Karl Dönitz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

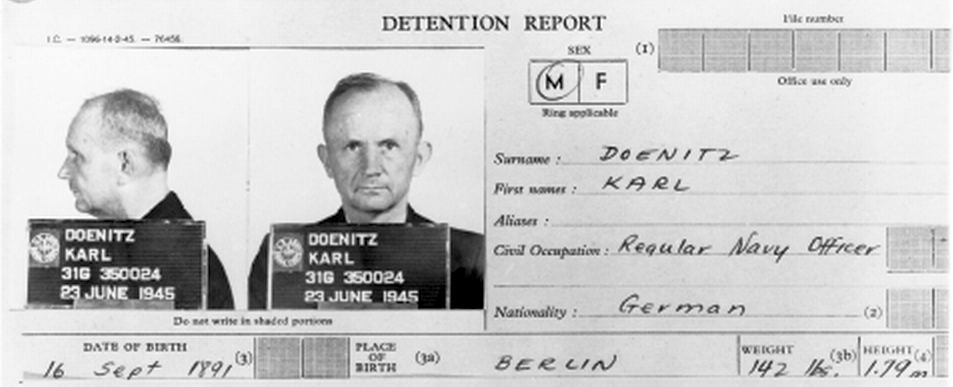

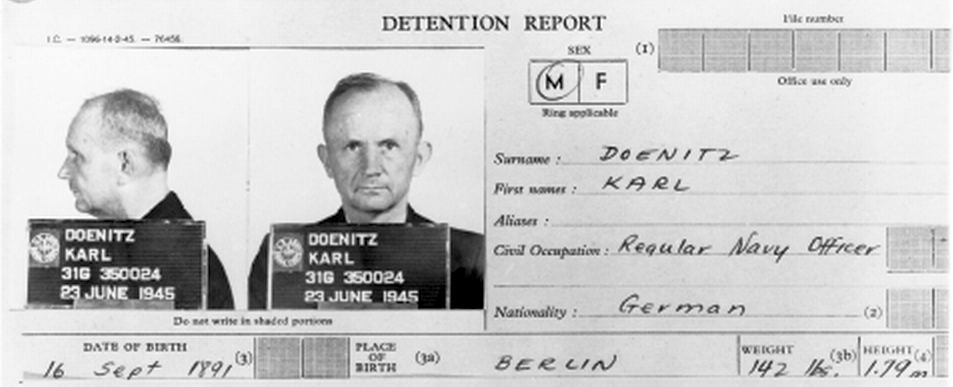

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a

Dönitz was born in Grünau, near

Dönitz was born in Grünau, near

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (, ''BdU''). For the first part of the war, despite disagreements with Raeder where best to deploy his men, Dönitz was given considerable operational freedom for his junior rank.

From September–December 1939 U-boats sank 221 ships for 755,237 gross tons, at the cost of nine U-boats. Only 47 merchant ships were sunk in the

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (, ''BdU''). For the first part of the war, despite disagreements with Raeder where best to deploy his men, Dönitz was given considerable operational freedom for his junior rank.

From September–December 1939 U-boats sank 221 ships for 755,237 gross tons, at the cost of nine U-boats. Only 47 merchant ships were sunk in the

Signals security aroused Dönitz's suspicions during the war. On 12 January 1942 German supply submarine ''U-459'' arrived 800 nautical miles west of

Signals security aroused Dönitz's suspicions during the war. On 12 January 1942 German supply submarine ''U-459'' arrived 800 nautical miles west of

New construction procedures, dispensing with prototypes and the abandonment of modifications reduced construction times from 460,000-man hours to 260–300,000 to meet Speer's quota. In the spring 1944, the

New construction procedures, dispensing with prototypes and the abandonment of modifications reduced construction times from 460,000-man hours to 260–300,000 to meet Speer's quota. In the spring 1944, the

That month, 21 boats fought a battle with two formations;

That month, 21 boats fought a battle with two formations;

In the final days of the war, after Hitler had taken refuge in the beneath the

In the final days of the war, after Hitler had taken refuge in the beneath the

On 4 May, Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, representing Dönitz, surrendered all German forces in the

On 4 May, Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, representing Dönitz, surrendered all German forces in the

Dönitz contributed to the spread of Nazism within the . He insisted that officers share his political views and, as head of the , formally joined the Nazi Party on 1 February 1944, as member 9,664,999. He was awarded the

Dönitz contributed to the spread of Nazism within the . He insisted that officers share his political views and, as head of the , formally joined the Nazi Party on 1 February 1944, as member 9,664,999. He was awarded the

Following the war, Dönitz was held as a prisoner of war by the Allies. He was indicted as a major war criminal at the

Following the war, Dönitz was held as a prisoner of war by the Allies. He was indicted as a major war criminal at the  Among the war-crimes charges, Dönitz was accused of waging unrestricted submarine warfare for issuing War Order No. 154 in 1939, and another similar order after the ''Laconia'' incident in 1942, not to rescue survivors from ships attacked by submarine. By issuing these two orders, he was found guilty of causing Germany to be in breach of the

Among the war-crimes charges, Dönitz was accused of waging unrestricted submarine warfare for issuing War Order No. 154 in 1939, and another similar order after the ''Laconia'' incident in 1942, not to rescue survivors from ships attacked by submarine. By issuing these two orders, he was found guilty of causing Germany to be in breach of the

Dönitz's second book, (''My Ever-Changing Life'') is less known, perhaps because it deals with the events of his life before 1934. This book was first published in 1968, and a new edition was released in 1998 with the revised title (''My Martial Life''). In 1973, he appeared in the

Dönitz's second book, (''My Ever-Changing Life'') is less known, perhaps because it deals with the events of his life before 1934. This book was first published in 1968, and a new edition was released in 1998 with the revised title (''My Martial Life''). In 1973, he appeared in the

