The ''

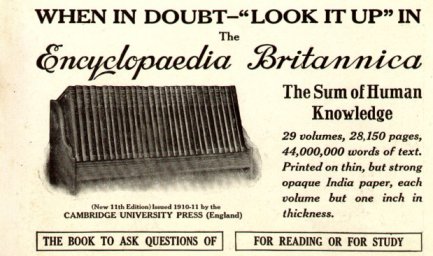

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' has been published continuously since 1768, appearing in fifteen official editions. Several editions have been amended with multi-volume "supplements" (third, fifth/sixth), consisted of previous editions with added supplements (10th, and 12th/13th) or gone drastic re-organizations (15th). In recent years, digital versions of the ''Britannica'' have been developed, both online and on

optical media

An optical disc is a flat, usuallyNon-circular optical discs exist for fashion purposes; see shaped compact disc. disc-shaped object that stores information in the form of physical variations on its surface that can be read with the aid o ...

. Since the early 1930s, the ''Britannica'' has developed several "spin-off" products to leverage its reputation as a reliable reference work and educational tool.

The encyclopedia as known up to 2012 was incurring unsustainable losses and the print editions were ended, but it continues on the Internet.

Historical context

Encyclopedias of various types had been published since antiquity, beginning with the collected works of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and the ''

Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

'' of

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, the latter having 2,493 articles in 37 books. Encyclopedias were published in Europe and China throughout the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, such as the ''

Satyricon

The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius in the late 1st century AD, though the manuscript tradition identifi ...

'' of

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (early 5th century), the ''Speculum majus'' (''Great Mirror'') of

Vincent of Beauvais

Vincent of Beauvais ( or ; ; c. 1264) was a Dominican friar at the Cistercian monastery of Royaumont Abbey, France. He is known mostly for his '' Speculum Maius'' (''Great mirror''), a major work of compilation that was widely read in the Middl ...

(1250), and ''Encyclopedia septem tomis distincta'' (''A Seven-Part Encyclopedia'') by

Johann Heinrich Alsted

Johann Heinrich Alsted (March 1588 – November 9, 1638), "the true parent of all the Encyclopedia, Encyclopædias",s:Budget of Paradoxes/O. was a Germany, German-born Transylvanian Saxon Calvinist minister and academic, known for his varied inte ...

(1630). Most early encyclopedias did not include biographies of living people and were written in

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, although some encyclopedias were translated into English, such as ''De proprietatibus rerum (On the properties of things)'' (1240) by

Bartholomeus Anglicus

Bartholomaeus Anglicus (before 1203–1272), also known as Bartholomew the Englishman and Berthelet, was an early 13th-century scholasticism, Scholastic of Paris, a member of the Franciscan order. He was the author of the compendium ''De propri ...

. However, English-composed encyclopedias appeared in the 18th century, beginning with

''Lexicon technicum, or A Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences'' by

John Harris (two volumes, published 1704 and 1710, respectively), which contained articles by such contributors as

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

.

Ephraim Chambers wrote a very popular two-volume ''

Cyclopedia'' in 1728, which went through multiple editions and awakened publishers to the enormous profit potential of encyclopedias. Although not all encyclopedias succeeded commercially, their elements sometimes inspired future encyclopedias; for example, the failed two-volume ''A Universal History of Arts and Sciences'' of

Dennis de Coetlogon (published 1745) grouped its topics into long self-contained treatises, an organization that likely inspired the "new plan" of the ''Britannica''. The first encyclopedia to include biographies of living people was the 64-volume ''

Grosses Universal-Lexicon'' (published 1732–1759) of

Johann Heinrich Zedler

Johann Heinrich Zedler (7 January 1706 in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) – 21 March 1751 in Leipzig) was a bookseller and publisher. His most important achievement was the creation of a German encyclopedia, the '' Grosses Universal-Lexicon (Gre ...

, who argued that death alone should not render people notable.

Earliest editions (first–sixth, 1768–1824)

First edition, 1771

The ''Britannica'' was the idea of

Colin Macfarquhar

Colin Macfarquhar (1744/5 – 2 April 1793) was a Scottish bookseller and printer who is most known for co-founding ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' with Andrew Bell, first published in December 1768. The dates of his birth and death remain uncerta ...

, a bookseller and printer, and

Andrew Bell, an engraver, both of

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. They conceived of the ''Britannica'' as a conservative reaction to the French ''

Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

'' of

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

(published 1751–1766), which was widely viewed as heretical. Ironically, the ''Encyclopédie'' had begun as a French translation of the popular English encyclopedia, ''

Cyclopaedia'' published by

Ephraim Chambers in 1728. Although later editions of Chambers' ''Cyclopaedia'' were still popular, and despite the commercial failure of other English encyclopedias, Macfarquhar and Bell were inspired by the intellectual ferment of the

Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

and thought the time ripe for a new encyclopedia "compiled upon a new plan".

Needing an editor, the two chose a 28-year-old scholar named

William Smellie who was offered 200

pounds sterling

Sterling (Currency symbol, symbol: Pound sign, £; ISO 4217, currency code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound is the main unit of account, unit of sterling, and the word ''Pound (cu ...

to produce the encyclopedia in 100 parts (called "numbers" and equivalent to thick pamphlets), which were later bound into three volumes. The first number appeared on 10 December 1768 in Edinburgh, priced

sixpence or 8

pence

A penny is a coin (: pennies) or a unit of currency (: pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. At present, it is t ...

on finer paper.

The ''Britannica'' was published under the

pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's o ...

"A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland", possibly referring to the many gentlemen who had bought subscriptions.

By releasing the numbers in weekly instalments, the ''Britannica'' was completed in 1771, having 2,391 pages. The numbers were bound in three equally sized volumes covering A–B, C–L, and M–Z; an estimated 3,000 sets were eventually sold, priced at 12 pounds sterling apiece.

also featured 160 copperplate illustrations engraved by Bell. Three of the engravings in the section on midwifery, depicting childbirth in clinical detail, were sufficiently shocking to prompt some readers to tear those engravings out of the volume.

The key idea that set the ''Britannica'' apart was to group related topics together into longer essays, that were then organized alphabetically. Previous English encyclopedias had generally listed related terms separately in their alphabetical order, rather like a modern technical dictionary, an approach that the ''Britannica's management described as "dismembering the sciences".

Although anticipated by

Dennis de Coetlogon, the idea for this "new plan" is generally ascribed to Colin Macfarquhar, although William Smellie claimed it as his own invention.

Smellie wrote most of the first edition, borrowing liberally from the authors of his era, including

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

,

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

,

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

and

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

. He later said:

The vivid prose and easy navigation of the first edition led to strong demand for a second. Although this edition has been faulted for its imperfect scholarship, Smellie argued that the ''Britannica'' should be given the benefit of the doubt:

Smellie strove to make ''Britannica'' as usable as possible, saying that "utility ought to be the principal intention of every publication. Wherever this intention does not plainly appear, neither the books nor their authors have the smallest claim to the approbation of mankind".

The first edition was reprinted in

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, with slight variants on the title page and a different preface, by Edward and Charles Dilly in 1773 and by John Donaldson in 1775.

On the occasion of the

200th anniversary of the 1st edition,

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. published a facsimile of the 1st edition, even including "age spots" on the paper. This has been periodically reprinted and is still part of Britannica's product line.

Second edition, 1783, Supplement 1784

After the success of the first edition, a more ambitious

second edition was begun in 1776, with the addition of history and biography articles.

Smellie declined to be editor, principally because he objected to the addition of biography. Macfarquhar took over the role himself, aided by pharmacist

James Tytler, M.A., who was known as an able writer and willing to work for a very low wage.

