History Of Saint Paul, Minnesota on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fossil Collecting in the Twin Cities Area

Minnesota at a Glance: Minnesota Geological Survey: University of Minnesota. During this time, the

In the decade following its designation as the territorial capital, Saint Paul grew exponentially from 900 in 1849 to 10,000 in 1860. William Williams described this boom town during a visit on June 14, 1849:

In the decade following its designation as the territorial capital, Saint Paul grew exponentially from 900 in 1849 to 10,000 in 1860. William Williams described this boom town during a visit on June 14, 1849:

Minnesota's first newspaper, the ''Minnesota Pioneer'', the forerunner of today's ''

Minnesota's first newspaper, the ''Minnesota Pioneer'', the forerunner of today's ''

As Saint Paul grew, and its close neighbors, Saint Anthony and Minneapolis grew with even greater precipitancy, the docks at "Lower Landing" and "Upper Landing" bustled with activity. The state's population reached 200,000 by 1860, and most of those had arrived by

As Saint Paul grew, and its close neighbors, Saint Anthony and Minneapolis grew with even greater precipitancy, the docks at "Lower Landing" and "Upper Landing" bustled with activity. The state's population reached 200,000 by 1860, and most of those had arrived by  By 1877, the volunteer fire department was disbanded in favor of a paid department. The volunteers had served the city since 1854, but the building boom necessitated moving to a full-time department. Horse-drawn street cars and even a few cable cars covered of city streets by 1880, but by 1891 they were all replaced by electric streetcar lines. The outlying neighborhoods grew out of the placement of the streetcar lines and short lines, Merriam Park in 1882, Macalester Park in 1883, Saint Anthony Park in 1885, and Groveland in 1890. In 1885 a New York reporter wrote that Saint Paul was "another Siberia, unfit for human habitation" in winter. Offended by this attack on their Capital City, the Saint Paul Chamber of Commerce decided to not only prove that Saint Paul was habitable but that its citizens were very much alive during winter, the most dominant season. Thus was born the

By 1877, the volunteer fire department was disbanded in favor of a paid department. The volunteers had served the city since 1854, but the building boom necessitated moving to a full-time department. Horse-drawn street cars and even a few cable cars covered of city streets by 1880, but by 1891 they were all replaced by electric streetcar lines. The outlying neighborhoods grew out of the placement of the streetcar lines and short lines, Merriam Park in 1882, Macalester Park in 1883, Saint Anthony Park in 1885, and Groveland in 1890. In 1885 a New York reporter wrote that Saint Paul was "another Siberia, unfit for human habitation" in winter. Offended by this attack on their Capital City, the Saint Paul Chamber of Commerce decided to not only prove that Saint Paul was habitable but that its citizens were very much alive during winter, the most dominant season. Thus was born the  Convenient transportation and an increasingly dense population contributed to an outbreak of

Convenient transportation and an increasingly dense population contributed to an outbreak of

As

As

Church of Saint Louis King of France

(''French'': L'Eglise de Saint-Louis, Roi de France, which is known commonly today as "the little French church") and was the third Catholic Church built by French Canadians to serve the large French speaking population in the rivertown of Saint Paul at the time and finally the Church of Saint Casimir (and Saint Adalbert's Church), respectively. The German-Catholic Parish at the Church of the Assumption spun off several additional German Parishes: Sacred Heart (1881), Saint Francis de Sales (1884), Saint Matthew (1886), the

online

also reprinted Vol. 4. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1983. * Wills, Jocelyn. ''Boosters, Hustlers, and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883'' (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005). * Wingerd, Mary Lethert. ''Claiming the city: politics, faith, and the power of place in St. Paul'' (2001

online

emphasis on Catholics * Wingerd, Mary Lethert. “Separated at Birth: The Sibling Rivalry of Minneapolis and St. Paul,” ''OAH'' ( February 2007)

*

Ramsey County Historical SocietySt. Paul, Minnesota "History in Images"

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Saint Paul, Minnesota Minneapolis–Saint Paul

Saint Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally ...

is the second largest city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

in the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

of Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

, the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or parish (administrative division), civil parish. The term is in use in five countries: Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, and the United States. An equiva ...

of Ramsey County, and the state capital

Below is an index of pages containing lists of capital city, capital cities.

National capitals

*List of national capitals

*List of national capitals by latitude

*List of national capitals by population

*List of national capitals by area

*List of ...

of Minnesota. The origin and growth of the city were spurred by the proximity of Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint An ...

, the first major United States military installation in the area, as well as by the city's location on the northernmost navigable port of the Upper Mississippi River

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River upstream of St. Louis, Missouri, United States, a city at the confluence of its main tributary, the Missouri River. Historically, it may refer to the area above the Arkansa ...

.

