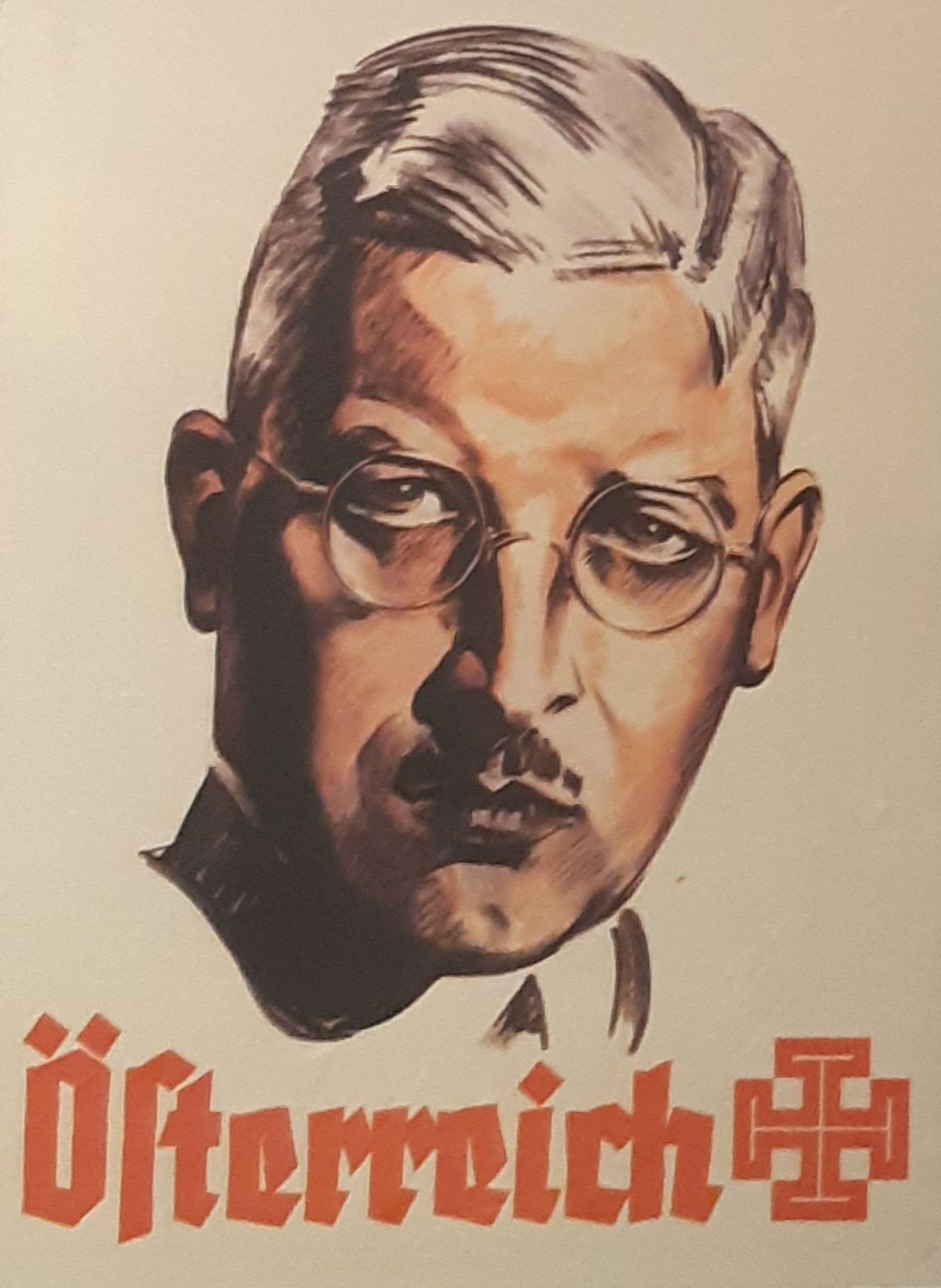

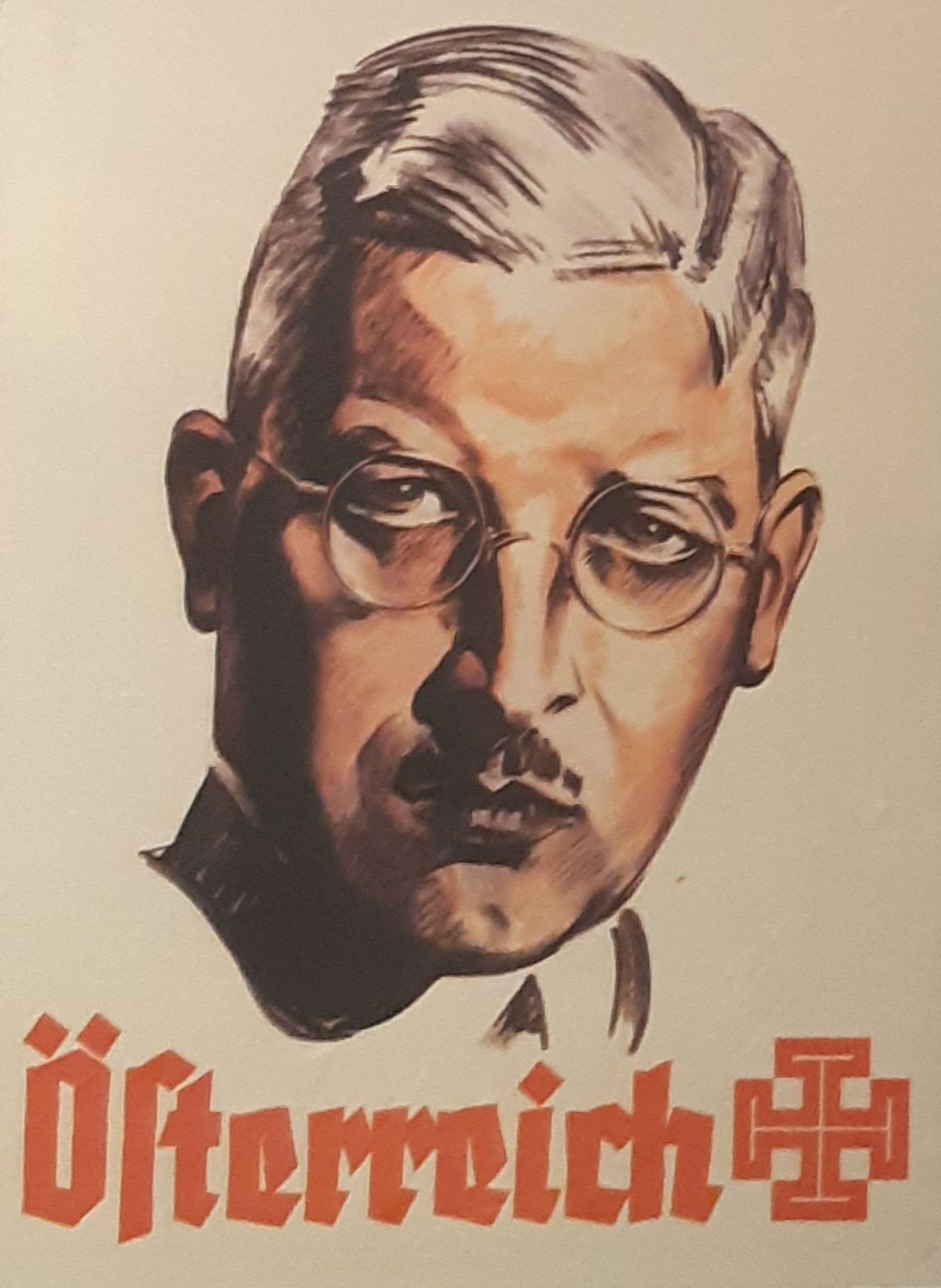

Kurt Schuschnigg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an

On 12 February 1938, Schuschnigg met with Hitler in his Berghof residence in an attempt to smooth the worsening relations between their two countries. To Schuschnigg's surprise, Hitler presented him with a set of demands which, in manner and in terms, amounted to an ultimatum, effectively demanding the handing over of power to the Austrian Nazis. The terms of the agreement, presented to Schuschnigg for immediate endorsement, stipulated the appointment of Nazi sympathiser Arthur Seyss-Inquart as minister of security, which controlled the police. Another pro-Nazi, Dr. Hans Fischböck, was to be named as minister of finance to prepare for economic union between Germany and Austria. A hundred officers were to be exchanged between the Austrian and the German armies. All imprisoned Nazis were to be amnestied and reinstated. In return, Hitler would publicly reaffirm the treaty of 11 July 1936 and Austria's national sovereignty. "The Fuhrer was abusive and threatening, and Schuschnigg was presented with far-reaching demands ..." According to Schuschnigg's memoirs, he was coerced into signing the "agreement" before leaving Berchtesgaden.

