Johnston's Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, the Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion, was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the

''

Mormons began settling in what is now

Mormons began settling in what is now

During this period, the leadership of the LDS Church supported

During this period, the leadership of the LDS Church supported

/ref> This meeting may have been Young's attempt to win Indian support against the United States and refrain from raids against Mormon settlements. In sermons on August 16 and again one month later, Young publicly urged the emigrant wagon trains to keep away from the Territory. Despite Young's efforts, Indians attacked Mormon settlements during the course of the Utah War, including a raid on Fort Limhi on the Salmon River in

Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

and the armed forces of the US government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ...

. The confrontation lasted from May 1857 to July 1858. The conflict primarily involved Mormon settlers and federal troops, escalating from tensions over governance and autonomy within the territory. There were several casualties, predominantly non-Mormon civilians. Although the war featured no significant military battles, it included the Mountain Meadows Massacre

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

, where Mormon militia members disarmed and murdered about 120 settlers traveling to California.

The resolution of the Utah War came through negotiations that permitted federal troops to enter Utah Territory in exchange for a pardon granted to the Mormon settlers for any potential acts of rebellion. This settlement significantly reduced the tensions and allowed for the re-establishment of federal authority over the territory while largely preserving Mormon interests and autonomy. At the same time the conflict was widely seen as a disaster for President Buchanan, who many felt botched the situation, and it became known as "Buchanan's Blunder" in later years. Many believe the war along with Buchanan's failings contributed to the rising tensions that would lead to the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in 1861.

Overview

In 1857–1858,President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

sent U.S. forces to the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

in what became known as the Utah Expedition. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, denomination and the ...

(LDS Church), also known as Mormons or Latter-day Saints, fearful that the large U.S. military force had been sent to annihilate them and having faced persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in other areas, made preparations for defense. Though bloodshed was to be avoided, and the U.S. government also hoped that its purpose might be attained without the loss of life, both sides prepared for war. The Mormons manufactured or repaired firearms, prepared war scythe

A war scythe or military scythe is a form of polearm with a curving single-edged blade with the cutting edge on the concave side of the blade. Its blade bears a superficial resemblance to that of an agricultural scythe from which it is likely ...

s, and burnished and sharpened long-unused saber

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

s.

Rather than engaging the Army directly, the Mormon strategy was one of hindering and weakening them. Daniel H. Wells, Lieutenant-General of the Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized Latter-day Saints Militias and Military Units, militia of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States from February 4, 1841 until January 29, 1845. Its main function was the defense of Nauvoo and surrounding Latte ...

, instructed Major Joseph Taylor:

On ascertaining the locality or route of the troops, proceed at once to annoy them in every possible way. Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping by night surprises; blockade the road by felling trees or destroying the river fords where you can. Watch for opportunities to set fire to the grass on their windward so as, if possible, to envelop their trains. Leave no grass before them that can be burned. Keep your men concealed as much as possible, and guard against surprise.The Mormons blocked the army's entrance into the

Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County, Utah, Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City, Utah, Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Utah, Murray, Sandy, Uta ...

, and weakened the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

by hindering their receiving of provisions.

The confrontation between the Mormon militia, called the Nauvoo Legion, and the U.S. Army involved some destruction of property and a few brief skirmishes in what is today southwestern Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, but no battles occurred between the contending military forces.

At the height of the tensions, on September 11, 1857, at least 120 California-bound settlers from Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

and other states, including unarmed men, women, and children, were killed in remote southwestern Utah by a group of local Mormon militia. The Mormon militia responsible for the massacre first claimed that the migrants were killed by Natives

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

but it was proven otherwise. This event was later called the Mountain Meadows Massacre

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

, and the motives behind the incident remain unclear.

The Aiken Massacre took place the following month. In October 1857, Mormons arrested six Californians traveling through Utah and charged them with being spies for the U.S. Army. They were released but were later murdered and robbed of their stock and $25,000.

Other incidents of violence have also been linked to the Utah War, including a Native American attack on the Mormon mission of Fort Lemhi in eastern Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

, modern-day Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

. They killed two Mormons and wounded several others. The historian Brigham Madsen notes, " e responsibility for the ort Limhi raidlay mainly with the Bannock

Bannock may mean:

* Bannock (British and Irish food), a kind of bread, cooked on a stone or griddle served mainly in Scotland but consumed throughout the British Isles

* Bannock (Indigenous American food), various types of bread, usually prepare ...

."William G. Hartley, "Dangerous Outpost: Thomas Corless and the Fort Limhi/Salmon River Mission"''

Mormon Historical Studies

The Ensign Peak Foundation (formerly the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation) is an independent organization that seeks to contribute to the memorialization of sites important to the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The o ...

'', Fall 2001, pp 135–162. Retrieved 2008-04-10. David Bigler concludes that the raid was probably caused by members of the Utah Expedition who were trying to replenish their stores of livestock that had been stolen by Mormon raiders.

Taking all incidents into account, William MacKinnon estimated that approximately 150 people died as a direct result of the year-long Utah War, including the 120 migrants killed at Mountain Meadows. He points out that this was close to the number of people killed during the seven-year contemporaneous struggle in "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

".

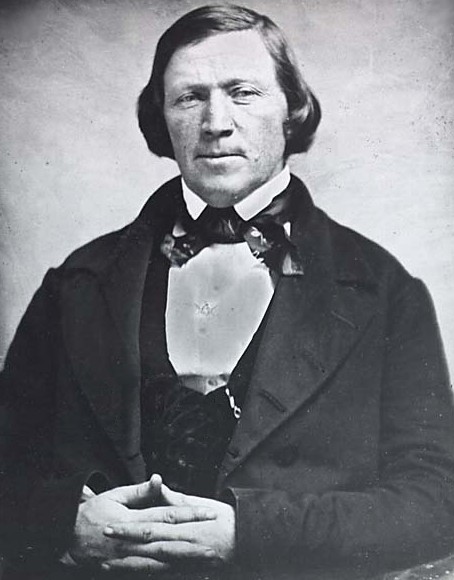

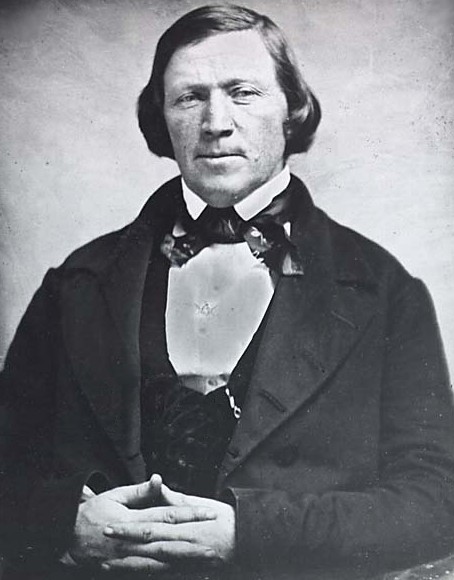

In the end, negotiations between the United States and the Latter-day Saints resulted in a full pardon for the Latter-day Saints (except those involved in the Mountain Meadows murders), the transfer of Utah's governorship from church president Brigham Young

