Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

'' who led an expedition that caused the

fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of what is now mainland Mexico under the rule of the

King of Castile

This is a list of kings regnant and queens regnant of the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom and Crown of Castile. For their predecessors, see List of Castilian counts.

Kings and Queens of Castile

Jiménez dynasty

House of Ivrea / Burgundy

...

in the early 16th century. Cortés was part of the generation of Spanish explorers and conquistadors who began the first phase of the

Spanish colonization of the Americas

The Spanish colonization of the Americas began in 1493 on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) after the initial 1492 voyage of Genoa, Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus under license from Queen Isabella ...

.

Born in

Medellín, Spain, to a family of lesser nobility, Cortés chose to pursue adventure and riches in the

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

. He went to

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

and later to

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, where he received an ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

'' (the right to the labor of certain subjects). For a short time, he served as ''

alcalde

''Alcalde'' (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and Administration (government), administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor (position), corregidor, the presiding officer o ...

'' (magistrate) of the second Spanish town founded on the island. In 1519, he was elected captain of the third expedition to the mainland, which he partly funded. His enmity with the governor of Cuba,

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, resulted in the recall of the expedition at the last moment, an order which Cortés ignored.

Arriving on the continent, Cortés executed a successful strategy of allying with some

indigenous people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

against others. He also used a native woman,

Doña Marina, as an interpreter. She later gave birth to his first son. When the governor of Cuba sent emissaries to arrest Cortés, he fought them and won, using the extra troops as reinforcements.

Cortés wrote letters directly to the king asking to be acknowledged for his successes instead of being punished for mutiny. After he overthrew the

Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

, Cortés was awarded the title of ''

marqués del Valle de Oaxaca'', while the more prestigious title of

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

was given to a high-ranking nobleman,

Antonio de Mendoza

Antonio de Mendoza (1495 – 21 July 1552) was a Spanish colonial administrator who was the first viceroy of New Spain, serving from 14 November 1535 to 25 November 1550, and the second viceroy of Peru, from 23 September 1551, until his d ...

. In 1541 Cortés returned to Spain, where he died six years later of natural causes.

Name

Cortés himself used the form "Hernando" or "Fernando" for his first name, as seen in the contemporary archive documents, his signature and the title of an early portrait.

William Hickling Prescott's ''Conquest of Mexico'' (1843) also refers to him as Hernando Cortés. At some point writers began using the shortened form of "Hernán" more generally.

Physical appearance

In addition to the illustration by the German artist

Christoph Weiditz in his ''Trachtenbuch'', there are three known portraits of Hernán Cortés which were likely made during his lifetime, though only copies of them have survived. All of these portraits show Cortés in the later years of his life.

The account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire written by

Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experienced ...

, gives a detailed description of Hernán Cortés's physical appearance:

Early life

Cortés was born in 1485 in the town of

Medellín

Medellín ( ; or ), officially the Special District of Science, Technology and Innovation of Medellín (), is the List of cities in Colombia, second-largest city in Colombia after Bogotá, and the capital of the department of Antioquia Departme ...

, then a village in the

Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; : ) was a polity in the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. It traces its origins to the 9th-century County of Castile (, ), as an eastern frontier lordship of the Kingdom of León. During the 10th century, the Ca ...

, now a municipality of the modern-day

province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of

Badajoz

Badajoz is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portugal, Portuguese Portugal–Spain border, border, on the left bank of the river ...

in

Extremadura

Extremadura ( ; ; ; ; Fala language, Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is a landlocked autonomous communities in Spain, autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, Spain, Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central- ...

,

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. His father, Martín Cortés de Monroy, born in 1449 to Rodrigo or Ruy Fernández de Monroy and his wife María Cortés, was an infantry captain of distinguished ancestry but slender means. Hernán's mother was Catalína Pizarro Altamirano.

[Machado, J. T. Montalvão, ''Dos Pizarros de Espanha aos de Portugal e Brasil'', Author's Edition, 1st Edition, Lisbon, 1970.]

Through his mother, Hernán was second cousin once removed of

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

, who later

conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

of modern-day Peru (and not to be confused with another Francisco Pizarro, who joined Cortés to conquer the

Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

). Cortés' maternal grandmother, Leonor Sánchez Pizarro Altamirano, was first cousin of Pizarro's father Gonzalo Pizarro y Rodriguez.

Through his father, Hernán was related to

Nicolás de Ovando

Frey Nicolás de Ovando (c. 1460 – 29 May 1511Some sources place his death in 1518.) was a Spanish soldier from a noble family and a Knight of the Order of Alcántara, a military order of Spain. He was Governor of the Indies in the Columbian ...

, the third

governor of Hispaniola. His paternal great-grandfather was

Rodrigo de Monroy y Almaraz, 5th Lord of Monroy.

According to his biographer and chaplain,

Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés was pale and sickly as a child. At the age of 14, he was sent to study Latin under an uncle in Salamanca. Later historians have misconstrued this personal tutoring as time enrolled at the University of Salamanca.

After two years, Cortés returned home to Medellín, much to the irritation of his parents, who had hoped to see him equipped for a profitable legal career. However, those two years in

Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

, plus his long period of training and experience as a notary, first in Valladolid and later in

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

, gave him knowledge of the legal codes of Castile that he applied to help justify his unauthorized conquest of Mexico.

At this point in his life, Cortés was described by Gómara as ruthless, haughty, and mischievous. The 16-year-old youth had returned home to feel constrained by life in his small provincial town. By this time, news of the exciting discoveries of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

in the New World was streaming back to Spain.

Early career in the New World

Plans were made for Cortés to sail to the Americas with a family acquaintance and distant relative,

Nicolás de Ovando

Frey Nicolás de Ovando (c. 1460 – 29 May 1511Some sources place his death in 1518.) was a Spanish soldier from a noble family and a Knight of the Order of Alcántara, a military order of Spain. He was Governor of the Indies in the Columbian ...

, the newly appointed

Governor of Hispaniola. (This island is now divided between

Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

and the

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

). Cortés suffered an injury and was prevented from traveling. He spent the next year wandering the country, probably spending most of his time in Spain's southern ports of

Cadiz,

Palos,

Sanlucar, and

Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

. He finally left for Hispaniola in 1504 and became a colonist.

Arrival

Cortés reached Hispaniola in a ship commanded by Alonso Quintero, who tried to deceive his superiors and reach the New World before them in order to secure personal advantages. Quintero's mutinous conduct may have served as a model for Cortés in his subsequent career.

