals. Its

boiling point

The boiling point of a substance is the temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the pressure surrounding the liquid and the liquid changes into a vapor.

The boiling point of a liquid varies depending upon the surrounding envi ...

of 1749 ┬░C (3180 ┬░F) is the lowest among the carbon-group elements. The

electrical resistivity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by ...

of lead at 20 ┬░C is 192

nanoohm-meters, almost an

order of magnitude

In a ratio scale based on powers of ten, the order of magnitude is a measure of the nearness of two figures. Two numbers are "within an order of magnitude" of each other if their ratio is between 1/10 and 10. In other words, the two numbers are ...

higher than those of other industrial metals (copper at ; gold ; and aluminium at ). Lead is a

superconductor at temperatures lower than 7.19

K; this is the highest

critical temperature

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

*Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing in ...

of all

type-I superconductor

The interior of a bulk superconductor cannot be penetrated by a weak magnetic field, a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect. When the applied magnetic field becomes too large, superconductivity breaks down. Superconductors can be divided into ...

s and the third highest of the elemental superconductors.

Isotopes

Natural lead consists of four stable

isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

s with mass numbers of 204, 206, 207, and 208, and traces of six short-lived radioisotopes with mass numbers 209ŌĆō214 inclusive. The high number of isotopes is consistent with lead's

atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

being even. Lead has a

magic number of protons (82), for which the

nuclear shell model

In nuclear physics, atomic physics, and nuclear chemistry, the nuclear shell model utilizes the Pauli exclusion principle to model the structure of atomic nuclei in terms of energy levels. The first shell model was proposed by Dmitri Ivanenk ...

accurately predicts an especially stable nucleus. Lead-208 has 126 neutrons, another magic number, which may explain why lead-208 is extraordinarily stable.

With its high atomic number, lead is the heaviest element whose natural isotopes are regarded as stable; lead-208 is the heaviest stable nucleus. (This distinction formerly fell to

bismuth

Bismuth is a chemical element; it has symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs nat ...

, with an atomic number of 83, until its only

primordial isotope

In geochemistry, geophysics and nuclear physics, primordial nuclides, also known as primordial isotopes, are nuclides found on Earth that have existed in their current form since before Earth was formed. Primordial nuclides were present in the ...

, bismuth-209, was found in 2003 to decay very slowly.) The four stable isotopes of lead could theoretically undergo

alpha decay

Alpha decay or ╬▒-decay is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits an alpha particle (helium nucleus). The parent nucleus transforms or "decays" into a daughter product, with a mass number that is reduced by four and an a ...

to isotopes of

mercury with a release of energy, but this has not been observed for any of them; their predicted half-lives range from 10

35 to 10

189 years (at least 10

25 times the current age of the universe).

Three of the stable isotopes are found in three of the four major

decay chain

In nuclear science a decay chain refers to the predictable series of radioactive disintegrations undergone by the nuclei of certain unstable chemical elements.

Radioactive isotopes do not usually decay directly to stable isotopes, but rather ...

s: lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208 are the final decay products of

uranium-238

Uranium-238 ( or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it i ...

,

uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

, and

thorium-232

Thorium-232 () is the main naturally occurring isotope of thorium, with a relative abundance of 99.98%. It has a half life of 14.05 billion years, which makes it the longest-lived isotope of thorium. It decays by alpha decay to radium-228; its de ...

, respectively. These decay chains are called the

uranium chain, the

actinium chain, and the

thorium chain

In nuclear science a decay chain refers to the predictable series of radioactive disintegrations undergone by the nuclei of certain unstable chemical elements.

Radioactive isotopes do not usually decay directly to stable isotopes, but rather ...

. Their isotopic concentrations in a natural rock sample depends greatly on the presence of these three parent uranium and thorium isotopes. For example, the relative abundance of lead-208 can range from 52% in normal samples to 90% in thorium ores; for this reason, the standard atomic weight of lead is given to only one decimal place. As time passes, the ratio of lead-206 and lead-207 to lead-204 increases, since the former two are supplemented by radioactive decay of heavier elements while the latter is not; this allows for

leadŌĆōlead dating

LeadŌĆōlead dating is a method for dating geological samples, normally based on 'whole-rock' samples of material such as granite. For most dating requirements it has been superseded by uraniumŌĆōlead dating (UŌĆōPb dating), but in certain special ...

. As uranium decays into lead, their relative amounts change; this is the basis for

uraniumŌĆōlead dating

UraniumŌĆōlead dating, abbreviated UŌĆōPb dating, is one of the oldest and most refined of the radiometric dating schemes. It can be used to date rocks that formed and crystallised from about 1 million years to over 4.5 billion years ago with routi ...

. Lead-207 exhibits

nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are disturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a ...

, a property that has been used to study its compounds in solution and solid state, including in the human body.

