Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen or ''

Lij'' Tafari; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was

Emperor of Ethiopia

The emperor of Ethiopia (, "King of Kings"), also known as the Atse (, "emperor"), was the hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Ethiopian Empire, from at least the 13th century until the abolition of the monarchy in 1975. The emperor w ...

from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as the

Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (') under Empress

Zewditu

Zewditu (, born Askala Maryam; 29 April 1876 – 2 April 1930) was Empress of Ethiopia from 1916 until her death in 1930. She was officially renamed Zewditu at the beginning of her reign as Empress of Ethiopia. Once she succeeded the throne af ...

between 1916 and 1930. Widely considered to be a defining figure in modern

Ethiopian history

Ethiopia is one of the oldest countries in Africa; the emergence of Ethiopian civilization dates back thousands of years. Abyssinia or rather "Ze Etiyopia" was ruled by the Semitic Abyssinians (Habesha) composed mainly of the Amhara people, Amhara, ...

, he is accorded divine importance in

Rastafari

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by Religious studies, scholars of religion. There is no central authori ...

, an

Abrahamic religion

The term Abrahamic religions is used to group together monotheistic religions revering the Biblical figure Abraham, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The religions share doctrinal, historical, and geographic overlap that contrasts them wit ...

that emerged in the 1930s. A few years before he began his reign over the

Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

, Selassie defeated Ethiopian army commander

Ras Gugsa Welle Bitul, nephew of Empress

Taytu Betul

Taytu Betul ( ''Ṭaytu Bəṭul'' ; baptised as Wälättä Mikael; 1851 – 11 February 1918) was Empress of Ethiopia from 1889 to 1913 and the third wife of Emperor Menelik II. An influential figure in the anti-colonial resistance during th ...

, at the

Battle of Anchem.

He belonged to the

Solomonic dynasty, founded by Emperor

Yekuno Amlak

Yekuno Amlak (); throne name Tesfa Iyasus (; died 19 June 1285) was Emperor of Ethiopia, from 1270 to 1285, and the founder of the Solomonic dynasty, which lasted until 1974. He was a ruler from Bete Amhara (in parts of modern-day Wollo and ...

in 1270.

Selassie, seeking to modernise Ethiopia, introduced political and social reforms including the

1931 constitution and the

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

in 1942. He led the empire during the

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Fascist Italy, Italy against Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is oft ...

, and after its defeat was exiled to the United Kingdom. When the

Italian occupation of East Africa began, he traveled to

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

to coordinate the Ethiopian struggle against

Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

; he returned home after the

East African campaign of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He dissolved the

Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea

The Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea was a federation between the former Italian Eritrea, Italian colony of Eritrea (1952–1962), Eritrea and the Ethiopian Empire. It was established as a result of the renunciation of Italy’s rights and tit ...

, established by the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

in 1950, and annexed

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

as one of

Ethiopia's provinces, while also

fighting to prevent Eritrean secession.

As an

internationalist, Selassie led Ethiopia's accession to the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

. In 1963, he presided over the formation of the

Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

, the precursor of the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, and served as its first chairman. By the early 1960s, prominent

African socialists such as

Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

envisioned the creation of a "

United States of Africa

The United States of Africa is a concept of a federation of some or all of the 54 sovereign states and two disputed states on the continent of Africa. The concept takes its origin from Marcus Garvey's 1924 poem "Hail, United States of Africa". ...

". Their rhetoric was

anti-Western; Selassie saw this as a threat to his alliances. He attempted to influence a more moderate posture within the group.

Amidst popular uprisings, Selassie was overthrown by the

Derg

The Derg or Dergue (, ), officially the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), was the military junta that ruled Ethiopia, including present-day Eritrea, from 1974 to 1987, when they formally "Civil government, civilianized" the ...

in the

1974 Ethiopian coup d'état

On 12 September 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed by the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army, a Soviet-backed military junta that consequently ruled Ethiopia as the Derg until 28 May 1991.

In February 1 ...

. With support from the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the Derg began governing Ethiopia as a

Marxist–Leninist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

. In 1994, three years after the

fall of the Derg military junta, it was revealed to the public that the Derg had assassinated Selassie at the

Jubilee Palace in

Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

on 27 August 1975.

On 5 November 2000,

his excavated remains were buried at the

Holy Trinity Cathedral of Addis Ababa.

Among adherents of

Rastafari

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by Religious studies, scholars of religion. There is no central authori ...

, Selassie is called the

returned Jesus, although he was an adherent of the

Ethiopian Orthodox Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church () is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Christian churches in Africa originating before European colonization of the continent, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church dates bac ...

himself. He has been criticised for his suppression of rebellions among the landed aristocracy ('), which consistently opposed his changes. Others have criticised Ethiopia's failure to modernise rapidly enough.

During his reign, the

Harari people

The Harari people ( Harari: / , Gēy Usuach, "People of the City") are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group which inhabits the Horn of Africa. Members of this ethnic group traditionally reside in the walled city of Harar, simply called ''Gēy'' "the ...

were persecuted and many left their homes.

His administration was criticised as autocratic and illiberal by groups such as

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

.

[ (taken from Chapter 3 of ''Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia'' Alexander de Waal (Africa Watch, 1991))] According to some sources, late into Selassie's administration, the

Oromo language

Oromo, historically also called Galla, is an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic branch, primarily spoken by the Oromo people, native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia; and northern Kenya. It is used as a lingua franca in Oromia an ...

was banned from education, public speaking and use in administration, though there was never a law that criminalised any language.