Historical Enigma message

Grand Admiral Dönitz announcing his appointment as Hitler's successor. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Donitz, Karl 1891 births 1980 deaths 20th-century presidents of Germany Articles containing video clips Commanders of the Military Order of Savoy Crosses of Naval Merit Fascist rulers German people convicted of war crimes Grand admirals of the Kriegsmarine Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Heads of government who were later imprisoned Heads of state convicted of war crimes Imperial German Navy personnel of World War I Naval history of World War II Nazi Party officials People convicted by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People from the Province of Brandenburg Politicians from Berlin Presidents of Germany Recipients of the clasp to the Iron Cross, 1st class Recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 1st class Recipients of the Order of Michael the Brave, 1st class Reichsmarine personnel U-boat commanders (Imperial German Navy) Military personnel from Berlin People from Treptow-Köpenick

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government following Germany's unconditional surrender to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

days later. As Supreme Commander of the Navy beginning in 1943, he played a major role in the naval history of World War II

At the beginning of World War II, the Royal Navy was the strongest navy in the world, with the largest number of warships built and with naval bases across the globe. It had over 15 battleships and battlecruisers, 7 aircraft carriers, 66 cruisers ...

.

He began his career in the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. In 1918, he was commanding , and was taken prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

by British forces. While in a POW camp, he formulated what he later called ''Rudeltaktik'' ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack").

By the start of the Second World War, Dönitz was supreme commander of the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' U-boat arm ( (BdU)). In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of (grand admiral) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy. Dönitz was the main enemy of Allied naval forces in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

. From 1939 to 1943 the U-boats fought effectively but lost the initiative from May 1943. Dönitz ordered his submarines into battle until 1945 to relieve the pressure on other branches of the (armed forces). 648 U-boats were lost—429 with no survivors. Furthermore, of these, 215 were lost on their first patrol. Around 30,000 of the 40,000 men who served in U-boats perished.

On 30 April 1945, after the suicide of Adolf Hitler and in accordance with his last will and testament, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as head of state, with the title of President of Germany

The president of Germany, officially the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: link=no, Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland),The official title within Germany is ', with ' being added in international corres ...

and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations Staff of the (OKW), to sign the German instruments of surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

in Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

, France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May.

By his own admission, Dönitz was a dedicated Nazi and supporter of Hitler. Following the war, he was indicted as a major war criminal at the Nuremberg trials on three counts: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace

A crime of aggression or crime against peace is the planning, initiation, or execution of a large-scale and serious act of aggression using state military force. The definition and scope of the crime is controversial. The Rome Statute contains an ...

, war crimes, and crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

; planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor sanc ...

; and crimes against the laws of war. He was found not guilty of committing crimes against humanity, but guilty of committing crimes against peace and war crimes against the laws of war. He was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment; after his release, he lived in a village near Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

until his death in 1980, after a prolonged illness.

Early life and career

Dönitz was born in Grünau, near

Dönitz was born in Grünau, near Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, to Anna Beyer and Emil Dönitz, an engineer, in 1891. Karl had an older brother. In 1910, Dönitz enlisted in the ("Imperial Navy").

On 27 September 1913, Dönitz was commissioned as a (acting sub-lieutenant). When World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

began, he served on the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. In August 1914, the ''Breslau'' and the battlecruiser were sold to the Ottoman Navy; the ships were renamed the ''Midilli'' and the ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'', respectively. They began operating out of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, under Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the ''Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry o ...

, engaging Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

forces in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

. On 22 March 1916, Dönitz was promoted to . He requested a transfer to the submarine forces, which became effective on 1 October 1916. He attended the submariner's school at Flensburg-Mürwik and passed out on 3 January 1917. He served as watch officer on , and from February 1918 onward as commander of . On 2 July 1918, he became commander of , operating in the Mediterranean. On 4 October, after suffering technical difficulties, Dönitz was forced to surface and scuttled his boat. He was captured by the British and incarcerated in the Redmires camp near Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

. He remained a prisoner of war until 1919 and in 1920 he returned to Germany.

On 27 May 1916, Dönitz married a nurse named Ingeborg Weber (1893–1962), the daughter of German general Erich Weber (1860–1933). They had three children whom they raised as Protestant Christians: daughter Ursula (1917–1990) and sons Klaus (1920–1944) and Peter (1922–1943). Both of Dönitz's sons were killed during the Second World War. Peter was killed on 19 May 1943 when was sunk in the North Atlantic with all hands.

Hitler had issued a policy stating that if a senior officer such as Dönitz lost a son in battle and had other sons in the military, the latter could withdraw from combat and return to civilian life.

After Peter's death Klaus was forbidden to have any combat role and was allowed to leave the military to begin studying to become a naval doctor. He returned to sea and was killed on 13 May 1944; he had persuaded his friends to let him go on the E-boat

E-boat was the Western Allies' designation for the fast attack craft (German: ''Schnellboot'', or ''S-Boot'', meaning "fast boat") of the Kriegsmarine during World War II; ''E-boat'' could refer to a patrol craft from an armed motorboat to a lar ...

''S-141'' for a raid on Selsey

Selsey is a seaside town and civil parish, about eight miles (12 km) south of Chichester in West Sussex, England. Selsey lies at the southernmost point of the Manhood Peninsula, almost cut off from mainland Sussex by the sea. It is bounde ...

on his 24th birthday. The boat was sunk by the French destroyer ''La Combattante''.

Interwar period

He continued his naval career in the naval arm of theWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

's armed forces. On 10 January 1921, he became a (lieutenant) in the new German navy (). Dönitz commanded torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s, becoming a (lieutenant-commander) on 1 November 1928. On 1 September 1933, he became a (commander) and, in 1934, was put in command of the cruiser ''Emden'', the ship on which cadets and midshipmen took a year-long world cruise as training.

In 1935, the was renamed . Germany was prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

from possessing a submarine fleet. The Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the '' Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio whe ...

of 1935 allowed submarines and he was placed in command of the U-boat flotilla , which comprised three boats; ; and; . On 1 September 1935, he was promoted to (naval captain).