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1847 until h ...

to non-Mormon Alfred Cumming, and the peaceful entrance of the U.S. Army into Utah.

Background

Exodus to the Utah Territory

Mormons began settling in what is now

Mormons began settling in what is now Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

(then part of Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

in the Centralist Republic of Mexico

The Centralist Republic of Mexico (), or in the anglophone scholarship, the Central Republic, officially the Mexican Republic (), was a unitary political regime established in Mexico on 23 October 1835, under a new constitution known as the () ...

) in the summer of 1847. Mormon pioneers began leaving the United States for Utah after a series of severe conflicts with neighboring communities in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

resulted, in 1844, in the death of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith, the founder and leader of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, United States, on June 27, 1844, while awaiting trial in the town jail on charges of treason.

The ...

, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by ...

.

Brigham Young

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1847 until h ...

and other LDS Church leaders believed that the isolation of Utah would secure the rights of Mormons and would ensure the free practice of their religion. Although the United States had gained control

Control may refer to:

Basic meanings Economics and business

* Control (management), an element of management

* Control, an element of management accounting

* Comptroller (or controller), a senior financial officer in an organization

* Controlling ...

of the settled parts of Alta California and Nuevo México in 1846 in the early stages of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, legal transfer of the Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession () is the region in the modern-day Western United States that Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United S ...

to the U.S. came only with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

ending the war in 1848. LDS Church leaders understood that they were not "leaving the political orbit of the United States", nor did they want to. When gold was discovered in California in 1848 at Sutter's Mill

Sutter's Mill was a water-powered sawmill on the bank of the South Fork American River in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California. It was named after its owner John Sutter. A worker constructing the mill, James W. Marshall, found go ...

, which sparked the famous California Gold Rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

, thousands of migrants began moving west on trails that passed directly through territory settled by Mormon pioneers. Although the migrants brought opportunities for trade, they also ended the Mormons' short-lived isolation.

In 1849, the Mormons proposed that a large part of the territory that they inhabited be incorporated into the United States as the State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously , as recorded in the Deseret alphabet spelling 𐐔𐐯𐑅𐐨𐑉𐐯𐐻) was a proposed U.S. state, state of the United States promoted by leaders of the Church of Jesus Chri ...

. Their primary concern was to be governed by men of their own choosing rather than "unsympathetic carpetbag appointees", who they believed would be sent from Washington, D.C. if their region were given territorial status, as was customary. They believed that only through a state run by church leadership could they maintain their religious freedom. The U.S. Congress created the Utah Territory as part of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

selected Brigham Young, the LDS Church's president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

, as the first governor of the Territory. The Mormons were pleased by the appointment, but gradually the amicable relationship between Mormons and the federal government broke down.

Polygamy, popular sovereignty, and slavery

During this period, the leadership of the LDS Church supported

During this period, the leadership of the LDS Church supported polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

, which Mormons called "plural marriage

Polygamy (called plural marriage by Latter-day Saints in the 19th century or the Principle by modern fundamentalist practitioners of polygamy) was practiced by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) for more ...

". An estimated 20% to 25% of Latter-day Saints were members of polygamous households, with the practice involving approximately one-third of Mormon women who reached marriageable age. The Mormons in territorial Utah viewed plural marriage as religious doctrine until 1890, when it was removed as an official practice of the church by Wilford Woodruff

Wilford Woodruff Sr. (March 1, 1807September 2, 1898) was an American religious leader who served as the fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1889 until his death. He ended the public practice of ...

.

However, the rest of American society rejected polygamy, and some commentators accused the Mormons of gross immorality. During the Presidential election of 1856

The following elections occurred in the year 1856.

North America Central America

* 1856 Honduran presidential election

* 1856 Salvadoran presidential election

United States

* California's at-large congressional district

* 1856 New York state e ...

a key plank of the newly formed Republican Party's platform

Platform may refer to:

Arts

* Platform, an arts centre at The Bridge, Easterhouse, Glasgow

* ''Platform'' (1993 film), a 1993 Bollywood action film

* ''Platform'' (2000 film), a 2000 film by Jia Zhangke

* '' The Platform'' (2019 film)

* Pla ...

was a pledge "to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism: polygamy and slavery". The Republicans associated the Democratic principle of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

with the party's acceptance of polygamy in Utah and turned this accusation into a formidable political weapon.

Popular sovereignty was the theoretical basis of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

and the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

of 1854. This concept was meant to remove the divisive issue of slavery in the Territories from the national debate, allowing local decision-making and forestalling armed conflict between the North and South. But during the campaign, the Republican Party denounced the theory as protecting polygamy. Such leading Democrats as Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

, formerly an ally of the Latter-day Saints began to denounce Mormonism in order to save the concept of popular sovereignty for issues related to slavery. The Democrats believed that American attitudes toward polygamy had the potential of derailing the compromise on slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. For the Democrats, attacks on Mormonism had the dual purpose of disentangling polygamy from popular sovereignty and distracting the nation from the ongoing battles over slavery.

In March 1852, the Utah Territory passed Acts that legalized black slavery and Indian slavery.

Theodemocracy

Many east-coast politicians, such as U.S. President James Buchanan, were alarmed by the semi-theocratic

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's daily a ...

dominance of the Utah Territory under Brigham Young. Young had been appointed territorial Governor by Millard Fillmore.