The president, Wilhelm Miklas, was reluctant to endorse the agreement but eventually did so. Then he, Schuschnigg and a few key Cabinet members considered a number of options:

:1. The Chancellor resign and the President call on a new Chancellor to form a Cabinet, which would be under no obligation to the commitments of Berchtesgaden.

:2. The Berchtesgaden agreement be carried out under a newly appointed Chancellor.

:3. The agreement be carried out and the Chancellor remain at his post.

In the event, they decided to go with the third option.

On the following day, 14 February, Schuschnigg reorganised his cabinet on a broader basis and included representatives of all former and present political parties. Hitler immediately appointed a new

On 12 February 1938, Schuschnigg met with Hitler in his Berghof residence in an attempt to smooth the worsening relations between their two countries. To Schuschnigg's surprise, Hitler presented him with a set of demands which, in manner and in terms, amounted to an ultimatum, effectively demanding the handing over of power to the Austrian Nazis. The terms of the agreement, presented to Schuschnigg for immediate endorsement, stipulated the appointment of Nazi sympathiser Arthur Seyss-Inquart as minister of security, which controlled the police. Another pro-Nazi, Dr. Hans Fischböck, was to be named as minister of finance to prepare for economic union between Germany and Austria. A hundred officers were to be exchanged between the Austrian and the German armies. All imprisoned Nazis were to be amnestied and reinstated. In return, Hitler would publicly reaffirm the treaty of 11 July 1936 and Austria's national sovereignty. "The Fuhrer was abusive and threatening, and Schuschnigg was presented with far-reaching demands ..." According to Schuschnigg's memoirs, he was coerced into signing the "agreement" before leaving Berchtesgaden.

The president, Wilhelm Miklas, was reluctant to endorse the agreement but eventually did so. Then he, Schuschnigg and a few key Cabinet members considered a number of options:

:1. The Chancellor resign and the President call on a new Chancellor to form a Cabinet, which would be under no obligation to the commitments of Berchtesgaden.

:2. The Berchtesgaden agreement be carried out under a newly appointed Chancellor.

:3. The agreement be carried out and the Chancellor remain at his post.

In the event, they decided to go with the third option.

On the following day, 14 February, Schuschnigg reorganised his cabinet on a broader basis and included representatives of all former and present political parties. Hitler immediately appointed a new

Schuschnigg's career as Austrian Chancellor

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Schuschnigg, Kurt Von 1897 births 1977 deaths 20th-century chancellors of Austria Ministers of defense of Austria People from Riva del Garda Edlers of Austria Austrian emigrants to the United States Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in World War I World War I prisoners of war held by Italy American Roman Catholics Ministers of foreign affairs of Austria People of Carinthian Slovene descent Austrian Roman Catholics Dachau concentration camp survivors Saint Louis University faculty Austrian people of Slovenian descent Christian Social Party (Austria) politicians Sachsenhausen concentration camp survivors Fatherland Front politicians Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion Naturalized citizens of the United States Heads of government who were later imprisoned

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n politician who was the Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of the Federal State of Austria

The Federal State of Austria (; colloquially known as the "") was a continuation of the First Austrian Republic between 1934 and 1938 when it was a one-party state led by the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and politi ...

from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuss (alternatively Dollfuß; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian politician and dictator who served as chancellor of Federal State of Austria, Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and ...

until the 1938 ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

'' with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. Although Schuschnigg considered Austria a "German state" and Austrians to be Germans, he was strongly opposed to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's goal to absorb Austria into the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

and wished for it to remain independent.

When Schuschnigg's efforts to keep Austria independent had failed, he resigned his office. After the Anschluss he was arrested, kept in solitary confinement, and eventually interned in various concentration camps. He was liberated in 1945 by the advancing United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and spent most of the rest of his life in academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.Obituary of Schuschnigg in ''The Times'', London, 19 November 1977 Schuschnigg gained American citizenship in 1956.

