History of Australia (1788–1850) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Australia from 1788 to 1850 covers the early British colonial period of Australia's history. This started with the arrival in 1788 of the First Fleet of British ships at

Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended

Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended  On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need. The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years. Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again. Phillip and La Pérouse never met. La Pérouse is remembered in a Sydney suburb of that name. Various other French geographical names along the Australian coast also date from this voyage.

On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need. The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years. Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again. Phillip and La Pérouse never met. La Pérouse is remembered in a Sydney suburb of that name. Various other French geographical names along the Australian coast also date from this voyage.

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers – most notably

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers – most notably  In 1792, two French ships, ''La Recherche'' and ''L'Espérance'' anchored in a harbour near Tasmania's southernmost point they called Recherche Bay. This was at a time when Britain and France were trying to be the first European powers to discover and colonise Australia. The expedition led by Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux carried scientists and cartographers, gardeners, artists and hydrographers who, variously, planted, identified, mapped, marked, recorded and documented the environment and the people of the new lands that they encountered at the behest of the fledgling Société d'Histoire Naturelle.

White settlement began with a consignment of English convicts, guarded by a detachment of the Royal Marines, a number of whom subsequently stayed in the colony as settlers. Their view of the colony and their place in it was eloquently stated by Captain David Collins: "From the disposition to crimes and the incorrigible character of the major part of the colonists, an odium was, from the first, illiberally thrown upon the settlement; and the word "Botany Bay" became a term of reproach that was indiscriminately cast upon every one who resided in New South Wales. But let the reproach light upon those who have used it as such... if the honour of having deserved well of one's country be attainable by sacrificing good name, domestic comforts, and dearest connections in her service, the officers of this settlement have justly merited that distinction".

In 1792, two French ships, ''La Recherche'' and ''L'Espérance'' anchored in a harbour near Tasmania's southernmost point they called Recherche Bay. This was at a time when Britain and France were trying to be the first European powers to discover and colonise Australia. The expedition led by Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux carried scientists and cartographers, gardeners, artists and hydrographers who, variously, planted, identified, mapped, marked, recorded and documented the environment and the people of the new lands that they encountered at the behest of the fledgling Société d'Histoire Naturelle.

White settlement began with a consignment of English convicts, guarded by a detachment of the Royal Marines, a number of whom subsequently stayed in the colony as settlers. Their view of the colony and their place in it was eloquently stated by Captain David Collins: "From the disposition to crimes and the incorrigible character of the major part of the colonists, an odium was, from the first, illiberally thrown upon the settlement; and the word "Botany Bay" became a term of reproach that was indiscriminately cast upon every one who resided in New South Wales. But let the reproach light upon those who have used it as such... if the honour of having deserved well of one's country be attainable by sacrificing good name, domestic comforts, and dearest connections in her service, the officers of this settlement have justly merited that distinction".

Convicts were usually sentenced to seven or fourteen years' penal servitude, or "for the term of their natural lives". Often these sentences had been commuted from the death sentence, which was technically the punishment for a wide variety of crimes. Upon arrival in a penal colony, convicts would be assigned to various kinds of work. Those with trades were given tasks to fit their skills (stonemasons, for example, were in very high demand) while the unskilled were assigned to work gangs to build roads and do other such tasks. Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.

Where possible, convicts were assigned to free settlers who would be responsible for feeding and disciplining them; in return for this, the settlers were granted land. This system reduced the workload on the central administration. Those convicts who weren't assigned to settlers were housed at barracks such as the Hyde Park Barracks or the

Convicts were usually sentenced to seven or fourteen years' penal servitude, or "for the term of their natural lives". Often these sentences had been commuted from the death sentence, which was technically the punishment for a wide variety of crimes. Upon arrival in a penal colony, convicts would be assigned to various kinds of work. Those with trades were given tasks to fit their skills (stonemasons, for example, were in very high demand) while the unskilled were assigned to work gangs to build roads and do other such tasks. Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.

Where possible, convicts were assigned to free settlers who would be responsible for feeding and disciplining them; in return for this, the settlers were granted land. This system reduced the workload on the central administration. Those convicts who weren't assigned to settlers were housed at barracks such as the Hyde Park Barracks or the  Convict discipline was harsh; convicts who would not work or who disobeyed orders were punished by flogging, being put in stricter confinement (e.g. leg-irons), or being transported to a stricter penal colony. The penal colonies at Port Arthur in

Convict discipline was harsh; convicts who would not work or who disobeyed orders were punished by flogging, being put in stricter confinement (e.g. leg-irons), or being transported to a stricter penal colony. The penal colonies at Port Arthur in

From about 1815 the colony, under the governorship of

From about 1815 the colony, under the governorship of

*1835 – the ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'', (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been ''

*1835 – the ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'', (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been '' *28 December 1836 – the British province of

*28 December 1836 – the British province of

While the actual date of original exploration in Australia is unknown, there is evidence of exploration by William Dampier in 1699, and the First Fleet arrived in 1788, eighteen years after Lt. James Cook surveyed and mapped the entire east coast aboard HM Bark ''Endeavour'' in 1770. In October 1795

While the actual date of original exploration in Australia is unknown, there is evidence of exploration by William Dampier in 1699, and the First Fleet arrived in 1788, eighteen years after Lt. James Cook surveyed and mapped the entire east coast aboard HM Bark ''Endeavour'' in 1770. In October 1795  Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in ''The Investigator'' led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Eora man

Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in ''The Investigator'' led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Eora man  In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. European diseases decimated Aboriginal populations, and the occupation of land and degradation of food resources sometimes led to starvation. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits.

According to the historian

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. European diseases decimated Aboriginal populations, and the occupation of land and degradation of food resources sometimes led to starvation. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits.

