Istanbul Trials Of 1919–1920 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Istanbul trials of 1919–1920 (Turkish: ''Âliye Divan-ı Harb-i Örfi'') were

The Istanbul trials of 1919–1920 (Turkish: ''Âliye Divan-ı Harb-i Örfi'') were

.

The courts-martial were established on 28 April 1919 while the

The courts-martial were established on 28 April 1919 while the

The Istanbul trials of 1919–1920 (Turkish: ''Âliye Divan-ı Harb-i Örfi'') were

The Istanbul trials of 1919–1920 (Turkish: ''Âliye Divan-ı Harb-i Örfi'') were courts-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

that occurred soon after the Armistice of Mudros

The Armistice of Mudros () ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between Ottoman Turkey and the Allies of World War I. It was signed on 30 October 1918 by the Ottoman Minister of Marine Affairs Rauf Bey and British Admiral Somerset ...

, in the aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

, and part of the larger movement to prosecute Ottoman war criminals.

The government of Tevfik Pasha decided to prosecute crimes of Ottoman officials, committed primarily against the Armenian population, in national courts. On 23 November 1918, Sultan Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

created a government commission of inquiry, and Hasan Mazhar Bey was appointed chairman. The formation of a military tribunal investigating the crimes of the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

was a continuation of the work of the Mazhar commission, and on 16 December 1918, the Sultan officially established such tribunals. Three military tribunals and ten provincial courts were created. The tribunals came to be known as "Nemrud's court", after Mustafa "Nemrud" Pasha Yamulki.

The leadership of the CUP and selected former officials were charged with several charges including subversion of the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, wartime profiteering, and the massacres of both Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

and Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

. The court reached a verdict which sentenced the organizers of the massacres – Talat, Enver, and Cemal – and others to death. All those sentenced to death were sent a fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

from the Sheikh al-Islam in the name of Mehmed VI before their execution, as the law stipulated that a Muslim couldn't be executed without a fatwa from the Sultan-Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

.

These trials and fatwas also served as means for Mehmed VI to express his disapproval of the accused and legitimize his position, both in relation to his domestic situation with the Muslims in his empire, in the face of the Western powers that emerged victorious in World War I, and to anti-absolutist politicians.

