The history of independent India or history of Republic of India began when the country became an

independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

sovereign state within the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

on 15 August 1947. Direct administration by the British, which began in 1858, affected a political and economic unification of the

subcontinent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as in the case of A ...

. When British rule came to an end in 1947, the subcontinent was partitioned along religious lines into two separate countries—India, with a majority of

Hindus

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

, and Pakistan, with a majority of

Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

. Concurrently the Muslim-majority northwest and east of

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

was separated into the

Dominion of Pakistan

The Dominion of Pakistan, officially Pakistan, was an independent federal dominion in the British Commonwealth of Nations, which existed from 14 August 1947 to Pakistan Day, 23 March 1956. It was created by the passing of the Indian Independence ...

, by the

Partition of India

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Dominion of India, Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. The Union of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Paki ...

. The partition led to a

population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but they also occur d ...

of more than 10 million people between India and Pakistan and the death of about one million people.

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

leader

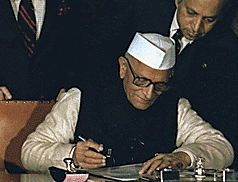

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

became the first

Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen Union Council of Ministers, Council of Ministers, despite the president of ...

, but the leader most associated with the

independence struggle,

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

, accepted no office. The

constitution adopted in 1950 made India a democratic republic with

Westminster style parliamentary system of government, both at federal and state level respectively. The democracy has been sustained since then. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newly independent states.

The country has faced

religious violence

Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the target or perpetrator of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war and also nonviolence and peacemaking. ...

,

naxalism,

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

and regional

separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

insurgencies. India has unresolved territorial disputes with China which escalated into a war in

1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

and

1967

Events January

* January 1 – Canada begins a year-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, Confederation, featuring the Expo 67 World's Fair.

* January 6 – Vietnam War: United States Marine Corps and Army of ...

, and with

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

which resulted in wars in

1947–1948,

1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The First Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is Second inauguration of Lynd ...

,

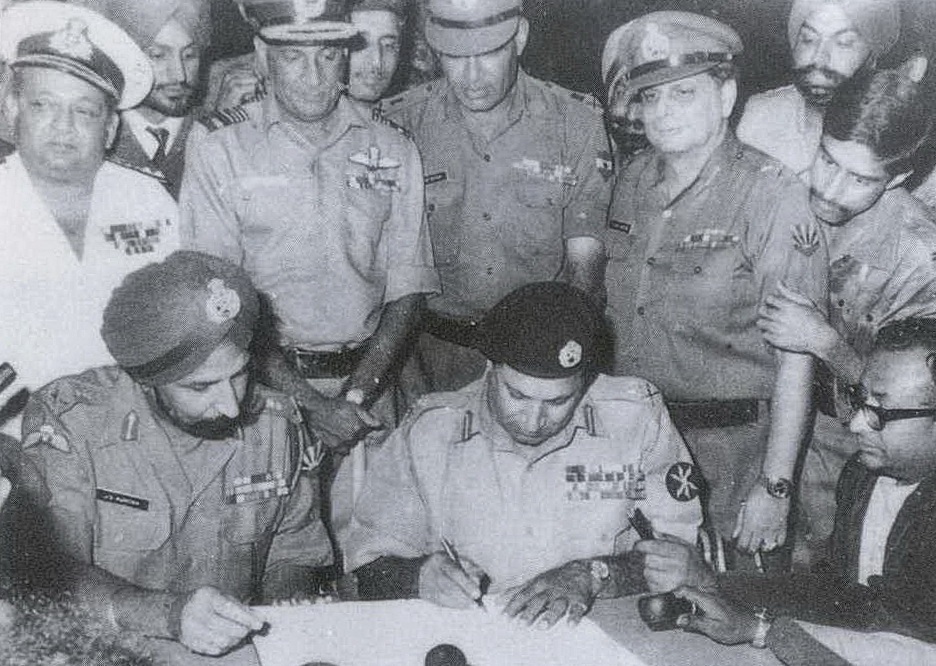

1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses (Solar eclipse of February 25, 1971, February 25, Solar eclipse of July 22, 1971, July 22 and Solar eclipse of August 20, 1971, August 20) and two total lunar eclipses (February 1971 lunar eclip ...

and

1999

1999 was designated as the International Year of Older Persons.

Events January

* January 1 – The euro currency is established and the European Central Bank assumes its full powers.

* January 3 – The Mars Polar Lander is launc ...

. India was neutral in the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, and was a leader in the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

. However, it

made a loose alliance with the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

from 1971, when Pakistan was allied with the United States and the People's Republic of China.

India is

a nuclear-weapon state, having conducted its first

nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to signal strength. Bec ...

in 1974, followed by

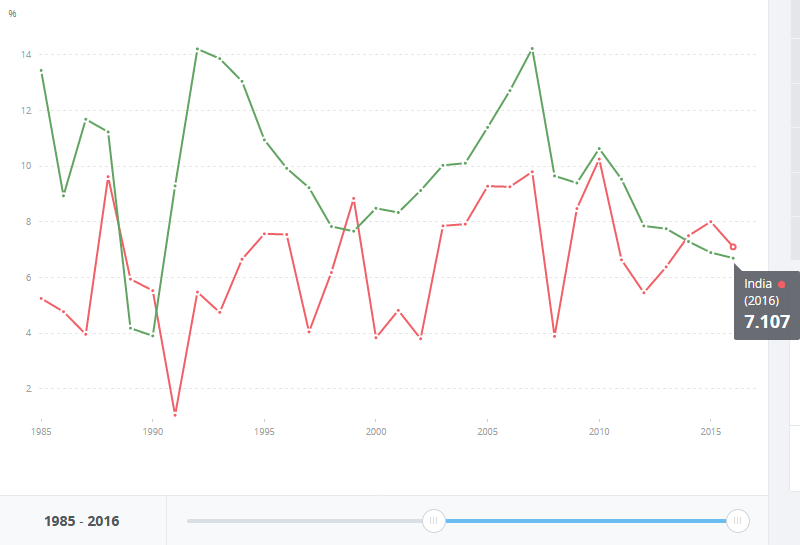

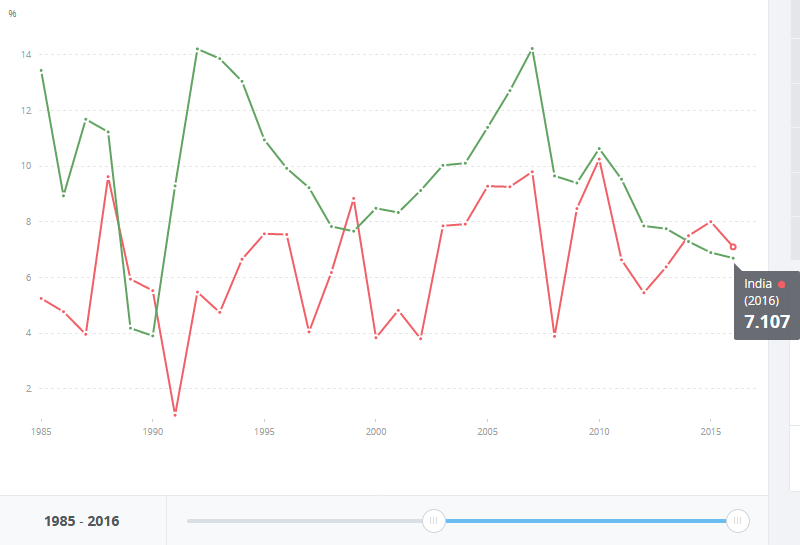

another five tests in 1998. From the 1950s to the 1980s, India followed

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

-inspired policies. The economy was influenced by

extensive regulation,

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

and public ownership, leading to pervasive

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

and slow economic growth. Since 1991,

India has pursued more economic liberalisation. Today, India is the

third largest and one of the

fastest-growing economies in the world.