According to the historian

From 1788 until the 1850s, the governance of the colonies, including most policy decision-making, was largely in the hands of the governors, who were directly responsible to the government in London ( Home Office until 1794;

From 1788 until the 1850s, the governance of the colonies, including most policy decision-making, was largely in the hands of the governors, who were directly responsible to the government in London ( Home Office until 1794;  The New South Wales Act 1823 by the

The New South Wales Act 1823 by the

In 1840, the

In 1840, the

The instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited. The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the

The instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited. The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the

In early colonial times, Church of England clergy worked closely with the

In early colonial times, Church of England clergy worked closely with the

Australian composers who published musical works in this period include Francis Hartwell Henslowe,

Australian composers who published musical works in this period include Francis Hartwell Henslowe,

*Duyker, Edward & Maryse. 2001. ''Voyage to Australia and the Pacific 1791–1793''. Melbourne University Press. . *Duyker, Edward & Maryse. 2003. ''Citizen Labillardière – A Naturalist's Life in Revolution and Exploration''. The Miegunyah Press. . *Horner, Frank. 1995. ''Looking for La Pérouse''. Melbourne University Press. . *Lepailleur, François-Maurice. 1980. ''Land of a Thousand Sorrows. The Australian Prison Journal 1840–1842, of the Exiled Canadien'' Patriote, ''François-Maurice Lepailleur''. Trans. and edited by F. Murray Greenwood. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver. . * John Holland Rose, Rose, J. Holland; Newton, A. P.; Benians, E. A. (1968), '' The Cambridge History of the British Empire'', Volume II—The Growth of the New Empire 1783–1870. Available at the

Australian History

page a

Project Gutenberg of Australia

- digitised versions of many old books {{DEFAULTSORT:History of Australia (1788-1850) History of Australia (1788–1850), 19th century in Australia

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman ...

on the lands of the Eora, and the establishment of the penal colony of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

as part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

. It further covers the European scientific exploration

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

of the continent and the establishment of the other Australian colonies that make up the modern states of Australia.

After several years of privation, the penal colony gradually expanded and developed an economy based on farming, fishing, whaling, trade with incoming ships, and construction using convict labour. By 1820, however, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

. From 1816 penal transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their d ...

to Australia increased rapidly and the number of free settlers grew steadily. Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony in 1825, and free settlements were established at the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just Swan River, was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, and it ...

in Western Australia (1829), the Province of South Australia (1836), and in the Port Philip District (1836). The grazing of cattle and sheep expanded inland, leading to increasing conflict with Aboriginal people on their traditional lands.

The growing population of free settlers, former convicts and Australian-born currency lads and lasses led to public demands for representative government. Penal transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840 and a semi-elected Legislative Council was established in 1842. In 1850 Britain granted Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly-created colony of Victoria semi-representative Legislative Councils.

British settlement led to a decline in the Aboriginal

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

population and the disruption of their cultures due to introduced diseases, violent conflict and dispossession of their traditional lands. Aboriginal resistance to British encroachment on their land often led to reprisals from settlers including massacres of Aboriginal people. Many Aboriginal people, however, sought an accommodation with the settlers and established viable communities, often on small areas of their traditional lands, where many aspects of their cultures were maintained.

Colonisation

The decision to establish a colony in Australia was made byThomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney

Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney (24 February 1733 – 30 June 1800) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1754 to 1783 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Sydney. He held several important Cabinet posts in ...

. This was taken for two reasons: the ending of transportation of criminals to North America following the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

, as well as the need for a base in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

to counter French expansion. Approximately 50,000 convicts are estimated to have been transported to the colonies over 150 years. The First Fleet which established the first colony was an unprecedented project for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

, as well as the first forced migration of settlers to a newly established colony.

Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended

Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refe ...

, then known to the local Gweagal people as Kamay, as a suitable site. Banks accepted an offer of assistance from the American Loyalist James Matra in July 1783. Matra had visited Botany Bay with Banks in 1770 as a junior officer on the ''Endeavour'' commanded by James Cook. Under Banks's guidance, he rapidly produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (24 August 1783), with a fully developed set of reasons for a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).

Following an interview with Secretary of State Lord Sydney

Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney (24 February 1733 – 30 June 1800) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1754 to 1783 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Sydney. He held several important Cabinet posts in ...

in March 1784, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers. Matra's plan can be seen to have “provided the original blueprint for settlement in New South Wales”. A cabinet memorandum December 1784 shows the Government had Matra's plan in mind when considering the creation of a settlement in New South Wales. ''The London Chronicle'' of 12 October 1786 said: “Mr. Matra, an Officer of the Treasury, who, sailing with Capt. Cook, had an opportunity of visiting Botany Bay, is the Gentleman who suggested the plan to Government of transporting convicts to that island”. The Government also incorporated into the colonisation plan the project for settling Norfolk Island, with its attractions of timber and flax, proposed by Banks's Royal Society colleagues, Sir John Call and Sir George Young.

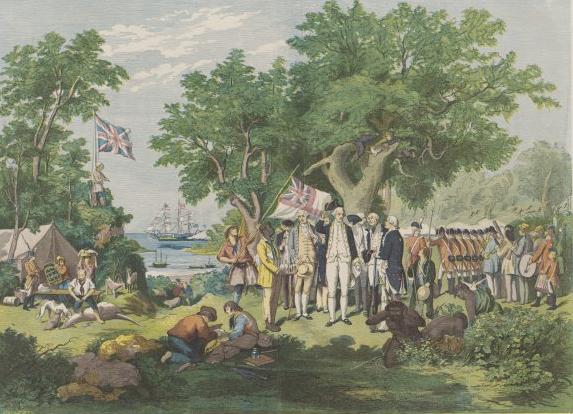

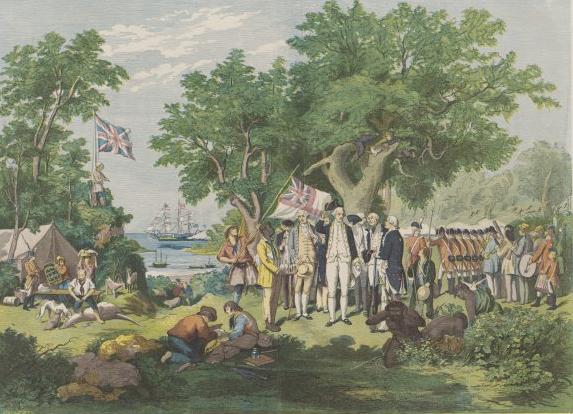

On 13 May 1787, the First Fleet of 11 ships and about 1,530 people (736 convicts, 17 convicts' children, 211 marines, 27 marines' wives, 14 marines' children and about 300 officers and others) under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Greenwich Hospital School from June 1751 unti ...

set sail for Botany Bay. A few days after arrival at Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refe ...

the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman ...

where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove ( Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central Sydney loca ...