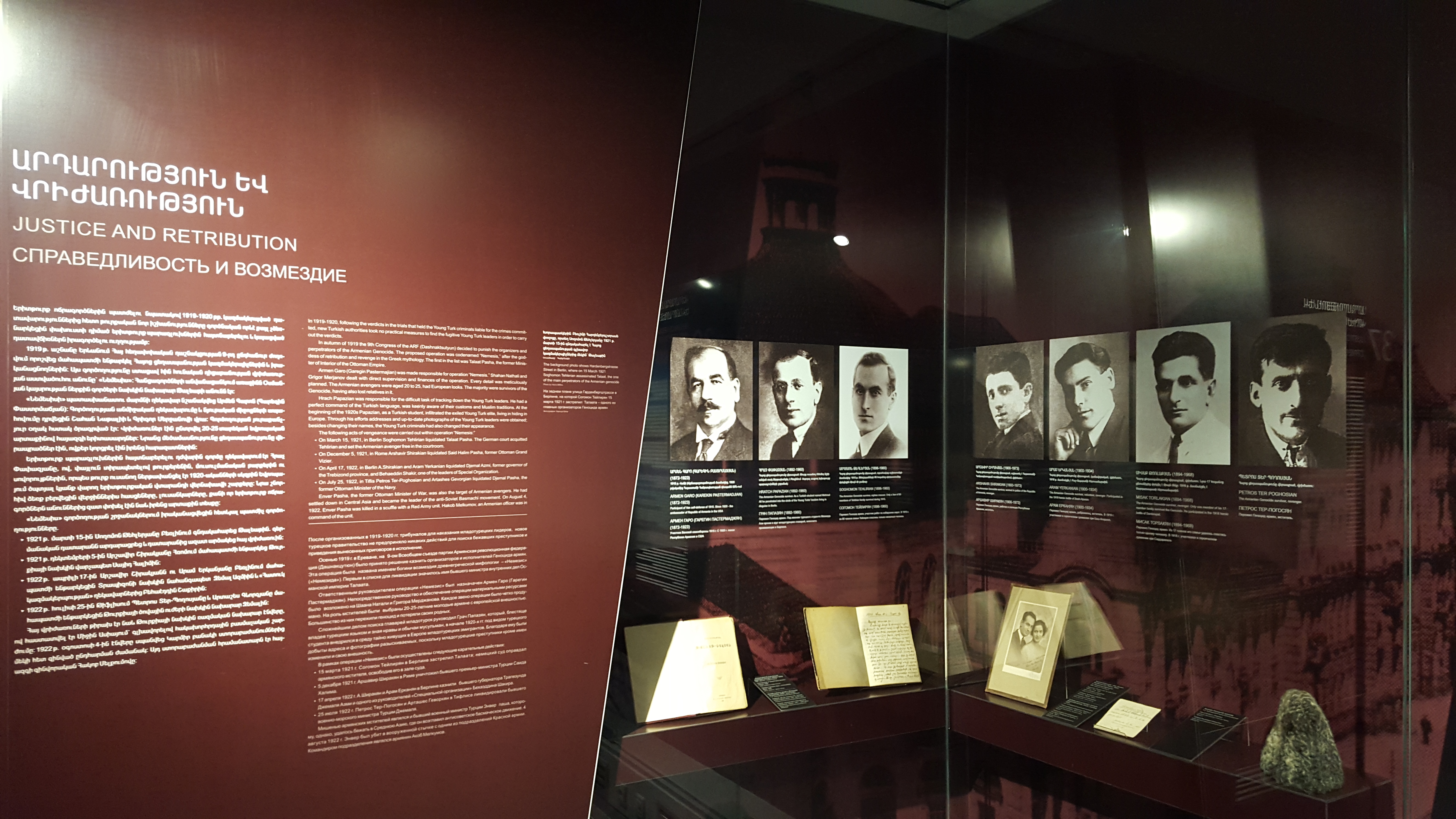

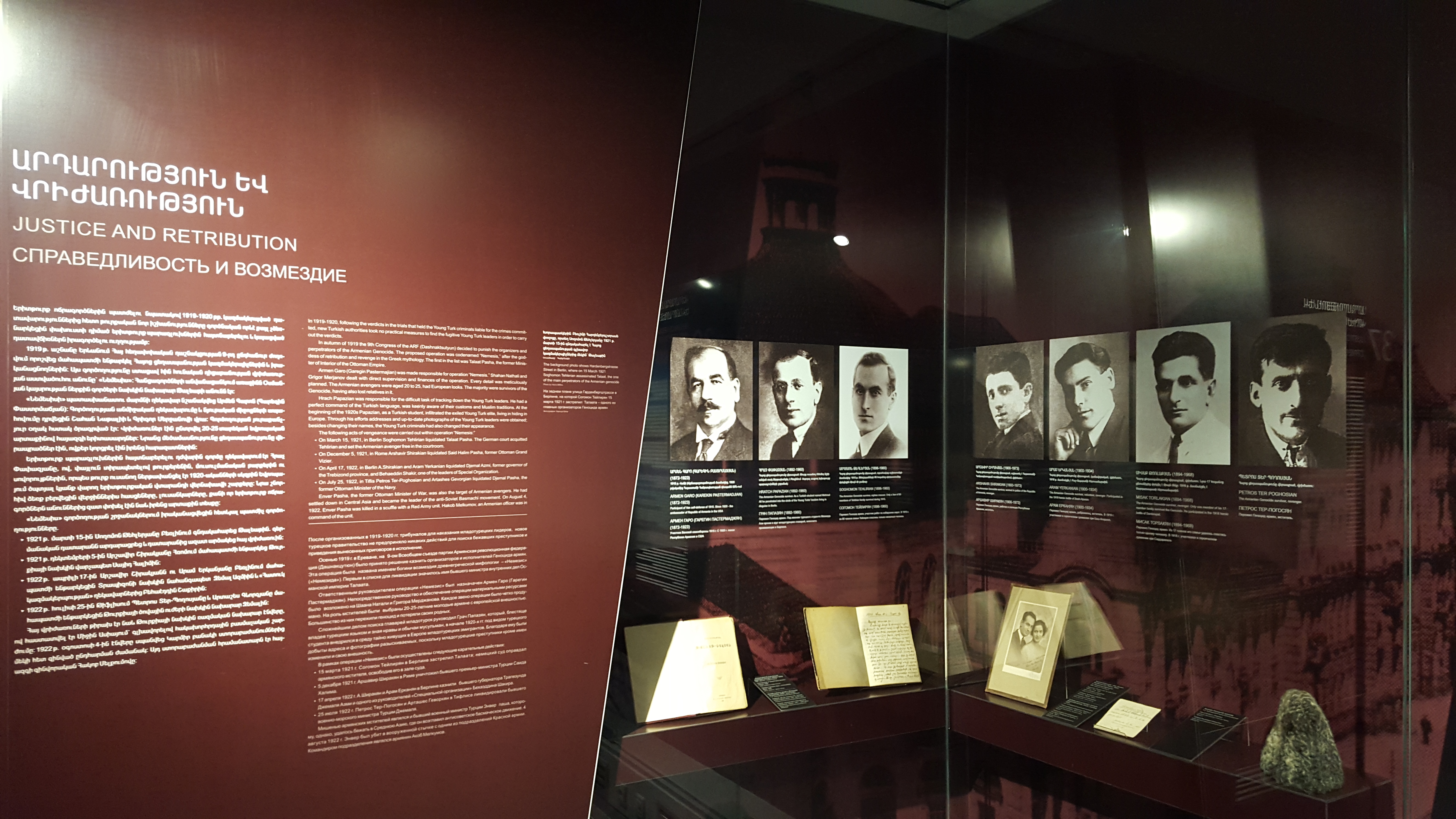

Since there were no international laws in place under which they could be tried, the men who orchestrated the massacres escaped prosecution and traveled relatively freely throughout Germany, Italy, and Central Asia. Power, Samantha. " A Problem from Hell", p. 16-17. Basic Books, 2002. That led to the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (, abbr. ARF (ՀՅԴ) or ARF-D), also known as Dashnaktsutyun (Armenians, Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Literal translation, lit. "Federation"), is an Armenian nationalism, Armenian nationalist a ...

's launch of Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis () was a program of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation to assassinate both Ottoman Empire, Ottoman perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and officials of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic most responsible for the massacre o ...

, a covert operation conducted by Armenians during which Ottoman political and military figures who fled prosecution were assassinated for their role in the Armenian genocide.

The Turkish courts-martial were forced to shut down during the resurgence of the Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement (), also known as the Anatolian Movement (), the Nationalist Movement (), and the Kemalists (, ''Kemalciler'' or ''Kemalistler''), included political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resu ...

under Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa () is one of the names of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Moustafa

* Moustafa A ...

. Those who remained serving their sentences were ultimately pardoned under the newly-established Kemalist government on 31 March 1923.