From being a relatively struggling country in its formative years,

the Republic of India has emerged as a fast growing

G20

The G20 or Group of 20 is an intergovernmental forum comprising 19 sovereign countries, the European Union (EU), and the African Union (AU). It works to address major issues related to the global economy, such as international financial stabil ...

major economy.

India has sometimes been referred to as a

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

and a

potential superpower

A potential superpower is a sovereign state or other polity that is speculated to be or have the potential to become a superpower; a sovereign state or supranational union that holds a dominant position characterized by the ability to exert inf ...

given its large and growing economy, military and population.

1947–1950: Dominion of India

Independent India's first years were marked with turbulent events—a massive exchange of population with Pakistan, the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 and the integration of over 500

princely states to form a united nation.

Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ''Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel''; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime ...

,

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

and

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

also ensured that the constitution of independent India would be secular.

Partition of India

The partition of India was outlined in the

Indian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 6. c. 30) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 July 194 ...

. It led to the dissolution of the

British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

in

South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

and the creation of two independent

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s:

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

.

The change of political borders notably included the division of two provinces of

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

,

Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

and

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

. The majority

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

districts in these provinces were awarded to Pakistan and the majority non-Muslim to India. The other assets that were divided included the

British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

, the

Royal Indian Navy

The Royal Indian Navy (RIN) was the naval force of British Raj, British India and the Dominion of India. Along with the Presidency armies, later the British Indian Army, Indian Army, and from 1932 the Royal Indian Air Force, it was one of the ...

, the

Royal Indian Air Force

The Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) was the aerial force of British Raj, British India and later the Dominion of India. Along with the British Indian Army, and the Royal Indian Navy, it was one of the Armed Forces of British Indian Empire.

The ...

, the

Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British Raj, British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 3 ...

, the

railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

, and the central treasury. Self-governing independent Pakistan and India legally came into existence at midnight on 14 and 15 August 1947 respectively.

The partition caused large-scale loss of life and an unprecedented migration between the two dominions.

Among refugees who survived, it solidified the belief that safety lay among co-religionists. In the instance of Pakistan, it made palpable a hitherto only-imagined refuge for the Muslims of British India.

The migrations took place hastily and with little warning. It is thought that between 14 million and 18 million people moved, and perhaps more.

Excess mortality

In epidemiology, the excess deaths or excess mortality is a measure of the increase in the number of deaths during a time period and/or in a certain group, as compared to the expected value or statistical trend during a reference period (typicall ...

during the period of the partition is usually estimated to have been around one million.

The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that affects

their relationship to this day.

An estimated 3.5 million

[Pakistan](_blank)

Encarta

31 October 2009. Hindus

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

and

Sikhs

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Sikh'' ...

living in

West Punjab

West Punjab (; ) was a province in the Dominion of Pakistan from 1947 to 1955. It was established from the western-half of British Punjab, following the independence of Pakistan. The province covered an area of 159,344 km sq (61523 sq mi), i ...

,

North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ) was a province of British India from 1901 to 1947, of the Dominion of Pakistan from 1947 to 1955, and of the Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Pakistan from 1970 to 2010. It was established on 9 November ...

,

Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; , ), also spelled as Baluchistan or Baluchestan, is a historical region in West and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. This arid region of de ...

,

East Bengal

East Bengal (; ''Purbô Bangla/Purbôbongo'') was the eastern province of the Dominion of Pakistan, which covered the territory of modern-day Bangladesh. It consisted of the eastern portion of the Bengal region, and existed from 1947 until 195 ...

and

Sind

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind or Scinde) is a province of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest provin ...

migrated to India in fear of domination and suppression in Muslim Pakistan. Communal violence killed an estimated one million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and gravely destabilised both dominions along their

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

and

Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

boundaries, and the cities of

Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, Delhi and

Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

. The violence was stopped by early September owing to the co-operative efforts of both Indian and Pakistani leaders, and especially due to the efforts of

Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

, the leader of the Indian freedom struggle, who undertook a ''fast-unto-death'' in Calcutta and later in Delhi to calm people and emphasise peace despite the threat to his life. Both governments constructed large relief camps for incoming and leaving refugees, and the

Indian Army

The Indian Army (IA) (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the Land warfare, land-based branch and largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head ...

was mobilised to provide humanitarian assistance on a massive scale.

The

assassination of Mohandas Gandhi on 30 January 1948 was carried out by

Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) () was an Indian Hindu nationalist and political activist who was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith praye ...

, who held him responsible for partition and charged that Mohandas Gandhi was appeasing Muslims. More than one million people flooded the streets of Delhi to follow the procession to cremation grounds and pay their last respects.

In 1949, India recorded almost 1 million Hindu refugees into

West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

and other states from

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

, owing to communal violence, intimidation, and repression from Muslim authorities. The plight of the refugees outraged Hindus and Indian nationalists, and the refugee population drained the resources of Indian states, who were unable to absorb them. While not ruling out war, Prime Minister Nehru and Sardar Patel invited

Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan (1 October 189516 October 1951) was a Pakistani lawyer, politician and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan (, Roman Urdu, romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the he ...

for talks in Delhi. Although many Indians termed this

appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

, Nehru signed a pact with Liaquat Ali Khan that pledged both nations to the protection of minorities and creation of minority commissions. Although opposed to the principle, Patel decided to back this pact for the sake of peace, and played a critical role in garnering support from West Bengal and across India, and enforcing the provisions of the pact. Khan and Nehru also signed a trade agreement, and committed to resolving bilateral disputes through peaceful means. Steadily, hundreds of thousands of Hindus returned to East Pakistan, but the thaw in relations did not last long, primarily owing to the Kashmir dispute.

Integration of princely states

In July 1946,

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.

In January 1947, Nehru said that independent India would not accept the

divine right of kings. In May 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

would be treated as an enemy state.

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

consisted of 17 provinces, which existed alongside 565

princely states. The provinces were given to India or Pakistan, in two particular cases—

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

and

Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

—after being partitioned. The princes of the princely states, however, were given the right to either remain independent or accede to either dominion. Thus India's leaders were faced with the prospect of inheriting a fragmented country with independent states and kingdoms dispersed across the mainland. Under the leadership of

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ''Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel''; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime ...

, the new Government of India employed political negotiations backed with the option (and, on several occasions, the use) of military action to ensure the primacy of the central government and of the Constitution then being drafted. Sardar Patel and

V. P. Menon

Vappala Pangunni Menon (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel. By appointment from Viceroy and Governor-Genera ...

convinced the rulers of princely states contiguous to India to accede to India. Many rights and privileges of the rulers of the princely states, especially their personal estates and privy purses, were guaranteed to convince them to accede. Some of them were made

Rajpramukh

Rajpramukh was an administrative title in India which existed from India's independence in 1947 until 1956. Rajpramukhs were the appointed governors of certain Indian provinces and states.

Background

The British Indian Empire, which incl ...