Macfarquhar and Bell rescued Tytler from the debtors' sanctuary at Holyrood Palace, and employed him for seven years at 17 shillings per week. Tytler wrote many science and history articles and almost all of the minor articles; by

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

' estimate, Tytler wrote more than three-quarters of the second edition.

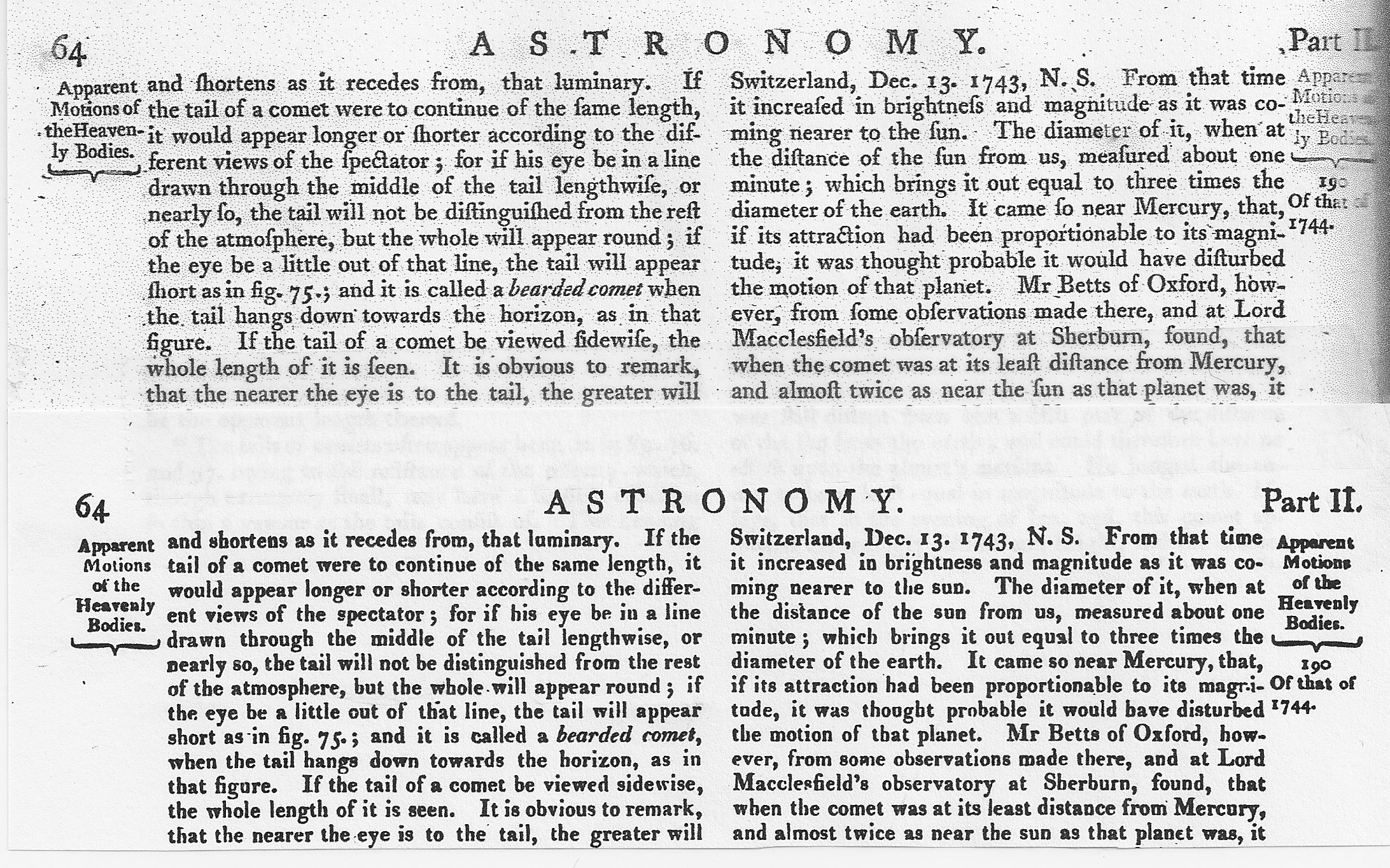

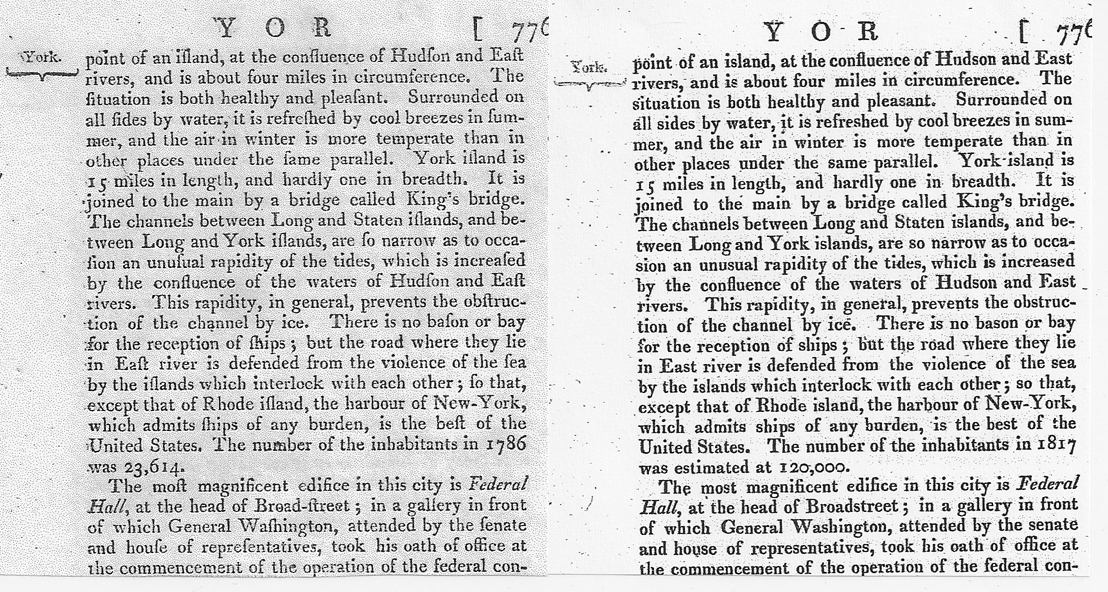

Compared to the first edition, the second had five times as many long articles (150), including "Scotland" (84 pages), "Optics" (132 pages), and "Medicine" (309 pages), which had their own indices. The second edition was published in 181 numbers from 21 June 1777 to 18 September 1784; these numbers were bound into 10 volumes dated 1778–1783, having 8,595 pages and 340 plates again engraved by

Andrew Bell.

A

pagination

Pagination, also known as paging, is the process of dividing a document into discrete page (paper), pages, either electronic pages or printed pages.

In reference to books produced without a computer, pagination can mean the consecutive page num ...

error caused page 8000 to follow page 7099. Most of the maps of this edition (eighteen of them) are found in a single 195-page article, "

Geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

".

The second edition improved greatly upon the first, but is still notable for the large amount of now-archaic information it contained. For example, "Chemistry" goes into great detail on an obsolete system of what would now be called alchemy, in which earth, air, water and fire are named elements containing various amounts of

phlogiston

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

. Tytler also describes the architecture of

Noah's Ark in detail (illustrated with a copperplate engraving). The second edition also reports a cure for

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

:

and a somewhat melancholy article on "

Love

Love is a feeling of strong attraction and emotional attachment (psychology), attachment to a person, animal, or thing. It is expressed in many forms, encompassing a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most su ...

