History Of Washington, D.C. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

/ref> The final site was just below the

The center of the square is within the grounds of the

"Major Peter Charles L'Enfant"

and a

in its histories of the

''in'

"Washington, D.C., A National Register of Historic Places Travel Inventory"

''in'

official website of the U.S. National Park Service

Accessed August 14, 2008. In 1800, the seat of the

During the

During the

A portion of the

A portion of the

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War, Lincoln was shot in

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War, Lincoln was shot in

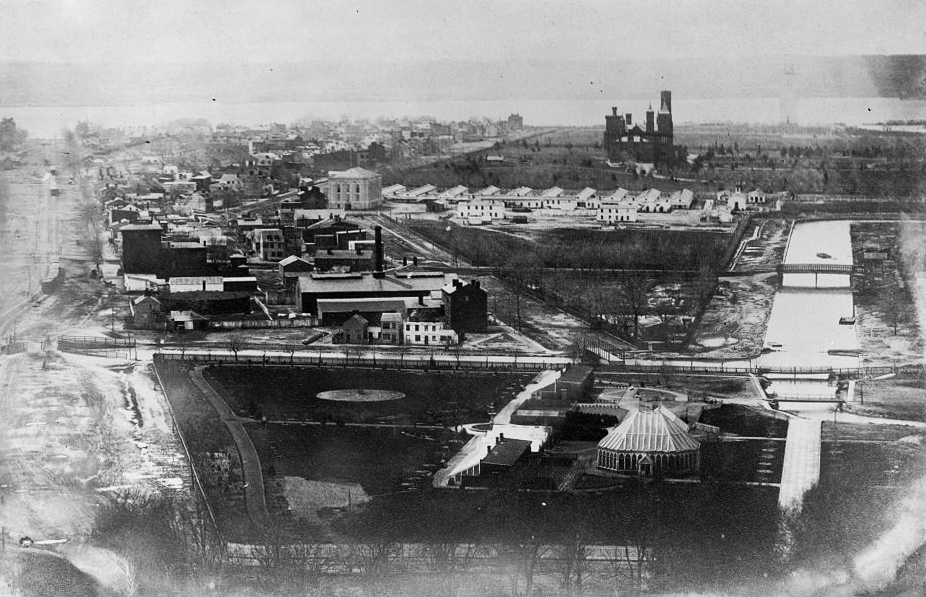

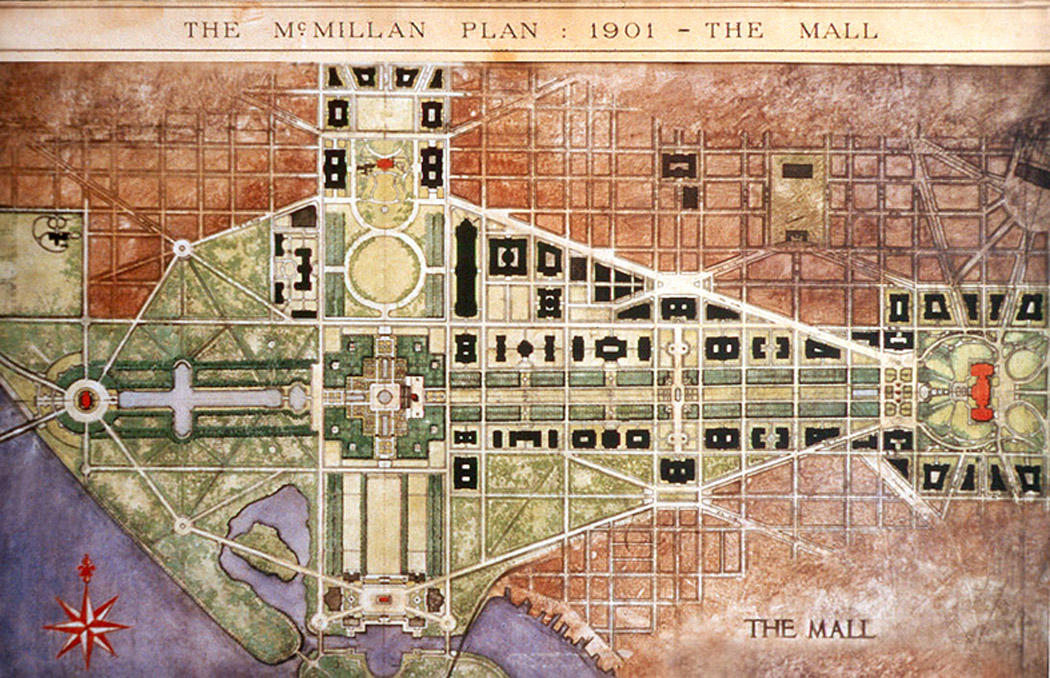

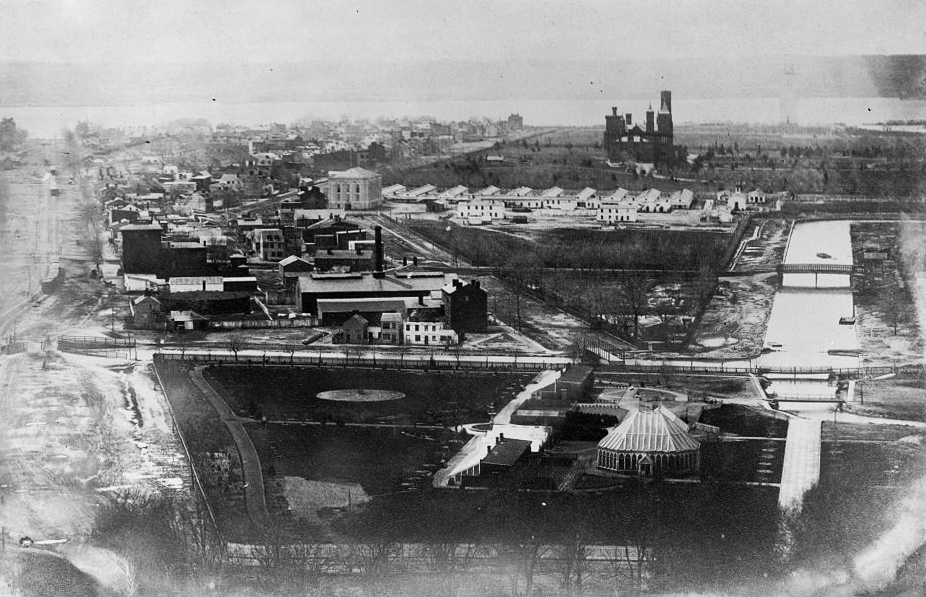

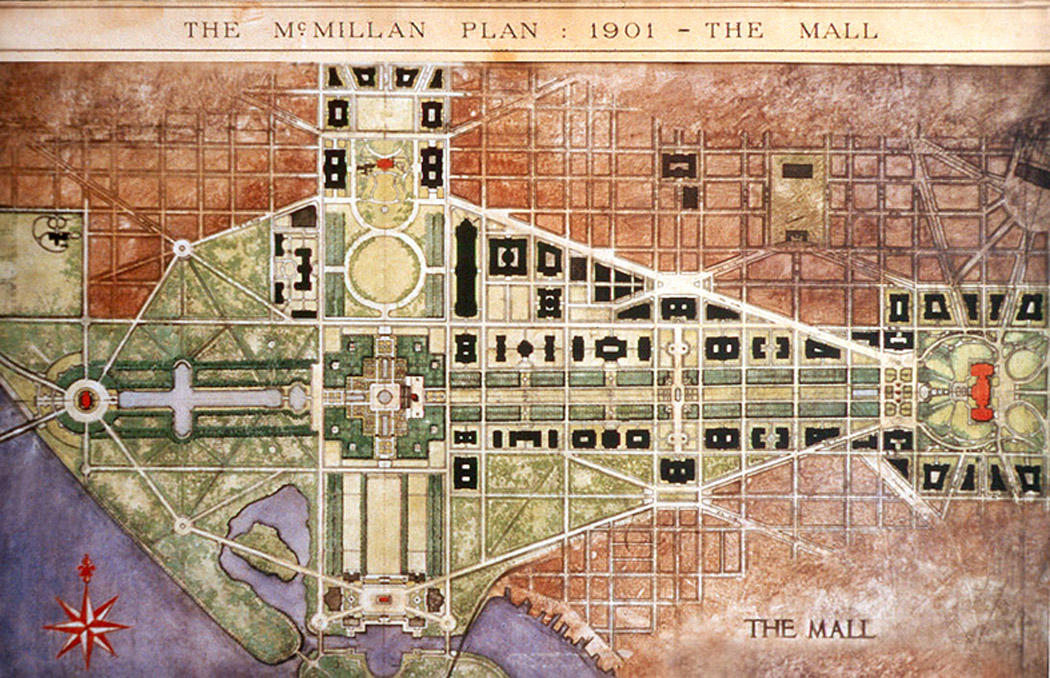

In 1901, the

In 1901, the

The city experienced a brief intensification of racial segregation in 1944 after the appointment of Senator Theodore G. Bilbo, a radical segregationist

The city experienced a brief intensification of racial segregation in 1944 after the appointment of Senator Theodore G. Bilbo, a radical segregationist

In 2021, right-wing demonstrators gathered at a rally in support of President

In 2021, right-wing demonstrators gathered at a rally in support of President

online

* Borchert, James. ''Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religion, and Folklife in the City, 1850–1970'' (U of Illinois Press, 1980). * * Clark-Lewis, Elizabeth, ed. ''First Freed: Washington, D.C., in the Emancipation Era'' (Howard University Press, 2002) Se

online review

* Clark-Lewis, Elizabeth. ''Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics in Washington, D.C., 1910–1940'' (2010) * * Fauntroy, Michael K. ''Home Rule or House Rule: Congress and the Erosion of Local Governance in the District of Columbia'' (University Press of America, 2003) * Gilbert, Ben W. ''Ten Blocks from the White House: Anatomy of the Washington Riots of 1968'' (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1968). * Goode, James M. ''The outdoor sculpture of Washington, DC: A comprehensive historical guide'' (George Braziller, 1974) *Green, Constance McL. '' Washington: A History of the Capital'' (Princeton U.P. 2 vol 1976) comprehensive scholarly history