Fort Snelling, originally known as Fort Saint Anthony, was established in 1819, at the confluence of the Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

rivers in order to establish American dominance of the fur-trading industry on the rivers. As the whiskey

Whisky or whiskey is a type of liquor made from Fermentation in food processing, fermented grain mashing, mash. Various grains (which may be Malting, malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, Maize, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky ...

trade started to flourish, military officers in Fort Snelling banned distillers from the land the fort controlled. Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, a retired French Canadian fur trader turned bootlegger, was a particular source of irritation to military officers. In 1838, Parrant moved his bootlegging operation downstream about to Fountain Cave,situated in the north bank of the river near what is now Saint Paul's West Seventh Street neighborhood. There, Parrant established the area which became known as "L'Œil de Cochon" (French for "Pig's Eye") and the new location began to be settled by fellow French Canadians, as well as others exiled from Fort Snelling. An 1837 treaty with local Native Americans secured the city for white settlement. In 1841, the settlement was named Saint-Paul by Father Lucien Galtier, a priest from France, in honor of Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

. By the early 1840s the area had become important as a trading center, a stopping point for settlers heading west, and was known regionally as Pig's Eye or Pig's Eye Landing. The Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Minnesota and the w ...

was formalized in 1849 with Saint Paul named as its capital. Saint Paul was incorporated as a city in 1854, and in 1858, Minnesota was admitted as the 32nd state of the union with Saint Paul becoming the capital.

Natural geography played a role in the settlement and development of Saint Paul as a trade and transportation center. The Mississippi River valley in the area surrounding the city is defined by numerous stone bluffs that line both sides of the river. Saint Paul developed around Lambert's Landing, the last easily accessible point to unload boats coming upriver, some downstream from Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony (), located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1800s, various dams were built ...

, the geographic feature that defined the location of Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

and its prominence as the "Mill City". This made Saint Paul a gateway to the Upper Midwest for settlers heading westbound to the Minnesota frontier or the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

. In 1858, more than 1,000 steamboats

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

unloaded cargo and passengers at Saint Paul. The Saint Anthony Trail, a cart and wagon road, led from Saint Paul to the Red River valley. The trail was followed by numerous railroads that were headquartered in Saint Paul, such as the Great Northern Railway and Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was an important American transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the Western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest between 1864 and 1970. It was approved and chartered b ...

, which are today part of the BNSF Railway

BNSF Railway is the largest freight railroad in the United States. One of six North American Class I railroads, BNSF has 36,000 employees, of track in 28 states, and over 8,000 locomotives. It has three Transcontinental railroad, transcontine ...

. For well over a hundred years, Saint Paul was a frontier town and a railroad town. By the late 20th century, the city became more influenced by commerce, as well as its role as the state capital. It has been called "The Last City of the East".

The character of the city has been defined by its people, beginning with Indigenous people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

such as the Kaposia

Kaposia or Kapozha was a seasonal and migratory Mdewakanton, Dakota settlement, also known as "Little Crow's village," once located on the east side of the Upper Mississippi River, Mississippi River in present-day Saint Paul, Minnesota. The Kapos ...

band of the Mdewakanton Dakota

The Mdewakanton or Mdewakantonwan (also spelled ''Mdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ'' and currently pronounced ''Bdewákhaŋthuŋwaŋ'') are one of the sub-tribes of the Isanti (Santee) Dakota (Sioux). Their historic home is Mille Lacs Lake (Dakota: ''Mde Wá ...

, who have for centuries called the area that is now Saint Paul their home. Throughout its history, first-generation immigrants have been a dominant force in Saint Paul, introducing their languages, religions, and cultures. The influx of peoples is illustrated by the city's institutions, built by French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, French Canadian

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French people, French colonists first arriving in Canada (New France), France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, Irish, Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

, Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

, Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

, Somali, and Hmong people

The Hmong people ( RPA: , CHV: ''Hmôngz'', Nyiakeng Puachue: , Pahawh Hmong: , , zh, c=苗族蒙人) are an indigenous group in East Asia and Southeast Asia. In China, the Hmong people are classified as a sub-group of the Miao people. Th ...

.

Geological history

During UpperCambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

and Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

time, from approximately 505 to 438 million years ago, shallow tropical seas covered much of then-equatorial southeastern Minnesota.Mossler, J. and Benson, S., 1995, 1999, 2006Fossil Collecting in the Twin Cities Area

Minnesota at a Glance: Minnesota Geological Survey: University of Minnesota. During this time, the

sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

s that constitute the bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid rock that lies under loose material ( regolith) within the crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface material. An exposed portion of bed ...

of St. Paul were deposited. The most visible of these are the to thick layer of St. Peter Sandstone, the lowest layer of sedimentary rock above the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

in Saint Paul, which is overlain by a thin— to thick—layer of Glenwood Shale, and capped by a thick layer of Platteville Limestone

The Platteville Limestone is the Ordovician limestone formation in the sedimentary sequence characteristic of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. It is characterized by its gray color, rough texture, and numerous fossils. Its type ...

. These units are overlain by the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

iferous Decorah Shale, which is in some places completely eroded and in others up to thick, and exposed at the brickyards, a popular fossil hunting location in Lilydale Park. All of the units exposed on the surface in St. Paul are of Ordovician age. Marine fossils can be seen embedded in limestone structures, such as the Henry Hastings Sibley

Henry Hastings Sibley (February 20, 1811 – February 18, 1891) was a fur trader with the American Fur Company, the first U.S. Congressional representative for Minnesota Territory, the first governor of the state of Minnesota, and a U.S. mi ...

House.