" that persisted in the ''Britannica'' for nearly a century (until its ninth edition):

Like the first edition, the second was sold in sections by subscription at the printing shop of

Colin MacFarquhar

Colin Macfarquhar (1744/5 – 2 April 1793) was a Scottish bookseller and printer who is most known for co-founding ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' with Andrew Bell, first published in December 1768. The dates of his birth and death remain uncerta ...

. When finished in 1784, complete sets were sold at Charles Elliot's bookshop in Edinburgh for 10 pounds, unbound. More than 1,500 copies of the second edition were sold this way by Elliot in less than one year, making the second edition enough of a financial success that a more ambitious third edition was begun a few years later.

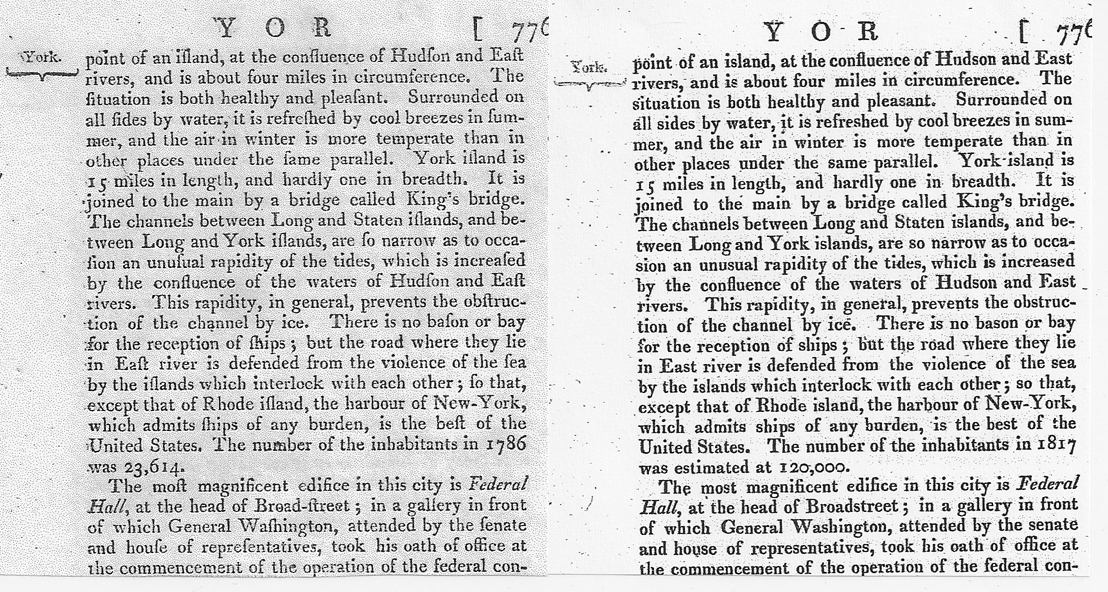

The long period of time during which this edition was written makes the later volumes more updated than the earlier ones. Volume 10, published in 1783 after the

Revolutionary War was over, gives in the entry for Virginia: "Virginia, late one of the British colonies, now one of the United States of North America..." but the entry in Volume 2 for Boston, published in 1778, states: "Boston, the capital of New England in North America, ....The following is a description of this capital before the commencement of the present American war."

The causes of the

Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

are outlined concisely by Tytler in the article "Colonies" thus:

A 204-page appendix, written in 1784, is found at the end of Vol. 10. It does not have its own title page, but merely follows with pagination continuing from 8996 to 9200. The appendix introduces articles on Entomology, Ichthyology, Weather, Hindus (spelled Gentoos), and others, and contains many new biographies, including one of Captain James Cook. It curiously contains 25 new pages on Air, which give very little new information about air itself, but mainly cover hot air ballooning, one of Tytler's hobbies. The first page of the supplement begins with the words "Appendix containing articles omitted and others further explained or improved, together with corrections of errors and of wrong references." The appendix also includes 10 plates, namely CCCXIV to CCCXXIII.

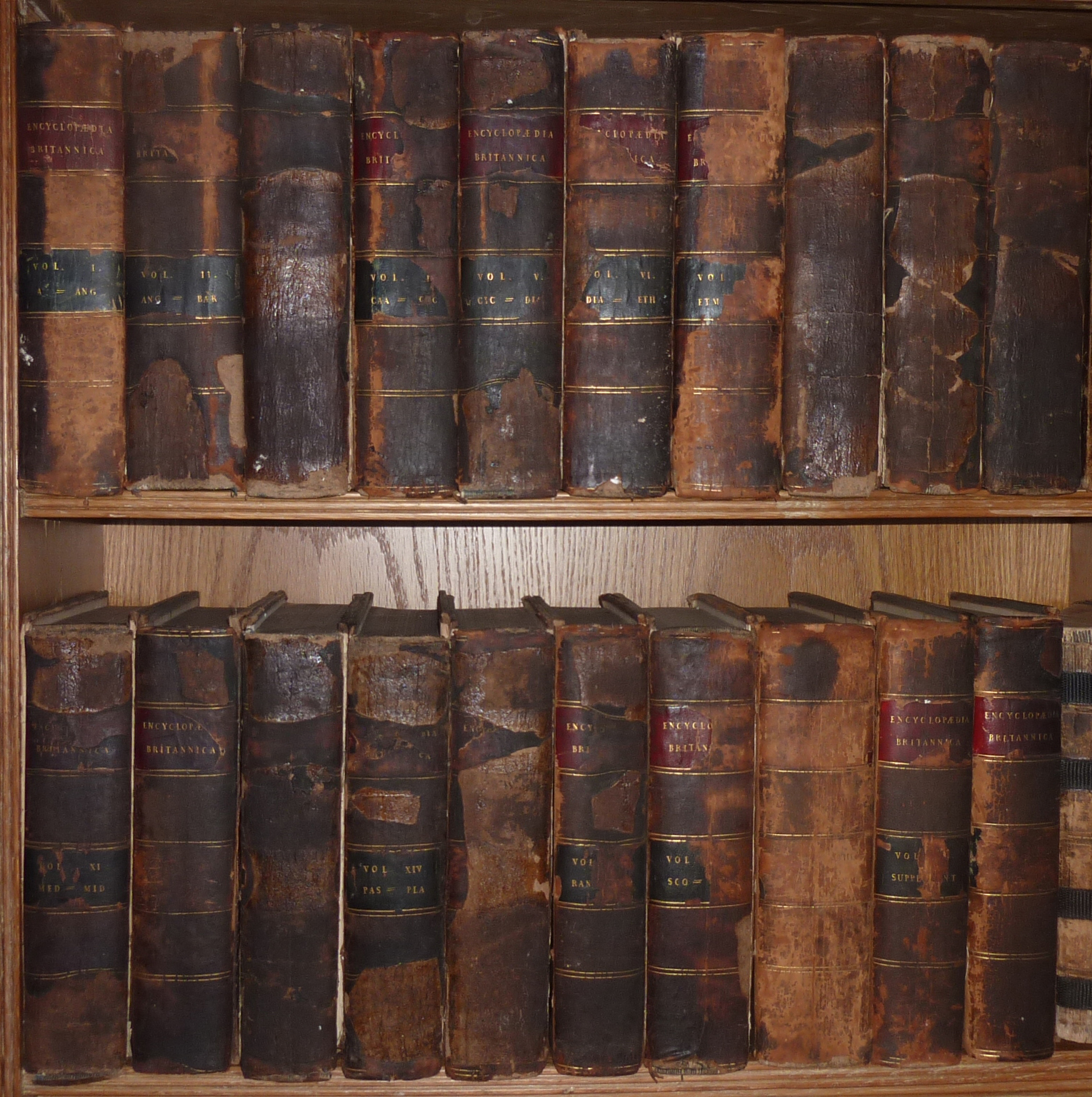

Third edition, 1797

The third edition was published from 1788 to 1797 in 300 weekly numbers (1 shilling apiece); these numbers were collected and sold unbound in 30 parts (10 shilling, sixpence each), and finally in 1797 they were bound in 18 volumes with 14,579 pages and 542 plates, and given title pages dated 1797 for all volumes.

