Jesus College, Oxford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jesus College (in full: Jesus College in the University of Oxford of Queen Elizabeth's Foundation) is one of the constituent colleges of the

Jesus College was founded on 27 June 1571, when

Jesus College was founded on 27 June 1571, when  Price continued to be closely involved with the college after its foundation. On the strength of a promised legacy, worth £60 a year on his death (approximately £ in present-day terms), he requested and received the authority to appoint the new college's principal, fellows and scholars. He financed early building work in the college's front quadrangle, but on his death in 1574 it transpired that the college received only a

Price continued to be closely involved with the college after its foundation. On the strength of a promised legacy, worth £60 a year on his death (approximately £ in present-day terms), he requested and received the authority to appoint the new college's principal, fellows and scholars. He financed early building work in the college's front quadrangle, but on his death in 1574 it transpired that the college received only a

The main benefactor, other than the King, was Eubule Thelwall, from Ruthin, North Wales, who became Principal in 1621; he succeeded in securing a new charter and statutes for the college from James I, having spent £5,000 of his own money on the hall and chapel, which earned him the title of its second founder. Thelwall died on 8 October 1630, aged 68 and was buried in Jesus College Chapel where a monument was erected to his memory by his brother Sir Bevis Thelwall (Page of the King's Bedchamber and Clerk of the Great Wardrobe).

Other benefactions in the 17th century include Herbert Westfaling, the Bishop of Hereford, who left enough property to support two fellowships and scholarships (with the significant proviso that "my kindred shallbe always preferred before anie others"). Sir Eubule Thelwall (principal 1621–1630) spent much of his own money on the construction of a chapel, hall and library for the college. The library, constructed above an over-weak

The main benefactor, other than the King, was Eubule Thelwall, from Ruthin, North Wales, who became Principal in 1621; he succeeded in securing a new charter and statutes for the college from James I, having spent £5,000 of his own money on the hall and chapel, which earned him the title of its second founder. Thelwall died on 8 October 1630, aged 68 and was buried in Jesus College Chapel where a monument was erected to his memory by his brother Sir Bevis Thelwall (Page of the King's Bedchamber and Clerk of the Great Wardrobe).

Other benefactions in the 17th century include Herbert Westfaling, the Bishop of Hereford, who left enough property to support two fellowships and scholarships (with the significant proviso that "my kindred shallbe always preferred before anie others"). Sir Eubule Thelwall (principal 1621–1630) spent much of his own money on the construction of a chapel, hall and library for the college. The library, constructed above an over-weak

A

A

In the inter-war years (1918–1939) Jesus was seen by some as a small college and something of a backwater; it attracted relatively few pupils from the public schools traditionally seen as the most prestigious. The college did, however, attract many academically able entrants from the grammar schools (particularly those in

In the inter-war years (1918–1939) Jesus was seen by some as a small college and something of a backwater; it attracted relatively few pupils from the public schools traditionally seen as the most prestigious. The college did, however, attract many academically able entrants from the grammar schools (particularly those in

The chapel was dedicated on 28 May 1621, and extended in 1636.Baker (1954), p. 272 The architectural historian Giles Worsley has described the chapel's east window (added in 1636) as an instance of

The chapel was dedicated on 28 May 1621, and extended in 1636.Baker (1954), p. 272 The architectural historian Giles Worsley has described the chapel's east window (added in 1636) as an instance of  The principal of the college resides in the lodgings, a Grade I listed building, on the north side of the first quadrangle between the chapel (to the east) and the hall (to the west). They were the last part of the first quadrangle to be built.Hardy, p. 39 Sir Eubule Thelwall, principal from 1621 to 1630, built the lodgings at his own expense, to include (in the words of the antiquarian Anthony Wood) "a very fair dining-room adorned with wainscot curiously engraven". The shell-hood over the doorway (which Pevsner called "beautiful") was added at some point between 1670 and 1740; Pevsner dates it to about 1700.

The principal of the college resides in the lodgings, a Grade I listed building, on the north side of the first quadrangle between the chapel (to the east) and the hall (to the west). They were the last part of the first quadrangle to be built.Hardy, p. 39 Sir Eubule Thelwall, principal from 1621 to 1630, built the lodgings at his own expense, to include (in the words of the antiquarian Anthony Wood) "a very fair dining-room adorned with wainscot curiously engraven". The shell-hood over the doorway (which Pevsner called "beautiful") was added at some point between 1670 and 1740; Pevsner dates it to about 1700.

The hall has been said to be "among the most impressive of all the Oxford college halls", with its "fine panelling, austere ceiling, and its notable paintings". Like the chapel, it was largely built by Griffith Powell between 1613 and 1620, and was finally completed soon after his death in 1620. Pevsner noted the "elaborately decorated columns" of the screen (installed in 1634) and the dragons along the frieze, and said that it was one of the earliest examples in Oxford of panelling using four "L" shapes around a centre.Pevsner, p. 39 In 1741 and 1742, the oak-beamed roof was covered with plaster to make rooms in the roof space.Baker (1954), p. 275Hardy, p. 173 Pevsner described the 1741 cartouche on the north wall, which contains the college crest, as "large ndrich". The hall contains a portrait of Elizabeth I, as well as portraits of former principals and benefactors. There are also portraits by court artists of two other monarchs who were college benefactors: Charles I (by

The hall has been said to be "among the most impressive of all the Oxford college halls", with its "fine panelling, austere ceiling, and its notable paintings". Like the chapel, it was largely built by Griffith Powell between 1613 and 1620, and was finally completed soon after his death in 1620. Pevsner noted the "elaborately decorated columns" of the screen (installed in 1634) and the dragons along the frieze, and said that it was one of the earliest examples in Oxford of panelling using four "L" shapes around a centre.Pevsner, p. 39 In 1741 and 1742, the oak-beamed roof was covered with plaster to make rooms in the roof space.Baker (1954), p. 275Hardy, p. 173 Pevsner described the 1741 cartouche on the north wall, which contains the college crest, as "large ndrich". The hall contains a portrait of Elizabeth I, as well as portraits of former principals and benefactors. There are also portraits by court artists of two other monarchs who were college benefactors: Charles I (by

In 1640, Francis Mansell (appointed principal in 1630) began construction of a second quadrangle with buildings along the north and south sides; further work was interrupted by the

In 1640, Francis Mansell (appointed principal in 1630) began construction of a second quadrangle with buildings along the north and south sides; further work was interrupted by the

The long but narrow third quadrangle adjoins Ship Street, on the north of the site and to the west of the garden of the principal's lodgings, where the college has owned some land since its foundation. In the 18th century, this was home to the college stables. A fire in 1904 led to the demolition of the stables and the gateway to Ship Street. Replacement buildings adjoining Ship Street, effectively creating a third quadrangle for the college, were constructed between 1906 and 1908.Baker (1954), p. 277 It contained the college's science laboratories (now closed) and a new gate-tower, as well as further living accommodation and a library for students, known as the Meyricke Library, after a major donor – there had been an undergraduate library in the second quadrangle since 1865, known as the Meyricke Library from 1882 onwards.