About 20,000 years ago, the area was covered by the Superior Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which left the St. Croix moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and Rock (geology), rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a gla ...

on the Twin Cities as it receded. Later the Grantsburg Sublobe of the Des Moines Lobe also covered the area. These thick layers of ice cut through the Platteville limestone cap rock Caprock or cap rock is a hard, resistant, and impermeable layer of rock that overlies and protects a reservoir of softer organic material, similar to the crust on a pie where the crust (caprock) prevents leakage of the soft filling (softer material ...

with tremendous force, forming tunnel valleys, and released glacial meltwater. The result was a series of troughs in the limestone, which were filled by glacial till and outwash deposit as the glaciers receded. Sometimes the sediment would be mixed with huge chunks of ice, which would leave voids, or kettles, in the soil. These kettles later filled with water and became Lake Como

Lake Como ( , ) also known as Lario, is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of , making it the third-largest lake in Italy, after Lake Garda and Lake Maggiore. At over deep, it is one of the deepest lakes in Europe. ...

and Lake Phalen

Lake Phalen is an urban lake located in Saint Paul, Minnesota and in its suburb of Maplewood. It is one of the largest lakes in Saint Paul and is the centerpiece of the Phalen Regional Park System. The lake drains into the Mississippi River afte ...

.

Glacial River Warren

Glacial River Warren, also known as River Warren, was a prehistoric river that drained Lake Agassiz in central North America between about 13,500 and 10,650 BP calibrated (11,700 and 9,400 14C uncalibrated) years ago. A part of the uppermost porti ...

was a prehistoric river that drained Lake Agassiz

Lake Agassiz ( ) was a large proglacial lake that existed in central North America during the late Pleistocene, fed by meltwater from the retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet at the end of the last glacial period. At its peak, the lake's area wa ...

in central North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

between 11,700 and 9,400 years ago. Lake Agassiz, which was up to 600–700 feet (~200 m) deep, and at various times covered areas totaling over 110,000 square miles (~300,000 km2), was formed from the meltwaters of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Wisconsonian glaciation of the last ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

. The enormous outflow from this lake carved a wide valley now occupied by the much smaller Minnesota River

The Minnesota River () is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles (534 km) long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa.

It rises in southwestern ...

and the Upper Mississippi River

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River upstream of St. Louis, Missouri, United States, a city at the confluence of its main tributary, the Missouri River. Historically, it may refer to the area above the Arkansa ...

below its confluence with the Minnesota. Blocked by an ice sheet to the north, the lake water rose until about 9,700 years Before Present

Before Present (BP) or "years before present (YBP)" is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because ...

(BP), when it overtopped the ''Big Stone Moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and Rock (geology), rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a gla ...

'', a ridge of glacial drift left by the receding glacier, at the location of Browns Valley, Minnesota

Browns Valley is a city in Traverse County, Minnesota, United States, adjacent to the South Dakota border. The population was 558 at the 2020 census.

Browns Valley lies along the Little Minnesota River between the northern end of Big Stone ...

. The lake's outflow was catastrophic at times, creating a wide valley to Saint Paul, where the massive River Warren Falls

The River Warren Falls was a massive waterfall on the glacial River Warren initially located in present-day Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. The waterfall was across and high.

Geologic history

The area now occupied by the Twin Cities o ...

once graced the landscape. Over 1700 years this waterfall retreated upstream and undercut the Mississippi at the site of Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint An ...

. The falls then split. The Mississippi falls migrated upstream to form Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony (), located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1800s, various dams were built ...

and create Minnehaha Falls

Minnehaha Park is a city park in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, and home to Minnehaha Falls and the lower reaches of Minnehaha Creek. Officially named Minnehaha Regional Park, it is part of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board sy ...

in Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

. The River Warren falls receded west in the Minnesota River valley until they reached an older buried river valley about two miles (3 km) west of the confluence, where the falls were extinguished. The high bluffs on either side of the river represent the channel dug by the River Warren as it carried massive volumes of water through Saint Paul.

First people

As many as 37burial mounds

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. ...

were constructed by the Hopewell culture

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from ...

, one of several Native American Mound builders approximately 2000 years ago at present-day Indian Mounds Park. The dead were buried with artifacts, indicating a religious tradition. The mounds built by the Hopewell culture were built in a distinctive fashion, burying the deceased's ashes; the Dakota people

The Dakota (pronounced , or ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe (Native American), tribe and First Nations in Canada, First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultur ...

later used the same site to bury their dead, wrapping the bodies in animal skins. The Dakota lived near the site of the mounds in the village of Kaposia

Kaposia or Kapozha was a seasonal and migratory Mdewakanton, Dakota settlement, also known as "Little Crow's village," once located on the east side of the Upper Mississippi River, Mississippi River in present-day Saint Paul, Minnesota. The Kapos ...

. Below the mounds was a large cave at the base of the bluff. Carver's Cave was called by the Dakota, "Wakan Tipi" ("sacred lodge", or "dwelling of the sacred"). Petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s of rattlesnakes and bears were cut into the sandstone walls. Following the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters, the roughly 200 Dakota living on the bluffs of Saint Paul vacated the area and moved to the west side of the Mississippi River. The land was soon colonized by French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

Voyageurs

Voyageurs (; ) were 18th- and 19th-century French and later French Canadians and others who transported furs by canoe at the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ...

who staked claims to plots on Dayton's Bluff.

Dakota people refer to the area encompassing Saint Paul as Bdóte

Bdóte ( ""; ; deprecated spelling Mdote) is a significant Dakota people, Dakota sacred landscape where the Minnesota River, Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers meet, encompassing Pike Island, Fort Snelling, Coldwater Spring, Indian Mounds Park (Sai ...

, which they considered a site of creation.