In addition to popular election, many early LDS Church leaders received quasi-political administrative appointments at both the territorial and federal level that coincided with their ecclesiastical roles, including the powerful probate judge

A probate court (sometimes called a surrogate court) is a court that has competence in a jurisdiction to deal with matters of probate and the administration of estates. In some jurisdictions, such courts may be referred to as orphans' courts o ...

s. In analogy to the federal procedure, these executive and judicial appointments were confirmed by the Territorial Legislature, which largely consisted of popularly elected Latter-day Saints. Additionally, LDS Church leaders counseled Latter-day Saints to use ecclesiastical arbitration

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

to resolve disputes among church members before resorting to the more explicit legal system. Both President Buchanan and the U.S. Congress saw these acts as obstructing, if not subverting, the operation of legitimate institutions of the United States.

Numerous newspaper articles continued sensationalizing Mormon beliefs and exaggerated earlier accounts of conflicts with frontier settlers. These stories led many Americans to believe that Mormon leaders were petty tyrants and that Mormons were determined to create a Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

, polygamous kingdom in the newly acquired territories.

Many felt that these sensationalized beliefs, along with early communitarian

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relation ...

practices of the United Order

In the Latter-day Saint movement, the United Order (also called the United Order of Enoch) was one of several 19th-century church collectivist programs. Early versions of the Order beginning in 1831 attempted to fully implement the law of consecr ...

, also violated the principles of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

as well as the philosophy of laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

economics. James Strang

James Jesse Strang (March 21, 1813 – July 9, 1856) was an American religious leader, politician and self-proclaimed monarch. He served as a member of the Michigan House of Representatives from 1853 until his assassination.

In 1844, he said he ...

, a rival to Brigham Young who also claimed succession to the leadership of the church after Joseph Smith's death, elevated these fears by proclaiming himself a king and resettling his followers on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

, after the main body of the LDS Church had fled to Utah.

People also believed that Brigham Young maintained power through a paramilitary organization called the Danites

The Danites were a fraternal organization founded by Latter Day Saint members in June 1838, in the town of Far West, Caldwell County, Missouri. During their period of organization in Missouri, the Danites operated as a vigilante group and took ...

. The Danites were formed by a group of Mormons in Missouri in 1838. Most scholars believe that following the end of the Mormon War in the winter of 1838, the unit was partially disbanded. These factors contributed to the popular belief that Mormons "were oppressed by a religious tyranny and kept in submission only by some terroristic arm of the Church ... oweverno Danite band could have restrained the flight of freedom-loving men from a Territory possessed of many exits; yet a flood of emigrants poured ''into'' Utah each year, with only a trickle ... ebbing back."

Federal appointees

These circumstances were not helped by the relationship between "Gentile

''Gentile'' () is a word that today usually means someone who is not Jewish. Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, have historically used the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is used as a synony ...

" (non-Mormon) federal appointees and the Mormon territorial leadership. The territory's Organic Act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes an administrative agency or local government, for example, the laws that established territory of the United States and specified how they are to ...

held that the governor, federal judges, and other important territorial positions were to be filled by appointees chosen by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, but without any reference to the will of Utah's population—as was standard for all territorial administration.

Some federal officials sent by the President maintained essentially harmonious relationships with the Mormons. For instance, from 1853 to 1855, the territorial supreme court was composed of two non-Mormons and one Mormon. However, both of these non-Mormons were well respected in the Latter-day Saint community and were genuinely mourned for their deaths. Others had severe difficulties adjusting to the Mormon-dominated territorial government and the unique Mormon culture. Historian Norman Furniss writes that although some of these appointees were basically honest and well-meaning, many were highly prejudiced against the Mormons even before they arrived in the territory and woefully unqualified for their positions, while a few were down-right reprobates.

On the other hand, the Mormons had no patience for the federal domination entailed by territorial status and often showed defiance toward the representatives of the federal government. In addition, the Saints sincerely declared their loyalty to the United States and celebrated the Fourth of July

Independence Day, known colloquially as the Fourth of July, is a federal holiday in the United States which commemorates the ratification of the Declaration of Independence by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing th ...

every year with unabashed patriotism, but they were undisguisedly critical of the federal government, which they felt had driven them out from their homes in the east. Like the contemporary abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

, Latter-day Saint leaders declared that the judgments of God would be meted out upon the nation for its unrighteousness. Brigham Young echoed the opinion of many Latter-day Saints when he declared "I love the government and the Constitution of the United States, but I do not love the damned rascals that administer the government."

The Mormons also maintained a governmental and legal regime in "Zion", which they believed was perfectly permissible under the Constitution, but which was fundamentally different from that espoused in the rest of the country.

The Latter-day Saints and federal appointees in the Territory faced continual dispute. These conflicts regarded relations with the Indians (who often differentiated between "Americans" and "Mormons"), acceptance of the common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

, the criminal jurisdiction of probate court

A probate court (sometimes called a surrogate court) is a court that has competence in a jurisdiction to deal with matters of probate and the administration of estates. In some jurisdictions, such courts may be referred to as orphans' courts o ...

s, the Mormon use of ecclesiastical courts rather than the federal court system for civil matters, the legitimacy of land titles, water rights, and various other issues. Many of the federal officers were also appalled by the practice of polygamy and the Mormon belief system in general and would harangue the Mormons for their "lack of morality" in public addresses. This already tense situation was further exacerbated by a period of intense religious revival starting in late 1856 dubbed the "Mormon Reformation

The Mormon Reformation was a period of renewed emphasis on spirituality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a centrally-directed movement, which called for a spiritual reawakening among church members. It took p ...

".

Beginning in 1851, a number of federal officers, some claiming that they feared for their physical safety, left their Utah appointments for the east. The stories of these " Runaway Officials" convinced the new President that the Mormons were nearing a state of rebellion against the authority of the United States. According to LDS historians James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, the most influential information came from William W. Drummond, an associate justice of the Utah territorial supreme court who began serving in 1854. Drummond's letter of resignation of March 30, 1857, contained charges that Young's power set aside the rule of law in the territory, that the Mormons had ignored the laws of Congress and the Constitution, and that male Mormons acknowledged no law but the priesthood.