His government relocated many

Amhara people

Amharas (; ) are a Ethiopian Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking ethnic group indigenous to Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa, traditionally inhabiting parts of the northwest Ethiopian Highlands, Highlands of Ethiopia, particularly the Amhara Reg ...

into southern Ethiopia. Following the death of Ethiopian civil rights activist

Hachalu Hundessa in 2020,

his bust in the United Kingdom was destroyed by Oromo protesters, and an equestrian monument depicting his father was removed from

Harar

Harar (; Harari language, Harari: ሀረር / ; ; ; ), known historically by the indigenous as Harar-Gey or simply Gey (Harari: ጌይ, ݘٛىيْ, ''Gēy'', ), is a List of cities with defensive walls, walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is al ...

.

Name

Haile Selassie was known as a child as Lij Tafari Makonnen (). ''

Lij'' is translated as "child" and serves to indicate that a youth is of noble blood. His given name ''Tafari'' means "one who is respected or feared". Like most Ethiopians, his personal name "Tafari" is followed by that of his father

Makonnen and that of his grandfather Woldemikael. His name ''Haile Selassie'' was given to him at his infant baptism and adopted again as part of his

regnal name

A regnal name, regnant name, or reign name is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they accede ...

in 1930.

On 1 November 1905, at the age of 13, Tafari was appointed by his father as the Dejazmatch of Gara Mulatta (a region some twenty miles southwest of Harar).

The literal translation of Dejazmatch is "keeper of the door"; it is a title of nobility equivalent to a

count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

. On 27 September 1916, he was proclaimed Crown Prince and heir apparent to the throne (''Alga Worrach''),

and appointed

Regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

Plenipotentiary (''Balemulu Silt'an

Enderase

Until the end of the Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, ...

'').

On 11 February 1917, he was crowned Le'ul-Ras

and became known as

Ras Tafari Makonnen . ''

Ras'' is translated as "head"

[Copley, Gregory R. ''Ethiopia Reaches Her Hand Unto God: Imperial Ethiopia's Unique Symbols, Structures and Role in the Modern World''. Published by Defense & Foreign Affairs, part of the International Strategic Studies Association, 1998. . p. 114] and is a rank of nobility equivalent to a

duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

,

though it is often rendered in translation as "prince". Originally the title ''

Le'ul

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

'', which means "Your Highness", was only ever used as a form of address;

however, in 1916 the title ''Le'ul-Ras'' replaced the senior office of ''Ras

Bitwoded

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

'' and so became the equivalent of a

royal duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they a ...

. In 1928,

Empress Zewditu planned on granting him the throne of Shewa; however, at the last moment opposition from certain provincial rulers caused a change and his title ''

Negus

''Negus'' is the word for "king" in the Ethiopian Semitic languages and a Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, title which was usually bestowed upon a regional ruler by the Ethiopian Emperor, Negusa Nagast, or "king of kings," in pre-1974 Et ...

'' or "King" was conferred without geographical qualification or definition.

On 2 November 1930, after the death of Empress Zewditu, Tafari was crowned ''Negusa Nagast'', literally "King of Kings", rendered in English as "Emperor".

Upon his ascension, he took as his regnal name Haile Selassie I. ''Haile'' means in Ge'ez "Power of" and ''Selassie'' means

trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

therefore ''Haile Selassie'' roughly translates to "Power of the Trinity". Selassie's full title in office was "By the Conquering

Lion of the Tribe of Judah

The Lion of Judah (, ) is a Jewish national and cultural symbol, traditionally regarded as the symbol of the tribe of Judah. The association between the Judahites and the lion can first be found in the blessing given by Jacob to his fourth son ...

,

His Imperial Majesty

Imperial Majesty (''His/Her Imperial Majesty'', abbreviated as ''HIM'') is a style used by Emperors and Empresses. It distinguishes the status of an emperor/empress from that of a King/Queen, who are simply styled Majesty. Holders of this style ...

Haile Selassie I,

King of Kings

King of Kings, ''Mepet mepe''; , group="n" was a ruling title employed primarily by monarchs based in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Commonly associated with History of Iran, Iran (historically known as name of Iran, Persia ...

of Ethiopia, Lord of Lords, Elect of God".

This title reflects Ethiopian dynastic traditions, which hold that all monarchs must trace their lineage to

Menelik I

Menelik I ( Ge'ez: ምኒልክ, ''Mənilək'') was the legendary first Emperor of Ethiopia's Solomonic dynasty. According to '' Kebra Nagast'', a 14th-century national epic, in the 10th century BC he is said to have inaugurated the Solomonic d ...

, who is described by the

Kebra Nagast

The Kebra Nagast (, ), or The Glory of the Kings, is a 14th-century national epic of Ethiopia, written in Geʽez by the nebure id Ishaq of Aksum. In its existing form, the text is at least 700 years old and purports to trace the origins of the ...

(a 14th-century CE national epic) as the son of the tenth-century BCE

King Solomon

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by f ...

and the

Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

.

To Ethiopians, Selassie has been known by many names, including Janhoy ("His Majesty") Talaqu Meri ("Great Leader") and Abba Tekel ("Father of Tekel", his

horse name

A horse name is a secondary nobility, noble title or a popular name for members of Ethiopian royal family, royalty; in some cases the "horse names" are the only name known for a ruler. They take the form of "father of X", where "X" is the name of ...

).

The

Rastafari movement

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by scholars of religion. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much ...

employs many of these appellations, also referring to him as

Jah

Jah or Yah (, ''Yāh'') is a short form of the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), the personal name of God: Yahweh, which the ancient Israelites used. The conventional Christian English pronunciation of ''Jah'' is , even though the letter J here transliter ...

, Jah Jah, Jah Rastafari, and HIM (the abbreviation of "His Imperial Majesty").