European-American settlement

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

claimed the land east of the Mississippi and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, then Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, and again France claimed the land west of the river as further territory of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

. In 1787 land on the east side of the river became part of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

. Between the 1780s and 1800s, Spanish traders from St. Louis traded through the region, including Manuel Lisa and José María Vigó (also known as Francisco Vigó). From 1837 to 1848, Saint Paul grew from a few traders of mostly French and French Canadian origins, with tents and shacks on the riverside to a small town with settlers starting to put down roots; in 1840, the town had only nine cabins scattered between the Upper and Lower Landings. Some were members of the failed Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

in Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

, but they were soon joined by first-generation American pioneer

American pioneers, also known as American settlers, were European American,Asian American, and African American settlers who migrated westward from the British Thirteen Colonies and later the United States of America to settle and develop areas ...

s. No structures in Saint Paul have survived from this period. In 1841, Father Lucien Galtier

Lucien Galtier ( – February 21, 1866) was a French Catholic priest. He was the first Catholic priest to serve in Minnesota. He was born in southern France in the town of Saint-Affrique, department of Aveyron. The year of his birth is somewhat u ...

established a Catholic chapel, Saint Paul's Chapel, on the bluffs above the landing (near present-day Second Street and Cedar Street), naming it in honor of his favorite saint and because of the pairing with Saint Peter's Church in Mendota, upstream and across the river. While it is said that the area had up until that point been referred to as "Pig's Eye" (''French'': L'Oeil du Cochon) or "Pig's Eye Landing" after the tavern of settler Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, the landing by the chapel gradually became named known as "Saint Paul's Landing" through this the name of the chapel gradually was applied to the entire settlement. The name Saint Paul was then first used in official records at the marriage of Vetel and Adele Guerin on January 26, 1841. In 1847, the Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

school teacher, Harriet Bishop

Harriet E. Bishop (January 1, 1817 – August 8, 1883) was an American educator, writer, suffragist, and temperance activist. Born in Panton, Vermont, she moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota in 1847. There, she started the first public school as w ...

came from Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

(via New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

) and opened the city's first school in a cabin at St. Peter Street and Kellogg Boulevard. There she taught children of diverse ethnic, racial, and religious backgrounds and supported the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting Temperance (virtue), temperance or total abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and ...

. Harriet Island was named for her. In 1849, the Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Minnesota and the w ...

was formalized and Saint Paul was named as its capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

. Justus Ramsey's older brother, Alexander Ramsey

Alexander Ramsey (September 8, 1815 April 22, 1903) was an American politician, who became the first Minnesota Territorial Governor and later became a U.S. Senator. He served as a Whig and Republican over a variety of offices between the 18 ...

, a Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

politician moved there to become the first territorial governor. In 1850, the city narrowly survived a proposed law to move the capital to Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

when territorial legislator, Joe Rolette

Joseph Rolette, Jr. (23 October 1820 – 16 May 1871) was an American fur trader and politician during Minnesota's territorial era and the Civil War. His father was Jean Joseph Rolette, often referred to as Joe Rolette the Elder, a French ...

disappeared with the approved bill.

Early boom years, 1849–1860

In the decade following its designation as the territorial capital, Saint Paul grew exponentially from 900 in 1849 to 10,000 in 1860. William Williams described this boom town during a visit on June 14, 1849:

In the decade following its designation as the territorial capital, Saint Paul grew exponentially from 900 in 1849 to 10,000 in 1860. William Williams described this boom town during a visit on June 14, 1849:

"awoke early, found out Boat landed at St. Paul's discharging flour. I took a walk up the steep bluff and took a view of the town generally. The Upper or new town is laid out on a wild looking place situated on high bluffs which have a steep face to the River & Rocks projecting. The lower, or Old French town, is composed of about 10 or 15 houses, some of them bark roofs. In this part is found Half breed Indians & French and Canadian French. This part stands on a lower ground just above a ravine where Carver’s Cave is. Site of upper town is more broken and it stands on a succession of benches of sand. There is a great many of people here. Many of them have for a covering their wagons and tents. There is two large frame hotels going up and a great many small frame building scattered among the bushes, for the greater part of the ground where the new town stands is not yet grubbed out, full of hazel bushes and scrub oaks. They area asking as high as $500 for lots. I think they will have a great deal of work to do here before they will have things as they should be. There is a slough 100 yards wide between the town and the river, over which they build a causeway to get from the River to the town. Between the river and the slough there is barely room for three or four warehouses. Two are here erecting."

Minnesota's first newspaper, the ''Minnesota Pioneer'', the forerunner of today's ''

Minnesota's first newspaper, the ''Minnesota Pioneer'', the forerunner of today's ''St. Paul Pioneer Press

The ''St. Paul Pioneer Press'' is a newspaper based in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. It serves the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropolitan area. Circulation is heaviest in the east metro, including Ramsey, Dakota, and Washington countie ...

'', was established by James M. Goodhue in 1849. Just west of downtown Saint Paul is the neighborhood of Irvine Park; it was plat

In the United States, a plat ( or ) (plan) is a cadastral map, drawn to scale, showing the divisions of a piece of land. United States General Land Office surveyors drafted township plats of Public Lands Survey System, Public Lands Surveys to ...

ted by John Irvine and Henry Mower Rice

Henry Mower Rice (November 29, 1816January 15, 1894) was a fur trader and an American politician prominent in the statehood of Minnesota.