This account was further supported by Territorial Chief Justice Kinney in reports to Washington, where he recited examples of what he believed to be Brigham Young's perversion of Utah's judicial system and further urged his removal from office and the establishment of a one-regiment U.S. Army garrison in the territory. There were further charges of treason, battery, theft, and fraud made by other officials, including Federal Surveyors and Federal Indian Agents. Furniss states that most federal reports from Utah to Washington "left unclear whether the ormonshabitually kicked their dogs; otherwise, their calendar of infamy in Utah was complete".

As early as 1852, Dr. John M. Bernhisel, Utah's Mormon delegate to Congress, had suggested that an impartial committee be sent to investigate the actual conditions in the territory. This call for an investigation was renewed during the crisis of 1857 by Bernhisel and even by Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

. However, the President would not wait. Under massive popular and political pressure, President Buchanan decided to take decisive action against the Mormons soon after his inauguration on March 4, 1857.

President Buchanan first decided to appoint a new governor in place of Brigham Young. The position was offered to several individuals who refused, and the President finally settled on Alfred Cumming during the summer. While Young became aware of the change in territorial administration through press reports and other sources, he received no official notification of his replacement until Cumming arrived in the Territory in November 1857. Buchanan also decided to send a force of 2,500 army troops to build a post in Utah and to act as a posse comitatus

The ''posse comitatus'' (from Latin for "the ability to have a retinue or gang"), frequently shortened to posse, is in common law a group of people mobilized to suppress lawlessness, defend the people, or otherwise protect the place, property, ...

once the new governor had been installed. They were ordered not to take offensive action against the Mormons but to enter the territory, enforce the laws under the direction of the new governor, and defend themselves if attacked.

Troop movements

July–November 1857: tactical standoff

Preparations

Although the Utah Expedition had begun to gather as early as May under orders from GeneralWinfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, the first soldiers did not leave Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas, until 18 July 1857. The troops were originally led by Gen. William S. Harney. However, affairs in "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

" forced Harney to remain behind to deal with skirmishes between pro-slavery and free-soiler militants. The Expedition's cavalry, the 2nd Dragoons, was kept in Kansas for the same reason. Because of Harney's unavailability, Col. Edmund Alexander was charged with the first detachment of troops headed for Utah. However, the overall command was assigned to Col. Albert Sidney Johnston

General officer, General Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) was an American military officer who served as a general officer in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States ...

, who did not leave Kansas until much later. As it was, July was already far into the campaigning season, and the army and their supply train were unprepared for winter in the Rocky Mountains. The army was not given instructions on how to react in case of resistance.

The Mormons' lack of information on the army's mission created apprehension and led to their defensive preparations. While rumors spread during the spring that an army was coming to Utah and Brigham Young had been replaced as governor, this was not confirmed until late July. Mormon mail contractors, including Porter Rockwell

Orrin Porter Rockwell (June 28, 1813 or June 25, 1815 – June 9, 1878) was a figure of the Wild West period of American history. A lawman in the Utah Territory, he was nicknamed ''Old Port'', ''The Destroying Angel of Mormondom'' and ''Modern-da ...

and Abraham O. Smoot

Abraham Owen Smoot (February 17, 1815 – March 6, 1895) was an American pioneer, businessman, religious leader, and politician. He spent his early life in the Southern United States and was one of seven children. After being baptized a mem ...

, received word in Missouri that their contract was canceled and that the Army was on the move. The men quickly returned to Salt Lake City and notified Brigham Young that U.S. Army units were marching on the Mormons. Young announced the approach of the army to a large group of Latter-day Saints gathered in Big Cottonwood Canyon

Big Cottonwood Canyon is a canyon in the Wasatch Range southeast of Salt Lake City in the U.S. state of Utah. The -long canyon provides hiking, biking, picnicking, rock-climbing, camping, and fishing in the summer. Its two ski resorts, Bright ...

for Pioneer Day

Pioneer Day is an official holiday celebrated on July 24 in the U.S. state of Utah, with some celebrations taking place in regions of surrounding states originally settled by Mormon pioneers. It commemorates the entry of Brigham Young and the f ...

celebrations on 24 July.

Young disagreed with Buchanan's choices for governor of the territory. Although Young's secular position simplified his administration of the Territory, he believed his religious authority was more important among a nearly homogeneous population of Mormons. Young and the Mormon community feared renewed persecution and possibly annihilation by a large body of federal troops. Mormons remembered previous conflicts when they had lived near numerous non-Mormons. In 1838, they were driven from Missouri into Illinois under the direction of the Governor of Missouri, who issued the infamous Extermination Order. Mormons' state of mind was further alarmed when they learned in late June 1857 that LDS Apostle Parley P. Pratt had recently been murdered while serving a mission in Arkansas.

Fearing the worst, Young ordered residents throughout Utah territory to prepare for evacuation, making plans to burn their homes and property and stockpile food and stock feed. Guns were manufactured, and ammunition was cast. Mormon colonists in small outlying communities in the Carson Valley

Douglas County is a county in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Nevada. As of the 2020 census, the population was 49,488. Its county seat is Minden. Douglas County comprises the Gardnerville Ranchos, NV Micropolitan Statistical Area ...

and San Bernardino, California

San Bernardino ( ) is a city in and the county seat of San Bernardino County, California, United States. Located in the Inland Empire region of Southern California, the city had a population of 222,101 in the 2020 census, making it the List of ...

were ordered to leave their homes to consolidate with the main body of Latter-day Saints in Northern and Central Utah. All LDS missionaries serving in the United States and Europe were recalled. Young also sent George A. Smith to the settlements of southern Utah to prepare them for action. Young's strategies to defend the Saints vacillated between all-out war, a more limited confrontation, and retreat.

An alliance with the Indians was central to Young's strategy for war, although his relations with them had been strained since the settlers' arrival in 1847. Young had generally adopted a policy of conversion and conciliation towards native tribes. Some Mormon leaders encouraged intermarriage with the Indians so that the two peoples might "unite together" and their "interests become one".

