James, Duke Of York on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was

In August 1642, long running political disputes between Charles I and his opponents in

In August 1642, long running political disputes between Charles I and his opponents in

James, like his brother, sought refuge in France, serving in the French army under Turenne against the Fronde, and later against their Spanish allies. In the French army James had his first true experience of battle, in which, according to one observer, he "ventures himself and chargeth gallantly where anything is to be done". Turenne's favour led to James being given command of a captured Irish regiment in December 1652, then appointed Lieutenant-General in 1654.

In 1657, France, then engaged in the

James, like his brother, sought refuge in France, serving in the French army under Turenne against the Fronde, and later against their Spanish allies. In the French army James had his first true experience of battle, in which, according to one observer, he "ventures himself and chargeth gallantly where anything is to be done". Turenne's favour led to James being given command of a captured Irish regiment in December 1652, then appointed Lieutenant-General in 1654.

In 1657, France, then engaged in the

After the collapse of the

After the collapse of the

After the Restoration, James was confirmed as Lord High Admiral, an office that carried with it the subsidiary appointments of Governor of

After the Restoration, James was confirmed as Lord High Admiral, an office that carried with it the subsidiary appointments of Governor of

James's time in France had exposed him to the beliefs and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church, and both he and his wife Anne became drawn to that faith. James took Catholic

James's time in France had exposed him to the beliefs and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church, and both he and his wife Anne became drawn to that faith. James took Catholic

In 1688, James ordered the Declaration read from the pulpits of every Anglican church, further alienating the Anglican bishops against the Supreme Governor of their church. While the Declaration elicited some thanks from its beneficiaries, it left the Established Church, the traditional ally of the monarchy, in the difficult position of being forced to erode its own privileges. James provoked further opposition by attempting to reduce the Anglican monopoly on education. At the

In 1688, James ordered the Declaration read from the pulpits of every Anglican church, further alienating the Anglican bishops against the Supreme Governor of their church. While the Declaration elicited some thanks from its beneficiaries, it left the Established Church, the traditional ally of the monarchy, in the difficult position of being forced to erode its own privileges. James provoked further opposition by attempting to reduce the Anglican monopoly on education. At the

With the assistance of French troops, James landed in Ireland in March 1689. The Irish Parliament did not follow the example of the English Parliament; it declared that James remained King and passed a massive

With the assistance of French troops, James landed in Ireland in March 1689. The Irish Parliament did not follow the example of the English Parliament; it declared that James remained King and passed a massive

Historical analysis of James II has been somewhat revised since Whig historians, led by Lord Macaulay, cast James as a cruel absolutist and his reign as "tyranny which approached to insanity". Subsequent scholars, such as G. M. Trevelyan (Macaulay's great-nephew) and David Ogg, while more balanced than Macaulay, still characterised James as a tyrant, his attempts at religious tolerance as a fraud, and his reign as an aberration in the course of British history. In 1892, A. W. Ward wrote for the

Historical analysis of James II has been somewhat revised since Whig historians, led by Lord Macaulay, cast James as a cruel absolutist and his reign as "tyranny which approached to insanity". Subsequent scholars, such as G. M. Trevelyan (Macaulay's great-nephew) and David Ogg, while more balanced than Macaulay, still characterised James as a tyrant, his attempts at religious tolerance as a fraud, and his reign as an aberration in the course of British history. In 1892, A. W. Ward wrote for the

James VII & II

at the official website of the

James II

at the official website of the

James II

at BBC History * {{DEFAULTSORT:James 02 Of England 1633 births 1701 deaths 17th-century English monarchs 17th-century Scottish monarchs 17th-century Irish monarchs 18th-century British people 17th-century English nobility 17th-century Scottish peers Dukes of Normandy Jacobite pretenders

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

as James II and King of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685, until he was deposed in the 1688 Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

. The last Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

monarch of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, his reign is now remembered primarily for conflicts over religion. However, it also involved struggles over the principles of absolutism and divine right of kings, with his deposition ending a century of political and civil strife by confirming the primacy of the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised th ...

over the Crown.

James was the second surviving son of Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649.

Charles was born ...

and Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France ( French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649. She was ...

, and was created Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

at birth. He succeeded to the throne aged 51 with widespread support. The general public were reluctant to undermine the principle of hereditary succession after the trauma of the brief republican Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

25 years before, and believed that a Catholic monarchy was purely temporary. However, tolerance of James's personal views did not extend to Catholicism in general, and both the English and Scottish parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( ; ) is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. It is located in the Holyrood, Edinburgh, Holyrood area of Edinburgh, and is frequently referred to by the metonym 'Holyrood'. ...

s refused to pass measures viewed as undermining the primacy of the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

religion. His attempts to impose them by absolutist decrees as a matter of his divine right met with opposition.

In June 1688, two events turned dissent into a crisis. Firstly, the birth of James's son and heir James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart (10 June 16881 January 1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender by Whigs (British political party), Whigs or the King over the Water by Jacobitism, Jacobites, was the House of Stuart claimant to the thrones of Ki ...

on 10 June raised the prospect of a Catholic dynasty, excluding his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William III, Prince of Orange

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrec ...

, who was also his nephew. Secondly, the prosecution of the Seven Bishops

The Seven Bishops were members of the Church of England tried and acquitted for seditious libel in the Court of Kings Bench in June 1688. The very unpopular prosecution of the bishops is viewed as a significant event contributing to the Novemb ...

was seen as an assault on the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, and their acquittal on 30 June destroyed his political authority. Ensuing anti-Catholic riots in England and Scotland led to a general feeling that only James's removal could prevent another civil war.

Leading members of the English political class invited William to assume the English throne. When William landed in Brixham

Brixham is a coastal town and civil parish in the borough of Torbay in the county of Devon, in the south-west of England. As of the 2021 census, Brixham had a population of 16,825. It is one of the main three centres of the borough, along with ...

on 5 November 1688, James's army deserted and he went into exile in France on 23 December. In February 1689, a special Convention Parliament held James had "vacated" the English throne and installed William and Mary as joint monarchs, thereby establishing the principle that sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

derived from Parliament, not birth. James landed in Ireland on 14 March 1689 in an attempt to recover his kingdoms, but, despite a simultaneous rising in Scotland, in April a Scottish Convention followed England in ruling that James had "forfeited" the throne, which was offered to William and Mary.