Biography

Early life

Schuschnigg was born in Reiff am Gartsee (now Riva del Garda) in the Tyrolean crown land ofAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

(now in Trentino

Trentino (), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento (; ; ), is an Autonomous province#Italy, autonomous province of Italy in the Northern Italy, country's far north. Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the Regions of Italy, region of Tren ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

), the son of Anna Josefa Amalia (Wopfner) and Austrian General Artur von Schuschnigg, member of a long-established Austrian officers' family of Carinthian Slovene descent. The Slovene spelling of the family name is ''Šušnik''.

He received his education at the Stella Matutina Jesuit College in Feldkirch, Vorarlberg

Feldkirch () is a city rights, town in the western Austrian States of Austria, state of Vorarlberg, bordering on Switzerland and Liechtenstein. It is the administrative centre of the Feldkirch (district), Feldkirch district. After Dornbirn, it i ...

. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was taken prisoner at the Italian Front and held captive until September 1919. Subsequently, he studied law at the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

and the University of Innsbruck

The University of Innsbruck (; ) is a public research university in Innsbruck, the capital of the Austrian federal state of Tyrol (state), Tyrol, founded on October 15, 1669.

It is the largest education facility in the Austrian States of Austria, ...

, where he became a member of the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

fraternity A.V. Austria. After graduating in 1922, he practiced as a lawyer in Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; ) is the capital of Tyrol (federal state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the Wipptal, Wipp Valley, which provides access to the ...

.

Political career

Schuschnigg first joined the right-wing Christian Social Party and in 1927 was elected to the Nationalrat, then the youngest parliamentary deputy. Suspicious of the paramilitary ''Heimwehr

The Heimwehr (, ) or Heimatschutz (, ) was a nationalist, initially paramilitary group that operated in the First Austrian Republic from 1920 to 1936. It was similar in methods, organization, and ideology to the Freikorps in Germany. The Heimwe ...

'' organisation, he established the Catholic '' Ostmärkische Sturmscharen'' forces in 1930.

On 29 January 1932, the Christian Social chancellor Karl Buresch appointed Schuschnigg Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, an office he retained in the cabinet of Buresch's successor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuss (alternatively Dollfuß; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian politician and dictator who served as chancellor of Federal State of Austria, Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and ...

, and he also served as Minister of Education

An education minister (sometimes minister of education) is a position in the governments of some countries responsible for dealing with educational matters. Where known, the government department, ministry, or agency that develops policy and deli ...

from 24 May 1933. As justice minister, he openly discussed the abolition of the parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their Election, democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of t ...

and restored the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

. In March 1933, he and Chancellor Dollfuss took the occasion to dissolve the National Council parliament. After the socialist February Uprising of 1934, he had eight insurgents immediately executed, earning him the reputation of an "assassin of the workers". The executions have since been referred to as a vengeful act of judicial murder. Schuschnigg himself later called his orders a "faux pas".

On 1 May 1934, Dollfuss had erected the authoritarian Federal State of Austria

The Federal State of Austria (; colloquially known as the "") was a continuation of the First Austrian Republic between 1934 and 1938 when it was a one-party state led by the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and politi ...

. After Dollfuss was assassinated by the Nazi Otto Planetta during the July Putsch, Schuschnigg on 29 July was appointed Austrian chancellor. Like Dollfuss, Schuschnigg ruled mostly by decree. Although his rule was milder than that of Dollfuss, his policies were not much different from the policies of his predecessor. He had to manage the economy of a near-bankrupt state and to maintain law and order in a country which was forbidden, by the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain, to maintain an army in excess of 30,000 men. At the same time, he had to also cope with armed paramilitary forces in Austria, which owed their allegiance not to the state but to various rival political parties. He also had to be mindful of the growing strength of the Austrian Nazis, who supported Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's ambitions to absorb Austria into Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. His overriding political concern was to preserve Austria's independence within the borders imposed on it by the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which ultimately failed.