Upon his arrival in 1504 in

Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo, formerly known as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is the capital and largest city of the Dominican Republic and the List of metropolitan areas in the Caribbean, largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean by population. the Distrito Na ...

, the capital of Hispaniola, the 18-year-old Cortés registered as a citizen; this entitled him to a building plot and land to farm. Soon afterward, Governor Nicolás de Ovando granted him an ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

'' and appointed him as a notary of the town of

Azua de Compostela. His next five years seemed to help establish him in the colony; in 1506, Cortés took part in the conquests of Hispaniola and Cuba. The expedition leader awarded him a large estate of land and

Taíno

The Taíno are the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, Indigenous peoples of the Greater Antilles and surrounding islands. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the principal inhabitants of most of what is now The ...

slaves for his efforts.

Cuba (1511–1519)

In 1511, Cortés accompanied

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide of the Governor of Hispaniola, in his expedition to conquer Cuba. Afterwards Velázquez was appointed

Governor of Cuba. At the age of 26, Cortés was made clerk to the treasurer with the responsibility of ensuring that the Crown received the ''quinto'', or customary one fifth of the profits from the expedition.

Velázquez was so impressed with Cortés that he secured a high political position for him in the colony. He became secretary for Governor Velázquez. Cortés was twice appointed municipal magistrate (''

alcalde

''Alcalde'' (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and Administration (government), administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor (position), corregidor, the presiding officer o ...

'') of

Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

. In Cuba, Cortés became a man of substance with an ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

'' to provide Indian labor for his mines and cattle. This new position of power also made him the new source of leadership, which opposing forces in the colony could then turn to. In 1514, Cortés led a group which demanded that more Indians be assigned to the settlers.

As time went on, relations between Cortés and Governor Velázquez became strained.

[Hassig, Ross. ''Mexico and the Spanish Conquest''. Longman Group UK Limited, 1994, pp. 45–46] Cortés found time to become romantically involved with Catalina Xuárez (or Juárez), the sister-in-law of Governor Velázquez. Part of Velázquez's displeasure seems to have been based on a belief that Cortés was trifling with Catalina's affections. Cortés was temporarily distracted by one of Catalina's sisters but finally married Catalina, reluctantly, under pressure from Governor Velázquez. However, by doing so, he hoped to secure the good will of both her family and that of Velázquez.

It was not until he had been almost 15 years in the Indies that Cortés began to look beyond his substantial status as mayor of the capital of Cuba and as a man of affairs in the thriving colony. He missed the first two expeditions, under the orders of

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and then

Juan de Grijalva, sent by Diego Velázquez to

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

in 1518. News reached Velázquez that

Juan de Grijalva had established a colony on the mainland where there was a bonanza of silver and gold, and Velázquez decided to send him help. Cortés was appointed

captain-general of this new expedition in October 1518, but was advised to move fast before Velázquez changed his mind.

With Cortés's experience as an administrator, knowledge gained from many failed expeditions, and his impeccable rhetoric he was able to gather six ships and 300 men, within a month. Velázquez's jealousy exploded and he decided to put the expedition in other hands. However, Cortés quickly gathered more men and ships in other Cuban ports.

Conquest of Aztec Empire (1519–1521)

In 1518, Velázquez put Cortés in command of an expedition to explore and secure the interior of Mexico for colonization. At the last minute, due to the old argument between the two, Velázquez changed his mind and revoked Cortés's charter. Cortés ignored the orders and, in an act of open

mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

, went anyway in February 1519. He stopped in

Trinidad, Cuba, to hire more soldiers and obtain more horses. Accompanied by about 11 ships, 500 men (including seasoned slaves), 13 horses, and a small number of

cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

, Cortés landed on the

Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

in

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

territory.

[Bernard Grunberg, ''"La folle aventure d'Hernan Cortés''", in '']L'Histoire

''L'Histoire'' is a monthly mainstream French magazine dedicated to historical studies, recognized by peers as the most important historical popular magazine (as opposed to specific university journals or less scientific popular historical magaz ...

'' n° 322, July–August 2007 There he encountered

Geronimo de Aguilar, a Spanish

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

priest who had survived a

shipwreck

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. It results from the event of ''shipwrecking'', which may be intentional or unintentional. There were approximately thre ...

followed by a period in captivity with the

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

, before escaping.

Aguilar had learned the

Chontal Maya language and was able to translate for Cortés.

[Crowe, John A. The Epic of Latin America. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1992. 4th ed. p. 75]

Cortés's military experience was almost nonexistent, but he proved to be an effective leader of his small army and won early victories over the coastal Indians. In March 1519, Cortés formally claimed the land for the

Spanish crown

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

. Then he proceeded to

Tabasco

Tabasco, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tabasco, is one of the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Tabasco, 17 municipalities and its capital city is Villahermosa.

It i ...

, where he met with resistance and won a

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

against the natives. He received twenty young indigenous women from the vanquished natives, and he converted them all to Christianity.

Among these women was

La Malinche, his future

mistress and mother of his son

Martín.

Malinche knew both the

Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

language and Chontal Maya, thus enabling Cortés to communicate with the Aztecs through Aguilar.

[Diaz, B. (1963), ''The Conquest of New Spain'', London: Penguin Books, ] At

San Juan de Ulúa

San Juan de Ulúa, now known as Castle of San Juan de Ulúa, is a large complex of fortresses, prisons and one former palace on an island of the same name in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the seaport of Veracruz, Mexico. Juan de Grijalva' ...

on

Easter Sunday

Easter, also called Pascha (Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek language, Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, de ...

1519, Cortés met with

Moctezuma II

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin . ( – 29 June 1520), retroactively referred to in European sources as Moctezuma II, and often simply called Montezuma,Other variant spellings include Moctezuma, Motewksomah, Motecuhzomatzin, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma, Motē ...

's

Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

governors Tendile and Pitalpitoque.

In July 1519, his men took over

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

. By this act, Cortés dismissed the authority of the governor of Cuba to place himself directly under the orders of

King Charles.

To eliminate any ideas of retreat, Cortés

scuttled his ships.