Background

World War I

Following the reportage by US Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau, Sr. of the Armenian resistance during the Armenian genocide at the city of Van, theTriple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

formally warned the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

on 24 May 1915 that:

In the months leading up to the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Ottoman Empire had undergone major restructuring. In July 1918, Sultan Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

died and was succeeded by his half-brother Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

. The Ministers of the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

(CUP), including the Three Pashas

The Three Pashas, also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate, consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha, the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha, the Minister of War and Commander-in-Chief to ...

who ran the Ottoman Government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were ...

between 1913 and 1918, had resigned from office and fled the country soon afterwards. Successful Allied offensives in Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

posed a direct threat to the Ottoman capital of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

.Findley, Carter Vaughn. ''Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity''. Yale University Press, 2010, p. 215 Sultan Mehmed VI appointed Ahmed Izzet Pasha

Ahmed Izzet Pasha (1864 – 31 March 1937 Ottoman Turkish: احمد عزت پاشا), known as Ahmet İzzet Furgaç after the Turkish Surname Law of 1934, was a Turkish-Albanian soldier and statesman. He was a general during World War I and al ...

to the position of Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

and tasked him with the assignment of seeking an armistice with the Allied Powers and ending Ottoman involvement in the war.Lewis, Bernard. ''The Emergence of Modern Turkey''. Oxford University Press, 1968, p.239

On 30 October 1918, an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

was signed between the Ottomans, represented by the Minister of the Navy Rauf Orbay

Hüseyin Rauf Orbay (27 July 1881 – 16 July 1964) was a Turkish naval officer, statesman and diplomat of Abkhaz origin. During the Italo–Turkish and Balkan Wars he was known as the Hero of '' Hamidiye'' for his exploits as captain of the e ...

, and the Allies, represented by British Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe (23 December 1864 – 27 July 1937), sometimes known as Sir Somerset Calthorpe, was a Royal Navy officer and a member of the Gough-Calthorpe family. After serving as a junior officer duri ...

. The armistice essentially ended Ottoman participation in the war and required the Empire's forces to stand down although there still remained approximately one million soldiers in the field and small scale fighting continued in the frontier provinces into November 1918.

Surrender of Constantinople

In November 1918, Britain appointed Admiral SirSomerset Gough-Calthorpe

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe (23 December 1864 – 27 July 1937), sometimes known as Sir Somerset Calthorpe, was a Royal Navy officer and a member of the Gough-Calthorpe family. After serving as a junior officer duri ...

as High Commissioner and Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Richard Webb as Assistant High Commissioner in Constantinople. A French brigade later entered Constantinople on 12 November 1918, and British troops first entered the city on 13 November 1918. Early in December in 1918, Allied troops occupied sections of Constantinople and set up a military administration.

The US Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. As Counselor to the State Department and then a ...

summoned the representatives of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

and Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha

" Damat" Mehmed Adil Ferid Pasha ( ; 1853 – 6 October 1923), known simply as Damat Ferid Pasha, was an Ottoman liberal statesman, who held the office of Grand Vizier, the ''de facto'' prime minister of the Ottoman Empire, during two ...

(a founding member of the Freedom and Accord Party

The Freedom and Accord Party (, French: ''Entente Libérale'') was a liberal Ottoman political party active between 1911–1913 and 1918–1919, during the Second Constitutional Era. It was the most significant opposition to Committee of Union a ...

). The Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

established "The Commission on Responsibilities and Sanctions" in January 1919.

On 2 January 1919, Gough-Calthorpe requested from the Foreign Office authority to obtain the arrest and handing over of all those responsible for the incessant breaches of the terms of the Armistice and the continued ill-treatment of Armenians. Calthorpe got together a staff of dedicated assistants, including a notable anti-Turkish Irishman, Andrew Ryan, later Sir, who in 1951 published his memoirs. In his new role as the chief Dragoman

A dragoman was an Interpreter (communication), interpreter, translator, and official guide between Turkish language, Turkish-, Arabic language, Arabic-, and Persian language, Persian-speaking countries and polity, polities of the Middle East and ...

of the British High Commission

A British High Commission is a British diplomatic mission, equivalent to an embassy, found in countries that are members of the Commonwealth of Nations. Their general purpose is to provide diplomatic relationships as well as travel information, ...

