Hyde Park, London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hyde Park is a , historic Grade I-listed

The first coherent landscaping in Hyde Park began in 1726. It was undertaken by Charles Bridgeman for King George I; after the king's death in 1727, it continued with approval of his daughter-in-law, Queen Caroline. Work was supervised by Charles Withers, the Surveyor-General of Woods and Forests, and divided Hyde Park, creating Kensington Gardens. The Serpentine was formed by damming the

The first coherent landscaping in Hyde Park began in 1726. It was undertaken by Charles Bridgeman for King George I; after the king's death in 1727, it continued with approval of his daughter-in-law, Queen Caroline. Work was supervised by Charles Withers, the Surveyor-General of Woods and Forests, and divided Hyde Park, creating Kensington Gardens. The Serpentine was formed by damming the

Hyde Park hosted a Great Fair in the summer of 1814 to celebrate the Allied sovereigns' visit to England, and exhibited various stalls and shows. The

Hyde Park hosted a Great Fair in the summer of 1814 to celebrate the Allied sovereigns' visit to England, and exhibited various stalls and shows. The  On 20 July 1982, a

On 20 July 1982, a

An early description reports:

An early description reports:

Popular areas within Hyde Park include Speakers' Corner (located in the northeast corner near Marble Arch), close to the former site of the Tyburn gallows, and Rotten Row, which is the northern boundary of the site of the Crystal Palace.

Popular areas within Hyde Park include Speakers' Corner (located in the northeast corner near Marble Arch), close to the former site of the Tyburn gallows, and Rotten Row, which is the northern boundary of the site of the Crystal Palace.

The music management company Blackhill Enterprises held the first rock concert in Hyde Park on 29 June 1968, attended by 15,000 people. On the bill were

The music management company Blackhill Enterprises held the first rock concert in Hyde Park on 29 June 1968, attended by 15,000 people. On the bill were