Early life

Henry Rice was born on November 29, 1816, in Waitsfield, Vermont to Edmund Rice and Ellen (Dur ...

in 1849, and Saint Paul's oldest house, the Charles Symonds House (1850) is located there. Other surviving homes from this period include the Justus Ramsey Stone House (1851), the Benjamin Brunson House (1856), the William Dahl House (1858), the David Luckert House (1858), and the Johan and Maria Magdalena Schilliger House (1859–1862). By mid-decade, a primitive capitol, a courthouse (a Greek Revival

Greek Revival architecture is a architectural style, style that began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe, the United States, and Canada, ...

building designed by David Day), and a small prison had been built. The first bridge to cross the Mississippi River in Saint Paul was the Wabasha Street Bridge

The Wabasha Street Bridge is a segmental bridge that spans the Mississippi River in downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. It was named Wabasha Street Freedom Bridge in 2002, to commemorate the first anniversary of the September 11 attac ...

, a wooden Howe Truss bridge completed in 1859. Saint Paul saw early population growth from many regions and different ethnic groups. However, a principal factor in early population growth of Saint Paul was the Quebec diaspora of the 1840s-1930s, in which one million French Canadians moved to the United States, principally to the New England states, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. As the population grew, so too did religious and cultural institutions. German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

-Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

pioneers formed Saint Paul's first synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

in 1856 and the German cultural society, ''Leseverein'' built ''Athenaeum'', a ''Deutsches Haus'' for theatrical productions. In the early 1850s, the city's one Catholic parish was divided into three factions; the French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, and Irish groups each held service in their native tongues in one building. By 1856, the Diocese allowed the German Catholics to have their own parish, and the first Assumption Church was built. In 1853, the Baldwin School and in 1854, the College of Saint Paul were founded by a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

minister; these were to later combine to become Macalester College

Macalester College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. Founded in 1874, Macalester is exclusively an undergraduate institution with an enrollment of 2,142 students in the fall of 2023. The college ha ...

. The city's musical traditions began with informal concerts in homes; piano

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an Action (music), action mechanism where hammers strike String (music), strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a c ...

s and melodeon

Melodeon may refer to:

*Melodeon (accordion), a type of button accordion

*Melodeon (organ)

The pump organ or reed organ is a type of organ that uses free reed aerophone, free reeds to generate sound, with air passing over vibrating thin metal ...

s were brought up the river by steamship. No longer cut off from the outside world, the first telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

line reached Saint Paul in 1860.

Full steam growth

As Saint Paul grew, and its close neighbors, Saint Anthony and Minneapolis grew with even greater precipitancy, the docks at "Lower Landing" and "Upper Landing" bustled with activity. The state's population reached 200,000 by 1860, and most of those had arrived by

As Saint Paul grew, and its close neighbors, Saint Anthony and Minneapolis grew with even greater precipitancy, the docks at "Lower Landing" and "Upper Landing" bustled with activity. The state's population reached 200,000 by 1860, and most of those had arrived by riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury ...

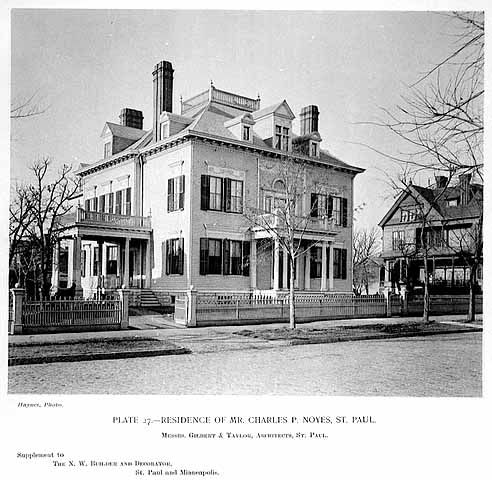

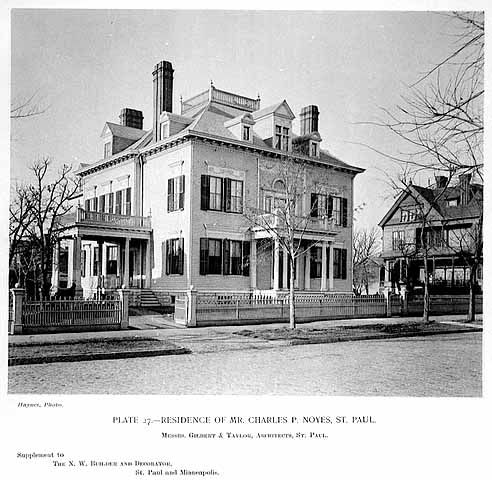

, disembarking in Saint Paul. Farms were staked out in the vast countryside, including the Davern Farm (1862) and the Spangenberg Farm (1864). Wealthy businessmen such as James C. Burbank, the owner of the Minnesota Stage Company, which held a statewide monopoly controlling of stage-lines by 1865, started to spend their fortunes building grand estates. Burbank's Home (1862–1865) was one of the first mansions to be built high on the bluffs on Summit Avenue. By the end of the 19th century, his was only one of hundreds of impressive edifices in the Historic Hill District, the West Summit Avenue Historic District, the Woodland Park District, Dayton's Bluff, and the Irvine Park Historic District

Irvine Park is a neighborhood just west of downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States, that contains a number of historic homes. The neighborhood was platted by John Irvine and Henry Mower Rice in 1849. At the center of the neighborhood ...