Macfarquhar again edited this edition up to "Mysteries" but died in 1793 (aged 48) of "mental exhaustion"; his work was taken over by

George Gleig, later Bishop Gleig of Brechin (consecrated 30 October 1808).

James Tytler again contributed heavily to the authorship, up to the letter M.

Andrew Bell, Macfarquhar's partner, bought the rights to the ''Britannica'' from Macfarquhar's heirs.

Nearly doubling the scope of the second edition, Macfarquhar's encyclopedic vision was finally realized. Recruited by Gleig, several illustrious authorities contributed to this edition, such as

Thomas Thomson, who introduced modern chemical nomenclature in a chart appended to the Chemistry article, and would go on to re-write that article in the 1801 supplement (see below), and

John Robison, Secretary of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, who wrote several well-regarded articles on sciences then called

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

. The third edition established the foundation of the ''Britannica'' as an important and definitive reference work for much of the next century. This edition was also enormously profitable, yielding 42,000 pounds sterling profit on the sale of roughly 10,000 copies. The third edition began the tradition (continued to this day) of dedicating the ''Britannica'' to the reigning British monarch, then

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. In the Supplement to the Third Edition, Gleig called him "the Father of Your People, and enlightened Patron of Arts, Sciences and Literature", and expressed:

The

third edition is also famous for its bold article on "Motion", which erroneously rejects

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

's theory of

gravitation

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

. Instead, Gleig, or more likely,

James Tytler, wrote that gravity is caused by the

classical element of fire. He seems to have been swayed by

William Jones' ''Essay on the First Principles of Natural Philosophy'' (1762), which in turn was based on

John Hutchinson's MA thesis, ''Moses' Principia'', which was written in 1724 but rejected by

Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

. Nevertheless, Gleig was sanguine about the errors of the third edition, echoing

William Smellie's sentiment in the first edition quoted above:

The first "American" encyclopedia, ''

Dobson's Encyclopædia

''Dobson's Encyclopædia'' was the first encyclopedia issued in the newly independent United States, United States of America, published by Thomas Dobson (printer), Thomas Dobson from 1789 to 1798. ''Encyclopædia'' was the full title of the w ...

'', was based almost entirely on the third edition of the ''Britannica'' and published at nearly the same time (1788–1798), together with an analogous supplement (1803), by the Scottish-born printer,

Thomas Dobson. The first United States

copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, ...

law was passed on 30 May 1790—although anticipated by Section 8 of Article I of the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

(ratified 4 March 1789)—but did not protect foreign publications such as the ''Britannica''. Unauthorized copying of the ''Britannica'' in America was also a problem with the ninth edition (1889). Unlicensed copies were also sold in Dublin by James Moore under the title, ''Moore's Dublin Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica''; this was an exact reproduction of the ''Britannica''

's 3rd edition.

By contrast, Dobson's work had various corrections and amendments for American readers.

Supplement to the third edition, 1801, 1803

A two-volume supplement to the

third edition was published in 1801, having 1,624 pages and 50 copperplates by D. Lizars. A revised edition was published in 1803. This supplement was published by a wine-merchant,

Thomas Bonar, the son-in-law of the ''Britannica's'' owner

Andrew Bell; unfortunately, the two men quarreled and they never spoke for the last ten years of Bell's life (1799–1809). Bonar was friendly to the article authors, however, and conceived the plan of paying them as well as the article reviewers, and of allowing them to retain copyright for separate publication of their work.

The ''Britannica'' explicitly positioned itself as a conservative publication in reaction to the radical French ''

Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

'' of

Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during t ...

published between 1751 and 1766.

In the royal dedication penned on 10 December 1800, Gleig elaborated on the editorial purpose of the ''Britannica''

Fourth edition, 1810

The fourth edition was begun in 1800 and completed in 1810, comprising 20 volumes with 16,033 pages and 581 plates engraved by

Andrew Bell. As with the third edition, in which title pages were not printed until the set was complete, and all volumes were given title pages dated 1797, title pages for the fourth edition were sent to bookbinders in 1810, dated that year for all volumes. The editor was

James Millar, a physician, who was good at scientific topics but criticized for being "slow & dilatory & not well qualified". The mathematical articles of Prof. Wallace were widely praised in the fourth edition. Overall, the fourth edition was a mild expansion of the third, from 18 to 20 volumes, and was updated in its historical, scientific, and biographical articles.

Some of the long articles were entirely re-written for the fourth edition. For example, the 56-page "Botany" of the third edition was replaced in the fourth with a 270-page version by moving all the individual plant articles into one. Conversely, the 53-page "

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

" of the third was removed, and replaced by the note "see Gilding, Parting, Purifying, Refining, Smithery." The article "Chemistry," which was 261 pages long in the third, written by

James Tytler, and had been re-written in that edition's supplement as a 191-page treatise by

Thomas Thomson, appears in the fourth edition as an entirely new 358-page article, which, according to the preface to the fifth edition, was authored by Millar himself. The new treatise was necessary because the copyright to the supplement to the third, which included Thomson's excellent treatise, was not owned by Britannica. (Thomson would much later author the article for the seventh edition). The article "Electricity", 125 pages in the third edition, was completely re-written for the fourth edition and was 163 pages. By contrast, the 125-page "

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

" of the third was largely unchanged for the fourth, and the 306-page "Medicine" of the third was only superficially edited in the fourth and of roughly equal length. (Medicine had been a similar 302 pages in the second edition). The 79-page "Agriculture" of the third was entirely and excellently re-written, and is 225 pages, for the fourth edition. Sixty pages of new information were added onto the end of "America," which grew to 138 pages, with an index and new maps. "

Entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

" was expanded from eight pages and one plate in the third edition to 98 pages and four plates in the fourth, with a three-page index. Human "Physiology" was entirely re-written, and went from 60 pages to 80, with an index. "Physics," on the other hand, is unchanged from the third.

In addition, some long articles appear for the first time in the fourth edition. "Geology" is new, even though the word had been coined in 1735. Accordingly, the third edition's 30-page entry "Earth," as well as its 24-page article "Earthquake," and the geological sections of its article "

Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

", were dropped, as these topics are found in the fourth edition's newly written article, which is 78 pages long and has its own index. For other examples, the fourth edition has a 96-page article "

Conchology

Conchology, from Ancient Greek κόγχος (''kónkhos''), meaning "cockle (bivalve), cockle", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of mollus ...

", which listing does not appear in the third or its supplement, and "

Erpetology", 60 pages long in the fourth edition, with a 3-page index, is a new listing as well. After "Science" is a new 24-page article "Amusements In Science", which is a virtual

Mr. Wizard for the opening of the 19th century.

The majority of copy in the fourth edition, however, is unchanged from the third. Large blocks of text were carried over, line-by-line, unchanged in their typesetting, with some minor editing here and there. For example, the "Boston" article in the third edition contains the sentence, "The following is a description of this capital before the commencement of the present American war." This line is exactly as it had appeared in the second edition, which was written during the war. (The war had been over for years when the third edition was published). In the fourth edition, the word "present" was replaced with "late", the rest of the article remaining entirely unchanged. The article "America" reprinted the entire 81 pages of the third edition, but appended 52 new pages after it, and an index for the 133-page article.

The copyright of the material in the supplement to the third edition was held by

Thomas Bonar, who asked 20,000 pounds sterling for it, which Bell declined. The supplemental material was licensed for the fourth edition for 100 pounds, but this copyright issue remained a problem through the sixth edition and the material was not used. The supplements had to be purchased separately.