[Hassig, Ross. ''Mexico and the Spanish Conquest''. Longman Group UK Limited, 1994, pp. 53–54]

March on Tenochtitlán

In Veracruz, he met some of the tributaries of the Aztecs and asked them to arrange a meeting with

Moctezuma II

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin . ( – 29 June 1520), retroactively referred to in European sources as Moctezuma II, and often simply called Montezuma,Other variant spellings include Moctezuma, Motewksomah, Motecuhzomatzin, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma, Motē ...

, the ''

tlatoani

''Tlahtoāni'' ( , "ruler, sovereign"; plural ' ) is a historical title used by the dynastic rulers of (singular ''āltepētl'', often translated into English as "city-state"), autonomous political entities formed by many pre-Columbian Nahuatl- ...

'' (ruler) of the Aztec Empire.

Moctezuma repeatedly turned down the meeting, but Cortés was determined. Leaving a hundred men in Veracruz, Cortés marched on

Tenochtitlán in mid-August 1519, along with 600 soldiers, 15 horsemen, 15

cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

s, and hundreds of indigenous carriers and warriors.

On the way to Tenochtitlán, Cortés made alliances with

indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

such as the

Totonac

The Totonac are an Indigenous people of Mexico who reside in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, and Hidalgo. They are one of the possible builders of the pre-Columbian city of El Tajín, and further maintained quarters in Teotihuacán (a cit ...

s of

Cempoala and the

Nahuas

The Nahuas ( ) are a Uto-Nahuan ethnicity and one of the Indigenous people of Mexico, with Nahua minorities also in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. They comprise the largest Indigenous group in Mexico, as well as ...

of

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala, is one of the 32 federal entities that comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Tlaxcala, 60 municipalities and t ...

. The

Otomis initially, and then the

Tlaxcalans clashed with the Spanish in a series of three battles from 2 to 5 September 1519, and at one point, Diaz remarked, "they surrounded us on every side". After Cortés continued to release prisoners with messages of peace, and realizing the Spanish were enemies of Moctezuma,

Xicotencatl the Elder and

Maxixcatzin persuaded the Tlaxcalan warleader,

Xicotencatl the Younger, that it would be better to ally with the newcomers than to kill them.

In October 1519, Cortés and his men, accompanied by about 1,000 Tlaxcalteca,

marched to

Cholula, the second-largest city in central Mexico. Cortés, either in a pre-meditated effort to instill fear upon the Aztecs waiting for him at Tenochtitlan or (as he later claimed, when he was being investigated) wishing to make an example when he feared native treachery, massacred thousands of unarmed members of the nobility gathered at the central plaza, then partially burned the city.

By the time he arrived in Tenochtitlán, the Spaniards had a large army. On November 8, 1519, they were peacefully received by Moctezuma II. Moctezuma deliberately let Cortés enter the Aztec capital, the island city of Tenochtitlán, hoping to get to know their weaknesses better and to crush them later.

Moctezuma gave lavish gifts of gold to the Spaniards which, rather than placating them, excited their ambitions for plunder. In his letters to King Charles, Cortés claimed to have learned at this point that he was considered by the Aztecs to be either an emissary of the feathered serpent god

Quetzalcoatl or Quetzalcoatl himself—a belief which has been contested by a few modern historians. But quickly Cortés learned that several Spaniards on the coast had been killed by Aztecs while supporting the Totonacs, and decided to take Moctezuma as a hostage in his palace, indirectly ruling Tenochtitlán through him.

Meanwhile, Velázquez sent another expedition, led by

Pánfilo de Narváez, to oppose Cortés, arriving in Mexico in April 1520 with 1,100 men.

Cortés left 200 men in Tenochtitlán and took the rest to confront Narváez. He overcame Narváez, despite his numerical inferiority, and convinced the rest of Narváez's men to join him.

In Mexico, one of Cortés's lieutenants

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, ''conquistador'', ''adelantado,'' governor and Captaincy General of Guatemala, captain general of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the c ...

, committed the ''

massacre in the Great Temple'', triggering a local rebellion.

Cortés speedily returned to Tenochtitlán. On July 1, 1520, Moctezuma was killed (he was stoned to death by his own people, as reported in Spanish accounts; although some claim he was murdered by the Spaniards once they realized his inability to placate the locals). Faced with a hostile population, Cortés decided to flee for Tlaxcala. During the ''

Noche Triste'' (June 30 – July 1, 1520), the Spaniards managed a narrow escape from Tenochtitlán across the Tlacopan causeway, while their rearguard was being massacred. Much of the treasure looted by Cortés was lost (as well as his artillery) during this panicked escape from Tenochtitlán.

Destruction of Tenochtitlán

After

a battle in Otumba, they managed to reach Tlaxcala, having lost 870 men.

With the assistance of their allies, Cortés's men finally prevailed with reinforcements arriving from

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. Cortés began a policy of

attrition towards Tenochtitlán, cutting off supplies and subduing the Aztecs' allied cities. During the siege he would construct

brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

s in the lake and slowly destroy blocks of the city to avoid fighting in an urban setting. The Mexicas would fall back to

Tlatelolco and even succeed in ambushing the pursuing Spanish forces, inflicting heavy losses, but would ultimately be the last portion of the island that resisted the conquistadores. The

siege of Tenochtitlan ended with Spanish victory and the destruction of the city.

In January 1521, Cortés countered a conspiracy against him, headed by Antonio de Villafana, who was hanged for the offense.

Finally, with the capture of

Cuauhtémoc

Cuauhtémoc (, ), also known as Cuauhtemotzín, Guatimozín, or Guatémoc, was the Aztec ruler ('' tlatoani'') of Tenochtitlan from 1520 to 1521, and the last Aztec Emperor. The name Cuauhtemōc means "one who has descended like an eagle", an ...

, the ''

tlatoani

''Tlahtoāni'' ( , "ruler, sovereign"; plural ' ) is a historical title used by the dynastic rulers of (singular ''āltepētl'', often translated into English as "city-state"), autonomous political entities formed by many pre-Columbian Nahuatl- ...

'' (ruler) of Tenochtitlán, on August 13, 1521, the Aztec Empire was captured, and Cortés was able to claim it for Spain, thus renaming the city

Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. From 1521 to 1524, Cortés personally governed Mexico.