Apart from the stable isotopes, which make up almost all lead that exists naturally, there are

trace quantities of a few radioactive isotopes. One of them is lead-210; although it has a half-life of only 22.2 years, small quantities occur in nature because lead-210 is produced by a long decay series that starts with uranium-238 (that has been present for billions of years on Earth). Lead-211, ŌłÆ212, and ŌłÆ214 are present in the decay chains of uranium-235, thorium-232, and uranium-238, respectively, so traces of all three of these lead isotopes are found naturally. Minute traces of lead-209 arise from the very rare

cluster decay

Cluster decay, also named heavy particle radioactivity, heavy ion radioactivity or heavy cluster decay," is a rare type of nuclear decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a small "cluster" of neutrons and protons, more than in an alpha particle, ...

of radium-223, one of the

daughter products of natural uranium-235, the rare beta-minus-neutron decay of thallium-210 (a decay product of uranium-238), and the decay chain of neptunium-237, traces of which are produced by

neutron capture

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons, wh ...

in uranium ores. Lead-213 also occurs in the decay chain of neptunium-237. Lead-210 is particularly useful for helping to identify the ages of samples by measuring its ratio to lead-206 (both isotopes are present in a single decay chain).

In total, 43 lead isotopes have been synthesized, with mass numbers 178ŌĆō220. Lead-205 is the most stable radioisotope, with a half-life of around 1.70 years. The second-most stable is lead-202, which has a half-life of about 52,500 years, longer than any of the natural trace radioisotopes.

Chemistry

Bulk lead exposed to moist air forms a protective layer of varying composition.

Lead(II) carbonate is a common constituent; the

sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

or

chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

may also be present in urban or maritime settings. This layer makes bulk lead effectively chemically inert in the air. Finely powdered lead, as with many metals, is

pyrophoric

A substance is pyrophoric (from , , 'fire-bearing') if it ignites spontaneously in air at or below (for gases) or within 5 minutes after coming into contact with air (for liquids and solids). Examples are organolithium compounds and triethylb ...

, and burns with a bluish-white flame.

Fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

reacts with lead at room temperature, forming

lead(II) fluoride

Lead(II) fluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula Pb F2. It is a white solid. The compound is polymorphic, at ambient temperatures it exists in orthorhombic (PbCl2 type) form, while at high temperatures it is cubic ( Fluorite type). ...

. The reaction with

chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

is similar but requires heating, as the resulting chloride layer diminishes the reactivity of the elements. Molten lead reacts with the

chalcogen

The chalcogens (ore forming) ( ) are the chemical elements in group 16 of the periodic table. This group is also known as the oxygen family. Group 16 consists of the elements oxygen (O), sulfur (S), selenium (Se), tellurium (Te), and the rad ...

s to give lead(II) chalcogenides.

Lead metal resists

sulfuric

Sulfur (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form ...

and

phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, ...

but not

hydrochloric or

nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

; the outcome depends on insolubility and subsequent passivation of the product salt. Organic acids, such as

acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main compone ...

, dissolve lead in the presence of oxygen. Concentrated

alkali

In chemistry, an alkali (; from the Arabic word , ) is a basic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The a ...

s dissolve lead and form

plumbite In chemistry, plumbite is the oxyanion or hydrated forms, or any salt containing this anion. In these salts, lead is in the oxidation state +2. It is the traditional term for the IUPAC name plumbate(II).

For example, lead(II) oxide (PbO) dissolves ...

s.

Inorganic compounds

Lead shows two main oxidation states: +4 and +2. The

tetravalent state is common for the carbon group. The divalent state is rare for

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalentŌĆömeaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

and

silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

, minor for germanium, important (but not prevailing) for tin, and is the more important of the two oxidation states for lead. This is attributable to

relativistic effects, specifically the

inert pair effect

The inert-pair effect is the tendency of the two electrons in the outermost atomic ''s''-orbital to remain unshared in compounds of post-transition metals. The term ''inert-pair effect'' is often used in relation to the increasing stability of o ...

, which manifests itself when there is a large difference in

electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbolized as , is the tendency for an atom of a given chemical element to attract shared electrons (or electron density) when forming a chemical bond. An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the ...

between lead and

oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound containing at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion (anion bearing a net charge of ŌłÆ2) of oxygen, an O2ŌłÆ ion with oxygen in the oxidation st ...

,

halide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a fl ...

, or

nitride

In chemistry, a nitride is a chemical compound of nitrogen. Nitrides can be inorganic or organic, ionic or covalent. The nitride anion, N3ŌłÆ, is very elusive but compounds of nitride are numerous, although rarely naturally occurring. Some nitr ...

anions, leading to a significant partial positive charge on lead. The result is a stronger contraction of the lead 6s orbital than is the case for the 6p orbital, making it rather inert in ionic compounds. The inert pair effect is less applicable to compounds in which lead forms covalent bonds with elements of similar electronegativity, such as carbon in organolead compounds. In these, the 6s and 6p orbitals remain similarly sized and sp

3 hybridization is still energetically favorable. Lead, like carbon, is predominantly tetravalent in such compounds.

There is a relatively large difference in the electronegativity of lead(II) at 1.87 and lead(IV) at 2.33. This difference marks the reversal in the trend of increasing stability of the +4 oxidation state going down the carbon group; tin, by comparison, has values of 1.80 in the +2 oxidation state and 1.96 in the +4 state.

Lead(II)

Lead(II) compounds are characteristic of the inorganic chemistry of lead. Even strong

oxidizing agent

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ''electron donor''). In ot ...

s like fluorine and chlorine react with lead to give only

PbF2 and

PbCl2. Lead(II) ions are usually colorless in solution, and partially hydrolyze to form Pb(OH)

+ and finally

b4(OH)4sup>4+ (in which the

hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

ions act as

bridging ligand

In coordination chemistry, a bridging ligand is a ligand that connects two or more atoms, usually metal ions. The ligand may be atomic or polyatomic. Virtually all complex organic compounds can serve as bridging ligands, so the term is usually r ...

s), but are not

reducing agent

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are common reducing agents include hydrogen, carbon ...

s as tin(II) ions are.

