Hubert Wilkins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir George Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar (31 October 188830 November 1958), commonly referred to as Captain Wilkins, was an Australian polar explorer,

After the war, Wilkins served in 1921–22 as an

After the war, Wilkins served in 1921–22 as an

. American Geographical Society. Retrieved 17 June 2010. He was also awarded the

Jean Jules Verne et Lady Wilkins 1931.jpg

Ellsworth contributed $70,000, plus a $20,000 loan. Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst purchased exclusive rights to the story for $61,000. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute contributed a further $35,000. Wilkins himself added $25,000 of his own money. Since Wilkins was not a U.S. citizen, he was unable to purchase the 1918 submarine scheduled to be decommissioned, but he was permitted to lease the vessel for a period of five years at a cost of one dollar annually from Lake & Danenhower, Inc. The submarine was the disarmed ''O-12'', and was commanded by Sloan Danenhower (former commanding officer of ''C-4''.) Wilkins renamed her ''Nautilus'', after Jules Verne's ''20,000 Leagues Under the Sea''. The submarine was outfitted with a custom-designed drill that would allow her to bore through ice pack overhead for ventilation. The crew of eighteen men was chosen with great care. Among their ranks were U.S. Naval Academy graduates as well as navy veterans of WWI.''

Wilkins described the planned expedition in his 1931 book ''Under The North Pole'', which '' Wonder Stories'' praised as " sexciting as it is epochal".

Australian War Memorial

Entry for Sir George Hubert Wilkins

biography from Flinders Ranges Research

Short bio on Sir Hubert Wilkins

Searching for Sir Hubert

Documentary Filmmaker site

''Life&Times'' radio documentary, first broadcast by ABC Radio National, 29 August 2009 *

The Papers of George Hubert Wilkins

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkins, George Hubert 1888 births 1958 deaths Australian aviators Australian polar explorers Australian military personnel of World War I Australian ornithologists Australian photographers Australian Knights Bachelor Ohio State University faculty People from Hallett, South Australia Explorers of the Arctic Australian recipients of the Military Cross 20th-century Australian zoologists Members of the American Philosophical Society

ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

, pilot, soldier, geographer and photographer. He was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

after he assumed command of a group of American soldiers who had lost their officers during the Battle of the Hindenburg Line, and became the only official Australian photographer from any war to receive a combat medal.

He narrowly failed in an attempt to be the first to cross under the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

in a submarine, but was able to prove that submarines were capable of operating beneath the polar ice cap, thereby paving the way for future successful missions. The US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

later took his ashes to the North Pole aboard the submarine USS ''Skate'' on 17 March 1959.

Early life

Hubert Wilkins was a native of Mount Bryan East, South Australia, the last of 13 children in a family of pioneer settlers and sheep farmers. He was born at Mount Bryan East, South Australia, north of Adelaide by road. The original homestead has been restored by generous donation. He was educated at Mount Bryan East and the Adelaide School of Mines. As a teenager, he moved toAdelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

where he found work with a traveling cinema, to Sydney as a cinematographer, and thence to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

where he became a pioneering aerial photographer whilst working for Gaumont Studios. His photographic skill earned him a place on various Arctic expeditions, including the controversial 1913 Vilhjalmur Stefansson-led Canadian Arctic Expedition.

World War I

In 1917, Wilkins returned to his native Australia, joining the Australian Flying Corps in the rank of second lieutenant. Wilkins later transferred to the general list and in 1918 was appointed as an official war photographer. In June 1918 Wilkins was awarded theMilitary Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

for his efforts to rescue wounded soldiers during the Third Battle of Ypres. He remains the only Australian official photographer from any war to have received a combat medal. The following month Wilkins was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

and became officer commanding No.3 (Photographic) Sub-section of the Australian war records unit.

Wilkins's work frequently led him into the thick of the fighting and during the Battle of the Hindenburg Line he assumed command of a group of American soldiers who had lost their officers in an earlier attack, directing them until support arrived. Wilkins was subsequently awarded a bar to his Military Cross in the 1919 Birthday Honours.

When Australian WWI general Sir John Monash was asked by the visiting American journalist Lowell Thomas

Lowell Jackson Thomas (April 6, 1892 – August 29, 1981) was an American writer, Television presenter, broadcaster, and documentary filmmaker. He authored more than fifty non-fiction books, mostly travel narratives and popular biographies of ex ...