Between August 30 and September 1, Young met with Indian delegations and gave them permission to take all of the livestock then on the northern and southern trails into California (the Fancher Party was at that time on the southern trail)."Dinnick Huntington Diary, August 30 and September 1, 1857"/ref> This meeting may have been Young's attempt to win Indian support against the United States and refrain from raids against Mormon settlements. In sermons on August 16 and again one month later, Young publicly urged the emigrant wagon trains to keep away from the Territory. Despite Young's efforts, Indians attacked Mormon settlements during the course of the Utah War, including a raid on Fort Limhi on the Salmon River in

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

in February 1858 and attacks in Tooele County just west of Great Salt Lake City.

In early August, Young re-activated the Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized Latter-day Saints Militias and Military Units, militia of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States from February 4, 1841 until January 29, 1845. Its main function was the defense of Nauvoo and surrounding Latte ...

. This was the Mormon militia created during the conflict in Illinois. The Nauvoo Legion was under the command of Daniel H. Wells and consisted of all able-bodied men between 15 and 60. Young ordered the Legion to take delaying actions, essentially harassing federal troops. He planned to buy time for the Mormon settlements to prepare for either battle or evacuation and create a window for negotiations with the Buchanan Administration. Thus, in mid-August, militia Colonel Robert T. Burton and a reconnaissance unit were sent east from Salt Lake City with orders to observe the oncoming American regiments and protect LDS emigrants traveling on the Mormon Trail

The Mormon Trail is the route from Illinois to Utah on which Mormon pioneers (members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) traveled from 1846 to 1869. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails Syst ...

.

Captain Van Vliet

On July 18, 1857, U.S. Army Captain Stewart Van Vliet, an assistant quartermaster, and a small escort were ordered to proceed directly from Kansas to Salt Lake City, ahead of the main body of troops. Van Vliet carried a letter to Young from General Harney ordering Young to make arrangements for the citizens of Utah to accommodate and supply the troops once they arrived. However, Harney's letter did not mention that Young had been replaced as governor, nor did it detail what the mission of the troops would be once they arrived, and these omissions sparked even greater distrust among the Saints. On his journey, reports reached Van Vliet that his company might be in danger from Mormon raiders on the trail. The Captain, therefore, left his escort and proceeded alone. Van Vliet arrived in Salt Lake City on September 8. Historian Harold Schindler states that his mission was to contact Governor Young and inform him of the expedition's mission: to escort the new appointees, to act as aposse comitatus

The ''posse comitatus'' (from Latin for "the ability to have a retinue or gang"), frequently shortened to posse, is in common law a group of people mobilized to suppress lawlessness, defend the people, or otherwise protect the place, property, ...

and to establish at least two and perhaps three new U.S. Army camps in Utah. Conversing with Van Vliet, Young denied complicity in the destruction of the law offices of U.S. Federal Judge Stiles and expressed concern that he (Young) might suffer the same fate as the previous Mormon leader, Joseph Smith, to which Van Vliet replied, "I do not think it is the intention of the government to arrest you," said Van Vliet, "but to install a new governor of the territory". Van Vliet's instructions were to buy provisions for the troops and to inform the people of Utah that the troops would only be employed as a posse comitatus when called on by the civil authority to aid in the execution of the laws.

Van Vliet's arrival in Salt Lake City was welcomed cautiously by the Mormon leadership. Van Vliet had been previously known by the Latter-day Saints in Iowa, and they trusted and respected him. However, he found the residents of Utah determined to defend themselves. He interviewed leaders and townspeople and "attended Sunday services, heard emotional speeches, and saw the Saints raise their hands in a unanimous resolution to guard against any 'invader. Van Vliet found it impossible to persuade resentful Mormon leaders that the Army had peaceful intentions. He quickly recognized that supplies or accommodations for the Army would not be forthcoming. But Young told Van Vliet that the Mormons did not desire war, and "if we can keep the peace for this winter, I do think there will be something turned up that may save the shedding of blood". However, marking a change from earlier pronouncements, Young declared that under threat from an approaching army, he would not allow the new governor and federal officers to enter Utah. Nevertheless, Van Vliet told Young that he believed that the Mormons "have been lied about the worst of any people I ever saw". He promised to stop the Utah Expedition on his own authority, and on September 14, he returned east through the Mormon fortifications then being built in Echo Canyon (see below).

Upon returning to the main body of the army, Van Vliet reported that the Latter-day Saints would not resort to actual hostilities but would seek to delay the troops in every way possible. He also reported that they were ready to burn their homes and destroy their crops and that the route through Echo Canyon would be a death trap for a large body of troops. Van Vliet continued on to Washington, D.C., in company with Dr. John M. Bernhisel, Utah Territory's delegate to Congress. There, Van Vliet reported on the situation in the west and became an advocate for the Latter-day Saints and the end of the Utah War.

Martial law

As early as August 5, Young had decided to declaremartial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

throughout the Territory, and a document was printed to that effect. However, historians question the intent of this proclamation as it was never widely circulated, if at all, and while copies of the document exist, there is no mention of it in any contemporary sources. One commentary opines that "during most of August, the Mormon leaders had not precisely focused on a strategy for dealing with the approaching army; and after the first proclamation was struck off, they likely had second thoughts about a direct confrontation with the federal government. On August 29, Brigham Young instructed Daniel H. Wells to draft a second proclamation of martial law."

On September 15, the day after Van Vliet left Salt Lake City, Young publicly declared martial law in Utah with a document almost identical to that printed in early August. This second proclamation received wide circulation throughout the Territory and was delivered by messenger to Col. Alexander with the approaching army. The most important provision forbade "all armed forces of every description from coming into this Territory, under any pretense whatsoever". It also commanded that "all the forces in said Territory hold themselves in readiness to march at a moment's notice to repel any and all such invasion." But more important to California and Oregon bound travelers was the third section that stated "Martial law is hereby declared to exist in this Territory ... and no person shall be allowed to pass or repass into, through or from this territory without a permit from the proper officer."

Contact

The Nauvoo Legion finally made contact with federal troops in late September just west of South Pass. The militia immediately began to burn grass along the trail and stampede the army's cattle. In early October, Legion members burned downFort Bridger

Fort Bridger was originally a 19th-century fur trading outpost established in 1842, on Blacks Fork of the Green River, in what is now Uinta County, Wyoming, United States and was then part of Mexico. It became a vital resupply point for wagon ...

lest it falls into the hands of the army. A few days later, three large Army supply trains that were trailing the main army detachments were burned by Mormon cavalry led by Lot Smith

Lot Smith (May 15, 1830 – June 20, 1892) was a Mormon pioneer, soldier, lawman and American frontiersman. He became known as "The Horseman" for his exceptional skills on horseback as well as for his help in rounding up wild mustangs on Ut ...