and Second Political Officer, he found himself in charge of the ''Armenian question''. He proved instrumental in the arrest of a large number of the (later to be) Malta deportees. These fell broadly into three categories: Those still breaching the terms of the armistice, those who had allegedly ill-treated Allied prisoners-of-war and those responsible for excesses against Armenians, in Turkey itself and the Caucasus. Calthorpe asked for a personal interview with Reshid Pasha, Ottoman Minister of Foreign Affairs, to impress on him how Britain viewed the Armenian affair and the ill-treatment of POWs as "most important" deserving "the utmost attention". Two days later Calthorpe formally requested the arrest of seven leaders of the CUP. While between 160 and 200 people were arrested, another 60 suspected of participating in the massacre of Armenians remained at large.Turkey’s EU Minister, Judge Giovanni Bonello And the Armenian Genocide – 'Claim about Malta Trials is nonsense'.

The Malta Independent

''The Malta Independent'' is a national newspaper published daily in Malta. It was started in 1992. The paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, ra ...

. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013

Courts-martial

Establishment

The courts-martial were established on 28 April 1919 while the

The courts-martial were established on 28 April 1919 while the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

was ongoing. An inquiry commission was established, called the "Mazhar Inquiry Commission", which was invested with extraordinary powers of subpoena, arrest, et cetera, through which the war criminals were summoned to trial. This organization secured Ottoman documents from many provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmet VI and Damat Ferid Pasha, as representatives of the Ottoman Empire were summoned to the Paris Peace Conference. On 11 July 1919, Ferid Pasha officially confessed to massacres against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire

Armenians were a significant minority in the Ottoman Empire. They belonged to either the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Catholic Church, or the Armenian Protestant Church, each church serving as the basis of a millet. They played a ...

and was a key figure and initiator of the war crime trials held directly after World War I to condemn to death the chief perpetrators of the genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

.

The Ottoman Government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were ...

in Constantinople (represented by Ferid Pasha), foisted the blame on a few members of the CUP and long-time rivals of his own Freedom and Accord Party

The Freedom and Accord Party (, French: ''Entente Libérale'') was a liberal Ottoman political party active between 1911–1913 and 1918–1919, during the Second Constitutional Era. It was the most significant opposition to Committee of Union a ...

, which would ensure that the Ottoman Empire received a more lenient treatment during the Paris Peace Conference. The trials helped the Freedom and Accord Party root out the CUP from the political arena. On 23 July 1919, during the Erzurum Congress

Erzurum Congress () was an assembly of Turkish Revolutionaries held from 23 July to 4 August 1919 in the city of Erzurum, in eastern Turkey, in accordance with the previously issued Amasya Circular. The congress united delegates from six easter ...

, General Kâzım Karabekir

Musa Kâzım Karabekir (also Kazim or Kiazim in English; 1882 – 26 January 1948) was a Turkish people, Turkish general and politician. He was the commander of the Eastern Front (Turkey), Eastern Army of the Ottoman Empire during the Turkish Wa ...

was issued a direct order from the Sultanate to place Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) and Rauf (Orbay) under arrest and assume Kemal's position as Inspector-General of the Eastern Provinces. He defied the government in Constantinople and refused to carry out the arrest.

At that time Turkey had two competing governments in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

and Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

. The government in Istanbul supported the Turkish trials with more or less seriousness depending on the current government. While Ferid Pasha (4 March – 2 October 1919 and again 5 April – 21 October 1920) stood behind the prosecuting body, the government of Ali Riza Pasha (2 October 1919 – 2 March 1920) barely made a mention of the legal proceedings against the war criminals. The trials had also blurred the crime of participation in the Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement (), also known as the Anatolian Movement (), the Nationalist Movement (), and the Kemalists (, ''Kemalciler'' or ''Kemalistler''), included political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resu ...

with the crime of the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

, and ultimately resulted in increasing support for the government in Ankara that would be led later on by Atatürk.