Appointment to governorship of New Spain and internal dissensions

Many historical sources have conveyed an impression that Cortés was unjustly treated by the

Spanish Crown

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

, and that he received nothing but ingratitude for his role in establishing

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

. This picture is the one Cortés presents in his letters and in the later biography written by

Francisco López de Gómara. However, there may be more to the picture than this. Cortés's own sense of accomplishment, entitlement, and vanity may have played a part in his deteriorating position with the king:

King Charles appointed Cortés as governor, captain general and chief justice of the newly conquered territory, dubbed "

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

of the Ocean Sea". But also, much to the dismay of Cortés, four royal officials were appointed at the same time to assist him in his governing—in effect, submitting him to close observation and administration. Cortés initiated the construction of

Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

, destroying Aztec temples and buildings and then rebuilding on the Aztec ruins what soon became the most important European city in the Americas.

Cortés managed the founding of new cities and appointed men to extend Spanish rule to all of New Spain, imposing the ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

'' system in 1524.

He reserved many encomiendas for himself and for his retinue, which they considered just rewards for their accomplishment in conquering central Mexico. However, later arrivals and members of factions antipathetic to Cortés complained of the favoritism that excluded them.

In 1523, the Crown (possibly influenced by Cortés's enemy,

Bishop Fonseca), sent a military force under the command of

Francisco de Garay

Francisco de Garay (1475 in Sopuerta, Biscay – 1523) was a Spanish Basque people, Basque conquistador.

Early life

Garay was born in the Garay tower in Sopuerta, in the county of Encartaciones located in the province of Biscay. He was a companio ...

to conquer and settle the northern part of Mexico, the region of

Pánuco. This was another setback for Cortés who mentioned this in his fourth letter to the King in which he describes himself as the victim of a conspiracy by his archenemies

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar,

Diego Columbus and Bishop Fonseca as well as Francisco Garay. The influence of Garay was effectively stopped by this appeal to the King who sent out a decree forbidding Garay to interfere in the politics of New Spain, causing him to give up without a fight.

Royal grant of arms (1525)

Although Cortés had flouted the authority of Diego Velázquez in sailing to the mainland and then leading an expedition of conquest, Cortés's spectacular success was rewarded by the crown with a coat of arms, a mark of high honor, following the conqueror's request. The document granting the coat of arms summarizes Cortés's accomplishments in the conquest of Mexico. The proclamation of the king says in part:

We, respecting the many labors, dangers, and adventures which you underwent as stated above, and so that there might remain a perpetual memorial of you and your services and that you and your descendants might be more fully honored ... it is our will that besides your coat of arms of your lineage, which you have, you may have and bear as your coat of arms, known and recognized, a shield ...["Grant of coat of arms to Hernando Cortés, 1525" transcription and translation by J. Benedict Warren. ''The Harkness Collection in the Library of Congress: Manuscripts concerning Mexico''. Washington DC: Library of Congress 1974.]

The grant specifies the iconography of the coat of arms, the central portion divided into quadrants. In the upper portion, there is a "black eagle with two heads on a white field, which are the arms of the empire".

Below that is a "golden lion on a red field, in memory of the fact that you, the said Hernando Cortés, by your industry and effort brought matters to the state described above" (i.e., the conquest).

The specificity of the other two quadrants is linked directly to Mexico, with one quadrant showing three crowns representing the three Aztec emperors of the conquest era,

Moctezuma,

Cuitlahuac, and

Cuauhtemoc and the other showing the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

Encircling the central shield are symbols of the seven city-states around the lake and their lords that Cortés defeated, with the lords "to be shown as prisoners bound with a chain which shall be closed with a lock beneath the shield".

Death of his first wife and remarriage

Cortés's wife Catalina Súarez arrived in New Spain around summer 1522, along with her sister and brother. His marriage to Catalina was at this point extremely awkward, since she was a kinswoman of the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, whose authority Cortés had thrown off and who was therefore now his enemy. Catalina lacked the noble title of ''doña,'' so at this point his marriage with her no longer raised his status. Their marriage had been childless. Since Cortés had sired children with a variety of indigenous women, including a son around 1522 by his cultural translator,

Doña Marina, Cortés knew he was capable of fathering children. Cortés's only male heir at this point was illegitimate, but nonetheless named after Cortés's father, Martín Cortés. This son

Martín Cortés was also popularly called "El Mestizo".

Catalina Suárez died under mysterious circumstances the night of November 1–2, 1522. There were accusations at the time that Cortés had murdered his wife.

There was an investigation into her death, interviewing a variety of household residents and others. The documentation of the investigation was published in the nineteenth century in Mexico and these archival documents were uncovered in the twentieth century. The death of Catalina Suárez produced a scandal and investigation, but Cortés was now free to marry someone of high status more appropriate to his wealth and power. In 1526, he built an imposing residence for himself, the

Palace of Cortés in

Cuernavaca

Cuernavaca (; , "near the woods" , Otomi language, Otomi: ) is the capital and largest city of the Mexican state, state of Morelos in Mexico. Along with Chalcatzingo, it is likely one of the origins of the Mesoamerica, Mesoamerican civilizatio ...

, in a region close to the capital where he had extensive

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

holdings. In 1529 he had been accorded the noble designation of ''

don'', but more importantly was given the noble title of Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca and married the Spanish noblewoman Doña Juana de Zúñiga. The marriage produced three children, including another son, who was also named Martín. As the first-born legitimate son, Don

Martín Cortés y Zúñiga was now Cortés's heir and succeeded him as holder of the title and estate of the

Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca. Cortés's legitimate daughters were Doña Maria, Doña Catalina, and Doña Juana.

Cortés and the "Spiritual Conquest" of the Aztec Empire

Since the conversion to Christianity of indigenous peoples was an essential and integral part of the extension of Spanish power, making formal provisions for that conversion once the military conquest was completed was an important task for Cortés. During the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

, the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

had seen early attempts at conversion in the Caribbean islands by Spanish friars, particularly the mendicant orders. Cortés made a request to the Spanish monarch to send

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

and

Dominican friars to Mexico to convert the vast indigenous populations to Christianity. In his fourth letter to the king, Cortés pleaded for friars rather than diocesan or secular priests because those clerics were in his view a serious danger to the Indians' conversion.

If these people ndianswere now to see the affairs of the Church and the service of God in the hands of canons or other dignitaries, and saw them indulge in the vices and profanities now common in Spain, knowing that such men were the ministers of God, it would bring our Faith into much harm that I believe any further preaching would be of no avail.