Dönitz opposed Raeder's views that surface ships should be given priority in the during the war, but in 1935 Dönitz doubted U-boat suitability in a naval trade war on account of their slow speed. This phenomenal contrast with Dönitz's wartime policy is explained in the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement. The accord was viewed by the navy with optimism, Dönitz included. He remarked, "Britain, in the circumstances, could not possibly be included in the number of potential enemies." The statement, made after June 1935, was uttered at a time when the naval staff were sure France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

were likely to be Germany's only enemies. Dönitz's statement was partially correct. Britain was not foreseen as an immediate enemy, but the navy still held onto a cadre of imperial officers, which along with its Nazi-instigated intake, understood war would be certain in the distant future, perhaps not until the mid-1940s.

Dönitz came to recognise the need for more of these vessels. Only 26 were in commission or under construction that summer. In the time before his command of submarines, he perfected the group tactics that first appealed to him in 1917. At this time Dönitz first expressed his procurement policies. His preference for the submarine fleet was in the production of large numbers of small craft. In contrast to other warships, the fighting power of the U-boat, in his opinion, was not dependent on its size as the torpedo, not the gun, was the machine's main weapon. Dönitz had a tendency to be critical of larger submarines and listed a number of disadvantages in their production, operation and tactical use. Dönitz recommended the Type VII submarine

Type VII U-boats were the most common type of German World War II U-boat. 703 boats were built by the end of the war. The lone surviving example, , is on display at the Laboe Naval Memorial located in Laboe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

Con ...

as the ideal submarine. The boat was reliable and had a range of 6,200 miles. Modifications lengthened this to 8,700 miles.

Dönitz revived Hermann Bauer

Hermann Bauer (22 July 1875 – 11 February 1958) was a Germans, German naval officer who served as commander of the U-boat forces of the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' during World War I. In addition to his World War I career, Bauer is well known as the ...

's idea of grouping several submarines together into a ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack") to overwhelm a merchant convoy's escorts. Implementation of wolfpacks had been difficult in World War I owing to the limitations of available radios. In the interwar years, Germany had developed ultra high frequency transmitters, (ukw) while the Enigma cipher machine was believed to have made communications secure. A 1922 paper written by Wessner of the (Defence Ministry) pointed to the success of surface attacks at night and the need to coordinate operations with multiple boats to defeat the escorts. Dönitz knew of the paper and improved the ideas suggested by Wessner. This tactic had the added advantage that a submarine on the surface was undetectable by Asdic. Dönitz claimed after the war he would not allow his service to be intimidated by British disclosures about Asdic

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects on ...

and the course of the war had proven him right. In reality, Dönitz harboured fears stretching back to 1937 that the new technology would render the U-boat impotent. Dönitz published his ideas on night attacks in January 1939 in a booklet called which apparently went unnoticed by the British. The Royal Navy's overconfidence in Asdic encouraged the Admiralty to suppose it could deal with submarines whatever strategy they adopted — in this they were proven wrong; submarines were difficult to locate and destroy under operational conditions.

In 1939 he expressed his belief that he could win the war with 300 vessels. The Nazi leadership's rearmament priorities were fundamentally geared to land and aerial warfare. From 1933 to 1936, the navy was granted only 13 percent of total armament expenditure. The production of U-boats, despite the existing Z Plan, remained low. In 1935 shipyards produced 14 submarines, 21 in 1936, 1 in 1937. In 1938 nine were commissioned and in 1939 18 U-boats were built. Dönitz's vision may have been misguided. The British had planned for contingency construction programmes for the summer, 1939. At least 78 small escorts and a crash construction programme of " Whale catchers" had been invoked. The British, according to one historian, had taken all the sensible steps necessary to deal with the U-boat menace as it existed in 1939 and were well placed to deal with large numbers of submarines, prior to events in 1940.

World War II

On 1 September 1939,Germany invaded Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

. Britain and France soon declared war on Germany, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

began. On Sunday 3 September, Dönitz chaired a conference at Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

. At 11:15 am the British Admiralty sent out a signal "Total Germany". B-Dienst intercepted the message and it was promptly reported to Dönitz. Dönitz paced around the room and his staff purportedly heard him repeatedly say, "My God! So it's war with England again!"

Dönitz abandoned the conference to return within the hour a far more composed man. He announced to his officers, "we know our enemy. We have today the weapon and a leadership that can face up to this enemy. The war will last a long time; but if each does his duty we will win." Dönitz had only 57 boats; of those, 27 were capable of reaching the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

from their German bases. A small building program was already under way but the number of U-boats did not rise noticeably until the autumn of 1941.

Dönitz's first major action was the cover up of the sinking of the British passenger liner ''Athenia'' later the same day. Acutely sensitive to international opinion and relations with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the death of more than a hundred civilians was damaging. Dönitz suppressed the truth that the ship was sunk by a German submarine. He accepted the commander's explanation that he genuinely believed the ship was armed. Dönitz ordered the engagement to be struck from the submarine's logbook. Dönitz did not admit the cover up until 1946.

Hitler's original orders to wage war only in accordance with the Prize Regulations, were not issued in any altruistic spirit but in the belief hostilities with the Western Allies would be brief. On 23 September 1939, Hitler, on the recommendation of Admiral Raeder, approved that all merchant ships making use of their wireless on being stopped by U-boats should be sunk or captured. This German order marked a considerable step towards unrestricted warfare. Four days later enforcement of Prize Regulations in the North Sea was withdrawn; and on 2 October complete freedom was given to attack darkened ships encountered off the British and French coasts. Two days later the Prize Regulations were cancelled in waters extending as far as 15° West, and on 17 October the German Naval Staff gave U-boats permission to attack without warning all ships identified as hostile. The zone where darkened ships could be attacked with complete freedom was extended to 20° West on 19 October. Practically the only restrictions now placed on U-boats concerned attacks on passenger liners and, on 17 November, they too were allowed to be attacked without warning if clearly identifiable as hostile.

Although the phrase was not used, by November 1939 the BdU was practicing unrestricted submarine warfare. Neutral shipping was warned by the Germans against entering the zone which, by American neutrality legislation, was forbidden to American shipping, and against steaming without lights, zigzagging or taking any defensive precautions. The complete practice of unrestricted warfare was not enforced for fear of antagonising neutral powers, particularly the Americans. Admirals Raeder and Dönitz and the German Naval Staff had always wished and intended to introduce unrestricted warfare as rapidly as Hitler could be persuaded to accept the possible consequences.