Techniques for identifying the presence of the Pb

2+ ion in water generally rely on the precipitation of lead(II) chloride using dilute hydrochloric acid. As the chloride salt is sparingly soluble in water, in very dilute solutions the precipitation of

lead(II) sulfide

Lead(II) sulfide (also spelled '' sulphide'') is an inorganic compound with the formula Pb S. Galena is the principal ore and the most important compound of lead. It is a semiconducting material with niche uses.

Formation, basic properties, rel ...

is instead achieved by bubbling

hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

through the solution.

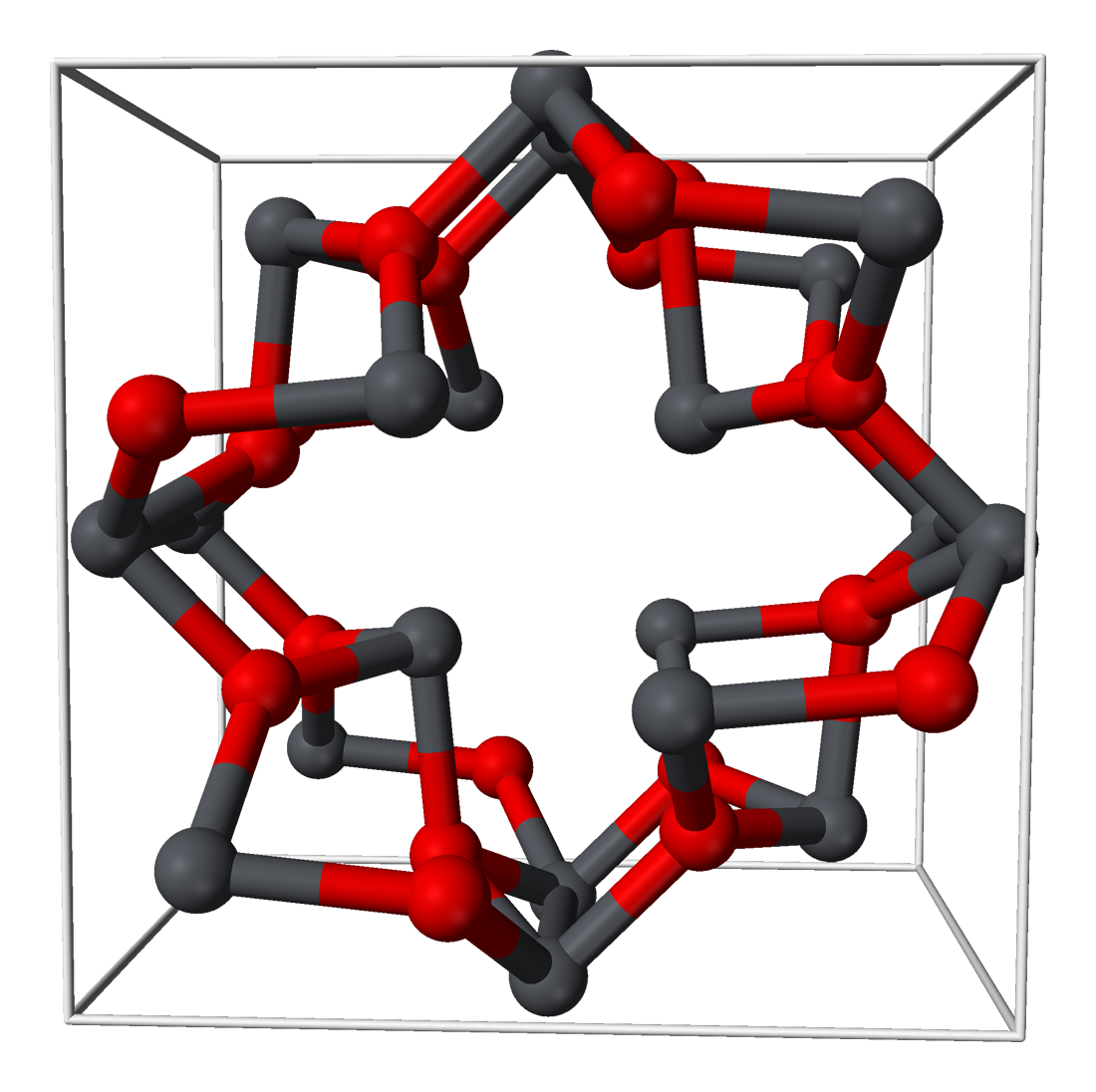

Lead monoxide exists in two

polymorphs,

litharge

Litharge (from Greek , 'stone' + 'silver' ) is one of the natural mineral forms of lead(II) oxide, PbO. Litharge is a secondary mineral which forms from the oxidation of galena ores. It forms as coatings and encrustations with internal tetr ...

╬▒-PbO (red) and

massicot

Massicot is lead (II) oxide mineral with an orthorhombic lattice structure.

Lead(II) oxide (formula: PbO) can occur in one of two lattice formats, orthorhombic and tetragonal. The red tetragonal form is called litharge. PbO can be changed from m ...

