In

linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, inalienable possession (

abbreviated ) is a type of

possession in which a

noun

In grammar, a noun is a word that represents a concrete or abstract thing, like living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, and ideas. A noun may serve as an Object (grammar), object or Subject (grammar), subject within a p ...

is

obligatorily possessed by its possessor. Nouns or

nominal affixes in an inalienable possession relationship cannot exist independently or be "alienated" from their possessor.

Inalienable nouns include body parts (such as ''leg'', which is necessarily "someone's leg" even if it is severed from the body),

kinship terms (such as ''mother''), and part-whole relations (such as ''top'').

Many languages reflect the distinction but vary in how they mark inalienable possession.

[ Cross-linguistically, inalienability correlates with many morphological, syntactic, and ]semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

properties.

In general, the alienable–inalienable distinction is an example of a binary possessive class system

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

in which a language distinguishes two kinds of possession (alienable and inalienable). The alienability distinction is the most common kind of binary possessive class system, but it is not the only one.Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an island country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean n ...

, for example, Anêm has at least 20 classes, and Amele has 32.[

Statistically, 15–20% of the world's languages have obligatory possession.]

Comparison to alienable possession

With inalienable possession, the two entities have a permanent association in which the possessed has little control over their possessor.

Variation by languages

Although the relationships listed above are likely to be instances of inalienable possession, those that are ultimately classified as inalienable depend on conventions that are specific by language and culture.[ Additionally, in some languages, one entity can be both alienably possessed and inalienably possessed, and its type of possession is influenced by other properties of the sentence.]grammatical gender

In linguistics, a grammatical gender system is a specific form of a noun class system, where nouns are assigned to gender categories that are often not related to the real-world qualities of the entities denoted by those nouns. In languages wit ...

.

The examples below illustrate that the same phrase, ''the table's legs'', is regarded as inalienable possession in Italian but alienable possession in French:language change

Language change is the process of alteration in the features of a single language, or of languages in general, over time. It is studied in several subfields of linguistics: historical linguistics, sociolinguistics, and evolutionary linguistic ...

is responsible for the observed cross-linguistic variation in the categorization of (in)alienable nouns. He states that "rather than being a semantically defined category, inalienability is more likely to constitute a morphosyntactic or morphophonological entity, one that owes its existence to the fact that certain nouns happened to be left out when a new pattern for marking attributive possession arose."

Morphosyntactic strategies for marking distinction

The distinction between alienable and inalienable possession is often marked by various morphosyntactic properties such as morphological markers and word order. The morphosyntactic differences are often referred to as possession split or split possession, which refer to instances of a language making a grammatical distinction between different types of possession.determiner phrase

In linguistics, a determiner phrase (DP) is a type of phrase headed by a determiner such as ''many''. Controversially, many approaches take a phrase like ''not very many apples'' to be a DP, Head (linguistics), headed, in this case, by the determin ...

(DP), in which the possessor nominal may occur either before the possessee (prenominal) or after its possessee (postnominal), depending on the language.

In contrast, English generally uses a prenominal possessor (''Johns brother''). However, in some situations, it may also use a postnominal possessor, as in ''the brother of John''.

In contrast, English generally uses a prenominal possessor (''Johns brother''). However, in some situations, it may also use a postnominal possessor, as in ''the brother of John''.[

]

Morphological markers

No overt possessive markers

The South American language

The languages of South America can be divided into three broad groups:

* the languages of the (in most cases, former) colonial powers, primarily Spanish and Portuguese;

* many indigenous languages, some of which are co-official alongside t ...

Dâw uses a special possessive morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

(bold in the examples below) to indicate alienable possession.

Identical possessor deletion

In Igbo, a West African language, the possessor is deleted in a sentence if both its subject and the possessor of an inalienable noun refer to the same entity.Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

, notably Serbian:

Word order

Possessor switch

The distinction between alienable and inalienable possession constructions may be marked by a difference in word order. Igbo uses another syntactic process when the subject and the possessor refer to different entities.[ In possessor switch, the possessor of the inalienable noun is placed as close as possible to the ]verb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

.[ In the following examples, the possessor ''yá'' is not deleted because both referents are different:

In the ungrammatical (8a), the verb ''wàra'' (''to split'') follows the possessor ''m''. Possessor switch requires the verb to be placed nearer to the possessor. The grammatical (8b) does so switching ''wàra'' with the possessor:

]

Genitive-noun ordering

The Maybrat languages in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

vary the order of the genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive ca ...

and the noun between alienable and inalienable constructions:

Possessor marking

Explicit possessors

Another way for languages to distinguish between alienable and inalienable possession is to have one noun class that cannot appear without an explicit possessor.Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

, an Algonquian language, has a class of nouns that must have explicit possessors.[Valentine, J. Randolph ''Nishnaabemwin Reference Grammar Nishnaabemwin Reference Grammar.'' Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2001. §3.3.1. pg. 106 ff.][Nichols, J. D.; Nyholm, E. ''A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.'' 1995.]