The Old Members' Building, which contains a music room, 24 study-bedrooms and some lecture rooms, was built between 1969 and 1971. It was built after a fundraising appeal to Old Members to mark the college's quatercentenary, and was opened by the

The long but narrow third quadrangle adjoins Ship Street, on the north of the site and to the west of the garden of the principal's lodgings, where the college has owned some land since its foundation. In the 18th century, this was home to the college stables. A fire in 1904 led to the demolition of the stables and the gateway to Ship Street. Replacement buildings adjoining Ship Street, effectively creating a third quadrangle for the college, were constructed between 1906 and 1908.Baker (1954), p. 277 It contained the college's science laboratories (now closed) and a new gate-tower, as well as further living accommodation and a library for students, known as the Meyricke Library, after a major donor – there had been an undergraduate library in the second quadrangle since 1865, known as the Meyricke Library from 1882 onwards.

The Old Members' Building, which contains a music room, 24 study-bedrooms and some lecture rooms, was built between 1969 and 1971. It was built after a fundraising appeal to Old Members to mark the college's quatercentenary, and was opened by the

The Governing Body has the ability to elect "distinguished persons" to Honorary Fellowships.Statute IV "The Fellows", clause 23 "Honorary Fellowships" Under the current statutes of the college, Honorary Fellows cannot vote at meetings of the Governing Body and do not receive financial reward. They can be called upon, however, to help decide whether to dismiss or discipline members of academic staff (including the Principal).

Three former principals of the college ( John Christie, Sir John Habakkuk and Sir Peter North) have been elected Honorary Fellows on retirement. Some Honorary Fellows were formerly Fellows of the college, others were Old Members of the college, and some were in both categories. Others had no previous academic connection with the college before their election. Some of these were distinguished Welshmen – for example, the Welsh businessman Sir Alfred Jones was elected in 1902 and the Welsh judge Sir Samuel Evans, President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court, was elected in 1918. The Welsh politician

The Governing Body has the ability to elect "distinguished persons" to Honorary Fellowships.Statute IV "The Fellows", clause 23 "Honorary Fellowships" Under the current statutes of the college, Honorary Fellows cannot vote at meetings of the Governing Body and do not receive financial reward. They can be called upon, however, to help decide whether to dismiss or discipline members of academic staff (including the Principal).

Three former principals of the college ( John Christie, Sir John Habakkuk and Sir Peter North) have been elected Honorary Fellows on retirement. Some Honorary Fellows were formerly Fellows of the college, others were Old Members of the college, and some were in both categories. Others had no previous academic connection with the college before their election. Some of these were distinguished Welshmen – for example, the Welsh businessman Sir Alfred Jones was elected in 1902 and the Welsh judge Sir Samuel Evans, President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court, was elected in 1918. The Welsh politician

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

in England. It is in the centre of the city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

, on a site between Turl Street, Ship Street, Cornmarket Street and Market Street. The college was founded by Queen Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

on 27 June 1571. A major driving force behind the establishment of the college was Hugh Price (or Ap Rhys), a churchman from Brecon

Brecon (; ; ), archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701. The population in 2001 was 7,901, increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the county town of Breck ...

in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

. The oldest buildings, in the first quadrangle, date from the 16th and early 17th centuries; a second quadrangle was added between about 1640 and about 1713, and a third quadrangle was built in about 1906. Further accommodation was built on the main site to mark the 400th anniversary of the college, in 1971, and student flats have been constructed at sites in north and east Oxford. A fourth quadrangle was completed in 2021.

There are about 475 students at any one time; the Principal of the college is Sir Nigel Shadbolt. Former students include Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

(who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

), Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

(Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

), Norman Washington Manley ( Prime Minister of Jamaica), T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), Angus Buchanan (winner of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

), Viscount Sankey (Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

), Edwin Yoder (Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

winning journalist), Roger Parry (media and technology entrepreneur) and over 30 Members of Parliament. Past or present fellows of the college include the historians Sir Goronwy Edwards, Yuval Noah Harari and Niall Ferguson

Sir Niall Campbell Ferguson, ( ; born 18 April 1964)Biography

Niall Ferguson

, the philosopher Galen Strawson, and the political philosopher John Gray. Past students and fellows in the sciences include John Houghton (physicist) and Nobel Laureate Peter J. Ratcliffe.

Niall Ferguson

History

Foundation

Jesus College was founded on 27 June 1571, when

Jesus College was founded on 27 June 1571, when Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

issued a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

. It was the first Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

college to be founded at the university, and it is the only Oxford college to date from Elizabeth's reign. It was the first new Oxford college since 1555, in the reign of Queen Mary, when Trinity College and St John's College were founded as Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

colleges. The foundation charter named a principal ( David Lewis), eight fellows, eight scholars

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a terminal ...

, and eight commissioners to draw up the statutes for the college.Hardy, p. 13 The commissioners included Hugh Price, who had petitioned the queen to found a college at Oxford "that he might bestow his estate of the maintenance of certain scholars of Wales to be trained up in good letters." The charter also transferred to the college the land and buildings of White Hall, an academic hall on part of the current site. The college was originally intended primarily for the education of clergy. The particular intention was to satisfy a need for dedicated, learned clergy to promote the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Ref ...

in the parishes of England, Ireland and Wales. The college has since broadened the range of subjects offered, beginning with the inclusion of medicine and law, and now offers almost the full range of subjects taught at the university. The letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

issued by Elizabeth I made it clear that the education of a priest in the 16th century included more than just theology, however:Baker (1971), p. 1

Price continued to be closely involved with the college after its foundation. On the strength of a promised legacy, worth £60 a year on his death (approximately £ in present-day terms), he requested and received the authority to appoint the new college's principal, fellows and scholars. He financed early building work in the college's front quadrangle, but on his death in 1574 it transpired that the college received only a

Price continued to be closely involved with the college after its foundation. On the strength of a promised legacy, worth £60 a year on his death (approximately £ in present-day terms), he requested and received the authority to appoint the new college's principal, fellows and scholars. He financed early building work in the college's front quadrangle, but on his death in 1574 it transpired that the college received only a lump sum

A lump sum is a single payment of money, as opposed to a series of payments made over time (such as an annuity).

