History Of The United States Marine Corps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

On 3 March 1776, the Continental Marines made their first amphibious landing in American history when they attempted an amphibious assault during the

On 3 March 1776, the Continental Marines made their first amphibious landing in American history when they attempted an amphibious assault during the  Also on the same day 5 June Robert Mullan (whose mother was the proprietor of

Also on the same day 5 June Robert Mullan (whose mother was the proprietor of

Marine Corps History Division

an

At the end of the Revolution on 3 September 1783, both the Continental Navy and Marines were disbanded in April. Although individual Marines stayed on for the few American naval vessels left, the last Continental Marine was discharged in September. In all, there were 131 Colonial Marine officers and probably no more than 2,000 enlisted Colonial Marines. Although individual Marines were enlisted for the few American naval vessels, the organization would not be re-created until 1798. Despite the gap between the disbanding of the Continental Marines and the establishment of the United States Marine Corps, Marines worldwide celebrate 10 November 1775 as the

Due to harassment by the French navy on U.S. shipping during the French Revolutionary Wars, Congress created the

Due to harassment by the French navy on U.S. shipping during the French Revolutionary Wars, Congress created the  The Marine Corps' first land action of the

The Marine Corps' first land action of the

After the war, the Marine Corps fell into a depressed state. The third Commandant, Franklin Wharton, died while in office on 1 September 1818, causing a battle for succession between Majors

After the war, the Marine Corps fell into a depressed state. The third Commandant, Franklin Wharton, died while in office on 1 September 1818, causing a battle for succession between Majors  Henderson secured a confirmed appointment as the fifth commandant in 1820 and breathed new life into the Corps. He would go on to be the longest-serving commandant, commonly referred to as the "Grand old man of the Marine Corps". Under his tenure, the Marine Corps took on a new role as an expeditionary force-in-readiness with a number of expeditionary duties in the Caribbean, the

Henderson secured a confirmed appointment as the fifth commandant in 1820 and breathed new life into the Corps. He would go on to be the longest-serving commandant, commonly referred to as the "Grand old man of the Marine Corps". Under his tenure, the Marine Corps took on a new role as an expeditionary force-in-readiness with a number of expeditionary duties in the Caribbean, the  A decade later, in the

A decade later, in the  In the 1850s, the Marines would further see service in Panama, and in Asia, escorting Matthew C. Perry, Matthew Perry's Black Ships, fleet on its historic trip to the East. Two hundred Marines under Zeilin were among the Americans who first set foot on Japan; they can be seen in contemporary woodprints in their blue jackets, white trousers, and black shakos. Marines were also performed landing demonstrations while the expedition visited the Ryukyu Islands, Ryukyu and Bonin Islands. Upon Henderson's death in 1859, legend cites that he willed the Commandant's House, his home of 38 years, to his heirs, forgetting that it was government property; however, this has proven false.

In the 1850s, the Marines would further see service in Panama, and in Asia, escorting Matthew C. Perry, Matthew Perry's Black Ships, fleet on its historic trip to the East. Two hundred Marines under Zeilin were among the Americans who first set foot on Japan; they can be seen in contemporary woodprints in their blue jackets, white trousers, and black shakos. Marines were also performed landing demonstrations while the expedition visited the Ryukyu Islands, Ryukyu and Bonin Islands. Upon Henderson's death in 1859, legend cites that he willed the Commandant's House, his home of 38 years, to his heirs, forgetting that it was government property; however, this has proven false.

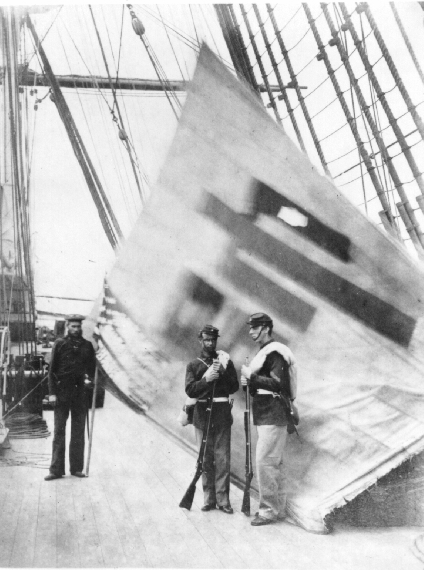

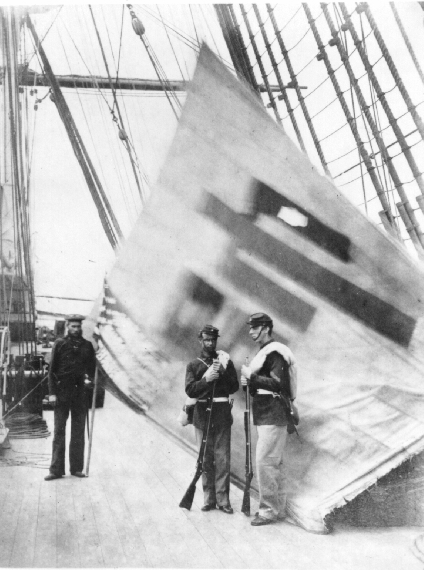

Despite their stellar service in foreign engagements, the Marine Corps played only a minor role during the American Civil War, Civil War (1861–1865); their most important task was blockade duty and other ship-board battles, but were mobilized for a handful of operations as the war progressed.

During the prelude to war, a hastily created 86-man Marine detachment under Lieutenant Israel Greene was detached to arrest John Brown (abolitionist), John Brown at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Harper's Ferry in 1859, after the abolitionist John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, raided the Harpers Ferry Armory, armory there. Command of the mission was given to then-Colonel Robert E. Lee and his aide, Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart, J.E.B. Stuart, both having been on leave in Washington when President James Buchanan ordered Brown arrested. The ninety Marines arrived to the town on 17 October via train, and quickly surrounded John Brown's Fort. Upon his refusal to surrender, the Marines stormed the building with bayonets, battering down the door with hammers and a ladder used as a battering ram. Greene slashed Brown twice and would have killed him had his sword not bent on his last thrust; in his haste he had carried his light dress sword instead of his regulation sword.

Despite their stellar service in foreign engagements, the Marine Corps played only a minor role during the American Civil War, Civil War (1861–1865); their most important task was blockade duty and other ship-board battles, but were mobilized for a handful of operations as the war progressed.

During the prelude to war, a hastily created 86-man Marine detachment under Lieutenant Israel Greene was detached to arrest John Brown (abolitionist), John Brown at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Harper's Ferry in 1859, after the abolitionist John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, raided the Harpers Ferry Armory, armory there. Command of the mission was given to then-Colonel Robert E. Lee and his aide, Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart, J.E.B. Stuart, both having been on leave in Washington when President James Buchanan ordered Brown arrested. The ninety Marines arrived to the town on 17 October via train, and quickly surrounded John Brown's Fort. Upon his refusal to surrender, the Marines stormed the building with bayonets, battering down the door with hammers and a ladder used as a battering ram. Greene slashed Brown twice and would have killed him had his sword not bent on his last thrust; in his haste he had carried his light dress sword instead of his regulation sword.

At the opening of the war, the Marine Corps had 1892 officers and men, but two majors, half the captains, and two-thirds of the lieutenants resigned to join the Confederacy, as did many prominent Army officers. Though the retention of enlisted men was better, the Confederate States Marine Corps formed its nucleus with some of the best Marines the Corps had. Following the wave of defections, thirteen officers and 336 Marines, mostly recruits, were hastily formed into a battalion and sent to Manassas. At the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), U.S. Marines performed poorly, running away like the rest of the Union forces. Commandant John Harris (USMC), John Harris reported sadly that this was "the first instance in Marine history where any portion of its members turned their backs to the enemy". However, "The Marines performed as well as, if not better than, any other Federal organization on the battlefield of 21 July 1861. No regiment in McDowell's army went into the fight more often or with greater spirit than the Marine battalion."

Congress only slightly enlarged the Marines due to the priority of the Army; and after filling detachments for the ships of the Navy (which had more than doubled in size by 1862), the Marine Corps was only able to field about one battalion at any given time as a larger force for service ashore. Marines from ship's detachments as well as ad-hoc battalions took part in the landing operations necessary to capture bases for blockade duty. These were mostly successful, but on 8 September 1863, the Marines tried an Second Battle of Fort Sumter, amphibious landing to capture Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, Charlestown harbor and failed, one of the few failed landings of the Marine Corps. Due to a shortage of officers, the Marines of Commander (United States), Commander George Henry Preble, George Preble's naval brigade that fought at the Battle of Honey Hill in 1864 started the battle with First Lieutenant George Stoddard as the battalion commander (normally accorded a lieutenant colonel), the only officer in the battalion (the company commanders and other Staff (military), staff being sergeants).

At the opening of the war, the Marine Corps had 1892 officers and men, but two majors, half the captains, and two-thirds of the lieutenants resigned to join the Confederacy, as did many prominent Army officers. Though the retention of enlisted men was better, the Confederate States Marine Corps formed its nucleus with some of the best Marines the Corps had. Following the wave of defections, thirteen officers and 336 Marines, mostly recruits, were hastily formed into a battalion and sent to Manassas. At the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), U.S. Marines performed poorly, running away like the rest of the Union forces. Commandant John Harris (USMC), John Harris reported sadly that this was "the first instance in Marine history where any portion of its members turned their backs to the enemy". However, "The Marines performed as well as, if not better than, any other Federal organization on the battlefield of 21 July 1861. No regiment in McDowell's army went into the fight more often or with greater spirit than the Marine battalion."