If explicit possessors are absent (as in (11b) and (12b)), the phrase is ungrammatical. In (11), the possessor ''ni'' is necessary for the inalienable noun ''nik'' (''arm''). In (12), the same phenomenon is found with the inalienable noun ''ookmis'' (''grandmother''), which requires the possessor morpheme ''n'' to be grammatical.

Prepositions

Hawaiian uses different prepositions to mark possession, depending on the noun's alienability: ''a'' (alienable ''of'') is used to indicate alienable possession as in (13a), and ''o'' (inalienable ''of'') indicates inalienable possession as in (13b).semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

distinctions that are less clearly attributable to common alienability relationships except metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

ically. Although ''lei'' is a tangible object, but in Hawaiian, it can be either alienable (15a) or inalienable (15b), depending on the context.

Definite articles

Subtler cases of syntactic patterns sensitive to alienability are found in many languages. For example, French can use a definite article

In grammar, an article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" ...

, rather than the possessive, for body parts.ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning (linguistics), meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A com ...

. Thus, the sentence has both an alienable and an inalienable interpretation:

Such an ambiguity also occurs in English with body-part constructions.[

]

No distinction in grammar

Although English has alienable and inalienable nouns (''Mary's brother'' nalienablevs. ''Mary's squirrel'' lienable, it has few such formal distinctions in its grammar.[ Sentence (20) is ambiguous and has two possible meanings. In the inalienable possessive interpretation, ''la main'' belongs to the subject, ''les enfants''. The second interpretation is that ''la main'' is an alienable object and does not belong to the subject. The English equivalent of the sentence (''The children raised the hand'') has only the alienable possessive reading in which the hand does not belong to the children.

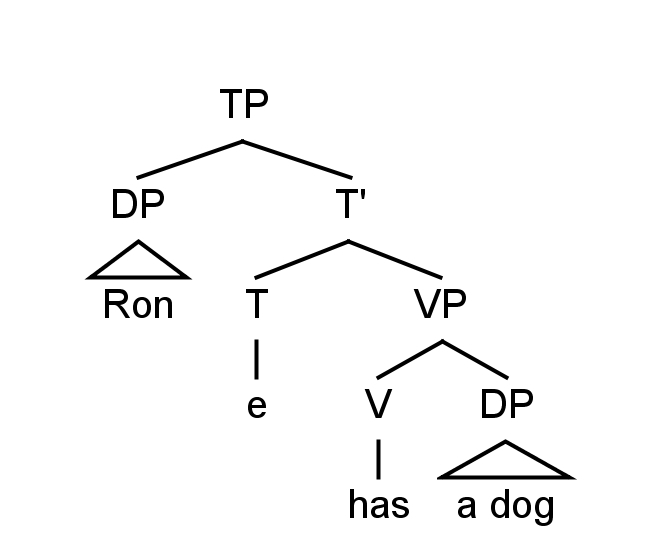

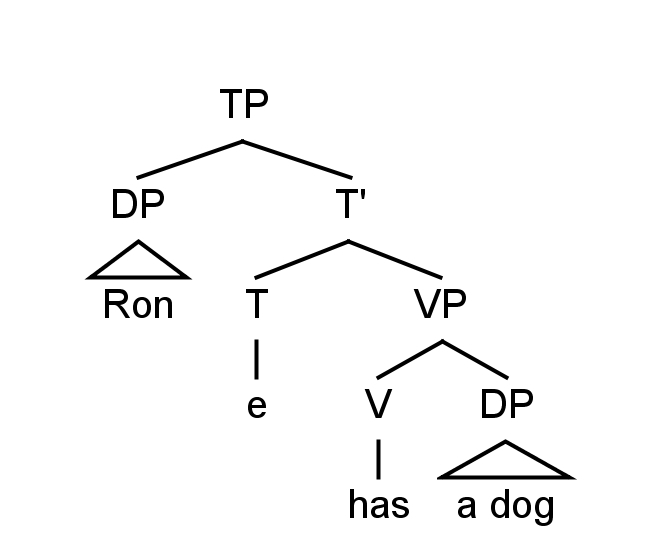

Syntactically, ]Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

proposed that some genitive or possessive cases originate as part of the determiner