╬▓-PbO (yellow), the latter being stable only above around 488 ┬░C. Litharge is the most commonly used inorganic compound of lead. There is no lead(II) hydroxide; increasing the pH of solutions of lead(II) salts leads to hydrolysis and condensation. Lead commonly reacts with heavier chalcogens.

Lead sulfide Lead sulfide refers to two compounds containing lead and sulfur:

*Lead(II) sulfide

Lead(II) sulfide (also spelled '' sulphide'') is an inorganic compound with the formula Pb S. Galena is the principal ore and the most important compound of lead ...

is a

semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities (" doping") to its crystal structure. When two regions with different doping level ...

, a

photoconductor, and an extremely sensitive

infrared radiation detector. The other two chalcogenides,

lead selenide

Lead selenide (PbSe), or lead(II) selenide, a selenide of lead, is a semiconductor material. It forms cubic crystals of the NaCl structure; it has a direct bandgap of 0.27 eV at room temperature. (Note that incorrectly identifies PbSe and ...

and

lead telluride

Lead telluride is a compound of lead (element), lead and tellurium (PbTe). It crystallizes in the NaCl crystal structure with Pb atoms occupying the cation and Te forming the anionic lattice. It is a narrow gap semiconductor with a band gap of 0.3 ...

, are likewise photoconducting. They are unusual in that their color becomes lighter going down the group.

Lead dihalides are well-characterized; this includes the diastatide and mixed halides, such as PbFCl. The relative insolubility of the latter forms a useful basis for the

gravimetric determination of fluorine. The difluoride was the first solid

ionically conducting compound to be discovered (in 1834, by

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 ŌĆō 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

). The other dihalides decompose on exposure to ultraviolet or visible light, especially

the diiodide. Many lead(II)

pseudohalides are known, such as the cyanide, cyanate, and

thiocyanate

Thiocyanates are salts containing the thiocyanate anion (also known as rhodanide or rhodanate). is the conjugate base of thiocyanic acid. Common salts include the colourless salts potassium thiocyanate and sodium thiocyanate. Mercury(II) t ...

. Lead(II) forms an extensive variety of halide

coordination complex

A coordination complex is a chemical compound consisting of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of chemical bond, bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ' ...

es, such as

bCl4sup>2ŌłÆ,

bCl6sup>4ŌłÆ, and the

b2Cl9sub>''n''

5''n''ŌłÆ chain anion.

Lead(II) sulfate

Lead(II) sulfate (PbSO4) is a white solid, which appears white in microcrystalline form. It is also known as ''fast white'', ''milk white'', ''sulfuric acid lead salt'' or ''anglesite''.

It is often seen in the plates/electrodes of car batteries ...

is insoluble in water, like the sulfates of other heavy divalent

cations

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

.

Lead(II) nitrate

Lead(II) nitrate is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Pb( NO3)2. It commonly occurs as a colourless crystal or white powder and, unlike most other lead(II) salts, is soluble in water.

Known since the Middle Ages by the name plumbum ...

and

lead(II) acetate

Lead(II) acetate is a white crystalline chemical compound with a slightly sweet taste. Its chemical formula is usually expressed as or , where Ac represents the acetyl group. Like many other lead compounds, it causes lead poisoning. Lead aceta ...

are very soluble, and this is exploited in the synthesis of other lead compounds.

Lead(IV)

Few inorganic lead(IV) compounds are known. They are only formed in highly oxidizing solutions and do not normally exist under standard conditions. Lead(II) oxide gives a mixed oxide on further oxidation, Pb

3O

4. It is described as

lead(II,IV) oxide, or structurally 2PbO┬ĘPbO

2, and is the best-known mixed valence lead compound.

Lead dioxide

Lead(IV) oxide, commonly known as lead dioxide, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is an oxide where lead is in an oxidation state of +4. It is a dark-brown solid which is insoluble in water. It exists in two crystalline forms ...

is a strong oxidizing agent, capable of oxidizing hydrochloric acid to chlorine gas. This is because the expected PbCl

4 that would be produced is unstable and spontaneously decomposes to PbCl

2 and Cl

2. Analogously to

lead monoxide, lead dioxide is capable of forming

plumbate

In chemistry, a plumbate often refers to compounds that can be viewed as derivatives of the hypothetical anion.

Examples Halides

Salts of , , , etc. are labeled as iodoplumbates. Lead perovskite semiconductors are often described as plumbates.

...

anions.

Lead disulfide and lead diselenide are only stable at high pressures.

Lead tetrafluoride, a yellow crystalline powder, is stable, but less so than the

difluoride.

Lead tetrachloride (a yellow oil) decomposes at room temperature, lead tetrabromide is less stable still, and the existence of lead tetraiodide is questionable.

Other oxidation states

Some lead compounds exist in formal oxidation states other than +4 or +2. Lead(III) may be obtained, as an intermediate between lead(II) and lead(IV), in larger organolead complexes; this oxidation state is not stable, as both the lead(III) ion and the larger complexes containing it are

radicals

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

. The same applies for lead(I), which can be found in such radical species.

Numerous mixed lead(II,IV) oxides are known. When PbO

2 is heated in air, it becomes Pb

12O

19 at 293 ┬░C, Pb

12O

17 at 351 ┬░C, Pb

3O

4 at 374 ┬░C, and finally PbO at 605 ┬░C. A further

sesquioxide

A sesquioxide is an oxide of an element (or radical), where the ratio between the number of atoms of that element and the number of atoms of oxygen is 2:3. For example, aluminium oxide and phosphorus(III) oxide are sesquioxides.