Early life

File:Tafari Makonnen dressed in warrior garments.jpg, Then Tafari Makonnen wearing a warrior's dress

File:Lij Teferi and his father, Ras Makonnen.jpg, Ras Makonnen Woldemikael

''Ras'' Makonnen Wolde Mikael Wolde Melekot (; 8 May 1852 – 21 March 1906), or simply Ras Makonnen, also known as Abba Qagnew (አባ ቃኘው), was an Ethiopian royal from Shewa, a military leader, the governor of Harar, and the fathe ...

and his son Lij Tafari Makonnen

Tafari's royal line (through his paternal grandmother) descended from the Shewan

Amhara Solomonic king,

Sahle Selassie

Sahle Selassie (Amharic: ሣህለ ሥላሴ, 1795 – 22 October 1847) was the Negus, King of Shewa from 1813 to 1847. An important Amhara people, Amhara noble of Ethiopia, he was a younger son of Wossen Seged. Sahle Selassie was the father of ...

. He was born on 23 July 1892, in the village of

Ejersa Goro, in the

Hararghe

Hararghe ( ''Harärge''; Harari language, Harari: ሀረርጌ፞ይ, هَرَرْݘٛىيْ,''Harargêy'', Oromo language, Oromo: Harargee, ) was a provinces of Ethiopia, province of eastern Ethiopia with its capital in Harar.

Etymology

Harargh ...

province of Ethiopia. Tafari's mother,

Woizero ("Lady")

Yeshimebet Ali

''Woizero'' Yeshimebet Ali was the wife of Ras Makonnen and mother of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. She was the daughter of Dejazmatch Ali Gonshur, who was from Oromo and a former trader from Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amhari ...

Abba Jifar, was paternally of

Oromo Oromo may refer to:

* Oromo people, an ethnic group of Ethiopia and Kenya

* Oromo language, an Afroasiatic language

See also

*

*Orma (clan), Oromo tribe

*Oromia

Oromia (, ) is a Regions of Ethiopia, regional state in Ethiopia and the homelan ...

descent and maternally of

Silte heritage, while his father,

Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael

Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, ''Ras'' Makonnen Wolde Mikael Wolde Melekot (; 8 May 1852 – 21 March 1906), or simply Ras Makonnen, also known as Abba Qagnew (አባ ቃኘው), was an Ethiopian royal from Shewa, a military lead ...

, was maternally of

Amhara descent but his paternal lineage remains disputed.

[Woodward, Peter (1994), ''Conflict and Peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives''. Dartmouth Pub. Co. , p. 29.] Tafari's paternal grandfather belonged to a noble family from

Shewa

Shewa (; ; Somali: Shawa; , ), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa, is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located at it ...

and was the governor of the districts of

Menz

Menz or Manz (, romanized: ''Mänz'') is a former Subdivisions of Ethiopia, subdivision of Ethiopia, located inside the boundaries of the modern Semien Shewa Zone (Amhara), Semien Shewa Zone of the Amhara Region. William Cornwallis Harris describe ...

and

Doba, which are located in

Semien Shewa.

[S. Pierre Pétridès, ''Le Héros d'Adoua. Ras Makonnen, Prince d'Éthiopie'', ] Tafari's mother was the daughter of a ruling chief from

Were Ilu in

Wollo

Wollo (Amharic: ወሎ) was a historical province of northern Ethiopia. During the Middle Ages this province name was Bete Amhara and it was the centre of the Solomonic emperors. Bete Amhara had an illustrious place in Ethiopian political and ...

province,

Dejazmach

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

Ali Abba Jifar.

[de Moor, Jaap, and Wesseling, H. L. (1989), ''Imperialism and War: Essays on Colonial Wars in Asia and Africa''. Brill. , p. 189.] Ras Makonnen was the grandson of King

Sahle Selassie

Sahle Selassie (Amharic: ሣህለ ሥላሴ, 1795 – 22 October 1847) was the Negus, King of Shewa from 1813 to 1847. An important Amhara people, Amhara noble of Ethiopia, he was a younger son of Wossen Seged. Sahle Selassie was the father of ...

who was once the ruler of

Shewa

Shewa (; ; Somali: Shawa; , ), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa, is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located at it ...

. He served as a general in the

First Italo–Ethiopian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the First Italo-Abyssinian War, or simply known as the Abyssinian War in Italy (), was a military confrontation fought between Kingdom of Italy, Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from 1895 to ...

, playing a key role at the

Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian army defeated an invading Italian and Eritrean force led by Oreste Baratieri on March 1, 1896, near the town of Adwa. ...

;

Selassie was thus able to ascend to the imperial throne through his paternal grandmother, Woizero Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, who was an aunt of Emperor

Menelik II

Menelik II ( ; horse name Aba Dagnew (Amharic: አባ ዳኘው ''abba daññäw''); 17 August 1844 – 12 December 1913), baptised as Sahle Maryam (ሣህለ ማርያም ''sahlä maryam'') was king of Shewa from 1866 to 1889 and Emperor of Et ...

and daughter of the Solomonic Amhara King of Shewa,

Negus

''Negus'' is the word for "king" in the Ethiopian Semitic languages and a Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, title which was usually bestowed upon a regional ruler by the Ethiopian Emperor, Negusa Nagast, or "king of kings," in pre-1974 Et ...

Sahle Selassie. As such, Selassie claimed direct descent from

Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon of ancient Israel.

Ras Makonnen arranged for Tafari as well as his first cousin,

Imru Haile Selassie

Leul Ras Imru Haile Selassie, CBE (Amharic: ዕምሩ ኀይለ ሥላሴ; 23 November 1892 – 15 August 1980) was an Ethiopian noble, soldier, and diplomat. He served as acting Prime Minister for three days in 1960 during a coup d'éta ...