Determiner, also called determinative ( abbreviated ), is a term used in some models of grammatical description to describe a word or affix belonging to a class of noun modifiers. A determiner combines with a noun to express its reference. Examp ...

in the underlying structure.phrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

''John's arm'':

In the inalienable reading, ''arm'' is a complement of the determiner phrase. That contrasts to the alienable reading in which ''John has an arm'' is part of the determiner.[ Charles J. Fillmore and Chomsky make a syntactic distinction between alienable and inalienable possession and suggest that the distinction is relevant to English.][

In contrast, others have argued that semantics plays a role in inalienable possession, but it is not central to the syntactic class of case-derived possessives. An example is the difference between ''the book's contents'' and ''the book's jacket''. A book cannot be divorced from its contents, but it can be removed from its jacket.][ Still, both phrases have the same syntactic structure. Another example is ''Mary's mother'' and ''Mary's friend''. The mother will always be Mary's mother, but an individual might not always be Mary's friend. Again, both have the same syntactic structure.

The distinction between alienable and inalienable possessions can be influenced by cognitive factors.]

Interaction with coreference

There are few grammatical distinctions between alienable and inalienable possession in English, but there are differences in the way coreference occurs for such possessive constructions. For instance, examples (21a) and (21b) have interpretations that differ by the type of (in)alienable possession:

In example (1a), the pronominal possessor (''her'') can refer to ''Lucy'' or to another possessor not mentioned in the sentence. As such, two interpretations of the sentence are possible:

However, in example (21b), the pronominal possessor (''her'') can only grammatically refer to Lucy. As such, the hand being discussed must belong to Lucy.

Therefore, the pronominal possessor patterns with pronominal binding in the alienable construction, but the pronominal possessor patterns with anaphoric binding in the inalienable construction.

Therefore, the pronominal possessor patterns with pronominal binding in the alienable construction, but the pronominal possessor patterns with anaphoric binding in the inalienable construction.

Cross-linguistic properties

Although there are different methods of marking inalienability, inalienable possession constructions usually involve the following features:[

* The distinction is confined to attributive possession.

* Alienable possession requires more phonological or morphological features than inalienable possession.

*Inalienable possession involves a tighter structural bond between the possessor and the possessee.

* Possessive markers on inalienable nouns are etymologically older

* Inalienable nouns include kinship terms and/or body parts.

* Inalienable nouns form a closed class, but alienable nouns form an open class.

(Heine 1997: 85-86 (1-6))

]

Restricted to attributive possession

Alienability can be expressed only in attributive possession constructions, not in predicative possession.

Alienability can be expressed only in attributive possession constructions, not in predicative possession.[

Attributive possession is a type of possession in which the possessor and possessee form a ]phrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

. That contrasts to predicative possession constructions in which the possessor and possessee are part of a clause

In language, a clause is a Constituent (linguistics), constituent or Phrase (grammar), phrase that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic Predicate (grammar), predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject (grammar), ...

, and the verb affirms the possessive relationship.

Requires fewer morphological features

If a language has separate alienable and inalienable possession constructions, and one of the constructions is overtly marked and the other is "zero-marked", the marked form tends to be alienable possession. Inalienable possession is indicated by the absence of the overt marker.

Tighter structural bond between possessor and possessee

In inalienable possession constructions, the relationship between the possessor and possessee is stronger than in alienable possession constructions. Johanna Nichols characterizes that by the tendency of inalienable possession to be head-marked but alienable possession to be dependent-marked.head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

of an inalienable possession construction (the possessed noun) is marked, but in dependent-marking, the dependent (the possessor noun) is marked.

Theories of representation in syntax

Since the possessor is crucially linked to an inalienable noun's meaning, inalienable nouns are assumed to take their possessors as a semantic argument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

.genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive ca ...

like ''the friend of Mary'' appear as complements to the possessed noun, as part of the phrase headed by the inalienable noun.[ That is an example of internal possession since the possessor of the noun is inside the determiner phrase.

]

External possession

Inalienable possession can also be marked with external possession. Such constructions have the possessor appearing outside the determiner phrase. For example, the possessor may appear as a dative complement of the verb.

French exhibits both external possessor construction and internal possessor construction, as in (23):

Inalienable possession can also be marked with external possession. Such constructions have the possessor appearing outside the determiner phrase. For example, the possessor may appear as a dative complement of the verb.