Many sesquioxid ...

, Pb

2O

3, can be obtained at high pressure, along with several non-stoichiometric phases. Many of them show defective

fluorite

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scal ...

structures in which some oxygen atoms are replaced by vacancies: PbO can be considered as having such a structure, with every alternate layer of oxygen atoms absent.

Negative oxidation states can occur as

Zintl phases, as either free lead anions, as in Ba

2Pb, with lead formally being lead(ŌłÆIV), or in oxygen-sensitive ring-shaped or polyhedral cluster ions such as the

trigonal bipyramidal Pb

52ŌłÆ ion, where two lead atoms are lead(ŌłÆI) and three are lead(0). In such anions, each atom is at a polyhedral vertex and contributes two electrons to each covalent bond along an edge from their sp

3 hybrid orbitals, the other two being an external

lone pair

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bondIUPAC ''Gold Book'' definition''lone (electron) pair''/ref> and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone ...

. They may be made in

liquid ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pungent smell. It is widely used in fertilizers, ...

via the reduction of lead by

sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

.

Organolead

Lead can form

multiply-bonded chains, a property it shares with its lighter

homologs

Homologous chromosomes or homologs are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during meiosis. Homologs have the same genes in the same loci, where they provide points along each chromosome th ...

in the carbon group. Its capacity to do so is much less because the PbŌĆōPb

bond energy

In chemistry, bond energy (''BE'') is one measure of the strength of a chemical bond. It is sometimes called the mean bond, bond enthalpy, average bond enthalpy, or bond strength. IUPAC defines bond energy as the average value of the gas-phase b ...

is over three and a half times lower than that of the

CŌĆōC bond. With itself, lead can build metalŌĆōmetal bonds of an order up to three. With carbon, lead forms organolead compounds similar to, but generally less stable than, typical organic compounds (due to the PbŌĆōC bond being rather weak). This makes the

organometallic chemistry

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

of lead far less wide-ranging than that of tin. Lead predominantly forms organolead(IV) compounds, even when starting with inorganic lead(II) reactants; very few organolead(II) compounds are known. The most well-characterized exceptions are Pb

H(SiMe3)2sub>2 and

plumbocene.

The lead analog of the simplest

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbonŌĆōhydrogen or carbonŌĆōcarbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

,

methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

, is

plumbane

Plumbane is an inorganic chemical compound with the chemical formula PbH. It is a colorless gas. It is a metal hydride and group 14 hydride composed of lead and hydrogen. Plumbane is not well characterized or well known, and it is thermodynamicall ...

. Plumbane may be obtained in a reaction between metallic lead and atomic hydrogen. Two simple derivatives,

tetramethyllead

Tetramethyllead, also called tetra methyllead and lead tetramethyl, is a chemical compound used as an antiknock additive for gasoline. It is a methyl radical synthon. Its use in gasoline is being phased out for environmental considerations.

Th ...

and

tetraethyllead

Tetraethyllead (commonly styled tetraethyl lead), abbreviated TEL, is an organolead compound with the formula lead, Pb(ethyl group, C2H5)4. It was widely used as a fuel additive for much of the 20th century, first being mixed with gasoline begi ...

, are the best-known

organolead compounds. These compounds are relatively stable: tetraethyllead only starts to decompose if heated or if exposed to sunlight or ultraviolet light. With sodium metal, lead readily forms an equimolar alloy that reacts with

alkyl halides

The haloalkanes (also known as halogenoalkanes or alkyl halides) are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents of hydrogen atom. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalka ...

to form

organometallic

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

compounds such as tetraethyllead. The oxidizing nature of many organolead compounds is usefully exploited:

lead tetraacetate is an important laboratory reagent for oxidation in organic synthesis. Tetraethyllead, once added to automotive gasoline, was produced in larger quantities than any other organometallic compound, and is still widely used in

fuel for small aircraft.

Other organolead compounds are less chemically stable. For many organic compounds, a lead analog does not exist.