After his defeat at the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

in July 1690, James returned to France, where he spent the rest of his life in exile at Saint-Germain, protected by Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

. While contemporary opponents often portrayed him as an absolutist tyrant, some 20th-century historians have praised James for advocating religious tolerance, although more recent scholarship has tended to take a middle ground between these views.

Early life

Birth

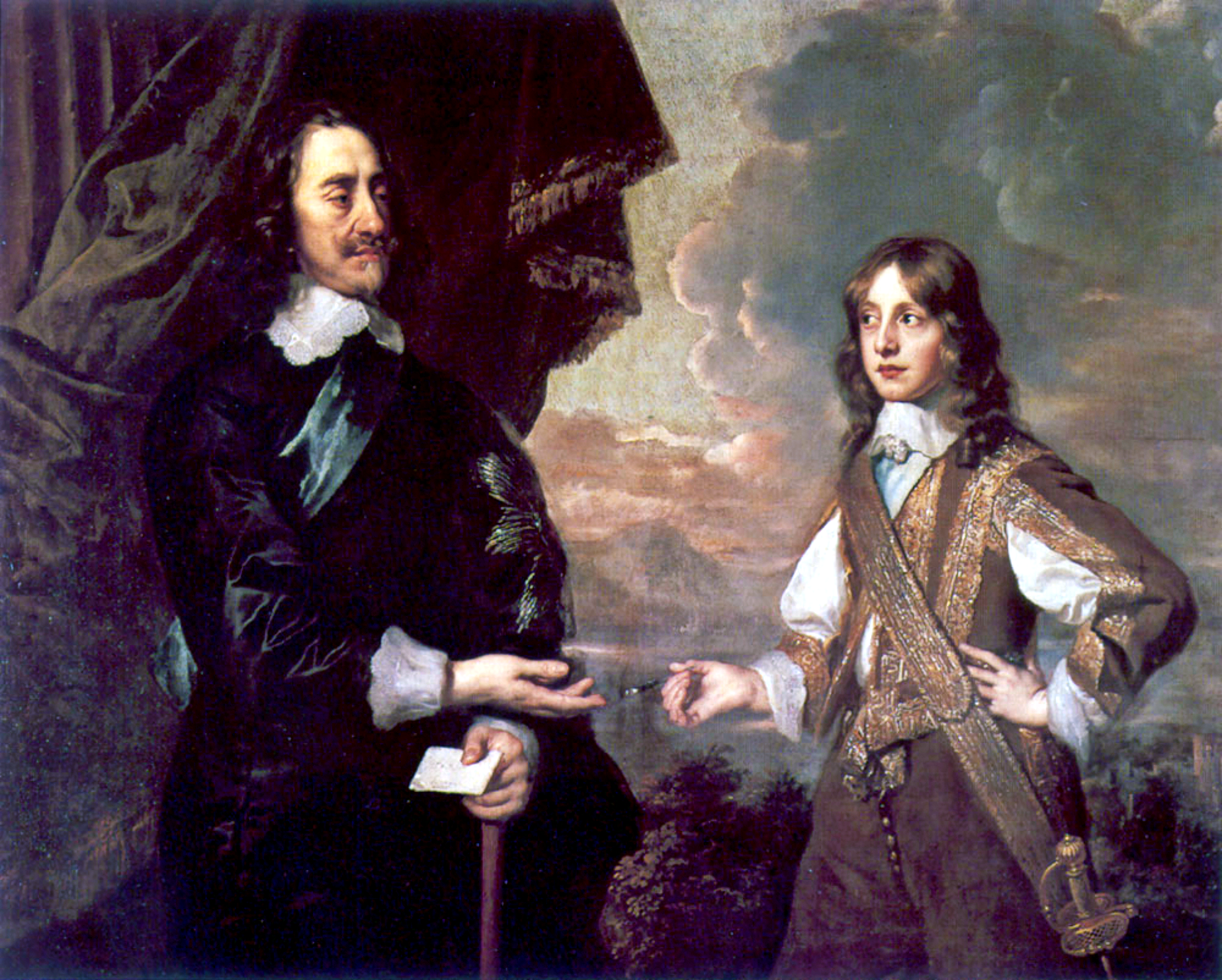

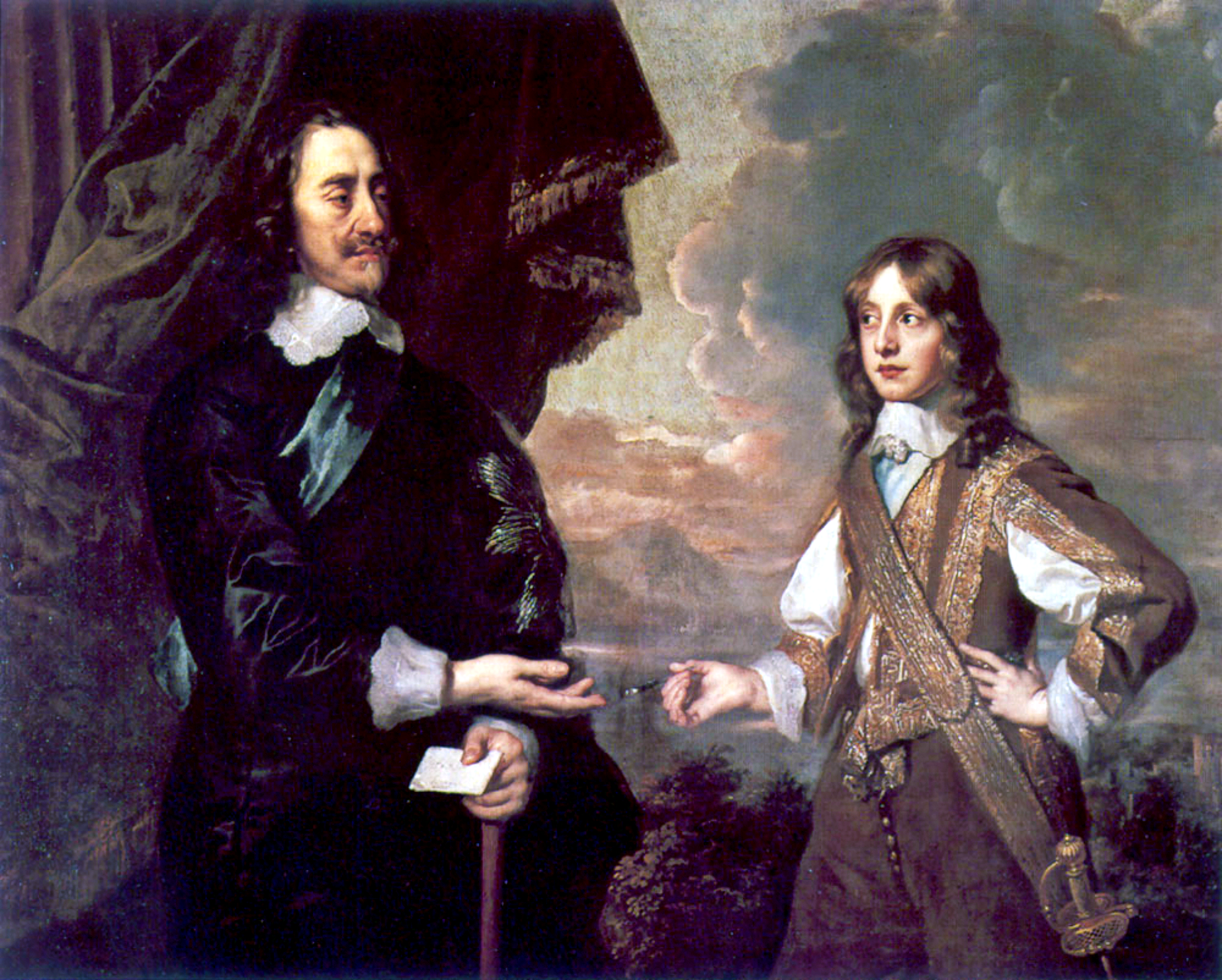

James, second surviving son of King Charles I and his wife,Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France ( French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649. She was ...

, was born at St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, England. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster. Although no longer the principal residence ...

in London on 14 October 1633. Later that same year, he was baptized by William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

. He was educated by private tutors, along with his older brother, the future King Charles II, and the two sons of the Duke of Buckingham, George and Francis Villiers. At the age of three, James was appointed Lord High Admiral; the position was initially honorary, but became a substantive office after the Restoration, when James was an adult. He was designated Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

at birth, invested with the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

in 1642, and formally created Duke of York in January 1644.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

In August 1642, long running political disputes between Charles I and his opponents in

In August 1642, long running political disputes between Charles I and his opponents in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

led to the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. An estimated 15% to 20% of adult males in England and Wales served in the military at some point b ...

. James and his brother Charles were present at the Battle of Edgehill in October, and narrowly escaped capture by Parliamentarian cavalry. He spent most of the next four years in the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

wartime capital of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, where he was made a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

by the University on 1 November 1642 and served as colonel of a volunteer regiment of foot. Following the surrender of Oxford in June 1646, James was taken to London and held with his younger siblings Henry, Elizabeth and Henrietta in St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, England. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster. Although no longer the principal residence ...

.

Frustrated by their inability to agree terms with Charles I, and with his brother Charles out of reach in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Parliament considered making James king. James was ordered by his father to escape, and, with the help of Joseph Bampfield, in April 1648 successfully evaded his guards and crossed the North Sea to The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

. Following their victory in the 1648 Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February and August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639–1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 164 ...

, Parliament ordered the execution of Charles I