, known by the Indigenous name Warrane, on 26 January 1788. This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port J ...

. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip famously described as:

Phillip named the settlement after the

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, Thomas Townshend, 1st Baron Sydney (Viscount Sydney

Viscount Sydney (an alternative spelling of the surname Sidney) is a title that has been created twice. The title was elevated twice from a barony, and once into an earldom.

First creation (1689)

The first creation came on 9 April 1689 when He ...

from 1789). The only people at the flag raising ceremony and the formal taking of possession of the land in the name of King George III were Phillip and a few dozen marines and officers from the ''Supply'', the rest of the ship's company and the convicts witnessing it from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet were unable to leave Botany Bay until later on 26 January because of a tremendous gale. The new colony was formally proclaimed as the Colony of New South Wales on 7 February.

On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need. The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years. Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again. Phillip and La Pérouse never met. La Pérouse is remembered in a Sydney suburb of that name. Various other French geographical names along the Australian coast also date from this voyage.

On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage that had taken them from Brest, around Cape Horn, up the coast from Chile to California, north-west to Kamchatka, south-east to Easter Island, north-west to Macao, and on to the Philippines, the Friendly Isles, Hawaii and Norfolk Island. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need. The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years. Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again. Phillip and La Pérouse never met. La Pérouse is remembered in a Sydney suburb of that name. Various other French geographical names along the Australian coast also date from this voyage.

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers – most notably

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers – most notably Watkin Tench

Lieutenant General Watkin Tench (6 October 1758 – 7 May 1833) was a British marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first European settlement in Australia ...

– wrote journals and accounts that tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement. Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of New South Wales. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were few and far between. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney – many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its "passengers" through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791 however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

In 1792, two French ships, ''La Recherche'' and ''L'Espérance'' anchored in a harbour near Tasmania's southernmost point they called Recherche Bay. This was at a time when Britain and France were trying to be the first European powers to discover and colonise Australia. The expedition led by Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux carried scientists and cartographers, gardeners, artists and hydrographers who, variously, planted, identified, mapped, marked, recorded and documented the environment and the people of the new lands that they encountered at the behest of the fledgling Société d'Histoire Naturelle.

White settlement began with a consignment of English convicts, guarded by a detachment of the Royal Marines, a number of whom subsequently stayed in the colony as settlers. Their view of the colony and their place in it was eloquently stated by Captain David Collins: "From the disposition to crimes and the incorrigible character of the major part of the colonists, an odium was, from the first, illiberally thrown upon the settlement; and the word "Botany Bay" became a term of reproach that was indiscriminately cast upon every one who resided in New South Wales. But let the reproach light upon those who have used it as such... if the honour of having deserved well of one's country be attainable by sacrificing good name, domestic comforts, and dearest connections in her service, the officers of this settlement have justly merited that distinction".

In 1792, two French ships, ''La Recherche'' and ''L'Espérance'' anchored in a harbour near Tasmania's southernmost point they called Recherche Bay. This was at a time when Britain and France were trying to be the first European powers to discover and colonise Australia. The expedition led by Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux carried scientists and cartographers, gardeners, artists and hydrographers who, variously, planted, identified, mapped, marked, recorded and documented the environment and the people of the new lands that they encountered at the behest of the fledgling Société d'Histoire Naturelle.

White settlement began with a consignment of English convicts, guarded by a detachment of the Royal Marines, a number of whom subsequently stayed in the colony as settlers. Their view of the colony and their place in it was eloquently stated by Captain David Collins: "From the disposition to crimes and the incorrigible character of the major part of the colonists, an odium was, from the first, illiberally thrown upon the settlement; and the word "Botany Bay" became a term of reproach that was indiscriminately cast upon every one who resided in New South Wales. But let the reproach light upon those who have used it as such... if the honour of having deserved well of one's country be attainable by sacrificing good name, domestic comforts, and dearest connections in her service, the officers of this settlement have justly merited that distinction".

Convicts and free settlers

When the ''Bellona'' transport came to anchor in Sydney Cove on 16 January 1793, she brought with her the first immigrant free settlers. They were: Thomas Rose, a farmer from Dorset, his wife and four children; he was allowed a grant of 120 acres; Frederic Meredith, who had formerly been at Sydney with HMS ''Sirius''; Thomas Webb (who had also been formerly at Sydney with the ''Sirius''), his wife, and his nephew, Joseph Webb; Edward Powell, who had formerly been at Sydney with the ''Juliana'' transport, and who married a free woman after his arrival. Thomas Webb and Edward Powell each received a grant of 80 acres; and Joseph Webb and Frederic Meredith received 60 acres each. The conditions they had come out under were that they should be provided with a free passage, be furnished with agricultural tools and implements by the Government, have two years' provisions, and have grants of land free of expense. They were likewise to have the labour of a certain number of convicts, who were also to be provided with two years' rations and one year's clothing from the public stores. The land assigned to them was some miles to the westward of Sydney, at a place named by the settlers, "Liberty Plains" on the Country of the Wangal people. It is now the area covered mainly by the suburbs of Strathfield and Homebush. One in three convicts transported after 1798 was Irish, about a fifth of whom were transported in connection with thepolitical

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

and agrarian disturbances common in Ireland at the time. While the settlers were reasonably well-equipped, little consideration had been given to the skills required to make the colony self-supporting: few of the first-wave convicts had farming or trade experience (nor the soldiers), and the lack of understanding of Australia's seasonal patterns saw initial attempts at farming fail, leaving only what animals and birds the soldiers were able to shoot. The colony nearly starved, and Phillip was forced to send a ship to Batavia (Jakarta) for supplies. Some relief arrived with the Second Fleet in 1790, but life was extremely hard for the first few years of the colony.