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development distinguishes between " price analysis" and " cost analysis" by whether ...

of around £600 (approximately £ in present-day terms). Problems with his bequest meant that it was not received in full for about 25 years. As the college had no other donors at this time, "for many years the college had buildings but no revenue".Baker (1954), p. 264

17th century

The main benefactor, other than the King, was Eubule Thelwall, from Ruthin, North Wales, who became Principal in 1621; he succeeded in securing a new charter and statutes for the college from James I, having spent £5,000 of his own money on the hall and chapel, which earned him the title of its second founder. Thelwall died on 8 October 1630, aged 68 and was buried in Jesus College Chapel where a monument was erected to his memory by his brother Sir Bevis Thelwall (Page of the King's Bedchamber and Clerk of the Great Wardrobe).

Other benefactions in the 17th century include Herbert Westfaling, the Bishop of Hereford, who left enough property to support two fellowships and scholarships (with the significant proviso that "my kindred shallbe always preferred before anie others"). Sir Eubule Thelwall (principal 1621–1630) spent much of his own money on the construction of a chapel, hall and library for the college. The library, constructed above an over-weak

The main benefactor, other than the King, was Eubule Thelwall, from Ruthin, North Wales, who became Principal in 1621; he succeeded in securing a new charter and statutes for the college from James I, having spent £5,000 of his own money on the hall and chapel, which earned him the title of its second founder. Thelwall died on 8 October 1630, aged 68 and was buried in Jesus College Chapel where a monument was erected to his memory by his brother Sir Bevis Thelwall (Page of the King's Bedchamber and Clerk of the Great Wardrobe).

Other benefactions in the 17th century include Herbert Westfaling, the Bishop of Hereford, who left enough property to support two fellowships and scholarships (with the significant proviso that "my kindred shallbe always preferred before anie others"). Sir Eubule Thelwall (principal 1621–1630) spent much of his own money on the construction of a chapel, hall and library for the college. The library, constructed above an over-weak colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

, was pulled down under the principalship of Francis Mansell (1630–1649), who also built two staircases of residential accommodation to attract the sons of Welsh gentry families to the college.

The English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

"all but destroyed the corporate life of the college."Baker (1954), p. 265. Mansell was removed from his position as principal and Michael Roberts was installed. After the Restoration, Mansell was briefly reinstated as principal, before resigning in favour of Leoline Jenkins.Baker (1954), p. 266 It was Jenkins (principal 1661–1673) who secured the long-term viability of the college. On his death, in 1685, he bequeathed a large complex of estates, acquired largely by lawyer friends from the over-mortgaged landowners of the Restoration period. These estates allowed the college's sixteen fellowships and scholarships to be filled for the first time – officially, sixteen of each had been supported since 1622, but the college's income was too small to keep all occupied simultaneously. In 1713, the bequest of Welsh clergyman and former student Edmund Meyricke established a number of scholarships for students from north Wales, although these are now available to all Welsh students.Baker (1954), p. 267

18th and 19th centuries

The 18th century, in contrast to the disruption of the 17th century, was a comparatively quiet time for the college. A historian of the college, J. N. L. Baker, wrote that the college records for this time "tell of little but routine entries and departures of fellows and scholars". TheNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

saw a reduction in the numbers of students and entries in the records for the purchase of musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually dis ...

s and other items for college members serving in the university corps. After the war, numbers rose, to an average of twenty new students per year between 1821 and 1830. However, debts owed to the college had increased, perhaps due to the economic effects of the war – by 1832, the college was owed £986 10s 5d (approximately £ in present-day terms).Baker (1954), p. 268 During the first half of the 19th century, the academic strength of the college diminished: scholarships were sometimes not awarded because of a lack of suitable candidates, and numbers fell: there were only seven new entrants in 1842. Ernest Hardy wrote in his history of the college in 1899 that it had been becoming "increasingly evident for years... that the exclusive connection with Wales was ruining the college as a place of education."

Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

was appointed in 1852 to investigate the university. The college wished to retain its links with Wales, and initial reforms were limited despite the wishes of the commissioners: those scholarships that were limited to particular parts of Wales were opened to the whole of Wales, and half of the fellowships awarded were to remain open only to Welshmen if and so long as the Principal and Fellows shall deem it expedient for the interests of education in connection with the Principality of Wales. All the scholarships at the college, except for two, and all the exhibitions were still restricted to students from Wales. The numbers of students at the college still fell, despite prizes being awarded for success in university examinations. Daniel Harper, principal from 1877 to 1895, noted the continuing academic decline. Speaking in 1879, he noted that fewer students from the college were reaching high standards in examinations, and that more Welsh students were choosing to study at other Oxford colleges in preference to Jesus. A further Royal Commission was appointed. This led to further changes at the college: in 1882, the fellowships reserved to Welshmen were made open to all, and only half (instead of all) of the 24 scholarships were to be reserved for Welsh candidates.Baker (1954), p. 269 Thereafter, numbers gradually rose and the non-Welsh element at the college increased, so that by 1914 only about half of the students were Welsh.

20th century

During theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, "the college in the ordinary sense almost ceased to exist". From 129 students in the summer of 1914, numbers dropped to 36 in the spring of 1916. Some refugee students from Belgium and Serbia lodged in empty rooms in the college during 1916, and officers of the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

resided from August 1916 to December 1918. After the war, numbers rose and fellowships were added in new subjects: history (1919 and 1933); theology (1927); physics (1934); a second fellowship in chemistry (1924); and modern languages (lectureship 1921, fellowship 1944). The improved teaching led to greater success in university examinations and prizes.Baker (1954), p. 270

In the inter-war years (1918–1939) Jesus was seen by some as a small college and something of a backwater; it attracted relatively few pupils from the public schools traditionally seen as the most prestigious. The college did, however, attract many academically able entrants from the grammar schools (particularly those in

In the inter-war years (1918–1939) Jesus was seen by some as a small college and something of a backwater; it attracted relatively few pupils from the public schools traditionally seen as the most prestigious. The college did, however, attract many academically able entrants from the grammar schools (particularly those in northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

and Scotland). Among these grammar-school boys was Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

, who would later become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

. During the Second World War, many of the fellows served in the armed forces or carried out war work in Oxford. The college remained full of students, though, as it provided lodgings for students from other colleges whose buildings had been requisitioned, and also housed officers on military courses.Baker (1954), p. 271

The college had its own science laboratories from 1907 to 1947, which were overseen (for all but the last three years) by the physical chemist David Chapman, a fellow of the college from 1907 to 1944. At the time of their closure, they were the last college-based science laboratories at the university. They were named the Sir Leoline Jenkins laboratories, after a former principal of the college. The laboratories led to scientific research and tuition (particularly in chemistry) becoming an important part of the college's academic life. The brochure produced for the opening ceremony noted that the number of science students at the college had increased rapidly in recent years, and that provision of college laboratories would assist the tuition of undergraduates, as well as attracting to Jesus College graduates of the University of Wales

The University of Wales () is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff – the university was the first universit ...

who wished to continue their research at Oxford. A link between one of the college science lecturers and Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British Chemical industry, chemical company. It was, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain. Its headquarters were at Millbank in London. ICI was listed on the London Stock Exchange ...