(governor) and Uprajpramukh (deputy governor) of the merged states. Many small princely states were merged to form viable administrative states such as

Saurashra,

PEPSU,

Vindhya Pradesh

Vindhya Pradesh was a former state of India. It was created in 1948 as Union of Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand States from the territories of the princely states in the eastern portion of the former Central India Agency. It was named as Vindhya P ...

and

Madhya Bharat

Madhya Bharat, also known as Malwa Union, was an Indian state in west-central India, created on 28 May 1948 from twenty-five princely states which until 1947 had been part of the Central India Agency, with Jiwajirao Scindia as its Rajpramuk ...

. Some princely states such as

Tripura

Tripura () is a States and union territories of India, state in northeastern India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a populat ...

and

Manipur

Manipur () is a state in northeastern India with Imphal as its capital. It borders the Indian states of Assam to the west, Mizoram to the south, and Nagaland to the north and shares the international border with Myanmar, specifically t ...

acceded later in 1949.

There were three states that proved more difficult to integrate than others:

#

Junagadh

Junagadh () is the city and headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state. It i ...

(Hindu-majority state with a Muslim Nawab)—a December 1947

plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

resulted in a 99% vote

to merge with India, annulling the controversial accession to Pakistan, which was made by the

Nawab

Nawab is a royal title indicating a ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the Western title of Prince. The relationship of a Nawab to the Emperor of India has been compared to that of the Kingdom of Saxony, Kings of ...

against the wishes of the people of the state who were overwhelmingly

Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

and despite Junagadh not being contiguous with Pakistan.

#

Hyderabad

Hyderabad is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part of Southern India. With an average altitude of , much ...

(Hindu-majority state with a Muslim nizam)—Patel ordered the Indian army to depose the government of the

Nizam

Nizam of Hyderabad was the title of the ruler of Hyderabad State ( part of the Indian state of Telangana, and the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka). ''Nizam'' is a shortened form of (; ), and was the title bestowed upon Asaf Jah I ...

, code-named

Operation Polo

The Annexation of Hyderabad (code-named Operation Polo) was a military operation launched in September 1948 that resulted in the annexation of the princely state of Hyderabad by India, which was dubbed a "police action".

At the time of part ...

, after the failure of negotiations, which was done between 13 and 29 September 1948. It was incorporated as a state of India the next year.

# The state of

Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory since 2019

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered by India as a state from 1952 to 2019

* Jammu and Kashmir (prin ...

(a Muslim-majority state with a Hindu king) in the far north of the subcontinent quickly became a source of controversy that erupted into the

First Indo-Pakistani War which lasted from 1947 to 1949. Eventually, a United Nations-overseen ceasefire was agreed that left India in control of two-thirds of the contested region.

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

initially agreed to

Mountbatten's proposal that a plebiscite be held in the entire state as soon as hostilities ceased, and a UN-sponsored cease-fire was agreed to by both parties on 1 January 1949. No statewide plebiscite was held, however, for in 1954, after Pakistan began to receive arms from the United States, Nehru withdrew his support. The Indian Constitution came into force in Kashmir on 26 January 1950 with special clauses for the state.

Constitution

The Constitution of India was adopted by the

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

on 26 November 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950.

The constitution replaced the

Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act 1935 (25 & 26 Geo. 5. c. 42) was an Act of Parliament (UK), act passed by the British Parliament that originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest act that the British Parliament ever enact ...

as the country's fundamental governing document, and the

Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,

*

* was an independent dominion in the British Commonwealth of Nations existing between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950. Until its Indian independence movement, independence, India had be ...

became the

Republic of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area; the most populous country since 2023; and, since its independence in 1947, the world's most populous democracy. Bounded by ...

. To ensure

constitutional autochthony

In political science, constitutional autochthony is the process of asserting constitutional nationalism from an external legal or political power. The source of autochthony is the Greek word αὐτόχθων translated as ''springing from the la ...

, its framers repealed prior acts of the

British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

in Article 395. The constitution declares India a

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

,

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, secular, and democratic republic, assures its citizens

justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

,

equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

, and

liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, and endeavours to promote

fraternity

A fraternity (; whence, "wikt:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal order traditionally of men but also women associated together for various religious or secular ...

. Key features of the constitution were

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

for all adults,

Westminster style parliamentary system of government at the federal and state level, and independent judiciary.

The constitution also required the

Union Government and the

States and Territories of India

India is a federalism, federal union comprising 28 federated state, states and 8 union territory, union territories, for a total of 36 subnational entities. The states and union territories are further subdivided into 800 List of districts ...

to set ''reserved quotas or seats'', at particular percentage in Education Admissions, Employments, Political Bodies, Promotions, etc., for "socially and educationally backward citizens." The constitution has had

more than 100 amendments since it was enacted.

India celebrates its constitution on 26 January as

Republic Day

Republic Day is the name of a holiday in several countries to commemorate the day when they became republics.

List

January 1 January in Slovak Republic

The day of creation of Slovak republic. A national holiday since 1993. Officially calle ...

.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948 was fought between

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

over the

princely state of

Kashmir and Jammu from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four

Indo-Pakistan Wars fought between the two

newly independent nations. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after independence by launching tribal ''lashkar'' (militia) from

Waziristan

Waziristan (Persian language, Persian, Pashto, Ormuri, , ) is a mountainous region of the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The Waziristan region administratively splits among three districts: North Waziristan, Lower South Waziristan Dis ...

, in an effort to secure Kashmir, the future of which hung in the balance. A United Nations-mediated ceasefire took place on 5 January 1949.

Indian losses in the war totalled 1,104 killed and 3,154 wounded;

Pakistani, about 6,000 killed and 14,000 wounded.

Neutral assessments state

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

emerged victorious as it successfully defended the majority of the contested territory.

Governance and politics

India held its first national elections under the Constitution in

1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Cairo Fire, Black Saturday in Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, ...

, where a turnout of over 60% was recorded. The

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

won an overwhelming majority, and

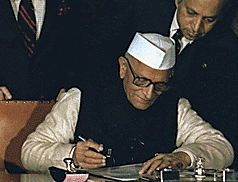

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

began a second term as prime minister. President Prasad was also elected to a second term by the electoral college of the first

Parliament of India

The Parliament of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Government of India, Government of the Republic of India. It is a bicameralism, bicameral legislature composed of the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok ...

.