, to receive instruction in Harar from

Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin

Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin (also spelled Walda Kahen; Amharic: አባ ሳሙኤል ወልደ ካህን) was the tutor and mentor of '' Ras'' Tafari Makonnen (later Emperor Haile Selassie I) and his cousin, ''Ras'' Imru Haile Selassie, when the two we ...

, an Ethiopian

Capuchin friar, and from Dr. Vitalien, a surgeon from

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

. Tafari was named

Dejazmach

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

(literally "commander of the gate", roughly equivalent to "

count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

") at the age of 13, on 1 November 1905.

[.] Shortly thereafter, his father Makonnen died at

Kulibi, in 1906.

[.]

Governorship

Tafari assumed the titular governorship of Selale in 1906, a realm of marginal importance,

[.] but one that enabled him to continue his studies.

In 1907, he was appointed governor over part of the province of

Sidamo. It is alleged that during his late teens, Selassie was married to ''Woizero'' Altayech, and that from this union, his daughter

Princess Romanework

Princess Romanework Haile Selassie, sometimes spelt as Romane Work Haile Selassie (died in Turin on 14 October 1940), was the eldest child of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia by his first wife, ''Woizero'' Altayech.Mockler, Anthony, ''Haile Sela ...

was born.

Following the death of his brother Yelma in 1907, the governorate of Harar was left vacant,

and its administration was left to Menelik's loyal general, ''Dejazmach''

Balcha Safo

'' Dejazmach'' Balcha Safo (; 1863 – 6 November 1936), popularly referred to by his horse-name Abba Nefso, was an Ethiopian military commander and lord protector of the crown, who served in both the First and Second Italo-Ethiopian Wars.Pau ...

. Balcha Safo's administration of Harar was ineffective, and so during the last illness of Menelik II, and the brief reign of Empress

Taytu Betul

Taytu Betul ( ''Ṭaytu Bəṭul'' ; baptised as Wälättä Mikael; 1851 – 11 February 1918) was Empress of Ethiopia from 1889 to 1913 and the third wife of Emperor Menelik II. An influential figure in the anti-colonial resistance during th ...

, Tafari was made governor of Harar in 1910 or 1911.

[Mockler, Anthony, ''Haile Selassie's War'' (2003), p. xxvii]

Marriage

On 3 August 1911, Tafari married

Menen Asfaw

Menen Asfaw (baptismal name: Walatta Giyorgis; 25 March 1889 – 15 February 1962) was Empress of Ethiopia as the wife of Emperor Haile Selassie.

Family

Menen Asfaw was born in Ambassel, located in Wollo Province of Ethiopian Empire on 25 Ma ...

of

Ambassel

Ambassel () is a woreda in Amhara Region, Ethiopia, and an '' amba'', or mountain fortress, located in the woreda. The word Ambasel is derived from two words "Amba" from the Amharic word for plateau, and “Asel” from the Arabic language, which ...

, niece of the heir to the throne

Lij Iyasu

''Lij'' Iyasu (; 4 February 1895 – 25 November 1935) was the designated Emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. His baptismal name was Kifle Yaqob (ክፍለ ያዕቆብ ''kəflä y’aqob''). Ethiopian emperors traditionally chose their regna ...

. Menen Asfaw was 22 years old while Tafari was 19 years of age. Menen had already married two previous noblemen, while Tafari had one previous wife and one child. The marriage between Menen Asfaw and Selassie lasted for 50 years. Although possibly a political match designed to create peace between Ethiopian nobles, the couple's family had said they married with mutual consent. Selassie described his spouse as a "woman without any malice whatsoever".

Regency

The extent to which Tafari Makonnen contributed to the movement that would come to depose

Lij Iyasu

''Lij'' Iyasu (; 4 February 1895 – 25 November 1935) was the designated Emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. His baptismal name was Kifle Yaqob (ክፍለ ያዕቆብ ''kəflä y’aqob''). Ethiopian emperors traditionally chose their regna ...

has been discussed extensively, particularly in Selassie's own detailed account of the matter. Iyasu was the designated but uncrowned emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. Iyasu's reputation for scandalous behavior and a disrespectful attitude towards the nobles at the court of his grandfather, Menelik II, damaged his reputation. Iyasu's flirtation with Islam was considered treasonous among the

Ethiopian Orthodox Christian

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church () is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Christian churches in Africa originating before European colonization of the continent, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church dates bac ...

leadership of the empire. On 27 September 1916, Iyasu was deposed.

Contributing to the movement that deposed Iyasu were conservatives such as ''

Fitawrari

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

''

Habte Giyorgis

'' Fitawrari'' Habte Giyorgis Dinagde (; ; c. 1851 – 12 December 1926) also known by his horse name Abbaa Malaa was an Ethiopian military commander and government official who, among several other posts, served as President of the Council o ...

, Menelik II's longtime Minister of War. The movement to depose Iyasu preferred Tafari, as he attracted support from both progressive and conservative factions. Ultimately, Iyasu was deposed on the grounds of conversion to Islam.

[.] In his place, the daughter of Menelik II (the aunt of Iyasu) was named Empress

Zewditu

Zewditu (, born Askala Maryam; 29 April 1876 – 2 April 1930) was Empress of Ethiopia from 1916 until her death in 1930. She was officially renamed Zewditu at the beginning of her reign as Empress of Ethiopia. Once she succeeded the throne af ...