Origin and occurrence

In space

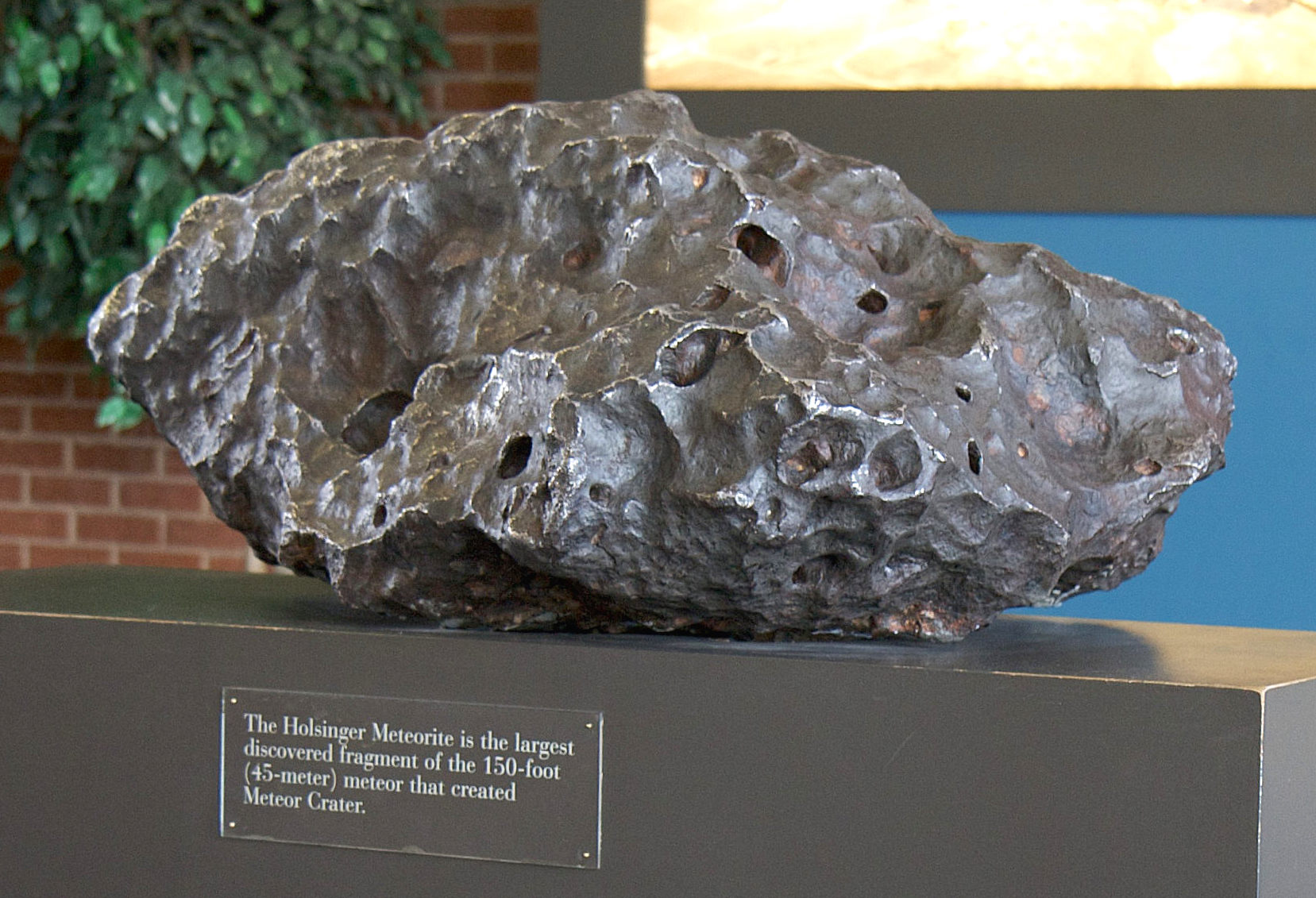

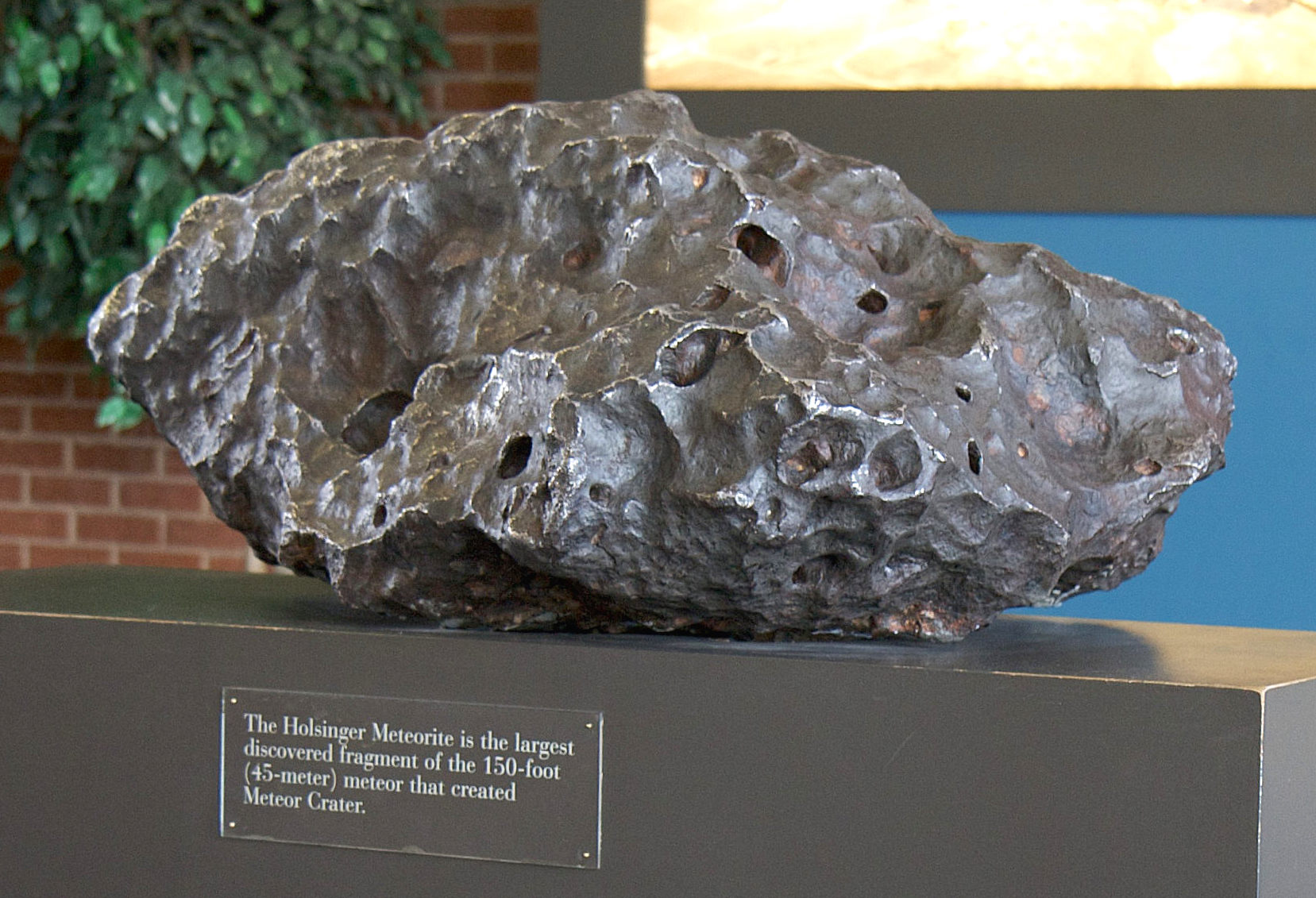

Lead's per-particle abundance in the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

is 0.121

ppb (parts per billion). This figure is two and a half times higher than that of

platinum

Platinum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a density, dense, malleable, ductility, ductile, highly unreactive, precious metal, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name origina ...

, eight times more than

mercury, and seventeen times more than

gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

. The amount of lead in the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

is slowly increasing as most heavier atoms (all of which are unstable) gradually decay to lead. The abundance of lead in the Solar System since its formation 4.5 billion years ago has increased by about 0.75%. The Solar System abundances table shows that lead, despite its relatively high atomic number, is more prevalent than most other elements with atomic numbers greater than 40.

Primordial leadŌĆöwhich comprises the isotopes lead-204, lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208ŌĆöwas mostly created as a result of repetitive neutron capture processes occurring in stars. The two main modes of capture are the

s- and

r-process

In nuclear astrophysics, the rapid neutron-capture process, also known as the ''r''-process, is a set of nuclear reactions that is responsible for nucleosynthesis, the creation of approximately half of the Atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei Heavy meta ...

es.

In the s-process (s is for "slow"), captures are separated by years or decades, allowing less stable nuclei to undergo

beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (╬▓-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

. A stable thallium-203 nucleus can capture a neutron and become thallium-204; this undergoes beta decay to give stable lead-204; on capturing another neutron, it becomes lead-205, which has a half-life of around 17 million years. Further captures result in lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208. On capturing another neutron, lead-208 becomes lead-209, which quickly decays into bismuth-209. On capturing another neutron, bismuth-209 becomes bismuth-210, and this beta decays to polonium-210, which alpha decays to lead-206. The cycle hence ends at lead-206, lead-207, lead-208, and bismuth-209.

In the r-process (r is for "rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. This occurs in environments with a high neutron density, such as a

supernova