Charles_I_of_England, Charles I, King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, was executed on Tuesday, 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall, London. The execution was ...

in January 1649. The Covenanter

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son C ...

regime proclaimed Charles II King of Scotland, and after lengthy negotiations agreed to provide troops to restore him to the English throne. The invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

ended in defeat at Worcester in September 1651. Although Charles managed to escape capture and to return to the exiled court in Paris, the Royalist cause appeared hopeless.

Exile in France

James, like his brother, sought refuge in France, serving in the French army under Turenne against the Fronde, and later against their Spanish allies. In the French army James had his first true experience of battle, in which, according to one observer, he "ventures himself and chargeth gallantly where anything is to be done". Turenne's favour led to James being given command of a captured Irish regiment in December 1652, then appointed Lieutenant-General in 1654.

In 1657, France, then engaged in the

James, like his brother, sought refuge in France, serving in the French army under Turenne against the Fronde, and later against their Spanish allies. In the French army James had his first true experience of battle, in which, according to one observer, he "ventures himself and chargeth gallantly where anything is to be done". Turenne's favour led to James being given command of a captured Irish regiment in December 1652, then appointed Lieutenant-General in 1654.

In 1657, France, then engaged in the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659)

The Franco-Spanish War , May 1635 to November 1659, was fought between Kingdom of France, France and Habsburg Spain, Spain, each supported by various allies at different points. The first phase, beginning in May 1635 and ending with the 1648 Peac ...

, agreed an alliance with the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

, and when Charles responded by signing a treaty with Spain, James was expelled from France. James quarrelled with his brother over this choice, but ultimately joined Spanish forces in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

led by the French exile Condé. Given command of six regiments of British volunteers, he fought against his former French comrades at the Battle of the Dunes.

After France and Spain made peace with the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees, James considered taking a Spanish offer to be an admiral in their navy, but declined the position. Soon after, the 1660 Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

returned his brother to the English throne as Charles II.

Restoration

First marriage

After the collapse of the

After the collapse of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

in 1660, Charles II was restored to the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland. Although James was the heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

, it seemed unlikely that he would inherit the Crown, as Charles was still a young man capable of fathering children. On 31 December 1660, following his brother's restoration, James was created Duke of Albany

Duke of Albany is a peerage title that has occasionally been bestowed on younger sons in the Scotland, Scottish and later the British royal family, particularly in the Houses of House of Stuart, Stuart and House of Hanover, Hanover.