. Associated horses and cattle were "liberated" from the supply trains and taken west by the militia. Few if any shots were fired in these exchanges, and the Army's lack of cavalry left them more or less open to Mormon raids. However, the army began to grow weary of the constant Mormon harassment throughout the fall. At one point, Colonel Alexander mounted roughly 100 men on army mules to combat the Mormon militia. In the early morning of 15 October, this "jackass cavalry" had a run-in with Lot Smith's command and fired over 30 bullets at the Mormons from 150 yards. No one was killed, but one Mormon took a bullet through his hat band, and one horse was grazed.

Through October and November, between 1,200 and 2,000 militiamen were stationed in Echo Canyon and Weber Canyon. These two narrow passes lead into the Salt Lake Valley, and provided the easiest access to the populated areas of northern Utah. Dealing with a heavy snowfall and intense cold, the Mormon men built fortifications, dug rifle pits and dammed streams and rivers in preparation for a possible battle either that fall or the following spring. Several thousand more militiamen prepared their families for evacuation and underwent military training.

On October 16, Major Joseph Taylor and his Adjutant William Stowell

William Stowell (March 13, 1885 – November 24, 1919) was an American silent film actor.

A handsome actor with matinee idol good looks, Stowell was signed into film in 1909 with the Independent Moving Pictures Company, better known si ...

of the Nauvoo Legion encountered a camp in the fog ahead of them. Supposing them to be the battalion of Lot Smith, they approached not realizing it was a detachment of US Army soldiers. They were captured and taken back to the main detachment where they were questioned by Col. Alexander. Taylor and Stowell gave exaggerated accounts of "twenty-five to thirty thousand" Mormon militia camped in Echo Canyon to repel the army if they were to pass through. The two men were held as prisoners at Camp Scott near Fort Bridger.

Colonel Alexander, whose troops referred to him as "old granny", opted not to enter Utah through Echo Canyon following Van Vliet's report, as well as news of the Mormon fortifications by Taylor and Stowell. Alexander instead maneuvered his troops around the Mormon defenses, entering Utah from the north along the Bear River before being forced to turn back upon running into a heavy blizzard in late October. Colonel Johnston took command of the combined U.S. forces in early November, by this time the command was hampered by a lack of supplies, animals, and the early onset of winter. Johnston was a more aggressive commander than Alexander but this predicament rendered him unable to immediately attack through Echo Canyon into Utah. Instead, he settled his troops into ill-equipped winter camps designated Camp Scott and Eckelsville, near the burned-out remains of Fort Bridger

Fort Bridger was originally a 19th-century fur trading outpost established in 1842, on Blacks Fork of the Green River, in what is now Uinta County, Wyoming, United States and was then part of Mexico. It became a vital resupply point for wagon ...

, now in the state of Wyoming. Johnston was soon joined by the 2nd Dragoons commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke

Philip St. George Cooke (June 13, 1809 – March 20, 1895) was a career United States Army cavalry officer who served as a Union General in the American Civil War. He is noted for his authorship of an Army cavalry manual, and is sometimes calle ...

, who had accompanied Alfred Cumming, Utah's new governor, and a roster of other federal officials from Fort Leavenworth. However, they too were critically short of horses and supplies.

In early November, Joseph Taylor of the Nauvoo Legion escaped captivity at Camp Scott and returned to Salt Lake City to report conditions of the army to Brigham Young. On 21 November, Cumming sent a proclamation to the citizens of Utah declaring them to be in rebellion. On November 26, 1857, Brigham Young wrote letter to Colonel Johnston at Fort Bridger inquiring of the prisoners and stating of William "....if you imagine that keeping, mistreating or killing Mr. Stowell will resound to your advantage, future experience may add to the stock of your better judgment."

At Eckelsville, Chief Justice Eckels and Governor Cumming set up a temporary seat of territorial government. Eckels convened a grand jury on December 30, which indicted twenty Mormons for high treason, including Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball

Heber Chase Kimball (June 14, 1801 – June 22, 1868) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement. He served as one of the original twelve apostles in the early Church of the Latter Day Saints, and as first counselor to Brigham Young ...

, Daniel H. Wells, John Taylor

John Taylor, Johnny Taylor or similar is the name of:

Academics

*John Taylor (Oxford), Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, 1486–1487

* John Taylor (classical scholar) (1704–1766), English classical scholar

*John Taylor (English publisher) ...

, George D. Grant, Lot Smith, Orrin Porter Rockwell

Orrin Porter Rockwell (June 28, 1813 or June 25, 1815 – June 9, 1878) was a figure of the Wild West period of American history. A lawman in the Utah Territory, he was nicknamed ''Old Port'', ''The Destroying Angel of Mormondom'' and ''Modern-da ...

, William A. Hickman, Albert Carrington

Albert Carrington (January 8, 1813 – September 19, 1889) was an apostle and member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).

Early life

Carrington was born i ...

, Joseph Taylor, Robert Burton, James Ferguson, Ephraim Hanks

Ephraim Knowlton Hanks (21 March 1826 – 9 June 1896) was a prominent member of the 19th-Century Latter Day Saint movement, a Mormon pioneer and a well known leader in the early settlement of Utah.

Hanks was born in Madison, Lake County, Ohio, th ...

, and William Stowell

William Stowell (March 13, 1885 – November 24, 1919) was an American silent film actor.

A handsome actor with matinee idol good looks, Stowell was signed into film in 1909 with the Independent Moving Pictures Company, better known si ...

, among others. On January 5, 1858, Justice Eckels held a court proceeding where William Stowell was arraigned in person on behalf of all of the defendants on charges of high treason. Stowell pled not guilty and requested more time to prepare for trial. Johnston awaited resupply and reinforcement and prepared to attack the Mormon positions after the spring thaw.