Congress only slightly enlarged the Marines due to the priority of the Army; and after filling detachments for the ships of the Navy (which had more than doubled in size by 1862), the Marine Corps was only able to field about one battalion at any given time as a larger force for service ashore. Marines from ship's detachments as well as ad-hoc battalions took part in the landing operations necessary to capture bases for blockade duty. These were mostly successful, but on 8 September 1863, the Marines tried an Second Battle of Fort Sumter, amphibious landing to capture Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, Charlestown harbor and failed, one of the few failed landings of the Marine Corps. Due to a shortage of officers, the Marines of Commander (United States), Commander George Henry Preble, George Preble's naval brigade that fought at the Battle of Honey Hill in 1864 started the battle with First Lieutenant George Stoddard as the battalion commander (normally accorded a lieutenant colonel), the only officer in the battalion (the company commanders and other Staff (military), staff being sergeants).

On 15 May 1862, the Battle of Drewry's Bluff began as a detachment of ships under Commander John Rodgers (American Civil War naval officer), John Rodgers (including the and ) steamed up the James River to test the defenses of Richmond, Virginia, Richmond as part of the Peninsula campaign, Peninsula Campaign. As the ''Galena'' took heavy losses, the unwavering musket and cannon fire of Corporal John F. Mackie would earn him the Medal of Honor on 10 July 1863, the first Marine to be so awarded.

In January 1865, the Marines took part in the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, tasked with acting as marksmen on the flank of the attack to shoot any Confederate troops that appeared on the ramparts of the fort. Even though they were ordered from their firing positions by Admiral David Dixon Porter, Porter's second in command, Porter blamed the Marines for the failure of the naval landing force to take the fort. Despite this, the fort was successfully captured; five Marines earned the Medal of Honor during the battle. In all, Marines received 17 of the 1,522 awards during the Civil War. A total of 148 Marines would die in the war, the most casualties up to that point.

On 15 May 1862, the Battle of Drewry's Bluff began as a detachment of ships under Commander John Rodgers (American Civil War naval officer), John Rodgers (including the and ) steamed up the James River to test the defenses of Richmond, Virginia, Richmond as part of the Peninsula campaign, Peninsula Campaign. As the ''Galena'' took heavy losses, the unwavering musket and cannon fire of Corporal John F. Mackie would earn him the Medal of Honor on 10 July 1863, the first Marine to be so awarded.

In January 1865, the Marines took part in the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, tasked with acting as marksmen on the flank of the attack to shoot any Confederate troops that appeared on the ramparts of the fort. Even though they were ordered from their firing positions by Admiral David Dixon Porter, Porter's second in command, Porter blamed the Marines for the failure of the naval landing force to take the fort. Despite this, the fort was successfully captured; five Marines earned the Medal of Honor during the battle. In all, Marines received 17 of the 1,522 awards during the Civil War. A total of 148 Marines would die in the war, the most casualties up to that point.

The remainder of the 19th century would be a period of declining strength and introspection about the mission of the Marine Corps. The Navy's transition from sail to steam put into question the need for Marines on naval ships; indeed, the replacement of masts and rigging with smokestacks literally left Marine marksmen without a place. However, the Marines would serve as a convenient resource for interventions and landings to protect U.S. lives and property in foreign countries, such as the Formosa Expedition, expedition to Taiwan under Qing rule, Formosa in 1867. In June 1871, 651 Marine deployed for the United States expedition to Korea, expedition to Korea and made a landing at Ganghwa Island in which six Marines earned the Medal of Honor and one was killed (landings were also taken by the French expedition to Korea, French in 1866 and Ganghwa Island incident, Japanese in 1875), 79 years before the famed Battle of Inchon, landing at nearby Inchon. After the Virginius Affair caused a war scare with Spain, Marines took part in naval brigade landing exercises in

The remainder of the 19th century would be a period of declining strength and introspection about the mission of the Marine Corps. The Navy's transition from sail to steam put into question the need for Marines on naval ships; indeed, the replacement of masts and rigging with smokestacks literally left Marine marksmen without a place. However, the Marines would serve as a convenient resource for interventions and landings to protect U.S. lives and property in foreign countries, such as the Formosa Expedition, expedition to Taiwan under Qing rule, Formosa in 1867. In June 1871, 651 Marine deployed for the United States expedition to Korea, expedition to Korea and made a landing at Ganghwa Island in which six Marines earned the Medal of Honor and one was killed (landings were also taken by the French expedition to Korea, French in 1866 and Ganghwa Island incident, Japanese in 1875), 79 years before the famed Battle of Inchon, landing at nearby Inchon. After the Virginius Affair caused a war scare with Spain, Marines took part in naval brigade landing exercises in

During the

During the

The successful landing at Guantanamo and the readiness of the Marines for the Spanish–American War were in contrast to the slow mobilization of the United States Army in the war. In 1900, the General Board of the United States Navy decided to give the Marine Corps primary responsibility for the seizure and defense of advanced naval bases. The Marine Corps formed an expeditionary battalion to be permanently based in the Caribbean, which subsequently practiced landings in 1902 in preparation for a war with Germany over their Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903, siege in Venezuela. Under Major Lejeune, in early 1903, it also undertook landing exercises with the Army in

The successful landing at Guantanamo and the readiness of the Marines for the Spanish–American War were in contrast to the slow mobilization of the United States Army in the war. In 1900, the General Board of the United States Navy decided to give the Marine Corps primary responsibility for the seizure and defense of advanced naval bases. The Marine Corps formed an expeditionary battalion to be permanently based in the Caribbean, which subsequently practiced landings in 1902 in preparation for a war with Germany over their Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903, siege in Venezuela. Under Major Lejeune, in early 1903, it also undertook landing exercises with the Army in

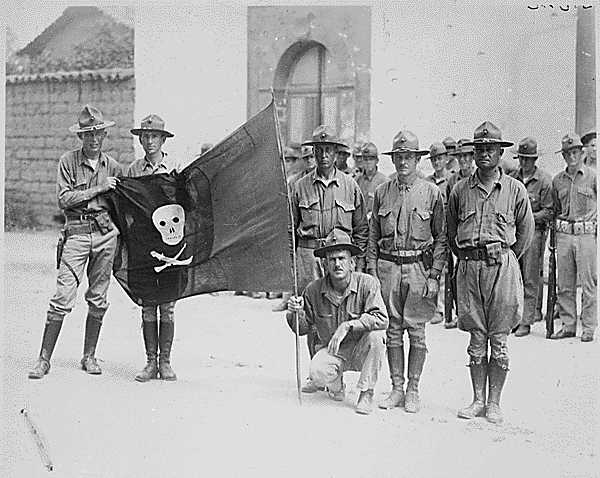

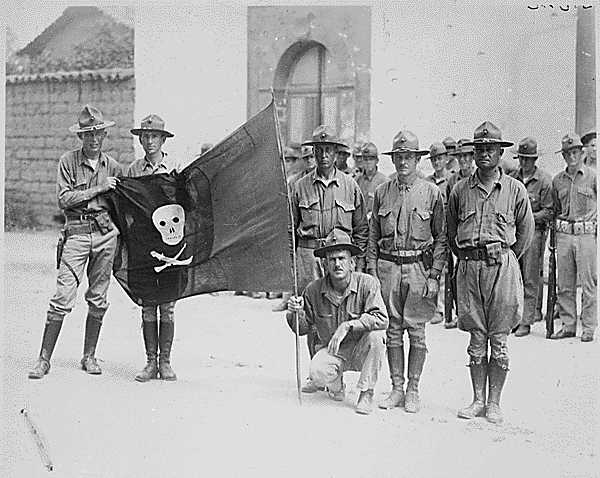

Between 1900 and 1916, the Marine Corps continued its record of participation in foreign expeditions, especially in the Caribbean and Central and

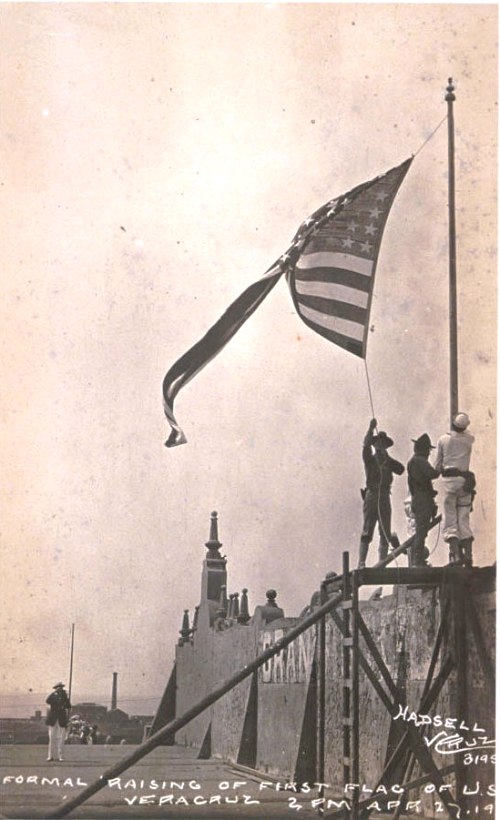

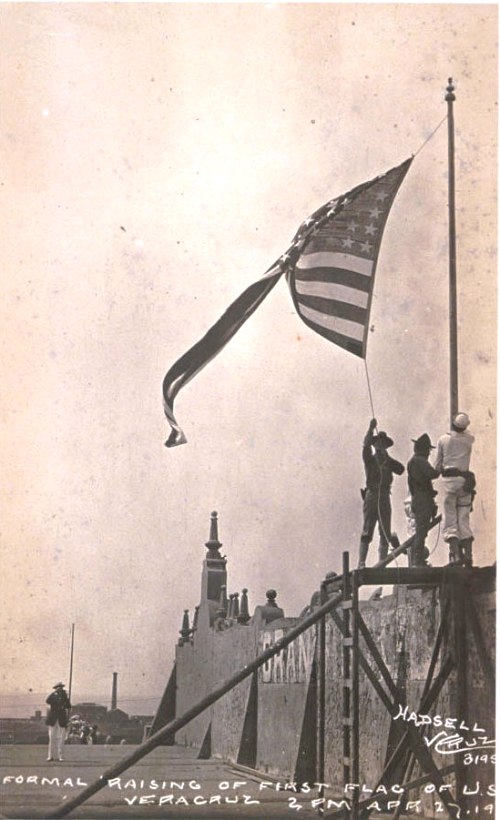

Between 1900 and 1916, the Marine Corps continued its record of participation in foreign expeditions, especially in the Caribbean and Central and  Marines also United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution, returned to Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. From 5 to 7 September 1903, Marines protected Americans evacuating the Yaqui River Valley. In response to the Tampico Affair and to intercept weapons being shipped to Victoriano Huerta in spite of an arms embargo, Marines were deployed to