online

* Green, Constance McL. ''Secret City: History of Race Relations in the Nation's Capital'' (1969

online

* Harrison, Robert. ''Washington during Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism'' (Cambridge University Press, 2011) 343pp

online review

* Jaffe, Harry. ''Dream City: Race, Power, and the Decline of Washington'' (Simon & Schuster, 1994) * Lessoff, Alan. ''The Nation and Its City: Politics, "Corruption," and Progressive in Washington, D.C., 1861–1902'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994) * Lewis, Tom. ''Washington: A History of Our National City'' (New York: Basic, 2015). xxx, 521 pp. * Masur, Kate. ''An Example for all the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C.'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2010). * Ovason, David. ''The Secret Architecture of Our Nation's Capital: the Masons and the building of Washington, D.C.'' (2002). * Roe, Donald. "The Dual School System in the District of Columbia, 1862–1954: Origins, Problems, Protests," ''Washington History,'' 16#2 (Fall/Winter 2004–05), 26–43. * Sandage, Scott A. "A Marble House Divided: The Lincoln Memorial, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Politics of Memory, 1939–1963," ''Journal of American History,'' 80#1 (1993), 135–167

in JSTOR

* Savage, Kirk. ''Monument wars: Washington, DC, the national mall, and the transformation of the memorial landscape'' (U of California Press, 2009) * * Smith, Sam. ''Captive Capital: Colonial Life in Modern Washington'' (1974) * Solomon, Burt. ''The Washington Century: Three Families and the Shaping of the Nation's Capital'' (HarperCollins, 2004). * Terrell, Mary Church. "History of the High School for Negroes in Washington," ''Journal of Negro History'' 2#3 (1917), 252–266

in JSTOR

* Winkle, Kenneth J. ''Lincoln's Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, DC'' (2013)

The Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

* ttp://www.h-net.org/~dclist/ Washington D.C. history discussion list on H-Netbr>Ghosts of DC – A Washington, D.C. history blog

*

*Ovason, David

''The Secret Architecture of Our Nation's Capital: the Masons and the building of Washington, D.C.''

New York City: Perennial, 2002. *

Segregation Incorporated

a 1949 presentation by

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, is tied to its role as the capital of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. The site of the District of Columbia along the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

was first selected by President George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

. The city came under attack during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

Upon the government's return to the capital, it had to manage the reconstruction of numerous public buildings, including the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

and the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

. The McMillan Plan

The McMillan Plan (formally titled The Report of the Senate Park Commission. The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia) is a comprehensive planning document for the development of the monumental core and the park system of Was ...

of 1901 helped restore and beautify the downtown core area, including establishing the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institu ...

, along with numerous monuments and museums.

Relative to other major cities with a high percentage of African Americans, Washington, D.C. has had a significant black population since the city's creation. As a result, Washington became both a center of African American culture

African-American culture, also known as Black American culture or Black culture in American English, refers to the cultural expressions of African Americans, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. African-American/Bl ...

and a center of the civil rights movement. Since the city government was run by the U.S. federal government, black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

and white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

school teachers were paid at an equal scale as workers for the federal government. It was not until the administration of Woodrow Wilson, a Southern Democrat who had numerous Southerners in his cabinet, that federal offices and workplaces were segregated, starting in 1913. This situation persisted for decades: the city was racially segregated in certain facilities until the 1950s.

Neighborhoods on the eastern periphery of the central city and east of the Anacostia River

The Anacostia River is a river in the Mid-Atlantic states, Mid Atlantic region of the United States. It flows from Prince George's County, Maryland, Prince George's County in Maryland into Washington, D.C., where it joins with the Washington Ch ...

tend to be disproportionately lower-income. Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, many middle-income whites moved out of the city's central and eastern sections to newer, affordable suburban housing, with commuting eased by highway construction. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an American civil rights activist, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:05& ...

in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

on April 4, 1968, sparked major riots in chiefly African American neighborhoods east of Rock Creek Park

Rock Creek Park is a large urban park that bisects the Northwest, Washington, D.C., Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. Created by Act of Congress in 1890, the park comprises 1,754 acres (2.74 mi2, 7.10 km2), generally along Rock Cr ...

. Large sections of the central city remained blighted for decades. Areas west of the Park, including virtually the entire portion of the District between the Georgetown and Chevy Chase

Cornelius Crane "Chevy" Chase (; born October 8, 1943) is an American comedian, actor, and writer. He became the breakout cast member in the first season of ''Saturday Night Live'' (1975–1976), where his recurring ''Weekend Update'' segment b ...

neighborhoods, include some of the nation's most affluent and notable neighborhoods. During the early 20th century, the U Street Corridor served as an important center for African American culture in the city. The Washington Metro

The Washington Metro, often abbreviated as the Metro and formally the Metrorail, is a rapid transit system serving the Washington metropolitan area of the United States. It is administered by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority ...

opened in 1976. A rising economy and gentrification

Gentrification is the process whereby the character of a neighborhood changes through the influx of more Wealth, affluent residents (the "gentry") and investment. There is no agreed-upon definition of gentrification. In public discourse, it has ...

in the late 1990s and early 2000s led to the revitalization of many downtown neighborhoods

A neighbourhood (Commonwealth English) or neighborhood (American English) is a geographically localized community within a larger town, city, suburb or rural area, sometimes consisting of a single street and the buildings lining it. Neighbourh ...

.

Article One, Section 8, of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

places the District, which is not a state, under the exclusive legislation of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. Throughout its history, Washington, D.C. residents have therefore lacked voting representation in Congress. The Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Twenty-third Amendment (Amendment XXIII) to the United States Constitution extends the right to participate in presidential elections to the District of Columbia. The amendment grants to the district electors in the Electoral College, as ...

, ratified in 1961, gave the District three electoral votes, implicitly authorisizing it to hold an election for president and vice president. The 1973 District of Columbia Home Rule Act

The District of Columbia Home Rule Act is a United States federal law passed on December 24, 1973, which devolved certain congressional powers of the District of Columbia to local government, furthering District of Columbia home rule. In par ...

provided the local government more control of affairs, including direct election of the city council

A municipal council is the legislative body of a municipality or local government area. Depending on the location and classification of the municipality it may be known as a city council, town council, town board, community council, borough counc ...

and mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a Municipal corporation, municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilitie ...

.

Early settlement

Archaeological evidence indicates Native American Indian tribes relocated to the area at least 4,000 years ago, where they settled around theAnacostia River

The Anacostia River is a river in the Mid-Atlantic states, Mid Atlantic region of the United States. It flows from Prince George's County, Maryland, Prince George's County in Maryland into Washington, D.C., where it joins with the Washington Ch ...

. Early European exploration of the region took place early in the 17th century, including explorations by Captain John Smith in 1608.

At the time, the Patawomeck

The Patawomeck are a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identif ...

, loosely affiliated with the Powhatan

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powh ...

, and the Doeg lived on the Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

side of present-day Washington, D.C. and on Theodore Roosevelt Island, and the Piscataway, also known as Conoy tribe of Algonquians, resided on the Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

side. Native inhabitants within present-day Washington, D.C., included the Nacotchtank, at Anacostia

Anacostia is a historic neighborhood in Southeast (Washington, D.C.), Southeast Washington, D.C. Its downtown is located at the intersection of Marion Barry Avenue (formerly Good Hope Road) SE and the neighborhood contains commercial and gover ...

, who were affiliated with the Conoy. Another village was located between Little Falls and Georgetown, and English fur trader Henry Fleet documented a Nacotchtank village called Tohoga on the site of present-day Georgetown.

The first colonial-era landowners in the present-day Washington, D.C. were George Thompson and Thomas Gerrard, who were granted the Blue Plains tract in 1662, along with Saint Elizabeth, and other tracts in Anacostia, Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill is a neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood in Washington, D.C., located in both the Northeast, Washington, D.C., Northeast and Southeast, Washington, D.C., Southeast quadrants. It is bounded by 14th Street SE & NE, F S ...

, and other areas down to the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

in the following years. Thompson sold his Capitol Hill properties in 1670, including Duddington Manor, to Thomas Notley. The Duddington property was handed down over the generations to Daniel Carroll of Duddington. As European settlers arrived, they clashed with the Native Americans over grazing rights.

In 1697, the colonial-era Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ...

authorized the building of a fort within what is now Washington, D.C. The same year, the Conoy relocated to the west, near what is now The Plains, Virginia, and in 1699 they moved again to Conoy Island near Point of Rocks, Maryland

Point of Rocks is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Frederick County, Maryland. As of the 2010 United States census, 2010 census, it had a population of 1,466.

Point of Rocks is named for a roc ...

.

Georgetown was established in 1751 when the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives, and the lower ...

purchased sixty acres of land for the town from George Gordon and George Beall at the price of £280, while Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

was founded in 1749.

Situated on the fall line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is noticeable especially the place rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the ...

, Georgetown was the farthest point upstream to which oceangoing boats could navigate the Potomac River. The strong flow of the Potomac kept a navigable channel clear year-round, and the daily tidal lift of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

raised the Potomac's elevation in its lower reach such that fully laden ocean-going ships could navigate easily, all the way to Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. Around 1745, Gordon constructed a tobacco inspection house along the Potomac River.

Warehouses, wharves, and other buildings were added, and the settlement rapidly grew. Old Stone House in present-day Georgetown, was built in 1765 and is the oldest standing building in Washington, D.C. Georgetown later grew into a thriving port, facilitating trade and shipments of tobacco and other goods from the colonial-era Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ...

.

In 1780, with the economic and population growth in Georgetown, Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private Jesuit research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789, it is the oldest Catholic higher education, Ca ...

was founded, drawing students from as far away as the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

.

Founding

Establishment

The United States capital was originally located inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, beginning with the First and Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

, followed by the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States from March 1, 1781, until March 3, 1789, during the Confederation ...

upon ratification of the first federal constitution. In June 1783, a mob of angry soldiers converged upon Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence, Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States were debated and adopted by the Founding Fathers of ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

to demand payment for their service during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Congress requested that John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13, O.S. November 2">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. November 21732Various sources indicate a birth date of November 8, 12 or 13, but his most recent biographer ...

, the governor of Pennsylvania

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

, call up the militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

to defend Congress from attacks by the protesters.

In what became known as the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783

The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 (also known as the Philadelphia Mutiny) was an anti-government protest by nearly 400 soldiers of the Continental Army in June 1783. The mutiny, and the refusal of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania to stop i ...

, Dickinson sympathized with the protesters and refused to remove them from Philadelphia. As a result, Congress was forced to flee to Princeton, New Jersey

The Municipality of Princeton is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton, New Jersey, Borough of Princeton and Pri ...

, on June 21, 1783.

On October 6, 1783, while still in Princeton, Congress resolved itself into a committee of the whole to consider a place for the permanent residence of Congress. The following day, Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry ( ; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death i ...

of Massachusetts motioned "that buildings for the use of Congress be erected on the banks of the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

near Trenton or of the Potomac, near Georgetown, provided a suitable district can be procured on one of the rivers as aforesaid, for a federal town". Dickinson's failure to protect the institutions of the national government was discussed at the Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. While the convention was initially intended to revise the league of states and devise the first system of federal government under the Articles of Conf ...

in 1787 In Article One, Section 8, of the United States Constitution, the delegates granted Congress the power:

To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of Particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of theGovernment of the United States The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States. The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ..., and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards and other needful Buildings;

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, writing in Federalist No. 43, also argued that the national capital needed to be distinct from the states, to provide for its own maintenance and safety. The Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, however, does not select a specific site for the location of the new District.

Proposals from the legislatures of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

all offered territory for the national capital location. Northern states preferred a capital located in one of the nation's prominent cities, unsurprisingly, almost all of which were in the north. Southern states, on the other hand, preferred that the capital be located closer to their agricultural and slave-holding interests. The selection of the area around the Potomac River, which was the boundary between Maryland and Virginia, both slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

, was agreed upon between Madison, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

. Hamilton had a proposal for the new federal government to take over debts accrued by the states during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. However, by 1790, Southern states had largely repaid their overseas debts. Hamilton's proposal would require Southern states to assume a share of Northern debt. Jefferson and Madison agreed to this proposal and, in return, secured a Southern location for the federal capital.

On December 23, 1788, the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives, and the lower ...

passed an act, allowing it to cede land for the federal district. The Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, ...

followed suit on December 3, 1789. The signing of the federal Residence Act

The Residence Act of 1790, officially titled An Act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States (), is a United States federal statute adopted during the second session of the 1st United States Cong ...

on July 16, 1790, mandated that the site for the permanent seat of government, "''not exceeding ten miles square''" (100 square miles), be located on the "river Potomack, at some place between the mouths of the Eastern-Branch and Connogochegue". The "Eastern-Branch" is known today as the Anacostia River

The Anacostia River is a river in the Mid-Atlantic states, Mid Atlantic region of the United States. It flows from Prince George's County, Maryland, Prince George's County in Maryland into Washington, D.C., where it joins with the Washington Ch ...

. The Conococheague Creek

Conococheague Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River, is a free-flowing stream that originates in Pennsylvania and empties into the Potomac River near Williamsport, Maryland, Williamsport, Maryland. It is in length,U.S. Geological Survey. Natio ...

empties into the Potomac River upstream near Williamsport and Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in Washington County, Maryland, United States, and its county seat. The population was 43,527 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Hagerstown ranks as Maryland's List of municipalities in Maryland, sixth-most popu ...

. The Residence Act limited to the Maryland side of the Potomac River the location of land that commissioners appointed by the President could acquire for federal use.

The Residence Act authorized President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

to select the actual location of the site. However, he wished to include Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

, within the federal district. To accomplish this, the boundaries of the federal district would need to encompass an area on the Potomac that was downstream of the mouth of the Eastern Branch.

The U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

amended the Residence Act in 1791 to permit Alexandria's inclusion in the federal district. However, some members of Congress had recognized that Washington and his family owned property in and near Alexandria, which was just upstream from Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

, Washington's home and plantation. The amendment, therefore, contained a provision that prohibited the "''erection of the public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the river Potomac''".Hazleton, p. 4/ref> The final site was just below the

fall line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is noticeable especially the place rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the ...

on the Potomac River, the furthest inland point navigable by boats. It included the ports of Georgetown and Alexandria. The process of establishing the federal district, however, faced other challenges in the form of strong objections from landowners such as David Burnes

David "Davy" Burnes, his surname is also spelled Burns (1739–1799), made a fortune selling his land to help create the City of Washington. The White House, South Lawn, The Ellipse, and part of the National Mall sit on land that Burnes once owned. ...

, who owned a large, tract of land in the heart of the district. On March 30, 1791, Burns and eighteen other key landowners relented and signed an agreement with Washington, where they would be compensated for any land taken for public use, half of the remaining land would be distributed among the proprietor

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as ''title'', which may be separated and held by diffe ...

s, and the other half to the public.

Pursuant to the Residence Act, President Washington appointed three commissioners ( Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll

Daniel Carroll Jr. (July 22, 1730May 7, 1796) was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, a Maryland politician, and a plantation owner. He supported the American Revolution, served in the Confederation Congress, was a delegate to ...

, and David Stuart) in 1791 to supervise the planning, design, and acquisition of property in the federal district and capital city. In September 1791, using the toponym Columbia and the name of the president, the three commissioners agreed to name the federal district as the Territory of Columbia, and the federal city as the City of Washington.

On March 30, 1791, President Washington issued a presidential proclamation that established " Jones's point, the upper cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

of Hunting Creek in Virginia" as the starting point for the federal district's boundary survey. The proclamation also described the method by which the survey should determine the district's boundaries. Working under the general supervision of the three commissioners and at the direction of President Washington, Major Andrew Ellicott, assisted by his brothers Benjamin

Benjamin ( ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the younger of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel, and Jacob's twe ...

and Joseph Ellicott, Isaac Roberdeau, Isaac Briggs, George Fenwick, and, initially, an African American astronomer, Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker (November 9, 1731October 19, 1806) was an American Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author. A Land tenure, landowner, he also worked as a surveying, surveyor and farmer.

Born in Baltimore Co ...

, then proceeded to survey the borders of the Territory of Columbia with Virginia and Maryland during 1791 and 1792.

The survey team enclosed within a square an area containing the full that the Residence Act had authorized. Each side of the square was long. The axes

Axes, plural of ''axe'' and of ''axis'', may refer to

* ''Axes'' (album), a 2005 rock album by the British band Electrelane

* a possibly still empty plot (graphics)

See also

* Axis (disambiguation)

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics ...

between the corners of the square ran north–south and east–west.Digital LibraryThe center of the square is within the grounds of the

Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

headquarters west of the Ellipse

The Ellipse, sometimes referred to as President's Park South, is a park south of the White House fence and north of Constitution Avenue and the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. The Ellipse is also the name of the circumference ...

.

The survey team placed forty sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

boundary marker

A boundary marker, border marker, boundary stone, or border stone is a robust physical marker that identifies the start of a land Border, boundary or the change in a boundary, especially a change in direction of a boundary. There are several ...

s at or near every mile point along the sides of the square. Thirty-six of these markers still remain. The south cornerstone is at Jones Point. The west cornerstone is at the west corner of Arlington County, Virginia

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county is located in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C., the nati ...

. The north cornerstone is south of East-West Highway near Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially Unincorporated area, unincorporated, it is an edge city with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 ...

, west of 16th Street. The east cornerstone is east of the intersection of Southern Avenue and Eastern Avenue.

On January 1, 1793, Andrew Ellicott submitted to the commissioners a report that stated that the boundary survey had been completed and that all of the boundary marker stones had been set in place. Ellicott's report described the marker stones and contained a map that showed the boundaries and topographical features of the Territory of Columbia. The map identified the locations within the Territory of the planned City of Washington and its major streets and the location of each boundary marker stone.

Plan of the City of Washington

In early 1791, PresidentGeorge Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, in preparation for the move of the national capital from Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, appointed Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant to devise a plan for the new city in an area of land at the center of the federal territory that lay between the northeast shore of the Potomac River and the northwest shore of the Potomac's Eastern Branch. Facsimile

A facsimile (from Latin ''fac simile'', "to make alike") is a copy or reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or other item of historical value that is as true to the original source as possible. It differs from other forms of r ...

of the 1791 L'Enfant plan ''in'' Repository of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. Note: The plan that this web page describes identifies the plan's author as "Peter Charles L'Enfant". The web page nevertheless identifies the author as "Pierre-Charles L'Enfant." L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life while residing in the United States. He wrote this name on his ''Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States. ... '' (Washington, D.C.) and on other legal documents.

During the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant". (Reference: Bowling, Kenneth R (2002). ''Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic.'' George Washington University, Washington, D.C. ). The National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

has identified L'Enfant a"Major Peter Charles L'Enfant"

and a

in its histories of the

Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States, victorious commander-in-chief of the Continen ...

on its website. The United States Code

The United States Code (formally The Code of Laws of the United States of America) is the official Codification (law), codification of the general and permanent Law of the United States#Federal law, federal statutes of the United States. It ...

states in : "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant." L'Enfant then designed in his "''Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States ... ''" the city's first layout, a grid centered on the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

, which would stand at the top of a hill ( Jenkins Hill) on a longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

designated as 0,0°. The grid filled an area bounded by the Potomac River, the Eastern Branch (now named the Anacostia River

The Anacostia River is a river in the Mid-Atlantic states, Mid Atlantic region of the United States. It flows from Prince George's County, Maryland, Prince George's County in Maryland into Washington, D.C., where it joins with the Washington Ch ...

), the base of an escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations.

Due to the similarity, the term '' scarp'' may mistakenly be incorrectly used inte ...

at the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line along which a street, initially Boundary Street, now Florida Avenue

Florida Avenue is a major street in Washington, D.C. It was originally named Boundary Street, because it formed the northern boundary of the Federal City under the 1791 L'Enfant Plan. With the growth of the city beyond its original borders, B ...

, would later travel, and Rock Creek.

North–south, and east–west streets formed the grid. Wider diagonal "grand avenues" later named after the states of the union crossed the grid. Where these "grand avenues" crossed each other, L'Enfant placed open spaces in circles

A circle is a shape consisting of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the centre. The distance between any point of the circle and the centre is called the radius. The length of a line segment connecting t ...

and plazas that were later named after notable Americans.

L'Enfant's broadest "grand avenue" was a garden-lined esplanade

An esplanade or promenade is a long, open, level area, usually next to a river or large body of water, where people may walk. The historical definition of ''esplanade'' was a large, open, level area outside fortress or city walls to provide cle ...

, which he expected to travel for about along an east–west axis in the center of an area that the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institu ...

now occupies. The narrower Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

connected "Congress house" (the Capitol) with the "President's house" (the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

). In time, Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

developed into the capital city's present "grand avenue".

L'Enfant's plan included a system of canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface ...

s, one of which would travel near the western side of the Capitol at the base of Jenkins Hill. To be filled by the waters of Tiber Creek, also named "Goose Creek", and James Creek

James Creek was a tributary of the Anacostia River in the southwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., once known as St. James' Creek and perhaps named after local landowner James Greenleaf.

It arose from several springs just south of Capitol Hill. ...

, the canal system would traverse the center of the city and entered both the Potomac River and the Eastern Branch.

On June 22, L'Enfant presented his first plan for the federal city to the President. On August 19, he appended a new map to a letter that he sent to the President.

President Washington retained one of L'Enfant's plans, showed it to Congress, and later gave it to the three Commissioners. The survey map may be one that L'Enfant appended to his August 19 letter to the President.

L'Enfant subsequently entered into a number of conflicts with the three commissioners and others involved in the enterprise. During a contentious period in February 1792, Andrew Ellicott, who had been conducting the original boundary survey of the future District of Columbia and the survey of the federal city under the direction of the Commissioners, informed the Commissioners that L'Enfant had not been able to have the city plan engraved and had refused to provide him with the original plan (of which L'Enfant had prepared several versions).Ellicott, Andrew (February 23, 1792). "To Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll and David Stuart, Esqs." ''In''

Ellicott, with the aid of his brother, Benjamin Ellicott, then revised the plan, despite L'Enfant's protests. Ellicott's revisions, which included the straightening of the longer avenues and the removal of Square No. 15 from L'Enfant's original plan, created minor changes to the city's layout.

Ellicott stated in his letters that, although he was refused the original plan, he was familiar with L'Enfant's system and had many notes of the surveys that he had made himself. It is, therefore, possible that Ellicott recreated the plan.

Shortly thereafter, Washington dismissed L'Enfant. Ellicott gave the first version of his own plan to James Thakara and John Vallance of Philadelphia, who engraved, printed, and published it. This version, printed in March 1792, was the first Washington city plan that received wide circulation.

After L'Enfant departed, Ellicott continued the city survey in accordance with his revised plan, several larger and more detailed versions of which were also engraved, published and distributed. As a result, Ellicott's revisions became the basis for the capital city's future development.The L'Enfant and McMillan Plans''in'

"Washington, D.C., A National Register of Historic Places Travel Inventory"

''in'

official website of the U.S. National Park Service

Accessed August 14, 2008. In 1800, the seat of the

federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

was moved to the new city, and on February 27, 1801, the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801

The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, officially An Act Concerning the District of Columbia (6th Congress, 2nd Sess., ch. 15, , February 27, 1801), is an organic act enacted by the United States Congress in accordance with Article 1, S ...

placed the District under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Congress. The act also organized the unincorporated territory within the District into two counties: the County of Washington on the northeast bank of the Potomac and the County of Alexandria on the southwest bank. On May 3, 1802, the City of Washington was granted a municipal government consisting of a mayor appointed by the President of the United States.

19th century

Economic development

The District of Columbia relied on Congress to support capital improvements andeconomic development

In economics, economic development (or economic and social development) is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and object ...

initiatives. However, Congress lacked loyalty to the city's residents and was reluctant to provide support. Congress did provide funding for the Washington City Canal

The Washington City Canal was a canal in Washington, D.C., that operated from 1815 until the mid-1850s. The canal connected the Anacostia River, termed the "Eastern Branch" at that time, to Tiber Creek, the Potomac River, and later the Chesapeak ...

in 1809, after earlier private financing efforts were unsuccessful. Construction began in 1810 and the canal opened in late 1815, connecting the Anacostia River with Tiber Creek.

Construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal and occasionally called the Grand Old Ditch, operated from 1831 until 1924 along the Potomac River between Washington, D.C., and Cumberland, Maryland. It replaced the Patowmack Canal ...

(C&O) began in Georgetown in 1828. Construction westward through Maryland proceeded slowly. The first section, from Georgetown to Seneca, Maryland, opened in 1831. In 1833 an extension was built from Georgetown eastward, connecting to the City Canal. The C&O reached Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a city in Allegany County, Maryland, United States, and its county seat. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 19,075. Located on the Potomac River, Cumberland is a regional business and comm ...

in 1850, although by that time it was obsolete as the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

(B&O) had arrived in Cumberland in 1842. The canal had financial problems, and plans for further construction to reach the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

were abandoned.

War of 1812

During the

During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

conducted an expedition between August 19 and 29, 1814, that took and burned the capital city. In the Battle of Bladensburg

The Battle of Bladensburg, also known as the Bladensburg Races, took place during the Chesapeake Campaign, part of the War of 1812, on 24 August 1814, at Bladensburg, Maryland, northeast of Washington, D.C.

The battle has been described as "t ...

on August 24, the British routed an American militia, which had gathered at Bladensburg, Maryland

Bladensburg is a town in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. The population was 9,657 at the 2020 census. Areas in Bladensburg are located within ZIP code 20710. Bladensburg is from Washington, D.C.

History

Originally called Garr ...

to protect the capital. The militia then abandoned Washington without a fight. President James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

and the remainder of the U.S. government fled the capital shortly before the British arrived.

The British then entered and burned the capital during the most notably destructive raid of the war. British troops set fire to the capital's most important public buildings, including the Presidential Mansion (the White House), the United States Capitol, the Arsenal, the Navy Yard, the Treasury Building, and the War Office, as well as the north end of the Long Bridge

Long may refer to:

Measurement

* Long, characteristic of something of great duration

* Long, characteristic of something of great length

* Longitude (abbreviation: long.), a geographic coordinate

* Longa (music), note value in early music mens ...

, which crossed the Potomac River into Virginia. The British, however, spared the Patent Office

A patent office is a governmental or intergovernmental organization which controls the issue of patents. In other words, "patent offices are government bodies that may grant a patent or reject the patent application based on whether the applicati ...

and the Marine Barracks. Dolley Madison

Dolley Todd Madison (née Payne; May 20, 1768 – July 12, 1849) was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of b ...

, the first lady, or perhaps members of the house staff, rescued the Lansdowne portrait, a full-length painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Stuart ( Stewart; December 3, 1755 – July 9, 1828) was an American painter born in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Rhode Island Colony who is widely considered one of America's foremost portraitists. His best-k ...

, as the British approached the Mansion.

The aftermath of the war kicked off a mild crisis, with many northerners pushing for a relocation of the capitol with a vote brought to the floor of Congress proposing the removal of the government to Philadelphia. It was defeated 83 to 74 votes, and the seat of government remained in Washington, D.C.

Railroads arrive in Washington

TheBaltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

opened a rail line from Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

to Washington in 1835. Passenger traffic on the Washington Branch had increased by the 1850s, as the company opened a large station in 1851 on New Jersey Avenue NW, just north of the Capitol. Further railroad development continued after the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, with a new B&O line, the Metropolitan Branch, connecting Washington, D.C. to the west, and the introduction of competition from the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad

The Baltimore and Potomac Railroad (B&P) operated from Baltimore, Maryland, southwest to Washington, D.C., from 1872 to 1902. Owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad, it was the second railroad company to connect the nation's capital to ...

in the 1870s. In 1907, Washington Union Station

Washington Union Station, known locally as Union Station, is a major train station, transportation hub, and leisure destination in Washington, D.C. Designed by Daniel Burnham and opened in 1907, it is Amtrak's second-busiest station and North ...

opened as the city's central terminal.

Retrocession

Almost immediately after the "Federal City" was laid out north of thePotomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

, some residents south of the Potomac River in Alexandria County, D.C., began petitioning to be returned to Virginia's jurisdiction. Over time, a larger movement grew to separate Alexandria from the District for several reasons:

* Alexandria was a center for slave trading. There was increasing talk of abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

*Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

*Capital punishment#Abolition of capital punishment, Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

*Abolitio ...

of slavery in the national capital. Alexandria's economy would suffer if slavery were outlawed in the District of Columbia. In 1848, then Congressman Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

submitted a bill to abolish slavery within the District, which failed.

* There was an active abolition movement in Virginia; the pro-slavery faction held a slim majority in the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, ...

. If Alexandria and Alexandria County were retroceded to Virginia, they would provide two new pro-slavery representatives.

* Alexandria's economy had stagnated as competition with the port of Georgetown, D.C.

Georgetown is a historic Neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood and commercial district in Northwest (Washington, D.C.), Northwest Washington, D.C., situated along the Potomac River. Founded in 1751 as part of the Colonial history of th ...

, had begun to favor the north side of the Potomac, where most members of Congress and local federal officials resided.