History ...

in Scotland, to go along with his English title, Duke of York. Upon his return to England, James prompted an immediate controversy by announcing his engagement to Anne Hyde, the daughter of Charles's chief minister, Edward Hyde.

In 1659, while trying to seduce her, James promised he would marry Anne. Anne became pregnant in 1660, but following the Restoration and James's return to power, no one at the royal court expected a prince to marry a commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

, no matter what he had pledged beforehand. Although nearly everyone, including Anne's father, urged the two not to marry, the couple married secretly, then went through an official marriage ceremony on 3 September 1660 in London.

The couple's first child, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

, was born less than two months later, but died in infancy, as did five further children. Only two daughters survived: Mary (born 30 April 1662) and Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

(born 6 February 1665). Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

wrote that James was fond of his children and his role as a father, and played with them "like an ordinary private father of a child", a contrast to the distant parenting common with royalty at the time.

James's wife was devoted to him and influenced many of his decisions. Even so, he kept mistresses, including Arabella Churchill and Catherine Sedley, and was reputed to be "the most unguarded ogler of his time". Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that James "did eye my wife mightily". James's taste in women was often maligned, with Gilbert Burnet famously remarking that James's mistresses must have been "given ohim by his priests as a penance". Anne Hyde died in 1671.

Military and political offices and royal slavery

After the Restoration, James was confirmed as Lord High Admiral, an office that carried with it the subsidiary appointments of Governor of

After the Restoration, James was confirmed as Lord High Admiral, an office that carried with it the subsidiary appointments of Governor of Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

. Charles II also made his brother the Governor of the Royal Adventurers into Africa (later shortened to the Royal African Company) in October 1660, an office James retained until after the Glorious Revolution when he was forced to resign. When James commanded the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

during the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

(1665–1667) he immediately directed the fleet towards the capture of forts off the African coast that would facilitate English involvement in the slave trade (indeed English attacks on such forts occupied by the Dutch precipitated the war itself). James remained Admiral of the Fleet during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), during which significant fighting also occurred off the African coast. Following the raid on the Medway in 1667, James oversaw the survey and re-fortification of the southern coast. The office of Lord High Admiral, combined with his revenue from post office and wine tariffs (positions granted him by Charles II upon his restoration), gave James enough money to keep a sizable court household.

In 1664, Charles II granted American territory between the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

rivers to James. Following its capture by the British, the former Dutch territory of New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

and its principal port, New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

, were renamed the Province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

and City of New York in James's honour. James gave part of the colony to proprietors George Carteret and John Berkeley. Fort Orange

Fort Orange () was the first permanent Dutch settlement in New Netherland; the present-day city and state capital Albany, New York developed near this site. It was built in 1624 as a replacement for Fort Nassau, which had been built on n ...

, north on the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

, was renamed Albany after James's Scottish title. In 1683, James became the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

, but did not take an active role in its governance.

In September 1666, Charles II put James in charge of firefighting operations during the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Wednesday 5 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old London Wall, Roman city wall, while also extendi ...

, in the absence of action by Lord Mayor Thomas Bloodworth. This was not a political office, but his actions and leadership were noteworthy. "The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the Fire", wrote a witness in a letter on 8 September.

In 1672, the Royal African Company received a new charter from Charles II. It set up forts and factories, maintained troops, and exercised martial law in West Africa in pursuit of trade in gold, silver and African slaves. In the 1680s, the RAC transported about 5,000 slaves a year to markets primarily in the English Caribbean across the Atlantic. Many were branded on the chest with the letters "DY" for "Duke of York", the RAC's Governor. As historian William Pettigrew writes, the RAC "shipped more enslaved African women, men, and children to the Americas than any other single institution during the entire period of the transatlantic slave trade".

Conversion to Roman Catholicism and second marriage

James's time in France had exposed him to the beliefs and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church, and both he and his wife Anne became drawn to that faith. James took Catholic

James's time in France had exposed him to the beliefs and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church, and both he and his wife Anne became drawn to that faith. James took Catholic Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

in 1668 or 1669, although his conversion was kept secret for almost a decade as he continued to attend Anglican services until 1676. In spite of his conversion, James continued to associate primarily with Anglicans, including John Churchill and George Legge, as well as French Protestants

Protestantism in France has existed in its various forms, starting with Calvinism and Lutheranism since the Protestant Reformation. John Calvin was a Frenchman, as were numerous other Protestant Reformers including William Farel, Pierre Viret and ...

such as Louis de Duras, 2nd Earl of Feversham

Colonel Louis de Duras, 2nd Earl of Feversham, KG (19 April 1709) was an English Army officer. Born in the Kingdom of France, he was marquis de Blanquefort and sixth son of Guy Aldonce, Marquis of Duras and Count of Rozan, from the noble Durf ...

.

Growing fears of Roman Catholic influence at court led the English Parliament to introduce a new Test Act in 1673. Under this Act, all civil and military officials were required to take an oath (in which they were required to disavow the doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

and denounce certain practices of the Roman Church as superstitious and idolatrous) and to receive the Eucharist under the auspices of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. James refused to perform either action, instead choosing to relinquish the post of Lord High Admiral. His conversion to Roman Catholicism was thereby made public.

King Charles II opposed James's conversion, ordering that James's daughters, Mary and Anne, be raised in the Church of England. Nevertheless, he allowed the widowed James to marry Mary of Modena, a fifteen-year-old Italian princess. James and Mary were married by proxy in a Roman Catholic ceremony on 20 September 1673. On 21 November, Mary arrived in England and Nathaniel Crew, Bishop of Oxford

The Bishop of Oxford is the diocesan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Oxford in the Province of Canterbury; his seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The current bishop is Steven Croft (bishop), Steven Croft, following the Confirm ...