December 1857 – March 1858: winter intermission

Soldiers advance up the Colorado River

During this winter season, Lt.Joseph Christmas Ives

Joseph Christmas Ives (25 December 1829 – 12 November 1868) was an American soldier, botanist, and an explorer of the Colorado River in 1858.

Biography

Ives was born in New York City on Christmas Day, 1829. He graduated from Bowdoin College ...

was embarking on an assigned task of exploring and surveying the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

by steamship to determine the extent of the river's navigability. While steaming upstream in the Explorer from the Colorado River Delta

The Colorado River Delta is the region where the Colorado River once flowed into the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez) in eastern Mexicali Municipality in the north of the state of Baja California, in northwestern Mexico. The ...

toward Fort Yuma

Fort Yuma was a fort in California located in Imperial County, across the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona. It was established in 1848. It served as a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route from 1858 until 1861. The fort was retired from ...

in early January 1858, Ives received two hastily written dispatches from his commanding officer informing him of the outbreak of the Mormon War. These letters reported that Mormons were already engaged in hostilities with United States Army forces who were attempting to enter Utah from the east, and Ives's expedition took on a new meaning. The War Department was now considering launching a second front in Utah via the Colorado. Ives, who had anticipated a leisurely ascent of the river, was instructed to disregard his original orders. He was now ordered to ascend the Colorado to the head of navigation with utmost speed to determine the feasibility of transporting troops and war material up the Colorado by steamer to the mouth of the Virgin River

The Virgin River is a tributary of the Colorado River in the U.S. states of Utah, Nevada, and Arizona. The river is about long.Calculated with Google Maps and Google Earth It was designated Utah's first wild and scenic river in 2009, during the ...

, and thence overland to Utah. It was also rumored in Washington that Mormons might try to retreat down the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

and into Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

. An army advancing up the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

would cut off this escape route. Ives was instructed to proceed with extreme caution, since treacherous Mormons might already be lurking on the Colorado above Yuma.

Meanwhile, George Alonzo Johnson

George Alonzo Johnson (August 16. 1824 – November 27, 1903) was an American entrepreneur and politician.

Biography

Early life

Johnson was born in Palatine Bridge, New York, to Gertrydt van Slyk (1794–1826) and George Granville Johnson ( ...

, a merchant who had an established business transporting goods by steamship between the Colorado River Delta

The Colorado River Delta is the region where the Colorado River once flowed into the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez) in eastern Mexicali Municipality in the north of the state of Baja California, in northwestern Mexico. The ...

and Fort Yuma

Fort Yuma was a fort in California located in Imperial County, across the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona. It was established in 1848. It served as a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route from 1858 until 1861. The fort was retired from ...

, was upset that he had not been awarded command of the expedition's original exploratory mission. When Ives was chosen instead, he used the rumors of Indian unrest and purported Mormon designs on the Colorado river and successfully organized a second armed expedition in competition with Ives. He obtained an escort of soldiers commanded by Lt. James A. White from Fort Yuma's acting commander, Lt. A. A. Winder. On December 31, 1857, several days before Ives's arrival at Fort Yuma, Johnson's party steamed upstream from Yuma aboard the steamer ''General Jesup''.

Ives arrived at Yuma on the evening of January 5, 1858. Reacting to Johnson's departure and urgent dispatches from Washington, Ives had taken an overland shortcut on horseback in order to reorganize his command prior to the steamer's arrival and to facilitate a rapid ascent to the Virgin River

The Virgin River is a tributary of the Colorado River in the U.S. states of Utah, Nevada, and Arizona. The river is about long.Calculated with Google Maps and Google Earth It was designated Utah's first wild and scenic river in 2009, during the ...

as commanded. Ives' party steamed up the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

with frequent contact with Mojaves and other natives who traded with them and were allowed to board their vessel. Determining that they could not ascend the river beyond Black Canyon they turned back downstream. During their descent, the Mojave informed Ives that Mormons had recently been among the Mojaves and were inciting unrest by intimating that the real purpose of the river expedition was to steal Indian lands.

Upon hearing of Ives's steamer on the Colorado, Mormons feared that Ives might be bringing an army to Utah from the South. Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Hamblin (April 2, 1819 – August 31, 1886) was a Western pioneer, a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a diplomat to various Native American tribes of the Southwest and Great Basin. He a ...

, famed Mormon missionary of the Southwest, whose activities including establishing and maintaining Mormon–Indian alliances along the Colorado, set out in March with three other companions from Las Vegas to learn more about Ives's intentions. From excited Indians they learned of the approach of an "army" marching overland from Yuma – which in reality was Ives's packtrain.

Hamblin's group made direct contact with Ives expedition by sending Thaïes Haskell, to hail the steamer's crew from the bank while the other Mormons remained in hiding. He was to pass himself off as a renegade from Utah and then learn as much as possible about Ives's intentions; however, his guise failed since one of Ives's men who had been to Utah claimed to recognize him as a Mormon bishop.

The journals of members of the Ives expedition as well as the Mormons from Hamblin's group attest to the tension and war hysteria among both the US Army and the Mormons in these remote territories.

Thomas L. Kane

The lull in hostilities during the winter provided an opportunity for negotiations, and direct confrontation was avoided. As early as August 1857, Brigham Young had written to Thomas L. Kane of Pennsylvania asking for help. Kane was a man of some political prominence who had been helpful to the Mormons in their westward migration and later political controversies. In December, Kane contacted President Buchanan and offered to mediate between the Mormons and the federal government. In Buchanan'sState of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a Joint session of the United States Congress, joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning ...

address earlier in the month, he had taken a hard stand against the Mormon rebellion, and had actually asked Congress to enlarge the size of the regular army to deal with the crisis. However, in his conversation with Kane, Buchanan worried that the Mormons might destroy Johnston's Army at severe political cost to himself, and stated that he would pardon the Latter-day Saints for their actions if they would submit to government authority. He therefore granted Kane unofficial permission to attempt mediation, although he held little hope for the success of negotiations. Upon approval of his mission by the President, Kane immediately started for Utah. During the heavy winter of 1857–1858, he traveled under the alias "Dr. Osborne" over 3,000 miles from the East coast to Utah, first by ship to Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, crossing the isthmus via the newly constructed (1855) Panama Railway

The Panama Canal Railway (PCR, ) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches across the Isthmus of Panama from Colón (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near Panama City). Because of ...