A supernova (: supernovae or supernovas) is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. A supernova occurs during the last stellar evolution, evolutionary stages of a massive star, or when a white dwarf is triggered into runaway nuclear fusion ...

or the merger of two

neutron star

A neutron star is the gravitationally collapsed Stellar core, core of a massive supergiant star. It results from the supernova explosion of a stellar evolution#Massive star, massive starŌĆöcombined with gravitational collapseŌĆöthat compresses ...

s. The neutron flux involved may be on the order of 10

22 neutrons per square centimeter per second. The r-process does not form as much lead as the s-process. It tends to stop once neutron-rich nuclei reach 126 neutrons. At this point, the neutrons are arranged in complete shells in the atomic nucleus, and it becomes harder to energetically accommodate more of them. When the neutron flux subsides, these nuclei beta decay into stable isotopes of

osmium

Osmium () is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Os and atomic number 76. It is a hard, brittle, bluish-white transition metal in the platinum group that is found as a Abundance of elements in Earth's crust, trace element in a ...

,

iridium

Iridium is a chemical element; it has the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. This very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density ...

,

platinum

Platinum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a density, dense, malleable, ductility, ductile, highly unreactive, precious metal, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name origina ...

.

On Earth

Lead is classified as a

chalcophile under the

Goldschmidt classification, meaning it is generally found combined with sulfur. It rarely occurs in its

native

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

, metallic form. Many lead minerals are relatively light and, over the course of the Earth's history, have remained in the

crust instead of sinking deeper into the Earth's interior. This accounts for lead's relatively high

crustal abundance of 14 ppm; it is the 36th most

abundant element in the crust.

The main lead-bearing mineral is

galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crysta ...

(PbS), which is mostly found with zinc ores. Most other lead minerals are related to galena in some way;

boulangerite, Pb

5Sb

4S

11, is a mixed sulfide derived from galena;

anglesite

Anglesite is a lead sulfate mineral with the chemical formula PbSO4. It occurs as an oxidation product of primary lead sulfide ore, galena. Anglesite occurs as prismatic orthorhombic crystals and earthy masses, and is isomorphous with barite and ...