, performed a brief Anglican service that did little more than recognise the marriage by proxy. Many British people, distrustful of Catholicism, regarded the new Duchess of York as an agent of the Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. James was noted for his deep devotion, once remarking, "If occasion were, I hope God would give me his grace to suffer death for the true Catholic religion as well as banishment."

Exclusion Crisis

In 1677, King Charles II arranged for James's daughter Mary to marry the Protestant PrinceWilliam III of Orange

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 167 ...

, son of Charles's and James's sister Mary. James reluctantly acquiesced after his brother and nephew had agreed to the marriage. Despite the Protestant marriage, fears of a potential Catholic monarch persisted, intensified by the failure of Charles II and his wife, Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza (; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, King Charles II, which la ...

, to produce any children. A defrocked Anglican clergyman, Titus Oates, spoke of a " Popish Plot" to kill Charles and to put the Duke of York on the throne. The fabricated plot caused a wave of anti-Catholic hysteria to sweep across the nation.

In England, the Earl of Shaftesbury, a former government minister and now a leading opponent of Catholicism, proposed an Exclusion Bill that would have excluded James from the line of succession. Some members of Parliament even proposed to pass the crown to Charles's illegitimate son, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, (9 April 1649 – 15 July 1685) was an English nobleman and military officer. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, the eldest ill ...

. In 1679, with the Exclusion Bill in danger of passing, Charles II dissolved Parliament. Two further Parliaments were elected in 1680 and 1681, but were dissolved for the same reason. The Exclusion Crisis contributed to the development of the English two-party system: the Whigs were those who supported the Bill, while the Tories were those who opposed it. Ultimately, the succession was not altered, but James was convinced to withdraw from all policy-making bodies and to accept a lesser role in his brother's government.

On the orders of the King, James left England for Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

. In 1680, he was appointed Lord High Commissioner of Scotland and took up residence at the Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly known as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood has s ...

in Edinburgh to suppress an uprising and oversee the royal government. James returned to England for a time when Charles was stricken ill and appeared to be near death. The hysteria of the accusations eventually faded, but James's relations with many in the English Parliament, including the Earl of Danby, a former ally, were forever strained and a solid segment turned against him.

On 6 May 1682, James narrowly escaped the sinking of HMS ''Gloucester'', in which between 130 and 250 people perished. James argued with the pilot about the navigation of the ship before it ran aground on a sandbank, and then delayed abandoning ship, which may have contributed to the death toll.

Return to favour

In 1683, a plot was uncovered to assassinate Charles II and his brother and spark a republican revolution to re-establish a government of the Cromwellian style. The conspiracy, known as the Rye House Plot, backfired upon its conspirators and provoked a wave of sympathy for the King and James. Several notable Whigs, including theEarl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

and the Duke of Monmouth, were implicated. Monmouth initially confessed to complicity in the plot and implicated fellow conspirators, but later recanted. Essex committed suicide, and Monmouth, along with several others, was obliged to flee into exile in continental Europe. Charles II reacted to the plot by increasing the repression of Whigs and dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

. Taking advantage of James's rebounding popularity, Charles invited him back onto the Privy Council in 1684. While some in the English Parliament remained wary of the possibility of a Roman Catholic king, the threat of excluding James from the throne had passed.

Reign

Accession to the throne

Charles II died on 6 February 1685 fromapoplexy

Apoplexy () refers to the rupture of an internal organ and the associated symptoms. Informally or metaphorically, the term ''apoplexy'' is associated with being furious, especially as "apoplectic". Historically, it described what is now known as a ...

, after supposedly converting to Catholicism on his deathbed. Having no legitimate children, he was succeeded by his brother James, who reigned in England and Ireland as James II and in Scotland as James VII. There was little initial opposition to James's accession, and there were widespread reports of public rejoicing at the orderly succession. He wished to proceed quickly to the coronation, and he and Mary were crowned at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

on 23 April 1685.

The new Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

that assembled in May 1685, which gained the name of " Loyal Parliament", was initially favourable to James, who had stated that most former exclusionists would be forgiven if they acquiesced to his rule. Most of Charles's officers continued in office, the exceptions being the promotion of James's brothers-in-law, the earls of Clarendon and Rochester, and the demotion of Halifax. Parliament granted James a generous life income, including all of the proceeds of tonnage and poundage and the customs duties. James worked harder as king than his brother had, but was less willing to compromise when his advisers disagreed with his policies.

Two rebellions

Soon after becoming king, James faced a rebellion in southern England led by his nephew, the Duke of Monmouth, and another rebellion in Scotland led byArchibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll

Archibald may refer to:

People and characters

*Archibald (name), a masculine given name and a surname

* Archibald (musician) (1916–1973), American R&B pianist

* Archibald, a character from the animated TV show '' Archibald the Koala''

Other us ...

. Monmouth and Argyll both began their expeditions from Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, where James's nephew and son-in-law, the Prince of Orange, had neglected to detain them or put a stop to their recruitment efforts.

Argyll sailed to Scotland where he raised recruits, mainly from his own clan, the Campbells. The rebellion was quickly crushed, and Argyll was captured at Inchinnan on 18 June 1685. Having arrived with fewer than 300 men and unable to convince many more to flock to his standard, he never posed a credible threat to James. Argyll was taken as a prisoner to Edinburgh. A new trial was not commenced because Argyll had previously been tried and sentenced to death. The King confirmed the earlier death sentence and ordered that it be carried out within three days of receiving the confirmation.

Monmouth's rebellion was coordinated with Argyll's, but was more dangerous to James. Monmouth had proclaimed himself King at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

on 11 June. He attempted to raise recruits but was unable to gather enough rebels to defeat even James's small standing army. Monmouth's soldiers attacked the King's army at night, in an attempt at surprise, but were defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor

The Battle of Sedgemoor was the last and decisive engagement between forces loyal to James II and rebels led by the Duke of Monmouth during the Monmouth rebellion, fought on 6 July 1685, and took place at Westonzoyland near Bridgwater in S ...