Fifth edition, 1817

Andrew Bell died in 1809, one year before the fourth edition was finished. In 1815, his heirs began producing the fifth edition but sold it to

Archibald Constable

Archibald David Constable (24 February 1774 – 21 July 1827) was a Scottish publisher, bookseller and stationer.

Life

Constable was born at Carnbee, Fife, son of the land steward to the Earl of Kellie.

In 1788 Archibald was apprenticed to ...

, who finished it; Millar was again the editor. Completed in 1817, the fifth edition sold for 36 pounds sterling (''2011: £'') and consisted of 20 volumes with 16,017 pages and 582 plates. In 1816, Bell's trustees sold the rights to the ''Britannica'' for 14,000 pounds to Archibald Constable, an apprentice bookseller, who had been involved in its publication from 1788. To secure the copyrights for the third edition supplement, Constable gave Bonar a one-third stake in the ''Britannica''; after Bonar's death in 1814, Constable bought his rights to the ''Britannica'' for 4,500 pounds sterling.

The fifth edition was a corrected reprint of the fourth; there is virtually no change in the text. The errata are listed at the end of each volume of the fourth edition, and corrected in the fifth, but the number of errata is small and in some volumes there are none. The plates and plate numbers are all the same, but with the name A. Bell replaced with W. Archibald or other names on all plates, including the maps. Some of the plates have very minor revisions, but they are all basically Bell's work from the fourth or earlier editions, and these new names were probably added for business reasons involving copyright royalties. W. Archibald was probably Constable himself.

Being a reprint of the fourth, set in the same type, Encyclopædia Britannica's fifth edition was one of the last publications in the English language to use the

long s

The long s, , also known as the medial ''s'' or initial ''s'', is an Archaism, archaic form of the lowercase letter , found mostly in works from the late 8th to early 19th centuries. It replaced one or both of the letters ''s'' in a double-''s ...

in print. The long s started being phased out of English publications shortly after the turn of the 19th century, and by 1817 it was archaic. The Supplement To The Fifth edition (see below), as well as the sixth edition, used a modern font with a short s.

While the sixth volume of the fifth edition was being printed, Constable became owner of Britannica, as well as Bonar's third edition supplements. Legal disputes over the copyright of the third edition supplements continued, however, and for this reason a new supplement was written by Constable's company, which was completed in 1824.

Supplement to the fifth edition, 1824 (later known as the supplement to the fourth, fifth and sixth editions)

After securing sole-ownership rights in December 1816, Constable began work on a supplement to the fifth edition, even before the fifth edition had been released (1817). The supplement was completed in April 1824, consisting of six volumes with 4,933 pages, 125 plates, 9 maps, 3 "dissertations" and 160 biographies, mainly of people who had died within the preceding 30 years.

This supplement contained a rudimentary form of an index, listing the 669 articles in alphabetical order at the end of volume six, by volume but not page number, but it did not contain any sort of cross referencing. The index was called "Table of the Articles and Treatises Contained in This Work" and was 9 pages long. It was nothing to be compared to a typical encyclopedia index, such as the ones found at the end of the seventh and further editions of Britannica.

This supplement had remarkably illustrious contributors. Constable was friends with Sir

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, who contributed the articles "Chivalry", "Romance", and "Drama". To edit the supplement, Constable hired

Macvey Napier, who recruited other eminent contributors such as Sir

Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several Chemical element, e ...

,

Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French people, French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, ma ...

,

James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

,

William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt (10 April 177818 September 1830) was an English essayist, drama and literary criticism, literary critic, painter, social commentator, and philosopher. He is now considered one of the greatest critics and essayists in the history ...

,

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

, and

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

.

Peter Mark Roget

Peter Mark Roget ( ; 18 January 1779 – 12 September 1869) was a British physician, natural theologian, Lexicography, lexicographer, and founding secretary of The Portico Library. He is best known for publishing, in 1852, the ''Roget's Thesau ...

, compiler of the famous

Roget's Thesaurus

''Roget's Thesaurus'' is a widely used English-language thesaurus, created in 1805 by Peter Mark Roget (1779–1869), British physician, natural theologian and lexicographer.

History

It was released to the public on 29 April 1852. Roget was ...

and a former secretary of the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, contributed the entry for

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

.

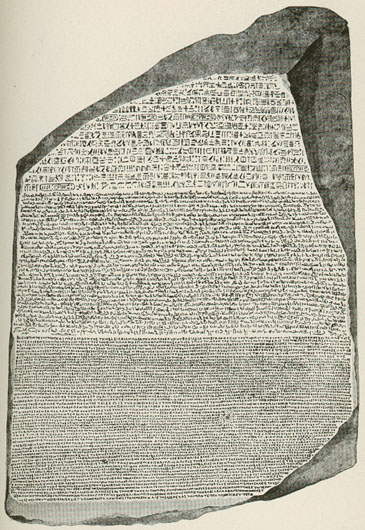

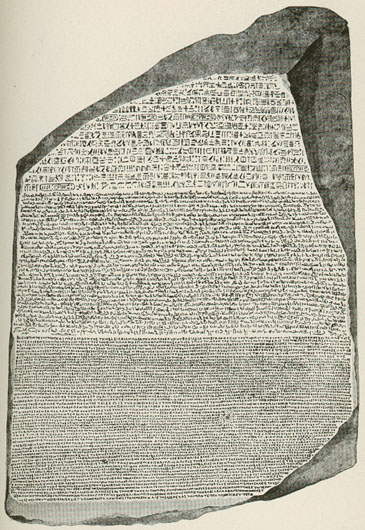

Thomas Young's article on

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

included the translation of the

hieroglyphics

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct characters.I ...

on the

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty of ancient Egypt, Egypt, on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts ...

.

The supplement was compiled, for the first five volumes, at a pace which would have given it more than the 6 volumes it eventually would consist of; the alphabet from A-M was put into those five. It was apparently rushed to completion with volume 6, which contained the rest of the alphabet, viz:

*Vol. I: A–ATW, 648 pages.

*Vol. II: AUS–CEY, 680 pages.

*Vol. III: CHE–ECO, 726 pages.

*Vol. IV: EDI–HOR, 708 pages.

*Vol. V: HUN–MOL, 586 pages.

*Vol. VI: NAI–Z, 863 pages.

Sixth edition, 1823

Constable also produced the sixth edition, which was completed in May, 1823. It was published in 40 half-volume parts, priced 16 shillings in boards (32 pounds for the set). The editor was

Charles Maclaren. The sixth edition was a reprint of the fifth with a modern typeface. It even used the preface to the fifth edition, dated December 1, 1817, as its own. Only the short page, "Advertisement To The Sixth Edition", which was bound in volume 1 after the forward and dated January, 1822, set it apart. In that advertisement, it is claimed that some geographical articles would be updated, and that the articles in the supplement to the third edition would be inserted into the encyclopedia in their proper alphabetical places. Although the advertisement claimed that these articles would be included in this manner, they were not, and the author of the preface to the seventh edition states that none of this material entered the main body until that edition, and even gives a list of the articles which were.

Almost no changes were made to the text, it was basically a remake of the fifth with very minor updates. All in all, the fourth, fifth, and sixth editions are virtually the same as each other. Rather than revising the main text of the encyclopedia with each edition, Constable chose to add all updates to the supplement. It's probable that the sixth edition only exists because of the need to remove the

long s

The long s, , also known as the medial ''s'' or initial ''s'', is an Archaism, archaic form of the lowercase letter , found mostly in works from the late 8th to early 19th centuries. It replaced one or both of the letters ''s'' in a double-''s ...