John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an Americans, American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-sell ...

wrote in 1936 of Schuschnigg: "It would not be too much to say that he is as much a prisoner of the Italians now s he was during World War I��if the Germans don't get him next week." His policy of counterbalancing the German threat by aligning himself with Austria's southern and eastern neighbours—the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

under the fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

rule of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

—was doomed to failure after Mussolini had sought Hitler's support in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Fascist Italy, Italy against Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is oft ...

and left Austria under the increasing pressure of a massively rearmed Third Reich. Schuschnigg adopted a policy of appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

towards Hitler and called Austria the "better German state", but struggled to keep Austria independent. In July 1936, he signed an Austro-German Agreement, which, among other concessions, allowed the release of imprisoned July Putsch insurgents and the inclusion of the Nazi contact men Edmund Glaise-Horstenau

Edmund Hugo Guilelmus Glaise von Horstenau (also known as Edmund Glaise-Horstenau; 27 February 1882 – 20 July 1946) was an Austrian Nazi politician who became the last vice-chancellor of Austria, appointed by Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg under ...

and Guido Schmidt in the Austrian cabinet. The Nazi Party remained banned; however, the Austrian Nazis gained ground and relations between the two countries deteriorated further. In reaction to Hitler's threats to exercise a controlling influence over Austrian politics, Schuschnigg publicly declared in January 1938:

There is no question of ever accepting Nazi representatives in the Austrian cabinet. An absolute abyss separates Austria from Nazism ... We reject uniformity and centralization. ... Catholicism is anchored in our very soil, and we know but one God: and that is not the State, or the Nation, or that elusive thing, Race.Rumours concerning his involvement in the Von Trapp family’s rise to fame have also come to light. It’s rumoured that upon hearing the Von Trapp family sing over the radio, he invited them to perform in Vienna which greatly helped them in their rise to fame.

''Anschluss''

On 12 February 1938, Schuschnigg met with Hitler in his Berghof residence in an attempt to smooth the worsening relations between their two countries. To Schuschnigg's surprise, Hitler presented him with a set of demands which, in manner and in terms, amounted to an ultimatum, effectively demanding the handing over of power to the Austrian Nazis. The terms of the agreement, presented to Schuschnigg for immediate endorsement, stipulated the appointment of Nazi sympathiser Arthur Seyss-Inquart as minister of security, which controlled the police. Another pro-Nazi, Dr. Hans Fischböck, was to be named as minister of finance to prepare for economic union between Germany and Austria. A hundred officers were to be exchanged between the Austrian and the German armies. All imprisoned Nazis were to be amnestied and reinstated. In return, Hitler would publicly reaffirm the treaty of 11 July 1936 and Austria's national sovereignty. "The Fuhrer was abusive and threatening, and Schuschnigg was presented with far-reaching demands ..." According to Schuschnigg's memoirs, he was coerced into signing the "agreement" before leaving Berchtesgaden.

The president, Wilhelm Miklas, was reluctant to endorse the agreement but eventually did so. Then he, Schuschnigg and a few key Cabinet members considered a number of options:

:1. The Chancellor resign and the President call on a new Chancellor to form a Cabinet, which would be under no obligation to the commitments of Berchtesgaden.

:2. The Berchtesgaden agreement be carried out under a newly appointed Chancellor.

:3. The agreement be carried out and the Chancellor remain at his post.

In the event, they decided to go with the third option.

On the following day, 14 February, Schuschnigg reorganised his cabinet on a broader basis and included representatives of all former and present political parties. Hitler immediately appointed a new

On 12 February 1938, Schuschnigg met with Hitler in his Berghof residence in an attempt to smooth the worsening relations between their two countries. To Schuschnigg's surprise, Hitler presented him with a set of demands which, in manner and in terms, amounted to an ultimatum, effectively demanding the handing over of power to the Austrian Nazis. The terms of the agreement, presented to Schuschnigg for immediate endorsement, stipulated the appointment of Nazi sympathiser Arthur Seyss-Inquart as minister of security, which controlled the police. Another pro-Nazi, Dr. Hans Fischböck, was to be named as minister of finance to prepare for economic union between Germany and Austria. A hundred officers were to be exchanged between the Austrian and the German armies. All imprisoned Nazis were to be amnestied and reinstated. In return, Hitler would publicly reaffirm the treaty of 11 July 1936 and Austria's national sovereignty. "The Fuhrer was abusive and threatening, and Schuschnigg was presented with far-reaching demands ..." According to Schuschnigg's memoirs, he was coerced into signing the "agreement" before leaving Berchtesgaden.