, while Tafari was elevated to the rank of ''Ras'' and was made

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

and

Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

. In the power arrangement that followed, Tafari accepted the role of

Regent Plenipotentiary (''Balemulu 'Inderase'') and became the ''de facto'' ruler of the

Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

(''Mangista Ityop'p'ya''). Zewditu would govern while Tafari would administer.

While Iyasu had been deposed on 27 September 1916, on 8 October he managed to escape into the

Ogaden Desert and his father, ''Negus''

Mikael of Wollo

'' Negus'' Mikael of Wollo (born Mohammed Ali, 1850 – 8 September 1918), was an army commander and a member of the nobility of the Ethiopian Empire. He was the father of the "uncrowned" Emperor Lij Iyasu, and the grandfather of Empress Menen, ...

, had time to come to his aid.

[.] On 27 October, ''Negus'' Mikael and his army met an army under ''Fitawrari'' Habte Giyorgis loyal to Zewditu and Tafari. During the

Battle of Segale

The Battle of Segale was a civil conflict in the Ethiopian Empire between the supporters of Empress regent Zewditu and Lij Iyasu on 27 October 1916, and resulted in victory for Zewditu. Paul B. Henze states that "Segale was Ethiopia's greatest b ...

, Mikael was defeated and captured. Any chance that Iyasu would regain the throne was ended, and he went into hiding. On 11 January 1921, after avoiding capture for about five years, Iyasu was taken into custody by

Gugsa Araya Selassie

Gugsa Araya Selassie (1885 – 28 April 1932) was an army commander and a member of the royal family of the Ethiopian Empire.

Biography

''Leul'' Gugsa Araya Selassie was the legitimate son of ''Ras'' Araya Selassie Yohannes. Araya Selass ...

.

[Gebre-Igzabiher Elyas, ''Chronicle'', p. 372]

On 11 February 1917, the coronation for Zewditu took place. She pledged to rule justly through her regent, Tafari. While Tafari was the more visible of the two, Zewditu was not simply an honorary ruler, but she did have some political restraints due to the complicated nature of her position compared to other Ethiopian monarchs, one was that it required that she arbitrate the claims of competing factions. In other words, she had the last word. But unlike other monarchs Tafari carried the burden of daily administration, but, initially because his position was relatively weak, this was often an exercise in futility. His personal army was poorly equipped, his finances were limited, and he had little leverage to withstand the combined influence of the Empress, the Minister of War, or the provincial governors. Nonetheless, her authority weakened while Tafari's power increased, she focused on praying and fasting and much less in her official duties which allowed Tafari to later have greater influence than even the Empress.

During his Regency, the new Crown Prince developed the policy of cautious modernisation initiated by Menelik II. Also, during this time, he survived the

1918 flu pandemic

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the Influenza A virus subtype H1N1, H1N1 subtype of the influenz ...

, having come down with the illness as someone fairly "prone to" the effects of disease throughout his life. He secured Ethiopia's admission to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

in 1923 by promising to eradicate slavery; each emperor since

Tewodros II

Tewodros II (, once referred to by the English cognate Theodore; baptized as Kassa, – 13 April 1868) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1855 until his death in 1868. His rule is often placed as the beginning of modern Ethiopia and brought an end to ...

had issued proclamations to halt

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, but without effect: the internationally scorned practice persisted well into Selassie's reign with an estimated 2 million slaves in Ethiopia in the early 1930s.

Travel abroad

In 1924, Ras Tafari toured Europe and the Middle East visiting

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

,

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Paris, Luxembourg, Brussels,

Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, Stockholm, London,

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Gibraltar and

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. With him on his tour was a group that included Ras

Seyum Mangasha

Seyoum Mengesha KBE (Amharic: ሥዩም መንገሻ; 21 June 1887 – 15 December 1960) was an army commander and a member of the royal family of the Ethiopian Empire.

Early life

''Le'ul'' ''Ras'' Seyoum Mengesha was born on 24 June 188 ...

of western

Tigray Province

Tigray Province (), also known as Tigre ( tigrē), was a historical province of northern Ethiopia that overlayed the present day Afar and Tigray regions. Akele Guzai borders with the Tigray province. It encompassed most of the territories of T ...

; Ras

Hailu Tekle Haymanot

Hailu Tekle Haymanot (1868 – 1950), also named Hailu II of Gojjam, was an army commander and a member of the nobility of the Ethiopian Empire. He represented a provincial ruling elite who were often at odds with the Ethiopian central government ...

of

Gojjam

Gojjam ( ''gōjjām'', originally ጐዛም ''gʷazzam'', later ጐዣም ''gʷažžām'', ጎዣም ''gōžžām'') is a historical provincial kingdom in northwestern Ethiopia, with its capital city at Debre Markos.

During the 18th century, G ...

province; Ras

Mulugeta Yeggazu

'' Ras'' Mulugeta Yeggazu (Amharic: ሙሉጌታ ይገዙ; 17 February 1865 – 27 February 1936) was an Ethiopian government official, who served in the first cabinet formed by Emperor Menelik II. He served as Imperial Fitawrari, Commander of ...

of

Illubabor Province

Illubabor (Amharic: ኢሉባቦር) was a Provinces of Ethiopia, province in the south-western part of Ethiopia, along the border with Sudan. The name Illubabor is said to come from two Oromo language, Oromo words, "" and "". "Illu" is a name o ...

; Ras

Makonnen Endelkachew

'' Ras Betwoded'' Mekonnen Endelkachew (Amharic: መኮንን እንዳልካቸው; 16 February 1890 – 27 February 1963) was an Ethiopian aristocrat and Prime Minister under Emperor Haile Selassie. Mekonnen was born in Addisge, the nephe ...