French exhibits both external possessor construction and internal possessor construction, as in (23):[

However, those types of possessors are problematic. There is a discrepancy between the possessor appearing syntactically in an inalienable possession construction and what its semantic relationship to the inalienable noun seems to be. Semantically, the possessor of an inalienable noun is intrinsic to its meaning and acts like a semantic argument. On the surface syntactic structure, however, the possessor appears in a position that marks it as an argument of the verb.]

Binding hypothesis (Guéron 1983)

The binding hypothesis reconciles the fact that the possessor appears both as a syntactic and semantic argument of the verb but as a semantic argument of the possessed noun. It assumes that inalienable possession constructions are subject to the following syntactic constraints:c-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, a node in a parse tree c-commands its sister node and all of its sister's descendants. In these frameworks, c-command plays a central role in defining and constraining operations such as syntactic movem ...

the possessee or its trace (The c-command must occur in the underlying or surface structures of the inalienable possession constructions.

It is assumed that inalienable possession constructions are one form of anaphoric binding: obligatory control.

It is assumed that inalienable possession constructions are one form of anaphoric binding: obligatory control.[

The hypothesis accounts for differences between French and English, and it may also eliminate the ambiguity created by definite determiners.]Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

and also Russian but not in English or Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

.

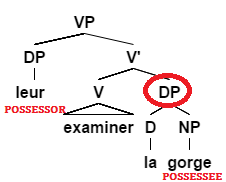

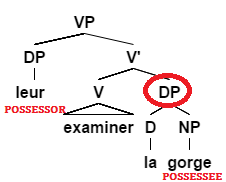

Possessor-raising hypothesis (Landau 1999)

Possessor-raising is a syntactic hypothesis that attempts to explain the structures of inalienable DPs. Landau argues that the possessor is initially introduced in the specifier position of DP (Spec-DP), but it later raises to the specifier of the VP. The possessor DP gets its theta-role from the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

D, which gives rise to the meaning that the possessor is related to the possessee.[

# The possessor dative must be interpreted as a possessor, not an object/theme.

# Possession interpretation is obligatory.

# The possessed DP cannot be an external argument.

# The possessor dative must c-command the possessed DP (or its trace).

# Possessive interpretation is constrained by locality. (Nakamoto 2010: 76)

] The French data below illustrate how the analysis is thought to work. The possessor ''lui'' originates in the specifier of DP as an argument of the noun ''figure''. That is equivalent to an underlying structure ''Gilles a lavé lui la figure''. The possessor raises to the specifier of VP, which is seen in the surface structure ''Gilles lui a lavé la figure''.

According to Guéron, a benefit of the hypothesis is that it is consistent with principles of syntactic movement such as locality of selection and

The French data below illustrate how the analysis is thought to work. The possessor ''lui'' originates in the specifier of DP as an argument of the noun ''figure''. That is equivalent to an underlying structure ''Gilles a lavé lui la figure''. The possessor raises to the specifier of VP, which is seen in the surface structure ''Gilles lui a lavé la figure''.

According to Guéron, a benefit of the hypothesis is that it is consistent with principles of syntactic movement such as locality of selection and c-command

In generative grammar and related frameworks, a node in a parse tree c-commands its sister node and all of its sister's descendants. In these frameworks, c-command plays a central role in defining and constraining operations such as syntactic movem ...

. If the position to which it must move is already filled, as with a transitive verb like ''see'', the possessor cannot raise, and the sentence is correctly predicted to be ungrammatical.

Possessor suppression with kin and body-part nouns (Lødrup 2014)

Norwegian is a North Germanic language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

that is spoken mainly in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and is its official language. Norwegian expresses inalienability by possessor suppression, which takes place when noun phrases referring to inalienable possessions use the definite form and contain no possessive determiner.

In sentence (28), "haken", the syntactic object, contains a suppressed possessor in its definite form. It does not contain an explicit possessive marker. In contrast, the English translation contains an explicit possessive determiner, "her", which denote possession. Possessive determiners are obligatory in English for subject-controlled body-part terms.

Norwegian treats kinship nouns and body-part nouns similarly in relation to bound variable interpretations. When a definite noun is present, it usually has a referential reading. In (29a), the referential reading is present. However, the presence of definite kinship or body part nouns may also bring about the bound variable reading in which a kinship or body part noun contains a variable bound by the quantifier in the subject, and (29b) may produce both the referential and bound variable readings. With the referential reading, the professors washed a face or father, mentioned earlier. With the bound variable reading, the professors washed their own face or father. Additionally, both kinship and body part nouns behave similarly in sentences with VP pronominalization. VP pronominalization involving both nouns allow for both a referential reading and a "sloppy reading", which involves variable binding. In (29c) in the referential reading, John and Mari wash a face or a mother been mentioned earlier. In the "sloppy reading", John washes his face or mother, and Mari washes hers.