Marines also United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution, returned to Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. From 5 to 7 September 1903, Marines protected Americans evacuating the Yaqui River Valley. In response to the Tampico Affair and to intercept weapons being shipped to Victoriano Huerta in spite of an arms embargo, Marines were deployed to

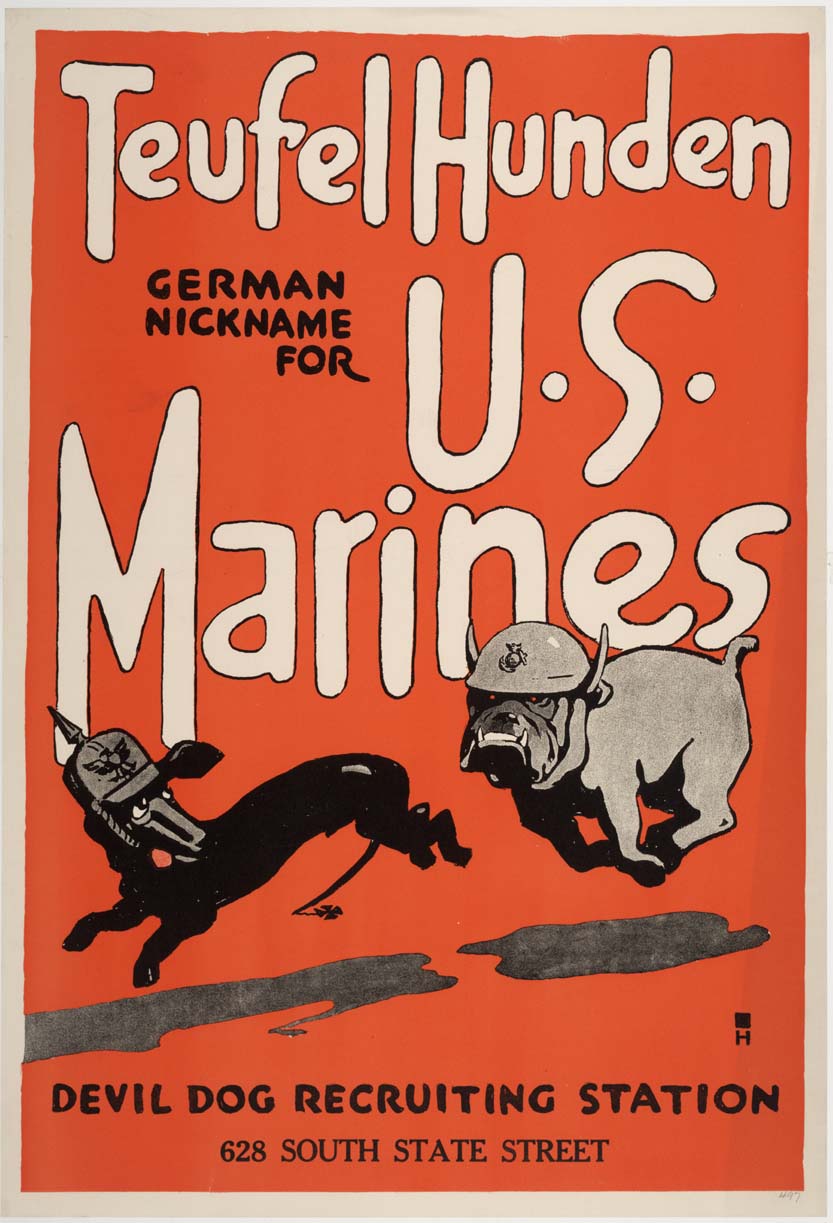

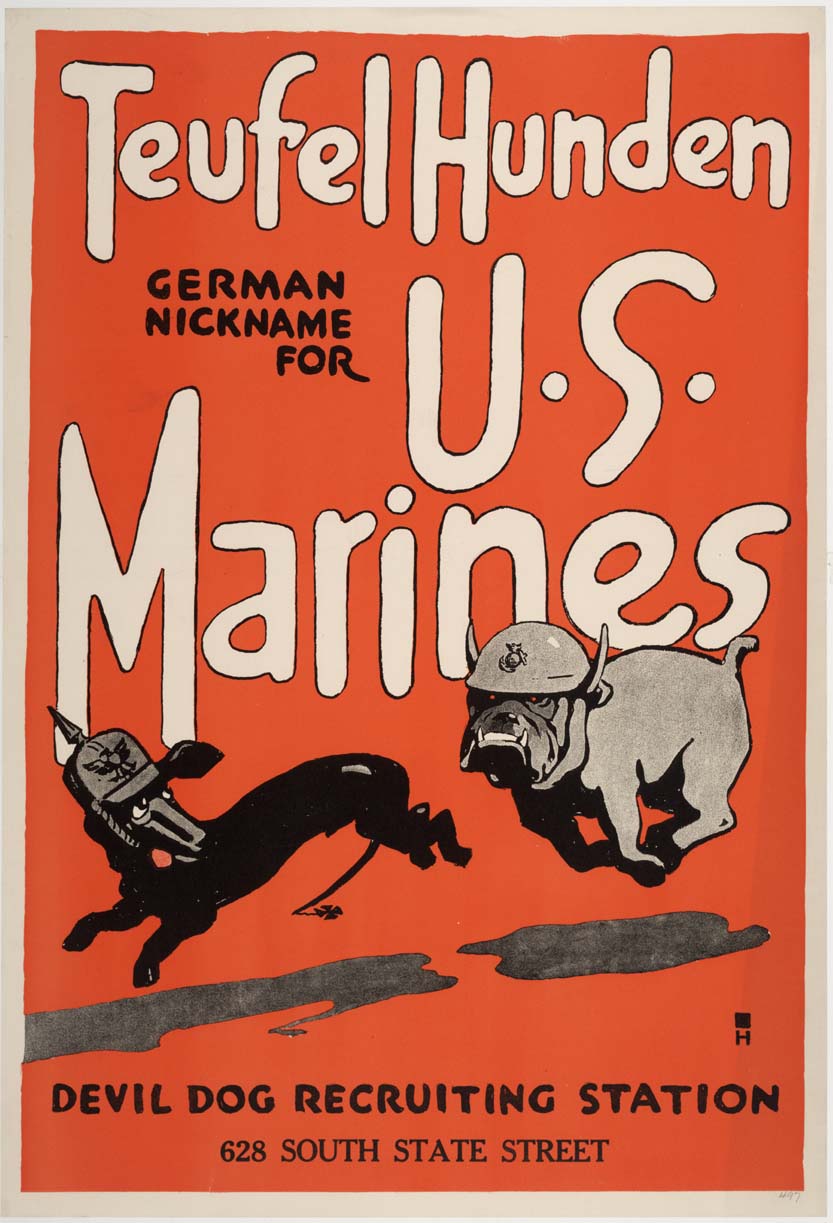

In 1917–1918, the Marine Corps had a deep pool of officers and

In 1917–1918, the Marine Corps had a deep pool of officers and  The French government renamed the forest to "Bois de la Brigade de Marine" ("Wood of the Marine Brigade"), and decorated both the 5th Marine Regiment, 5th and 6th Marine Regiment, 6th Regiments with the Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), Croix de Guerre three times each. This earned them the privilege to wear the fourragère, which Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Secretary of the Navy, authorized them to henceforth wear on the left shoulder of their dress and service uniforms. Marine aviation also saw exponential growth, as the ''First Aeronautic Company'' which deployed to the Azores to hunt U-boats in January 1918 and the ''First Marine Air Squadron'' which deployed to

The French government renamed the forest to "Bois de la Brigade de Marine" ("Wood of the Marine Brigade"), and decorated both the 5th Marine Regiment, 5th and 6th Marine Regiment, 6th Regiments with the Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), Croix de Guerre three times each. This earned them the privilege to wear the fourragère, which Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Secretary of the Navy, authorized them to henceforth wear on the left shoulder of their dress and service uniforms. Marine aviation also saw exponential growth, as the ''First Aeronautic Company'' which deployed to the Azores to hunt U-boats in January 1918 and the ''First Marine Air Squadron'' which deployed to  Near the end of the war in June 1918, Marines were landed at Vladivostok in Russia to protect American citizens at the consulate and other places from the fighting of the Russian Civil War. That August, Siberian intervention, the Allies would intervene on the side of the White movement, White Russians against the Bolsheviks to protect the Czechoslovak Legions and Allied materiel from capture. Marines would return on 16 February 1920, this time to Russky Island to protect communications infrastructure, until 19 November 1922.