He wished the mendicants to be the main evangelists. Mendicant friars did not usually have full priestly powers to perform all the sacraments needed for conversion of the Indians and growth of the neophytes in the Christian faith, so Cortés laid out a solution to this to the king.

Your Majesty should likewise beseech His Holiness he popeto grant these powers to the two principal persons in the religious orders that are to come here, and that they should be his delegates, one from the Order of St. Francis and the other from the Order of St. Dominic. They should bring the most extensive powers Your Majesty is able to obtain, for, because these lands are so far from the Church of Rome, and we, the Christians who now reside here and shall do so in the future, are so far from the proper remedies of our consciences and, as we are human, so subject to sin, it is essential that His Holiness should be generous with us and grant to these persons most extensive powers, to be handed down to persons actually in residence here whether it be given to the general of each order or to his provincials.

The Franciscans arrived in May 1524, a symbolically powerful group of twelve known as the

Twelve Apostles of Mexico, led by Fray

Martín de Valencia. Franciscan

Geronimo de Mendieta claimed that Cortés's most important deed was the way he met this first group of Franciscans. The conqueror himself was said to have met the friars as they approached the capital, kneeling at the feet of the friars who had walked from the coast. This story was told by Franciscans to demonstrate Cortés piety and humility and was a powerful message to all, including the Indians, that Cortés's earthly power was subordinate to the spiritual power of the friars. However, one of the first twelve Franciscans, Fray

Toribio de Benavente Motolinia does not mention it in his history. Cortés and the Franciscans had a particularly strong alliance in Mexico, with Franciscans seeing him as "the new Moses" for conquering Mexico and opening it to Christian evangelization. In Motolinia's 1555 response to Dominican

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ); 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a Spanish clergyman, writer, and activist best known for his work as an historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman, then became ...

, he praises Cortés.

And as to those who murmur against the Marqués del Valle ortés God rest him, and who try to blacken and obscure his deeds, I believe that before God their deeds are not as acceptable as those of the Marqués. Although as a human he was a sinner, he had faith and works of a good Christian, and a great desire to employ his life and property in widening and augmenting the fair of Jesus Christ, and dying for the conversion of these gentiles ... Who has loved and defended the Indians of this new world like Cortés? ... Through this captain, God opened the door for us to preach his holy gospel and it was he who caused the Indians to revere the holy sacraments and respect the ministers of the church.

In Fray

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún ( – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he jour ...

's 1585 revision of the conquest narrative first codified as Book XII of the

Florentine Codex, there are laudatory references to Cortés that do not appear in the earlier text from the indigenous perspective. Whereas Book XII of the Florentine Codex concludes with an account of Spaniards' search for gold, in Sahagún's 1585 revised account, he ends with praise of Cortés for requesting the Franciscans be sent to Mexico to convert the Indians.

Expedition to Honduras and aftermath (1524–1541)

Expedition to Honduras (1524–1526)

From 1524 to 1526, Cortés headed an expedition to

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

where he defeated

Cristóbal de Olid

Cristóbal de Olid (; 1487–1524) was a Spanish adventurer, conquistador and rebel who played a part in the conquest of the Aztec Empire and present-day Honduras.

Born in Baeza, Olid grew up in the household of the governor of Cuba, Diego V ...

, who had claimed Honduras as his own under the influence of the Governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez. Fearing that

Cuauhtémoc

Cuauhtémoc (, ), also known as Cuauhtemotzín, Guatimozín, or Guatémoc, was the Aztec ruler ('' tlatoani'') of Tenochtitlan from 1520 to 1521, and the last Aztec Emperor. The name Cuauhtemōc means "one who has descended like an eagle", an ...

might head an insurrection in Mexico, he brought him with him to Honduras. In a controversial move, Cuauhtémoc was executed during the journey. Raging over Olid's treason, Cortés issued a decree to arrest Velázquez, whom he was sure was behind Olid's actions. This, however, only served to further estrange the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Castile, Castile and Kingd ...

and the

Council of the Indies

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

, both of which were already beginning to feel anxious about Cortés's rising power.

Cortés's fifth letter to King Charles attempts to justify his conduct, concludes with a bitter attack on "various and powerful rivals and enemies" who have "obscured the eyes of your Majesty". Charles, who was also

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, had little time for distant colonies (much of Charles's reign was taken up with

wars with France, the

German Protestants

Protestantism (), a branch of Christianity, was founded within Germany in the 16th-century Reformation. It was formed as a new direction from some Roman Catholic principles. It was led initially by Martin Luther and later by John Calvin.

Histor ...

and the expanding

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

), except insofar as they contributed to finance his wars. In 1521, year of the Conquest, Charles was attending to matters in his German domains and Bishop

Adrian of Utrecht functioned as regent in Spain.

Velázquez and Fonseca persuaded the regent to appoint a commissioner (a ''

Juez de residencia'',

Luis Ponce de León) with powers to investigate Cortés's conduct and even arrest him. Cortés was once quoted as saying that it was "more difficult to contend against

isown countrymen than against the Aztecs." Governor Diego Velázquez continued to be a thorn in his side, teaming up with Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, chief of the Spanish colonial department, to undermine him in the Council of the Indies.

Before leaving for Honduras, on October 12, 1524, Cortés had left in charge three of the five officials that made up the ''

Tribunal de Cuentas'' set up by Charles V to oversee Cortés' rule:

Alonso de Estrada;

Rodrigo de Albornoz; and

Alonso de Zuazo. The other two

Gonzalo de Salazar and

Pedro Almíndez Chirino (aka 'Peralmíndez'), accompanied him on campaign.

While en route, word reached Cortes that disagreements between Albornoz and Estrada were becoming violent to the point of swordplay. He therefore ordered Salazar and Almíndez Chirino back to Mexico City to rejoin the government, which they did on December 29, 1524.

Salazar and Almíndez Chirino spread a rumour that Cortés had died, and in May 1525 assumed all power for themselves, including seizing Cortés property and torturing his majordomo, Cortés' cousin, Rodrigo de Paz, to reveal the whereabouts of his alleged treasure.

Zuazo was forced into exile.

At the end of January 1526, Cortés got a message back to his supporters that he was still alive. Salazar and Almíndez Chirino were deposed and arrested, and Albornoz and Estrada resumed office. Cortes himself took another five months to return from his expedition, reaching Mexico City on 19 June, whereupon he rested up in the Franciscan monastery for 5 nights.