, where the powerful and wealthy resided.

On the east side, new immigrants from Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

with little wealth and few English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

skills settled in the ravine of Phalen's Creek, or Swede Hollow

Swede Hollow was a neighborhood of Saint Paul, Minnesota. It was one of a large group of neighborhoods collectively known as the East Side, lying just to the east of the near-downtown Railroad Island neighborhood, and at the northwestern base ...

. The creek, named for Edward Phelan runs from Lake Phalen

Lake Phalen is an urban lake located in Saint Paul, Minnesota and in its suburb of Maplewood. It is one of the largest lakes in Saint Paul and is the centerpiece of the Phalen Regional Park System. The lake drains into the Mississippi River afte ...

to the Mississippi. Many lived in shanties in the creek valley, which served as an open sewer; the creek also provided water power for industries such as Excelsior Brewery (later Hamm's Brewery

Theodore Hamm's Brewing Company was an American brewing company established in 1865 in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Becoming the fifth largest brewery in the United States, Hamm's expanded with additional breweries that were acquired in other cities, ...

). A similar community just downstream called Connemara Patch also existed for Irish immigrants.

True to history, the downtown area was home to several well-known brothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

s; the first was known to have opened in 1868, providing employment for some women in the untamed frontier town. One stylish madam, Mary Robinson reported property worth $77,000 in 1870. Others were not so fortunate. Kate Hutton was shot and killed by a lover, and presumably other ladies of the night were victims of violence; Henrietta Charles died of syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

at age 38. In 1872 Horace Cleveland

Horace William Shaler Cleveland (December 16, 1814 – December 5, 1900) was an American landscape architect. His approach to natural landscape design can be seen in projects such as the Grand Rounds in Minneapolis; Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Conc ...

visited the city and proposed a citywide park system; shortly thereafter Lake Como

Lake Como ( , ) also known as Lario, is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of , making it the third-largest lake in Italy, after Lake Garda and Lake Maggiore. At over deep, it is one of the deepest lakes in Europe. ...

was purchased, eventually to be the anchor of Como Park, Zoo, and Conservatory

The Como Park Zoo and Marjorie McNeely Conservatory (or just Como Zoo and Conservatory) are located in Como Park at 1225 Estabrook Drive, Saint Paul, Minnesota. The park, zoo and conservatory are owned by the City of Saint Paul and are a divisi ...

. Later, in 1899, Lake Phalen

Lake Phalen is an urban lake located in Saint Paul, Minnesota and in its suburb of Maplewood. It is one of the largest lakes in Saint Paul and is the centerpiece of the Phalen Regional Park System. The lake drains into the Mississippi River afte ...

was also purchased by the city.

By 1877, the volunteer fire department was disbanded in favor of a paid department. The volunteers had served the city since 1854, but the building boom necessitated moving to a full-time department. Horse-drawn street cars and even a few cable cars covered of city streets by 1880, but by 1891 they were all replaced by electric streetcar lines. The outlying neighborhoods grew out of the placement of the streetcar lines and short lines, Merriam Park in 1882, Macalester Park in 1883, Saint Anthony Park in 1885, and Groveland in 1890. In 1885 a New York reporter wrote that Saint Paul was "another Siberia, unfit for human habitation" in winter. Offended by this attack on their Capital City, the Saint Paul Chamber of Commerce decided to not only prove that Saint Paul was habitable but that its citizens were very much alive during winter, the most dominant season. Thus was born the

By 1877, the volunteer fire department was disbanded in favor of a paid department. The volunteers had served the city since 1854, but the building boom necessitated moving to a full-time department. Horse-drawn street cars and even a few cable cars covered of city streets by 1880, but by 1891 they were all replaced by electric streetcar lines. The outlying neighborhoods grew out of the placement of the streetcar lines and short lines, Merriam Park in 1882, Macalester Park in 1883, Saint Anthony Park in 1885, and Groveland in 1890. In 1885 a New York reporter wrote that Saint Paul was "another Siberia, unfit for human habitation" in winter. Offended by this attack on their Capital City, the Saint Paul Chamber of Commerce decided to not only prove that Saint Paul was habitable but that its citizens were very much alive during winter, the most dominant season. Thus was born the Saint Paul Winter Carnival

The Saint Paul Winter Carnival is an annual festival in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States.

History

In 1885, a New York reporter wrote that Saint Paul was, "another Siberia, unfit for human habitation" in winter. Offended by this attack on th ...

. In 1886 King Boreas the First was crowned and the first Winter Carnival commenced. This festival also featured an ice castle, an elaborate creation made from the ice of Minnesota lakes, which has evolved into an internationally recognized icon for Saint Paul's festival. Foreign-language newspapers flourished, with local publications in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, Norwegian, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, Danish, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

, and Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

. African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

s read ''The Appeal'' and Jewish immigrants read the ''Jewish Weekly''.

Convenient transportation and an increasingly dense population contributed to an outbreak of

Convenient transportation and an increasingly dense population contributed to an outbreak of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

in 1898. Soldiers mustering for the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

were encouraged by 40,000 visitors and 500 soldiers took ill from the exposure. By the turn of the century, resentment of the newest immigrants began to take hold. Henry A. Castle wrote that the earliest immigrants, primarily from the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

easily reached the standards expected of them. In contrast, by the 1880s, most new immigrants were unskilled workers from southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

, eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. He described them as illiterate, unable to be assimilated into the city's culture, and often without families. He said they drained the economy by working here and sending money back to their homelands.