Near the end of the war in June 1918, Marines were landed at Vladivostok in Russia to protect American citizens at the consulate and other places from the fighting of the Russian Civil War. That August, Siberian intervention, the Allies would intervene on the side of the White movement, White Russians against the Bolsheviks to protect the Czechoslovak Legions and Allied materiel from capture. Marines would return on 16 February 1920, this time to Russky Island to protect communications infrastructure, until 19 November 1922.

Opha May Johnson was the first woman to enlist in the Marines; she joined the United States Marine Corps Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve in 1918, officially becoming the first female Marine. From then until the end of World War I, 305 women enlisted in the Corps.

The Marine Corps had entered the war with 511 officers and 13,214 enlisted personnel and, by 11 November 1918, had reached a strength of 2,400 officers and 70,000 enlisted. The war cost 2,461 dead and 9,520 wounded Marines, while eight would earn the Medal of Honor. Most of the deaths came from the worldwide Spanish flu epidemic.

Opha May Johnson was the first woman to enlist in the Marines; she joined the United States Marine Corps Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve in 1918, officially becoming the first female Marine. From then until the end of World War I, 305 women enlisted in the Corps.

The Marine Corps had entered the war with 511 officers and 13,214 enlisted personnel and, by 11 November 1918, had reached a strength of 2,400 officers and 70,000 enlisted. The war cost 2,461 dead and 9,520 wounded Marines, while eight would earn the Medal of Honor. Most of the deaths came from the worldwide Spanish flu epidemic.

Between the world wars, the Marine Corps was headed by Major General John A. Lejeune, another popular commandant. The Marine Corps was searching for an expanded mission after World War I. It was used in France as a junior version of the army infantry, and Marines realized that was a dead end. In the early 20th century they had acquired the new mission of police control of Central American countries partly occupied by the US. That mission became another dead end when the nation adopted a "Good Neighbor Policy" toward Latin America, and renounced further invasions. The corps needed a new mission, one distinct from the army. It found one: it would be a fast-reacting, light infantry fighting force carried rapidly to far off locations by the navy. Its special role was amphibious landings on enemy-held islands, but it took years to figure out how to do that. The Mahanian notion of a decisive fleet battle required forward bases for the navy close to the enemy. After the Spanish–American War the Marines gained the mission of occupying and defending those forward bases, and they began a training program on Culebro Island, Puerto Rico. The emphasis at first was on defending the forward base against enemy attack.

As early as 1900 the Navy's General Board considered building advance bases for naval operations in the Pacific and the Caribbean. The Marine Corps was given a defensive mission in 1920. The conceptual breakthrough came in 1921 when Earl Hancock Ellis, Major "Pete" Ellis wrote "Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia" a secret 30,000-word manifesto that proved inspirational to Marine strategists and highly prophetic. To win a war in the Pacific, the Navy would have to fight its way through thousands of miles of ocean controlled by the Japanese—including the Marshall, Caroline, Marianas and Ryukus island groups. If the Navy could land Marines to seize selected islands, they could become forward bases. Ellis argued that with an enemy prepared to defend the beaches, success depended on high-speed movement of waves of assault craft, covered by heavy naval gunfire and attack from the air. He predicted the decision would take place on the beach itself, so the assault teams would need not just infantry but also machine gun units, light artillery, light tanks, and combat engineers to defeat beach obstacles and defenses. Assuming the enemy had its own artillery, the landing craft would have to be specially built to protect the landing force. With American naval control, the Japanese would be unable to land new forces on the islands under attack.

Not knowing which of the many islands would be the American target, the Japanese would have to disperse their strength by garrisoning many islands that would never be attacked. An island like Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands, would, Ellis estimated, require two regiments, or 4,000 Marines. (Indeed, in February 1944 the Marines seized Eniwetok with 4,000 men in three battalions.) Guided by Marine observer airplanes, and supplemented by Marine light bombers, warships would provide sea-going artillery firepower so that Marines would not need any heavy artillery (in contrast to the Army, which relied heavily on its artillery.) Shelling defended islands was a new mission for warships. The Ellis model was officially endorsed in 1927 by the Joint Board of the Army and Navy (a forerunner of the Joint Chiefs of Staff).

Between the world wars, the Marine Corps was headed by Major General John A. Lejeune, another popular commandant. The Marine Corps was searching for an expanded mission after World War I. It was used in France as a junior version of the army infantry, and Marines realized that was a dead end. In the early 20th century they had acquired the new mission of police control of Central American countries partly occupied by the US. That mission became another dead end when the nation adopted a "Good Neighbor Policy" toward Latin America, and renounced further invasions. The corps needed a new mission, one distinct from the army. It found one: it would be a fast-reacting, light infantry fighting force carried rapidly to far off locations by the navy. Its special role was amphibious landings on enemy-held islands, but it took years to figure out how to do that. The Mahanian notion of a decisive fleet battle required forward bases for the navy close to the enemy. After the Spanish–American War the Marines gained the mission of occupying and defending those forward bases, and they began a training program on Culebro Island, Puerto Rico. The emphasis at first was on defending the forward base against enemy attack.

As early as 1900 the Navy's General Board considered building advance bases for naval operations in the Pacific and the Caribbean. The Marine Corps was given a defensive mission in 1920. The conceptual breakthrough came in 1921 when Earl Hancock Ellis, Major "Pete" Ellis wrote "Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia" a secret 30,000-word manifesto that proved inspirational to Marine strategists and highly prophetic. To win a war in the Pacific, the Navy would have to fight its way through thousands of miles of ocean controlled by the Japanese—including the Marshall, Caroline, Marianas and Ryukus island groups. If the Navy could land Marines to seize selected islands, they could become forward bases. Ellis argued that with an enemy prepared to defend the beaches, success depended on high-speed movement of waves of assault craft, covered by heavy naval gunfire and attack from the air. He predicted the decision would take place on the beach itself, so the assault teams would need not just infantry but also machine gun units, light artillery, light tanks, and combat engineers to defeat beach obstacles and defenses. Assuming the enemy had its own artillery, the landing craft would have to be specially built to protect the landing force. With American naval control, the Japanese would be unable to land new forces on the islands under attack.

Not knowing which of the many islands would be the American target, the Japanese would have to disperse their strength by garrisoning many islands that would never be attacked. An island like Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands, would, Ellis estimated, require two regiments, or 4,000 Marines. (Indeed, in February 1944 the Marines seized Eniwetok with 4,000 men in three battalions.) Guided by Marine observer airplanes, and supplemented by Marine light bombers, warships would provide sea-going artillery firepower so that Marines would not need any heavy artillery (in contrast to the Army, which relied heavily on its artillery.) Shelling defended islands was a new mission for warships. The Ellis model was officially endorsed in 1927 by the Joint Board of the Army and Navy (a forerunner of the Joint Chiefs of Staff).

Actual implementation of the new mission took another decade because the Corps was preoccupied in Central America, the Navy was slow to start training in how to support the landings, and new kinds of ships had to be invented to hit the beaches without massive casualties. In 1941 British and American ship architects invented new classes of "landing ships" to solve the problem. In World War II, the Navy contracted to build 1,150 LSTs, of which 332 would be cancelled or diverted to allies or converted for use as Auxiliary ship, auxiliaries. They were large (2400 tons) and slow (10 knots); officially known as Landing Ship, Tank, the passengers called them "Large Stationary Targets." Lightly armored, they could steam cross the ocean with a full load on their own power, carrying infantry, tanks and supplies directly onto the beaches. Another type of ship, the LSD or Dock landing ship, Landing Ship, Dock, could carry three dozen Landing Craft Mechanized, Landing Craft Mechanized (LCU) with Marines, vehicles, and materiel in a flooding well deck for launching; 21 of these ships were built for U.S. service. Together with 2,000 other landing craft and ships, the LSDs and LSTs gave the Marines (and Army soldiers) a protected, quick way to make combat landings, beginning in summer 1943.The naval historian Norman Friedman would write in ''U.S. Amphibious Ships and Craft: An Illustrated Design History'' (Naval Institute Press, 2002, pg 130) that "Unlike the LST, the LSD was well adapted to the style of amphibious warfare the United States intended to execute in the Central Pacific." Both types were originally designed with European landings in mind, hence the British involvement.

In 1933, a "Fleet Marine Force" was established with the primary mission of amphibious landings. The Force was a brigade with attached Marine aviation units that were trained in observation and ground support. By paying special attention to communications between ground and air, and between shore and sea, they developed an integrated three-dimensional assault force. By 1940, having adding enough men, the appropriate equipment, and a rigorous training program, the Marine Corps had worked out, in theory, its doctrine of amphibious assaults. Under the combat leadership of Holland "Howlin Mad" Smith, the general most responsible for training, the Marines were ready to hit the beaches.

The Corps acquired amphibious equipment such as the LCVP (United States), Higgins boat (LCVP), the Landing Vehicle Tracked, Amtrak (LTV), and the DUKW, which would prove of great use in the upcoming conflict. The various Fleet Landing Exercises were a test and demonstration of the Corps' growing amphibious capabilities.

Marine aviation also saw significant growth in assets; on 7 December 1941, Marine aviation consisted of 13 flying squadrons and 230 aircraft. The oldest squadron in the Corps, known today as VMFA-232, was commissioned on 1 September 1925, as VF-3M.