, which had gone out of style, from the font, which required the whole encyclopedia to be re-typeset.

The Supplement to the fifth edition was finished in 1824, and was sold with those sets, as well as with sets of the sixth edition, to be delivered at its completion. This supplement curiously was started during the production of the fifth edition but was not finished until after the 6th was completed. It also was sold as a unit for owners of the fourth edition, and became known as "Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th edition".

Unfortunately, Constable went bankrupt on 19 January 1826 and the rights to the ''Britannica'' were sold on auction; they were eventually bought on 16 July 1828 for 6,150

pounds sterling

Sterling (Currency symbol, symbol: Pound sign, £; ISO 4217, currency code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound is the main unit of account, unit of sterling, and the word ''Pound (cu ...

by a partnership of four men:

Adam Black (a publisher), Alexander Wight (a banker), Abram Thomson (a bookbinder) and Thomas Allen, the proprietor of the ''

Caledonian Mercury

The ''Caledonian Mercury'' was a newspaper in Edinburgh, Scotland, published three times a week between 1720 and 1867. In 2010 an online publication launched using the name.

17th century

A short-lived predecessor, the '' Mercurius Caledonius'', ...

''. Not long after, Black bought out his partners and ownership of the ''Britannica'' passed to the Edinburgh publishing firm of

A & C Black

A & C Black is a British book publishing company, owned since 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing. The company is noted for publishing ''Who's Who'' since 1849 and the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' between 1827 and 1903. It offers a wide variety of boo ...

.

Britannica by the sixth edition was in some regards hopelessly out of date. The supplement to the third edition contained updates which were not included in it, and which had become dated themselves anyway, the fourth edition expanded the text somewhat but revised very little, and the fifth and sixth were just reprints of the fourth. The supplement to the fourth/fifth/sixth edition addressed the issue of updates in a clumsy way, often referring back to the encyclopedia, essentially making the reader look everything up twice. What was needed was a completely new edition from the ground up. This was to be accomplished with the magnificent seventh edition.

A. and C. Black editions (seventh–ninth, 1827–1901)

Seventh edition, 1842

The seventh edition was begun in 1827 and published from March 1830 to January 1842, although all volumes have title pages dated 1842. It was a new work, not a revision of earlier editions, although some articles from earlier editions and supplements are used. It was sold to subscribers in monthly "parts" of around 133 pages each, at 6 shilling per part, with 6 parts combined into 800 page volumes for 36 shillings. The promise was made in the beginning that there would be 20 volumes, making the total £36 for the set. Volume 1 was only 5 parts, entirely made up of dissertations. Volume 2, in 6 parts, was the beginning of alphabetical listings. The 12th part, another dissertation, was ready in 1831, and would have been the first part of volume 3, but the publishers put it into a separate volume at 12 shillings. In total the subscribers wound up paying for 127 parts (£38, two shillings).

It was edited by

Macvey Napier, who was assisted by

James Browne, LLD. It consisted of 21 numbered volumes with 17,101 pages and 506 plates. It was the first edition to include a general index for all articles, a practice that was maintained until 1974. The index was 187 pages, and was either bound alone as an unnumbered thin volume, or was bound together with volume I. Many illustrious contributors were recruited to this edition, including Sir

David Brewster

Sir David Brewster Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order, KH President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, PRSE Fellow of the Royal Society of London, FRS Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, FSA Scot Fellow of the Scottish Society of ...

,

Thomas de Quincey

Thomas Penson De Quincey (; Thomas Penson Quincey; 15 August 17858 December 1859) was an English writer, essayist, and literary critic, best known for his ''Confessions of an English Opium-Eater'' (1821).Eaton, Horace Ainsworth, ''Thomas De Q ...

,

Antonio Panizzi and

Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson , (honoris causa, Hon. causa) (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of hi ...

.

James Wilson did all of Zoology, Hampden did all of Greek philosophy, and

William Hosking contributed the excellent article Architecture.

Thomas Thomson, who wrote Chemistry for the third edition supplement 40 years earlier, was recruited to write that article again for the seventh edition. Mathematical diagrams and illustrations were made from woodcuts, and for the first time in Britannica's history, were printed on the same pages as the text, in addition to the copperplates.

The seventh edition, when complete, went on sale for £24 per set. However, Adam Black had invested more than £108,766 in its production: £5,354 for advertising, £8,755 for editing, £13,887 for 167 contributors, £13,159 for plates, £29,279 for paper, and £19,813 for the printing.

In the end, roughly 5,000 sets were sold but Black considered himself well-rewarded in intellectual prestige.

Title pages for all volumes were printed in 1842 and delivered with the completed set. An index to the entire set was created that year as well, and was the first of its kind for Britannica. Being only 187 pages long, it did not warrant its own volume, and was sent to bookbinders with instructions to include it at the beginning of volume 1, the dissertations volume, which had been printed in 1829. This same arrangement would also be used for the eighth edition, but not the ninth.

Eighth edition, 1860

The eighth edition was published from 1853 to 1860, with title pages for each volume dated the year that volume was printed. It contained 21 numbered volumes, with 17,957 pages and 402 plates. The index, published in 1861, was 239 pages, and was either bound alone as an unnumbered 22nd volume, or was bound together with volume I, the dissertations volume. Four of these dissertations were carried over from the seventh edition, and two were new to the eighth. The five included in volume 1 of the eighth (1853) were authored by Dugald Stewart, James Mackintosh, Richard Whately, John Playfair, and John Leslie, in that order, with the Whately work being a new one. A sixth dissertation, by J. D. Forbes, was issued in 1856, in a separate quarto volume, "gratis, along with Vol. XII".

The alphabetical encyclopedia began at the beginning of volume 2. The price was reduced to 24 shillings per volume, cloth-bound. In addition to the Edinburgh sets, more sets were authorized by Britannica to the London publishers Simpkin, Marshall and Company, and to

Little, Brown and Company

Little, Brown and Company is an American publishing company founded in 1837 by Charles Coffin Little and James Brown in Boston. For close to two centuries, it has published fiction and nonfiction by American authors. Early lists featured Emil ...

of Boston.

Since

Macvey Napier died in 1847, Adam Black selected for its editor

Thomas Stewart Traill

Thomas Stewart Traill (29 October 1781 – 30 July 1862) was a British physician, chemist, meteorologist, zoologist and scholar of medical jurisprudence. He was the grandfather of the physicist, meteorologist and geologist Robert Traill Omon ...

, a professor of medical jurisprudence at Edinburgh University. When Traill fell ill, he was assisted by a young Scottish philosopher, John Downes. Black was able to hold costs to roughly £75,655. This edition began the tradition of a contributors' banquet to celebrate the edition's completion (5 June 1861).

The eighth edition is a thorough revision, even more so than the Seventh. Some long articles were carried over from the seventh edition, but most were completely re-written, and new articles by illustrious contributors were added. In all, there were 344 contributors, including

Lord Macaulay,

Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

,

Robert Chambers, the Rev.

Charles Merivale

Charles Merivale (8 March 1808 – 27 December 1893) was an English historian and churchman, for many years dean of Ely Cathedral. He was one of the main instigators of the The Boat Race, inaugural Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race which took p ...

,

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

, Baron

Robert Bunsen

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (;

30 March 1811

– 16 August 1899) was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and discovered caesium (in 1860) and rubidium (in 1861) with the physicist Gustav Kirchhoff. The Bu ...

, Sir

John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

, Professors

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

,

John Stuart Blackie and

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin).

Photography

Photography is the visual arts, art, application, and practice of creating images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is empl ...

is listed for the first time. This edition also featured the first American contributor to the ''Britannica'',

Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mas ...