(ICI) led to 17 students joining ICI between the two World Wars, some, such as John Rose, reaching senior levels in the company. The laboratories became unnecessary when the university began to provide centralised facilities for students; they were closed in 1947.

The quatercentenary of the college, in 1971, saw the opening of the Old Members' Buildings in the third quadrangle. Further student accommodation has been built at the sports ground and at a site in north Oxford. In 1974, Jesus was among the first group of five men's colleges to admit women as members, the others being Brasenose, Wadham, Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a Ford (crossing), ford on ...

and St Catherine's; between one-third and one-half of the undergraduates are women. A long-standing rivalry

A rivalry is the state of two people or groups engaging in a lasting competitive relationship. Rivalry is the "against each other" spirit between two competing sides. The relationship itself may also be called "a rivalry", and each participant ...

with nearby Exeter College reached a peak in 1979, with seven police vehicles and three fire engines involved in dealing with trouble in Turl Street. Sir John Habakkuk (principal 1967–1984) and Sir Peter North (principal 1984–2005) both served terms as Vice-Chancellor of the university, from 1973 to 1977 and from 1993 to 1997 respectively.

21st century

The hereditaryvisitor

A visitor, in English and Welsh law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution, often a charitable institution set up for the perpetual distribution of the founder's alms and bounty, who can interve ...

of the college remains the Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by r ...

''. The current visitor is William Herbert, 18th Earl of Pembroke, 15th Earl of Montgomery. Jesus, Magdalene College, Cambridge and Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge

Sidney Sussex College (historically known as "Sussex College" and today referred to informally as "Sidney") is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England. The College was founded in 1 ...

are the only three Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford, Universities of Oxford and University of Cambridge, Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most prestigious universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collect ...

colleges that continue to prescribe by statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

visitations held by hereditary peers

The hereditary peers form part of the peerage in the United Kingdom. As of April 2025, there are 800 hereditary peers: 30 dukes (including six royal dukes), 34 marquesses, 189 earls, 108 viscounts, and 439 barons (not counting subsidiary ...

.

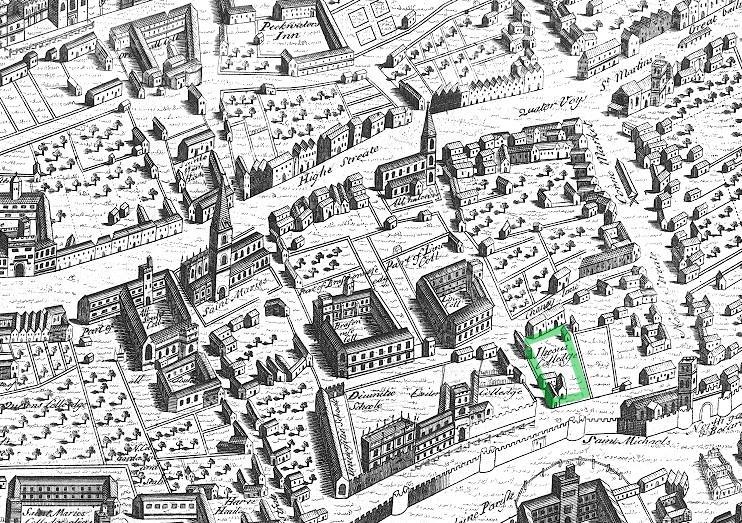

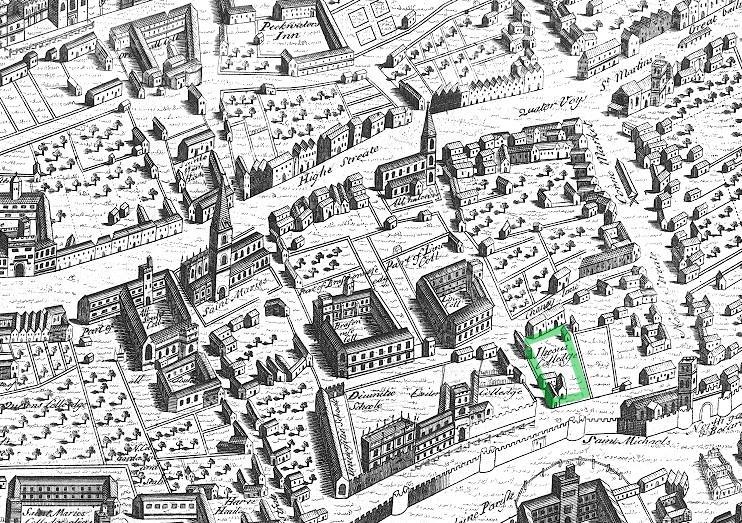

Location and buildings

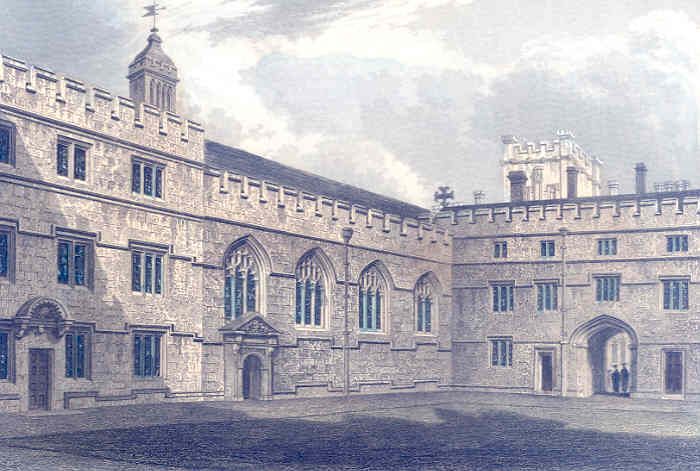

The main buildings are located in the centre of Oxford, between Turl Street, Ship Street, Cornmarket Street and Market Street. The main entrance is on Turl Street. The buildings are arranged in three quadrangles, the first quadrangle containing the oldest college buildings and the third quadrangle the newest. The foundation charter gave to the college a site between Market Street and Ship Street (which is still occupied by the college) as well as the buildings of a defunct university academic hall on the site, called White Hall.Hardy, p. 9 The buildings that now surround the first quadrangle were erected in stages between 1571 and the 1620s; the principal's lodgings were the last to be built. Progress was slow because the new college lacked the "generous endowments" that earlier colleges enjoyed. Before new buildings were completed, the students lived in the old buildings of White Hall.Hardy, p. 17First quadrangle

The chapel was dedicated on 28 May 1621, and extended in 1636.Baker (1954), p. 272 The architectural historian Giles Worsley has described the chapel's east window (added in 1636) as an instance of