A day or so later, Ponce de León finally arrived in Mexico City to take over from Cortés as governor of New Spain and begin the

juez de residencia. The Licentiate then fell ill and died shortly after his arrival, appointing

Marcos de Aguilar as ''alcalde mayor''. In February 1527, the aged Aguilar fell ill in his turn and before his death, appointed

Alonso de Estrada to the position of governor, in which function he was confirmed by royal decree in August 1527. Cortés, suspected of poisoning the two men, refrained from taking over the government.

Albornoz, who had sailed for Spain shortly after Ponce de León's arrival in 1526, persuaded the Council of the Indies on his arrival in Seville to release Salazar and Almíndez Chirino, against Cortés' wishes.

In August 1527, Estrada was confirmed as governor by royal decree. When Cortés protested to Estrada for having one of his adherents' hands cut off without a trial as punishment for his involvement in a brawl, Estrada ordered Cortés exiled to his country estate.

His authority circumscribed, his persecutors unpunished, while yet his retinue suffered from arbitrary punishments and exiled from the city he'd founded, Cortés sailed for Spain in early 1528 to appeal to his Emperor, Charles V.

First return to Spain (1528) and Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca

In May 1528, Cortés arrived in Spain with treasures and 40 Aztecs to impress and to appeal to the justice of his master, Charles V. Juan Altamirano and

Alonso Valiente stayed in Mexico and acted as Cortés's representatives during his absence. Cortés presented himself with great splendor before Charles V's court. By this time Charles had returned and Cortés forthrightly responded to his enemy's charges. Denying he had held back on gold due the crown, he showed that he had contributed more than the quinto (one-fifth) required. Indeed, he had spent lavishly to build the new capital of Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, leveled during the siege that brought down the Aztec empire.

He was received by Charles with every distinction, and decorated with the

order of Santiago

The Order of Santiago (; ) is a religious and military order founded in the 12th century. It owes its name to the patron saint of Spain, ''Santiago'' ( St. James the Greater). Its initial objective was to protect the pilgrims on the Way of S ...

. In return for his efforts in expanding the still young

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

, Cortés was rewarded in 1529 by being accorded the noble title of ''

don'' but more importantly named the ''"Marqués del Valle de

Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

"'' (

Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca) and married the Spanish noblewoman Doña Juana Zúñiga, after the 1522 death of his much less distinguished first wife, Catalina Suárez. The noble title and senorial estate of the Marquesado was passed down to his descendants until 1811. The Oaxaca Valley was one of the wealthiest regions of New Spain, and Cortés had 23,000

vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s in 23 named

encomiendas in perpetuity.

Although confirmed in his land holdings and vassals, he was not reinstated as governor and was never again given any important office in the administration of New Spain. During his travel to Spain, his property was mismanaged by abusive colonial administrators. He sided with local natives in a lawsuit. The natives documented the abuses in the

Huexotzinco Codex.

The entailed estate and title passed to his legitimate son Don

Martín Cortés upon Cortés's death in 1547, who became the Second Marquess. Don Martín's association with the so-called Encomenderos' Conspiracy endangered the entailed holdings, but they were restored and remained the continuing reward for Hernán Cortés's family through the generations.

Return to the New World (1530) and appointment of a viceroy (1535)

Cortés returned to Mexico in 1530 with new titles and honors. Although Cortés still retained military authority and permission to continue his conquests, Don

Antonio de Mendoza

Antonio de Mendoza (1495 – 21 July 1552) was a Spanish colonial administrator who was the first viceroy of New Spain, serving from 14 November 1535 to 25 November 1550, and the second viceroy of Peru, from 23 September 1551, until his d ...

was appointed in 1535 as a viceroy to administer New Spain's civil affairs. This division of power led to continual dissension, and caused the failure of several enterprises in which Cortés was engaged. On returning to Mexico, Cortés found the country in a state of

anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

. There was a strong suspicion in court circles of an intended rebellion by Cortés.

After reasserting his position and reestablishing some sort of order, Cortés retired to his estates at

Cuernavaca

Cuernavaca (; , "near the woods" , Otomi language, Otomi: ) is the capital and largest city of the Mexican state, state of Morelos in Mexico. Along with Chalcatzingo, it is likely one of the origins of the Mesoamerica, Mesoamerican civilizatio ...

, about south of Mexico City. There he concentrated on the building of his palace and on Pacific exploration. Remaining in Mexico between 1530 and 1541, Cortés quarreled with

Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán and disputed the right to explore the territory that is today

California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

with

Antonio de Mendoza

Antonio de Mendoza (1495 – 21 July 1552) was a Spanish colonial administrator who was the first viceroy of New Spain, serving from 14 November 1535 to 25 November 1550, and the second viceroy of Peru, from 23 September 1551, until his d ...

, the first viceroy.

Cortés acquired several silver mines in

Zumpango del Rio in 1534. By the early 1540s, he owned 20 silver mines in

Sultepec, 12 in

Taxco

Taxco de Alarcón (; usually referred to as simply Taxco) is a small city and administrative center of Taxco de Alarcón Municipality located in the Mexico, Mexican state of Guerrero. Taxco is located in the north-central part of the state, from ...

, and 3 in

Zacualpan. Earlier, Cortés had claimed the silver in the

Tamazula area.

In 1536, Cortés explored the northwestern part of Mexico and discovered the

Baja California peninsula. Cortés also spent time exploring the Pacific coast of Mexico. The

Gulf of California

The Gulf of California (), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Vermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja California peninsula from ...

was originally named the ''Sea of Cortés'' by its discoverer

Francisco de Ulloa in 1539. This was the last major expedition by Cortés.

Later life and death

Second return to Spain

After his exploration of Baja California, Cortés returned to Spain in 1541, hoping to confound his angry civilians, who had brought many lawsuits against him (for debts, abuse of power, etc.).

On his return he went through a crowd to speak to the emperor, who demanded of him who he was. "I am a man," replied Cortés, "who has given you more provinces than your ancestors left you cities."

Expedition against Algiers

The emperor finally permitted Cortés to join him and his fleet commanded by

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

at the great expedition against

Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

in the

Barbary Coast

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

in 1541, which was then part of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. During this campaign, Cortés was almost drowned in a storm that hit his fleet while he was pursuing the Pasha of Algiers.