Finally, both kinship and body part nouns bear similarities in locality. Both behave in such a way that the definite form of the noun is bound by the closest subject. In (30a), the possessor must be the subordinate clause subject, not the main clause subject. Likewise, in (30b), the father mentioned is preferably the father of the subordinate clause subject referent, not of the main clause subject referent.

Norwegian treats kinship nouns and body-part nouns similarly in relation to bound variable interpretations. When a definite noun is present, it usually has a referential reading. In (29a), the referential reading is present. However, the presence of definite kinship or body part nouns may also bring about the bound variable reading in which a kinship or body part noun contains a variable bound by the quantifier in the subject, and (29b) may produce both the referential and bound variable readings. With the referential reading, the professors washed a face or father, mentioned earlier. With the bound variable reading, the professors washed their own face or father. Additionally, both kinship and body part nouns behave similarly in sentences with VP pronominalization. VP pronominalization involving both nouns allow for both a referential reading and a "sloppy reading", which involves variable binding. In (29c) in the referential reading, John and Mari wash a face or a mother been mentioned earlier. In the "sloppy reading", John washes his face or mother, and Mari washes hers.

Finally, both kinship and body part nouns bear similarities in locality. Both behave in such a way that the definite form of the noun is bound by the closest subject. In (30a), the possessor must be the subordinate clause subject, not the main clause subject. Likewise, in (30b), the father mentioned is preferably the father of the subordinate clause subject referent, not of the main clause subject referent.

On the other hand, definite kinship and body-part nouns in Norwegian have a syntactic difference. Definite body part nouns allow a first- or second-person possessor, but some definite kinship nouns do not. For instance, the sentence in (31a) is not allowed as it contains a first-person possessor and kinship term. The kinship term can be used only with a third-person possessor, such as in (31b).

On the other hand, definite kinship and body-part nouns in Norwegian have a syntactic difference. Definite body part nouns allow a first- or second-person possessor, but some definite kinship nouns do not. For instance, the sentence in (31a) is not allowed as it contains a first-person possessor and kinship term. The kinship term can be used only with a third-person possessor, such as in (31b).

However, body part nouns do not have the restriction on first- or second-person possessors like in (32).

However, body part nouns do not have the restriction on first- or second-person possessors like in (32).

Form function motivations

Inalienable possession constructions often lack overt possessors.[ There is a debate as to how to account for the linguistically-universal difference in form. Iconicity explains the in terms of the relationship between the conceptual distance between the possessor and the possessee,]

Iconic motivation (Haiman 1983)

Haiman describes iconic expression and conceptual distance and how both concepts are conceptually close if they share semantic properties, affect each other and cannot be separated from each other.prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Particularly in the study of languages, a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the word to which it is affixed.

Prefixes, like other affixes, can b ...

ed on the possessee, as in (33b), a construction that has less linguistic distance between the possessor and possessee than the alienable construction has:

However, there are cases of linguistic distance not necessarily reflecting conceptual distance. Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin ( ; zh, s=, t=, p=Guānhuà, l=Mandarin (bureaucrat), officials' speech) is the largest branch of the Sinitic languages. Mandarin varieties are spoken by 70 percent of all Chinese speakers over a large geographical area that stretch ...

has two ways to express the same type of possession: POSSESSOR + POSSESSEE and POSSESSOR + de + POSSESSEE. The latter has more linguistic distance between the possessor and the possessee, but it reflects the same conceptual distance.

Economic motivation (Nichols 1988)

Nichols notes that frequently-possessed nouns, such as body parts and kinship terms, almost always occur with possessors, and alienable nouns occur less often with possessors.[ The table below shows the number of times that each noun occurred with or without a possessor in texts from the German Goethe-Corpus of the works of ]Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

.

The alienable nouns above are rarely possessed, but the inalienable kinship terms are frequently possessed.[ Consequently, inalienable nouns are expected to be possessed even if they lack a distinct possessive marker. Therefore, overt markings on inalienable nouns are redundant, and for economical syntactic construction, languages often have zero-marking for their inalienable nouns.][

]

Glossary of abbreviations

Morpheme glosses

Syntactic trees

D:determiner

DP:determiner phrase

N:noun

NP:noun phrase

PP:prepositional phrase

T:tense

TP:tense phrase

V:verb

VP:verb phrase

Other languages

Austronesian languages

Rapa

Old Rapa is the indigenous language of Rapa Iti, an island of French Polynesia

French Polynesia ( ; ; ) is an overseas collectivity of France and its sole #Governance, overseas country. It comprises 121 geographically dispersed islands and atolls stretching over more than in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. The t ...

in the Bass Islands archipelago. The language structure of Rapa has two primary possessive particles: a and o. The usage of both particles is dependent on the relation between the possessor and the object. When words are categorized by possessive particles, there is a very close resemblance to the usage of the possessive particle and the object's alienability. However, the relation is better defined by William Wilson in his article ''Proto-Polynesian Possessive Marking''.