The chapel was dedicated on 28 May 1621, and extended in 1636.Baker (1954), p. 272 The architectural historian Giles Worsley has described the chapel's east window (added in 1636) as an instance of Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

architecture, rather than Gothic Survival, since a choice was made to use an outdated style – classical architecture

Classical architecture typically refers to architecture consciously derived from the principles of Ancient Greek architecture, Greek and Ancient Roman architecture, Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or more specifically, from ''De archit ...

had become accepted as "the only style in which it was respectable to build". Jonathan Edwards (principal from 1686 to 1712) is reported to have spent £1,000 (approximately £ in present-day terms) during his lifetime on the interior of the chapel, including the addition of a screen separating the main part of the chapel from the ante-chapel (at the west end) in 1693. In 1853, stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

by George Hedgeland was added to the east window.Baker (1954), p. 276 In 1863, the architect George Edmund Street

George Edmund Street (20 June 1824 – 18 December 1881), also known as G. E. Street, was an English architect, born at Woodford in Essex. Stylistically, Street was a leading practitioner of the Victorian Gothic Revival. Though mainly an eccl ...

was appointed to renovate the chapel. The arch of the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

was widened, the original Jacobean woodwork was removed (save for the screen donated by Edwards and the pulpit), new seats were installed, new paving was placed in the main part of the chapel and a stone reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a Church (building), church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular a ...

was added behind the altar.Baker (1954), p. 276Hardy, p. 233 Views of the changes have differed. On 21 October 1864, ''Building News'' reported that the restoration was nearing completion and was of "a very spirited character". It said that the new "handsome" arch showed the east window "to great advantage", with "other improvements" including a "handsome reredos". Ernest Hardy, principal from 1921 to 1925, said that the work was "ill-considered", described the reredos as "somewhat tawdry" and said that the Jacobean woodwork had been sold off too cheaply.Hardy, p. x In contrast, the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (195 ...

called the reredos "heavily gorgeous".Pevsner, p. 143

The principal of the college resides in the lodgings, a Grade I listed building, on the north side of the first quadrangle between the chapel (to the east) and the hall (to the west). They were the last part of the first quadrangle to be built.Hardy, p. 39 Sir Eubule Thelwall, principal from 1621 to 1630, built the lodgings at his own expense, to include (in the words of the antiquarian Anthony Wood) "a very fair dining-room adorned with wainscot curiously engraven". The shell-hood over the doorway (which Pevsner called "beautiful") was added at some point between 1670 and 1740; Pevsner dates it to about 1700.

The principal of the college resides in the lodgings, a Grade I listed building, on the north side of the first quadrangle between the chapel (to the east) and the hall (to the west). They were the last part of the first quadrangle to be built.Hardy, p. 39 Sir Eubule Thelwall, principal from 1621 to 1630, built the lodgings at his own expense, to include (in the words of the antiquarian Anthony Wood) "a very fair dining-room adorned with wainscot curiously engraven". The shell-hood over the doorway (which Pevsner called "beautiful") was added at some point between 1670 and 1740; Pevsner dates it to about 1700.

The hall has been said to be "among the most impressive of all the Oxford college halls", with its "fine panelling, austere ceiling, and its notable paintings". Like the chapel, it was largely built by Griffith Powell between 1613 and 1620, and was finally completed soon after his death in 1620. Pevsner noted the "elaborately decorated columns" of the screen (installed in 1634) and the dragons along the frieze, and said that it was one of the earliest examples in Oxford of panelling using four "L" shapes around a centre.Pevsner, p. 39 In 1741 and 1742, the oak-beamed roof was covered with plaster to make rooms in the roof space.Baker (1954), p. 275Hardy, p. 173 Pevsner described the 1741 cartouche on the north wall, which contains the college crest, as "large ndrich". The hall contains a portrait of Elizabeth I, as well as portraits of former principals and benefactors. There are also portraits by court artists of two other monarchs who were college benefactors: Charles I (by

The hall has been said to be "among the most impressive of all the Oxford college halls", with its "fine panelling, austere ceiling, and its notable paintings". Like the chapel, it was largely built by Griffith Powell between 1613 and 1620, and was finally completed soon after his death in 1620. Pevsner noted the "elaborately decorated columns" of the screen (installed in 1634) and the dragons along the frieze, and said that it was one of the earliest examples in Oxford of panelling using four "L" shapes around a centre.Pevsner, p. 39 In 1741 and 1742, the oak-beamed roof was covered with plaster to make rooms in the roof space.Baker (1954), p. 275Hardy, p. 173 Pevsner described the 1741 cartouche on the north wall, which contains the college crest, as "large ndrich". The hall contains a portrait of Elizabeth I, as well as portraits of former principals and benefactors. There are also portraits by court artists of two other monarchs who were college benefactors: Charles I (by Anthony van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (; ; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Flemish Baroque painting, Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Spanish Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh child of ...

) and Charles II (by Sir Peter Lely).Baker (1954), p. 278

Second quadrangle

In 1640, Francis Mansell (appointed principal in 1630) began construction of a second quadrangle with buildings along the north and south sides; further work was interrupted by the

In 1640, Francis Mansell (appointed principal in 1630) began construction of a second quadrangle with buildings along the north and south sides; further work was interrupted by the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

.Hardy, p. 91 Work began again in 1676, and the library (now the Fellows' Library) was completed by 1679.Hardy, p. 172Baker (1954), p. 274 Under Jonathan Edwards (principal from 1688 to 1712), further rooms were built to complete the quadrangle; the project was completed just after his death in 1712. Pevsner described the second quadrangle as "a uniform composition", noting the "regular fenestration by windows with round-arched lights, their hood-moulds forming a continuous frieze".Pevsner, p. 144 The Dutch gables have ogee

An ogee ( ) is an object, element, or curve—often seen in architecture and building trades—that has a serpentine- or extended S-shape (Sigmoid curve, sigmoid). Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combination of two semicircle, semicircula ...

sides and semi-circular pediments

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In ancient ...

. The writer Simon Jenkins said that the quadrangle has "the familiar Oxford Tudor windows and decorative Dutch gables, crowding the skyline like Welsh dragons' teeth and lightened by exuberant flower boxes".

The Fellows' Library contains bookcases decorated with strapwork dating from about 1628, which were used in an earlier library in the college. Hardy's opinion was that, "if only it had an open timber roof instead of the plain ceiling, it would be one of the most picturesque College Libraries". Another author said (in 1914, after the provision of a library for undergraduates elsewhere in the quadrangle) that it was "one of the most charming of Oxford libraries, and one of the least frequented". It holds 11,000 antiquarian printed books and houses many of the college's rare texts, including a Greek bible dating from 1545 and signed by Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, an intellectual leader of the ...

and others, much of the library of the scholar and philosopher Lord Herbert of Cherbury and 17th-century volumes by Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

and Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment that followed. His book (''Mathe ...