; and ''

Blattengeta''

Heruy Welde Selassie

'' Blatten Geta'' Heruy Welde Sellase ( Ge'ez: ብላቴን ጌታ ኅሩይ ወልደ ሥላሴ ''Blatten-Geta Həruy Wäldä-səllase''; 8 May 1878 – 19 September 1938) was an Ethiopian diplomat who was Foreign Minister of Ethiopia from ...

. The primary goal of the trip to Europe was for Ethiopia to gain access to the sea. In Paris, Tafari was to find out from the

French Foreign Ministry

The Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (, MEAE) is the ministry of the Government of France that handles France's foreign relations. Since 1855, its headquarters have been located at 37 Quai d'Orsay, close to the National Assembly. The ter ...

(''

Quai d'Orsay

The Quai d'Orsay ( , ) is a quay in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. It is part of the left bank of the Seine opposite the Place de la Concorde. It becomes the Quai Anatole-France east of the Palais Bourbon, and the Quai Branly west of the ...

'') that this goal would not be realised. However, failing this, he and his retinue inspected schools, hospitals, factories, and churches. Although patterning many reforms after European models, Tafari remained wary of European pressure. To guard against

economic imperialism

Theories of imperialism are a range of theoretical approaches to understanding the expansion of capitalism into new areas, the unequal development of different countries, and economic systems that may lead to the dominance of some countries over ...

, Tafari required that all enterprises have at least partial local ownership. Of his modernisation campaign, he remarked, "We need European progress only because we are surrounded by it. That is at once a benefit and a misfortune."

Throughout Tafari's travels in Europe, the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, and Egypt, he and his entourage were greeted with enthusiasm and fascination. Seyum Mangasha accompanied him and Hailu Tekle Haymanot who, like Tafari, were sons of generals who contributed to the victorious war against Italy a quarter-century earlier at the

Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian army defeated an invading Italian and Eritrean force led by Oreste Baratieri on March 1, 1896, near the town of Adwa. ...

.

[.] Another member of his entourage, Mulugeta Yeggazu, actually fought at Adwa as a young man. The "Oriental Dignity" of the Ethiopians and their "rich, picturesque court dress" were sensationalised in the media; among his entourage he even included a pride of lions, which he distributed as gifts to President

Alexandre Millerand

Alexandre Millerand (; – ) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1920 to 1924, having previously served as Prime Minister of France earlier in 1920. His participation in Waldeck-Rousseau's cabinet at the start of the ...

and Prime Minister

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

of

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, to King

George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

of the United Kingdom, and to the Zoological Garden (''

Jardin Zoologique'') of Paris, France.

As one historian noted, "Rarely can a tour have inspired so many anecdotes".

In return for two lions, the United Kingdom presented Tafari with the imperial crown of Emperor

Tewodros II

Tewodros II (, once referred to by the English cognate Theodore; baptized as Kassa, – 13 April 1868) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1855 until his death in 1868. His rule is often placed as the beginning of modern Ethiopia and brought an end to ...

for its safe return to Empress Zewditu. The crown had been taken by

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Robert Napier during the

1868 Expedition to Abyssinia

The British Expedition to Abyssinia was a rescue mission and punitive expedition carried out in 1868 by the armed forces of the British Empire against the Ethiopian Empire (also known at the time as Abyssinia). Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, ...

.

In this period, the Crown Prince visited the Armenian monastery of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. There, he adopted 40

Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

orphans (አርባ ልጆች ''

Arba Lijoch'', "forty children"), who had lost their parents during the

Armenian Genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

. Tafari arranged for the musical education of the youths, and they came to form the imperial brass band.

Reign

King and Emperor

Tafari's authority was challenged in 1928 when ''

Dejazmach

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The Mesafint ( , modern transcription , singular መስፍን , modern , "prince"), the hereditary royal nobility, formed the upper ...

''

Balcha Safo

'' Dejazmach'' Balcha Safo (; 1863 – 6 November 1936), popularly referred to by his horse-name Abba Nefso, was an Ethiopian military commander and lord protector of the crown, who served in both the First and Second Italo-Ethiopian Wars.Pau ...

went to Addis Ababa with a sizeable armed force. When Tafari consolidated his hold over the provinces, many of Menelik's appointees refused to abide by the new regulations. Balcha Safo, the governor (''Shum'') of coffee-rich

Sidamo Province

Sidamo Province (Amharic: ሲዳሞ) was a province in the southern part of Ethiopia, with its capital city at Irgalem, and after 1978 at Awasa. It was named after an ethnic group native to southern Ethiopia, called the Sidama, who are located ...

, was particularly troublesome. The revenues he remitted to the central government did not reflect the accrued profits and Tafari recalled him to Addis Ababa. The old man came in high dudgeon and, insultingly, with a large army. The ''Dejazmatch'' paid homage to Empress Zewditu, but snubbed Tafari.

[.] On 18 February, while Balcha Safo and his personal bodyguard were in Addis Ababa, Tafari had ''Ras''

Kassa Haile Darge

'' Ras'' Kassa Hailu (Amharic: ካሣ ኀይሉ ዳርጌ; 7 August 1881 – 16 November 1956) was a Shewan Amhara nobleman, the son of Dejazmach Haile Wolde Kiros of Lasta, the ruling heir of Lasta's throne and younger brother of Emperor ...

buy off Balcha Safo's army, and arranged to have him replaced as ''Shum'' of Sidamo Province by Birru Wolde Gabriel – who himself was replaced by

Desta Damtew

''Ras'' Desta Damtew KBE (Amharic: ደስታ ዳምጠው; ''c.'' 1892 – 24 February 1937) was an Ethiopian noble, army commander and a son-in-law of Emperor Haile Selassie I. He is known for his leadership in the Ethiopian Army during the ...