Actual implementation of the new mission took another decade because the Corps was preoccupied in Central America, the Navy was slow to start training in how to support the landings, and new kinds of ships had to be invented to hit the beaches without massive casualties. In 1941 British and American ship architects invented new classes of "landing ships" to solve the problem. In World War II, the Navy contracted to build 1,150 LSTs, of which 332 would be cancelled or diverted to allies or converted for use as Auxiliary ship, auxiliaries. They were large (2400 tons) and slow (10 knots); officially known as Landing Ship, Tank, the passengers called them "Large Stationary Targets." Lightly armored, they could steam cross the ocean with a full load on their own power, carrying infantry, tanks and supplies directly onto the beaches. Another type of ship, the LSD or Dock landing ship, Landing Ship, Dock, could carry three dozen Landing Craft Mechanized, Landing Craft Mechanized (LCU) with Marines, vehicles, and materiel in a flooding well deck for launching; 21 of these ships were built for U.S. service. Together with 2,000 other landing craft and ships, the LSDs and LSTs gave the Marines (and Army soldiers) a protected, quick way to make combat landings, beginning in summer 1943.The naval historian Norman Friedman would write in ''U.S. Amphibious Ships and Craft: An Illustrated Design History'' (Naval Institute Press, 2002, pg 130) that "Unlike the LST, the LSD was well adapted to the style of amphibious warfare the United States intended to execute in the Central Pacific." Both types were originally designed with European landings in mind, hence the British involvement.

In 1933, a "Fleet Marine Force" was established with the primary mission of amphibious landings. The Force was a brigade with attached Marine aviation units that were trained in observation and ground support. By paying special attention to communications between ground and air, and between shore and sea, they developed an integrated three-dimensional assault force. By 1940, having adding enough men, the appropriate equipment, and a rigorous training program, the Marine Corps had worked out, in theory, its doctrine of amphibious assaults. Under the combat leadership of Holland "Howlin Mad" Smith, the general most responsible for training, the Marines were ready to hit the beaches.

The Corps acquired amphibious equipment such as the LCVP (United States), Higgins boat (LCVP), the Landing Vehicle Tracked, Amtrak (LTV), and the DUKW, which would prove of great use in the upcoming conflict. The various Fleet Landing Exercises were a test and demonstration of the Corps' growing amphibious capabilities.

Marine aviation also saw significant growth in assets; on 7 December 1941, Marine aviation consisted of 13 flying squadrons and 230 aircraft. The oldest squadron in the Corps, known today as VMFA-232, was commissioned on 1 September 1925, as VF-3M.

In

In  As the Marine Corps grew to its maximum size, Marine aviation also peaked at 5 Wing (military unit), air wings, 31 Group (military unit), aircraft groups and 145 flying Squadron (aviation), squadrons. The Battle of Guadalcanal would teach several lessons, such as the debilitating effects of not having Air supremacy, air superiority, the vulnerability of unescorted targets (such as transport shipping), and the vital importance of quickly acquiring expeditionary airfields during amphibious operations. After being dissatisfied with Navy air support at the Battle of Tarawa, General Holland Smith recommended that Marines should do the job, put into effect at New Georgia campaign, New Georgia. The Bougainville campaign, Bougainville and Philippines campaign (1944–45), 2nd Philippines campaigns saw the establishment of Tactical Air Control Party, air liaison parties to coordinate air support with the Marines fighting on the ground, and the Battle of Okinawa brought most of it together with the establishment of aviation command and control in the form of Direct Air Support Center, Landing Force Air Support Control Units

Though the vast majority of Marines served in the Pacific Theater, a number of Marines did play a role in the European theatre of World War II, European Theater, North African campaign, North Africa, and Middle East. The largest Marine unit in Europe was the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, 1st Provisional Marine Brigade#Iceland, which served in Iceland from July 1941 through March 1942 before transfer to the Pacific. Most others served aboard warships and as guards for naval bases, especially in the British Isles; though some volunteered for duty with the Office of Strategic Services. Numerous observers were dispatched to learn tactics from other allied nations, such as Roy Geiger aboard . Interservice rivalry may have played a role in this; for example, when briefed of a plan for Project Danny, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, George Marshall stood and walked out, stating "That's the end of this briefing. As long as I'm in charge, there'll never be a Marine in Europe."

By the war's end, the Corps had grown to include six divisions, five air wings and supporting troops totaling about 485,000 Marines. 19,733 Marines were killed and 68,207 wounded during WWII and 82 received the Medal of Honor. Marine Aviators were credited with shooting down 2,355 Japanese aircraft while losing 573 of their own in combat, as well as 120 earning Flying ace, ace.

As the Marine Corps grew to its maximum size, Marine aviation also peaked at 5 Wing (military unit), air wings, 31 Group (military unit), aircraft groups and 145 flying Squadron (aviation), squadrons. The Battle of Guadalcanal would teach several lessons, such as the debilitating effects of not having Air supremacy, air superiority, the vulnerability of unescorted targets (such as transport shipping), and the vital importance of quickly acquiring expeditionary airfields during amphibious operations. After being dissatisfied with Navy air support at the Battle of Tarawa, General Holland Smith recommended that Marines should do the job, put into effect at New Georgia campaign, New Georgia. The Bougainville campaign, Bougainville and Philippines campaign (1944–45), 2nd Philippines campaigns saw the establishment of Tactical Air Control Party, air liaison parties to coordinate air support with the Marines fighting on the ground, and the Battle of Okinawa brought most of it together with the establishment of aviation command and control in the form of Direct Air Support Center, Landing Force Air Support Control Units

Though the vast majority of Marines served in the Pacific Theater, a number of Marines did play a role in the European theatre of World War II, European Theater, North African campaign, North Africa, and Middle East. The largest Marine unit in Europe was the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, 1st Provisional Marine Brigade#Iceland, which served in Iceland from July 1941 through March 1942 before transfer to the Pacific. Most others served aboard warships and as guards for naval bases, especially in the British Isles; though some volunteered for duty with the Office of Strategic Services. Numerous observers were dispatched to learn tactics from other allied nations, such as Roy Geiger aboard . Interservice rivalry may have played a role in this; for example, when briefed of a plan for Project Danny, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, George Marshall stood and walked out, stating "That's the end of this briefing. As long as I'm in charge, there'll never be a Marine in Europe."

By the war's end, the Corps had grown to include six divisions, five air wings and supporting troops totaling about 485,000 Marines. 19,733 Marines were killed and 68,207 wounded during WWII and 82 received the Medal of Honor. Marine Aviators were credited with shooting down 2,355 Japanese aircraft while losing 573 of their own in combat, as well as 120 earning Flying ace, ace.

The

The

The Marines also played an important role in the

The Marines also played an important role in the

Returning from South Vietnam, the Marine Corps hit one of the lowest points in its history with high rates of courts-martial, non-judicial punishments, Desertion, unauthorized absences, and outright desertions. The re-making of the Marine Corps began in the late 1970s when policies for Military discharge, discharging inadequate Marines were relaxed leading to the removal of the worst performing ones. Once the quality of new recruits started to improve, the Marines began reforming their NCO corps, an absolutely vital element in the functioning of the Marine Corps. After Vietnam, the Marine Corps resumed its expeditionary role.

On 4 November 1979, Islamism, Islamist students supporting the so-called Iranian Revolution stormed the Embassy of the United States, Tehran, Embassy of the United States in Tehran and took 53 hostages, including the Marine Security Guards. Marine helicopter pilots took part in Operation Eagle Claw, the disastrous rescue attempt on 24 April 1980. An unexpected sandstorm grounded several Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion, RH-53 helicopters, as well as scattering the rest, and ultimately killing several when one struck an Lockheed EC-130, EC-130 Hercules staged to refuel them. The mission was aborted, and the Algiers Accords negotiated the release of the hostages on 20 January 1981. The mission demonstrated the need for an aircraft that could V/STOL, take off and land vertically, but had greater speed than a helicopter, realized decades later in the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, V-22 Osprey.

Returning from South Vietnam, the Marine Corps hit one of the lowest points in its history with high rates of courts-martial, non-judicial punishments, Desertion, unauthorized absences, and outright desertions. The re-making of the Marine Corps began in the late 1970s when policies for Military discharge, discharging inadequate Marines were relaxed leading to the removal of the worst performing ones. Once the quality of new recruits started to improve, the Marines began reforming their NCO corps, an absolutely vital element in the functioning of the Marine Corps. After Vietnam, the Marine Corps resumed its expeditionary role.

On 4 November 1979, Islamism, Islamist students supporting the so-called Iranian Revolution stormed the Embassy of the United States, Tehran, Embassy of the United States in Tehran and took 53 hostages, including the Marine Security Guards. Marine helicopter pilots took part in Operation Eagle Claw, the disastrous rescue attempt on 24 April 1980. An unexpected sandstorm grounded several Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion, RH-53 helicopters, as well as scattering the rest, and ultimately killing several when one struck an Lockheed EC-130, EC-130 Hercules staged to refuel them. The mission was aborted, and the Algiers Accords negotiated the release of the hostages on 20 January 1981. The mission demonstrated the need for an aircraft that could V/STOL, take off and land vertically, but had greater speed than a helicopter, realized decades later in the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, V-22 Osprey.

Marines returned to Beirut during the

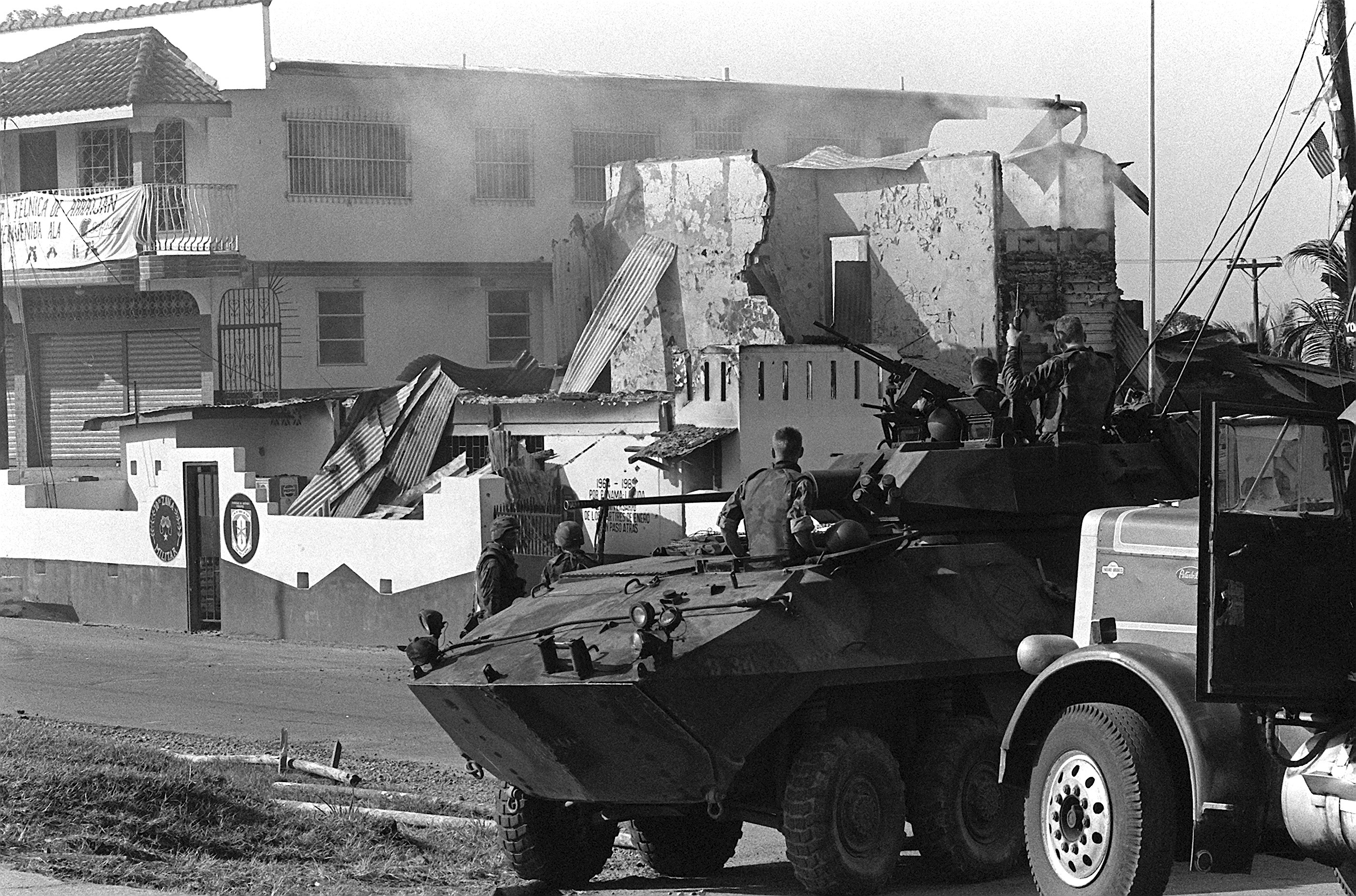

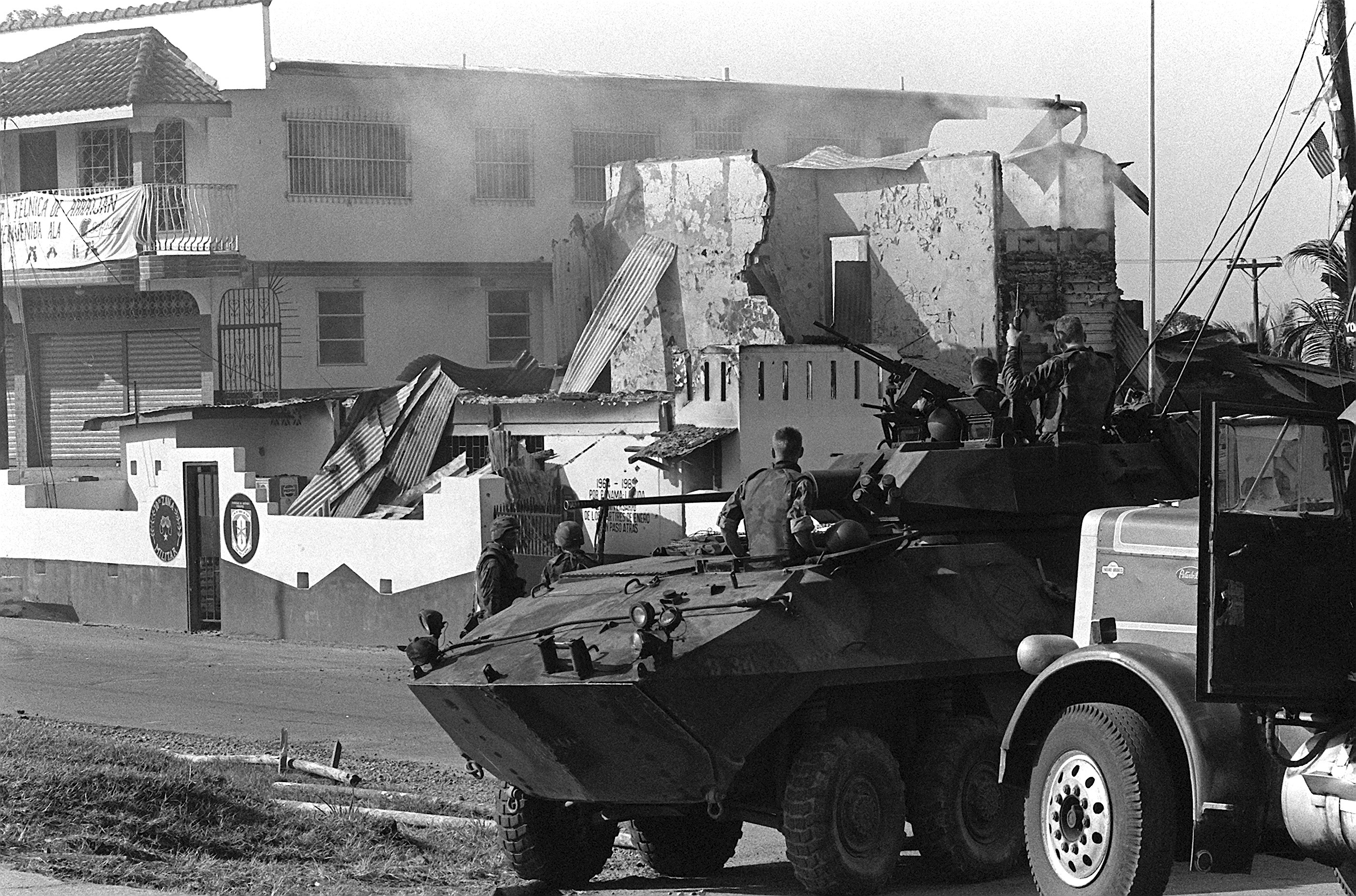

Marines returned to Beirut during the  Marines recovered from this low point and began a series of successes. The United States invasion of Grenada, Invasion of Grenada, known as "Operation Urgent Fury", began on 25 October 1983 in response to a coup by Bernard Coard and possible "Soviet-Cuban militarization" on the island. The 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit quickly took the northern sectors, and were withdrawn by 15 December. Interservice rivalry and cooperation issues shown during the invasion resulted in the Goldwater–Nichols Act of 1986 altering the Command hierarchy, chain of command in the United States military. When Operation Classic Resolve began on 2 December 1989 in the Philippines (in retaliation for the 1989 Philippine coup d'état attempt, coup attempt), a company of Marines was dispatched from U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay, Naval Base Subic Bay to protect the Embassy of the United States, Manila, Embassy of the United States in Manila. The United States invasion of Panama, Invasion of Panama, known as "Operation Just Cause" began on 20 December of the same year, and deposed the military dictator Manuel Noriega.

Marines recovered from this low point and began a series of successes. The United States invasion of Grenada, Invasion of Grenada, known as "Operation Urgent Fury", began on 25 October 1983 in response to a coup by Bernard Coard and possible "Soviet-Cuban militarization" on the island. The 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit quickly took the northern sectors, and were withdrawn by 15 December. Interservice rivalry and cooperation issues shown during the invasion resulted in the Goldwater–Nichols Act of 1986 altering the Command hierarchy, chain of command in the United States military. When Operation Classic Resolve began on 2 December 1989 in the Philippines (in retaliation for the 1989 Philippine coup d'état attempt, coup attempt), a company of Marines was dispatched from U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay, Naval Base Subic Bay to protect the Embassy of the United States, Manila, Embassy of the United States in Manila. The United States invasion of Panama, Invasion of Panama, known as "Operation Just Cause" began on 20 December of the same year, and deposed the military dictator Manuel Noriega.