. The King's forces, led by Feversham and Churchill, quickly dispersed the ill-prepared rebels. Monmouth was captured and later executed at the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

on 15 July. The King's judges—most notably, George Jeffreys—condemned many of the rebels to transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

and indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an " indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or s ...

in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

in a series of trials that came to be known as the Bloody Assizes. Around 250 of the rebels were executed. While both rebellions were defeated easily, they hardened James's resolve against his enemies and increased his suspicion of the Dutch.

Religious liberty and dispensing power

To protect himself from further rebellions, James sought safety by enlarging hisstanding army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

. This alarmed his subjects, not only because of the trouble soldiers caused in the towns, but because it was against the English tradition to keep a professional army in peacetime. Even more alarming to Parliament was James's use of his dispensing power to allow Roman Catholics to command several regiments without having to take the oath mandated by the Test Act. When even the previously supportive Parliament objected to these measures, James ordered Parliament prorogued in November 1685, never to meet again in his reign. At the beginning of 1686, two papers were found in Charles II's strong box and his closet, in his own hand, stating the arguments for Catholicism over Protestantism. James published these papers with a declaration signed by his sign manual and challenged the Archbishop of Canterbury and the whole Anglican episcopal bench to refute Charles's arguments: "Let me have a solid answer, and in a gentlemanlike style; and it may have the effect which you so much desire of bringing me over to your church." The Archbishop refused on the grounds of respect for the late king.

James advocated repeal

A repeal (O.F. ''rapel'', modern ''rappel'', from ''rapeler'', ''rappeler'', revoke, ''re'' and ''appeler'', appeal) is the removal or reversal of a law. There are two basic types of repeal; a repeal with a re-enactment is used to replace the law ...

of the penal laws in all three of his kingdoms, but in the early years of his reign he refused to allow those dissenters who did not petition for relief to receive it. James sent a letter to the Scottish Parliament at its opening in 1685, declaring his wish for new penal laws against refractory Presbyterians and lamented that he was not there in person to promote such a law. In response, the Parliament passed an Act that stated, "whoever should preach in a conventicle under a roof, or should attend, either as preacher or as a hearer, a conventicle in the open air, should be punished with death and confiscation of property". In March 1686, James sent a letter to the Scottish Privy Council advocating toleration for Roman Catholics but not for rebellious Presbyterian Covenanters. Presbyterians would later call this period " The Killing Time".

James allowed Roman Catholics to occupy the highest offices of his kingdoms, and received at his court the papal nuncio, Ferdinando d'Adda, the first representative from Rome to London since the reign of Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

. Edward Petre, James's Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

confessor, was a particular object of Anglican ire. When the King's Secretary of State, the Earl of Sunderland, began replacing office-holders at court with "Papist" favourites, James began to lose the confidence of many of his Anglican supporters. Sunderland's purge of office-holders even extended to the King's brothers-in-law (the Hydes) and their supporters. Roman Catholics made up no more than one-fiftieth of the English population. In May 1686, James sought to obtain a ruling from the English common-law courts that showed he had the power to dispense with Acts of Parliament. He dismissed judges who disagreed with him on this matter, as well as the Solicitor General, Heneage Finch. The case of '' Godden v Hales'' affirmed his dispensing power, with eleven out of the twelve judges ruling in the king's favour after six judges were dismissed for refusing to promise to support the king.

In 1687, James issued the Declaration of Indulgence Declaration of Indulgence may refer to:

* Declaration of Indulgence (1672) by Charles II of England in favour of nonconformists and Catholics

* Declaration of Indulgence (1687) by James II of England granting religious freedom

See also

*Indulgence ...

, also known as the Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, in which he used his dispensing power to negate the effect of laws punishing both Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

. In the summer of 1687 he attempted to increase support for his tolerationist policy by a speaking tour of the western counties of England. As part of this tour, he gave a speech at Chester in which he said, "suppose... there should be a law made that all black men should be imprisoned, it would be unreasonable and we had as little reason to quarrel with other men for being of different eligiousopinions as for being of different complexions." At the same time, James provided partial toleration in Scotland, using his dispensing power to grant relief to Roman Catholics and partial relief to Presbyterians.

In 1688, James ordered the Declaration read from the pulpits of every Anglican church, further alienating the Anglican bishops against the Supreme Governor of their church. While the Declaration elicited some thanks from its beneficiaries, it left the Established Church, the traditional ally of the monarchy, in the difficult position of being forced to erode its own privileges. James provoked further opposition by attempting to reduce the Anglican monopoly on education. At the

In 1688, James ordered the Declaration read from the pulpits of every Anglican church, further alienating the Anglican bishops against the Supreme Governor of their church. While the Declaration elicited some thanks from its beneficiaries, it left the Established Church, the traditional ally of the monarchy, in the difficult position of being forced to erode its own privileges. James provoked further opposition by attempting to reduce the Anglican monopoly on education. At the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, he offended Anglicans by allowing Roman Catholics to hold important positions in Christ Church and University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

, two of Oxford's largest colleges. He also attempted to force the Fellows of Magdalen College to elect as their President Anthony Farmer, a man of generally ill repute who was believed to be a Roman Catholic, which was seen as a violation of the Fellows' right to elect someone of their own choosing.

In 1687, James prepared to pack Parliament with his supporters, so that it would repeal the Test Act and the Penal Laws. James was convinced by addresses from Dissenters that he had their support and so could dispense with relying on Tories and Anglicans. He instituted a wholesale purge of those in offices under the Crown opposed to his plan, appointing new lord-lieutenants of counties and remodelling the corporations governing towns and livery companies

A livery company is a type of guild or professional association that originated in medieval times in London, England. Livery companies comprise London's ancient and modern trade associations and guilds, almost all of which are Style (form of a ...