There are five

There are five

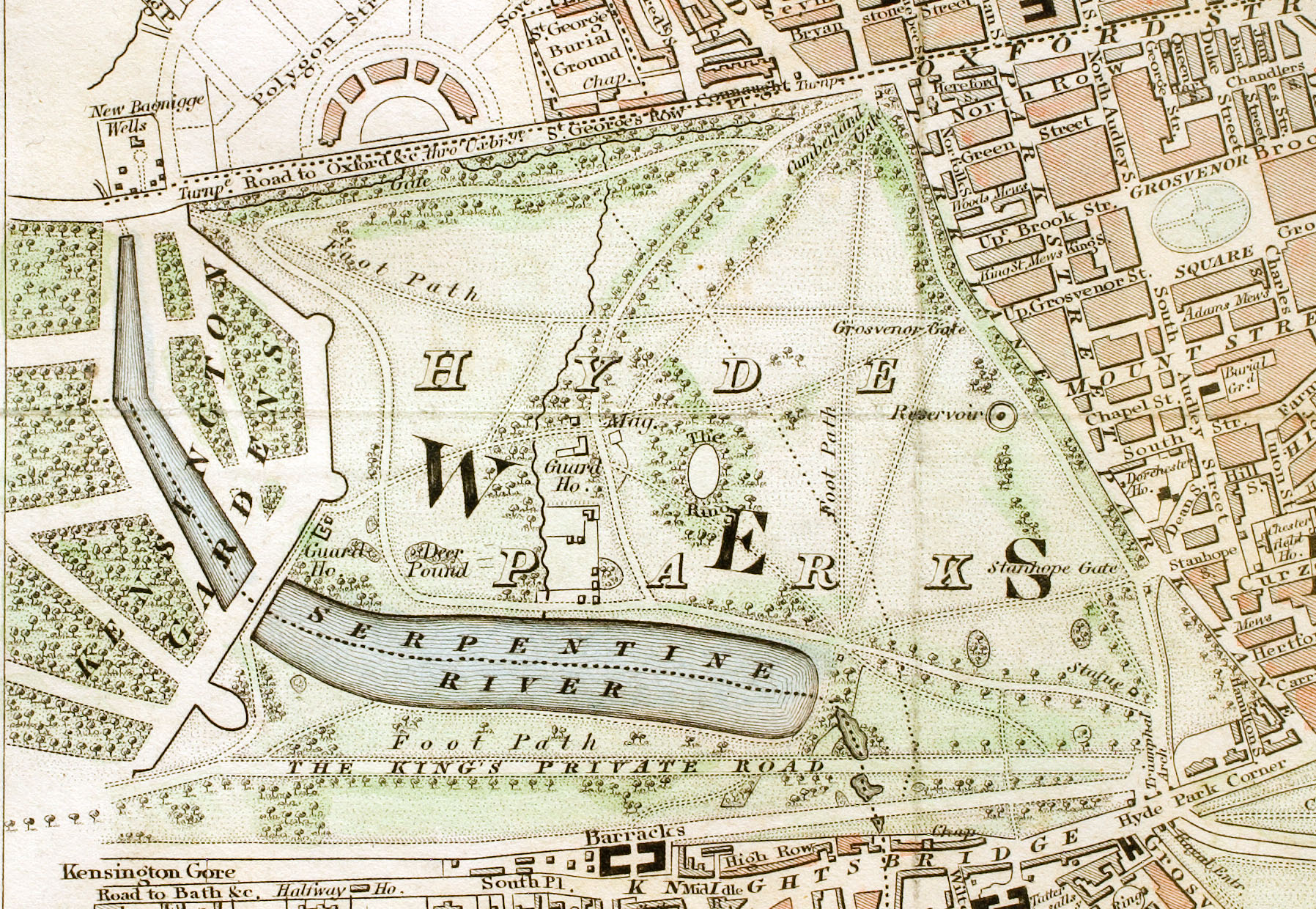

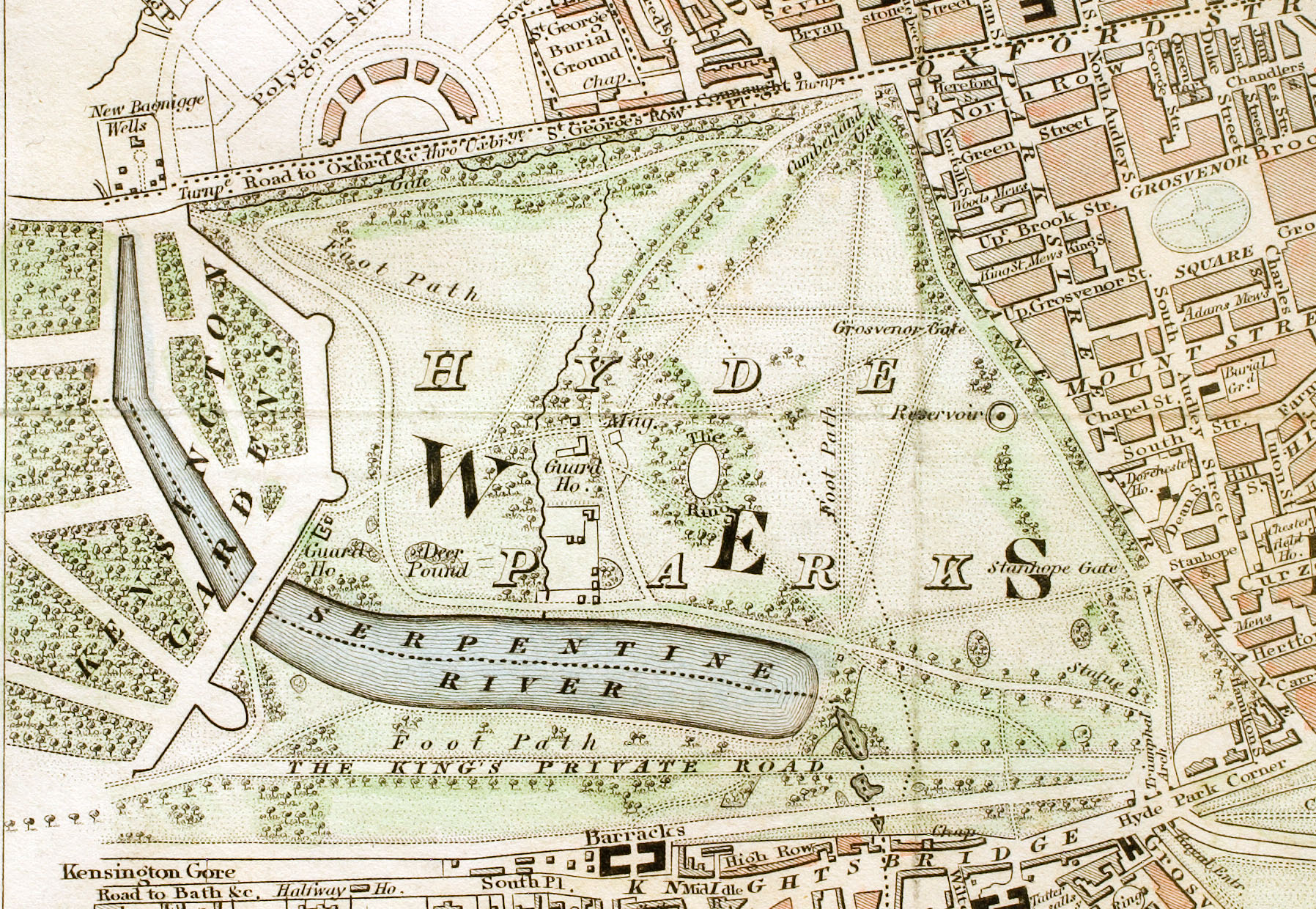

Map showing Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens

{{Authority control Venues of the 2012 Summer Olympics Urban public parks Olympic swimming venues Olympic triathlon venues Parks and open spaces in the City of Westminster Royal Parks of London Great Exhibition World's fair sites in England Decimus Burton buildings Grade I listed parks and gardens in London Urban public parks in the United Kingdom

urban park

An urban park or metropolitan park, also known as a city park, municipal park (North America), public park, public open space, or municipal gardens (United Kingdom, UK), is a park or botanical garden in cities, densely populated suburbia and oth ...

in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, Greater London. A Royal Park, it is the largest of the parks and green spaces that form a chain from Kensington Palace through Kensington Gardens

Kensington Gardens, once the private gardens of Kensington Palace, are among the Royal Parks of London. The gardens are shared by the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and sit immediately to the west of Hyde Pa ...

and Hyde Park, via Hyde Park Corner and Green Park

The Green Park, one of the Royal Parks of London, is in the City of Westminster, Central London. Green Park is to the north of the gardens and semi-circular forecourt of Buckingham Palace, across Constitution Hill road. The park is in the m ...