, and then taking a second ship to San Francisco. Upon learning that the Sierra passes were blocked for the winter, he immediately took a ship to San Pedro, the unimproved harbor for what is now Los Angeles. He was met there by Mormons who took him overland through San Bernardino and Las Vegas, to Salt Lake City on the strenuous southern branch of the California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

, arriving in February 1858.

When Kane arrived in February 1858, Mormons referred to him as "the man the Lord had raised up as a peacemaker". Details of the negotiations between Kane and Young are unclear. It seems that Kane successfully convinced Young to accept Buchanan's appointment of Cumming as Territorial governor, although Young had expressed his willingness to accept such terms at the very beginning of the crisis. It is uncertain if Kane was able to convince Young at this time to allow the army into Utah. After his meeting with Brigham Young, Kane traveled to Camp Scott arriving on March 10, 1858. After deliberations, Governor Cumming and a small non-military escort which included Thomas Kane, left Camp Scott on April 5 and traveled to Salt Lake to formally install the new Governor. Governor Cumming was welcomed to Utah by "its most distinguished citizens" on April 12, 1858 and was shortly installed in his new office. Three days later, word was sent to Colonel Johnston that the Governor had been properly received by the people and was able to fully discharge his duties as Governor.

After spending some time in Salt Lake City, Governor Cumming made the return trip back to Eckelsville, departing Salt Lake on May 16. He met with military commanders and new authorities to make plans to travel into the valley. At the end of May, Major Benjamin McCulloch

Brigadier-General Benjamin McCulloch (November 11, 1811 – March 7, 1862) was a soldier in the Texas Revolution, a Texas Ranger, a major-general in the Texas militia and thereafter a major in the United States Army (United States Volunteers) ...

of Texas and Kentucky senator-elect Lazarus W. Powell arrived at Camp Scott as peace commissioners with a proclamation of general pardon from President Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvania in both houses of the U.S. Con ...

for previous indictments handed down to Mormon leaders. As the Governor and his military escort descended Echo Canyon to Salt Lake city, many of the Mormon militia men including now released prisoner William Stowell

William Stowell (March 13, 1885 – November 24, 1919) was an American silent film actor.

A handsome actor with matinee idol good looks, Stowell was signed into film in 1909 with the Independent Moving Pictures Company, better known si ...

, successfully fooled Cumming as to the size of the armed contingent lining the canyon. Mormon militia men marched in front of camp fires in circles at night to make it appear there were many shadows. When Cumming approached an encampment, the heavy set Governor lumbered over to speak to the saluting men telling them the conflict was over and they could return to their families. After each meeting, Cumming would travel with his escort to the next encampment down Echo Canyon to give the same address, not realizing many of the men had run through the dark ahead of the Governor with a small change of costume from the last encampment, making their numbers appear much larger than they were. Many of the Mormon militia men heard the Governor speech multiple times without being detected by Cumming.

The new Governor was courteously received by Young and the Utah citizenry in the first week of June 1858. Cumming thereafter became a moderate voice, and opposed the hardline against the Mormons proposed by Colonel Johnston and other federal officials traveling with the army to be installed in the territory. Kane left Utah for Washington, D.C. in May to report to President Buchanan on the results of his mission.

April–July 1858: resolution

Move south

Despite Thomas Kane's successful mission, tension continued throughout the spring and summer of 1858. Young was willing to support Cumming as governor, but he still feared persecution and violence if the army entered Utah. Indeed, as the snows melted, approximately 3,000 additional U.S. Army reinforcements set out on the westward trails to resupply and strengthen the Army's presence. In Utah, the Nauvoo Legion was bolstered as Mormon communities were asked to supply and equip an additional thousand volunteers to be placed in the over one hundred miles of mountains that separated Camp Scott and Great Salt Lake City. Nevertheless, by the end of the winter Young had decided to enforce his "Sevastopol Policy", a plan to evacuate the Territory and burn it to the ground rather than fight the army openly. Members of theHudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

and the British government feared that the Mormons planned to seek refuge on Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

off the coast of British Columbia.

David Bigler has shown that Young originally intended this evacuation to go northwards toward the Bitterroot Valley

The Bitterroot Valley is located in southwestern Montana, along the Bitterroot River between the Bitterroot Range and Sapphire Mountains, in the Northwestern United States.

Geography

The valley extends approximately from Lost Trail Pass in I ...

in present-day Montana. He believed conditions there were sufficient for the Mormons to live, but difficult enough that others would be discouraged from following them or settling there. However, the Bannock

Bannock may mean:

* Bannock (British and Irish food), a kind of bread, cooked on a stone or griddle served mainly in Scotland but consumed throughout the British Isles

* Bannock (Indigenous American food), various types of bread, usually prepare ...

and Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ), also known by the endonym Newe, are an Native Americans in the United States, Indigenous people of the United States with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshon ...

raid against Fort Limhi in February 1858 blocked this northern retreat. Consequently, at the end of March 1858, settlers in the northern counties of Utah including Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

boarded up their homes and farms and began to move south, leaving small groups of men and boys behind to burn the settlements if necessary. As early as February 1858, Young had sent parties to explore the White Mountains on what is now the Utah/Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

border where he, erroneously, believed there were valleys that could comfortably harbor up to 100,000 individuals. Residents of Utah County just south of Salt Lake were asked to build and maintain roads and to help the incoming inhabitants of the northern communities. Mormon Elias Blackburn recorded in his journal, "The roads are crowded with the Saints moving south. ... Very busy dealing out provisions to the public hands. I am feeding 100 men, all hard at work." Even after Alfred Cumming was installed as governor in mid-April, the "Move South" continued unabated. The movement may have included the relocation of nearly 30,000 people between March and July. Historians Allen and Leonard write:

Utah War Peace Commission

In the meantime, President Buchanan had come under considerable pressure from Congress to end the crisis. In February 1858, SenatorSam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

of Texas stated that a war against the Mormons would be

On April 1, Senator Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Ameri ...

of Pennsylvania declared that he would support a bill to authorize volunteers to fight in Utah and other parts of the frontier only because