, PbSO

4, is a product of galena oxidation; and

cerussite

Cerussite (also known as lead carbonate or white lead ore) is a mineral consisting of lead carbonate with the chemical formula PbCO3, and is an important ore of lead. The name is from the Latin ''cerussa'', white lead. ''Cerussa nativa'' was ...

or white lead ore, PbCO

3, is a

decomposition

Decomposition is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is ess ...

product of galena.

Arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

,

tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

,

antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

,

silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

,

gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

,

copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

,

bismuth

Bismuth is a chemical element; it has symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs nat ...

are common impurities in lead minerals.

World lead resources exceed two billion tons. Significant deposits are located in Australia, China, Ireland, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Russia, United States. Global reservesŌĆöresources that are economically feasible to extractŌĆötotaled 88 million tons in 2016, of which

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

had 35 million, China 17 million, Russia 6.4 million.

Typical background concentrations of lead do not exceed 0.1 ╬╝g/m

3 in the atmosphere; 100 mg/kg in soil; 4 mg/kg in vegetation, 5 ╬╝g/L in fresh water and seawater.

Etymology

The modern English word ''lead'' is of Germanic origin; it comes from the

Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

and

Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

(with the

macron above the "e" signifying that the vowel sound of that letter is long). The Old English word is derived from the hypothetical reconstructed

Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages, Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from ...

('lead'). According to linguistic theory, this word bore descendants in multiple Germanic languages of exactly the same meaning.

There is no consensus on the origin of the Proto-Germanic . One hypothesis suggests it is derived from

Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

('lead'; capitalization of the vowel is equivalent to the macron). Another hypothesis suggests it is borrowed from

Proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly Linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed throu ...

('lead'). This word is related to the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, which gave the element its

chemical symbol

Chemical symbols are the abbreviations used in chemistry, mainly for chemical elements; but also for functional groups, chemical compounds, and other entities. Element symbols for chemical elements, also known as atomic symbols, normally consist ...

''Pb''. The word is thought to be the origin of Proto-Germanic (which also means 'lead'), from which stemmed the German .

The name of the chemical element is not related to the verb of the same spelling, which is derived from Proto-Germanic ('to lead').

History

Prehistory and early history

Metallic lead beads

dating back to 7000ŌĆō6500 BC have been found in

Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and may represent the first example of metal

smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron-making, iron, copper extraction, copper ...

. At that time, lead had few (if any) applications due to its softness and dull appearance. The major reason for the spread of lead production was its association with silver, which may be obtained by burning galena (a common lead mineral). The

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ians were the first to use lead minerals in cosmetics, an application that spread to

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12thŌĆō9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and beyond; the Egyptians had used lead for sinkers in

fishing nets

A fishing net or fish net is a net (device), net used for fishing. Fishing nets work by serving as an improvised fish trap, and some are indeed rigged as traps (e.g. #Fyke nets, fyke nets). They are usually wide open when deployed (e.g. by cast ...

,

glazes,

glasses

Glasses, also known as eyeglasses (American English), spectacles (Commonwealth English), or colloquially as specs, are vision eyewear with clear or tinted lenses mounted in a frame that holds them in front of a person's eyes, typically u ...

,

enamels,

ornaments

An ornament is something used for decoration.

Ornament may also refer to:

Decoration

*Ornament (art), any purely decorative element in architecture and the decorative arts

*Ornamental turning

*Biological ornament, a characteristic of animals tha ...

. Various civilizations of the

Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

used lead as a

writing material

A writing material, also called a writing medium, is a surface that can be written on with suitable instruments, or used for symbolic or representational drawings. Building materials on which writings or drawings are produced are not included. ...

, as

coin

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

s, and as a

construction material

This is a list of building materials.

Many types of building materials are used in the construction industry to create buildings and structures. These categories of materials and products are used by architects and construction project manager

...

. Lead was used by the ancient Chinese as a

stimulant

Stimulants (also known as central nervous system stimulants, or psychostimulants, or colloquially as uppers) are a class of drugs that increase alertness. They are used for various purposes, such as enhancing attention, motivation, cognition, ...

, as

currency

A currency is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins. A more general definition is that a currency is a ''system of money'' in common use within a specific envi ...

, as

contraceptive

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, and in

chopsticks

Chopsticks are shaped pairs of equal-length sticks that have been used as kitchen and eating utensils in most of East Asia for over three millennia. They are held in the dominant hand, secured by fingers, and wielded as extensions of the han ...

. The

Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE ...

and the

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

ns used it for making

amulets

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a pers ...

; and the eastern and southern Africans used lead in

wire drawing

Wire drawing is a metalworking process used to reduce the cross-section of a wire by pulling the wire through one or more dies. There are many applications for wire drawing, including electrical wiring, cables, tension-loaded structural compone ...

.

Classical era

Because silver was extensively used as a decorative material and an exchange medium, lead deposits came to be worked in Asia Minor from 3000 BC; later, lead deposits were developed in the

Aegean and

Laurion

Lavrio, Lavrion or Laurium (; (later ); from Middle Ages until 1908: ╬ĢŽü╬│╬▒ŽāŽä╬«Žü╬╣╬▒ ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica Region, Attica, Greece. It is part of Athens metropolitan area and the seat of the municipalit ...

. These three regions collectively dominated production of mined lead until . Beginning c. 2000 BC, the

Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns worked deposits in the

Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

; by 1600 BC, lead mining existed in

Cyprus