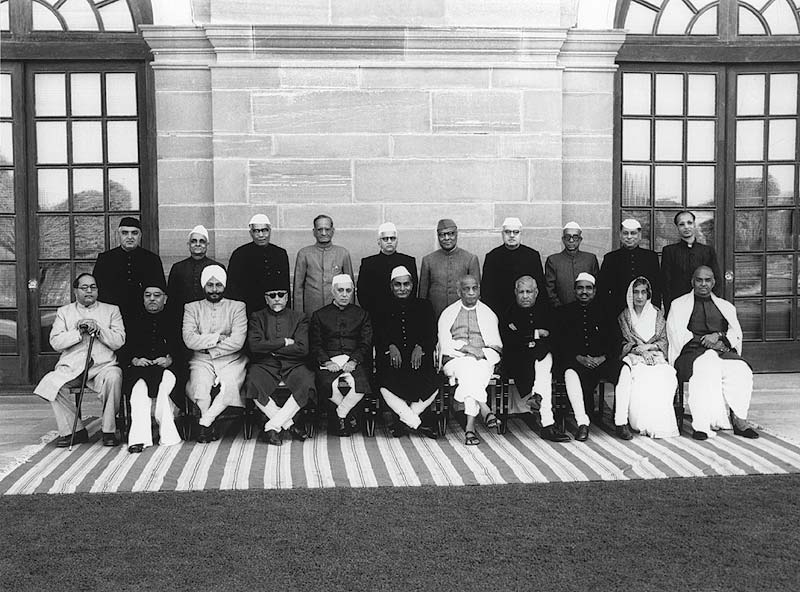

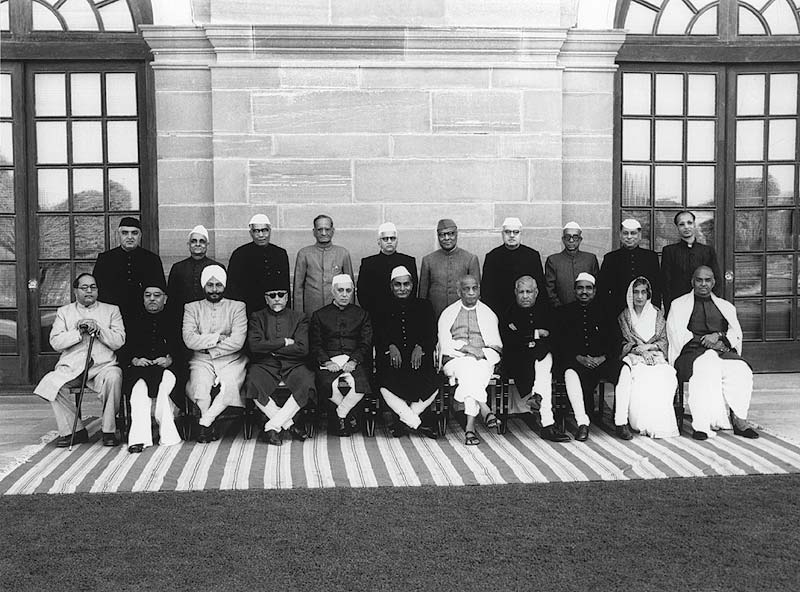

Nehru administration (1952–1964)

Nehru can be regarded as the founder of the modern Indian state. Parekh attributes this to the national philosophy Nehru formulated for India. For him, modernisation was the national philosophy, with seven goals: national unity, parliamentary democracy, industrialisation, socialism, development of the scientific temper, and non-alignment. In Parekh's opinion, the philosophy and the policies that resulted from this benefited a large section of society such as public sector workers, industrial houses, and middle and upper peasantry. However, it failed to benefit or satisfy the urban and rural poor, the unemployed and the

Hindu fundamentalists.

The death of Vallabhbhai Patel in 1950 left Nehru as the sole remaining iconic national leader, and soon the situation became such that Nehru could implement his vision for India without hindrance.

Nehru implemented economic policies based on

import substitution industrialisation

Import substitution industrialization (ISI) is a protectionist trade and economic policy that advocates replacing foreign imports with domestic production. It is based on the premise that a country should attempt to reduce its foreign dependency ...

and advocated a

mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

where the government-controlled

public sector

The public sector, also called the state sector, is the part of the economy composed of both public services and public enterprises. Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, pu ...

would co-exist with the

private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The private sector employs most of the workfo ...

. He believed the establishment of basic and heavy industry was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy. The government, therefore, directed investment primarily into key

public sector

The public sector, also called the state sector, is the part of the economy composed of both public services and public enterprises. Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, pu ...

industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies.

Nehru led the Congress to further election victories in 1957 and 1962. During his tenure, the Indian Parliament passed extensive reforms that increased the legal rights of women in Hindu society, and further legislated against caste discrimination and

untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

. Nehru advocated a strong initiative to enroll India's children to complete primary education, and thousands of schools, colleges and institutions of advanced learning, such as the

Indian Institutes of Technology

The Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) are a network of engineering and technology institutions in India. Established in 1950, they are under the purview of the Ministry of Education of the Indian Government and are governed by the Inst ...

, were founded across the nation. Nehru advocated a socialist model for the

economy of India

The economy of India is a Developing country, developing mixed economy with a notable public sector in strategic sectors.

*

*

*

* It is the world's fourth-largest economy by gross domestic product, nominal GDP and the third-largest by purch ...

. After India achieved independence, a formal model of planning was adopted, and accordingly the

Planning Commission, reporting directly to the Prime Minister, was established in 1950, with Nehru as the chairman. The commission was tasked with formulating

Five-Year Plans Five-year plan may refer to:

Nation plans

* Five-year plans of the Soviet Union, a series of nationwide centralized economic plans in the Soviet Union

* Five-Year Plans of Argentina, under Peron (1946–1955)

* Five-Year Plans of Bhutan, a series ...

for economic development which were shaped by the

Soviet model

Soviet-type economic planning (STP) is the specific model of centralized planning employed by Marxist–Leninist socialist states modeled on the economy of the Soviet Union.

The post-''perestroika'' analysis of the system of the Soviet econom ...

based on centralised and integrated national economic programs—no taxation for Indian farmers, minimum wage and benefits for blue-collar workers, and the

nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

of heavy industries such as steel, aviation, shipping, electricity, and mining. Village

common lands

The Generality Lands, Lands of the Generality or Common Lands () were about one-fifth of the territories of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, that were directly governed by the States-General. Unlike the seven provinces of Holland, Zeel ...

were seized, and an extensive public works and industrialisation campaign resulted in the construction of major dams, irrigation canals, roads, thermal and hydroelectric power stations, and many more.

States reorganisation

Potti Sreeramulu

Potti Sreeramulu (IAST: Poṭṭi Śrīrāmulu, ; 16 March 1901 – 16 December 1952) was an Indian freedom fighter known for his pivotal role in the creation of Andhra State. Revered as "Amarajeevi" ("Immortal Being"), he is remembered for h ...

's ''fast-unto-death'', and consequent death for the demand of an

Andhra State

Andhra State (IAST: ; ), created in 1953, was the official name of the State of Andhra Pradesh until 1956. The state was formed from Telugu-speaking districts of the erstwhile Madras State, which form two distinct cultural regions – Rayalas ...

in 1952 sparked a major re-shaping of the Indian Union. Nehru appointed the States Re-organisation Commission, upon whose recommendations the

States Reorganisation Act

The States Reorganisation Act, 1956 was a major reform of the boundaries of India's States and union territories of India, states and territories, organising them along linguistic lines.

Although additional changes to India's state boundaries ...

was passed in 1956. Old states were dissolved and new states created on the lines of shared linguistic and ethnic demographics. The separation of

Kerala

Kerala ( , ) is a States and union territories of India, state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile ...

and the

Telugu

Telugu may refer to:

* Telugu language, a major Dravidian language of South India

** Telugu literature, is the body of works written in the Telugu language.

* Telugu people, an ethno-linguistic group of India

* Telugu script, used to write the Tel ...

-speaking regions of

Madras State

Madras State was a state in the Indian Republic, which was in existence during the mid-20th century as a successor to the Madras Presidency of British India. The state came into existence on 26 January 1950 when the Constitution of India was ad ...

enabled the creation of an exclusively

Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

-speaking state of

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

. On 1 May 1960, the states of

Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

and

Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

were created out of the bilingual

Bombay State

Bombay State was a large Indian state created in 1950 from the erstwhile Bombay Province, with other regions being added to it in the succeeding years. Bombay Province (in British India roughly equating to the present-day Indian state of Mah ...