Dönitz and Raeder accepted the death of the Z Plan upon the outbreak of war. The U-boat programme would be the only portion of it to survive 1939. Both men lobbied Hitler to increase the planned production of submarines to at least 29 per month. The immediate obstacle to the proposals was Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, head of the Four Year Plan

The Four Year Plan was a series of economic measures initiated by Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany in 1936. Hitler placed Hermann Göring in charge of these measures, making him a Reich Plenipotentiary (Reichsbevollmächtigter) whose jurisdiction cut a ...

, commander-in-chief of the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' and future successor to Hitler. Göring would not acquiesce and in March 1940 Raeder was forced to drop the figure from 29 to 25, but even that plan proved illusory. In the first half of 1940, two boats were delivered, increased to six in the final half of the year. In 1941 the deliveries increased to 13 to June, and then 20 to December. It was not until late 1941 the number of vessels began to increase quickly. From September 1939 through to March 1940, 15 U-boats were lost—nine to convoy escorts. The impressive tonnage sunk had little impact on the Allied war effort at that point.

Commander of the submarine fleet

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (, ''BdU''). For the first part of the war, despite disagreements with Raeder where best to deploy his men, Dönitz was given considerable operational freedom for his junior rank.

From September–December 1939 U-boats sank 221 ships for 755,237 gross tons, at the cost of nine U-boats. Only 47 merchant ships were sunk in the

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (, ''BdU''). For the first part of the war, despite disagreements with Raeder where best to deploy his men, Dönitz was given considerable operational freedom for his junior rank.

From September–December 1939 U-boats sank 221 ships for 755,237 gross tons, at the cost of nine U-boats. Only 47 merchant ships were sunk in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe and ...

, a tonnage of 249,195. Dönitz had difficulty in organising Wolfpack operations in 1939. A number of his submarines were lost en route to the Atlantic, through either the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and heavily defended English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. Torpedo failures plagued commanders during convoy attacks. Along with successes against single ships, Dönitz authorised the abandonment of pack attacks in the autumn. The Norwegian Campaign amplified the defects. Dönitz wrote in May 1940, "I doubt whether men have ever had to rely on such a useless weapon." He ordered the removal of magnetic pistols in favour of contact fuses and their faulty depth control systems. In no fewer than 40 attacks on Allied warships, not a single sinking was achieved. The statistics show that from the outbreak of war to approximately the spring, 1940, faulty German torpedoes saved 50–60 ships equating to .

Dönitz was encouraged in operations against warships by the sinking of the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

''Courageous''. On 28 September 1939 he said, "it is not true Britain possesses the means to eliminate the U-boat menace." The first specific operation—named " Special Operation P"—authorised by Dönitz was Günther Prien

Günther Prien (16 January 1908 – presumed 8 March 1941) was a German U-boat commander during World War II. He was the first U-boat commander to receive the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and the first member of the ''Kriegsmarine'' to r ...

's attack on Scapa Flow, which sank the battleship ''Royal Oak''. The attack became a propaganda success though Prien purportedly was unenthusiastic about being used that way. Stephen Roskill wrote, "It is now known that this operation was planned with great care by Admiral Dönitz, who was correctly informed of the weak state of the defences of the eastern entrances. Full credit must also be given to Lieutenant Prien for the nerve and determination with which he put Dönitz's plan into execution."

In May 1940, 101 ships were sunk—but only nine in the Atlantic—followed by 140 in June; 53 of them in the Atlantic for a total of that month. The first six months in 1940 cost Dönitz 15 U-boats. Until mid-1940 there remained a chronic problem with the reliability of the G7e torpedo

The G7e torpedo was the standard electric torpedo used by the German ''Kriegsmarine'' submarines in World War II. It came in 20 different versions, with the initial model G7e(TII) in service at the outbreak of the war. Due to several problems, le ...

. As the battles of Norway and Western Europe raged, the ''Luftwaffe'' sank more ships than the U-boats. In May 1940, German aircraft sank 48 ships (), three times that of German submarines. The Allied evacuations from western Europe and Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

in June 1940 attracted Allied warships in large numbers, leaving many of the Atlantic convoys travelling through the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

unprotected. From June 1940, the German submarines began to exact a heavy toll. In the same month, the ''Luftwaffe'' sank just 22 ships () in a reversal of the previous months.

Germany's defeat of Norway gave the U-boats new bases much nearer to their main area of operations off the Western Approaches. The U-boats operated in groups or 'wolf packs' which were coordinated by radio from land. With the fall of France, Germany acquired U-boat bases at Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town (''Communes of France, commune'') and Port, seaport in the Morbihan Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginn ...

, Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, St Nazaire, and La Pallice

La Pallice (also known as ''grand port maritime de La Rochelle'') is the commercial deep-water port of La Rochelle, France.

During the Fall of France, on 19 June 1940, approximately 6,000 Polish soldiers in exile under the command of Stanisła ...

/La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With ...

and Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

. This extended the range of Type VIIs. Regardless, the war with Britain continued. The admiral remained sceptical of Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

, a planned invasion and expected a long war. The destruction of seaborne trade became German strategy against Britain after the defeat of the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. Hitler was content with The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

and cutting off Britain's imports. Dönitz gained importance as the prospect of a quick victory faded. Dönitz concentrated groups of U-boats against the convoys and had them attack on the surface at night. In addition the Germans were helped by Italian submarines which in early 1941 actually surpassed the number of German U-boats. Having failed to persuade the Nazi leadership to prioritise U-boat construction, a task made more difficult by military victories in 1940 which convinced many people that Britain would give up the struggle, Dönitz welcomed the deployment of 26 Italian submarines to his force. Dönitz complimented Italian bravery and daring, but was critical of their training and submarine designs. Dönitz remarked they lacked the necessary toughness and discipline and consequently were "of no great assistance to us in the Atlantic."