The Second Fleet in 1790 brought to Sydney two men who were to play important roles in the colony's future. One was D'Arcy Wentworth

D'Arcy Wentworth (14 February 1762 – 7 July 1827) was an Irish surgeon, the first paying passenger to arrive in the new colony of New South Wales. He served under the first seven governors of the Colony, and from 1810 to 1821, he was ''great ...

, whose son, William Charles, went on to be an explorer, to found Australia's first newspaper and to become a leader of the movement to abolish convict transportation and establish representative government. The other was John Macarthur John MacArthur or Macarthur may refer to:

*J. Roderick MacArthur (1920–1984), American businessman

*John MacArthur (American pastor) (born 1939), American evangelical minister, televangelist, and author

* John Macarthur (priest), 20th-century pro ...

, a Scottish army officer and founder of the Australian wool industry, which laid the foundations of Australia's future prosperity. Macarthur was a turbulent element: in 1808 he was one of the leaders of the Rum Rebellion

The Rum Rebellion of 1808 was a ''coup d'état'' in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose Governor William Bligh. Australia's first and only military coup, the name derives fr ...

against the governor, William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift i ...

.

Convicts were usually sentenced to seven or fourteen years' penal servitude, or "for the term of their natural lives". Often these sentences had been commuted from the death sentence, which was technically the punishment for a wide variety of crimes. Upon arrival in a penal colony, convicts would be assigned to various kinds of work. Those with trades were given tasks to fit their skills (stonemasons, for example, were in very high demand) while the unskilled were assigned to work gangs to build roads and do other such tasks. Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.

Where possible, convicts were assigned to free settlers who would be responsible for feeding and disciplining them; in return for this, the settlers were granted land. This system reduced the workload on the central administration. Those convicts who weren't assigned to settlers were housed at barracks such as the Hyde Park Barracks or the

Convicts were usually sentenced to seven or fourteen years' penal servitude, or "for the term of their natural lives". Often these sentences had been commuted from the death sentence, which was technically the punishment for a wide variety of crimes. Upon arrival in a penal colony, convicts would be assigned to various kinds of work. Those with trades were given tasks to fit their skills (stonemasons, for example, were in very high demand) while the unskilled were assigned to work gangs to build roads and do other such tasks. Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.

Where possible, convicts were assigned to free settlers who would be responsible for feeding and disciplining them; in return for this, the settlers were granted land. This system reduced the workload on the central administration. Those convicts who weren't assigned to settlers were housed at barracks such as the Hyde Park Barracks or the Parramatta Female Factory

The Parramatta Female Factory, is a National Heritage List (Australia), National Heritage Listed place and has three original sandstone buildings and the sandstone gaol walls. The Parramatta Female Factory was designed by Convicts in Australia, c ...

.

Convict discipline was harsh; convicts who would not work or who disobeyed orders were punished by flogging, being put in stricter confinement (e.g. leg-irons), or being transported to a stricter penal colony. The penal colonies at Port Arthur in

Convict discipline was harsh; convicts who would not work or who disobeyed orders were punished by flogging, being put in stricter confinement (e.g. leg-irons), or being transported to a stricter penal colony. The penal colonies at Port Arthur in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and Moreton Bay

Moreton Bay is a bay located on the eastern coast of Australia from central Brisbane, Queensland. It is one of Queensland's most important coastal resources. The waters of Moreton Bay are a popular destination for recreational anglers and are ...

in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, for instance, were stricter than the one at Sydney, and the one at Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together w ...

was strictest of all. Convicts were assigned to work gangs to build roads, buildings, and the like. Female convicts, who made up 20% of the convict population, were usually assigned as domestic help to soldiers. Those convicts who behaved were eventually issued with ticket of leave

A ticket of leave was a document of parole issued to convicts who had shown they could now be trusted with some freedoms. Originally the ticket was issued in Britain and later adapted by the United States, Canada, and Ireland.

Jurisdictions ...

, which allowed them a certain degree of freedom. Those who saw out their full sentences or were granted a pardon usually remained in Australia as free settlers, and were able to take on convict servants themselves.

In 1789 former convict James Ruse

James Ruse (9 August17595 September 1837) was a Cornish farmer who, at age 23, was convicted of burglary and was sentenced to seven years' transportation. He arrived at Sydney Cove, New South Wales, on the First Fleet with 18 months of his ...

produced the first successful wheat harvest in NSW. He repeated this success in 1790 and, because of the pressing need for food production in the colony, was rewarded by Governor Phillip with the first land grant made in New South Wales. Ruse's 30-acre grant at Rose Hill, near Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

, was aptly named 'Experiment Farm'. This was the colony's first successful farming enterprise, and Ruse was soon joined by others. The colony began to grow enough food to support itself, and the standard of living for the residents gradually improved.

In 1804 the Castle Hill convict rebellion was led by around 200 escaped, mostly Irish convicts, although it was broken up quickly by the New South Wales Corps

The New South Wales Corps (sometimes called The Rum Corps) was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia, in fortifying ...

. On 26 January 1808, there was a military rebellion against Governor Bligh led by John Macarthur John MacArthur or Macarthur may refer to:

*J. Roderick MacArthur (1920–1984), American businessman

*John MacArthur (American pastor) (born 1939), American evangelical minister, televangelist, and author

* John Macarthur (priest), 20th-century pro ...

. Following this, Governor Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; gd, Lachann MacGuaire; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie se ...

was given a mandate to restore government and discipline in the colony. When he arrived in 1810, he forcibly deported the NSW Corps and brought the 73rd regiment to replace them.

Growth of free settlement

From about 1815 the colony, under the governorship of

From about 1815 the colony, under the governorship of Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; gd, Lachann MacGuaire; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie se ...

, began to grow rapidly as free settlers arrived and new lands were opened up for farming. Despite the long and arduous sea voyage, settlers were attracted by the prospect of making a new life on virtually free Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

land. From the late 1820s settlement was only authorised in the limits of location, known as the Nineteen Counties

The Nineteen Counties were the limits of location in the colony of New South Wales, Australia. Settlers were permitted to take up land only within the counties due to the dangers in the wilderness.

They were defined by the Governor of New Sout ...

.