, and on 1 November 1966, the larger

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

state was divided into the smaller,

Punjabi-speaking

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

and

Haryanvi

Haryanvi (हरियाणवी or हरयाणवी) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken primarily in the Indian state of Haryana and the territory of Delhi. Haryanvi is considered to be part of the dialect group of Western Hindi, which a ...

-speaking

Haryana

Haryana () is a States and union territories of India, state located in the northern part of India. It was carved out after the linguistic reorganisation of Punjab, India, Punjab on 1 November 1966. It is ranked 21st in terms of area, with les ...

states.

Development of a multi-party system

In pre-independence India, the main parties were the Congress and the Muslim league. There were also many other parties such as the

Hindu mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

,

Justice party, the

Akali dal

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) (translation: ''Supreme Eternal Party'') is a Centre-right politics, centre-right Sikhism, Sikh-centric state political party in Punjab, India, Punjab, India. The party is the second-oldest in India, after Indian ...

, the

Communist party etc. during this period with limited or regional appeal. With the eclipse of the Muslim league due to partition, the Congress party was able to dominate Indian politics during the 1950s. This started breaking down during the 60s and 70s.This period saw formation of many new parties. These included those founded by former congress leaders such as the Swatantra party, many Socialist leaning parties, and the

Bharatiya Jan Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

, the political arm of the Hindu nationalist

RSS

RSS ( RDF Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication) is a web feed that allows users and applications to access updates to websites in a standardized, computer-readable format. Subscribing to RSS feeds can allow a user to keep track of many ...

.

Swatantra Party

On 4 June 1959, shortly after the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress,

C. Rajagopalachari

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and Indian independence ...

,

along with Murari Vaidya of the newly established Forum of Free Enterprise (FFE)

and

Minoo Masani

Minocher Rustom "Minoo" Masani (20 November 1905 – 27 May 1998) was an Indian politician, a leading figure of the erstwhile Swatantra Party. He was a three-time Member of Parliament, representing Gujarat's Rajkot (Lok Sabha constituency), Raj ...

, a

classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, eco ...

and critic of socialist leaning Nehru, announced the formation of the new

Swatantra Party

The Swatantra Party was an Indian classical liberal political party that existed from 1959 to 1974. It was founded by C. Rajagopalachari in reaction to what he felt was the Jawaharlal Nehru-dominated Indian National Congress's increasingly so ...

at a meeting in Madras.

Conceived by disgruntled heads of former princely states such as the Raja of Ramgarh, the Maharaja of Kalahandi and the Maharajadhiraja of Darbhanga, the party was conservative in character.

Later,

N. G. Ranga,

K. M. Munshi,

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

K. M. Cariappa and the Maharaja of Patiala joined the effort.

Rajagopalachari, Masani and Ranga also tried but failed to involve

Jayaprakash Narayan

Jayaprakash Narayan Srivastava (; 11 October 1902 – 8 October 1979), also known as JP and ''Lok Nayak'' (Hindi for "People's leader"), was an Indian politician, theorist and Indian independence activist, independence activist. He is mai ...

in the initiative.

In his short essay "Our Democracy", Rajagopalachari argued the necessity of a right-wing alternative to the Congress: "since ... the Congress Party has swung to the Left, what is wanted is not an ultra or outer-Left

iz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party, PSP but a strong and articulate Right."

Rajagopalachari also said the opposition must: "operate not privately and behind the closed doors of the party meeting, but openly and periodically through the electorate."

He outlined the goals of the Swatantra Party through twenty-one "fundamental principles" in the foundation document.

The party stood for equality and opposed government control over the private sector.

Rajagopalachari sharply criticised the bureaucracy and coined the term "

licence-permit Raj" to describe Nehru's elaborate system of permissions and licences required for an individual to set up a private enterprise. Rajagopalachari's personality became a rallying point for the party.

Rajagopalachari's efforts to build an anti-Congress front led to a patch-up with his former adversary

C. N. Annadurai

Conjeevaram Natarajan Annadurai (15 September 19093 February 1969), also known as Perarignar, was an Indian politician who was the founder and first general-secretary of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). He served as the fourth and last chi ...

of the

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; ; DMK) is an Indian political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu, where it is currently the ruling party, and the union territory of Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry, where it is currently the main ...

.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Annadurai grew close to Rajagopalachari and sought an alliance with the Swatantra Party for the

1962 Madras Legislative Assembly election

The third legislative assembly election to the Madras state (presently Tamil Nadu) was held on 21 February 1962. The Indian National Congress party, led by K. Kamaraj, won the election. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam made significant in-roads in th ...

s. Although there were occasional electoral pacts between the Swatantra Party and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), Rajagopalachari remained non-committal on a formal tie-up with the DMK due to its existing alliance with Communists whom he dreaded.

The Swatantra Party contested 94 seats in the Madras state assembly elections and won six

as well as won 18 parliamentary seats in the

1962 Lok Sabha elections.

Foreign policy and military conflicts

Nehru's foreign policy was the inspiration of the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

, of which India was a co-founder. Nehru maintained friendly relations with both the United States and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and encouraged the People's Republic of China to join the global community of nations. In 1956, when the

Suez Canal Company

Suez (, , , ) is a seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest city of the ...

was seized by the Egyptian government, an international conference voted 18–4 to take action against Egypt. India was one of the four backers of Egypt, along with

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

,

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, and the USSR. India had opposed the

partition of Palestine and the 1956 invasion of the

Sinai by Israel, the United Kingdom and France, but did not oppose the Chinese direct control over

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

,

and the suppression of a pro-democracy movement in

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

by the Soviet Union. Although Nehru disavowed nuclear ambitions for India, Canada and France aided India in the development of nuclear power stations for electricity. India also negotiated an agreement in 1960 with Pakistan on the just use of the waters of seven rivers shared by the countries. Nehru had visited Pakistan in 1953, but owing to political turmoil in Pakistan, no headway was made on the Kashmir dispute.

India has fought a total of four

wars/military conflicts with its neighbouring rival state Pakistan, two in this period. In the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, fought over the disputed territory of

Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

, Pakistan captured one-third of Kashmir (which India claims as its territory), and India captured three-fifths (which Pakistan claims as its territory). In the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, India attacked Pakistan on all fronts by crossing the international border after attempts by Pakistani troops to infiltrate Indian-controlled Kashmir by crossing the de facto border between India and Pakistan in Kashmir.

In 1961, after continual petitions for a peaceful handover, India

invaded and annexed the Portuguese colony of

Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

on the west coast of India.

In 1962 China and India engaged in the brief

Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispu ...

over the border in the

Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than list of h ...

. The war was a complete rout for the Indians and led to a refocusing on arms build-up and an improvement in relations with the United States. China withdrew from disputed territory in the contested Chinese

South Tibet Southern Tibet is a literal translation of the Chinese term "" (), which may refer to different geographic areas:

The southern part of Tibet, covering the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River Valley between Saga County to the west and Main ...

and Indian

North-East Frontier Agency

The North–East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union territory, U ...

that it crossed during the war. India disputes China's sovereignty over the smaller

Aksai Chin

Aksai Chin is a region administered by China partly in Hotan County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, and partly in Rutog County, Ngari Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region, Tibet, and constituting the easternmost portion of the larger Kashmir regio ...

territory that it controls on the western part of the Sino-Indian border.