, who wrote a 40,000-word hagiographic biography of

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

The consequences of reducing the costs of production of the eighth edition can be seen today in surviving sets. With only 402 plates, this edition has the fewest since the second edition, and far fewer woodcuts within the text pages were used than in the seventh edition. The maps are all reprinted from the seventh edition, even the ones that should have been updated. In the first few volumes, a sheet of onion-skin paper faces each plate, but after volume 6, they were eliminated. To save money, the end pages and covers were not marbled, as this was an expensive process. Finally, the end pages contain advertisements for other products sold by A & C. Black, such as atlases and travel guides, and advertisements encouraging subscribers to continue their enrollments.

Ninth edition, 1875–1889

The landmark ninth edition, often called "the Scholar's Edition",

was published from January 1875 to 1889 in 25 volumes, with volume 25 the index volume. Unlike the first two Black editions, there were no preliminary dissertations, the alphabetical listing beginning in volume 1. Up to 1880, the editor, and author of the Foreword, was

Thomas Spencer Baynes

Thomas Spencer Baynes (24 March 1823 – 31 May 1887) was an English writer and scholar. He was best known for serving as the Editor-in-Chief of ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. He was also well known for his essays in the ''Edinburgh Review'' and ...

—the first English-born editor after a series of Scots—and

W. Robertson Smith afterwards. An intellectual prodigy who mastered advanced scientific and mathematical topics, Smith was a professor of theology at the

Free Church College in

Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

, and was the first contributor to the ''Britannica'' who addressed the historical interpretation of the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, a topic then already familiar on the Continent of Europe. Smith contributed several articles to the ninth edition, but lost his teaching position on 24 May 1881, due to the controversy his (ir)religious articles aroused; he was immediately hired to be joint editor-in-chief with Baynes.

The ninth and 11th editions are often lauded as high points for scholarship; the ninth included yet another series of illustrious contributors such as

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

(article on "Evolution"),

Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh ( ; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919), was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 "for his investigations of the densities of the most important gases and for his discovery ...

(articles on "Optics, Geometrical" and "Wave Theory of Light"),

Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 – 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist and critic. He wrote many plays – all tragedies – and collections of poetry such as '' Poems and Ballads'', and contributed to the Eleve ...

(article on "John Keats"),

William Michael Rossetti

William Michael Rossetti (25 September 1829 – 5 February 1919) was an English writer and critic.

Early life

Born in London, Rossetti was a son of exiled Italian scholar Gabriele Rossetti and his wife Frances Polidori, Frances Rossetti '' ...

,

Amelia Edwards

Amelia Ann Blanford Edwards (7 June 1831 – 15 April 1892), also known as Amelia B. Edwards, was an English novelist, journalist, traveller and Egyptologist. Her literary successes included the ghost story ''The Phantom Coach'' (1864), the nov ...

(article on "Mummy"),

Prince Kropotkin (articles on "Moscow", "Odessa" and "Siberia"),

James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folkloristJosephson-Storm (2017), Chapter 5. influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

...

(articles on "Taboo" and "Totemism"),

Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a folkloristics, collector of folklore, folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectur ...

(article on "Apparitions"),

Lord Macaulay,

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

(articles on "Atom" and "Ether"),

Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (26 June 182417 December 1907), was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer. Born in Belfast, he was the Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), professor of Natur ...

(articles on "Elasticity" and "Heat") and

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

(article on "Mural Decoration").

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

, then 25, contributed an article about

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

that, being unenthusiastic, was never printed.

There were roughly 1100 contributors altogether, a handful of whom were women; this edition was also the first to include a significant article about women ("Women, Law Relating to"). Evolution was listed for the first time, in the wake of

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's writings, but the subject was treated as if still controversial, and a complete working of the subject would have to wait for the 11th edition. The eighth edition has no listing for the subject at all.

Compared to the eighth edition, the ninth was far more luxurious, with thick boards and high-quality leather bindings, premier paper, and a production which took full advantage of the technological advances in printing in the years between the 1850s and 1870s. Great use was made of the new ability to print large graphic illustrations on the same pages as the text, as opposed to limiting illustrations to separate copperplates. Although this technology had first been used in a primitive fashion the seventh edition, and to a much lesser extent in the 8th, in the ninth edition there were thousands of quality illustrations set into the text pages, in addition to the plates. The ninth edition was a critical success, and roughly 8,500 sets were sold in Britain.

A & C Black

A & C Black is a British book publishing company, owned since 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing. The company is noted for publishing ''Who's Who'' since 1849 and the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' between 1827 and 1903. It offers a wide variety of boo ...

authorized the American firms of

Charles Scribner's Sons

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City that has published several notable American authors, including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjori ...

of New York,

Little, Brown and Company

Little, Brown and Company is an American publishing company founded in 1837 by Charles Coffin Little and James Brown in Boston. For close to two centuries, it has published fiction and nonfiction by American authors. Early lists featured Emil ...

of Boston, and Samuel L. Hall of New York, to print, bind and distribute additional sets in the United States, and provided them with stereotype plates for text and graphics, specifications on the color and tanning quality of the leather bindings, etc., so the American-produced sets would be identical to the Edinburgh sets except for the title pages, and that they would be of the same high quality as the Edinburgh sets. Scribner's volumes and Hall volumes were often mixed together in sets by N.Y. distributors and sold this way as they were interchangeable, and such sets are still found this way. A total of 45,000 authorized sets were produced this way for the US market.

Scribners' claimed U.S. copyright on several of the individual articles.

In spite of this, ''several hundred thousand'' cheaply produced bootlegged copies were also sold in the U.S., which still did not have copyright laws protecting foreign publications.

Famous infringers of that era include the

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

n Joseph M. Stoddart, who employed a spy in the ''Britannica's'' own printshop, Neill and Company, in Edinburgh. The spy would steal the proofreader's copies and send them by fastest mail to the United States, allowing Stoddart to publish his version simultaneously with the ''Britannica'' and at nearly half the price ($5 versus $9 per volume). His right to do so was upheld in an infamous decision by Justice Arthur Butler who argued

Another successful infringer was Henry G. Allen, who developed a photographic reproduction method for the ''Britannica'' and charged only half as much as Stoddart ($2.50 per volume). Other people alleged to have copied the ninth edition included

John Wanamaker

John Wanamaker (July 11, 1838December 12, 1922) was an American merchant and religious, civic and political figure, considered by some to be a proponent of advertising and a "pioneer in marketing". He served as United States Postmaster General ...

and the Reverend

Isaac Kaufmann Funk of the

Funk and Wagnalls encyclopedia. Richard S. Pearle & Co. of Chicago photoengraved some sets in 1891, and added three volumes of "American Revisions and additions," the first two in 1891 and the third in 1892. In 1893, they published sets with volumes 1–24 from the original Britannica, the three "American" volumes 25–27, and the index as Vol. 28. Some copies of this version say they were printed by Werner, also of Chicago, and from 1902 to 1907 Werner printed the commonly found "New Werner Edition," of 30 volumes (24 volumes plus five ''New American Supplement'' volumes and a new index for all 29 volumes). In 1890, James Clarke published the ''Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, Revised and Amended'' which was only 10 volumes, as was the 1895 Belford-Clark issue by the same name (Chicago).

In addition to American unauthorized copies, there were American supplements which were written to be appended to authorized copies of Britannica. The Hubbard Brothers of Philadelphia produced a 5-volume American supplement between 1882 and 1889, in quality leather bindings designed to match the authorized volumes in appearance. Of good scholarship, it contained biographies of Americans and geographies of US places, as well as other US interests not mentioned in the main encyclopedia.

In 1896, Scribner's Sons, which had claimed US copyright on many of the articles, obtained court orders to shut down bootlegger operations, some of whose printing plates were melted down as part of the enforcement.