The president, Wilhelm Miklas, was reluctant to endorse the agreement but eventually did so. Then he, Schuschnigg and a few key Cabinet members considered a number of options:

:1. The Chancellor resign and the President call on a new Chancellor to form a Cabinet, which would be under no obligation to the commitments of Berchtesgaden.

:2. The Berchtesgaden agreement be carried out under a newly appointed Chancellor.

:3. The agreement be carried out and the Chancellor remain at his post.

In the event, they decided to go with the third option.

On the following day, 14 February, Schuschnigg reorganised his cabinet on a broader basis and included representatives of all former and present political parties. Hitler immediately appointed a new Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

for Austria, a Nazi Austrian army officer who had just been released from prison in accordance with the terms of the general amnesty stipulated by the Berchtesgaden agreement.

On 20 February, Hitler made a speech before the Reichstag which was broadcast live and which for the first time was relayed also by the Austrian radio network. A key phrase in the speech was: "The German Reich is no longer willing to tolerate the suppression of ten million Germans across its borders."

In Austria, the speech was met with concern and by demonstrations by both pro and anti-Nazi elements. On the evening of 24 February, the Austrian Federal Diet (the Austrian Bundestag), was called into session. In his speech to the Diet, Schuschnigg referred to the July 1936 agreement with Germany and stated: "Austria will go thus far and no further." He ended his speech with an emotional appeal to Austrian patriotism: "Red-White-Red (the colours of the Austrian flag) until we're dead!" The speech was received with disapproval from the Austrian Nazis and they began mobilising their supporters. The headline in ''The Times'' of London was "Schuschnigg's Speech – Nazis Disturbed". The phrase "thus far and no further" was found "disturbing" by the German press.

To resolve the political uncertainty in the country and to convince Hitler and the rest of the world that the people of Austria wished to remain Austrian and independent of the Third Reich, Schuschnigg, with the full agreement of the President and other political leaders, decided to proclaim a plebiscite to be held on 13 March. But the wording of the referendum which had to be responded to with a "Yes" or a "No" turned out to be controversial. It read: "Are you for a free, German, independent and social, Christian and united Austria, for peace and work, for the equality of all those who affirm themselves for the people and Fatherland?"G. Ward Price: ''Year of Reckoning,'' Cassell 1939, London. p. 92

There was another issue which drew the ire of the National Socialists. Although members of Schuschnigg's party (the Fatherland Front) could vote at any age, all other Austrians below the age of 24 were to be excluded under a clause to that effect in the Austrian Constitution. This would shut out from the polls most of the Nazi sympathisers in Austria, since the movement was strongest among the young.

Knowing he was in a bind, Schuschnigg held talks with the leaders of the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

, and agreed to legalise their party and their trade unions in return for their support of the referendum.William Shirer, ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'' (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

The German reaction to the announcement was swift. Hitler first insisted the plebiscite be cancelled. When Schuschnigg reluctantly agreed to scrap it, Hitler demanded his resignation, and insisted that Seyss-Inquart be appointed his successor. This demand President Miklas was reluctant to endorse but eventually, under the threat of immediate armed intervention, it was endorsed as well. Schuschnigg resigned on 11 March, and Seyss-Inquart was appointed Chancellor, but it made no difference; German troops flooded into Austria and were received everywhere by enthusiastic and jubilant crowds. On the morning after the invasion, the London ''Daily Mail''Prison and concentration camp

After initial house arrest followed by solitary confinement atGestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

headquarters, he spent the whole of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Sachsenhausen, then Dachau. In late April 1945, Schuschnigg narrowly escaped an execution order by Adolf Hitler, along with other prominent concentration camp inmates, by being transferred from Dachau to South Tyrol where SS-Totenkopfverbände

(SS-TV; or 'SS Death's Head Battalions') was a major branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary (SS) organisation. It was responsible for administering the Nazi concentration camps, concentration camps and extermination camps of Nazi Germany ...

guards abandoned the prisoners into the hands of some Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

officers, who then freed them. They were then turned over to American troops on 4 May 1945. From there, Schuschnigg and his family were transported, along with many of the ex-prisoners, to the isle of Capri in Italy before being set free.

Later life

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Kurt Schuschnigg was forbidden from joining the ÖVP

The Austrian People's Party ( , ÖVP ) is a Christian-democratic and liberal-conservative political party in Austria.