.

Third quadrangle

The long but narrow third quadrangle adjoins Ship Street, on the north of the site and to the west of the garden of the principal's lodgings, where the college has owned some land since its foundation. In the 18th century, this was home to the college stables. A fire in 1904 led to the demolition of the stables and the gateway to Ship Street. Replacement buildings adjoining Ship Street, effectively creating a third quadrangle for the college, were constructed between 1906 and 1908.Baker (1954), p. 277 It contained the college's science laboratories (now closed) and a new gate-tower, as well as further living accommodation and a library for students, known as the Meyricke Library, after a major donor – there had been an undergraduate library in the second quadrangle since 1865, known as the Meyricke Library from 1882 onwards.

The Old Members' Building, which contains a music room, 24 study-bedrooms and some lecture rooms, was built between 1969 and 1971. It was built after a fundraising appeal to Old Members to mark the college's quatercentenary, and was opened by the

The long but narrow third quadrangle adjoins Ship Street, on the north of the site and to the west of the garden of the principal's lodgings, where the college has owned some land since its foundation. In the 18th century, this was home to the college stables. A fire in 1904 led to the demolition of the stables and the gateway to Ship Street. Replacement buildings adjoining Ship Street, effectively creating a third quadrangle for the college, were constructed between 1906 and 1908.Baker (1954), p. 277 It contained the college's science laboratories (now closed) and a new gate-tower, as well as further living accommodation and a library for students, known as the Meyricke Library, after a major donor – there had been an undergraduate library in the second quadrangle since 1865, known as the Meyricke Library from 1882 onwards.

The Old Members' Building, which contains a music room, 24 study-bedrooms and some lecture rooms, was built between 1969 and 1971. It was built after a fundraising appeal to Old Members to mark the college's quatercentenary, and was opened by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

in 1971. The Fellows' Garden is between the Old Members' Building and the rear of the rooms on the west side of the second quadrangle. In 2002, a two-year project to rebuild the property above the college-owned shops on Ship Street was completed. As part of the work, the bottom floor was converted from rooms occupied by students and fellows into a new Junior Common Room (JCR), to replace the common room in the second quadrangle, which was by then too small to cope with the increased numbers of students.

Fourth quadrangle

In 2019, work began on redevelopment of a commercial property, Northgate House, owned by the college on the corner of Cornmarket and Market Streets, to provide new student accommodation above retail facilities with a new quad and other teaching facilities behind, projected for completion to mark the college's 450th anniversary in 2021. The new building is named the Cheng Yu-tung building after the late billionaire entrepreneur and philanthropist Cheng Yu-tung whose family provided the principal donation for the project.

Other buildings

The college purchased of land in east Oxford (near the Cowley Road) in 1903 for use as a sports ground. Residential accommodation was first built at the sports ground in 1967 (Thelwall House, rebuilt in 1998), with additions between 1988 and 1990 (Hugh Price House and Leoline Jenkins House). A further development, known as Hazel Court (after Alfred Hazel, principal 1925–1944), was built in 2000, bringing the total number of students who can be housed at the sports ground to 135. Donations from Edwin Stevens, an Old Member of the college, enabled the construction in 1974 of student flats at a site in north Oxford on the Woodstock Road, named "Stevens Close" in his honour. The college also owns a number of houses on Ship Street, which are used for student accommodation. It purchased a further site in Ship Street at a cost of £1.8M, which was converted at a projected cost of £5.5M to provide 31 student rooms with en-suite facilities, a 100-seat lecture theatre and other teaching rooms. The Ship Street Centre was officially opened by the Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Lord Patten of Barnes, on 25 September 2010.People associated with the college

Principals and Fellows

The college is run by the Principal andFellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

s. The Principal must be "a person distinguished for literary or scientific attainments, or for services in the work of education in the University or elsewhere". The Principal has "pre-eminence and authority over all members of the College and all persons connected therewith" and exercises "a general superintendence in all matters relating to education and discipline". The current Principal, Sir Nigel Shadbolt, was appointed in 2015. Fourteen Principals have been former students of the college: Griffith Powell (elected in 1613) was the first and Alfred Hazel (elected in 1925) was the most recent. The longest-serving principal was Henry Foulkes, from 1817 to 1857.

When the college was founded in 1571, the first charter installed David Lewis as Principal and named eight others as the first Fellows of the college. The statutes of 1622 allowed for 16 Fellows. There is now no limit on the number of Fellowships that the Governing Body can create. The college statutes provide for various categories of Fellows.Statute IV, clause 1 "Classes of Fellows and qualifications" Professorial Fellows are those Professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other tertiary education, post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin ...

s and Readers of the university who are allocated to the college by the university. One of these professorships is the Jesus Professor of Celtic, which is the only chair in Celtic Studies

Celtic studies or Celtology is the academic discipline occupied with the study of any sort of cultural output relating to the Celts, Celtic-speaking peoples (i.e. speakers of Celtic languages). This ranges from linguistics, literature and art h ...

at an English university. Celtic scholars such as Sir John Rhys and Ellis Evans have held the position since its creation in 1877. The chair is currently held by David Willis, who took up the position in 2020 after the previous holder Thomas Charles-Edwards retired in 2011. The zoologists Charles Godfray and Paul Harvey

Paul Harvey Aurandt (September 4, 1918 – February 28, 2009) was an American radio broadcaster for ABC News Radio. He broadcast ''News and Comment'' on mornings and mid-days on weekdays and at noon on Saturdays and also his famous ''The Rest o ...

are both Professorial Fellows. Official Fellows are those who hold tutorial or administrative appointments in the college. Past Official Fellows include the composer and musicologist John Caldwell, the historians Sir Goronwy Edwards and Niall Ferguson

Sir Niall Campbell Ferguson, ( ; born 18 April 1964)Biography

Niall Ferguson

, the philosopher Galen Strawson and the political philosopher John Gray. There are also Senior and Junior Research Fellows. Principals and Fellows who retire can be elected as Niall Ferguson

Emeritus

''Emeritus/Emerita'' () is an honorary title granted to someone who retires from a position of distinction, most commonly an academic faculty position, but is allowed to continue using the previous title, as in "professor emeritus".

In some c ...

Fellows.

A further category is that of Welsh Supernumerary Fellows, who are, in rotation, the Vice-Chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

s of Cardiff University

Cardiff University () is a public research university in Cardiff, Wales. It was established in 1883 as the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire and became a founding college of the University of Wales in 1893. It was renamed Unive ...