.

Even so, the gesture of Balcha Safo empowered Empress Zewditu politically and she attempted to have Tafari tried for

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

. He was tried for his benevolent dealings with Italy including a

20-year peace accord that was signed on 2 August.

In September, a group of palace reactionaries including some courtiers of the Empress made a

final bid to get rid of Tafari. The attempted ''coup d'état'' was tragic in its origins and comic in its end. When confronted by Tafari and a company of his troops, the ringleaders of the coup took refuge on the palace grounds in Menelik's mausoleum. Tafari and his men surrounded them, only to be surrounded themselves by the personal guard of Zewditu. More of Tafari's khaki clad soldiers arrived and decided the outcome in his favor with superiority of arms. Popular support, as well as the support of the police,

remained with Tafari. Ultimately, the Empress relented, and, on 7 October 1928, she crowned Tafari as ''

Negus

''Negus'' is the word for "king" in the Ethiopian Semitic languages and a Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, title which was usually bestowed upon a regional ruler by the Ethiopian Emperor, Negusa Nagast, or "king of kings," in pre-1974 Et ...

'' (

Amharic

Amharic is an Ethio-Semitic language, which is a subgrouping within the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages. It is spoken as a first language by the Amhara people, and also serves as a lingua franca for all other metropolitan populati ...

: "King").

The crowning of Tafari as King was controversial. He occupied the same territory as the Empress rather than going off to a regional kingdom of the empire. Two monarchs, even with one being the vassal and the other the emperor (in this case empress), had never ruled from a single location simultaneously in

Ethiopian history

Ethiopia is one of the oldest countries in Africa; the emergence of Ethiopian civilization dates back thousands of years. Abyssinia or rather "Ze Etiyopia" was ruled by the Semitic Abyssinians (Habesha) composed mainly of the Amhara people, Amhara, ...

. Conservatives agitated to redress this perceived insult to the crown's dignity, leading to the

''Ras'' Gugsa Welle's rebellion.

Gugsa Welle

Gugsa Welle (1875 – 31 March 1930; as spelled as Gugsa Wale or Gugsa Wolie, and cited as Ras Gugsà Oliè in Italian books and encyclopedias), was an Ethiopian army commander and a member of the imperial family of the Ethiopian Empire. He repre ...

was the husband of the Empress and the ''Shum'' of

Begemder

Begemder (; also known as Gondar or Gonder) was a province in northwest Ethiopia. The alternative names come from its capital during the 20th century, Gondar.

Etymology

A plausible source for the name ''Bega'' is that the word means "dry" in t ...

Province. In early 1930, he raised an army and marched it from his governorate at

Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amharic: ጎንደር, ''Gonder'' or ''Gondär''; formerly , ''Gʷandar'' or ''Gʷender''), is a city and woreda in Ethiopia. Located in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Gondar is north of Lake Tana on ...

towards

Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

. On 31 March 1930, Gugsa Welle was met by forces loyal to ''Negus'' Tafari and was defeated at the

Battle of Anchem. Gugsa Welle was

killed in action

Killed in action (KIA) is a casualty classification generally used by militaries to describe the deaths of their personnel at the hands of enemy or hostile forces at the moment of action. The United States Department of Defense, for example, ...

. News of Gugsa Welle's defeat and death had hardly spread through Addis Ababa when the Empress died suddenly on 2 April 1930. Although it was long rumored that the Empress was poisoned upon her husband's defeat, or alternately that she died from shock upon hearing of the death of her estranged yet beloved husband, it has since been documented that Zewditu succumbed to

paratyphoid fever

Paratyphoid fever, also known simply as paratyphoid, is a bacterial infection caused by one of three types of '' Salmonella enterica''. Symptoms usually begin 6–30 days after exposure and are the same as those of typhoid fever. Often, a gradu ...

and complications from

diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

after the Orthodox clergy imposed strict rules concerning her diet during Lent, against her physicians' orders.

Upon Zewditu's death, Tafari himself rose to emperor and was proclaimed ''Neguse Negest ze-'Ityopp'ya'', "King of Kings of Ethiopia". He was

crowned on 2 November 1930, at

Addis Ababa's Cathedral of St. George. The coronation was by all accounts "a most splendid affair",

[.] and it was attended by royals and dignitaries from all over the world. Among those in attendance were the

Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester ( ) is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

(King George V's son),

Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

Louis Franchet d'Espèrey

Louis may refer to:

People

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

Other uses

* Louis (coin), a French coin

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

...

of France, and the

Prince of Udine representing King

Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

of Italy. Special

Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

Herman Murray Jacoby attended the coronation as the personal representative of U.S. president

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

. Emissaries from Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Belgium, and Japan were there.

British author

Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

was also present, penning a contemporary report on the event, and American travel lecturer

Burton Holmes

Elias Burton Holmes (January 8, 1870 – July 22, 1958) was an American traveler, photographer and filmmaker credited with the invention of the " travelogue", though the term itself was apparently coined in 1898 by John Bowker. Travel stories, ...

made the only known film footage of the event. One American newspaper report suggested that the celebration had incurred a cost in excess of $3,000,000. Many of those in attendance received lavish gifts; in one instance the Emperor, a Christian, even sent a gold-encased Bible to an American bishop who had not attended the coronation, but who had dedicated a prayer for the Emperor on the day of the coronation.

Selassie introduced

Ethiopia's first written constitution on 16 July 1931, providing for a

bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single ...

.