Marines played a modest role in the Bosnian War and NATO intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina, NATO intervention. Operation Deny Flight began on 12 April 1993, to enforce the United Nations no-fly zone in Bosnia and Herzegovina and provide air support to the United Nations Protection Force. The McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, F/A-18D Hornet was proven to be a "highly resourceful multirole platform", in addition to showcasing the importance of precision-guided munitions. In 1995, the mission was expanded to include a Operation Deliberate Force, bombing campaign called "Operation Deliberate Force". On 2 June 1995, United States Air Force, Air Force Captain Scott O'Grady's General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, F-16 was shot down by a Army of Republika Srpska, Bosnian Serb Army surface-to-air missile in the Scott O'Grady, Mrkonjić Grad incident. Marines from the 24th MEU, based on the , rescued him from western Bosnia on 8 June. Marines would support the Implementation Force, IFOR, Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina, SFOR, and Kosovo Force, KFOR until 1999. On 3 February 1998, an Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowler, EA-6B Prowler from VMAQ-2, deployed to Aviano Air Base to support the peacekeeping effort, Cavalese cable car disaster (1998), hit an aerial tram cable and killed 20 European passengers.

Marines played a modest role in the Bosnian War and NATO intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina, NATO intervention. Operation Deny Flight began on 12 April 1993, to enforce the United Nations no-fly zone in Bosnia and Herzegovina and provide air support to the United Nations Protection Force. The McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, F/A-18D Hornet was proven to be a "highly resourceful multirole platform", in addition to showcasing the importance of precision-guided munitions. In 1995, the mission was expanded to include a Operation Deliberate Force, bombing campaign called "Operation Deliberate Force". On 2 June 1995, United States Air Force, Air Force Captain Scott O'Grady's General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, F-16 was shot down by a Army of Republika Srpska, Bosnian Serb Army surface-to-air missile in the Scott O'Grady, Mrkonjić Grad incident. Marines from the 24th MEU, based on the , rescued him from western Bosnia on 8 June. Marines would support the Implementation Force, IFOR, Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina, SFOR, and Kosovo Force, KFOR until 1999. On 3 February 1998, an Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowler, EA-6B Prowler from VMAQ-2, deployed to Aviano Air Base to support the peacekeeping effort, Cavalese cable car disaster (1998), hit an aerial tram cable and killed 20 European passengers.

In the summer of 1990, the 22nd and 26th Marine Expeditionary Units conducted Operation Sharp Edge, a noncombatant evacuation in the west Liberian city of Monrovia. Liberia First Liberian Civil War, suffered from civil war at the time, and citizens of the United States and other countries could not leave via conventional means. With only one reconnaissance team having come under fire with no casualties incurred on either side, the Marines evacuated several hundred civilians within hours to Navy vessels waiting offshore. On 8 April 1996, Marines returned for Operation Assured Response, helping in the evacuation of 2,444 foreign and United States citizens from Liberia. On 23 May 1996, President Bill Clinton diverted Marines from Joint Task Force Assured Response to Bangui, Central African Republic until 22 June, where they provided security to the American Embassy and evacuated 448 people. Due to increased threats against Americans as part of the fallout from the 1997 Albanian civil unrest, Lottery Uprising in Albania, 200 Marines and 10 United States Navy SEALs, Navy SEALs were deployed on 16 August 1998 to the American embassy there. As Indonesian occupation of East Timor, Indonesian occupation of East Timor ended in the fall of 1999, President Clinton authorized the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, based on the , to deploy there until the International Force East Timor, International Force for East Timor could arrive in October.

Marines participated in combat operations in Somalia (1992–1995) during Operations Unified Task Force, Restore Hope, Restore Hope II, and Operation United Shield, United Shield. While Operation Restore Hope was designated as a humanitarian relief effort, Marine ground forces frequently engaged Somali militiamen in combat. Elements of Battalion Landing Team 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, 2nd Battalion 9th Marines with 15th MEU were among the first troops of the United Nations effort to land in Somalia in December 1992, while Marines of Battalion Landing Team 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, 3rd Battalion 1st Marines participated in the final withdrawal of United Nations troops from Somalia in 1995.

In the summer of 1990, the 22nd and 26th Marine Expeditionary Units conducted Operation Sharp Edge, a noncombatant evacuation in the west Liberian city of Monrovia. Liberia First Liberian Civil War, suffered from civil war at the time, and citizens of the United States and other countries could not leave via conventional means. With only one reconnaissance team having come under fire with no casualties incurred on either side, the Marines evacuated several hundred civilians within hours to Navy vessels waiting offshore. On 8 April 1996, Marines returned for Operation Assured Response, helping in the evacuation of 2,444 foreign and United States citizens from Liberia. On 23 May 1996, President Bill Clinton diverted Marines from Joint Task Force Assured Response to Bangui, Central African Republic until 22 June, where they provided security to the American Embassy and evacuated 448 people. Due to increased threats against Americans as part of the fallout from the 1997 Albanian civil unrest, Lottery Uprising in Albania, 200 Marines and 10 United States Navy SEALs, Navy SEALs were deployed on 16 August 1998 to the American embassy there. As Indonesian occupation of East Timor, Indonesian occupation of East Timor ended in the fall of 1999, President Clinton authorized the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, based on the , to deploy there until the International Force East Timor, International Force for East Timor could arrive in October.

Marines participated in combat operations in Somalia (1992–1995) during Operations Unified Task Force, Restore Hope, Restore Hope II, and Operation United Shield, United Shield. While Operation Restore Hope was designated as a humanitarian relief effort, Marine ground forces frequently engaged Somali militiamen in combat. Elements of Battalion Landing Team 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, 2nd Battalion 9th Marines with 15th MEU were among the first troops of the United Nations effort to land in Somalia in December 1992, while Marines of Battalion Landing Team 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, 3rd Battalion 1st Marines participated in the final withdrawal of United Nations troops from Somalia in 1995.

Following the September 11 attacks of 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush announced the War on terror, War on Terrorism. The stated objective of the Global War on Terror is "the defeat of Al-Qaeda, other terrorism, terrorist groups and any nation that supports or harbors terrorists". Since then, the Marine Corps, alongside other military and federal agencies, has engaged in global operations around the world in support of that mission.

In 2002, Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa was stood up at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti, to provide regional security. Despite transferring overall command to the Navy in 2006, the Marines continued to Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa, operate in the Horn of Africa into 2010.

In the summer of 2006, Marines from the 24th MEU evacuated Americans from Lebanon and Israel in light of the fighting of the 2006 Lebanon War. The 22nd and 24th MEUs returned to Haiti after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, 2010 earthquake in January as part of Operation Unified Response.

Following the September 11 attacks of 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush announced the War on terror, War on Terrorism. The stated objective of the Global War on Terror is "the defeat of Al-Qaeda, other terrorism, terrorist groups and any nation that supports or harbors terrorists". Since then, the Marine Corps, alongside other military and federal agencies, has engaged in global operations around the world in support of that mission.

In 2002, Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa was stood up at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti, to provide regional security. Despite transferring overall command to the Navy in 2006, the Marines continued to Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa, operate in the Horn of Africa into 2010.

In the summer of 2006, Marines from the 24th MEU evacuated Americans from Lebanon and Israel in light of the fighting of the 2006 Lebanon War. The 22nd and 24th MEUs returned to Haiti after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, 2010 earthquake in January as part of Operation Unified Response.

online

a major scholarly history * * * Venable, Heather P. '' How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874–1918'' (Naval Institure Press, 2019). ;World War I * * * ; Amphibious warfare * Isely Jeter A., Philip A. Crowl. ''The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War Its Theory and Its Practice in the Pacific'' (1951) * Moore, Richard S. "Ideas and Direction: Building Amphibious Doctrine," ''Marine Corps Gazette'' (1982) 66#11 pp 49–58. * Reber, John J. "Pete Ellis: Amphibious Warfare Prophet," ''U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings'' (1977) 103#11 pp 53–64. * Venzon, Anne Cipriano. ''From Whaleboats to Amphibious Warfare: Lt. Gen. "Howling Mad" Smith and the U.S. Marine Corps'' (Praeger, 2003) ;World War II * Forty, George. ''US Marine Corps Handbook 1941–45'' (The History Press, 2013). * * * * * * * * ;Vietnam and recent * Camp, Dick. ''Assault from the Sky: US Marine Corps Helicopter Operations in Vietnam'' (Casemate, 2013). * Gilbert, Ed. ''The US Marine Corps in the Vietnam War: III Marine Amphibious Force 1965–75'' (Osprey Publishing, 2013). * Holmes-Eber, Paula. ''Culture in conflict: Irregular warfare, culture policy, and the Marine Corps'' (Stanford University Press, 2014). * * Southard, John. ''Defend and Befriend: The US Marine Corps and Combined Action Platoons in Vietnam'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2014). * Pettegrew, John. ''Light It Up: The Marine Eye for Battle in the War for Iraq'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015). xvi, 215 pp. * Shultz Jr., Richard H. ''The Marines Take Anbar: The Four Year Fight Against al Qaeda'' (2013)

Marine Corps University Research Library

Navy & Marine Living History Association

{{authority control History of the United States Marine Corps, History of the United States Armed Forces by service branch Military units and formations established in 1775

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

of the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionar ...