(who had written '' With Lawrence in Arabia'' and made T. E. Lawrence an international hero) if Australia had a similar hero, Monash spoke of Wilkins: "Yes, there was one. He was a highly accomplished and absolutely fearless combat photographer. What happened to him is a story of epic proportions. Wounded many times ... he always came through. At times he brought in the wounded, at other times he supplied vital intelligence of enemy activity he observed. At one point he even rallied troops as a combat officer ... His record was unique."

Early career and personal life

After the war, Wilkins served in 1921–22 as an

After the war, Wilkins served in 1921–22 as an ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

aboard the ''Quest

A quest is a journey toward a specific mission or a goal. It serves as a plot device in mythology and fiction: a difficult journey towards a goal, often symbolic or allegorical. Tales of quests figure prominently in the folklore of every nat ...

'' on the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition to the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

and adjacent islands.

Wilkins in 1923 began a two-year study for the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

of the bird life of Northern Australia. This ornithology project occupied his life until 1925. His work was greatly acclaimed by the museum but derided by Australian authorities because of the sympathetic treatment afforded to Indigenous Australians and criticisms of the ongoing environmental damage in the country.

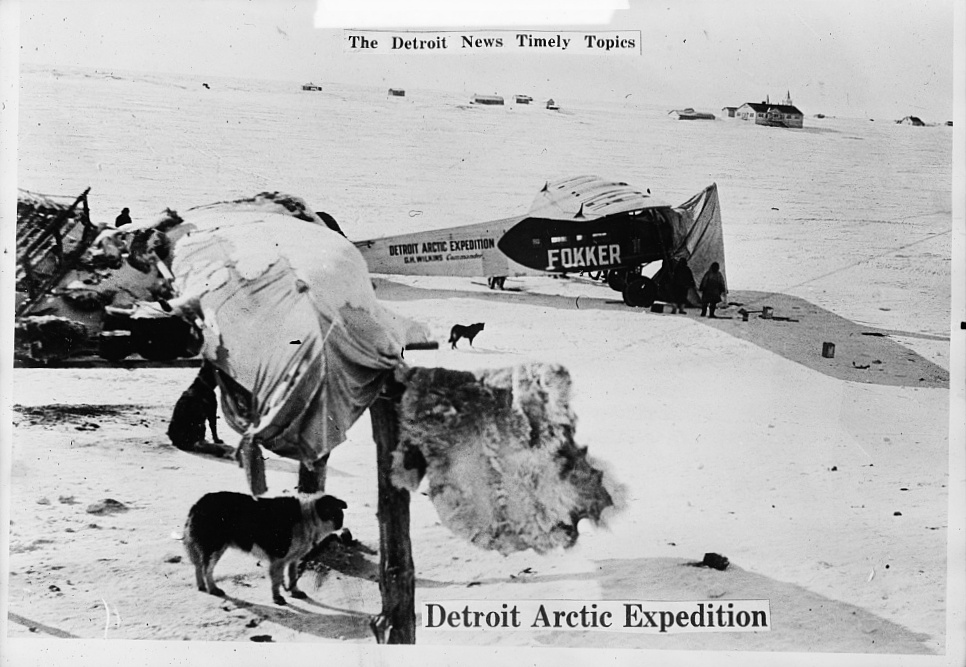

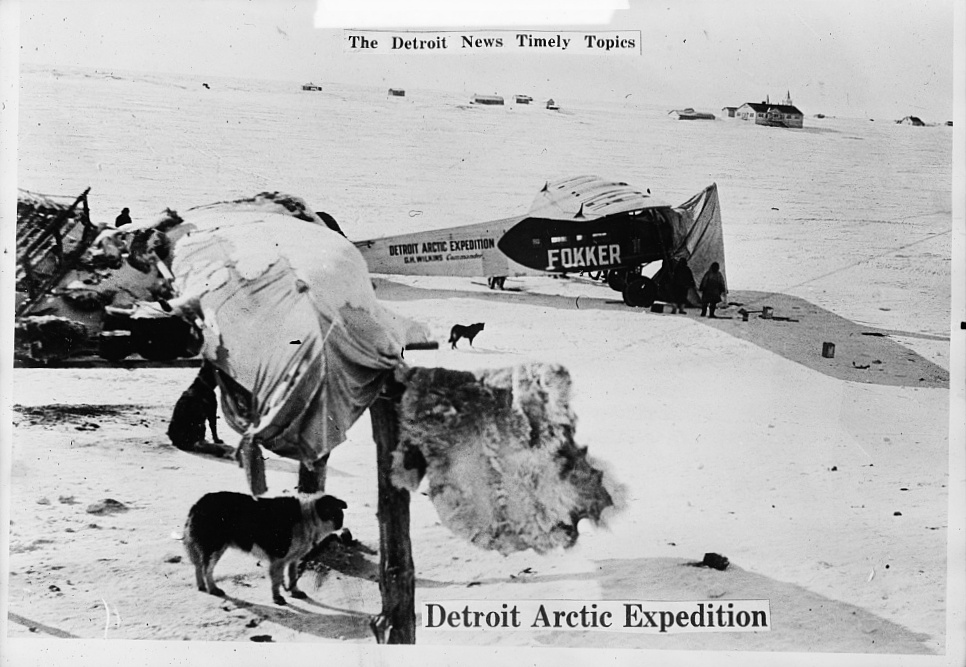

In March 1927, Wilkins and pilot Carl Ben Eielson explored the drift ice north of Alaska, touching down upon it in Eielson's airplane in the first land-plane descent onto drift ice. Soundings taken at the landing site indicated a water depth of 16,000 feet, and Wilkins hypothesized from the experience that future Arctic expeditions would take advantage of the wide expanses of open ice to use aircraft in exploration. In December 1928, Wilkins and Eielson took off from Deception Island, one of Antarctic's most remote islands, and made the first successful airplane flight over the continent.

Wilkins was the first recipient of the Samuel Finley Breese Morse Medal, which was awarded to him by the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are United States, Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows f ...

in 1928."The Cullum Geographical Medal". American Geographical Society. Retrieved 17 June 2010. He was also awarded the

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

's Patron's Medal the same year.

On 15 April 1928, a year after Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, and author. On May 20–21, 1927, he made the first nonstop flight from New York (state), New York to Paris, a distance of . His aircra ...

's flight across the Atlantic, Wilkins and Eielson made a trans-Arctic crossing from Point Barrow, Alaska, to Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