Saint Paul's historic Landmark Center, was built in 1902 and originally served as the Federal Court House and Post Office for the Upper Midwest. It stands like a time capsule in beautiful Rice Park. This building is now an arts and culture center for Saint Paul. As a courthouse, John Dillinger

John Herbert Dillinger (; June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster during the Great Depression. He commanded the Dillinger Gang, which was accused of robbing twenty-four banks and four police stations. Dillinger was imprison ...

, Machine Gun Kelly, and Baby Face Nelson

Lester Joseph Gillis (December 6, 1908 – November 27, 1934), also known as George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson, was an American bank robber who became a criminal partner of John Dillinger when he helped Dillinger escape from prison in Crown P ...

were tried in the building.

The state capitol

Much of Saint Paul's vibrancy can be attributed to its status as the seat of state government. Capitol buildings were built in 1854 and 1882. But by the turn of the century, the third state capitol was under construction. The building was designed byCass Gilbert

Cass Gilbert (November 24, 1859 – May 17, 1934) was an American architect. An early proponent of Early skyscrapers, skyscrapers, his works include the Woolworth Building, the United States Supreme Court building, the state capitols of Minneso ...

and modeled after Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian Renaissance architecture, Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the cit ...

in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

—the unsupported marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

is the second largest in the world, after Saint Peter's. At a cost of USD

The United States dollar (symbol: $; currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it int ...

$4.5 million, it opened in 1905. The exterior is made of Georgian marble and Saint Cloud granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

. The interior walls are constructed of 20 different types of stone, including Mankato

Mankato ( ) is a city in Blue Earth, Nicollet, and Le Sueur counties in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It is the county seat of Blue Earth County, Minnesota. The population was 44,488 at the 2020 census, making it the 21st-largest city in Mi ...

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

. Above the southern (main) entrance to the building is a gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

quadriga

A quadriga is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in classical antiquity and the Roman Empire. The word derives from the Latin , a contraction of , from ': four, and ': yoke. In Latin the word is almos ...

called the '' Progress of the State'' which was sculpted by Daniel Chester French

Daniel Chester French (April 20, 1850 – October 7, 1931) was an American sculpture, sculptor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His works include ''The Minute Man'', an 1874 statue in Concord, Massachusetts, and his Statue of Abr ...

and Edward Clark Potter

Edward Clark Potter (November 26, 1857 – June 21, 1923) was an American sculptor best known for his equestrian and animal statues. His most famous works are the marble lions, nicknamed ''Patience'' and ''Fortitude'', in front of the New York ...

. It was completed and raised to the roof of the capitol in 1906. On the floor of the rotunda

A rotunda () is any roofed building with a circular ground plan, and sometimes covered by a dome. It may also refer to a round room within a building (an example being the one below the dome of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.). ...

under the dome is a large star, representing the "North Star State." Above is a crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

chandelier. Art-work and gold-leaf are used liberally to decorate the legislative structure. The building's opulence is testimony to the great wealth the state generated at that time.

Commerce and industry

As

As Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

boomed as a mill

Mill may refer to:

Science and technology

* Factory

* Mill (grinding)

* Milling (machining)

* Millwork

* Paper mill

* Steel mill, a factory for the manufacture of steel

* Sugarcane mill

* Textile mill

* List of types of mill

* Mill, the arithmetic ...

ing city, Saint Paul flourished in financing and commerce. Brewers Anthony Yoerg and Theodore Hamm arrived with their German recipes for beer and found a thirsty population here. Bohn Manufacturing Company, a cabinet-maker, rode the wave as households replaced their ice box

An icebox (also called a cold closet) is a compact non-mechanical refrigerator which was a common early-twentieth-century kitchen appliance before the development of safely powered refrigeration devices. Before the development of electric refrig ...

es with refrigerators, becoming Seeger Refrigerator Company, eventually to be bought out by Whirlpool Corporation

Whirlpool Corporation is an American multinational corporation, multinational manufacturer and marketer of home appliances headquartered in Benton Charter Township, Michigan, United States. In 2023, the Fortune 500 company had an annual revenue ...

. In 1906 the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company moved from Duluth

Duluth ( ) is a Port, port city in the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of St. Louis County, Minnesota, St. Louis County. Located on Lake Superior in Minnesota's Arrowhead Region, the city is a hub for cargo shipping. The population ...

to Saint Paul, later to become 3M, a Fortune 500

The ''Fortune'' 500 is an annual list compiled and published by ''Fortune (magazine), Fortune'' magazine that ranks 500 of the largest United States Joint-stock company#Closely held corporations and publicly traded corporations, corporations by ...

company. Banks financed railroads, mills, and housing for the booming economy and burgeoning population. Grand buildings such as the Germania Bank Building (1889), the Manhattan Building (1889), the Merchants National Bank (1892), and Pioneer and Endicott Buildings

The Pioneer and Endicott Buildings are two adjoining office and apartment buildings located between downtown and Lowertown Saint Paul, Minnesota. The 1890-built Endicott building forms an L-shape around the 1889-built Pioneer Building. The Endicot ...