Procedure

The court sat for nearly a year, from April 1919 through March 1920, although it became clear after just a few months that the tribunal was simply going through the motions. The judges had condemned the first set of defendants (Enver, et al.) when they were safely out of the country, but the Tribunal, despite making a great show of its efforts, had no intention of returning convictions. Admiral Gough-Calthorpe protested to theSublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

, took the trials out of Turkish hands, and moved the proceedings to Malta. There an attempt was made to seat an international tribunal, but the Turks bungled the investigations and mishandled the documentary evidence so that nothing of their work could be used by the international court.Shadow of the Sultan's Realm: The Destruction of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, Daniel Allen Butler, Potomac Books Inc, 2011, , p.211-212

According to European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

judge Giovanni Bonello

Giovanni Bonello (born 11 June 1936 in Floriana) is a Maltese judge, judge of the European Court of Human Rights from 1998 until 2004, then extended till 2010.

Biography

His father, Vincenzo Bonello, was the curator of the national art colle ...

, 'quite likely the British found the continental inquisitorial system

An inquisitorial system is a legal system in which the court, or a part of the court, is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case. This is distinct from an adversarial system, in which the role of the court is primarily that of an ...

of penal procedure used in Turkey ''repugnant'' to its own paths to criminal justice and doubted the propriety of relying on it'. Or, possibly, the Turkish government never came round to hand over the incriminating documents used by the military courts. Whatever the reason, with the advent of power of Atatürk, all the documents on which the Turkish military courts had based their trials and convictions, were 'lost'. Admiral John de Robeck

Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Michael de Robeck, 1st Baronet, (10 June 1862 – 20 January 1928) was an officer in the Royal Navy. In the early years of the 20th century he served as Admiral of Patrols, commanding four flotillas of destroyers.

...

replaced Admiral Gough-Calthorpe on 5 August 1919 as "Commander in Chief, Mediterranean, and High Commissioner, at Constantinople". In August 1920, the proceedings were halted, and Admiral John de Robeck informed London of the futility of continuing the tribunal with the remark: "Its findings cannot be held of any account at all."Public Record Office, Foreign Office, 371/4174/136069 in

An investigative committee started by Hasan Mazhar was immediately tasked to gather evidence and testimonies, with a special effort to obtain inquiries on civil servants implicated in massacres committed against Armenians. According to genocide scholar Vahakn Dadrian

Vahakn Norair Dadrian (; 26 May 1926 – 2 August 2019) was an Armenian- American sociologist and historian, born in Turkey, professor of sociology, historian, and an expert on the Armenian genocide.

Life

Dadrian was born in 1926 in Turkey to ...

, the Commission worked in accordance with sections 47, 75 and 87 of the Ottoman Code of Criminal Procedure. It had extensive investigative powers, because it was not only limited to conduct legal proceedings and search for and seize documents, but also to arrest and imprison suspects with assistance from the Criminal Investigation Department, and other State services. In a course of three months, the committee managed to gather 130 documents and files pertaining to the massacres, and had them transferred to the courts-martial.

Turkish courts-martial also had some cases of high-ranking Ottoman officials, who were assassinated by agents of the CUP in 1915, for disobeying criminal orders of the central government to deport and eliminate the Armenian civilian population of the Ottoman Empire.

Verdicts

On 8 April 1919, Mehmed Kemal, formerKaymakam

Kaymakam, also known by #Names, many other romanizations, was a title used by various officials of the Ottoman Empire, including acting grand viziers, governors of provincial sanjaks, and administrators of district kazas. The title has been reta ...

of Boğazlıyan

Boğazlıyan is a town in Yozgat Province in the Central Anatolia region of Turkey. It is the seat of Boğazlıyan District.Yozgat

Yozgat is a city in the Central Anatolia Region of Turkey. It is the seat of Yozgat Province and Yozgat District. Prior to their executions, every condemned individual received a

fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

issued by the Shaykh al-Islam

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning " elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim scholar. Though this title generally refers to men, there are also a small number of ...

in the name of Mehmed VI, in accordance with the legal requirement that no Muslim could be put to death without such a decree from the Sultan-Caliph.