, Swansea University, Lampeter University, Aberystwyth University

Aberystwyth University () is a Public university, public Research university, research university in Aberystwyth, Wales. Aberystwyth was a founding member institution of the former federal University of Wales. The university has over 8,000 stude ...

, Bangor University and the University of Wales College of Medicine. There is one Welsh Supernumerary Fellow at a time, holding the position for not longer than three years. The first of these was John Viriamu Jones in 1897.Baker (1971), pp. 62–63

The college formerly had a category of missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

Fellows, known as Leoline Fellows after their founder, Leoline Jenkins (a former principal). In his will in 1685, he stated that "It is but too obvious that the persons in Holy Orders employed in his Majesty's fleet at sea and foreign plantations are too few." To address this, he established two Fellowships at Jesus College, whose holders should serve as clergy "in any of his Majesty's fleets or in his Majesty's plantations" under the direction of the Lord High Admiral and the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

respectively. The last of these, Frederick de Winton, was appointed in 1876 and held his Fellowship until his death in 1932. This category was abolished in 1877 by the Oxford and Cambridge Universities Commission, without prejudice to the rights of existing holders such as de Winton. Another category of Fellowship that was abolished in the 19th century was that of the King Charles I Fellows, founded by King Charles in 1636 and tenable by natives of the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

in an attempt by him to "reclaim the Channel Islands from the extreme Calvinism which characterised them."Hardy, p. 77 The first such Fellow was Daniel Brevint.

Honorary Fellows

The Governing Body has the ability to elect "distinguished persons" to Honorary Fellowships.Statute IV "The Fellows", clause 23 "Honorary Fellowships" Under the current statutes of the college, Honorary Fellows cannot vote at meetings of the Governing Body and do not receive financial reward. They can be called upon, however, to help decide whether to dismiss or discipline members of academic staff (including the Principal).

Three former principals of the college ( John Christie, Sir John Habakkuk and Sir Peter North) have been elected Honorary Fellows on retirement. Some Honorary Fellows were formerly Fellows of the college, others were Old Members of the college, and some were in both categories. Others had no previous academic connection with the college before their election. Some of these were distinguished Welshmen – for example, the Welsh businessman Sir Alfred Jones was elected in 1902 and the Welsh judge Sir Samuel Evans, President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court, was elected in 1918. The Welsh politician

The Governing Body has the ability to elect "distinguished persons" to Honorary Fellowships.Statute IV "The Fellows", clause 23 "Honorary Fellowships" Under the current statutes of the college, Honorary Fellows cannot vote at meetings of the Governing Body and do not receive financial reward. They can be called upon, however, to help decide whether to dismiss or discipline members of academic staff (including the Principal).

Three former principals of the college ( John Christie, Sir John Habakkuk and Sir Peter North) have been elected Honorary Fellows on retirement. Some Honorary Fellows were formerly Fellows of the college, others were Old Members of the college, and some were in both categories. Others had no previous academic connection with the college before their election. Some of these were distinguished Welshmen – for example, the Welsh businessman Sir Alfred Jones was elected in 1902 and the Welsh judge Sir Samuel Evans, President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court, was elected in 1918. The Welsh politician David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

was elected to an Honorary Fellowship in 1910 when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

. He wrote to Sir John Rhys, the Principal at the time, to thank the college for the honour, saying:

The first three Honorary Fellows, all former students of the college, were elected in October 1877: John Rhys, the first Jesus Professor of Celtic (later an Official Fellow (1881–1895) and Principal (1895–1915)); the historian John Richard Green; and the poet Lewis Morris

Lewis Morris (April 8, 1726 – January 22, 1798) was an American Founding Father, landowner, and developer from Morrisania, New York, presently part of Bronx County. He signed the U.S. Declaration of Independence as a delegate to the Conti ...

.Baker (1954) The college noted in 1998 that the number of Honorary Fellows of the college was markedly below the average of other Oxford colleges and it adopted a more methodical approach to increase numbers. Seven Honorary Fellows were elected that year, followed by another five in 1999. The college's Honorary Fellows have included two Old Members who later became Prime Minister of their respective countries: Norman Washington Manley, who studied at Jesus College as a Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international Postgraduate education, postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Esta ...

and who was Chief Minister of Jamaica from 1955 to 1962, and Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

, who was twice British Prime Minister (1964–1970 and 1974–1976). The first female honorary fellow was the journalist and broadcaster Francine Stock.

Alumni

Notable former students of the college have included politicians, scientists, writers, entertainers and academics. T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), known for his part in theArab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ), also known as the Great Arab Revolt ( ), was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Co ...

of 1916–1918 and for his writings including '' Seven Pillars of Wisdom'', studied history at the college. His thesis on Crusader castles (the fieldwork for which marked the beginning of his fascination with the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

) is held in the Fellows' Library. Other former students include Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx (11 March 1916 – 23 May 1995) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1964 to 1970 and again from 197 ...

, who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

from 1964 to 1970 and 1974–1976, Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

who was Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

, Norman Washington Manley who was Prime Minister of Jamaica, Pixley ka Isaka Seme (a founder and president of the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

), Sir William Williams ( Speaker of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

1680–1685), and Lord Sankey (Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

1929–1935). Members of Parliament from the three main political parties in the United Kingdom have attended the college, as have politicians from Australia (Neal Blewett

Neal Blewett, Order of Australia, AC (born 24 October 1933) is an Australian Australian Labor Party, Labor Party politician, diplomat and historian. He was the Australian House of Representatives, Member of the House of Representatives for Divis ...

), New Zealand ( Harold Rushworth), Sri Lanka ( Lalith Athulathmudali) and the United States ( Heather Wilson).

The founders' hopes that their college would produce prominent Welsh clergy were fulfilled in no small measure when a former student, A. G. Edwards, was elected the first Archbishop of Wales

The post of Archbishop of Wales () was created in 1920 when the Church in Wales was separated from the Church of England and disestablished. The four historic Welsh dioceses had previously formed part of the Province of Canterbury, and so came ...

when the Church in Wales

The Church in Wales () is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The position is currently held b ...

was disestablished in 1920. Two later Archbishops of Wales, Glyn Simon (Archbishop from 1968 to 1971) and Gwilym Owen Williams (Archbishop 1971–1982) were also educated at the college. Celticists associated with the college include Sir John Rhys, Sir John Morris-Jones, and Sir Thomas (T. H.) Parry-Williams, whilst the list of historians includes the college's first graduate, David Powel, who published the first printed history of Wales in 1584, the Victorian historian J. R. Green, and the historian Richard J. Evans. Angus Buchanan won the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

during the First World War. Record-breaking quadriplegic

Tetraplegia, also known as quadriplegia, is defined as the dysfunction or loss of Motor control, motor and/or Sense, sensory function in the Cervical vertebrae, cervical area of the spinal cord. A loss of motor function can present as either weak ...

solo sailor Hilary Lister was also a student here, whilst from the field of arts and entertainment there are names such as Elwyn Brook-Jones, actor, (1911–1962), Magnus Magnusson

Magnus Magnusson (born Magnús Sigursteinsson; 12 October 1929 – 7 January 2007) was an Icelandic-born British-based journalist, translator, writer and television presenter. Born in Reykjavík, he lived in Scotland for almost all his life, al ...