The establishment of German bases on the French Atlantic coast allowed for the prospect of aerial support. Small numbers of German aircraft, such as the long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200

The Focke-Wulf Fw 200 ''Condor'', also known as ''Kurier'' to the Allies (English: Courier), was a German all-metal four-engined monoplane originally developed by Focke-Wulf as a long-range airliner. A Japanese request for a long-range maritime ...

, sank a large number of ships in the Atlantic in the last quarter of 1940. In the long term, Göring proved an insurmountable problem in effecting cooperation between the navy and the ''Luftwaffe''. In early 1941, while Göring was on leave, Dönitz approached Hitler and secured from him a single bomber/maritime patrol unit for the navy. Göring succeeded in overturning this decision and both Dönitz and Raeder were forced to settle for a specialist maritime air command under ''Luftwaffe'' control. Poorly supplied, achieved modest success in 1941, but thereafter failed to have an impact as British counter-measures evolved. Cooperation between the and remained dysfunctional to the war's end. Göring and his unassailable position at the (Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

) prevented all but limited collaboration.

The U-boat fleet's successes in 1940 and early 1941 were spearheaded by a small number of highly trained and experienced pre-war commanders. Otto Kretschmer

Otto Kretschmer (1 May 1912 – 5 August 1998) was a German naval officer and submariner in World War II and the Cold War.

From September 1939 until his capture in March 1941 he sank 44 ships, including one warship, a total of 274,333 tons. For ...

, Joachim Schepke

Joachim Schepke (8 March 1912 – 17 March 1941) was a German U-boat commander during World War II. He was the seventh recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves.

Schepke is credited with having sunk 36 Allied ships. Durin ...

, and Günther Prien

Günther Prien (16 January 1908 – presumed 8 March 1941) was a German U-boat commander during World War II. He was the first U-boat commander to receive the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and the first member of the ''Kriegsmarine'' to r ...

were the most famous, but others included Hans Jenisch

Hans Jenisch (19 October 1913 – 29 April 1982) was a ''Kapitänleutnant'' in Nazi Germany's '' Kriegsmarine'' during the Second World War and a ''Kapitän zur See'' in West Germany's ''Bundesmarine''. He commanded a Type VIIA U-boat, sinking ...

, Victor Oehrn, Engelbert Endrass

Engelbert Endrass (german: Engelbert Endraß) (2 March 1911 – 21 December 1941) was a German U-boat commander in World War II. He commanded the and the , being credited with sinking 22 ships on ten patrols, for a total of of Allied shipping, ...

, Herbert Schultze

Herbert Emil Schultze (24 July 1909 – 3 June 1987), was a German submarine commander during World War II. He commanded the for eight patrols during the early part of the war, sinking of shipping. Schultze was a recipient of the Knight's Cross ...

and Hans-Rudolf Rösing

Hans-Rudolf Rösing (28 September 1905 – 16 December 2004) was a German U-boat commander in World War II and later served in the Bundesmarine of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, of Nazi ...

. Although skilled and with impeccable judgement, the shipping lanes they descended upon were poorly defended. The U-boat force did not escape unscathed. Within the space of several days in March 1941, Prien and Schepke were dead and Kretschmer was a prisoner. All of them fell in battle with a convoy system. The number of boats in the Atlantic remained low. Six fewer existed in May 1940 than in September 1939. In January 1941 there were just six on station in the Atlantic—the lowest during the war, while still suffering from unreliable torpedoes. Dönitz insisted that operations continue while "the smallest prospect of hits" remained.

For his part, Dönitz was involved in the daily operations of his boats and all the major operational level

In the field of military theory, the operational level of war (also called operational art, as derived from russian: оперативное искусство, or operational warfare) represents the level of command that connects the details of ...

decisions. His assistant, Eberhard Godt

Eberhard Godt (15 August 1900 – 13 September 1995) was a German naval officer who served in both World War I and World War II, eventually rising to command the '' Kriegsmarine''s U-boat operations.

Biography

: ''This article incorporates inform ...

, was left to manage daily operations as the war continued. Dönitz was debriefed personally by his captains which helped establish a rapport between leader and led. Dönitz neglected nothing that would make the bond firmer. Often there would be a distribution of medals or awards. As an ex-submariner, Dönitz did not like to contemplate the thought of a man who had done well heading out to sea, perhaps never to return, without being rewarded or receiving recognition. Dönitz acknowledged where decorations were concerned there was no red tape and that awards were "psychologically important."

Intelligence battle

Intelligence played an important role in the Battle of the Atlantic. In general, BdU intelligence was poor. Counter-intelligence was not much better. At the height of the battle in mid-1943 some 2,000 signals were sent from the 110 U-boats at sea. Radio traffic compromised his ciphers by giving the Allies more messages to work with. Furthermore, replies from the boats enabled the Allies to useHigh-frequency direction finding

High-frequency direction finding, usually known by its abbreviation HF/DF or nickname huff-duff, is a type of radio direction finder (RDF) introduced in World War II. High frequency (HF) refers to a radio band that can effectively communicate over ...

(HF/DF, called "Huff-Duff") to locate a U-boat using its radio, track it and attack it. The over-centralised command structure of BdU and its insistence on micro-managing every aspect of U-boat operations with endless signals provided the Allied navies with enormous intelligence. The enormous "paper chase" ross-referencing of materialsoperations pursued by Allied intelligence agencies was not thought possible by BdU. The Germans did not suspect the Allies had identified the codes broken by B-Dienst. Conversely, when Dönitz suspected the enemy had penetrated his own communications BdU's response was to suspect internal sabotage and reduce the number of the staff officers to the most reliable, exacerbating the problem of over-centralisation. In contrast to the Allies, the was suspicious of civilian scientific advisors and generally distrusted outsiders. The Germans were never as open to new ideas or thinking of war in intelligence terms. According to one analyst BdU "lacked imagination and intellectual daring" in the naval war. These Allied advantages failed to avert heavy losses in the June 1940 May 1941 period, known to U-boat crews as the " First Happy Time." In June 1941, 68 ships were sunk in the North Atlantic () at a cost of four U-boats, but the German submarines would not eclipse that number for the remainder of the year. Just 10 transports were sunk in November and December 1941.