(USMC) begins with the founding of the Continental Marines

The Continental Marines were the Amphibious warfare, amphibious infantry of the Thirteen Colonies, American Colonies (and later the United States) during the American Revolutionary War. The Corps was formed by the Continental Congress on Novem ...

on 10 November 1775 to conduct ship-to-ship fighting, provide shipboard security and discipline enforcement, and assist in landing forces. Its mission evolved with changing military doctrine and foreign policy of the United States. Owing to the availability of Marine forces at sea, the United States Marine Corps has served in nearly every conflict in United States history. It attained prominence when its theories and practice of amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conduc ...

proved prescient, and ultimately formed a cornerstone of U.S. strategy in the Pacific Theater of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. By the early 20th century, the Marine Corps would become one of the dominant theorists and practitioners of amphibious warfare. Its ability to rapidly respond on short notice to expeditionary crises has made and continues to make it an important tool for U.S. foreign policy

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

.

In February 1776, the Continental Marines embarked on their maiden expedition. The Continental Marines were disbanded at the end of the war, along with the Continental Navy. In preparation for the Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

with France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

created the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

and the Marine Corps. The Marines' most famous action of this period occurred in the First Barbary War

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the 1801–1815 Barbary Wars, in which the United States fought against Ottoman Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war ...

(1801–1805) against the Barbary pirates

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

. In the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

(1846–1848), the Marines made their famed assault on Chapultepec Palace, which overlooked Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

, their first major expeditionary venture. In the 1850s, the Marines would see service in Panama, and in Asia. During the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865) the Marine Corps played only a minor role after their participation in the Union defeat at the first battle of First Bull Run/Manassas. Their most important task was blockade duty and other ship-board battles, but they were mobilized for a handful of operations as the war progressed. The remainder of the 19th century would be a period of declining strength and introspection about the mission of the Marine Corps. Under Commandant Jacob Zeilin

Jacob Zeilin (July 16, 1806 – November 18, 1880) was an American military officer who served as the seventh Commandant of the United States Marine Corps from 1864 to 1876. He served in the United States Marine Corps for over 45 years including ...

's term (1864–1876), many Marine customs and traditions took shape. During the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

(1898), Marines would lead U.S. forces ashore in the Philippines, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, demonstrating their readiness for deployment. Between 1900 and 1916, the Marine Corps continued its record of participation in foreign expeditions, especially in the Caribbean and Central and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, which included Panama, Cuba, Veracruz, Haiti, Santo Domingo, and Nicaragua.

In World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, battle-tested, veteran Marines served a central role in the United States' entry into the conflict. Between the world wars, the Marine Corps was headed by Major General John A. Lejeune, another popular commandant. In World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Marines played a central role, under Admiral Nimitz, in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, participating in nearly every significant battle. The Corps also saw its peak growth as it expanded from two brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

s to two corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

with six divisions, and five air wings with 132 squadrons. During the Battle of Iwo Jima

The was a major battle in which the United States Marine Corps (USMC) and United States Navy (USN) landed on and eventually captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) during World War II. The American invasion, desi ...

, photographer Joe Rosenthal took the famous photo '' Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima'' of five Marines and one naval corpsman raising a U.S. flag on Mount Suribachi. The Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

(1950–1953) saw the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade holding the line at the Battle of Pusan Perimeter

The Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, known in Korean as the Battle of the Naktong River Defense Line (), was a large-scale battle between United Nations Command (UN) and North Korean forces lasting from August 4 to September 18, 1950. It was one ...

, where Marine helicopters (VMO-6

Marine Observation Squadron 6 (VMO-6) was an observation squadron of the United States Marine Corps which saw extensive action during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II and the Korean War, Korean and Vietnam Wars. The squadron was the first ...

flying the HO3S1 helicopter) made their combat debut. The Marines also played an important role in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

at battles such as Da Nang

Da Nang or DanangSee also Danang Dragons (, ) is the fifth-largest city in Vietnam by municipal population. It lies on the coast of the Western Pacific Ocean of Vietnam at the mouth of the Hàn River, and is one of Vietnam's most important p ...

, Huế

Huế (formerly Thừa Thiên Huế province) is the southernmost coastal Municipalities of Vietnam, city in the North Central Coast region, the Central Vietnam, Central of Vietnam, approximately in the center of the country. It borders Quảng ...

, and Khe Sanh. The Marines operated in the northern I Corps regions of South Vietnam and fought both a constant guerilla war against the Viet Cong

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, and ...

and an off and on conventional war against North Vietnamese Army

The People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), officially the Vietnam People's Army (VPA; , , ), also recognized as the Vietnamese Army (), the People's Army () or colloquially the Troops ( ), is the national Military, military force of the Vietnam, S ...

regulars. Marines went to Beirut during the 1982 Lebanon War

The 1982 Lebanon War, also called the Second Israeli invasion of Lebanon, began on 6 June 1982, when Israel invaded southern Lebanon. The invasion followed a series of attacks and counter-attacks between the Palestine Liberation Organization ...

on 24 August. On 23 October 1983, the Marine barracks in Beirut was bombed, causing the highest peacetime losses to the Corps in its history. Marines were also responsible for liberating Kuwait during the Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

(1990–1991), as the Army made an attack to the west directly into Iraq. The I Marine Expeditionary Force

The I Marine Expeditionary Force ("I" pronounced "One") is a Marine Air Ground Task Force (MAGTF) of the United States Marine Corps primarily composed of the 1st Marine Division, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, and 1st Marine Logistics Group. It i ...

had a strength of 92,990, making Operation Desert Storm the largest Marine Corps operation in history.

Background

American Revolution

As the newly appointed commander of the Continental Army, George Washington was desperate for firearms, powder, and provisions; he opted to supply his own force frommatériel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers eith ...

from captured British military transports. To further expand his fleet, he also resorted to the maritime regiment of the Massachusetts militia

This is a list of militia units of the Colony and later Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

* Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts (1638)

* Cogswell's Regiment of Militia (April 19, 1775)

* Woodbridge's Regiment of Militia (April ...

, the 14th Continental Regiment (also known as the "Marblehead Regiment") to help muster in ranks. This unique regiment subsequently folded into Washington's army in January 1776. The Marblehead Regiment was entirely composed of New England mariners, providing little difficulty in administering crews for Washington's navy.

His decision to create his fleet came without difficulties in recruiting new rebel naval forces either, for the siege of Boston stirred the war along the entire coast of New England and into the strategic Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

area on the New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

border. The Royal Navy concentrated its vessels in the New England open waters, while its smaller warships raided the coastal towns and destroyed rebel military stores for supplies and provisions; and to punish the colonials for their rebellion—in accordance to the Proclamation of Rebellion

The Proclamation of Rebellion, officially titled A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, was the response of George III of Great Britain, George III to the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill at the outset of the American Revolution ...

that was chartered by King George. In response, several small vessels were commissioned by the governments of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

by the summer of 1775, authorizing the privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

ing against British government ships. In August 1775, Washington's makeshift naval fleet continued the interdiction of Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

; being a huge success, by the end of the year he was in command of four warships: , , , and .

Meanwhile, the New England militia forces of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

(the Green Mountain Boys

The Green Mountain Boys were a militia organization established in 1770 in the territory between the British provinces of New York and New Hampshire, known as the New Hampshire Grants and later in 1777 as the Vermont Republic (which later be ...

), under the command of Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

, seized the strategic post of Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain in northern New York. It was constructed between October 1755 and 1757 by French-Canadian ...

and temporarily eliminated British control of Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

–using a small flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' ( fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same cla ...

of shallow-draft vessels armed with light artillery. Early as May 1775, the sloop ' ushered eighteen men, presumably the Massachusetts militiamen, as marines on the payroll. Later in May, the Connecticut Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety () was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. Supplementing the Committee of General D ...

consigned £500 to Arnold, the shipment of payment was "escorted with Eight marines..well spirited and equipped,". although they were actually seamen. They are often referred to as the "Original Eight".

By August 1775, the Rhode Island Assembly, along with other colonial committees of safety, requested Second Continental Congress for naval assistance from Royal Navy raiders but it was appealed. Although Congress was aware of Britain's naval strength and its own financial limitations, it addressed itself reluctantly to the problem of creating a formidable continental navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United Colonies and United States from 1775 to 1785. It was founded on October 13, 1775 by the Continental Congress to fight against British forces and their allies as part of the American Revolutionary ...

. They were hesitant to the requests, only positing that they were only able to form a naval force from Washington's and Arnold's fleets; the colonies were left to fend for themselves. As a result, Rhode Island established their own state navy.

The colonial marines of Washington's naval fleet, Benedict Arnold's Lake Champlain flotilla, and privateers, made no distinction of their duties as their activities were no different from English customs: marines were basically soldiers detailed for naval service whose primary duties were to fight aboard but not sail their ships. Washington's navy expeditions throughout the remaining months of 1775 suggested that his ship crews of mariner-militiamen were not divided distinctly between sailors and marines; the Marblehead Regiment performed a plethora of duties aboard the warships. However, the Pennsylvania Committee of Public Safety made a dividing line between the sailors and marines when it decided to form a state navy to protect the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

and its littoral areas.

Early October, Congress members, such as John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, and colonial governments pushed Congress in creating a navy, however small. To examine the possible establishment of a national navy, the Naval Committee was appointed on 5 October (predecessor to the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

and Senate Committees on Naval Affairs). On 13 October 1775, Congress authorized its Naval Committee to form a squadron of four converted Philadelphia merchantmen, with the addition of two smaller vessels. Despite a shortage in funding, the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United Colonies and United States from 1775 to 1785. It was founded on October 13, 1775 by the Continental Congress to fight against British forces and their allies as part of the American Revolutionary ...

was formed.