These legal proceedings and accompanying fatwas also functioned as vehicles for Mehmed VI to manifest his dissent towards the condemned individuals and justify his position, both within the context of his domestic affairs concerning the Muslim population within his empire and in response to the Western powers that had emerged victorious in World War I.

Abdullah Avni, the commander of the gendarmerie in Erzincan was sentenced to death during the Erzincan trials and hanged on 22 April 1920.

Behramzade Nusret, the Kaymakam of Bayburt

Bayburt () is a city in northeast Turkey lying on the Çoruh River. It is the seat of Bayburt Province and Bayburt District.

On 5 July 1919, the court reached a verdict which sentenced the organizers of the massacres, Talat, Enver, Cemal and others to death. The military court found that it was the intent of the CUP to eliminate the Armenians physically, via its Special Organization. The pronouncement reads as follows:

The courts-martial officially disbanded the CUP and confiscated its assets and the assets of those found guilty. Two of the three Pashas who fled were later assassinated by Armenian vigilantes during

At the

At the

Verdict of the Courts-Martial (In Ottoman Turkish)

Names of those condemned (In Ottoman Turkish)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919-1920 Aftermath of the Armenian genocide Greek genocide 1919 in the Ottoman Empire 1920 in the Ottoman Empire 1919 in law 1920 in law Aftermath of World War I in Turkey Ottoman Empire in World War I Trials of political people Court-martial cases World War I war crimes trials

Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis () was a program of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation to assassinate both Ottoman Empire, Ottoman perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and officials of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic most responsible for the massacre o ...

.

Detention in Malta and aftermath

Ottoman military members and high-ranking politicians convicted by the Turkish courts-martial were transferred from Constantinople prisons to theCrown Colony of Malta

The Crown Colony of the Island of Malta and its Dependencies (commonly known as the Crown Colony of Malta or simply Malta) was the British colony in the Maltese islands, that has become the modern Republic of Malta. It was established when the ...

on board of the SS ''Princess Ena'' and the SS HMS ''Benbow'' by the British forces, starting in 1919. Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe was in charge of the operation, together with Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

; they did so owing to the lack of transparency of the Turkish courts-martial. They were held there for three years, while searches were made of archives in Constantinople, London, Paris and Washington to find a way to put them in trial. However, the war criminals were eventually released without trial and returned to Constantinople in 1921, in exchange for 22 British prisoners of war held by the government in Ankara, including a relative of Lord Curzon. The government in Ankara was opposed to political power of the government in Constantinople. They are often mentioned as the ''Malta exiles

The Malta exiles () were the purges of Ottoman intellectuals by the Allied forces. The exile to Malta occurred between March 1919 and October 1920 of politicians, high ranking soldiers (mainly), administrators and intellectuals of the Ottoman Empir ...

'' in some sources.

According to European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

judge Giovanni Bonello

Giovanni Bonello (born 11 June 1936 in Floriana) is a Maltese judge, judge of the European Court of Human Rights from 1998 until 2004, then extended till 2010.

Biography

His father, Vincenzo Bonello, was the curator of the national art colle ...

the suspension of prosecutions, the repatriation and release of Turkish detainees was amongst others a result of the lack of an appropriate legal framework with supranational jurisdiction, because following World War I no international norms for regulating war crimes existed, due to a legal vacuum in international law; therefore contrary to Turkish sources, no trials were ever held in Malta. He mentions that the release of the Turkish detainees was accomplished in exchange for 22 British prisoners held by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Punishment

At the

At the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (, abbr. ARF (ՀՅԴ) or ARF-D), also known as Dashnaktsutyun (Armenians, Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Literal translation, lit. "Federation"), is an Armenian nationalism, Armenian nationalist a ...