, presenter of ''Mastermind

Mastermind, Master Mind or The Mastermind may refer to:

Fictional characters

* Mastermind (Jason Wyngarde), a fictional supervillain in Marvel Comics, a title also held by his daughters:

** Martinique Jason, the first daughter and successor of the ...

'', the National Poet of Wales Gwyn Thomas, and television weather presenters Kirsty McCabe and Siân Lloyd. Nigel Hitchin, the Savilian Professor of Geometry

The position of Savilian Professor of Geometry was established at the University of Oxford in 1619. It was founded (at the same time as the Savilian Professor of Astronomy, Savilian Professorship of Astronomy) by Henry Savile (Bible translator), ...

at Oxford since 1997, studied at the college, as did Edward Hinds (a physicist who won the Rumford Medal in 2008), Chris Rapley (director of the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

), and the zoologists Edward Bagnall Poulton and James Brontë Gatenby.

Student life

There are about 325 undergraduates and 150 postgraduates. About half of the undergraduates studied at state schools before coming to Oxford, and about 10% are from overseas. Students from the college participate in a variety of extracurricular activities. Some contribute to student journalism for '' Cherwell'' or '' The Oxford Student''. The Turl Street Arts Festival (a week-long student-organised event) is held annually in conjunction with the two other colleges on Turl Street,Exeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

and Lincoln colleges. The festival, which takes place in Fifth Week of Hilary term

Hilary term is the second academic term of the University of Oxfordchoral scholarships, the chapel choir is well-attended by college members and others. The choir is non-auditioning for college members, and is run by one or more undergraduate organ scholars.

Every three years, the college co-organises the Somerville-Jesus Ball on the grounds of

In common with many Oxford colleges, Jesus provides sporting facilities for students, including playing fields at a site in east Oxford off the Cowley Road known as Bartlemas (for its proximity to St Bartholomew's Chapel). Football, rugby, netball, field hockey, cricket, and tennis can be played there. Squash courts are at a separate city-centre site on St Cross Road. The college also provides students with membership of the university's gym and swimming pool on Iffley Road.

Jesus College Boat Club (commonly abbreviated to JCBC) is the rowing club for members of the college. The club was formed in 1835, but rowing at the college predates the foundation of the club: a boat from the college was involved in the earliest recorded races between college crews at Oxford in 1815, when it competed against a crew from Brasenose College. These may have been the only two colleges who had boats racing at that time, and the Brasenose boat was usually victorious.Hardy, p. 229 Neither the men's nor the women's 1st VIIIs have been "Head of the River" during Eights Week, the main college races, but the women's 1st VIII was Head of the River in the spring races, Torpids, between 1980 and 1983. Jesus boats have also had other successful seasons: the 1896 Jesus College boat had a reputation of being one of the faster boats in the university,Hardy, p. 230 and the women's 1st VIII of 1993 won their "blades" in the first divisions of both Torpids and Eights Week, an achievement that led to the crew being described in the ''Jesus College Record'' as vying "not just for the College team of the decade, but perhaps for the team of the last three decades", in any sport.

A number of college members have rowed for the university against

In common with many Oxford colleges, Jesus provides sporting facilities for students, including playing fields at a site in east Oxford off the Cowley Road known as Bartlemas (for its proximity to St Bartholomew's Chapel). Football, rugby, netball, field hockey, cricket, and tennis can be played there. Squash courts are at a separate city-centre site on St Cross Road. The college also provides students with membership of the university's gym and swimming pool on Iffley Road.

Jesus College Boat Club (commonly abbreviated to JCBC) is the rowing club for members of the college. The club was formed in 1835, but rowing at the college predates the foundation of the club: a boat from the college was involved in the earliest recorded races between college crews at Oxford in 1815, when it competed against a crew from Brasenose College. These may have been the only two colleges who had boats racing at that time, and the Brasenose boat was usually victorious.Hardy, p. 229 Neither the men's nor the women's 1st VIIIs have been "Head of the River" during Eights Week, the main college races, but the women's 1st VIII was Head of the River in the spring races, Torpids, between 1980 and 1983. Jesus boats have also had other successful seasons: the 1896 Jesus College boat had a reputation of being one of the faster boats in the university,Hardy, p. 230 and the women's 1st VIII of 1993 won their "blades" in the first divisions of both Torpids and Eights Week, an achievement that led to the crew being described in the ''Jesus College Record'' as vying "not just for the College team of the decade, but perhaps for the team of the last three decades", in any sport.

A number of college members have rowed for the university against

Education in

Education in

MCR (postgraduates) website

JCR (undergraduates) website

''Jesus College Oxford 'of Queene Elizabeth's Foundation' - The First 450 Years'': text of 2021 book

Virtual Tour of Jesus College

{{Authority control 1571 establishments in England Colleges of the University of Oxford Educational institutions established in the 1570s Culture of Wales Elizabeth I

Somerville College

Somerville College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The college's liberal tone derives from its f ...

. The last ball was held in April 2022.

Sports

In common with many Oxford colleges, Jesus provides sporting facilities for students, including playing fields at a site in east Oxford off the Cowley Road known as Bartlemas (for its proximity to St Bartholomew's Chapel). Football, rugby, netball, field hockey, cricket, and tennis can be played there. Squash courts are at a separate city-centre site on St Cross Road. The college also provides students with membership of the university's gym and swimming pool on Iffley Road.

Jesus College Boat Club (commonly abbreviated to JCBC) is the rowing club for members of the college. The club was formed in 1835, but rowing at the college predates the foundation of the club: a boat from the college was involved in the earliest recorded races between college crews at Oxford in 1815, when it competed against a crew from Brasenose College. These may have been the only two colleges who had boats racing at that time, and the Brasenose boat was usually victorious.Hardy, p. 229 Neither the men's nor the women's 1st VIIIs have been "Head of the River" during Eights Week, the main college races, but the women's 1st VIII was Head of the River in the spring races, Torpids, between 1980 and 1983. Jesus boats have also had other successful seasons: the 1896 Jesus College boat had a reputation of being one of the faster boats in the university,Hardy, p. 230 and the women's 1st VIII of 1993 won their "blades" in the first divisions of both Torpids and Eights Week, an achievement that led to the crew being described in the ''Jesus College Record'' as vying "not just for the College team of the decade, but perhaps for the team of the last three decades", in any sport.

A number of college members have rowed for the university against