. In October, James gave orders for the lord-lieutenants to provide three standard questions to all Justices of the Peace: 1. Would they consent to the repeal of the Test Act and the Penal Laws? 2. Would they assist candidates who would do so? 3. Would they accept the Declaration of Indulgence? During the first three months of 1688, hundreds of those who gave negative replies to those questions were dismissed. Corporations were purged by agents, known as the Regulators, who were given wide discretionary powers, in an attempt to create a permanent royal electoral machine. Most of the regulators were Baptists

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

, and the new town officials that they recommended included Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

, Baptists, Congregationalists

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

, Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

and Roman Catholics, as well as Anglicans. Finally, on 24 August 1688, James ordered the issue of writs for a general election. However, upon realising in September that William of Orange was going to land in England, James withdrew the writs and subsequently wrote to the lord-lieutenants to inquire over allegations of abuses committed during the regulations and election preparations, as part of the concessions he made to win support.

Deposition and the Glorious Revolution

In April 1688, James re-issued the Declaration of Indulgence, subsequently ordering Anglican clergy to read it in their churches. Whenseven bishops

The Seven Bishops were members of the Church of England tried and acquitted for seditious libel in the Court of Kings Bench in June 1688. The very unpopular prosecution of the bishops is viewed as a significant event contributing to the Novemb ...

, including the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, submitted a petition requesting the reconsideration of the King's religious policies, they were arrested and tried for seditious libel. Public alarm increased when Queen Mary gave birth to a Roman Catholic son and heir, James Francis Edward, on 10 June that year. When James's only possible successors were his two Protestant daughters, Anglicans could see his pro-Catholic policies as a temporary phenomenon, but when the prince's birth opened the possibility of a permanent Roman Catholic dynasty, such men had to reconsider their position. Threatened by a Roman Catholic dynasty, several influential Protestants claimed the child was supposititious and had been smuggled into the Queen's bedchamber in a warming pan. They had already entered into negotiations with the Prince of Orange when it became known the Queen was pregnant, and the birth of a son reinforced their convictions.

On 30 June 1688, a group of seven Protestant nobles invited William, Prince of Orange, to come to England with an army. By September, it had become clear that William sought to invade. Believing that his own army would be adequate, James refused the assistance of King Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

of France, fearing that the English would oppose French intervention. When William arrived on 5 November 1688, many Protestant officers, including Churchill, defected and joined William, as did James's own daughter Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

. James lost his nerve and declined to attack the invading army, despite his army's numerical superiority. On 11 December, James tried to flee to France, first throwing the Great Seal of the Realm

The Great Seal of the Realm is a seal that is used in the United Kingdom to symbolise the sovereign's approval of state documents. It is also known as the Great Seal of the United Kingdom (known prior to the Treaty of Union of 1707 as the Gr ...

into the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

. He was captured in Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

; later, he was released and placed under Dutch protective guard. Having no desire to make James a martyr, William let him escape on 23 December. James was received by his cousin and ally, Louis XIV, who offered him a palace and a pension.

William summoned a Convention Parliament to decide how to handle James's flight. It convened on 22 January 1689. While the Parliament refused to depose him, they declared that James, having fled to France and dropped the Great Seal into the Thames, had effectively abdicated, and that the throne had thereby become vacant. To fill this vacancy, James's daughter Mary was declared Queen; she was to rule jointly with her husband William, who would be King. On 11 April 1689, the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

declared James to have forfeited the throne of Scotland as well. The Convention Parliament issued a Declaration of Right on 12 February that denounced James for abusing his power, and proclaimed many limitations on royal authority. The abuses charged to James included the suspension of the Test Acts, the prosecution of the Seven Bishops for merely petitioning the Crown, the establishment of a standing army, and the imposition of cruel punishments. The Declaration was the basis for the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

enacted later in 1689. The Bill also declared that henceforth, no Roman Catholic was permitted to ascend the English throne, nor could any English monarch marry a Roman Catholic.

Attempt to regain the throne

War in Ireland

With the assistance of French troops, James landed in Ireland in March 1689. The Irish Parliament did not follow the example of the English Parliament; it declared that James remained King and passed a massive

With the assistance of French troops, James landed in Ireland in March 1689. The Irish Parliament did not follow the example of the English Parliament; it declared that James remained King and passed a massive bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder, writ of attainder, or bill of pains and penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and providing for a punishment, often without a ...

against those who had rebelled against him. At James's urging, the Irish Parliament passed an Act for Liberty of Conscience that granted religious freedom to all Roman Catholics and Protestants in Ireland. James worked to build an army in Ireland, but was ultimately defeated at the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

on 1 July 1690 O.S. when William arrived, personally leading an army to defeat James and reassert English control. James fled to France once more, departing from Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork (city), Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a populatio ...

, never to return to any of his former kingdoms. Because he deserted his Irish supporters, James became known in Ireland as ''Séamus an Chaca'' or "James the shit". Despite this popular perception, later historian Breandán Ó Buachalla argues that "Irish political poetry for most of the eighteenth century is essentially Jacobite poetry", and both Ó Buachalla and fellow-historian Éamonn Ó Ciardha

Éamonn Ó Ciardha is an Irish historian and writer.

Biography

Ó Ciardha is a native of Scotshouse, a village in the Barony of Dartree in the west of County Monaghan. Townlands.ie: Barony of Dartree, Co. Monaghan. https://www.townlands.ie/mo ...

argue that James and his successors played a central role as messianic figures throughout the 18th century for all classes in Ireland.

Return to exile, death and legacy

In France, James was allowed to live in the royal château ofSaint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yvelines Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris. ...

. James's wife and some of his supporters fled with him, including the Earl of Melfort; most, but not all, were Roman Catholic. In 1692, James's last child, Louisa Maria Teresa, was born. Some supporters in England attempted to assassinate William III to restore James to the throne in 1696, but the plot failed and the backlash made James's cause less popular. In the same year, Louis XIV offered to have James elected King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

. James rejected the offer, fearing that accepting the Polish crown might (in the minds of the English people) disqualify him from being King of England. After Louis concluded peace with William in 1697, he ceased to offer much assistance to James.

During his last years, James lived as an austere penitent. He wrote a memorandum for his son advising him on how to govern England, specifying that Catholics should possess one Secretary of State, one Commissioner of the Treasury, the Secretary at War, with the majority of the officers in the army.

James died aged 67 of a brain haemorrhage on 16 September 1701 at Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yvelines Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris. ...