's 9th General Congress, which convened in Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , ; ; sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia, as well as one of the world's List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerev ...

from 27 September, to the end of October 1919, the issue of retribution against those personally responsible for organizing the genocide was on the agenda. A task force, led by Shahan Natalie

Shahan Natalie (; July 14, 1884 – April 19, 1983) was an Armenian writer and political activist who was the principal organizer of Operation Nemesis, a campaign of revenge against officials of the former Ottoman Empire who organized the Armen ...

, working with Grigor Merjanov, was established to assassinate Talaat Pasha

Mehmed Talât (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha, was an Ottoman Young Turk activist, revolutionary, politician, and convicted war criminal who served as the leader of the Ottoman Empire from 191 ...

, Javanshir Khan, Said Halim Pasha

Mehmed Said Halim Pasha (; ; 18 or 28 January 1865 or 19 February 1864 – 6 December 1921) was a writer and statesman who served as the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1917. He was one of the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide ...

, Behaeddin Shakir Bey, Jemal Azmi, Cemal Pasha

Ahmed Djemal (; ; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), also known as Djemal Pasha or Cemâl Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one of the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

As an officer of the II Corps, he was ...

, Enver Pasha

İsmâil Enver (; ; 23 November 1881 – 4 August 1922), better known as Enver Pasha, was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Turkish people, Turkish military officer, revolutionary, and Istanbul trials of 1919–1920, convicted war criminal who was a p ...

, as well as several Armenian collaborators, in a secret operation codenamed Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis () was a program of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation to assassinate both Ottoman Empire, Ottoman perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and officials of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic most responsible for the massacre o ...

.

Purging of evidence

According to a leaked diplomatic cable from 2004, ambassador Muharrem Nuri Birgi was effectively in charge of destroying evidence during the 1980s. During the process of eliminating the evidence, ambassador Birgi stated in reference to the Armenians: "We really slaughtered them." Others, such as Tony Greenwood, the Director of the American Research Institute in Turkey, confirmed that a select group of retired military personnel were "going through" the archives. However, it was noted by a certain Turkish scholar that the examination was merely an effort to purge documents found in the archives.Controversy

Those who deny the Armenian genocide have questioned the translations into Western language (mostly English and German) of the verdicts and accounts published in newspapers. Gilles Veinstein, a professor of Ottoman and Turkish history atCollège de France

The (), formerly known as the or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment () in France. It is located in Paris near La Sorbonne. The has been considered to be France's most ...

estimates that the translation made by former Armenian historian Haigazn Kazarian is "highly tendentious, in several locations". Turkish historians Erman Şahin and Ferudun Ata accuse Taner Akçam of mistranslations and inaccurate summaries, including the rewriting of important sentences and the addition of things not included in the original version.Ferudun Ata, "An Evaluation of the Approach of the Researchers Who Advocate Armenian Genocide to the Trials Relocation," in ''The New Approaches to Turkish-Armenian Relations'', Istanbul, Istanbul University Publications, 2008, pp. 560–561.

See also

*Mustafa Yamulki

Mustafa Yamulki (25 January 1866 – 25 May 1936), also known as "Nemrud" Mustafa Pasha, was a Ottoman - Kurdish military officer, chairman of the Ottoman military court, minister for education in the Kingdom of Kurdistan and a journalist. Mustaf ...

* Outline and timeline of the Greek genocide

* Turkish war crimes

Since the foundation of the Turkey, Republic of Turkey, its Turkish Armed Forces, official armed and Paramilitary, paramilitary forces have committed numerous violations of international criminal law (including war crimes, crimes against humanity ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

Verdict of the Courts-Martial (In Ottoman Turkish)

Names of those condemned (In Ottoman Turkish)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919-1920 Aftermath of the Armenian genocide Greek genocide 1919 in the Ottoman Empire 1920 in the Ottoman Empire 1919 in law 1920 in law Aftermath of World War I in Turkey Ottoman Empire in World War I Trials of political people Court-martial cases World War I war crimes trials