Briefly, through his two theories, the Simple Control Theory and Initial Control Theory, Wilson contrasts and thus better defines the usage of the possessive particles. The Simple Control Theory speculates that the determining factor directly correlated to the possessor's control over the object and emphasises a dominant vs. less-dominant relationship. Old Rapa adheres closer to the Initial Control Theory, which speculates that "the possessor's control over the initiation of the possessive relationship is the determining factor." Here, the Initial Control Theory can also be generally expanded to the whole Polynesian language family in terms of better describing the "alienability" of possession.[WILSON, WILLIAM H. 1982. Proto-Polynesian possessive marking. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.]

In the case of Old Rapa, the possession particle o is used to define a possession relationship that was not initiated on the basis of choice. The possession particle a defines possession relationships that are initiated with the possessor's control. The following list and classifications are literal examples provided by Mary Walworth in her dissertation of Rapa. Words that are marked with the o possessive markers are nouns that are:

* Inalienable (leg, hand, foot)

* A whole of which the possessor is a permanent part (household)

* Kinship (father, mother, brother)

* Higher social or religious status (teacher, pastor, president)

* Vehicles (canoe, car)

* Necessary actions (work)

* Involuntary body functions (heartbeat, stomach, pupils, breathing)

* Words that relate to indigenous identity (language, country)

However, Wilson's theory falls short of properly categorizing a few miscellaneous items such as articles of clothing and furniture that his theory would incorrectly predict to be marked with the possessive particle a. The reverse occurs for objects such as food and animals. The synthesis of Wilson's theory and others approach a better understanding of the Rapa language. Svenja Völkel proposed the idea of looking further into the ritualistic beliefs of the community: its mana. That idea has been related to other languages in the Eastern Polynesian language family. It states that objects with less mana than the possessor use the a-possessive particle, and the usage of the o-possessive marker is reserved for the possessor's mana that is not superior.

The same usage of the possessive particles in possessive pronouns can be seen in the contracted portmanteau, the combination of the articles and possessive markers. The results are the prefixes tō and tā in the following possessive pronouns, as can be seen in the table below:

Wuvulu

Wuvulu language is a small language spoken in Wuvulu Island. Direct possession has a close relationship with inalienability in Oceanic linguistics. Similarly, the inherent possession of the possessor is called the possessum.

The inalienable noun also has a possessor suffix and includes body parts, kinship terms, locative part nouns and derived nouns. According to Hafford's research, "-u" (my), "-mu" (your) and "na-"(his/her/its) are three direct possession suffix in Wuvulu.

Tokelauan

Here is a table displaying the predicative possessive pronouns in Tokelauan language, Tokelauan:

{, class="wikitable"

, -

! colspan="2" ,

! Singular

! Dual

! Plural

, -

! rowspan="2" , 1st person

! incl.

, rowspan="2" , o oku, o kita

a aku, a kite

, o taua, o ta

a taua, a ta

, o tatou

a tatou

, -

! excl.

, o maua, o ma o

a maua, a ma a

, matou

matou

, -

! colspan="2" , 2nd person

, o ou/o koe

a au/a koe

, o koulua

a koulua

, o koutou

a koutou

, -

! colspan="2" , 3rd person

, o ona

a ona

, o laua, o la

a laua, a la

, o latou

a latou

ta ta, ta taue

, o ta, o taue

a ta, a taua

, -

! 1 dual excl.

, to ma, to maua

ta ma, ta maua

, o ma, o maua

a ma, a maua

, -

! 2 dual

, toulua, taulua

, oulua, aulua

, -

! 3 dual

, to la, to laue

ta la, ta laue

, o la, o laua

a la a laua

, -

! 1 plural incl.

, to tatou, ta tatou

, o tatou, a tatou

, -

! 1 plural excl.

, to matou, ta matou

, o matou, a matou

, -

! 2 plural

, toutou, tautau

, outou, autou

, -

! 3 plural

, to latou, ta latau

, o latou, a latou

, -

!

! colspan="2" , NON-SPECIFIC/INDEFINITE

, -

! 1 singular

, hoku, hota

haku, hata

, ni oku, ni ota

niaku, niata

, -

! 2 singular

, ho, hau

, ni o, ni au

, -

! 3 singular

, hona, hana

, ni ona, ni ana

, -

! 1 dual incl.

, ho ta, ho taua

ha ta, ha taua

, ni o ta, ni o taue

ni a ta, ni a taua

, -

! 1 dual excl.

, ho ma, ho maua

ha ma, ha maua

, ni o ma, ni o maua

ni a ma, ni a maua

, -

! 2 dual

, houlua, haulua

, ni oulua, ni aulua

See also

* Possession (linguistics)

* Obligatory possession

* Noun class

* Determiner phrase

In linguistics, a determiner phrase (DP) is a type of phrase headed by a determiner such as ''many''. Controversially, many approaches take a phrase like ''not very many apples'' to be a DP, Head (linguistics), headed, in this case, by the determin ...

* Noun phrase

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently ...

* Possessive

* Possessive affix

* English possessive

In English, possessive words or phrases exist for nouns and most pronouns, as well as some noun phrases. These can play the roles of determiners (also called possessive adjectives when corresponding to a pronoun) or of nouns.

For nouns, noun ph ...

* Genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive ca ...

Notes

References

External links

A map of the world's languages colored by possessive classification complexity

from the World Atlas of Language Structures.

{{Formal semantics

Grammatical categories

Grammar

Genitive construction

Grammatical construction types

Formal semantics (natural language)

In contrast, English generally uses a prenominal possessor (''Johns brother''). However, in some situations, it may also use a postnominal possessor, as in ''the brother of John''.

In contrast, English generally uses a prenominal possessor (''Johns brother''). However, in some situations, it may also use a postnominal possessor, as in ''the brother of John''.

Therefore, the pronominal possessor patterns with pronominal binding in the alienable construction, but the pronominal possessor patterns with anaphoric binding in the inalienable construction. In anaphoric binding, an anaphor requires a coreferent antecedent that c-commands the anaphor and that is in the domain of the anaphor. For example (1b) to obey those conditions, the pronominal possessor must refer to ''Lucy'', not to another possessor that is not mentioned in the sentence. Thus, by having only one grammatical interpretation, (1b) is consistent with anaphoric binding. On the other hand, the interpretation of alienable constructions such as 1a can be ambiguous since it is not restricted by the same properties of anaphoric binding.

Therefore, the pronominal possessor patterns with pronominal binding in the alienable construction, but the pronominal possessor patterns with anaphoric binding in the inalienable construction. In anaphoric binding, an anaphor requires a coreferent antecedent that c-commands the anaphor and that is in the domain of the anaphor. For example (1b) to obey those conditions, the pronominal possessor must refer to ''Lucy'', not to another possessor that is not mentioned in the sentence. Thus, by having only one grammatical interpretation, (1b) is consistent with anaphoric binding. On the other hand, the interpretation of alienable constructions such as 1a can be ambiguous since it is not restricted by the same properties of anaphoric binding.

Alienability can be expressed only in attributive possession constructions, not in predicative possession.

Attributive possession is a type of possession in which the possessor and possessee form a

Alienability can be expressed only in attributive possession constructions, not in predicative possession.

Attributive possession is a type of possession in which the possessor and possessee form a

Inalienable possession can also be marked with external possession. Such constructions have the possessor appearing outside the determiner phrase. For example, the possessor may appear as a dative complement of the verb.

French exhibits both external possessor construction and internal possessor construction, as in (23):

However, those types of possessors are problematic. There is a discrepancy between the possessor appearing syntactically in an inalienable possession construction and what its semantic relationship to the inalienable noun seems to be. Semantically, the possessor of an inalienable noun is intrinsic to its meaning and acts like a semantic argument. On the surface syntactic structure, however, the possessor appears in a position that marks it as an argument of the verb. Thus, there are different views on how those types of inalienable possession constructions should be represented in the syntactic structure. The binding hypothesis argues that the possessor is an argument of the verb. Conversely, the possessor-raising hypothesis argues that the possessor originates as an argument of the possessed noun and then moves to a position in which on the surface, it looks like an argument of the verb.

Inalienable possession can also be marked with external possession. Such constructions have the possessor appearing outside the determiner phrase. For example, the possessor may appear as a dative complement of the verb.

French exhibits both external possessor construction and internal possessor construction, as in (23):

However, those types of possessors are problematic. There is a discrepancy between the possessor appearing syntactically in an inalienable possession construction and what its semantic relationship to the inalienable noun seems to be. Semantically, the possessor of an inalienable noun is intrinsic to its meaning and acts like a semantic argument. On the surface syntactic structure, however, the possessor appears in a position that marks it as an argument of the verb. Thus, there are different views on how those types of inalienable possession constructions should be represented in the syntactic structure. The binding hypothesis argues that the possessor is an argument of the verb. Conversely, the possessor-raising hypothesis argues that the possessor originates as an argument of the possessed noun and then moves to a position in which on the surface, it looks like an argument of the verb.

The French data below illustrate how the analysis is thought to work. The possessor ''lui'' originates in the specifier of DP as an argument of the noun ''figure''. That is equivalent to an underlying structure ''Gilles a lavé lui la figure''. The possessor raises to the specifier of VP, which is seen in the surface structure ''Gilles lui a lavé la figure''.

According to Guéron, a benefit of the hypothesis is that it is consistent with principles of syntactic movement such as locality of selection and

The French data below illustrate how the analysis is thought to work. The possessor ''lui'' originates in the specifier of DP as an argument of the noun ''figure''. That is equivalent to an underlying structure ''Gilles a lavé lui la figure''. The possessor raises to the specifier of VP, which is seen in the surface structure ''Gilles lui a lavé la figure''.

According to Guéron, a benefit of the hypothesis is that it is consistent with principles of syntactic movement such as locality of selection and  Norwegian treats kinship nouns and body-part nouns similarly in relation to bound variable interpretations. When a definite noun is present, it usually has a referential reading. In (29a), the referential reading is present. However, the presence of definite kinship or body part nouns may also bring about the bound variable reading in which a kinship or body part noun contains a variable bound by the quantifier in the subject, and (29b) may produce both the referential and bound variable readings. With the referential reading, the professors washed a face or father, mentioned earlier. With the bound variable reading, the professors washed their own face or father. Additionally, both kinship and body part nouns behave similarly in sentences with VP pronominalization. VP pronominalization involving both nouns allow for both a referential reading and a "sloppy reading", which involves variable binding. In (29c) in the referential reading, John and Mari wash a face or a mother been mentioned earlier. In the "sloppy reading", John washes his face or mother, and Mari washes hers.

Finally, both kinship and body part nouns bear similarities in locality. Both behave in such a way that the definite form of the noun is bound by the closest subject. In (30a), the possessor must be the subordinate clause subject, not the main clause subject. Likewise, in (30b), the father mentioned is preferably the father of the subordinate clause subject referent, not of the main clause subject referent.

Norwegian treats kinship nouns and body-part nouns similarly in relation to bound variable interpretations. When a definite noun is present, it usually has a referential reading. In (29a), the referential reading is present. However, the presence of definite kinship or body part nouns may also bring about the bound variable reading in which a kinship or body part noun contains a variable bound by the quantifier in the subject, and (29b) may produce both the referential and bound variable readings. With the referential reading, the professors washed a face or father, mentioned earlier. With the bound variable reading, the professors washed their own face or father. Additionally, both kinship and body part nouns behave similarly in sentences with VP pronominalization. VP pronominalization involving both nouns allow for both a referential reading and a "sloppy reading", which involves variable binding. In (29c) in the referential reading, John and Mari wash a face or a mother been mentioned earlier. In the "sloppy reading", John washes his face or mother, and Mari washes hers.

Finally, both kinship and body part nouns bear similarities in locality. Both behave in such a way that the definite form of the noun is bound by the closest subject. In (30a), the possessor must be the subordinate clause subject, not the main clause subject. Likewise, in (30b), the father mentioned is preferably the father of the subordinate clause subject referent, not of the main clause subject referent.

On the other hand, definite kinship and body-part nouns in Norwegian have a syntactic difference. Definite body part nouns allow a first- or second-person possessor, but some definite kinship nouns do not. For instance, the sentence in (31a) is not allowed as it contains a first-person possessor and kinship term. The kinship term can be used only with a third-person possessor, such as in (31b).

On the other hand, definite kinship and body-part nouns in Norwegian have a syntactic difference. Definite body part nouns allow a first- or second-person possessor, but some definite kinship nouns do not. For instance, the sentence in (31a) is not allowed as it contains a first-person possessor and kinship term. The kinship term can be used only with a third-person possessor, such as in (31b).

However, body part nouns do not have the restriction on first- or second-person possessors like in (32).

However, body part nouns do not have the restriction on first- or second-person possessors like in (32).