Publishers were able to get around this order, however, by re-writing the articles that Scribner's had copyrighted; for example, the "United States" article in Werner's 1902 unlicensed edition was newly written and copyrighted by R.S. Pearle.

In 1903,

Saalfield Publishing

The Saalfield Publishing Company published children's books and other products from 1900 to 1977. It was once one of the largest publishers of children's materials in the world.

The company was founded in 1900 in Akron, Ohio, by Arthur J. Saalfi ...

published the ''Americanized''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

in 8 volumes with a 4 volume supplement (when the British edition had 24 volumes). The

Encyclopædia Britannica Company had acquired all the rights to the encyclopedia in America. In addition,

D. Appleton & Company claimed that the 4 volume supplement used material from ''

Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography

''Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography'' is a six-volume collection of biography, biographies of notable people involved in the history of the New World. Published between 1887 and 1889, its unsigned articles were widely accepted as autho ...

''. To avoid further litigation, the suit against Saalfield Publishing was settled in court "by a stipulation in which the defendants agree not to print or sell any further copies of the offending work, to destroy all printed sheets, to destroy or melt the portions of the plates from which the infringing matter in the Supplement as it appears in the ''Americanized

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' has been printed, and to pay D. Appleton & Co. the sum of $2000 damages."

Horace Everett Hooper

Horace Everett Hooper (December 8, 1859 – June 13, 1922) was the publisher of ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' from 1897 until his death.

Early life

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, he quit school at the age of 16, and after gaining experience ...

was an American businessman, and a close associate of James Clarke, one of the leading American bootleggers. Hooper recognized the potential profit in the ''Britannica'' and, again in 1896, learned that both the ''Britannica'' and ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' of London were in financial straits. Hooper formed a partnership with Clarke, his brother George Clarke, and

Walter Montgomery Jackson to sell the ''Britannica'' under the sponsorship of ''The Times'', meaning that ''The Times'' would advertise the sale and lend its respectable name. Hooper and his energetic advertising manager, Henry Haxton, introduced many innovative sales methods: full-page advertisements in ''The Times'', testimonials from celebrities, buying on installment plans, and a long series of so-called 'final offers'. Although the crass marketing was criticized as inappropriate to the ''Britannica's'' history and scholarship, the unprecedented profits delighted the manager of ''The Times'',

Charles Frederic Moberly Bell,

who assessed Hooper as "a ranker who loved to be accepted as a gentleman. Treat him as a gentleman and one had no trouble with him; treat him as an essentially dishonest ranker and one got all the trouble there was to get." The American partnership sold more than 20,000 copies of the ''Britannica'' in the United States (four runs of 5,000), after which Hooper and Jackson bought out the two Clarke brothers in early 1900.

A & C Black

A & C Black is a British book publishing company, owned since 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing. The company is noted for publishing ''Who's Who'' since 1849 and the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' between 1827 and 1903. It offers a wide variety of boo ...

had moved to London in 1895 and, on 9 May 1901, sold all the rights to the ''Britannica'' to Hooper and Jackson, then living in London.

The sale of the ''Britannica'' to Americans has left a lingering resentment among some British citizens, especially when it is perceived that parochial American concerns are emphasized.

For example, one British critic wrote on the centenary of the sale:

First American editions (10th–14th, 1901–1973)

Tenth edition (supplement to the 9th), 1902–03

Again under the sponsorship of ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' of London, and with Adam & Charles Black in the UK, the new owners quickly produced an 11-volume supplement to the ninth edition; being nine volumes of text, 25–33, a map volume, 34, which was 1 inch taller than the other volumes, and a new index, vol 35, also an inch taller than 25–33, which covered the first 33 volumes (the maps volume 34 had its own index). The editors were

Hugh Chisholm

Hugh Chisholm ( ; 22 February 1866 – 29 September 1924) was a British journalist. He was the editor of the 10th, 11th and 12th editions of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

Life

He was born in London, England, a son of Henry Williams Chisho ...

, Sir

Donald Mackenzie Wallace

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (11 November 1841 – 10 January 1919) was a Scottish public servant, writer, editor and foreign correspondent of ''The Times'' (London).

Early life

Donald Mackenzie Wallace was born to Robert Wallace of Boghead ...

,

Arthur T. Hadley and

Franklin Henry Hooper, the brother of the owner Horace Hooper.

Notable contributors to the 10th edition included

Laurence Binyon

Robert Laurence Binyon, Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (10 August 1869 – 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. Born in Lancaster, Lancashire, Lancaster, England, his parents were Frederick Binyon, ...

,

Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann ( ; ; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics and the statistical ex ...

,

Walter Camp

Walter Chauncey Camp (April 7, 1859 – March 14, 1925) was an American college football player and coach, and sports writer known as the "Father of American Football". Among a long list of inventions, he created the sport's line of scrimmage a ...

(articles on "Base-ball" and "Rowing"),

Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman (; 18 July 1865 – 20 February 1959) was an English playwright, writer and illustrator whose career stretched from the 1890s to the 1950s. He studied art in London and worked largely as an illustrator during the first years o ...

,

Joseph Jefferson,

Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard (22 January 1858 – 11 April 1945), known as Sir Frederick Lugard between 1901 and 1928, was a British soldier, Exploration, explorer of Africa and colonial administrator. He was Governor of Hon ...

,

Frederic William Maitland

Frederic William Maitland (28 May 1850 – ) was an English historian and jurist who is regarded as the modern father of English legal history. From 1884 until his death in 1906, he was reader in English law, then Downing Professor of the Laws ...

,

John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the national park, National Parks", was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologi ...

(article on "Yosemite"),

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

(articles on "Greenland" and "Polar Regions: The Arctic Ocean"),

Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922), was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the ''Daily Mail'' and the ''Daily Mirror'', he was an early developer of popular journal ...

(part of article on "Newspapers"),

Sir Flinders Petrie (part of article on "Egyptology"),

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsyl ...

,

Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch,

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh ( ; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919), was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 "for his investigations of the densities of the most important gases and for his discovery ...

(article on "Argon"),

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

,

Carl Schurz

Carl Christian Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German-American revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He migrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent ...

,

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington and

Sir J. J. Thomson.

Taken together, the 35 volumes were dubbed the "10th edition". The re-issue of the ninth edition under the moniker "10th edition" caused some outrage, since many articles of the ninth edition were more than 25 years old. This led to the popular joke: "''The Times'' is behind the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' and the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' is behind the times."

The 1903 advertising campaign for the 10th edition was an onslaught of

direct marketing

Direct marketing is a form of communicating an offer, where organizations communicate directly to a Target market, pre-selected customer and supply a method for a direct response. Among practitioners, it is also known as ''direct response ...

: hand-written letters, telegrams, limited-time offers, etc.. The following quote, written in 1926, captures the mood

An excellent collection of prospectuses received by a single person (C. L. Parker) in that year has been preserved by the

Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

(catalogued under #39899.c.1). The advertising was clearly targeted at middle and lower-middle-class people seeking to improve themselves.

The advertising campaign was remarkably successful; more than 70,000 sets were sold, bringing in profit of more than £600,000.

When one British expert expressed surprise to

Hooper

''Hooper'' may refer to:

Place names in the United States:

* Hooper, Colorado, town in Alamosa County, Colorado

* Hooper, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Hooper, Nebraska, town in Dodge County, Nebraska

* Hooper, Utah, place in Weber Cou ...

that so many people would want an outdated encyclopedia, he replied: "They didn't; I ''made'' them want it."

Even after the 10th edition was published, some American infringement companies were still printing thousands of copies of the Ninth without the supplements. See above. Some of these companies were adding their own "Americanized" supplements, but none of them reproduced the Tenth. Copyright violation did not end until shortly before the 11th edition came out.

Eleventh edition, 1910