Last years, death, and remains

Having spent a great deal of his own money to finance expeditions, he was now heavily in debt. In February 1544 he made a claim on the royal treasury, but was ignored for the next three years. Disgusted, he decided to return to Mexico in 1547. When he reached Seville, he was stricken with

dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

. He died in

Castilleja de la Cuesta,

Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

province, on December 2, 1547, from a case of

pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

at the age of 62.

He left his many

mestizo

( , ; fem. , literally 'mixed person') is a term primarily used to denote people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry in the former Spanish Empire. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturall ...

and white children well cared for in his will, along with every one of their mothers. He requested in his will that his remains eventually be buried in Mexico. Before he died he had the Pope remove the "natural" status of four of his children (legitimizing them in the eyes of the church), including

Martín, the son he had with Doña Marina (also known as La Malinche), said to be his favourite. His daughter, Doña Catalina, however, died shortly after her father's death.

After his death, his body was moved more than eight times for several reasons. On December 4, 1547, he was buried in the

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type o ...

of the Duke of Medina in the church of San Isidoro del Campo, Sevilla. Three years later (1550) due to the space being required by the duke, his body was moved to the altar of Santa Catarina in the same church. In his testament, Cortés asked for his body to be buried in the monastery he had ordered to be built in Coyoacan in México, ten years after his death, but the monastery was never built. So in 1566, his body was sent to New Spain and buried in the church of San Francisco de Texcoco, where his mother and one of his sisters were buried.

In 1629, Cortes's last male descendant Don Pedro Cortés, fourth Marquez del Valle, died. The viceroy decided to move the bones of Cortés along with those of his descendant to the Franciscan church in México. This was delayed for nine years, while his body stayed in the main room of the palace of the viceroy. Eventually it was moved to the Sagrario of Franciscan church, where it stayed for 87 years. In 1716, it was moved to another place in the same church. In 1794, his bones were moved to the "

Hospital de Jesus" (founded by Cortés), where a statue by

Tolsá and a mausoleum were made. There was a public ceremony and all the churches in the city rang their bells.

In 1823, after the independence of México, it seemed imminent that his body would be desecrated, so the mausoleum was removed, the statue and the coat of arms were sent to

Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

,

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, to be protected by the Duke of Terranova. The bones were hidden, and everyone thought that they had been sent out of México. In 1836, his bones were moved to another place in the same building.

It was not until November 24, 1946, that they were rediscovered,

thanks to the discovery of a secret document by

Lucas Alamán

Lucas Ygnacio José Joaquín Pedro de Alcántar Juan Bautista Francisco de Paula de Alamán y Escalada (Guanajuato, New Spain, 18 October 1792 – Mexico City, Mexico, 2 June 1853) was a Mexican scientist, conservative statesman, historian, and ...

. His bones were put in the charge of the

Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH, ''National Institute of Anthropology and History'') is a Federal government of the United Mexican States, Mexican federal government bureau established in 1939 to guarantee the researc ...

(INAH). The remains were authenticated by INAH.

They were then restored to the same place, this time with a bronze inscription and his coat of arms.

When the bones were first rediscovered, the supporters of the Hispanic tradition in Mexico were excited, but one supporter of an indigenist vision of Mexico "proposed that the remains be publicly burned in front of the statue of Cuauhtemoc, and the ashes flung into the air".

Following the discovery and authentication of Cortés's remains, there was a discovery of what were described as the bones of

Cuauhtémoc

Cuauhtémoc (, ), also known as Cuauhtemotzín, Guatimozín, or Guatémoc, was the Aztec ruler ('' tlatoani'') of Tenochtitlan from 1520 to 1521, and the last Aztec Emperor. The name Cuauhtemōc means "one who has descended like an eagle", an ...

, resulting in a "battle of the bones".

On December 16, 1560, the lawsuits related to

vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s of the Cortes estate were resolved by a

royal order issued by

Philip II.

Taxa named after Cortés

Cortés is commemorated in the scientific name of a subspecies of Mexican lizard, ''

Phrynosoma orbiculare cortezii''.

Disputed interpretation of his life

There are relatively few sources to the early life of Cortés; his fame arose from his participation in the conquest of Mexico and it was only after this that people became interested in reading and writing about him.

Probably the best source is his letters to the king which he wrote during the campaign in Mexico, but they are written with the specific purpose of putting his efforts in a favourable light and so must be read critically. Another main source is the biography written by Cortés's private chaplain

Lopez de Gómara, which was written in Spain several years after the conquest. Gómara never set foot in the Americas and knew only what Cortés had told him, and he had an affinity for knightly romantic stories which he incorporated richly in the biography. The third major source is written as a reaction to what its author calls "the lies of Gomara", the eyewitness account written by the Conquistador

Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experienced ...

which does not paint Cortés as a

romantic hero

The Romantic hero is a literary archetype referring to a character that rejects established norms and conventions, has been rejected by society, and has themselves at the center of their own existence. The Romantic hero is often the protagonist i ...

, but rather tries to emphasize that Cortés's men should also be remembered as important participants in the undertakings in Mexico.

In the years following the conquest more critical accounts of the Spanish arrival in Mexico were written. The

Dominican friar

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilian priest named Dominic de Guzmán. It was approved by Pope Honorius ...

Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ); 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a Spanish clergyman, writer, and activist best known for his work as an historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman, then became ...

wrote his ''

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies'' which raises strong accusations of brutality and heinous violence towards the Indians; accusations against both the conquistadors in general and Cortés in particular.

The accounts of the conquest given in the

Florentine Codex by the Franciscan

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún ( – 5 February 1590) was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain (now Mexico). Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he jour ...

and his native informants are also less than flattering towards Cortés. The scarcity of these sources has led to a sharp division in the description of Cortés's personality and a tendency to describe him as either a vicious and ruthless person or a noble and honorable cavalier.

Representations in Mexico

In México there are few representations of Cortés. However, many landmarks still bear his name, from the castle

Palacio de Cortés in the city of

Cuernavaca

Cuernavaca (; , "near the woods" , Otomi language, Otomi: ) is the capital and largest city of the Mexican state, state of Morelos in Mexico. Along with Chalcatzingo, it is likely one of the origins of the Mesoamerica, Mesoamerican civilizatio ...

to some street names throughout the republic.

The pass between the volcanoes

Iztaccíhuatl and

Popocatépetl where Cortés took his soldiers on their march to Mexico City is known as the

Paso de Cortés.

The

mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

ist

Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

painted several representation of him but the most famous, depicts him as a powerful and ominous figure along with Malinche in a mural in the

National Palace Buildings called National Palace include:

*National Palace (Dominican Republic), in Santo Domingo

* National Palace (El Salvador), in San Salvador

* National Palace (Ethiopia), in Addis Ababa; also known as the Jubilee Palace

* National Palace (Guat ...

in Mexico City.

In 1981, President

Lopez Portillo tried to bring Cortés to public recognition. First, he made public a copy of the bust of Cortés made by

Manuel Tolsá in the

Hospital de Jesús Nazareno with an official ceremony, but soon a nationalist group tried to destroy it, so it had to be taken out of the public.

Today the copy of the bust is in the "Hospital de Jesús Nazareno" while the original is in Naples, Italy, in the

Villa Pignatelli.

Later, another monument, known as "Monumento al Mestizaje" by Julián Martínez y M. Maldonado (1982) was commissioned by Mexican president José López Portillo to be put in the "Zócalo" (Main square) of Coyoacan, near the place of his country house, but it had to be removed to a little known park, the Jardín Xicoténcatl, Barrio de San Diego Churubusco, to quell protests. The statue depicts Cortés,

Malinche and their son Martín.

There is another statue by Sebastián Aparicio, in Cuernavaca, was in a hotel "

El casino de la selva". Cortés is barely recognizable, so it sparked little interest. The hotel was closed to make a commercial center, and the statue was put out of public display by Costco the builder of the commercial center.

Cultural depictions

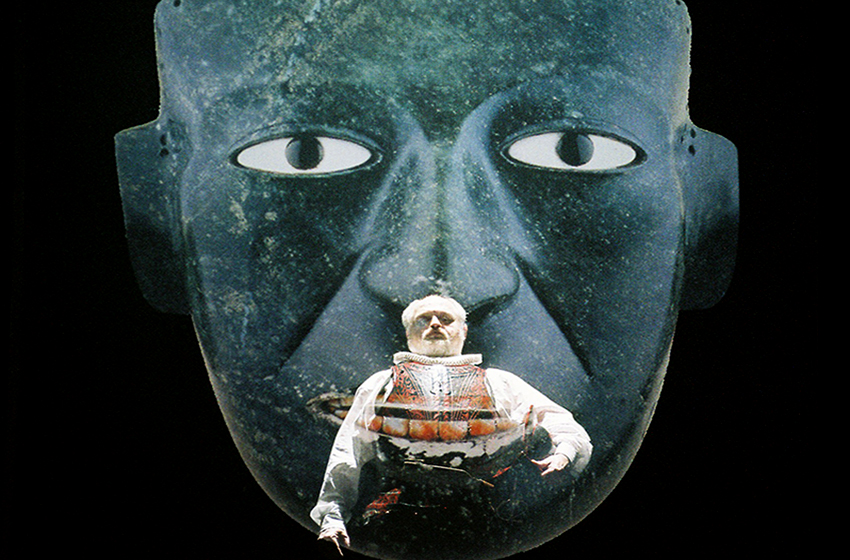

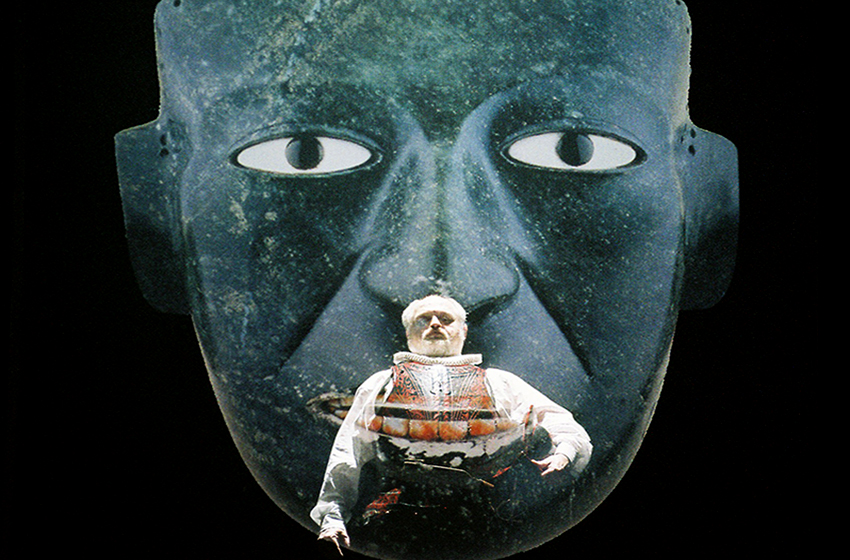

Hernán Cortés is a character in the opera ''

La Conquista'' (2005) by Italian composer

Lorenzo Ferrero, which depicts the major episodes of the

Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was a pivotal event in the history of the Americas, marked by the collision of the Aztec Triple Alliance and the Spanish Empire. Taking place between 1519 and 1521, this event saw the Spanish conquistad ...

in 1521.

Writings: the ''Cartas de Relación''

Cortés's personal account of the conquest of Mexico is narrated in his five letters addressed to Charles V. These five letters, the ', are Cortés's only surviving writings. See "Letters and Dispatches of Cortés", translated by George Folsom (New York, 1843); Prescott's "Conquest of Mexico" (Boston, 1843); and Sir Arthur Helps's "Life of Hernando Cortes" (London, 1871).

His first letter was considered lost, and the one from the municipality of

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

has to take its place. It was published for the first time in volume IV of "Documentos para la Historia de España", and subsequently reprinted.

The ''Segunda Carta de Relacion'', bearing the date of October 30, 1520, appeared in print at

Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

in 1522. The

third letter, dated May 15, 1522, appeared at Seville in 1523. The fourth, October 20, 1524, was printed at

Toledo in 1525. The fifth, on the Honduras expedition, is contained in volume IV of the ''Documentos para la Historia de España''.

Children

Natural children of Don Hernán Cortés

* ''doña'' Catalina Pizarro, born between 1514 and 1515 in

Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

or maybe later in

Nueva España, daughter of an indigenous woman in Cuba, Leonor Pizarro. Doña Catalina married Juan de Salcedo, a conqueror and encomendero, with whom she had a son, Pedro.

* ''don''

Martín Cortés, born in

Coyoacán