Since January 2025, the party has been led by Christian Stocker (as an acting leader). It is currently the second-largest p ...

because the party wanted to distance itself from the Austrian dictatorship. Moreover, the ÖVP did not expect their social democratic coalition partner to tolerate Schuschnigg's presence in the party, since after the civil war of 1934 he had had many social democrats killed as Minister of Justice. Schuschnigg emigrated to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, where he was sheltered at the chateau estate Vouziers of the Desloge family

The Desloge family, () centered mostly in Missouri and especially at St. Louis, rose to wealth through international commerce, sugar refinery, sugar refining, oil well, oil drilling, fur trade, fur trading, mineral mining, sawmill, saw milling, ma ...

in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

; and then he became a professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other tertiary education, post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin ...

of political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and Power (social and political), power, and the analysis of political activities, political philosophy, political thought, polit ...

at Saint Louis University

Saint Louis University (SLU) is a private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1818 by Louis William Valentine DuBourg, it is the oldest university west of the Missi ...

from 1948 to 1967. He became an American citizen in 1956.

His first wife Herma died in a car accident in 1935. He remarried in 1938, but lost his second wife, Vera Fugger von Babenhausen (née Countess Czernin), in 1959.

Kurt Schuschnigg went back to Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

where he downplayed his time exercising dictatorial powers as chancellor and tried to justify the regime.

Schuschnigg died at Mutters, near Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; ) is the capital of Tyrol (federal state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the Wipptal, Wipp Valley, which provides access to the ...

, in 1977.

Awards and decorations

* Austria-Hungary: Military Merit Cross * Austria-Hungary: Military Merit Medal * Austria-Hungary: Karl Troop Cross * Austria-Hungary: Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria, Pre-war version (2 awards) * Holy See: Order of St. Gregory the Great, Knight Grand Cross * Kingdom of Italy: Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, Knight Grand Cordon * Czechoslovakia: Order of the White Lion, Knight Grand Cross * other medalsWorks

* ''My Austria'' (1937) * ''Austrian Requiem'' (1946) * ''International Law'' (1959) * ''The Brutal Takeover'' (1969) In German * ''Dreimal Österreich''. Verlag Thomas Hegner, Wien 1937. * ''Ein Requiem in Rot-Weiß-Rot. Aufzeichnungen des Häftlings Dr. Auster''. Amstutz, Zürich 1946. * ''Österreich. Eine historische Schau''. Verlag Thomas Morus, Sarnen 1946. * ''Im Kampf gegen Hitler. Die Überwindung der Anschlußidee''. Amalthea, Wien 1988, . * Dieter A. Binder (Hrsg.): ''Sofort vernichten. Die vertraulichen Briefe Kurt und Vera von Schuschnigg 1938–1945''. Amalthea, Wien 1997, .Notes

References

Further reading

* David Faber. ''Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II''. Simon & Schuster, 2009, pp. 104–38, . *G. Ward Price. ''Year of Reckoning''. London: Cassell 1939. * Hopfgartner, Anton. ''Kurt Schuschnigg. Ein Mann gegen Hitler.'' Graz/Wien: Styria, 1989, . * Lucian O. Meysels. ''Der Austrofaschismus – Das Ende der ersten Republik und ihr letzter Kanzler''. Wien-München: Amalthea, 1992, . * Schuschnigg, Kurt von. ''Der lange Weg nach Hause. Der Sohn des Bundeskanzlers erinnert sich. Aufgezeichnet von Janet von Schuschnigg''. Wien: Amalthea, 2008, . * * Jack Bray. ''Alone Against Hitler: Kurt Von Schuschnigg's Fight to Save Austria from the Nazis.'' Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 2020, .External links

Schuschnigg's career as Austrian Chancellor

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Schuschnigg, Kurt Von 1897 births 1977 deaths 20th-century chancellors of Austria Ministers of defense of Austria People from Riva del Garda Edlers of Austria Austrian emigrants to the United States Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in World War I World War I prisoners of war held by Italy American Roman Catholics Ministers of foreign affairs of Austria People of Carinthian Slovene descent Austrian Roman Catholics Dachau concentration camp survivors Saint Louis University faculty Austrian people of Slovenian descent Christian Social Party (Austria) politicians Sachsenhausen concentration camp survivors Fatherland Front politicians Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion Naturalized citizens of the United States Heads of government who were later imprisoned