(1889–1890) soared in Lowertown, where arriving businessmen and new immigrants couldn't help but be impressed by them. Blocks of Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

storefronts with upper-level apartments sprouted along the city streets. Some surviving ones include the Schornstein Grocery and Saloon (1884), the Walsh Building (1888), the Rochat-Louise-Sauerwein Block (1885–1895), and the Otto W. Rohland Building (1891). With wealth and leisure time, cultural institutions emerged, such as the Shubert Theatre now Fitzgerald Theater. Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

funded three libraries in the city: the Saint Anthony Park, Riverview, and Arlington Hills libraries, while James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railway director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest ...

endowed the Saint Paul Public Library

The Saint Paul Public Library is a library system serving the residents of Saint Paul, Minnesota, in the United States. The library system includes a Central Library, twelve branch locations, and a bookmobile. It is a member of the Metropolitan ...

/ James J. Hill Reference Library. In 1924 the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

opened the Twin Cities Assembly Plant

The Twin Cities Assembly Plant was a Ford Motor Company manufacturing facility in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States, that operated from 1925 to 2011. In 1912, Ford's first assembly and sales activities in Minnesota began in a former warehouse i ...

; the site is located on the Mississippi River adjacent to a company-owned dam, which generates hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

. Somewhat unique to this site are the sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

tunnels beneath the factory. Ford mined silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

to make glass for the automobiles produced here, leaving an extensive tunnel system deep into the river-side bluffs. The plant was converted to produce armored vehicles during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Higher education

Higher education has played a prominent part in the city's history.Hamline University

Hamline University ( ) is a private university in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. Founded in 1854, Hamline is the oldest university in Minnesota, the first coeducational university in the state, and is one of five Associated Colleges of th ...

(1854) Hamline was founded and named after Methodist Bishop Leonidas Lent Hamline, who provided USD

The United States dollar (symbol: $; currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it int ...

$25,000 of his own money to launch the school. The university opened in Red Wing, Minnesota

Red Wing is a city in and the county seat of Goodhue County, Minnesota, United States, along the upper Mississippi River. The population was 16,547 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is part of the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metropo ...

, with the premise that the school would eventually move to Saint Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world. For his contributions towards the New Testament, he is generally ...

. A statue of the bishop, sculpted by the late professor of art Michael Price, stands on campus. In 1869, the university shut down its operations after enrollment dropped drastically due to the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. The first building at the Red Wing site was torn down in 1872. A new building opened in 1880 in Saint Paul's Midway neighborhood housing 113 students. The building burned in 1883, and the following year, a new building was developed: Old Main, Hamline's oldest remaining building.

In 1917 Hamline actively responded to the call of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

by incorporating an Army Training Corps at the university. More buildings developed after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. By 1928, Hamline consisted of Old Main (classrooms and administration), Manor House (women's residence hall), a Methodist church, and Goheen Hall (men's residence hall). Hamline faced tough challenges during the U.S. economic depression of the early 1930s. After World War II, Hamline's choir and theater department became a musical reference in Minnesota. The choir would eventually become nationally renowned, and would travel overseas. By 1950, enrollment surpassed 1000 students, and the board of directors decided on further development. New developments included two new residential halls (Sorin and Drew halls), a cultural center (Bush Student Center), a new carpentry center (VanHemert Hall) a new arts center, and a new science center (Drew Hall of Science). All of these projects were completed in the mid-1960s.

Macalester College

Macalester College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. Founded in 1874, Macalester is exclusively an undergraduate institution with an enrollment of 2,142 students in the fall of 2023. The college ha ...

(1885) had its beginnings due to the efforts of the Reverend Dr. Edward Duffield Neill

Edward Duffield Neill (1823 – 1893) was an American author and educator.

Neill was born in Philadelphia. After studying at the University of Pennsylvania for some time, he enrolled at Amherst College and graduated from Amherst in 1842, then s ...

, who had founded two schools in Saint Paul and nearby Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

which were named after M.W. Baldwin, a locomotive

A locomotive is a rail transport, rail vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. Traditionally, locomotives pulled trains from the front. However, Push–pull train, push–pull operation has become common, and in the pursuit for ...

builder and friend of Neill's. With the intention of turning his Saint Paul Baldwin School into a college, Neill turned to Charles Macalester, a businessman from Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, for sponsorship. Macalester donated a building near Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony (), located at the northeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Mississippi River. Throughout the mid-to-late 1800s, various dams were built ...

, and the college was chartered in 1874. The college moved to its present location in 1885 after building an endowment and seeking the help of the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Christianity, Reformed Protestantism, Protestant tradition named for its form of ecclesiastical polity, church government by representative assemblies of Presbyterian polity#Elder, elders, known as ...

. The College first admitted women in 1893, and despite being affiliated with a religious institution, remained open to students of other faiths.

Macalester was largely carried through financial hardship and brought to prominence by Dr. James Wallace, father of DeWitt Wallace

William Roy DeWitt Wallace ( ; November 12, 1889 – March 30, 1981), publishing as DeWitt Wallace, was an American magazine publisher.

Wallace co-founded ''Reader's Digest'' with his wife Lila Bell Wallace, publishing the first issue in 1922.

...

. Wallace was acting president of the college from 1894 to 1900, president from 1900 to 1906, and professor until just before his death in 1939. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the college developed a reputation for internationalism

Internationalism may refer to: