Hindu–German Conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hindu–German Conspiracy (Note on the name) were a series of attempts between 1914 and 1917 by Indian nationalist groups to create a pan-Indian rebellion against the

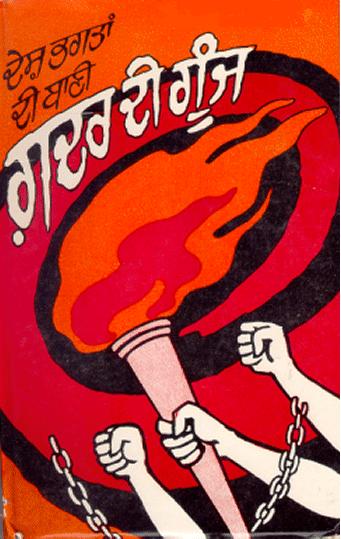

The Ghadar Party, initially the 'Pacific Coast Hindustan Association', was formed in 1913 in the United States under the leadership of

The Ghadar Party, initially the 'Pacific Coast Hindustan Association', was formed in 1913 in the United States under the leadership of

In May 1914, the Canadian government refused to allow the 400 Indian passengers of the ship '' Komagata Maru'' to disembark at

In May 1914, the Canadian government refused to allow the 400 Indian passengers of the ship '' Komagata Maru'' to disembark at

The Indian nationalists then in Paris had, with Egyptian revolutionaries, made plans to assassinate Lord Kitchener as early as 1911, but did not implement them. After the war began, this plan was revived, and Har Dayal's close associate

The Indian nationalists then in Paris had, with Egyptian revolutionaries, made plans to assassinate Lord Kitchener as early as 1911, but did not implement them. After the war began, this plan was revived, and Har Dayal's close associate

In India, unaware of the delayed shipment and confident of being able to rally the Indian

In India, unaware of the delayed shipment and confident of being able to rally the Indian

In April 1915, unaware of the failure of the ''Annie Larsen'' plan, Papen arranged, through

In April 1915, unaware of the failure of the ''Annie Larsen'' plan, Papen arranged, through

The Ghadar Memorial Hall in San Francisco honours members of the party who were hanged following the Lahore conspiracy trial, and the Ghadar Party Memorial Hall in

The Ghadar Memorial Hall in San Francisco honours members of the party who were hanged following the Lahore conspiracy trial, and the Ghadar Party Memorial Hall in

Ireland and India - Colonies, Culture and Empire

"In the Spirit of Ghadar"

''The Tribune'', Chandigarh *.

''

The Hindustan Ghadar Collection

Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Hindu-German Conspiracy Trial on

South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) {{DEFAULTSORT:Hindu-German Conspiracy Indian independence movement British Empire in World War I German Empire in World War I India in World War I Revolutionary movement for Indian independence 1910s in India 1910s in British India Ghadar Party Anushilan Samiti Rabindranath Tagore Hinduism in India Indian-American history South Asian American organizations Germany–India relations India–United States relations Japan–United Kingdom relations United Kingdom–United States relations Cancelled invasions

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. This rebellion was formulated between the Indian revolutionary underground and exiled or self-exiled nationalists in the United States. It also involved the Ghadar Party

The Ghadar Movement or Ghadar Party was an early 20th-century, international political movement founded by expatriate Panjabi s to overthrow British rule in India. Many of the Ghadar Party founders and leaders, including Sohan Singh Bhakna, ...

, and in Germany the Indian independence committee in the decade preceding the Great War. The conspiracy began at the start of the war, with extensive support from the German Foreign Office, the German consulate in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, and some support from Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Euro ...

and the Irish republican movement. The most prominent plan attempted to foment unrest and trigger a Pan-Indian mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

in the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

from Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

to Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

. It was to be executed in February 1915, and overthrow British rule in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

. The February mutiny was ultimately thwarted when British intelligence infiltrated the Ghadarite movement and arrested key figures. Mutinies in smaller units and garrisons within India were also crushed.

The Indo-German alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

and conspiracy were the target of a worldwide British intelligence effort, which successfully prevented further attempts. American intelligence agencies arrested key figures in the aftermath of the ''Annie Larsen'' affair in 1917. The conspiracy resulted in the Lahore conspiracy case trials in India as well as the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial — at the time the longest and most expensive trial ever held in the United States.

This series of events was pivotal for the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

, and became a major factor in reforming the Raj's Indian policy. Similar efforts were made during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Germany and in Japanese-controlled Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

. Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian independence movement, Indian nationalist whose defiance of British raj, British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with ...

formed the Indische Legion and the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA, sometimes Second INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Empire of Japan, Japanese-allied and -supported armed force constituted in Southeast Asia during World War II and led by Indian Nationalism#An ...

, and in Italy Mohammad Iqbal Shedai formed the Battaglione Azad Hindoustan.

Background

Nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

had become more and more prominent in India throughout the last decades of the 19th century as a result of the social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

, economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and political changes instituted in the country through the greater part of the century.

The Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

, founded in 1885, developed as a major platform for loyalists' demands for political liberalization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

Whether and to what ...

and for increased autonomy. The nationalist movement grew with the founding of underground groups in the 1890s. It became particularly strong, radical and violent in Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

and in Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

, along with smaller but nonetheless notable movements in Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

, Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and other places of South India.

In Bengal the revolutionaries more often than not recruited the educated youth of the urban middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

'' Bhadralok'' community that epitomized the "classic" Indian revolutionary, while in Punjab the rural and military society sustained organized violence.

Other related events include:

* the 1915 Singapore Mutiny

The 1915 Singapore Mutiny, (also known as the 1915 Sepoy Mutiny or the Mutiny of the 5th Light Infantry) was a mutiny of elements of the British Indian Army's 5th Light Infantry in British Singapore. Up to half of the regiment, which consi ...

,

* the Annie Larsen arms plot,

* the Jugantar–German plot,

* the German mission to Kabul,

* by some accounts, the Black Tom explosion in 1916.

Parts of the conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

also included efforts to subvert the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 30 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were, on one side, the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers; and on the other side, the British Em ...

.

Indian revolutionary underground

The controversial 1905 partition of Bengal had a widespread political impact. Acting as a stimulus for radical nationalist opinion in India and abroad, it became a focal issue for Indian revolutionaries. Revolutionary organizations like Jugantar and Anushilan Samiti emerged in the 20th century. Significant events took place, including assassinations and attempted assassinations ofcivil servants

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

, prominent public figures and Indian informants, including an attempt in 1907 to kill Bengal Lieutenant-Governor Sir Andrew Fraser. Matters came to a head when the 1912 Delhi–Lahore Conspiracy, led by erstwhile Jugantar member Rash Behari Bose, attempted to assassinate the then-Viceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

, Charles Hardinge. In the aftermath of this event, the British Indian police made concentrated efforts to destroy the Bengali and Punjabi revolutionary underground. Though the movement came under intense pressure for some time, Rash Behari successfully evaded capture for nearly three years. By the time World War I began in 1914, the revolutionary movement had revived in Punjab and Bengal. In Bengal the movement, with a safe haven in the French base of Chandernagore

Chandannagar (), also known by its former names Chandannagore and Chandernagor (), is a city in the Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is headquarter of the Chandannagore subdivision and is a part of the area covered by ...

, had sufficient strength to all but paralyze the state administration.

The earliest mention of a conspiracy for armed revolution in India appears in ''Nixon's Report on Revolutionary Organization'', which reported that Jatin Mukherjee (Bagha Jatin) and Naren Bhattacharya had met with the Crown Prince of Germany during the latter's visit to Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

in 1912, and received assurances that he would receive arms and ammunition At the same time, an increasingly strong pan-Islamic movement began to develop, mainly in the North and North-West regions of India. At the onset of the war in 1914, members of this movement formed an important element of the conspiracy.

At the time of the partition of Bengal, Shyamji Krishna Varma founded India House in London and received extensive support from notable expatriate Indians including Madam Bhikaji Cama, Lala Lajpat Rai

Lala Lajpat Rai (28 January 1865 — 17 November 1928) was an Indian revolutionary, politician, and author, popularly known as ''Punjab Kesari (Lion of Punjab).'' He was one of the three members of the Lal Bal Pal trio. He died of severe tra ...

, S. R. Rana, and Dadabhai Naoroji

Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917), also known as the ''"Grand Old Man of India"'' and "Unofficial Ambassador of India", was an Indian independence activist, political leader, merchant, scholar and writer. He was one of the f ...

. The organization – ostensibly a residence for Indian students – in reality sought to promote nationalist opinion and pro-independence work. India House drew young radical activists like M. L. Dhingra, V. D. Savarkar, V. N. Chatterjee, M. P. T. Acharya and Lala Har Dayal. It developed links with the revolutionary movement in India and nurtured it with arms, funds and propaganda. Authorities in India banned '' The Indian Sociologist'' and other literature published by the House as "seditious". Under V. D. Savarkar's leadership, the House rapidly developed into a centre for intellectual and political activism and a meeting-ground for radical revolutionaries among Indian students in Britain, earning it the moniker "The most dangerous organization outside India" from Valentine Chirol. In 1909 in London M. L. Dhingra fatally shot Sir W. H. Curzon Wyllie, political aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

. In the aftermath of the assassination, the Metropolitan Police and the Home Office

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

rapidly suppressed India House. Its leadership fled to Europe and to the United States. Some, like Chatterjee, moved to Germany; Har Dayal and many others moved to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

Organizations founded in the United States and in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

emulated the example of London's India House. Krishna Varma nurtured close interactions with Turkish and Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

nationalists and with Clan na Gael in the United States. The joint efforts of Mohammed Barkatullah, S. L. Joshi and George Freeman founded the Pan-Aryan Association — modelled after Krishna Varma's Indian Home Rule Society — in New York in 1906. Barkatullah himself had become closely associated with Krishna Varma during a previous stay in London, and his subsequent career in Japan put him at the heart of Indian political activities there. Myron Phelp, an acquaintance of Krishna Varma and an admirer of Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda () (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta, was an Indian Hindus, Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figu ...

, founded an "India House" in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, New York, in January 1908. Amidst a growing Indian student population, erstwhile members of the India House in London succeeded in extending the nationalist work across the Atlantic. The '' Gaelic American'' reprinted articles from the ''Indian Sociologist'', while liberal press-laws allowed free circulation of the ''Indian Sociologist''. Supporters could ship such nationalist literature and pamphlets freely across the world. New York increasingly became an important centre for the Indian movement, such that ''Free Hindustan''— a political revolutionary journal closely mirroring the ''Indian Sociologist'' and the '' Gaelic American'' published by Taraknath Das

Taraknath Das (or Tarak Nath Das; 15 June 1884 – 22 December 1958) was an Indian revolutionary and internationalist scholar. He was a pioneering immigrant in the west coast of North America and discussed his plans with Tolstoy, while organ ...

— moved in 1908 from Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

and Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

to New York. Das established extensive collaboration with the ''Gaelic American'' with help from George Freeman before it was proscribed in 1910 under British diplomatic pressure. This Irish collaboration with Indian revolutionaries led to some of the early but failed efforts to smuggle arms into India, including a 1908 attempt on board a ship called the SS ''Moraitis'' which sailed from New York for the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, before it was searched at Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

. The Irish community later provided valuable intelligence, logistics

Logistics is the part of supply chain management that deals with the efficient forward and reverse flow of goods, services, and related information from the point of origin to the Consumption (economics), point of consumption according to the ...

, communication, media, and legal support to the German, Indian, and Irish conspirators. Those involved in this liaison, and later involved in the plot, included major Irish republicans and Irish-American nationalists like John Devoy

John Devoy (, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican Rebellion, rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 year ...

, Joseph McGarrity, Roger Casement

Roger David Casement (; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during World War I. He worked for the Britis ...

, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

, Father Peter Yorke and Larry de Lacey. These pre-war contacts effectively set up a network which the German foreign office tapped into as war began in Europe.

Ghadar Party

Large-scale Indianimmigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

to the Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

took place in the 20th-century, especially from Punjab, which faced an economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economic downturn that is the result of lowered economic activity in one or more major national economies. It is often understood in economics that economic crisis and the following recession ...

. The Canadian government

The Government of Canada (), formally His Majesty's Government (), is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. The term ''Government of Canada'' refers specifically to the executive, which includes ministers of the Crown ( ...

met this influx with legislation aimed at limiting the entry of South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

ns into Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and at restricting the political rights of those already in the country. The Punjabi community had hitherto been an important loyal force for the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

. The community had expected that its commitment would be honored with the same welcome and rights which the British and colonial governments extended to British and white immigrants. The restrictive legislation fed growing discontent, protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

s and anti-colonial sentiments within the community. Faced with increasingly difficult situations, the community began organizing itself into political groups. Many Punjabis also moved to the United States, but they encountered similar political and social problems.

Meanwhile, India House and nationalist activism of Indian students had begun declining on the east coast of North America towards 1910, but activity gradually shifted west to San Francisco. The arrival at this time of Har Dayal

Lala Rudra Dayal Mathur ( Punjabi: ਲਾਲਾ ਹਰਦਿਆਲ; 14 October 1884 – 4 March 1939) was an Indian nationalist revolutionary and freedom fighter. He was a polymath who turned down a career in the Indian Civil Service. His si ...

from Europe bridged the gap between the intellectual agitators in New York and the predominantly Punjabi labor workers and migrants in the west coast, and laid the foundations of the Ghadar movement

The Ghadar Movement or Ghadar Party was an early 20th-century, international political movement founded by expatriate Panjabi s to overthrow British rule in India. Many of the Ghadar Party founders and leaders, including Sohan Singh Bhakna, wen ...

.

The Ghadar Party, initially the 'Pacific Coast Hindustan Association', was formed in 1913 in the United States under the leadership of

The Ghadar Party, initially the 'Pacific Coast Hindustan Association', was formed in 1913 in the United States under the leadership of Har Dayal

Lala Rudra Dayal Mathur ( Punjabi: ਲਾਲਾ ਹਰਦਿਆਲ; 14 October 1884 – 4 March 1939) was an Indian nationalist revolutionary and freedom fighter. He was a polymath who turned down a career in the Indian Civil Service. His si ...

, with Sohan Singh Bhakna

Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna (4 January 1870 – 20 December 1968) was a Sikh revolutionary, the founding president of the Ghadar Party, and a leading member of the party involved in the Ghadar Conspiracy of 1915. Tried at the Lahore Conspiracy ...

as its president. It drew members from Indian immigrants, largely from Punjab. Many of its members were also from the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkele ...

including Dayal, Tarak Nath Das, Kartar Singh Sarabha and V.G. Pingle. The party quickly gained support from Indian expatriates, especially in the United States, Canada and Asia. Ghadar meetings were held in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

.

Ghadar's ultimate goal was to overthrow British colonial authority in India by means of an armed revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

. It viewed the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

-led mainstream movement for dominion status

A dominion was any of several largely self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of colonial self-governance increased (and, in ...

as modest and its constitutional methods as soft. Ghadar's foremost strategy was to entice Indian soldiers to revolt. To that end, in November 1913 Ghadar established the '' Yugantar Ashram'' press in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. The press produced the '' Hindustan Ghadar'' newspaper and other nationalist literature.

Towards the end of 1913, the party established contact with prominent revolutionaries in India, including Rash Behari Bose. An Indian edition of the '' Hindustan Ghadar'' essentially espoused the philosophies of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

and revolutionary terrorism

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

against British interests in India. Political discontent and violence mounted in Punjab, and Ghadarite publications that reached Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

from California were deemed seditious and banned by the Raj. These events, compounded by evidence of prior Ghadarite incitement in the Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy of 1912, led the British government to pressure the American State Department to suppress Indian revolutionary activities and Ghadarite literature, which emanated mostly from San Francisco.

Germany and the Berlin Committee

With the onset ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, an Indian revolutionary group called the Berlin Committee

The Berlin Committee, later known as the Indian Independence Committee () after 1915, was an organisation formed in Germany in 1914 during World War I by Indian students and political activists residing in the country. The purpose of the committe ...

(later called the Indian Independence Committee) was formed in Germany. Its chief architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

s were C. R. Pillai and V. N. Chatterjee. The committee drew members from Indian students and erstwhile members of the India House including Abhinash Bhattacharya, Dr. Abdul Hafiz, Padmanabhan Pillai, A. R. Pillai, M. P. T. Acharya and Gopal Paranjape. Germany had earlier opened the Intelligence Bureau for the East headed by archaeologist and historian Max von Oppenheim

Baron Max von Oppenheim (15 July 1860 – 17 November 1946) was a German people, German lawyer, diplomat, ancient historian, Panislamism, pan-Islamist and archaeologist. He was a member of the Oppenheim family, Oppenheim banking dynasty. Aban ...

. Oppenheim and Arthur Zimmermann, the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs of the German Empire, actively supported the Berlin committee, which had links with Jatin Mukherjee— a Jugantar Party member and at the time one of the leading revolutionary figures in Bengal. The office of the 25-member committee at No.38 Wielandstrasse was accorded full embassy status.

German Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was chancellor of the German Empire, imperial chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry ...

authorized German activity against British India as World War I broke out in September 1914. Germany decided to actively support the Ghadarite plans. Using the links established between Indian and Irish residents in Germany (including Irish nationalist and poet Roger Casement

Roger David Casement (; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during World War I. He worked for the Britis ...

) and the German Foreign Office, Oppenheim tapped into the Indo-Irish network in the United States. Har Dayal helped organise the Ghadar party before his arrest in the United States in 1914. He jumped bail and made his way to Switzerland, leaving the party and its publications in the charge of Ram Chandra Bharadwaj, who became the Ghadar president in 1914. The German consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth countries, a ...

in San Francisco was tasked to make contact with Ghadar leaders in California. A naval

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operatio ...

lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

by the name of Wilhelm von Brincken with the help of the Indian nationalist journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

Tarak Nath Das and an intermediary by the name of Charles Lattendorf established links with Bharadwaj. Meanwhile, in Switzerland the Berlin committee was able to convince Har Dayal that organising a revolution in India was feasible.

Conspiracy

In May 1914, the Canadian government refused to allow the 400 Indian passengers of the ship '' Komagata Maru'' to disembark at

In May 1914, the Canadian government refused to allow the 400 Indian passengers of the ship '' Komagata Maru'' to disembark at Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

. The voyage had been planned by Gurdit Singh Sandhu as an attempt to circumvent Canadian exclusion laws that effectively prevented Indian immigration. Before the ship reached Vancouver, German radio announced its approach, and British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

n authorities prepared to prevent the passengers from entering Canada. The ship was escorted out of Vancouver by the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

and returned to India.

The incident became a focal point for the Indian community in Canada, which rallied in support of the passengers and against the government's policies. After a two-month legal battle, 24 of the passengers were allowed to immigrate. On reaching Calcutta, the passengers were detained under the Defence of India Act at Budge Budge by the British Indian government, which tried to forcibly transport them to Punjab. This caused rioting at Budge Budge, resulting in fatalities on both sides. Ghadar leaders like Barkatullah and Tarak Nath Das used the inflammatory passions surrounding the ''Komagata Maru'' event as a rallying point and successfully brought many disaffected Indians in North America into the party's fold.

The British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

, meanwhile, contributed significantly to the Allied war effort in World War I. Consequently, a reduced force, an estimated 15,000 troops in late 1914, was stationed in India. It was in this scenario that concrete plans for organising uprisings in India were made.

In September 1913 a Ghadarite named Mathra Singh visited Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

to promote the nationalist cause amongst Indians there, followed by a visit to India in January 1914, when Singh circulated Ghadar literature amongst Indian soldiers through clandestine sources before leaving for Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

. Singh reported that the situation in India was favorable for revolution.

By October 1914, many Ghadarites had returned to India and were assigned tasks like contacting Indian revolutionaries and organizations, spreading propaganda and literature, and arranging to get arms into the country. The first group of 60 Ghadarites led by Jawala Singh left San Francisco for Canton aboard the steamship ''Korea'' on 29 August. They were to sail on to India, where they would be provided with arms to organise a revolt. At Canton, more Indians joined, and the group, now numbering about 150, sailed for Calcutta on a Japanese vessel. They were to be joined by more Ghadarites arriving in smaller groups. During September and October, about 300 Indians left for India in various ships like the SS ''Siberia'', ''Chinyo Maru'', ''China'', ''Manchuria'', '' SS Tenyo Maru'', SS ''Mongolia'' and '' SS Shinyō Maru''. Although the ''Koreas party was uncovered and arrested on their arrival at Calcutta, a successful underground network was established between the United States and India, through Shanghai, Swatow, and Siam

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

. Tehl Singh, the Ghadar operative in Shanghai, is believed to have spent $30,000 on helping revolutionaries to get into India. The Ghadarites in India were able to establish contact with sympathisers in the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

and build networks with underground revolutionary groups.

East Asia

Efforts had begun as early as 1911 to procure arms and smuggle them into India. When a clear idea of the conspiracy emerged, more earnest and elaborate plans were made to obtain arms and to enlist international support. Herambalal Gupta, who had arrived in the United States in 1914 at theBerlin Committee

The Berlin Committee, later known as the Indian Independence Committee () after 1915, was an organisation formed in Germany in 1914 during World War I by Indian students and political activists residing in the country. The purpose of the committe ...

's directive, took over the leadership of American wing of the conspiracy after the failure of the SS ''Korea'' mission. Gupta immediately began efforts to obtain men and arms. While men were in plentiful supply with more and more Indians coming forward to join the Ghadarite cause, obtaining arms for the uprising proved to be more difficult.

The revolutionaries started negotiations with the Chinese government through James Dietrich, who held Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

's power of attorney, to buy a million rifle

A rifle is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting and higher stopping power, with a gun barrel, barrel that has a helical or spiralling pattern of grooves (rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus o ...

s. However, the deal fell through when they realized that the weapons offered were obsolete flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (firearm), ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism its ...

s and muzzle loaders. From China, Gupta went to Japan to try to procure arms and to enlist Japanese support for the Indian independence movement. However, he was forced into hiding within 48 hours when he came to know that the Japanese authorities planned to hand him over to the British. Later reports indicated he was protected at this time by Toyama Mitsuru, right-wing political leader and founder of the Genyosha nationalist secret society.

The Indian Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Thakur (; anglicised as Rabindranath Tagore ; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengalis, Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer, and painter of the Bengal Renai ...

, a strong supporter of Pan-Asianism

file:Asia satellite orthographic.jpg , Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism) is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian people, Asian peo ...

, met Japanese premier Count Terauchi and Count Okuma, a former premier, in an attempt to enlist support for the Ghadarite movement. Tarak Nath Das urged Japan to align with Germany, on the grounds that American war preparation could actually be directed against Japan. Later in 1915, Abani Mukherji

Abaninath Mukherji (, , 3 June 1891 – 28 October 1937) was an Indian communist and émigré based in the Soviet Union who co-founded the Communist Party of India (Tashkent group). His name was often spelt Abani Mukherjee.Banerjee, Santanu,Sta ...

— a Jugantar activist and associate of Rash Behari Bose— is also known to have tried unsuccessfully to arrange for arms from Japan.The ascendancy of Li Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong (; courtesy name ; October 19, 1864 – June 3, 1928) was a prominent Chinese military and political leader during the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China. He was the Provisional Vice President of the Republic of China from 191 ...

to Chinese Presidency in 1916 led to negotiations reopening through his former private secretary, who resided in the United States at the time. In exchange for allowing arms shipments to India through China, China was offered German military assistance and the rights to 10% of any material shipped to India via China. The negotiations were ultimately unsuccessful due to Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

's opposition to an alliance with Germany.

Europe and United States

The Indian nationalists then in Paris had, with Egyptian revolutionaries, made plans to assassinate Lord Kitchener as early as 1911, but did not implement them. After the war began, this plan was revived, and Har Dayal's close associate

The Indian nationalists then in Paris had, with Egyptian revolutionaries, made plans to assassinate Lord Kitchener as early as 1911, but did not implement them. After the war began, this plan was revived, and Har Dayal's close associate Gobind Behari Lal

Gobind Behari Lal was an Indian-American journalist and independence activist. A relative and close associate of Lala Har Dayal, he joined the Ghadar Party and participated in the Indian independence movement. He arrived the United States on a ...

visited Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

in March 1915 from New York to put this plan in action. He may also have intended at this time to bomb the docks in Liverpool. However, these plans ultimately failed. Chattopadhyaya also attempted at this time to revive links with the remnants of India House that survived in London, and through Swiss, German and English sympathisers then resident in Britain. Among them were Meta Brunner (a Swiss woman), Vishna Dube (an Indian man) and his common law German wife Anna Brandt, and Hilda Howsin (an English woman in Yorkshire). Chattopadhyaya's letters were however traced by the censors, leading to the arrest of the cell members. Among other plans that were considered at this time were conspiracies in June 1915 to assassinate Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey and War Minister Lord Kitchener. In addition, they also intended to target French President Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

and Prime Minister René Viviani, King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

and his prime minister Antonio Salandra

Antonio Salandra (; 13 August 1853 – 9 December 1931) was a conservative Italian politician, journalist, and writer who served as the 21st prime minister of Italy between 1914 and 1916. He ensured the entry of Italy in World War I on the side o ...

. These plans were coordinated with the Italian anarchists, with explosives manufactured in Italy. Barkatullah, by now in Europe and working with the Berlin Committee, arranged for these explosives to be sent to the German consulate in Zurich, from where they were expected to be taken charge of by an Italian anarchist named Bertoni. However, British intelligence was able to infiltrate this plot, and successfully pressed Swiss police to expel Abdul Hafiz.

In the United States, an elaborate plan and arrangement was made to ship arms from the country and from the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

through Shanghai, Batavia, Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estim ...

and Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

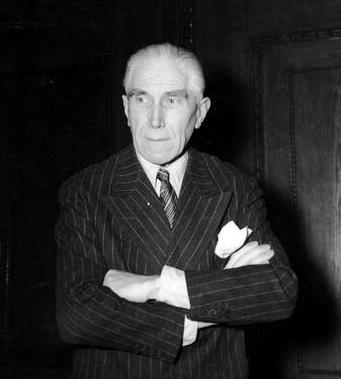

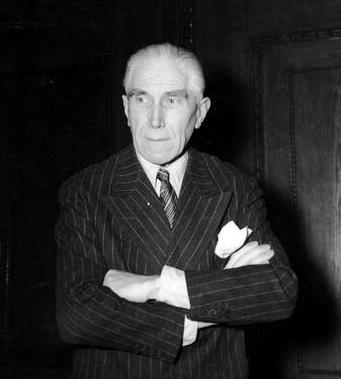

. Even while Herambalal Gupta was on his mission in China and Japan, other plans were explored to ship arms from the United States and East Asia. The German high command decided early on that assistance to the Indian groups would be pointless unless given on a substantial scale. In October 1914, German Vice Consul E.H von Schack in San Francisco approved the arrangements for the funds and armaments. The German military attaché Captain Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and army officer. A national conservative, he served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932, and then as Vice-Chancell ...

acquired $200,000 worth of small arms and ammunition through Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

agents, and arranged for its shipment to India through San Diego, Java, and Burma. The arsenal included 8,080 Springfield rifles of Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

vintage, 2,400 Springfield carbines, 410 Hotchkiss repeating rifle

A repeating rifle is a single-barreled rifle capable of repeated discharges between each ammunition reload. This is typically achieved by having multiple cartridges stored in a magazine (within or attached to the rifle) and then fed individually ...

s, 4,000,000 cartridges, 500 Colt revolvers with 100,000 cartridges, and 250 Mauser pistols along with ammunition. The schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

'' Annie Larsen'' and the sailing ship SS ''Henry S'' were hired to ship the arms out of the United States and transfer it to the . The ownership of ships were hidden under a massive smokescreen involving fake companies and oil business in south-east Asia. For the arms shipment itself, a successful cover was set up to lead British agents to believe that the arms were for the warring factions of the Mexican Civil War. This ruse was successful enough that the rival Villa faction offered $15,000 to divert the shipment to a Villa-controlled port.

Although the shipment was meant to supply the mutiny planned for February 1915, it was not dispatched until June. By then the conspiracy had been uncovered in India, and its major leaders had been arrested or gone into hiding. The shipment itself failed when disastrous co-ordination prevented a successful rendezvous off Socorro Island

Socorro Island () is a volcanic island in the Revillagigedo Islands, a Mexican possession lying off the country's western coast. The size is , with an area of . It is the largest of the four islands of the Revillagigedo Archipelago. The last e ...

with the ''Maverick''. The plot had already been infiltrated by British intelligence through Indian and Irish agents linked closely with the conspiracy. Upon her return to Hoquiam, Washington

Hoquiam ( ) is a city in Grays Harbor County, Washington, Grays Harbor County, Washington (state), Washington, United States. It borders the city of Aberdeen, Washington, Aberdeen at Myrtle Street, with Hoquiam to the west. The two cities share a ...

after several failed attempts, the cargo of the ''Annie Larsen'' was seized by US customs. The cargo was sold at auction despite German Ambassador Count Johann von Bernstoff's attempts to take possession, insisting it was meant for German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

. The Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial opened in 1917 in the United States on charges of gun running and at the time was one of the lengthiest and most expensive trials in American legal history.

Franz von Papen attempted to sabotage rail lines in Canada and destroy the Welland Canal

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, and part of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway. The canal traverses the Niagara Peninsula between Port Weller, Ontario, Port Weller on Lake Ontario, and Port Colborne on Lak ...

. He also

attempted to supply rifles and dynamite to Sikhs in British Columbia for blasting railway bridges. These plots in Canada did not materialise.

Among other events in the United States that have been linked to the conspiracy is the Black Tom explosion when, on the night of 30 July 1916, saboteurs blew up nearly 2 million tons of arms and ammunition at the Black Tom terminal at New York harbour, awaiting shipment in support of the British war effort. Although blamed solely on German agents at the time, later investigations by the Directorate of Naval Intelligence in the aftermath of the ''Annie Larsen'' incident unearthed links between the Black Tom explosion and Franz von Papen, the Irish movement, the Indian movement as well as Communist elements active in the United States.

Pan-Indian mutiny

By the start of 1915, many Ghadarites (nearly 8,000 in the Punjab province alone by some estimates) had returned to India. However, they were not assigned a central leadership and begun their work on an ''ad hoc'' basis. Although some were rounded up by the police on suspicion, many remained at large and began establishing contacts with garrisons in major cities likeLahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

, Ferozepur and Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, third-largest city in the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is a commercial and industrial hub, being the list of cities in P ...

. Various plans had been made to attack the military arsenal at Mian Meer, near Lahore and initiate a general uprising on 15 November 1914. In another plan, a group of Sikh soldiers, the ''manjha jatha'', planned to start a mutiny in the 23rd Cavalry at the Lahore cantonment on 26 November. A further plan called for a mutiny to start on 30 November from Ferozepur under Nidham Singh. In Bengal, the Jugantar, through Jatin Mukherjee, established contacts with the garrison at Fort William in Calcutta. In August 1914, Mukherjee's group had seized a large consignment of guns and ammunition from the Rodda company, a major gun manufacturing firm in India. In December 1914, several politically motivated armed robberies to obtain funds were carried out in Calcutta. Mukherjee kept in touch with Rash Behari Bose through Kartar Singh and V.G. Pingle. These rebellious acts, which were until then organised separately by different groups, were brought into a common umbrella under the leadership of Rash Behari Bose in North India, V. G. Pingle in Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

, and Sachindranath Sanyal in Benares

Varanasi (, also Benares, Banaras ) or Kashi, is a city on the Ganges, Ganges river in North India, northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hinduism, Hindu world.*

*

*

* The city ...

. A plan was made for a unified general uprising, with the date set for 21 February 1915.

February 1915

In India, unaware of the delayed shipment and confident of being able to rally the Indian

In India, unaware of the delayed shipment and confident of being able to rally the Indian sepoy

''Sepoy'' () is a term related to ''sipahi'', denoting professional Indian infantrymen, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire and the Maratha.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its Euro ...

, the plot for the mutiny took its final shape. Under the plans, the 23rd Cavalry in Punjab was to seize weapons and kill their officers while on roll call on 21 February. This was to be followed by mutiny in the 26th Punjab, which was to be the signal for the uprising to begin, resulting in an advance on Delhi and Lahore. The Bengal cell was to look for the ''Punjab Mail'' entering the Howrah Station

Howrah railway station (also known as Howrah Junction) is a railway station located in the city of Howrah, of Kolkata Metropolitan Area, West Bengal, India. It is the largest and busiest railway complex in India, as well as one of the busie ...

the next day (which would have been cancelled if Punjab was seized) and was to strike immediately.

However, Punjab CID successfully infiltrated the conspiracy at the last moment through a sepoy named Kirpal Singh. Sensing that their plans had been compromised, D-Day was brought forward to 19 February, but even these plans found their way to the intelligence. Plans for revolt by the 130th Baluchi Regiment at Rangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

on 21 January were thwarted. Attempted revolts in the 26th Punjab, 7th Rajput, 130th Baluch, 24th Jat Artillery and other regiments were suppressed. Mutinies in Firozpur

Firozpur, (pronunciation: ɪroːzpʊr also known as Ferozepur, is a city on the banks of the Sutlej River in the Firozpur District of Punjab, India. After the Partition of India in 1947, it became a border town on the India–Pakistan bor ...

, Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

, and Agra

Agra ( ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra is the ...

were also suppressed and many key leaders of the conspiracy were arrested, although some managed to escape or evade arrest. A last-ditch attempt was made by Kartar Singh and V. G. Pingle to trigger a mutiny in the 12th Cavalry regiment at Meerut

Meerut (, ISO 15919, ISO: ''Mēraṭh'') is a city in the western region of the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Located in the Meerut district, it is northeast of the national capital, New Delhi, and is ...

. Kartar Singh escaped from Lahore, but was arrested in Varanasi

Varanasi (, also Benares, Banaras ) or Kashi, is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tradition of I ...

, and V. G. Pingle was apprehended in Meerut. Mass arrests followed as the Ghadarites were rounded up in Punjab and the Central Provinces

The Central Provinces was a province of British India. It comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Nagpur was the primary ...

. Rash Behari Bose escaped from Lahore and in May 1915 fled to Japan. Other leaders, including Giani Pritam Singh, Swami Satyananda Puri and others fled to Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

.

On 15 February, the 5th Light Infantry stationed at Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

was among the few units to mutiny successfully. Nearly eight hundred and fifty of its troops mutinied on the afternoon of the 15th, along with nearly a hundred men of the Malay States Guides. This mutiny lasted almost seven days, and resulted in the deaths of 47 British soldiers and local civilians. The mutineers also released the interned crew of the SMS ''Emden'', who were asked by the mutineers to join them but refused and actually took up arms and defended the barracks after the mutineers had left (sheltering some British refugees as well) until the prison camp was relieved. The mutiny was suppressed only after French, Russian and Japanese ships arrived with reinforcements. Of 200 people tried at Singapore, 47 mutineers were shot in public executions, and the rest were transported for life to East Africa, or given jail terms ranging between seven and twenty years. In all, 800 mutineers were either shot, imprisoned or exiled. Some historians, including Hew Strachan, argue that although Ghadar agents operated within the Singapore unit, the mutiny was isolated and not linked to the conspiracy. Others deem this as instigated by the Silk Letter Movement which became intricately related to the Ghadarite conspiracy.

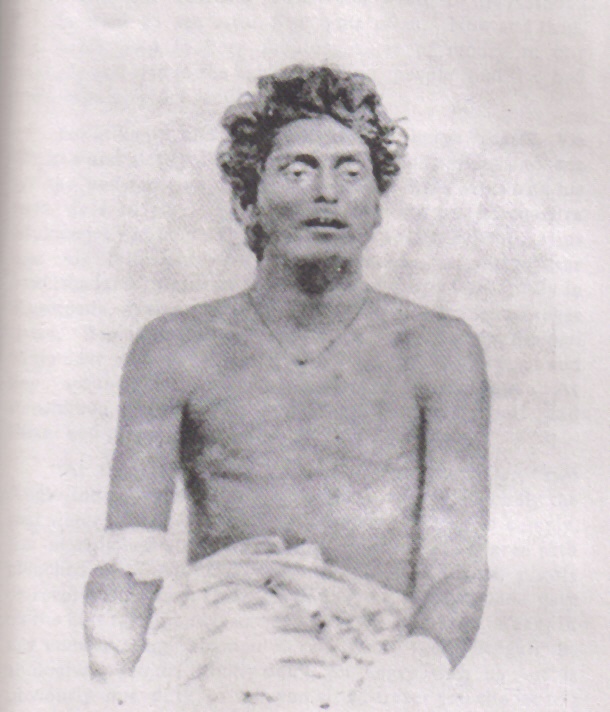

Christmas Day plot

In April 1915, unaware of the failure of the ''Annie Larsen'' plan, Papen arranged, through

In April 1915, unaware of the failure of the ''Annie Larsen'' plan, Papen arranged, through Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

's American representative Hans Tauscher, a second shipment of arms, consisting of 7,300 Springfield rifles, 1,930.3 pistols, ten Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling of North Carolina. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operatio ...

s and nearly 3,000,000 cartridges. The arms were to be shipped in mid June to Surabaya

Surabaya is the capital city of East Java Provinces of Indonesia, province and the List of Indonesian cities by population, second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern corner of Java island, on the Madura Strai ...

in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

on the Holland American steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

''SS Djember''. However, the intelligence network operated by Courtenay Bennett, the Consul General

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

to New York, was able to trace the cargo to Tauscher in New York and passed the information on to the company, thwarting these plans as well. In the meantime, even after the February plot had been scuttled, the plans for an uprising continued in Bengal through the Jugantar cohort under Jatin Mukherjee (Bagha Jatin). German agents in Thailand and Burma, most prominently Emil and Theodor Helferrich— brothers of the German Finance minister Karl Helfferich— established links with Jugantar through Jitendranath Lahiri in March that year. In April, Jatin's chief lieutenant Narendranath Bhattacharya met with the Helfferichs and was informed of the expected arrival of the ''Maverick'' with arms. Although these were originally intended for Ghadar use, the Berlin Committee modified the plans, to have arms shipped into India by the eastern coast of India, through Hatia on the Chittagong

Chittagong ( ), officially Chattogram, (, ) (, or ) is the second-largest city in Bangladesh. Home to the Port of Chittagong, it is the busiest port in Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal. The city is also the business capital of Bangladesh. It ...

coast, Raimangal in the Sundarbans

Sundarbans (; pronounced ) is a mangrove forest area in the Ganges Delta formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers in the Bay of Bengal. It spans the area from the Hooghly River in India's state of West Bengal ...

and Balasore

Balasore, also known as Baleswar, is a city in the state of Odisha, about from the state capital Bhubaneswar and from Kolkata, in eastern India. It is the administrative headquarters of Balasore district and the largest city as well as heal ...

in Orissa

Odisha (), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is a state located in Eastern India. It is the eighth-largest state by area, and the eleventh-largest by population, with over 41 million inhabitants. The state also has the thir ...

, instead of Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

as originally decided. From the coast of the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

, these would be collected by Jatin's group. The date of insurrection was fixed for Christmas Day 1915, earning the name "The Christmas Day Plot". Jatin estimated that he would be able to win over the 14th Rajput Regiment in Calcutta and cut the line to Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

at Balasore and thus take control of Bengal. Jugantar also received funds (estimated to be Rs 33,000 between June and August 1915) from the Helfferich brothers through a fictitious firm in Calcutta. However, it was at this time that the details of the ''Maverick'' and Jugantar plans were leaked to Beckett, the British Consul at Batavia, by a defecting Baltic-German agent under the alias " Oren". The ''Maverick'' was seized, while in India, police destroyed the underground movement in Calcutta as an unaware Jatin proceeded according to plan to the Bay of Bengal coast in Balasore

Balasore, also known as Baleswar, is a city in the state of Odisha, about from the state capital Bhubaneswar and from Kolkata, in eastern India. It is the administrative headquarters of Balasore district and the largest city as well as heal ...

. He was followed there by Indian police and on 9 September 1915, he and a group of five revolutionaries armed with Mauser

Mauser, originally the Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik, was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols was produced beginning in the 1870s for the German armed forces. In the late 19th and ...

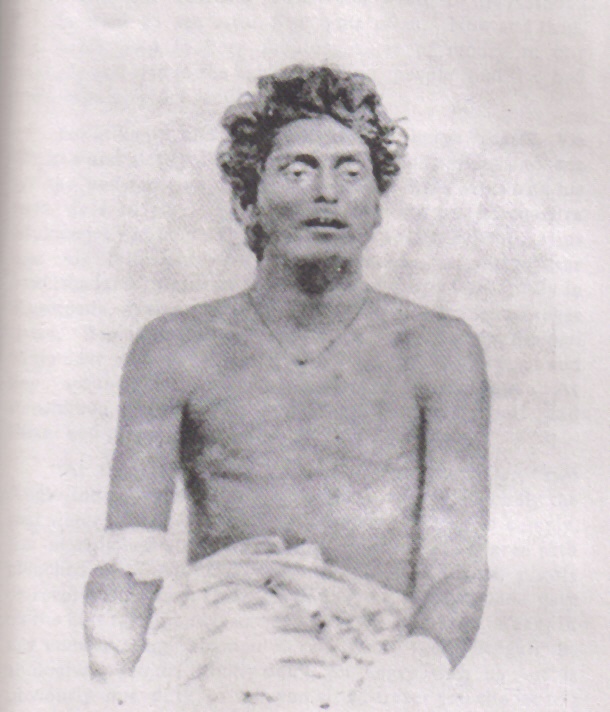

pistols made a last stand on the banks of the river Burhablanga. Seriously wounded in a gun battle that lasted seventy five minutes, Jatin died the next day in Balasore.

To provide the Bengal group enough time to capture Calcutta and to prevent reinforcements from being rushed in, a mutiny coinciding with Jugantar's Christmas Day insurrection was planned for Burma with arms smuggled in from neutral Thailand. Thailand (Siam) was a strong base for the Ghadarites, and plans for rebellion in Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

(which was a part of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

at the time) had been proposed by the Ghadar party as early as October 1914, which called for Burma to be used as a base for subsequent advance into India. This ''Siam-Burma plan'' was finally concluded in January 1915. Ghadarites from branches in China and United States, including Atma Ram, Thakar Singh, and Banta Singh from Shanghai and Santokh Singh and Bhagwan Singh from San Francisco, attempted to infiltrate Burma Military Police in Thailand, which was composed mostly of Sikhs and Punjabi Muslims. Early in 1915, Atma Ram had also visited Calcutta and Punjab and linked up with the revolutionary underground there, including Jugantar. Herambalal Gupta and the German consul at Chicago arranged to have German operatives George Paul Boehm, Henry Schult, and Albert Wehde sent to Siam through Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

with the purpose of training the Indians. Santokh Singh returned to Shanghai tasked to send two expeditions, one to reach the Indian border via Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

and the other to penetrate upper Burma and join with revolutionary elements there. The Germans, while in Manila, also attempted to transfer the arms cargo of two German ships, the ''Sachsen'' and the ''Suevia'', to Siam in a schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

seeking refuge at Manila harbour. However, US customs stopped these attempts. In the meantime, with the help of the German Consul to Thailand Remy, the Ghadarite established a training headquarters in the jungles near the Thai-Burma border for Ghadarites arriving from China and Canada. German Consul General at Shanghai, Knipping, sent three officers of the Peking

Beijing, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's most populous national capital city as well as China's second largest city by urban area after Shanghai. It is l ...

Embassy Guard for training and in addition arranged for a Norwegian agent in Swatow to smuggle arms through. However, the Thai Police high command, which was largely British, discovered these plans and Indian police infiltrated the plot through an Indian secret agent who was revealed the details by the Austrian chargé d'affaires

A (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador. The term is Frenc ...