, arriving about 20 hours later on 16 April, touching along the way at Grant Land on Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

. For this feat and his prior work, Wilkins was knighted, and during the ensuing celebration in New York, he met an Australian actress, Suzanne Bennett, whom he later married.

Now financed by William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

, Wilkins continued his polar explorations, flying over Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

in the ''San Francisco''. He named the island of Hearst Land after his sponsor, and Hearst thanked Wilkins by giving him and his bride a flight aboard '' Graf Zeppelin''.

Wilkins was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in 1930.

''Nautilus'' expedition

Preparations

In 1930 Wilkins and his wife, Suzanne, were vacationing with a wealthy friend and colleagueLincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth (May 12, 1880 – May 26, 1951) was an American polar explorer, engineer, surveyor, and author. He led the first Arctic and Antarctic air crossings.

Early life

Linn Ellsworth was born in Chicago, Illinois on May 12, 1880. His ...

. During this outing Wilkins and Ellsworth hammered out plans for a trans-Arctic expedition involving a submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

. Wilkins said the expedition was meant to conduct a "comprehensive meteorology study" and collect "data of academic and economic interest". He also anticipated Arctic weather stations and the potential to forecast Arctic weather "several years in advance". Wilkins believed a submarine could take a fully equipped laboratory into the Arctic.

Expedition

The expedition suffered losses before they even left New York Harbor. Quartermaster Willard Grimmer was knocked overboard and drowned in the harbor. Wilkins was undaunted and drove on with preparations for a series of test cruises and dives before they were to undertake their trans-Arctic voyage. Wilkins and his crew made their way up the Hudson River to Yonkers, eventually reachingNew London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

, where additional modifications and test dives were performed. Satisfied with the performance of both the machinery and the crew, Wilkins and his men left the relative safety of coastal waterways for the uncertainty of the North Atlantic on 4 June 1931.

Soon after the commencement of the expedition the starboard engine broke down, and soon after that the port engine followed suit. On 14 June 1931 without a means of propulsion Wilkins was forced to send out an SOS and was rescued later that day by the USS ''Wyoming''. The ''Nautilus'' was towed to Ireland on 22 June 1931, and was taken to England for repairs.

On 28 June the ''Nautilus'' was up and running and on her way to Norway to pick up the scientific contingent of their crew. By 23 August they had left Norway and were only 600 miles from the North Pole. It was at this time that Wilkins uncovered another setback. His submarine was missing its diving planes. Without diving planes he would be unable to control the ''Nautilus'' while submerged.

Wilkins was determined to do what he could without the diving planes. For the most part Wilkins was thwarted from discovery under the ice floes. The crew was able to take core samples of the ice, as well as testing the salinity of the water and gravity near the pole.

Wilkins had to acknowledge that his adventure into the Arctic was becoming too foolhardy when he received a wireless plea from Hearst which said, "I most urgently beg of you to return promptly to safety and to defer any further adventure to a more favorable time, and with a better boat."

Wilkins ended the first expedition to the poles in a submarine and headed for England, but was forced to take refuge in the port of Bergen, Norway, because of a fierce storm that they encountered en route. The ''Nautilus'' suffered serious damage that made further use of the vessel unfeasible. Wilkins received permission from the United States Navy to sink the vessel off shore in a Norwegian fjord on 20 November 1931.

Despite the failure to meet his intended objective, he was able to prove that submarines were capable of operating beneath the polar ice cap, thereby paving the way for future successful missions.

Later life and career

Wilkins became a student of '' The Urantia Book'' and supporter of the Urantia movement after joining the '70' group in Chicago in 1942. After the book's publication in 1955, he 'carried the massive work on his long travels, even to the Antarctic' and told associates that it was his religion. On 16 March 1958, Wilkins appeared as a guest on the TV panel show ''What's My Line?

''What's My Line?'' is a Panel show, panel game show that originally ran in the United States, between 1950 and 1967, on CBS, originally in black and white and later in color, with subsequent American revivals. The game uses celebrity panelists ...

''

Death and legacy

Wilkins died inFramingham, Massachusetts

Framingham () is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston ...

, on 30 November 1958. The US Navy later took his ashes to the North Pole aboard the submarine USS ''Skate'' on 17 March 1959. The Navy confirmed on 27 March that, "In a solemn memorial ceremony conducted by Skate shortly after surfacing, the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkins were scattered at the North Pole in accordance with his last wishes."

The Wilkins Sound, Wilkins Coast

Wilkins Coast is that portion of the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula between Cape Agassiz and Cape Boggs.

Name

Wilkins Coast was named by the United States Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) for Sir Hubert Wilkins, who in a pion ...

, the Wilkins Runway aerodrome and the Wilkins Ice Shelf in Antarctica are named after him, as are the airport at Jamestown, South Australia

Jamestown is a town in the Mid North region of South Australia north of Adelaide. It lies on the banks of the Belalie Creek and on the Crystal Brook-Broken Hill railway line between Gladstone railway station, South Australia, Gladstone and Peter ...

, and Sir Hubert Wilkins Road at Adelaide Airport

Adelaide Airport, also known as Adelaide International Airport, is an International airport, international, Domestic airport, domestic and general aviation airport serving Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. Located approximately 6 km ...

. The majority of Wilkins's papers and effects are archived at The Ohio State University

The Ohio State University (Ohio State or OSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio, United States. A member of the University System of Ohio, it was founded in 1870. It is one ...

Byrd Polar Research Center.

A species of Australian skink

Skinks are a type of lizard belonging to the family (biology), family Scincidae, a family in the Taxonomic rank, infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one o ...

, '' Lerista wilkinsi'', is named after him,Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). ''The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. . ("Wilkins", pp. 285-286).

as is a species of rock wallaby, '' Petrogale wilkinsi'', first described in 2014.

He is briefly portrayed by actor John Dease in the film '' Smithy'' (1946).

Works

* 1917 * 1928 * 1928 * 1931 * 1942 with Harold M. Sherman: ''Thoughts Through Space'', Creative Age Press. Republished asSee also

* Thomas George Lanphier, Sr.References

Further reading

* * * ''Voyage of the Nautilus'', Documentary 2006, AS Videomaker/Real Pictures * * *External links

Australian War Memorial

Entry for Sir George Hubert Wilkins

biography from Flinders Ranges Research

Short bio on Sir Hubert Wilkins

Searching for Sir Hubert

Documentary Filmmaker site

''Life&Times'' radio documentary, first broadcast by ABC Radio National, 29 August 2009 *

The Papers of George Hubert Wilkins

at Dartmouth College Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkins, George Hubert 1888 births 1958 deaths Australian aviators Australian polar explorers Australian military personnel of World War I Australian ornithologists Australian photographers Australian Knights Bachelor Ohio State University faculty People from Hallett, South Australia Explorers of the Arctic Australian recipients of the Military Cross 20th-century Australian zoologists Members of the American Philosophical Society