On 7 May 1941, the Royal Navy captured the German Arctic meteorological vessel and took its Enigma machine intact, this allowed the Royal Navy to decode U-boat radio communications in June 1941. Two days later the capture of ''U-110'' was an intelligence coup for the British. The settings for high-level "officer-only" signals, "short-signals" () and codes standardising messages to defeat HF/DF fixes by sheer speed were found. Only the ''Hydra'' settings for May were missing. The papers were the only stores destroyed by the crew. The capture on 28 June of another weather ship, , enabled British decryption operations to read radio traffic in July 1941. Beginning in August 1941, Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes ( Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

operatives could decrypt signals between Dönitz and his U-boats at sea without any restriction. The capture of the ''U-110'' allowed the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

to identify individual boats, their commanders, operational readiness, damage reports, location, type, speed, endurance from working up in the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

to Atlantic patrols. On 1 February 1942, the Germans had introduced the M4 cipher machine, which secured communications until it was cracked in December 1942. Even so, the U-boats achieved their best success against the convoys in March 1943, due to an increase in U-boat numbers, and the protection of the shipping lines was in jeopardy. Due to the cracked M4 and the use of radar, the Allies began to send air and surface reinforcements to convoys under threat. The shipping lines were secured, which came as a great surprise to Dönitz. The lack of intelligence and increased numbers of U-boats contributed enormously to Allied losses that year.

Signals security aroused Dönitz's suspicions during the war. On 12 January 1942 German supply submarine ''U-459'' arrived 800 nautical miles west of

Signals security aroused Dönitz's suspicions during the war. On 12 January 1942 German supply submarine ''U-459'' arrived 800 nautical miles west of Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

, well clear of convoy lanes. It was scheduled to rendezvous with an Italian submarine, until intercepted by a warship. The German captain's report coincided with reports of a decrease in sightings and a period of tension between Dönitz and Raeder. The number of U-boats in the Atlantic, by logic, should have increased, not lowered the number of sightings and the reasons for this made Dönitz uneasy. Despite several investigations, the conclusion of the BdU staff was that ''Enigma'' was impenetrable. His signals officer responded to the ''U-459'' incident with answers ranging from coincidence, direction finding to Italian treachery. General Erich Fellgiebel

Fritz Erich Fellgiebel (4 October 1886 – 4 September 1944) was a German Army general of signals and resistance fighter in the 20 July plot to assassinate Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler. In 1929, Fellgiebel became head of the cipher bureau (german: C ...

, Chief Signal Officer of Army High Command and of Supreme Command of Armed Forces (), apparently concurred with Dönitz. He concluded that there was "convincing evidence" that, after an "exhaustive investigation" that the Allied codebreakers had been reading high level communications. Other departments in the navy downplayed or dismissed these concerns. They vaguely implied "some components" of Enigma had been compromised, but there was "no real basis for acute anxiety as regards any compromise of operational security."

American entry

Following Hitler's declaration of war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Dönitz implementedOperation Drumbeat

The "Second Happy Time" (; officially Operation Paukenschlag ("Operation Drumbeat"), and also known among German submarine commanders as the "American Shooting Season") was a phase in the Battle of the Atlantic during which Axis submarines att ...

(). The entry of the United States benefited German submarines in the short term. Dönitz intended to strike close to shore in American and Canadian waters and prevent the convoys—the most effective anti–U-boat system—from ever forming. Dönitz was determined to take advantage of Canadian and American unpreparedness before the situation changed.

The problem inhibiting Dönitz's plan was a lack of boats. On paper he had 259, but in January 1942, 99 were still undergoing sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s and 59 were assigned to training flotillas, leaving only 101 on war operations. 35 of these were under repair in port, leaving 66 operational, of which 18 were low on fuel and returning to base, 23 were en route to areas where fuel and torpedoes needed to be conserved, and one was heading to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. Therefore, on 1 January Dönitz had a fighting strength of 16–25 in the Atlantic (six near to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

on "Norwegian operations"), three in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, three in the Mediterranean and three operating west of Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Dönitz was severely limited to what he could accomplish in American waters in an initial offensive.

From 13 January 1942, Dönitz planned to begin a surprise offensive from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

, image = Baie de la Tour.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Gulf of St. Lawrence from Anticosti National Park, Quebec

, image_bathymetry = Golfe Saint-Laurent Depths fr.svg

, alt_bathymetry = Bathymetry ...

to Cape Hatteras

Cape Hatteras is a cape located at a pronounced bend in Hatteras Island, one of the barrier islands of North Carolina.

Long stretches of beach, sand dunes, marshes, and maritime forests create a unique environment where wind and waves shap ...

. Unknown to him, ULTRA

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. '' ...

had read his Enigma signals and knew the position, size, and intentions of his boats, down to the date the operation was scheduled to begin. The attacks, when they came, were not a surprise. Of the 12 U-boats that began the offensive from the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordf ...

southward, just two survived the war. The operation began the Battle of the St. Lawrence

The Battle of the St. Lawrence involved marine and anti-submarine actions throughout the lower St. Lawrence River and the entire Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Strait of Belle Isle, Anticosti Island and Cabot Strait from May–October 1942, September ...

, a series of battles which lasted into 1944. It remained possible for a U-boat to operate in the Gulf into 1944, but countermeasures were strong. In 1942, the global ratio of ships-to-U-boats sunk in Canadian waters was 112:1. The global average was 10.3:1. The solitary kill was achieved by the RCAF

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

. Canadian operations, as with American efforts, were a failure during this year.

Along with conventional U-boat operations Dönitz authorised clandestine activities in Canadian waters, including spying, mine-laying, and recovery of German prisoners of war (as Dönitz wished to extract information from rescued submariners concerning Allied tactics). All of these things tied down Canadian military power and imposed industrial, fiscal, and psychological costs. The impunity with which U-boats carried out these operations in Canadian waters into 1944 provided a propaganda effect. One of these operations was the well-known Operation Kiebitz

Operation Kiebitz was a failed German operation during World War II to organize the escape of four skilled U-boat commanders from a Canadian prisoner of war camp in Bowmanville, Ontario. The subsequent counter operation by the Royal Canadian Navy ...

to rescue Otto Kretschmer

Otto Kretschmer (1 May 1912 – 5 August 1998) was a German naval officer and submariner in World War II and the Cold War.