1960s after Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru died on 27 May 1964, and

Lal Bahadur Shastri

Lal Bahadur Shastri (; born Lal Bahadur Srivastava; 2 October 190411 January 1966) was an Indian politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1964 to 1966. He previously served as Minister ...

succeeded him as prime minister. In 1965, India and Pakistan again

went to war over Kashmir, but without any definitive outcome or alteration of the Kashmir boundary. The

Tashkent Agreement

The Tashkent Declaration was signed between India and Pakistan on 10 January 1966 to resolve the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. Peace was achieved on 23 September through interventions by the Soviet Union and the United States, both of which pus ...

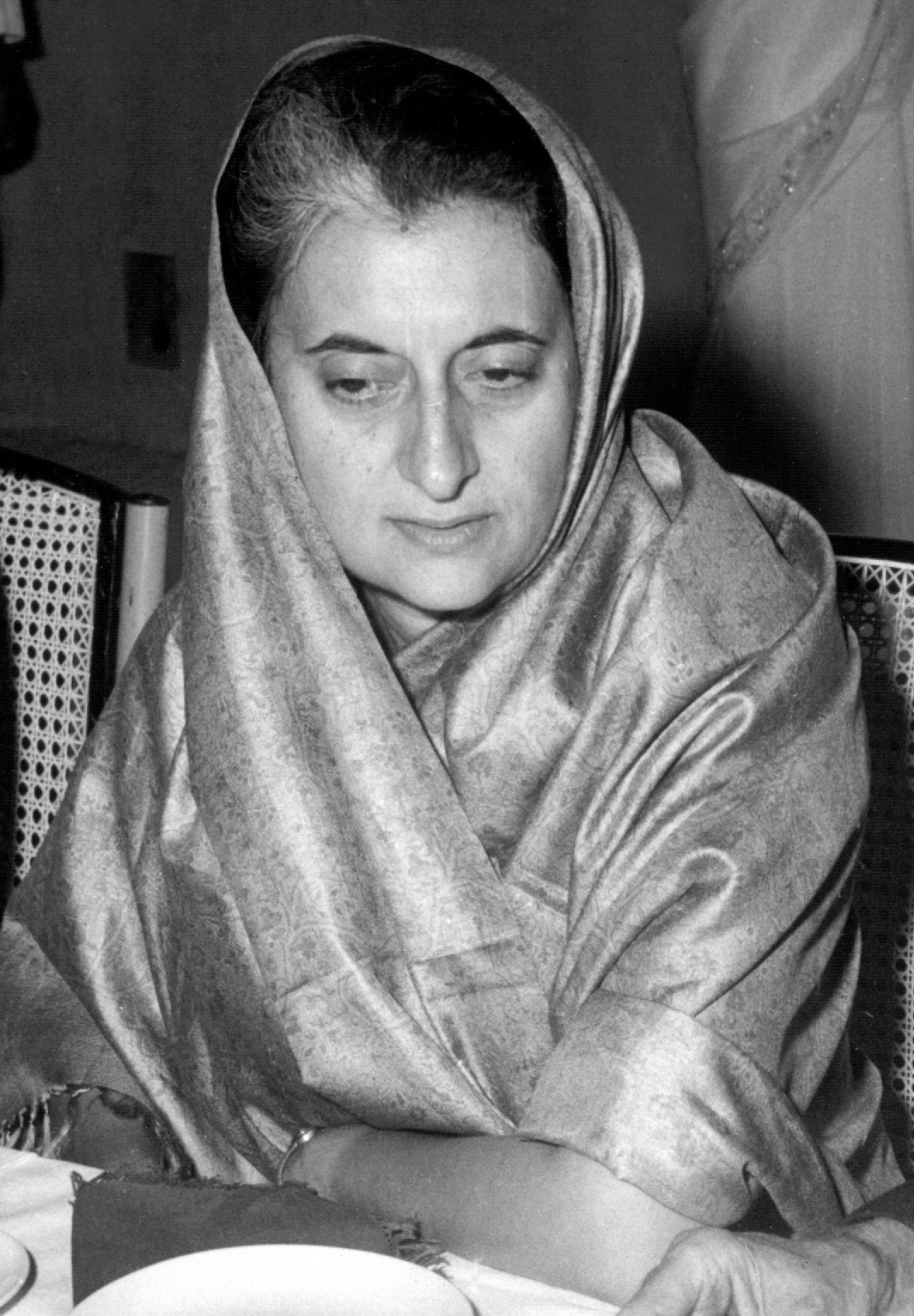

was signed under the mediation of the Soviet government, but Shastri died on the night after the signing ceremony. A leadership election resulted in the elevation of