Many settlers occupied land without authority and beyond these authorised settlement limits: they were known as squatters and became the basis of a powerful landowning class, the Squattocracy. As a result of opposition from the labouring and artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, ...

classes, transportation of convicts to Sydney ended in 1840, although it continued in the smaller colonies of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

(first settled in 1803, later renamed Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

) and Moreton Bay

Moreton Bay is a bay located on the eastern coast of Australia from central Brisbane, Queensland. It is one of Queensland's most important coastal resources. The waters of Moreton Bay are a popular destination for recreational anglers and are ...

(founded 1824, and later renamed Queensland) for a few years more.

The Swan River Settlement

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just Swan River, was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, and it b ...

(as Western Australia was originally known), centred on Perth

Perth is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the Australian states and territories of Australia, state of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth most populous city in Aust ...

, was founded in 1829. The colony suffered from a long-term shortage of labour, and by 1850 local capitalists had succeeded in persuading London to send convicts. (Transportation did not end until 1868.) New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

was part of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

until 1840 when it became a separate colony.

Timeline

*13 May 1787 – The 11 ships of the First Fleet leave Portsmouth under the command of CaptainArthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Greenwich Hospital School from June 1751 unti ...

. Different accounts give varying numbers of passengers but the fleet consisted of at least 1,350 persons of whom 780 were convicts and 570 were free men, women and children and the number included four companies of marines. About 20% of the convicts were women and the oldest convict was 82. About 50% of the convicts had been tried in Middlesex and most of the rest were tried in the county assizes of Devon, Kent and Sussex

*18 January 1788 – The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refe ...

but the landing party was not impressed with the site, and moved the fleet to Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman ...

, landing in Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove ( Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central Sydney loca ...

on 26 January 1788 (now celebrated as Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port J ...

).

*1788 – New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, according to Arthur Phillip's amended Commission dated 25 April 1787, includes "all the islands adjacent in the Pacific Ocean" and running westward to the 135th meridian east. These islands included the current islands of New Zealand, which was administered as part of New South Wales.

* April 1789 – an outbreak of smallpox decimates local tribes.

*1790 – the Second Fleet of convicts arrives in Sydney Cove.

*1791 – Third Fleet of convicts arrives

*1793 – January: the first free settlers arrive in NSW.

*1793 – March–April: visit of the expedition led by Alessandro Malaspina

Alejandro Malaspina (November 5, 1754 – April 9, 1810) was a Tuscan explorer who spent most of his life as a Spanish naval officer. Under a Spanish royal commission, he undertook a voyage around the world from 1786 to 1788, then, from 1789 t ...

.

*1824 - May: Founding of Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

*14 June 1825 – the colony of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

is established in its own right; its name is officially changed to Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

on 1 January 1856. The first settlement was made at Risdon, Tasmania

Risdon is a suburb of Hobart, capital city of Tasmania. It is west of Risdon Vale.

History

It derives its name from Captain William Bellamy Risdon, second officer of the ship ''Duke of Clarence'', which visited the area as part of Sir John Haye ...

on 11 September 1803 when Lt. John Bowen landed with about 50 settlers, crew, soldiers and convicts. The site proved unsuitable and was abandoned in August 1804. Lt.-Col. David Collins finally established a successful settlement at nipaluna on the Country of the Muwinina people and named it Hobart in February 1804 with a party of about 260 people, including 178 convicts. (Collins had previously attempted a settlement in Victoria.) Convict ships were sent from England directly to the colony from 1812 to 1853 and over the 50 years from 1803 to 1853 around 67,000 convicts were transported to Tasmania. About 14,492 were Irish but many of them had been sentenced in English and Scottish courts. Some were also tried locally in other Australian colonies. The ''Indefatigable'' brought the first convicts direct from England on 19 October 1812 and by 1820 there were about 2,500 convicts in the colony. By the end of 1833 the number had increased to 14,900 convicts of whom 1864 were females. About 1,448 held ticket of leave

A ticket of leave was a document of parole issued to convicts who had shown they could now be trusted with some freedoms. Originally the ticket was issued in Britain and later adapted by the United States, Canada, and Ireland.

Jurisdictions ...

, 6,573 were assigned to settlers and 275 were recorded as "absconded or missing". In 1835 there were over 800 convicts working in chain-gangs at the penal station at Port Arthur which operated from 1830 to 1877. Convicts were transferred to Van Diemen's Land from Sydney and, in later years, from 1841 to 1847, from Melbourne. Between 1826 and 1840, there were at least 19 ship loads of convicts sent from Van Diemen's Land to Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together w ...

and at other times they were sent from Norfolk Island to Van Diemen's Land.

*1825 – New South Wales's western border is extended to 129° E.

*21 January 1827 – Western Australia was created when a small British settlement was established at King George's Sound ( Albany) by Major Edmund Lockyer in order to provide a deterrent to the French presence in the area. On 18 June 1829 the new Swan River Colony was officially proclaimed, with Captain James Stirling as the first Governor. Except for the settlement at King George's Sound, the colony was never really a part of NSW. King George's Sound was handed over in 1831. In 1849 the colony was proclaimed a British penal settlement and the first convicts arrived in 1850. Rottnest Island, previously known by the Nyungar name Wadjemup, off the coast of Perth, became the colony's convict settlement in 1838 and was used for local colonial offenders. Around 9,720 British convicts were sent directly to the colony aboard 43 ships between 1850 and 1868. The convicts were sought by local settlers because of the shortage of labour needed to develop the region. On 9 January 1868, Australia's last convict ship, the ''Hougoumont'' brought its final cargo of 269 convicts. Convicts sent to Western Australia were sentenced to terms of 6, 7, 10, 14 and 15 years and some reports suggest that their literacy rate was around 75% as opposed to 50% for those sent to NSW and Tasmania. About a third of the convicts left the Swan River Colony after serving their time. *1835 – the ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'', (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been ''

*1835 – the ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'', (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been ''terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

It was a principle sometimes used in international law to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it.

:

:

...

'' when settled by the British in 1788, and that the Crown had obtained beneficial ownership of all the land of New South Wales from that date. The proclamation stated that British subjects could not obtain title over vacant Crown land directly from Aboriginal Australians, effectively quashing the treaty between John Batman

John Batman (21 January 18016 May 1839) was an Australian grazier, entrepreneur and explorer. He is best known for his role in the founding of Melbourne.

Born and raised in the then-British colony of New South Wales, Batman settled in Van Die ...

and the Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip area.

*28 December 1836 – the British province of

*28 December 1836 – the British province of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

was established. In 1842 it became a crown colony and on 22 July 1861 its area was extended westwards to its present boundary and more area was taken from New South Wales. South Australia was never a British convict colony and between 1836 and 1840 about 13,400 immigrants arrived in the area. Between 1841 and 1850, another 24,900 arrived. Some escaped convicts did settle in the area and no doubt a number of ex-convicts moved there from other colonies. On 4 January 1837 Governor Hindmarsh proclaimed that any offenders convicted in South Australia, and being under sentence of transportation, were to be transported to either New South Wales or Van Diemens Land, by the first opportunity.

*1841 – New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

is separated from New South Wales

*1846 – The colony of North Australia

North Australia can refer to a short-lived former British colony, a former federal territory of the Commonwealth of Australia, or a proposed state which would replace the current Northern Territory.

Colony (1846–1847)

A colony of North Austr ...

was proclaimed by Letters Patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, t ...

on 17 February, which included all of New South Wales north of 26° S. Revoked in December 1846.

European exploration

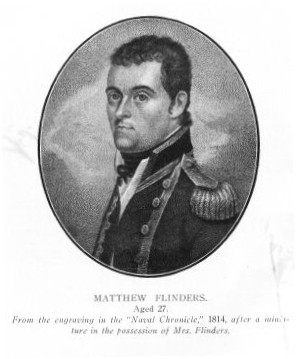

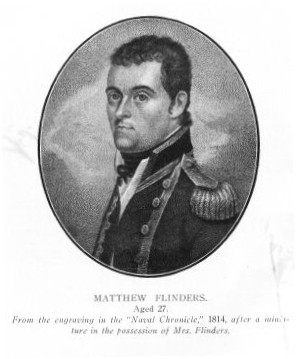

While the actual date of original exploration in Australia is unknown, there is evidence of exploration by William Dampier in 1699, and the First Fleet arrived in 1788, eighteen years after Lt. James Cook surveyed and mapped the entire east coast aboard HM Bark ''Endeavour'' in 1770. In October 1795

While the actual date of original exploration in Australia is unknown, there is evidence of exploration by William Dampier in 1699, and the First Fleet arrived in 1788, eighteen years after Lt. James Cook surveyed and mapped the entire east coast aboard HM Bark ''Endeavour'' in 1770. In October 1795 George Bass

George Bass (; 30 January 1771 – after 5 February 1803) was a British naval surgeon and explorer of Australia.

Early years

Bass was born on 30 January 1771 at Aswarby, a hamlet near Sleaford, Lincolnshire, the son of a tenant farmer, Georg ...

and Matthew Flinders

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was a British navigator and cartographer who led the first littoral zone, inshore circumnavigate, circumnavigation of mainland Australia, then called New Holland ...

, accompanied by William Martin, sailed the boat ''Tom Thumb'' out of Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman ...

to Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refe ...

and explored the Georges River

The Georges River, also known as Tucoerah River, is an intermediate tide-dominated drowned valley estuary, located to the south and west of Sydney, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_ ...

, previously known by the Indigenous name Tucoerah, further upstream than had been done previously by the colonists. Their reports on their return led to the settlement of Banks' Town. In March 1796 the same party embarked on a second voyage in a similar small boat, which they also called the ''Tom Thumb''. During this trip they travelled as far down the coast as Lake Illawarra

Lake Illawarra (Aboriginal Tharawal language: various adaptions of ''Elouera'', ''Eloura'', or ''Allowrie''; ''Illa'', ''Wurra'', or ''Warra'' meaning pleasant place near the sea, or, high place near the sea, or, white clay mountain), is an ope ...

, which they called Tom Thumb Lagoon. They came across and explored Deeban, an estuary occupied by the Tharawal

The Dharawal people, also spelt Tharawal and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people, identified by the Dharawal language. Traditionally, they lived as hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans with ties of kinship, ...

and Eora peoples, and later named Port Hacking

Port Hacking Estuary (Aboriginal Tharawal language: ''Deeban''), an open youthful tide dominated, drowned valley estuary, is located in southern Sydney, New South Wales, Australia approximately south of Sydney central business district. ...

. In 1798–99, Bass and Flinders set out in a sloop and circumnavigated Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

, thus proving it to be an island.

Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in ''The Investigator'' led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Eora man

Aboriginal guides and assistance in the European exploration of the colony were common and often vital to the success of missions. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in ''The Investigator'' led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Eora man Bennelong

Woollarawarre Bennelong ( 1764 – 3 January 1813), also spelt Baneelon, was a senior man of the Eora, an Aboriginal Australian people of the Port Jackson area, at the time of the first British settlement in Australia in 1788. Bennelong ser ...

and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

.

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of early colonial New South Wales.

Throug ...

succeeded in crossing west of Sydney and over the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and sheer cliffs presented by Colomatta, a mountain range on Gundungurra & Dharug

The Dharug or Darug people, formerly known as the Broken Bay tribe, are an Aboriginal Australian people, who share strong ties of kinship and, in pre-colonial times, lived as skilled hunters in family groups or clans, scattered throughout muc ...

Country later named the Blue Mountains, by following the ridges instead of looking for a route through the valleys. At Mount Blaxland

Mount Blaxland, actually a hill, is located about 15 kilometres south of Lithgow. It was the furthest point reached by Blaxland, Lawson, and Wentworth on their historic 1813 crossing of the Blue Mountains.

they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land.

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane

Major General Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet, (23 July 1773 – 27 January 1860), was a British Army officer, administrator, and astronomer. Upon the recommendation of the Duke of Wellington, with whom he had served, he was appoint ...

, commissioned Hamilton Hume and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales's western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell journeyed to the bay Naarm on the land of the Kulin nation, later named Port Phillip, and back. They found many important sites including the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) ( Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longe ...

(which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales and Corio Bay, Victoria.

Charles Sturt

Charles Napier Sturt (28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869) was a British officer and explorer of Australia, and part of the European exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the continent, starting from Sydney and la ...

led an expedition along the Macquarie River in 1828 and found the Darling River

The Darling River (Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka'') is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its conflu

ence with the Murray River at Wentworth, New South Wales. Including its longes ...

. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River

The Murrumbidgee River () is a major tributary of the Murray River within the Murray–Darling basin and the second longest river in Australia. It flows through the Australian state of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, des ...

into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party then followed this river to its junction with the Darling River

The Darling River (Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka'') is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its conflu

ence with the Murray River at Wentworth, New South Wales. Including its longes ...

, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued downriver on to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. Suffering greatly, the party had to then row back upstream hundreds of kilometres for the return journey.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps

The Australian Alps is a mountain range in southeast Australia. It comprises an interim Australian bioregion,0042-5184 However, the moth has also been a biovector of arsenic, transporting it from lowland feeding sites over long distances in ...

in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, Tar-Gan-Gil on the Country of the Ngarigo

The Ngarigo People (also spelt Garego, Ngarego, Ngarago, Ngaragu, Ngarigu, Ngarrugu or Ngarroogoo) are Aboriginal Australian people of southeast New South Wales, whose traditional lands also extend around the present border with Victoria.

Lang ...

people, and he named it Mount Kosciuszko

Mount Kosciuszko ( ; Ngarigo language, Ngarigo: , ), previously spelled Mount Kosciusko, is mainland Australia (continent), Australia's tallest mountain, at 2,228 metres (7,310 ft) above sea level. It is located on the Main Range (Snowy M ...

in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

Aboriginal resistance and accommodation

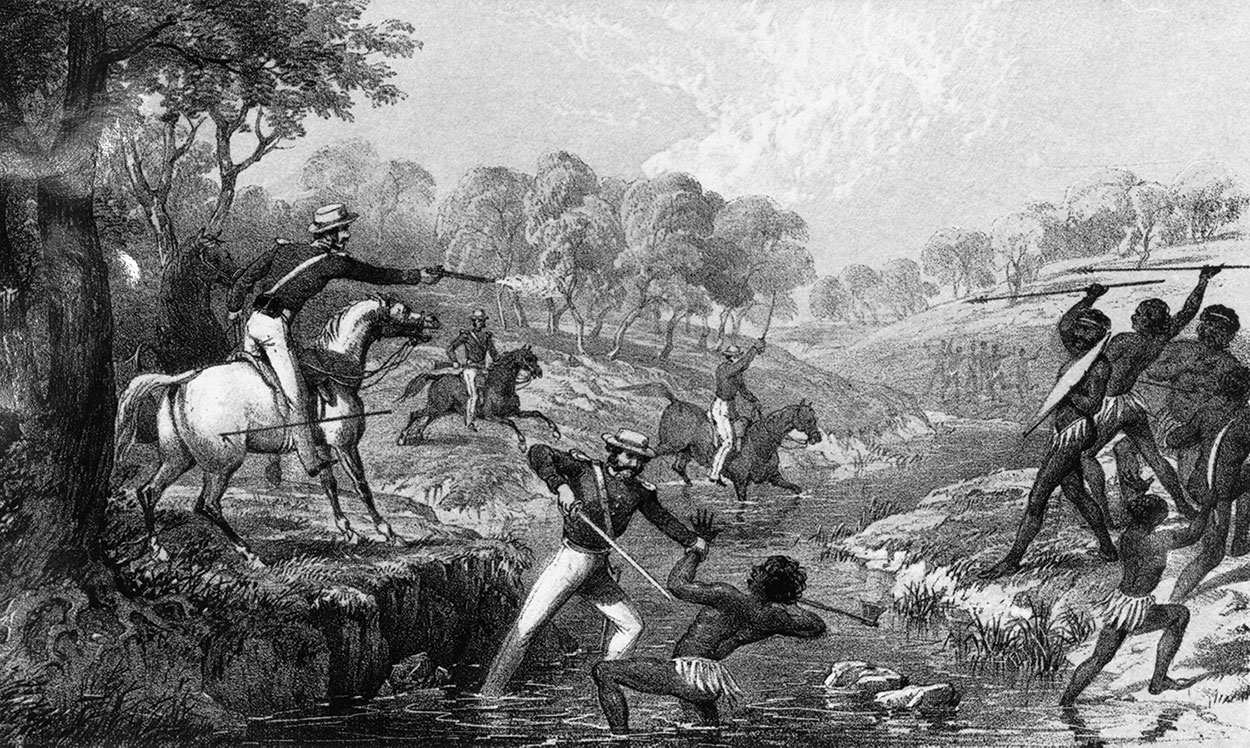

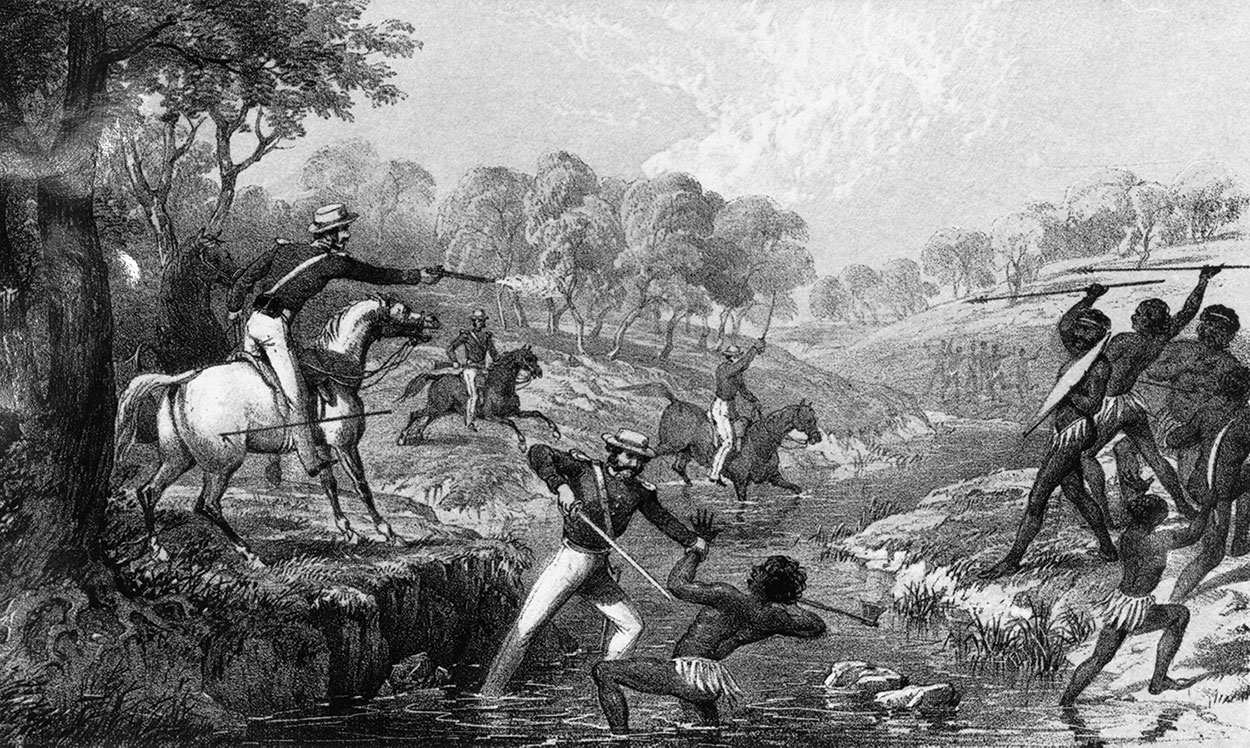

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. European diseases decimated Aboriginal populations, and the occupation of land and degradation of food resources sometimes led to starvation. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits.

According to the historian

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. European diseases decimated Aboriginal populations, and the occupation of land and degradation of food resources sometimes led to starvation. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits.

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator. He is noted for having written authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including '' The Tyranny ...

, in Australia during the colonial period:In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation.Henry Reynolds points out that government officials and ordinary settlers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries frequently used words such as "invasion" and "warfare" to describe their presence and relations with Aboriginal Australians. Reynolds argues that armed resistance by Aboriginal people to white encroachments amounted to

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ...

, beginning in the eighteenth century and continuing into the early twentieth. In the early years of colonisation, David Collins, the senior legal officer in the Sydney settlement, wrote of the local Aboriginal people:While they entertain the idea of our having dispossessed them of their residences, they must always consider us as enemies; and upon this principle they avemade a point of attacking the white people whenever opportunity and safety concurred.In 1847,

Western Australian

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

barrister E.W. Landor stated: "We have seized upon the country, and shot down the inhabitants, until the survivors have found it expedient to submit to our rule. We have acted as Julius Caesar did when he took possession of Britain." In most cases, Reynolds argues, Aboriginal people initially resisted British presence. In a letter to the ''Launceston Advertiser'' in 1831, a settler wrote:We are at war with them: they look upon us as enemies – as invaders – as oppressors and persecutors – they resist our invasion. They have never been subdued, therefore they are not rebellious subjects, but an injured nation, defending in their own way, their rightful possessions which have been torn from them by force.Reynolds quotes numerous writings by settlers who, in the first half of the nineteenth century, described themselves as living in fear due to attacks by Aboriginal people determined to kill them or drive them off their lands. He argues that Aboriginal resistance was, in some cases at least, temporarily effective; the killings of men, sheep and cattle, and burning of white homes and crops, drove some settlers to ruin. Reynolds argues that continuous Aboriginal resistance for well over a century belies the myth of peaceful settlement in Australia. Settlers in turn often reacted to Aboriginal resistance with great violence, resulting in numerous massacres by whites of Aboriginal men, women and children including the Pinjarra massacre, the

Myall Creek massacre

The Myall Creek massacre was the killing of at least twenty-eight unarmed Indigenous Australians by twelve colonists on 10 June 1838 at the Myall Creek near the Gwydir River, in northern New South Wales. After two trials, seven of the twelve ...

, and the Rufus River massacre.

Aboriginal men who resisted British colonisation in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries include Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy (also rendered as Pimbloy, Pemulvoy, Pemulwoy, Pemulwy or Pemulwye, or sometimes by contemporary Europeans as Bimblewove, Bumbleway or Bembulwoyan) (c. 1750 – 2 June 1802) was a Bidjigal man of the Eora nation, born around 1750 in ...

and Yagan. In Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, the "Black War

}

The Black War was a period of violent conflict between British colonists and Aboriginal Tasmanians in Tasmania from the mid-1820s to 1832. The conflict, fought largely as a guerrilla war by both sides, claimed the lives of 600 to 900 Aborigi ...

" was fought in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Accommodation and protection

In the first two years of settlement the Aboriginal people of Sydney, after initial curiosity, mostly avoided the newcomers. In November 1790, 18 months after the smallpox epidemic that had devastated the Aboriginal population,Bennelong

Woollarawarre Bennelong ( 1764 – 3 January 1813), also spelt Baneelon, was a senior man of the Eora, an Aboriginal Australian people of the Port Jackson area, at the time of the first British settlement in Australia in 1788. Bennelong ser ...

led the survivors of several clans into Sydney. Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, joined Matthew Flinders in his circumnavigation of Australia from 1801 to 1803, playing an important role as emissary to the various Indigenous peoples they encountered.

In 1815, Governor Macquarie established a Native Institution to provide elementary education to Aboriginal children, settled 15 Aboriginal families on farms in Sydney and made the first freehold land grant to Aboriginal people at Black Town, west of Sydney. In 1816, he initiated an annual Native Feast at Parramatta which attracted Aboriginal people from as far as the Bathurst plains. However, by the 1820s the Native Institution and Aboriginal farms had failed. Aboriginal people continued to live on vacant waterfront land and on the fringes of the Sydney settlement, adapting traditional practices to the new semi-urban environment.Banivanua Mar, Tracey; Edmonds, Penelope (2013). "Indigenous and settler relations". ''The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I''. p. 344-45