, past Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

to St James's Park. Hyde Park is divided by the Serpentine and the Long Water lakes.

The park was established by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

in 1536 when he took the land from Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

and used it as a hunting ground. It opened to the public in 1637 and quickly became popular, particularly for May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

parades. Major improvements occurred in the early 18th century under the direction of Queen Caroline. The park also became a place for duels during this time, often involving members of the nobility. In the 19th century, the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851 was held in the park, for which The Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton

Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was an English gardener, architect, engineer and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Member of Parliament. He is best known for designing the Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde ...

, was erected.

Free speech and demonstrations have been a key feature of Hyde Park since the 19th century. Speakers' Corner has been established as a point of free speech and debate since 1872, while the Chartists, the Reform League, the suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for women's suffrage, the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in part ...

, and the Stop the War Coalition

The Stop the War Coalition (StWC), informally known simply as Stop the War, is a British group that campaigns against the United Kingdom's involvement in military conflicts.

It was established on 21 September 2001 to campaign against the impe ...

have all held protests there. In the late 20th century, the park was known for holding large-scale free rock music concerts, featuring groups such as Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1965. Gaining an early following as one of the first British psychedelic music, psychedelic groups, they were distinguished by their extended compositions, sonic experiments ...

, the Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for over six decades, they are one of the most popular, influential, and enduring bands of the Album era, rock era. In the early 1960s, the band pione ...

and Queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

. Major events in the park have continued into the 21st century, such as Live 8

Live 8 was a string of benefit concerts that took place on 2 July 2005, in the G8 states and South Africa. They were timed to precede the G8 conference and summit held at the Gleneagles Hotel in Auchterarder, Scotland, from 6–8 July 2005 ...

in 2005, and the annual Hyde Park Winter Wonderland from 2007.

Geography

Hyde Park is a Royal Park in central London, bounded on the north by Bayswater Road, to the east by Park Lane, and to the south byKnightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

. Further north is Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

, further east is Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

and further south is Belgravia. To the southeast, outside the park, is Hyde Park Corner, beyond which is Green Park

The Green Park, one of the Royal Parks of London, is in the City of Westminster, Central London. Green Park is to the north of the gardens and semi-circular forecourt of Buckingham Palace, across Constitution Hill road. The park is in the m ...

, St. James's Park and Buckingham Palace Gardens. The park has been Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens since 1987.

To the west, Hyde Park merges with Kensington Gardens

Kensington Gardens, once the private gardens of Kensington Palace, are among the Royal Parks of London. The gardens are shared by the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and sit immediately to the west of Hyde Pa ...

. The dividing line runs approximately between Alexandra Gate to Victoria Gate via West Carriage Drive and the Serpentine Bridge. The Serpentine is to the south of the park area. Kensington Gardens has been separate from Hyde Park since 1728, when Queen Caroline divided them. Hyde Park covers , and Kensington Gardens covers , giving a total area of . During daylight, the two parks merge seamlessly into each other, but Kensington Gardens closes at dusk, and Hyde Park remains open throughout the year from 5 a.m. until midnight.

History

Early history

The park's name comes from the Manor of Hyde, which was the northeast sub-division of the manor of Eia (the other two sub-divisions were Ebury and Neyte) and appears as such in theDomesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

. The name is believed to be of Saxon origin, and means a unit of land, the hide, that was appropriate for the support of a single family and dependents. Through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, it was property of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, and the woods in the manor were used both for firewood and shelter for game

A game is a structured type of play usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or video games) or art ...

.

16th–17th centuries

Hyde Park was created for hunting by Henry Vlll in 1536 after he acquired the manor of Hyde from the Abbey. It was enclosed as a deer park and remained a private hunting ground until James I permitted limited access to gentlefolk, appointing a ranger to take charge. In October 1619, keepers directed by Sir Thomas Watson ambushed deer poachers with hail shot, and the poachers killed a keeper. Charles I created the Ring (north of the present Serpentine boathouses), and in 1637 he opened the park to the general public. It quickly became a popular gathering place, particularly for May Day celebrations. At the start of theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

in 1642, a series of fortifications were built along the east side of the park, including forts at what is now Marble Arch, Mount Street and Hyde Park Corner. The latter included a strongpoint where visitors to London could be checked and vetted.

In 1652, during the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

, Parliament ordered the then park to be sold for "ready money". It realised £17,000 with an additional £765 6s 2d for the resident deer. Following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Charles II resumed ownership of Hyde Park and enclosed it with a brick wall. He restocked deer in what is now Buck Hill in Kensington Gardens. The May Day parade continued to be a popular event; Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

took part in the park's celebrations in 1663 while attempting to gain the King's favour.

During the Great Plague of London in 1665, Hyde Park was used as a military camp.

18th century

In 1689, William III moved his residence to Kensington Palace on the far side of Hyde Park and had a drive laid out across its southern edge which was known as the King's Private Road. The drive is still in existence as a wide straight gravelled carriage track leading west from Hyde Park Corner across the southern boundary of Hyde Park towards Kensington Palace and now known as Rotten Row, possibly a corruption of ''rotteran'' (to muster), ''Ratten Row'' (roundabout way), ''Route du roi'', or ''rotten'' (the soft material with which the road is covered). It is believed to be the first road in London to be lit at night, which was done to deter highwaymen. In 1749,Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (; 24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English Whig politician, writer, historian and antiquarian.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twickenham, southwest London ...

was robbed while travelling through the park from Holland House. The row was used by the wealthy for riding in the early 19th century.

Hyde Park was a popular duelling spot during the 18th century, with 172 taking place, causing 63 deaths. The Hamilton–Mohun duel took place there in 1712, when Charles Mohun, 4th Baron Mohun, fought James Hamilton, 4th Duke of Hamilton. Baron Mohun was killed instantly, and the Duke died shortly afterwards. John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

fought Samuel Martin in 1772, the year in which Richard Brinsley Sheridan duelled with Captain Thomas Mathews over the latter's libellous comments about Sheridan's fiancée, Elizabeth Ann Linley. Edward Thurlow, 1st Baron Thurlow, fought Andrew Stuart in a Hyde Park duel in 1770. Military executions were common in Hyde Park at this time; John Rocque's Map of London, 1746, marks a point inside the park, close to the Tyburn gallows, as "where soldiers are shot."

The first coherent landscaping in Hyde Park began in 1726. It was undertaken by Charles Bridgeman for King George I; after the king's death in 1727, it continued with approval of his daughter-in-law, Queen Caroline. Work was supervised by Charles Withers, the Surveyor-General of Woods and Forests, and divided Hyde Park, creating Kensington Gardens. The Serpentine was formed by damming the

The first coherent landscaping in Hyde Park began in 1726. It was undertaken by Charles Bridgeman for King George I; after the king's death in 1727, it continued with approval of his daughter-in-law, Queen Caroline. Work was supervised by Charles Withers, the Surveyor-General of Woods and Forests, and divided Hyde Park, creating Kensington Gardens. The Serpentine was formed by damming the River Westbourne

The Westbourne or Kilburn, also known as the Ranelagh Sewer, is a culverted small Tributaries of the River Thames#Tributaries, River Thames tributary in London, rising in Hampstead and Brondesbury Park and which as a drain unites and flows so ...

, which runs through the park from Kilburn towards the Thames. It is divided from the Long Water by a bridge designed by George Rennie in 1826.

The work was completed in 1733. The 2nd Viscount Weymouth was made Ranger of Hyde Park in 1739 and shortly after began digging the Serpentine lakes at Longleat. A powder magazine was built north of the Serpentine in 1805.

19th–21st centuries

Hyde Park hosted a Great Fair in the summer of 1814 to celebrate the Allied sovereigns' visit to England, and exhibited various stalls and shows. The

Hyde Park hosted a Great Fair in the summer of 1814 to celebrate the Allied sovereigns' visit to England, and exhibited various stalls and shows. The Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

was re-enacted on the Serpentine, with a band playing the National Anthem while the French fleet sank into the lake. The coronation of King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

in 1821 was celebrated with a fair in the park, including an air balloon and firework displays.

One of the most important events to take place in Hyde Park was the Great Exhibition of 1851

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

. The Crystal Palace was constructed on the south side of the park. The public did not want the building to remain after the closure of the exhibition, and its architect, Joseph Paxton

Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was an English gardener, architect, engineer and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Member of Parliament. He is best known for designing the Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde ...

, raised funds and purchased it. He had it moved to Sydenham Hill in South London. Another significant event was the first Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

investiture, on 26 June 1857, when 62 men were decorated by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

in the presence of Prince Albert and other members of the Royal Family, including their future son-in-law Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia.

The Hyde Park Lido sits on the south bank of the Serpentine. It opened in 1930 to provide improved support for bathing and sunbathing in the park, which had been requested by the naturist group, the Sunlight League. The Lido and accompanying Pavilion was designed by the Commissioner of Works, George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1 ...

, and was half funded by a £5,000 (now equivalent to £) donation from Major Colin Cooper (1892–1938). It still sees regular use in the summer.

Hyde Park has been a major venue for several Royal jubilees and celebrations. For the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887, a party was organised on 22 June where around 26,000 school children were given a free meal as a gift. The Queen and the Prince of Wales made an unexpected appearance at the event. Victoria remained fond of Hyde Park in the final years of her life and often drove there twice a day.

As part of the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 1977, a Jubilee Exhibition was set up in Hyde Park, with the Queen and Prince Philip visiting on 30 June. In 2012, a major festival took place in the park as part of the Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations. On 6 February, the King's Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, fired a 41-gun Royal Salute at Hyde Park Corner.

On 20 July 1982, a

On 20 July 1982, a Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

killed four soldiers and seven horses. A memorial was constructed to the left of the Albert Gate to commemorate the soldiers and horses killed in the blast.

Since 2007, Hyde Park has played host to the annual Winter Wonderland

"Winter Wonderland" is a song written in 1934 by Felix Bernard and lyricist Richard Bernhard Smith. Due to its seasonal theme, it is often regarded as a Christmas song in the Northern Hemisphere. Since its original recording by Richard Himb ...

event, which features numerous Christmas-themed markets, along with various rides and attractions, alongside bars and restaurants. It has become one of the largest Christmas events in Europe, having attracted over 14 million visitors as of 2016, and has expanded to include the largest ice rink in London, live entertainment and circuses.

On 18 September 2010, Hyde Park was the setting for a prayer vigil with Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

as part of his visit to the United Kingdom, attended by around 80,000 people. A large crowd assembled along the Mall to see the Pope arrive for his address. An attempt to assassinate the Pope had been foiled after five people dressed as street cleaners were spotted within a mile of Hyde Park, and arrested along with a sixth suspect. They were later released without charge as police said they posed no credible threat.

Grand Entrance

During the late 18th century, plans were made to replace the old toll gate at Hyde Park Corner with a grander entrance, following the gentrification of the area surrounding it. The first design was put forward byRobert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (architect), William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and train ...

in 1778 as a grand archway, followed by John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor ...

's 1796 proposal to build a new palace adjacent to the corner in Green Park.

Following the construction of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

, the improvement plans were revisited. The grand entrance to the park at Hyde Park Corner was designed by Decimus Burton, and was constructed in the 1820s. Burton laid out the paths and driveways and designed a series of lodges, the Screen/Gate at Hyde Park Corner (also known as the Grand Entrance or the Apsley Gate) in 1825 and the Wellington Arch, which opened in 1828. The Screen and the Arch originally formed a single composition, designed to provide a monumental transition between Hyde Park and Green Park, although the arch was moved in 1883. It originally had a statue of the Duke of Wellington on top; it was moved to Aldershot

Aldershot ( ) is a town in the Rushmoor district, Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme north-east corner of the county, south-west of London. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Farnborough/Aldershot built-up are ...

in 1883 when the arch was re-sited.

An early description reports:

An early description reports:

"It consists of a screen of handsome fluted Ionic columns, with three carriage entrance archways, two-foot entrances, a lodge, etc. The extent of the whole frontage is about . The central entrance has a bold projection: the entablature is supported by four columns; and the volutes of the capitals of the outside column on each side of the gateway are formed in an angular direction, so as to exhibit two complete faces to view. The two side gateways, in their elevations, present two insulated Ionic columns, flanked by antae. All these entrances are finished by a blocking, the sides of the central one being decorated with a beautiful frieze, representing a naval and military triumphal procession. This frieze was designed by Mr. Henning, junior, the son of Mr. Henning who was well known for his models of theThe Wellington Arch was extensively restored byElgin Marbles The Elgin Marbles ( ) are a collection of Ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon and other structures from the Acropolis of Athens, removed from Ottoman Greece in the early 19th century and shipped to Britain by agents of Thomas Bruce, 7 .... The gates were manufactured by Messrs. Bramah. They are of iron, bronzed, and fixed or hung to the piers by rings of gun-metal. The design consists of a beautiful arrangement of the Greek honeysuckle ornament; the parts being well defined, and the raffles of the leaves brought out in a most extraordinary manner."

English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, a battlefield, medieval castles, Roman forts, historic industrial sites, Lis ...

between 1999 and 2001. It is now open to the public, who can see a view of the parks from its platforms above the porticoes.

Features

Popular areas within Hyde Park include Speakers' Corner (located in the northeast corner near Marble Arch), close to the former site of the Tyburn gallows, and Rotten Row, which is the northern boundary of the site of the Crystal Palace.

Popular areas within Hyde Park include Speakers' Corner (located in the northeast corner near Marble Arch), close to the former site of the Tyburn gallows, and Rotten Row, which is the northern boundary of the site of the Crystal Palace.

Botany

Flowers were first planted in Hyde Park in 1860 by William Andrews Nesfield. The next year, the Italian Water Garden was constructed at Victoria Gate, including fountains and a summer house. Queen Anne's Alcove was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and was moved to the park from its original location in Kensington Gardens. During the late 20th century, over 9,000 elm trees in Hyde Park were killed by Dutch elm disease. This included many trees along the great avenues planted by Queen Caroline, which were ultimately replaced by limes and maples. The park now holds ofgreenhouse

A greenhouse is a structure that is designed to regulate the temperature and humidity of the environment inside. There are different types of greenhouses, but they all have large areas covered with transparent materials that let sunlight pass an ...

s which hold the bedding plants for the Royal Parks. A scheme is available to adopt trees in the park, which helps fund their upkeep and maintenance. A botanical curiosity is the weeping beech, which is known as "the upside-down tree". A rose garden, designed by Colvin & Moggridge Landscape Architects, was added in 1994.

Monuments

There are a number of assorted statues and memorials around Hyde Park. The Cavalry Memorial was built in 1924 at Stanhope Gate. It moved to the Serpentine Road when Park Lane was widened to traffic in 1961. South of the Serpentine is the Diana, Princess of Wales memorial, an oval stone ring fountain opened on 6 July 2004. To the east of the Serpentine, just beyond the dam, is Britain's Holocaust Memorial. The 7 July Memorial in the park commemorates the victims of7 July 2005 London bombings

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, also referred to as 7/7, were a series of four co-ordinated suicide attacks carried out by Islamist terrorists that targeted commuters travelling on Transport in London, London's public transport during the ...

.

The Standing Stone is a monolith at the centre of the Dell, in the east of Hyde Park. Made of Cornish stone, it was originally part of a drinking fountain, though an urban legend

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

was established, claiming it was brought from Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric Megalith, megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, to ...

by Charles I.

An assortment of unusual sculptures are scattered around the park, including: '' Still Water'', a massive horse head lapping up water; ''Jelly Baby Family'', a family of giant Jelly Babies standing on top of a large black cube; and ''Vroom Vroom'', which resembles a giant human hand pushing a toy car along the ground. The sculptor Jacob Epstein constructed several works in Hyde Park. His memorial to the author William Henry Hudson, featuring his character ''Rima'' caused public outrage when it was unveiled in 1925.

There has been a fountain at Grosvenor Gate since 1863, designed by Alexander Munro. There is another fountain opposite Mount Street on the park's eastern edge.

A pet cemetery

A pet cemetery is a cemetery for pets. Although the veneration and burial of beloved pets has been practiced since ancient times, burial grounds reserved specifically for animals were not common until the late 19th century.

History

Many hum ...

was established at the north edge of Hyde Park in the late 19th century. The last burial took place in 1976.

Police station

Currently, the Metropolitan Police Service is responsible for policing the park and are based inside what is colloquially known as 'the Old Police House', which is situated within the park. The building was designed by John Dixon Butler, who was the forces's surveyor between 1895 and 1920. For the police, he completed around 200 buildings, including the Former New Scotland Yard, Norman Shaw South Building (assisting Richard Norman Shaw); the adjoining Canon Row Police Station; Bow Road Police Station, Tower Hamlets; Tower Bridge Magistrates Court and adjoining Police Station; and 19–21 Great Marlborough Street, Westminster (court and police station). The architectural historian describes the building as being like, from a distance, "a medium-sized country house of Charles II’s time." Hyde Park was policed by the Metropolitan Police from 1867 until 1993, when policing of the park was handed over to the Royal Parks Constabulary. In 2004 this changed back to the Metropolitan Police, following a review of the Royal Parks Constabulary by Anthony Speed.Debates

Hyde Park's Speakers' Corner has acquired an international reputation for demonstrations and other protests due to its tolerance of free speech. In 1855, a protest at the park was organised to demonstrate against Robert Grosvenor's attempt to ban Sunday trading, including a restriction on pub opening times.Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

observed that approximately 200,000 protesters attended the demonstration, which involved jeering and taunting at upper-class horse carriages. A further protest occurred a week later, but this time the police attacked the crowd.

In 1867 the policing of the park was entrusted to the Metropolitan Police, the only royal park so managed, due to the potential for trouble at Speakers' Corner. A Metropolitan Police station ('AH') is situated in the middle of the park. Covering Hyde Park and sixteen other royal parks (mostly in London), the 1872 Parks Regulation Act formalised the position of "park keeper" and also provided that "Every police constable belonging to the police force of the district in which any park, garden, or possession to which this Act applies is situate shall have the powers, privileges, and immunities of a park-keeper within such park, garden, or possession."

Speakers' Corner became increasingly popular in the late 19th century. Visitors brought along placards, stepladders and soap boxes in order to stand out from others, while heckling of speakers was popular. The rise of the Internet, particularly blogs, has diminished the importance of Speakers' Corner as a political platform, and it is increasingly seen as simply a tourist attraction.

As well as Speakers' Corner, several important mass demonstrations have occurred in Hyde Park. On 26 July 1886, the Reform League staged a march from their headquarters towards the park, campaigning for increased suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and representation. Though the police had closed the park, the crowd managed to break down the perimeter railings and get inside, leading to the event being dubbed "The Hyde Park Railings Affair". After the protests turned violent, three squadrons of Horse Guards and numerous Foot Guards were sent out from Marble Arch to combat the situation. On 21 June 1908, as part of " Women's Sunday", a reported 750,000 people marched from the Embankment to Hyde Park protesting for votes for women

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. The first protest against the planned 2003 invasion of Iraq took place in Hyde Park on 28 September 2002, with 150,000–350,000 in attendance. A further series of demonstrations happened around the world, culminating in the 15 February 2003 anti-war protests, part of a global demonstration against the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

. Over a million protesters are reported to have attended the Hyde Park event alone.

Concerts

The bandstand in Hyde Park was built in Kensington Gardens in 1869 and moved to its present location in 1886. It became a popular place for concerts in the 1890s, featuring up to three every week. Military and brass bands continued to play there into the 20th century. The music management company Blackhill Enterprises held the first rock concert in Hyde Park on 29 June 1968, attended by 15,000 people. On the bill were

The music management company Blackhill Enterprises held the first rock concert in Hyde Park on 29 June 1968, attended by 15,000 people. On the bill were Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1965. Gaining an early following as one of the first British psychedelic music, psychedelic groups, they were distinguished by their extended compositions, sonic experiments ...

, Roy Harper and Jethro Tull, while John Peel later said it was "the nicest concert I’ve ever been to". Subsequently, Hyde Park has featured some of the most significant concerts in rock. The supergroup Blind Faith

Blind Faith were an English rock supergroup that consisted of Steve Winwood, Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, and Ric Grech. They followed the success of each of the member's former bands, including Clapton and Baker's former group Cream and ...

(featuring Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English Rock music, rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s l ...

and Steve Winwood) played their debut gig in Hyde Park on 7 June 1969. The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for over six decades, they are one of the most popular, influential, and enduring bands of the Album era, rock era. In the early 1960s, the band pione ...

headlined a concert (later released as The Stones in the Park) on 5 July that year, two days after the death of founding member Brian Jones

Lewis Brian Hopkin Jones (28 February 1942 – 3 July 1969) was an English musician and founder of the Rolling Stones. Initially a slide guitarist, he went on to sing backing vocals and played a wide variety of instruments on Rolling Stones r ...

, and is now remembered as one of the most famous gigs of the 1960s. Pink Floyd returned to Hyde Park on 18 July 1970, playing new material from '' Atom Heart Mother''. All of the early gigs from 1968 to 1971 were free events, contrasting sharply with the later commercial endeavours.

Queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

played a free concert organised by Richard Branson

Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson (born 18 July 1950) is an English business magnate who co-founded the Virgin Group in 1970, and controlled 5 companies remaining of once more than 400.

Branson expressed his desire to become an entrepreneu ...

in the park on 18 September 1976, partway through recording the album '' A Day at the Races''. The band drew an audience of 150,000 – 200,000, which remains the largest crowd for a Hyde Park concert. The group were not allowed to play an encore, and police threatened to arrest frontman Freddie Mercury

Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara; 5 September 1946 – 24 November 1991) was a British singer and songwriter who achieved global fame as the lead vocalist and pianist of the rock band Queen (band), Queen. Regarded as one of the gre ...

if he attempted to do so.

The British Live 8

Live 8 was a string of benefit concerts that took place on 2 July 2005, in the G8 states and South Africa. They were timed to precede the G8 conference and summit held at the Gleneagles Hotel in Auchterarder, Scotland, from 6–8 July 2005 ...

concert took place in Hyde Park on 2 July 2005, as a concert organised by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to raise awareness of increased debts and poverty in the third world

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

. Acts included U2, Coldplay

Coldplay are a British Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1997. They consist of vocalist and pianist Chris Martin, guitarist Jonny Buckland, bassist Guy Berryman, drummer and percussionist Will Champion, and manager Phil Harvey (band m ...

, Elton John

Sir Elton Hercules John (born Reginald Kenneth Dwight; 25 March 1947) is a British singer, songwriter and pianist. His music and showmanship have had a significant, lasting impact on the music industry, and his songwriting partnership with l ...

, R.E.M., Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone ( ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer, songwriter, record producer, and actress. Referred to as the "Queen of Pop", she has been recognized for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, ...

, The Who

The Who are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1964. Their classic lineup (1964–1978) consisted of lead vocalist Roger Daltrey, guitarist Pete Townshend, bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon. Considered one of th ...

, and Paul McCartney

Sir James Paul McCartney (born 18 June 1942) is an English singer, songwriter and musician who gained global fame with the Beatles, for whom he played bass guitar and the piano, and shared primary songwriting and lead vocal duties with John ...

, and the most anticipated set was the reformation of the classic 1970s line-up of Pink Floyd (including David Gilmour and Roger Waters

George Roger Waters (born 6 September 1943) is an English musician and singer-songwriter. In 1965, he co-founded the rock band Pink Floyd as the bassist. Following the departure of the group's main songwriter Syd Barrett in 1968, Waters became ...

) for the first time since 1981. The gig was the Floyd's final live performance.

Acts from each of the four nations in the UK played a gig in the park as part of the opening ceremony for the 2012 Summer Olympics

The 2012 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the XXX Olympiad and also known as London 2012, were an international multi-sport event held from 27 July to 12 August 2012 in London, England, United Kingdom. The first event, the ...

. The headliners were Duran Duran

Duran Duran () are an English pop rock band formed in Birmingham in 1978 by singer Stephen Duffy, keyboardist Nick Rhodes and guitarist/bassist John Taylor (bass guitarist), John Taylor. After several early changes, the band's line-up settled ...

, representing England, alongside the Stereophonics

Stereophonics are a Welsh pop and rock music, Welsh rock band formed in 1992 in the village of Cwmaman in the Cynon Valley. The band consists of Kelly Jones (lead vocals, lead guitar, keyboards), Richard Jones (Stereophonics), Richard Jones (n ...

for Wales, Paolo Nutini for Scotland, and Snow Patrol for Northern Ireland. Since 2011, Radio 2 Live in Hyde Park has taken place each September.

Hyde Park host the annual music festival BST Hyde Park, headlined by artists including Adele, Arcade Fire

Arcade Fire is a Canadian indie rock band from Montreal, Quebec, consisting of husband and wife Win Butler and Régine Chassagne, alongside Richard Reed Parry, Tim Kingsbury, and Jeremy Gara. The band's touring line-up includes former core ...

, Sabrina Carpenter, Guns N' Roses

Guns N' Roses is an American hard rock band formed in Los Angeles, California in 1985 as a merger of local bands L.A. Guns and Hollywood Rose. When they signed to Geffen Records in 1986, the band's "classic" line-up consisted of vocalist Axl R ...

, Lana Del Rey, Taylor Swift

Taylor Alison Swift (born December 13, 1989) is an American singer-songwriter. Known for her autobiographical songwriting, artistic versatility, and Cultural impact of Taylor Swift, cultural impact, Swift is one of the Best selling artists, w ...

& Olivia Rodrigo

Local residents have become critical of Hyde Park as a concert venue, due to the sound levels, and have campaigned for a maximum sound level of 73 decibels

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whose levels differ by one decibel have a ...

. In July 2012, Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen (born September 23, 1949) is an American Rock music, rock singer, songwriter, and guitarist. Nicknamed "the Boss", Springsteen has released 21 studio albums spanning six decades; most of his albums feature th ...

and Paul McCartney

Sir James Paul McCartney (born 18 June 1942) is an English singer, songwriter and musician who gained global fame with the Beatles, for whom he played bass guitar and the piano, and shared primary songwriting and lead vocal duties with John ...

found their microphones switched off after Springsteen had played a three-hour set during the Park's Hard Rock Calling festival, and overshot the 10:30 pm curfew time.

Sports

Hyde Park contains several sporting facilities, including severalfootball pitch

A football pitch or soccer field is the playing surface for the game of association football. Its dimensions and markings are defined by Law 1 of the Laws of the Game (association football), Laws of the Game, "The Field of Play". The pitch is ty ...

es and a Tennis

Tennis is a List of racket sports, racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles (tennis), singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles (tennis), doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket st ...

centre. There are numerous cycle paths, and horse riding is popular.

In 1998 British artist Marion Coutts recreated Hyde Park, along with Battersea and Regent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden (and historical ...

, as a set of asymmetrical ping-pong

Table tennis (also known as ping-pong) is a racket sport derived from tennis but distinguished by its playing surface being atop a stationary table, rather than the Tennis court, court on which players stand. Either individually or in teams of ...

tables for her interactive installation ''Fresh Air''.

For the 2012 Summer Olympics

The 2012 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the XXX Olympiad and also known as London 2012, were an international multi-sport event held from 27 July to 12 August 2012 in London, England, United Kingdom. The first event, the ...

, the park hosted the triathlon

A triathlon is an endurance multisport race consisting of Swimming (sport), swimming, Cycle sport, cycling, and running over various distances. Triathletes compete for fastest overall completion time, racing each segment sequentially with the ...

, which brothers Alistair Brownlee and Jonathan Brownlee took the Gold and Bronze medals for Team GB, and the 10 km open water swimming

Open water swimming is a swimming discipline which takes place in outdoor bodies of water such as open oceans, lakes, and rivers. Competitive open water swimming is governed by the International Swimming Federation, World Aquatics (formerly kno ...

events. The park has also hosted the ITU World Triathlon Grand Final.

Transport

London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

stations located on or near the edges of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens

Kensington Gardens, once the private gardens of Kensington Palace, are among the Royal Parks of London. The gardens are shared by the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and sit immediately to the west of Hyde Pa ...

(which is contiguous with Hyde Park). In clockwise order starting from the south-east, they are:

* Hyde Park Corner ( Piccadilly line)

*Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

(Piccadilly line)

* Queensway ( Central line)

* Lancaster Gate (Central line)

* Marble Arch (Central line)

Bayswater tube station, on the Circle and District

A district is a type of administrative division that in some countries is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municip ...

lines, is also close to Queensway station and the north-west corner of the park. High Street Kensington tube station, on the Circle and District

A district is a type of administrative division that in some countries is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municip ...

is very close to Kensington Palace located on the Southwest corner of Kensington Gardens. Paddington station, served by Bakerloo, Circle and District, and Hammersmith & City lines, is close to Lancaster Gate station and a short walk away from Hyde Park.

Several main roads run around the perimeter of Hyde Park. Park Lane is part of the London Inner Ring Road and the London Congestion Charge zone boundary. Transport within the park for people lacking mobility and disabled visitors is provided free of charge by Liberty Drives, located at Triangle Carpark.

Cycle Superhighway 3 (CS3) begins at Lancaster Gate, on the northern perimeter of Hyde Park. It is one of several TfL-coordinated cycle routes to cross the Park. CS3 also crosses Hyde Park Corner on its route towards Westminster and the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

. The route opened in September 2018 and is signposted and cyclists are segregated from other road traffic on wide cycle tracks.See also

* Hyde Park, Boston * Hyde Park, ChicagoNotes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *External links

*Map showing Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens

{{Authority control Venues of the 2012 Summer Olympics Urban public parks Olympic swimming venues Olympic triathlon venues Parks and open spaces in the City of Westminster Royal Parks of London Great Exhibition World's fair sites in England Decimus Burton buildings Grade I listed parks and gardens in London Urban public parks in the United Kingdom