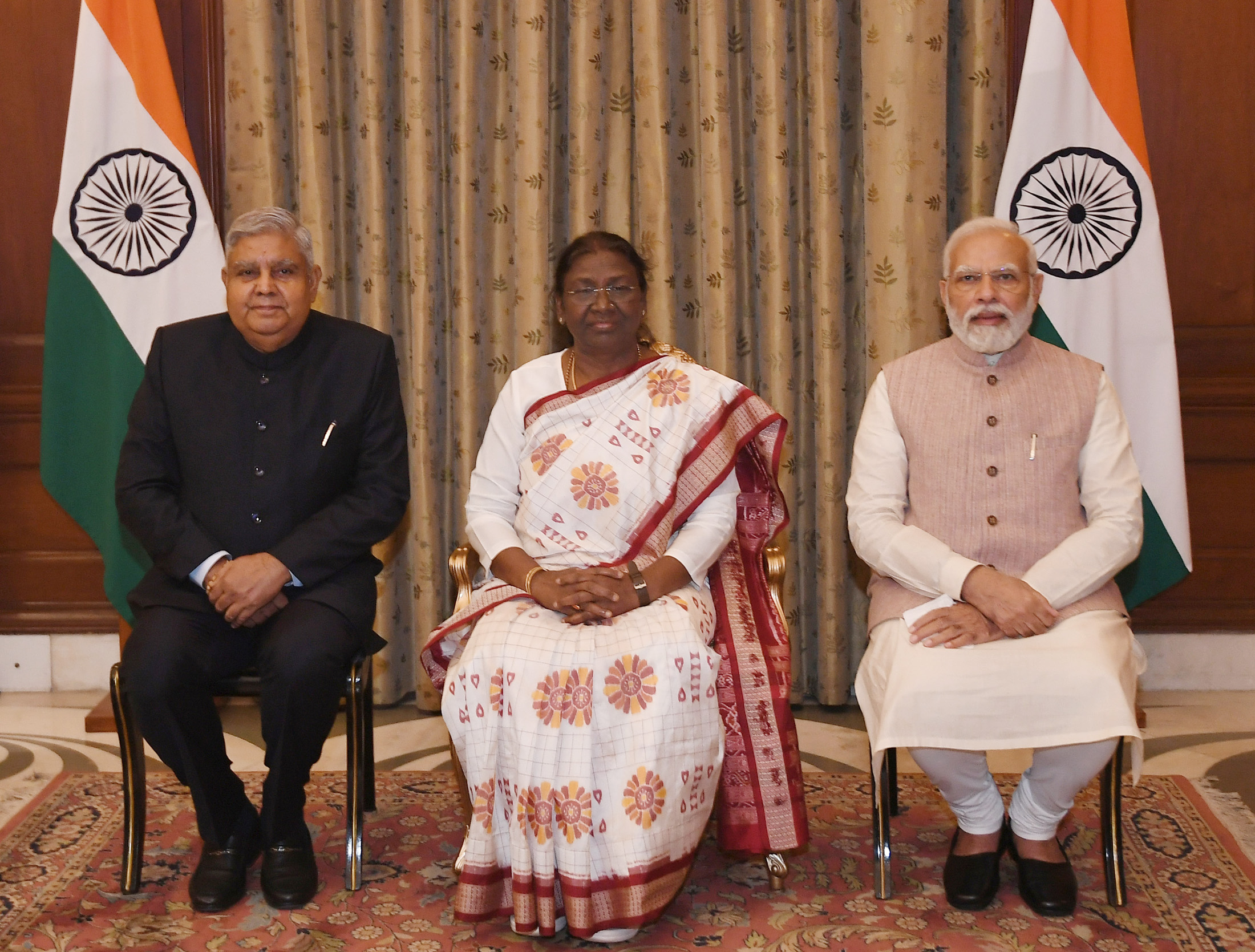

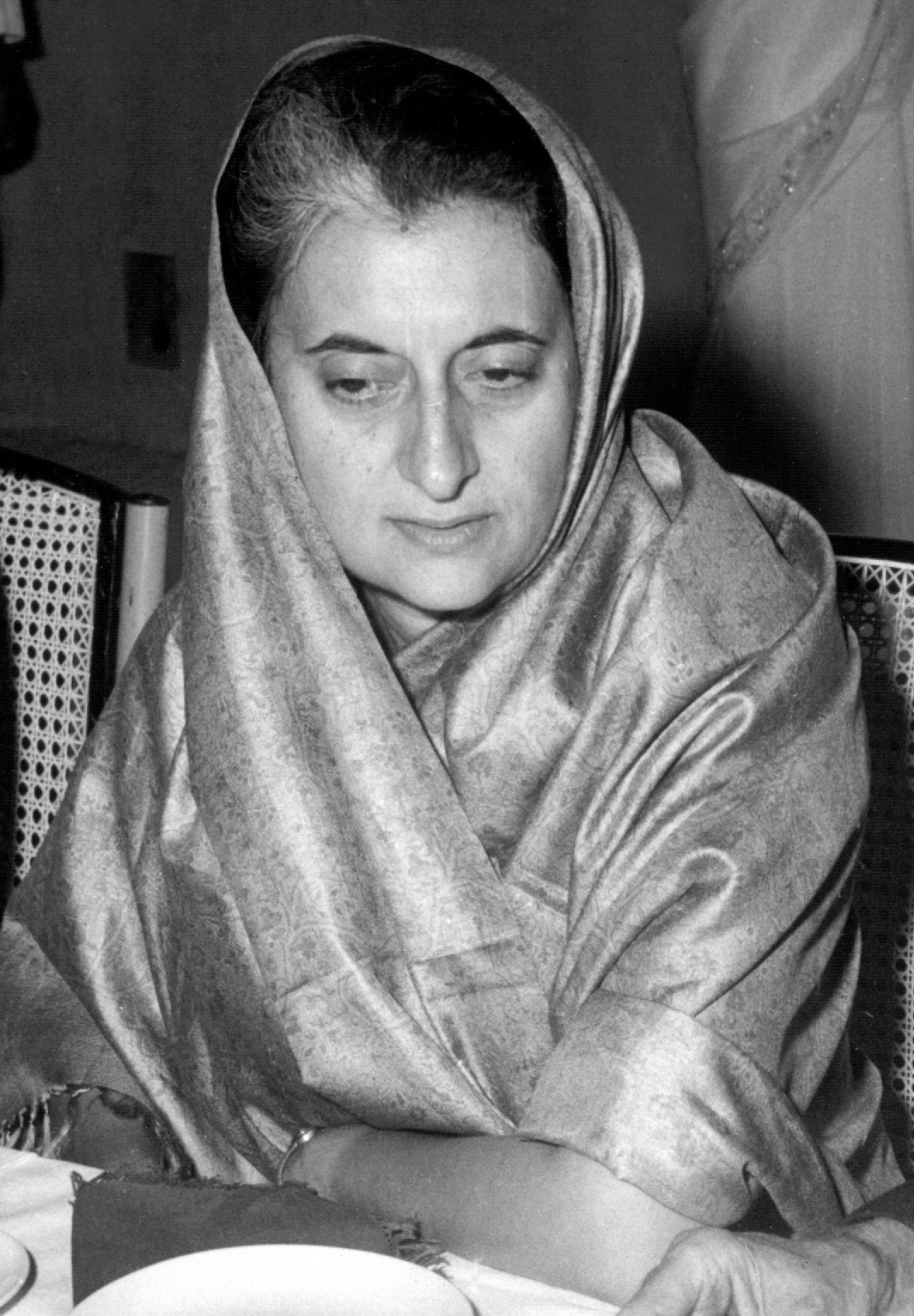

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

, Nehru's daughter who had been serving as Minister for Information and Broadcasting, as the third prime minister. She defeated right-wing leader

Morarji Desai

Morarji Ranchhodji Desai (29 February 1896 – 10 April 1995) was an Indian politician and Indian independence activist, independence activist who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India between 1977 and 1979 leading th ...

. The Congress Party won a reduced majority in the 1967 elections owing to widespread disenchantment over rising prices of commodities, unemployment, economic stagnation, and food crisis. Indira Gandhi had started on a rocky note after agreeing to a

devaluation

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national curre ...

of the

rupee

Rupee (, ) is the common name for the currency, currencies of

Indian rupee, India, Mauritian rupee, Mauritius, Nepalese rupee, Nepal, Pakistani rupee, Pakistan, Seychellois rupee, Seychelles, and Sri Lankan rupee, Sri Lanka, and of former cu ...

, which created much hardship for Indian businesses and consumers, and the import of wheat from the United States fell through due to political disputes.

In 1967, India and China again engaged with each other in

Sino-Indian War of 1967 after the PLA soldiers opened fire on the Indian soldiers who were making a fence on the border in Nathu La. The Indian forces successfully repelled Chinese forces and the outcome saw Chinese defeat with their withdrawal from Sikkim.

Morarji Desai entered Gandhi's government as deputy prime minister and finance minister, and with senior Congress politicians attempted to constrain Gandhi's authority. But following the counsel of her political advisor

P. N. Haksar, Gandhi resuscitated her popular appeal by a major shift towards socialist policies. She successfully ended the

Privy Purse

The Privy Purse is the British sovereign's private income, mostly from the Duchy of Lancaster. This amounted to £20.1 million in net income for the year to 31 March 2018.

Overview

The Duchy is a landed estate of approximately 46,000 acres (20 ...

guarantee for former Indian royalty, and waged a major offensive against party hierarchy over the nationalisation of India's banks. Although resisted by Desai and India's business community, the policy was popular with the masses. When Congress politicians attempted to oust Gandhi by suspending her Congress membership, Gandhi was empowered with a large exodus of members of parliament to her own Congress (R). The bastion of the Indian freedom struggle, the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

, had split in 1969. Gandhi continued to govern with a slim majority.

1970s

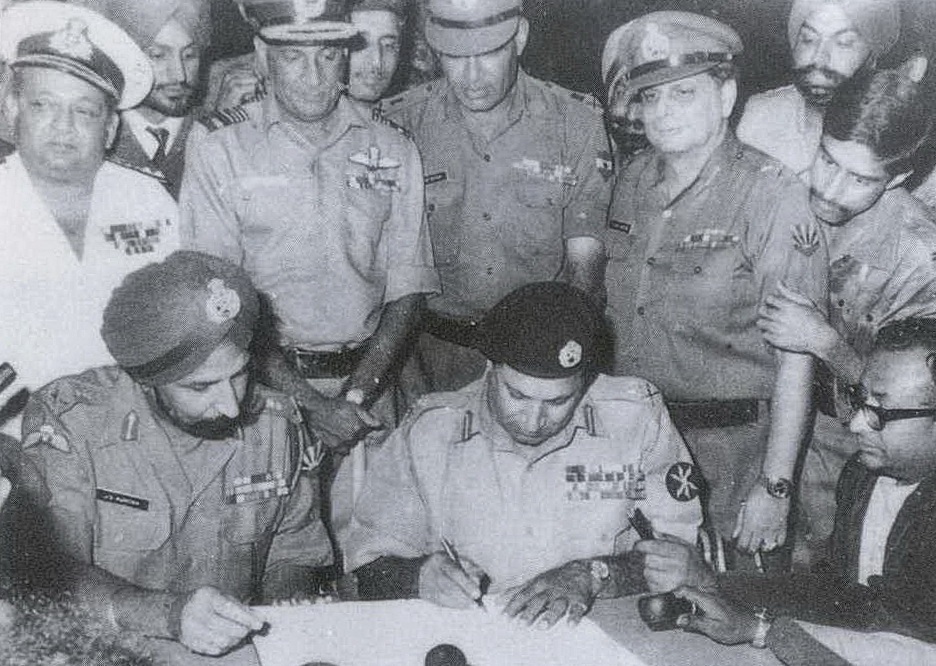

In 1971, Indira Gandhi and her Congress (R) were returned to power with a massively increased majority. The nationalisation of banks was carried out, and many other socialist economic and industrial policies enacted. India

intervened in the

Bangladesh War of Independence

The Bangladesh Liberation War (, ), also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, was an War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Bengali nationalism, Bengali nationalist and self-determination movement in East Pakistan, which res ...

, a civil war taking place in Pakistan's

Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

half, after millions of refugees had fled the persecution of the Pakistani army. The clash resulted in the independence of East Pakistan, which became known as

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's elevation to immense popularity. Relations with the United States grew strained, and India signed a 20-year treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union—breaking explicitly for the first time from non-alignment. In 1974, India tested

its first nuclear weapon in the desert of

Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; Literal translation, lit. 'Land of Kings') is a States and union territories of India, state in northwestern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the List of states and union territories of ...

, near

Pokhran

Pokhran (official spelling Pokaran; ) is a town and a municipality located 112 km east of Jaisalmer city in the Jaisalmer district of the Indian state of Rajasthan. It is situated in the Thar Desert region. Surrounded by rocks, sand and ...

.

Merger of Sikkim

In 1973, anti-royalist riots took place in the

Kingdom of Sikkim

The Kingdom of Sikkim (Classical Tibetan and , ''Drenjong'', , ''Sikimr Gyalkhab'') officially Dremoshong (Classical Tibetan and ) until the 1800s, was a hereditary monarchy in the Eastern Himalayas which existed from 1642 to 16 May 1975 ...

. In 1975, the Prime Minister of

Sikkim

Sikkim ( ; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Koshi Province of Nepal in the west, and West Bengal in the ...

appealed to the

Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India (ISO: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Government of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the People). The President o ...

for Sikkim to become a state of India. In April of that year, the

Indian Army

The Indian Army (IA) (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the Land warfare, land-based branch and largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head ...

took over the city of

Gangtok

Gangtok (, ) is the capital and the most populous city of the Indian state of Sikkim. The seat of East Sikkim district, eponymous district, Gangtok is in the eastern Himalayas, Himalayan range, at an elevation of . The city's population of 100 ...

and disarmed the Chogyal's palace guards. Thereafter,

a referendum was held in which 97.5 percent of voters supported abolishing the monarchy, effectively approving union with India.

India is said to have stationed 20,000–40,000 troops in a country of only 200,000 during the referendum. On 16 May 1975, Sikkim became the 22nd state of the Indian Union, and the monarchy was abolished. To enable the incorporation of the new state, the

Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India (ISO: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Government of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the People). The President o ...

amended the

Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India is the supreme legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and ...

. First, the

35th Amendment laid down a set of conditions that made Sikkim an "associate state", a special designation not used by any other state. A month later, the

36th Amendment repealed the 35th Amendment, and made Sikkim a full state, adding its name to the

First Schedule of the Constitution.

Formation of Northeastern states

In the

Northeast India

Northeast India, officially the North Eastern Region (NER), is the easternmost region of India representing both a geographic and political Administrative divisions of India, administrative division of the country. It comprises eight States and ...

, the state of

Assam

Assam (, , ) is a state in Northeast India, northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra Valley, Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . It is the second largest state in Northeast India, nor ...

was divided into several states beginning in 1970 within the borders of what was then Assam. In 1963, the Naga Hills district became the 16th state of India under the name of

Nagaland

Nagaland () is a States and union territories of India, state in the northeast India, north-eastern region of India. It is bordered by the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Assam to the west, Manipur to the south, and the Naga Sel ...

. Part of

Tuensang

Tuensang () is a town located in the northeastern part of the Indian state of Nagaland. It is the headquarters of the Tuensang District and has a population of 36,774. The town was founded in 1947 for the purpose of administrating the erstwhile ...

was added to Nagaland. In 1970, in response to the demands of the

Khasi,

Jaintia and

Garo people

The Garo people are a Tibeto-Burman ethnic group who live mostly in the Northeast Indian state of Meghalaya, with a smaller number in neighbouring Bangladesh. They are the second-largest indigenous people in Meghalaya after the Khasi and c ...

of the

Meghalaya Plateau, the districts embracing the

Khasi Hills

The Khasi Hills () are a low mountain formation on the Shillong Plateau in the Meghalaya state of India. The Khasi Hills are part of the Garo-Khasi-Jaintia range and connect with the Purvanchal Range and the larger Patkai Range further east. The ...

,

Jaintia Hills

The Khasi and Jaintia Hills are a mountainous region in India that was mainly part of Assam and Meghalaya. This area is now part of the present Indian constitutive state of Meghalaya (formerly part of Assam), which includes the present distri ...

, and

Garo Hills

The Garo Hills (IPA: ˈgɑ:ro:) are part of the Garo-Khasi range in the Meghalaya state of India. They are inhabited by the Garo people. It is one of the wettest places in the world. The range is part of the Meghalaya subtropical forests ecor ...

were formed into an autonomous state within Assam; in 1972 this became a separate state under the name of

Meghalaya

Meghalaya (; "the abode of clouds") is a states and union territories of India, state in northeast India. Its capital is Shillong. Meghalaya was formed on 21 January 1972 by carving out two districts from the Assam: the United Khasi Hills an ...

. In 1972,

Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northeast India. It was formed from the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and India declared it as a state on 20 February 1987. Itanagar is its capital and la ...

(the

North-East Frontier Agency

The North–East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union territory, U ...

) and

Mizoram