From September 1939 until his capture in March 1941 he sank 44 ships, including one warship, a total of 274,333 tons. For ...

.

Even with operational problems great success was achieved in American waters. From January to July 1942, Dönitz's submarines were able to attack unescorted ships off the United States' east coast and in the Caribbean Sea; U-boats sank more ships and tonnage than at any other time in the war. After a convoy system was introduced to protect the shipping, Dönitz shifted his U-boats back to the North Atlantic. The period, known in the U-boat Arm

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the an ...

as the " Second Happy Time", represented one of the greatest naval disasters of all time, and largest defeat suffered by American sea power. The success was achieved with only five U-boats initially which sank 397 ships in waters protected by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

with an additional 23 sunk at the Panama Sea Frontier

The Panama Sea Frontier was a U.S. Navy command responsible during and shortly after World War II for the defense of the Pacific and Atlantic sea approaches to the Panama Canal and naval shore facilities in the Central America region. The Sea Fron ...

. Dönitz put the successes down to the American failure to initialize a blackout along the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

and ship captains' insistence on following peace-time safety procedures. The failure to implement a blackout stemmed from the American government's concern it would affect tourism trade. Dönitz wrote in his memoirs that the lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

s and buoy

A buoy () is a floating device that can have many purposes. It can be anchored (stationary) or allowed to drift with ocean currents.

Types

Navigational buoys

* Race course marker buoys are used for buoy racing, the most prevalent form of yac ...

s "shone forth, though perhaps a little less brightly than usually".

By the time improved American air and naval defences had driven German submarines from American shores, 5,000 Allied sailors had been killed for negligible losses in U-boats. Dönitz ordered simultaneous operations in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

. The ensuing Battle of the Caribbean

The Battle of the Caribbean refers to a naval campaign waged during World War II that was part of the Battle of the Atlantic, from 1941 to 1945. German U-boats and Italian submarines attempted to disrupt the Allied supply of oil and other ma ...

resulted in immediate dividends for U-boats. In a short time, at least 100 transports had been destroyed or sunk. The sinkings damaged inter-island trade substantially. Operation Neuland

Operation Neuland (New Land) was the German Navy's code name for the extension of unrestricted submarine warfare into the Caribbean Sea during World War II. U-boats demonstrated range to disrupt United Kingdom petroleum supplies and United ...

was among the most damaging naval campaigns in the region. Oil refinery

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, lique ...

production in region declined while the tanker fleet suffered losses of up to ten percent within twenty-four hours. However, ultimately Dönitz could not hope to sink more ships than American industry could build, so he targeted the tanker fleet in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

in the hope that depleting oil transports would paralyze shipyard output. 33 transports were sunk in July before Dönitz lost his first crew. The USN introduced effective convoy systems thereafter, ending the "carnage."

Dönitz maintained his demands for the concentration of all his crews in the Atlantic. As the military situation in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and on the Eastern Front began to deteriorate Hitler diverted a number of submarines to the Battle of the Mediterranean upon the suggestions of Admiral Eberhard Weichold

Eberhard Weichold (23 August 1891 – 19 December 1960) was a German naval officer of World War I who, among other commands, was captain of the submarine SM UC-22. On 10 August 1918, Weichold sank the SS ''Polynesien'' while he was in command of ...

. Raeder and Dönitz resisted the deployment to the Mediterranean to no avail. Hitler felt compelled to act against Allied sea forces which were having an enormous impact on Axis supply lines to North Africa. The decision defied logic, for a victory in the Atlantic would end the war in the Mediterranean. The U-boat war in the Mediterranean was a costly failure, despite successes against warships. Approximately 60 crews were lost and only one crew managed to withdraw through the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

. Albrecht Brandi

Albrecht Brandi (20 June 1914 – 6 January 1966) was a German U-boat commander in Nazi Germany's ''Kriegsmarine'' during World War II. Together with Wolfgang Lüth, he was the only ''Kriegsmarine'' sailor who was awarded with the Knight's Cro ...

was one of Dönitz's highest performers but his record is a matter of controversy; post-war records prove systematic over-claiming of sinkings. He survived his boat's sinking and was smuggled to Germany through Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. Dönitz had met his end as a submarine commander in the Mediterranean two decades earlier.

In 1942 Dönitz summed up his philosophy in one simple paragraph; "The enemy's shipping constitutes one single, great entity. It is therefore immaterial where a ship is sunk. Once it has been destroyed it has to be replaced by a new ship; and that's that." The remark was the green light to unrestricted submarine warfare and began the tonnage war

A tonnage war is a military strategy aimed at merchant shipping. The premise is that the enemy has a finite number of ships and a finite capacity to build replacements. The concept was made famous by German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, who wrote:" ...

proper. BdU intelligence concluded the Americans could produce 15,300,000 tons of shipping in 1942 and 1943—two million tons under actual production figures. Dönitz always calculated the worst-case scenario using the highest figures of enemy production potential. Some 700,000 tons per month needed to be sunk to win the war. The "second happy time" reached a peak in June 1942, with 325,000 tons sunk, up from 311,000 in May, 255,000 in April and the highest since the 327,000 tons sunk in March 1942. With support from the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; french: Marine royale canadienne, ''MRC'') is the naval force of Canada. The RCN is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of 2021, the RCN operates 12 frigates, four attack submar ...

, the new convoy systems compelled Dönitz to withdraw his captains to the mid-Atlantic once again. Nevertheless, there was still cause for optimism. B-Dienst had cracked the convoy ciphers and by July 1942 he could call upon 311 boats, 140 operational, to conduct a renewed assault. By October 1942 he had 196 operational from 365. Dönitz's force finally reached the desired number both he and Raeder had hoped for in 1939. Unaware of it, Dönitz and his men were aided by the ULTRA

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. '' ...

blackout. The addition of a fourth rotor to the Enigma left radio detection the only way to gather intelligence on dispositions and intentions of the German naval forces. German code breakers had their own success in the capture of the code book to Cipher Code Number 3 from a merchant ship. It was a treble success for the BdU.