. James's heart was placed in a silver-gilt locket and given to the convent at Chaillot, and his brain was placed in a lead casket and given to the Scots College in Paris. His entrails were placed in two gilt urns and sent to the parish church of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and the English Jesuit college at Saint-Omer, while the flesh from his right arm was given to the English Augustinian nuns of Paris.

The rest of James's body was laid to rest in a triple sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:σάρξ, σάρξ ...

(consisting of two wooden coffins and one of lead) at the St Edmund's Chapel in the Church of the English Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

s in the Rue Saint-Jacques, Paris, with a funeral oration by Henri-Emmanuel de Roquette. James was not buried, but put in one of the side chapels. Lights were kept burning round his coffin until the French Revolution. In 1734, the Archbishop of Paris heard evidence to support James's canonisation, but nothing came of it. During the French Revolution, James's tomb was raided.

Later Hanover succession

James's younger daughterAnne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

succeeded when William died in 1702. The Act of Settlement provided that, if the line of succession established in the Bill of Rights were extinguished, the crown would go to a German cousin, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and to her Protestant heirs. Sophia was a granddaughter of James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 M ...

through his eldest daughter, Elizabeth Stuart, the sister of Charles I. Thus, when Anne died in 1714 (less than two months after the death of Sophia), she was succeeded by George I, Sophia's son, the Elector of Hanover and Anne's second cousin.

Subsequent uprisings and pretenders

James's son James Francis Edward was recognised as king at his father's death by Louis XIV of France and James II's remaining supporters (later known as Jacobites) as "James III and VIII". He led a rising in Scotland in 1715 shortly after George I's accession, but was defeated. His son Charles Edward Stuart led a Jacobite rising in 1745, but was again defeated. The risings were the last serious attempts to restore the Stuart dynasty. Charles's claims passed to his younger brotherHenry Benedict Stuart

Henry Benedict Thomas Edward Maria Clement Francis Xavier Stuart, Cardinal Duke of York (6 March 1725 – 13 July 1807) was a Roman Catholic Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal, and was the third and final Jacobitism, Jacobite heir to pub ...

, the Dean of the College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church. Henry was the last of James II's legitimate descendants. He died childless, and no relative has publicly acknowledged the Jacobite claim since his death in 1807.

Historiography

Historical analysis of James II has been somewhat revised since Whig historians, led by Lord Macaulay, cast James as a cruel absolutist and his reign as "tyranny which approached to insanity". Subsequent scholars, such as G. M. Trevelyan (Macaulay's great-nephew) and David Ogg, while more balanced than Macaulay, still characterised James as a tyrant, his attempts at religious tolerance as a fraud, and his reign as an aberration in the course of British history. In 1892, A. W. Ward wrote for the

Historical analysis of James II has been somewhat revised since Whig historians, led by Lord Macaulay, cast James as a cruel absolutist and his reign as "tyranny which approached to insanity". Subsequent scholars, such as G. M. Trevelyan (Macaulay's great-nephew) and David Ogg, while more balanced than Macaulay, still characterised James as a tyrant, his attempts at religious tolerance as a fraud, and his reign as an aberration in the course of British history. In 1892, A. W. Ward wrote for the Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

that James was "obviously a political and religious bigot", although never devoid of "a vein of patriotic sentiment"; "his conversion to the church of Rome made the emancipation of his fellow-catholics in the first instance, and the recovery of England for catholicism in the second, the governing objects of his policy."

Hilaire Belloc, a writer and Catholic apologist, broke with this tradition in 1928, casting James as an honourable man and a true advocate for freedom of conscience, and his enemies "men in the small clique of great fortunes ... which destroyed the ancient monarchy of the English". However, he observed that James "concluded the Catholic church to be the sole authoritative voice on earth, and thenceforward ... he not only stood firm against surrender but on no single occasion contemplated the least compromise or by a word would modify the impression made."

By the 1960s and 1970s, Maurice Ashley

Maurice Ashley (born March 6, 1966) is a Jamaican and American chess player, author, and commentator. In 1999, he earned the FIDE title of Grandmaster (chess), Grandmaster (GM).

Ashley is well known as a commentator for high-profile chess even ...

and Stuart Prall began to reconsider James's motives in granting religious toleration, while still taking note of James's autocratic rule. Modern historians have moved away from the school of thought that preached the continuous march of progress and democracy, Ashley contending that "history is, after all, the story of human beings and individuals, as well as of the classes and the masses." He cast James II and William III as "men of ideals as well as human weaknesses". John Miller, writing in 2000, accepted the claims of James's absolutism, but argued that "his main concern was to secure religious liberty and civil equality for Catholics. Any 'absolutist' methods ... were essentially means to that end."

In 2004, W. A. Speck wrote in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

that "James was genuinely committed to religious toleration, but also sought to increase the power of the crown." He added that, unlike the government of the Netherlands, "James was too autocratic to combine freedom of conscience with popular government. He resisted any check on the monarch's power. That is why his heart was not in the concessions he had to make in 1688. He would rather live in exile with his principles intact than continue to reign as a limited monarch."

Tim Harris's conclusions from his 2006 book summarised the ambivalence of modern scholarship towards James II:

In 2009, Steven Pincus confronted that scholarly ambivalence in ''1688: The First Modern Revolution.'' Pincus claims that James's reign must be understood within a context of economic change and European politics, and makes two major assertions about James II. The first of these is that James purposefully "followed the French Sun King, Louis XIV, in trying to create a modern Catholic polity. This involved not only trying to Catholicize England ... but also creating a modern, centralizing, and extremely bureaucratic state apparatus." The second is that James was undone in 1688 far less by Protestant reaction against Catholicization than by nationwide hostile reaction against his intrusive bureaucratic state and taxation apparatus, expressed in massive popular support for William of Orange's armed invasion of England. Pincus presents James as neither naïve nor stupid nor egotistical. Instead, readers are shown an intelligent, clear-thinking strategically motivated monarch whose vision for a French authoritarian political model and alliance clashed with, and lost out to, alternative views that favoured an entrepreneurial Dutch economic model, feared French power, and were outraged by James's authoritarianism.