* The Residence Act

The Residence Act of 1790, officially titled An Act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States (), is a United States federal statute adopted during the second session of the 1st United States Cong ...

prohibited federal offices from locating in Virginia.

* The Alexandria Canal, which connected the C&O Canal to Alexandria, needed repairs, which the federal government was reluctant to fund.

After a referendum, Alexandria County's citizens petitioned Congress and Virginia to return the area to Virginia. By an act of Congress on July 9, 1846, and with the approval of the Virginia General Assembly, the area south of the Potomac () was returned, or "retroceded," to Virginia effective in 1847.

The retroceded land, then known as Alexandria County, includes a portion of the independent city

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

of Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and all of Arlington County. A large portion of the retroceded land near the river was an estate of George Washington Parke Custis

George Washington Parke Custis (April 30, 1781 – October 10, 1857) was an American antiquarian, author, playwright, and slave owner. He was a veteran of the War of 1812. His father John Parke Custis served in the American Revolution wi ...

, who had supported the retrocession and helped develop the charter in the Virginia General Assembly for the County of Alexandria, Virginia. The estate, then known as Arlington Plantation, was passed on to his daughter, the wife of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, eventually became Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

.

Civil War era

A portion of the

A portion of the Washington Aqueduct

The Washington Aqueduct is an Aqueduct (water supply), aqueduct that provides the public water supply system serving Washington, D.C., and parts of its suburbs, using water from the Potomac River. One of the first major aqueduct projects in the ...

opened in 1859, providing drinking water

Drinking water or potable water is water that is safe for ingestion, either when drunk directly in liquid form or consumed indirectly through food preparation. It is often (but not always) supplied through taps, in which case it is also calle ...

to city residents and reducing their dependence on well water. The aqueduct built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

opened for full operation in 1864, using the Potomac River as its source.Harry C. Ways, "The Washington Aqueduct: 1852–1992." (Baltimore, MD: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, 1996)

Washington remained a small city of a few thousand residents, virtually deserted during the summertime, until the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

in 1861. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

created the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

to defend the federal capital, and thousands of soldiers came to the area. The significant expansion of the federal government to administer the war—and its legacies, such as veterans' pensions—led to notable growth in the city's population – from 75,000 in 1860 to 132,000 in 1870.

Slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

was abolished throughout the District on April 16, 1862, eight months before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

, with the passage of the Compensated Emancipation Act. The city became a popular place for freed slaves to congregate.

Throughout the Civil War, the city was defended by a ring of Union Army forts that mostly deterred the Confederate army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

from attacking. One notable exception was the Battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864, in which Union soldiers repelled troops under the command of Confederate General Jubal A. Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, ...

. This battle was only the second time a U.S. president came under enemy fire during wartime when Lincoln visited the fort to observe the fighting; the first was James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. Over 20,000 sick and injured Union soldiers were treated in various permanent and temporary hospitals in the capital.

Post-Civil War era

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War, Lincoln was shot in

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1863. The theater is best known for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box where ...

by John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

during the play ''Our American Cousin

''Our American Cousin'' is a three-act play by English playwright Tom Taylor. It is a farce featuring awkward, boorish American Asa Trenchard, who is introduced to his aristocratic English relatives when he goes to England to claim the family e ...

''. The next morning, at 7:22 am, President Lincoln died in the Petersen House

The Petersen House is a 19th-century Federal architecture, federal style row house in the United States in Washington, D.C., located at 516 10th Street NW, several blocks east of the White House. It is known for being the house where President o ...

across the street, the first American president to be assassinated. Following Lincoln's death, then Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

said, "Now he belongs to the ages."

By 1870, the District's population had grown 75% from the previous census to nearly 132,000 residents. Despite the city's growth, Washington still had dirt road

A dirt road or track is a type of unpaved road not paved with asphalt, concrete, brick, or stone; made from the native material of the land surface through which it passes, known to highway engineers as subgrade material.

Terminology

Simi ...

s and lacked basic sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

. The situation was so bad that some members of Congress suggested moving the capital further west, but President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

refused to consider such a proposal.

In response to the poor conditions in the capital, Congress passed the Organic Act of 1871, which revoked the individual charters of the cities of Washington and Georgetown, and created a new territorial government for the whole District of Columbia. The act provided for a governor appointed by the President, a legislative assembly with an upper-house composed of eleven appointed council members and a 22-member house of delegates elected by residents of the District, as well as an appointed Board of Public Works charged with modernizing the city.

President Grant appointed Alexander Robey Shepherd

Alexander Robey Shepherd (January 30, 1835 – September 12, 1902) was an American politician and businessman who was the 2nd Governor of the District of Columbia from 1873 to 1874. He was one of the most controversial and influential civic lead ...

, an influential member of the Board of Public Works, to the post of governor in 1873. Shepherd authorized large-scale municipal projects, which greatly modernized Washington. However, the governor spent three times the money that had been budgeted for capital improvements. He ultimately bankrupted the city. In 1874, Congress abolished the District's territorial government and replaced it with a three-member Board of Commissioners appointed by the President, of which one was a representative from the United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

. The three Commissioners would then elect one of themselves to be president of the commission.

An additional act of Congress in 1878 made the three-member Board of Commissioners the permanent government of the District of Columbia. The act also had the effect of eliminating any remaining local institutions such as the boards on schools, health, and police. The Commissioners would maintain this form of direct rule for nearly a century.

The first motorized streetcars in the District began service in 1888 and spurred growth in areas beyond the City of Washington's original boundaries. In 1888, Congress required that all new developments within the District conform to the layout of the City of Washington. The City of Washington's northern border of Boundary Street was renamed Florida Avenue

Florida Avenue is a major street in Washington, D.C. It was originally named Boundary Street, because it formed the northern boundary of the Federal City under the 1791 L'Enfant Plan. With the growth of the city beyond its original borders, B ...