Dönitz was content that he now had the naval power to extend U-boat operations to other areas aside the North Atlantic. The Caribbean, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

ian waters with the coast of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

designated operational theatres. Waters in the southern hemisphere to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

could also be attacked with the new Type IX submarine

The Type IX U-boat was designed by Nazi Germany's ''Kriegsmarine'' in 1935 and 1936 as a large ocean-going submarine for sustained operations far from the home support facilities. Type IX boats were briefly used for patrols off the eastern Unit ...

. The strategy was sound and his tactical ideas were effective. The number of boats available allowed him to form Wolfpacks to comb convoy routes from east to west attacking one when found and pursuing it across the ocean. The pack then refuelled from a U-boat tanker and worked from west to east. Raeder and the operations staff disputed the value in attacking convoys heading westward with empty cargo holds. The tactics were successful but placed great strain on crews who spent up to eight days in constant action.

November 1942 was a new high in the Atlantic. 134 ships were sunk for 807,754 tons. 119 were destroyed by submarines, 83 (508,707 tons) in the Atlantic. The same month Dönitz suffered strategic defeat. His submarines failed to prevent Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

, even with 196 of them operating in the Atlantic. Dönitz considered it a major self-inflicted defeat. Allied morale radically improved after the victories of Torch, the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

and the Battle of Stalingrad; all occurred within days of one another. The U-boat war was the only military success the Germans enjoyed at the end of the year.

Commander-in-chief and Grand Admiral

On 30 January 1943, Dönitz replaced Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy () and (grand admiral) of the Naval High Command (). In a communique to the navy he announced his intentions to retain practical control of the U-boats and his desire to fight to the end for Hitler. Dönitz's inability to delegate control of the U-boat service has been construed as a weakness in the U-boat arm, contributing to the perception that Dönitz was an "impatient warrior", preoccupied with fighting battles and tactics rather than a strategist or organiser. Dönitz's promotion earned Hitler his undying loyalty. For Dönitz, Hitler had given him a "true home-coming at last, to a country in which unemployment appeared to have been abolished, the class war no longer tore the nation apart, and the shame of defeat in 1918 was being expunged." When war came, Dönitz became more firmly wedded to his Nazi faith. Hitler recognised his patriotism, professionalism but above all, his loyalty. Dönitz remained so, long after the war was lost. In so doing, he wilfully ignored the genocidal nature of the regime and claimed ignorance of theHolocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

In the last quarter of 1942, 69 submarines had been commissioned taking the total number to 393, with 212 operational. Dönitz was not satisfied and immediately began a naval construction programme which in contrast to Raeder's, laid all its emphasis on torpedo boats and submarines. Dönitz's proposed expansion ran into difficulties experienced by all of his predecessors; the lack of steel. The navy had no representation in or to Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

's armaments ministry for naval production was the only sphere not under his control. Dönitz understood this worked against the navy because it lacked the elasticity to cope with breakdowns of production at any point, whereas the other services could make good production by compensating one sector at the expense of another. Without any representatives the battle of priorities was left to Speer and Göring. Dönitz had the sense to place U-boat production under Speer on the provision 40 per month were completed. Dönitz persuaded Hitler not to scrap the surface fleet capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s, though they played no role in the Atlantic during his time in command. Dönitz reasoned the destruction of the surface fleet would provide the British with a victory and heap pressure on the U-boats, for these warships were tying down British air and naval forces that would otherwise be sent into the Atlantic.

New construction procedures, dispensing with prototypes and the abandonment of modifications reduced construction times from 460,000-man hours to 260–300,000 to meet Speer's quota. In the spring 1944, the

New construction procedures, dispensing with prototypes and the abandonment of modifications reduced construction times from 460,000-man hours to 260–300,000 to meet Speer's quota. In the spring 1944, the Type XXI submarine

Type XXI submarines were a class of German diesel–electric '' Elektroboot'' (German: "electric boat") submarines designed during the Second World War. One hundred and eighteen were completed, with four being combat-ready. During the war only t ...

was scheduled to reach frontline units. In 1943 however, the Combined Bomber Offensive

The Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) was an Allied offensive of strategic bombing during World War II in Europe. The primary portion of the CBO was directed against Luftwaffe targets which was the highest priority from June 1943 to 1 April 1944. ...

complicated the planned production. Dönitz and Speer were appalled by the destruction of Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, a major construction site. The battles of 1943 and 1944 were fought with the existing VII and Type IX submarine

The Type IX U-boat was designed by Nazi Germany's ''Kriegsmarine'' in 1935 and 1936 as a large ocean-going submarine for sustained operations far from the home support facilities. Type IX boats were briefly used for patrols off the eastern Unit ...

s. The type VII remained the backbone of the fleet in 1943.

At the end of 1942, Dönitz was faced with the appearance of escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

s, and long-range aircraft working with convoy escorts. To protect his boats against the latter, he ordered his boats to restrict their operations to the Mid-Atlantic Gap

The Mid-Atlantic gap is a geographical term applied to an undefended area beyond the reach of land-based RAF Coastal Command antisubmarine (A/S) aircraft during the Battle of the Atlantic in the Second World War. It is frequently known as The Bla ...

, a stretch of ocean out of the range of land‐based aircraft referred to by the Germans as "the black hole." Allied air forces had few aircraft equipped with ASV radar The following meanings of the abbreviation ASV are known to Wikipedia:

* Adaptive servo-ventilation, a treatment for sleep apnea

* Air-to-Surface Vessel radar (also "anti-surface vessel"), aircraft-mounted radars used to find ships and submarines

...

for U-boat detection into April and May 1943, and such units would not exist in Newfoundland until June. Convoys relied on RAF Coastal Command

RAF Coastal Command was a formation within the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was founded in 1936, when the RAF was restructured into Fighter, Bomber and Coastal Commands and played an important role during the Second World War. Maritime Aviation ...

aircraft operating from Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...