[Fasil (1997), ''Constitution for a Nation of Nations'', p. 22.] The constitution kept power in the hands of the nobility, but it did establish democratic standards among the nobility, envisaging a transition to democratic rule: it would prevail "until the people are in a position to elect themselves."

The constitution limited succession to the throne to descendants of Selassie, which had the effect of placing other dynastic princes at the time (including the princes of

Tigrai, and even the Emperor's loyal cousin Ras

Kassa Haile Darge

'' Ras'' Kassa Hailu (Amharic: ካሣ ኀይሉ ዳርጌ; 7 August 1881 – 16 November 1956) was a Shewan Amhara nobleman, the son of Dejazmach Haile Wolde Kiros of Lasta, the ruling heir of Lasta's throne and younger brother of Emperor ...

) outside of the line for the throne.

In 1932, the

Sultanate of Jimma was formally absorbed into Ethiopia following the death of Sultan

Abba Jifar II

''Moti'' Abba Jifar II (; 1861 – 1932) was King of the Gibe Kingdom of Jimma (r. 1878–1932).

Reign

Abba Jifar II was king of Jimma, and the son of Abba Gomol and Queen Gumiti. He had several wives: Queen Limmiti, who was the daughter o ...

of

Jimma

Jimma () is the largest city in southwestern Oromia Region, Ethiopia. It is a special zone of the Oromia Region and is surrounded by Jimma Zone. It has a latitude and longitude of . Prior to the 2007 census, Jimma was reorganized administrativ ...

.

[Harold G. Marcus, ''The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844–1913'' (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1995), p. 121]

Conflict with Italy

Ethiopia became the target of renewed Italian imperialist designs in the 1930s.

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's

Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

regime was keen to avenge the military defeats Italy had suffered to Ethiopia in the

First Italo-Abyssinian War

The First Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the First Italo-Abyssinian War, or simply known as the Abyssinian War in Italy (), was a military confrontation fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from the disput ...

, and to efface the failed attempt by "liberal" Italy to conquer the country, as epitomised by the defeat at

Adwa

Adwa (; ; also spelled Adowa or Aduwa) is a town and separate woreda in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. It is best known as the community closest to the site of the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Ethiopian soldiers defeated Italian troops, thus being ...

.

[Carlton, Eric (1992), ''Occupation: The Policies and Practices of Military Conquerors''. Taylor & Francis. , pp. 88–89.][Vandervort, Bruce (1998), ''Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830–1914''. Indiana University Press. , p. 158.] A conquest of Ethiopia could also empower the cause of fascism and embolden its empire's rhetoric.

Ethiopia would also provide a bridge between Italy's Eritrean and

Italian Somaliland

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate and ...

possessions. Ethiopia's position in the League of Nations did not dissuade the Italians from invading in 1935; the "

collective security

Collective security is arrangement between states in which the institution accepts that an attack on one state is the concern of all and merits a collective response to threats by all. Collective security was a key principle underpinning the Lea ...

" envisaged by the League proved useless, and a scandal erupted when the

Hoare–Laval Pact

The Hoare–Laval Pact was an initially secret pact made in December of 1935 between French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval and British Foreign Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare for ending the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. Italy wanted to incorporate the i ...

revealed that Ethiopia's League allies were scheming to appease Italy.

Mobilisation

Following the

Welwel Incident

The Abyssinia Crisis, also known in Italy as the Walwal incident, was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in a dispute over the town of Walwal, which then turned into a conflict between Fascist Italy and the Ethiopian Empire (then com ...

of 5 December 1934, Selassie joined his northern armies and set up headquarters at

Desse in

Wollo

Wollo (Amharic: ወሎ) was a historical province of northern Ethiopia. During the Middle Ages this province name was Bete Amhara and it was the centre of the Solomonic emperors. Bete Amhara had an illustrious place in Ethiopian political and ...

province. He issued a generalized mobilization order on 3 October 1935. On 19 October 1935, he gave more precise orders for his army to his Commander-in-Chief, Ras

Kassa, instructing the men to choose hidden positions, to conserve ammunition, and to avoid wearing conspicuous clothing for fear of air attack. Compared to the Ethiopians, the Italians had an advanced, modern military that included a large air force. The Italians also came to employ

chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

throughout the conflict, even targeting

Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

field hospitals.

Progress of the war

Starting in early October 1935, the

Italians invaded Ethiopia. But, by November, the pace of invasion had slowed appreciably, and Selassie's northern armies were able to launch what was known as the "

Christmas Offensive

The Christmas Offensive took place during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian Offensive (military), offensive was more of a counteroffensive to an ever-slowing Fascist Italy, Italian De Bono's invasion of Abyssinia, offensive which sta ...

". During this offensive, the Italians were forced back in places and put on the defensive. In early 1936, the

First Battle of Tembien stopped the progress of the Ethiopian offensive and the Italians were ready to continue their offensive. Following the defeat and destruction of the northern Ethiopian armies at the

Battle of Amba Aradam

The Battle of Amba Aradam (also known as the Battle of Enderta) was fought on the northern front of what was known as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. This battle consisted of attacks and counter-attacks by Italian forces under Marshal of Italy ...

, the

Second Battle of Tembien, and the

Battle of Shire, Selassie took the field with the last Ethiopian army on the northern front. On 31 March 1936, he launched a

counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "Military exercise, war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objecti ...

against the Italians himself at the

Battle of Maychew

The Battle of Maychew () was the last major battle fought on the northern front during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. The battle consisted of a failed counterattack by the Ethiopian forces under Emperor Haile Selassie making frontal assaults ...

in southern

Tigray

The Tigray Region (or simply Tigray; officially the Tigray National Regional State) is the northernmost Regions of Ethiopia, regional state in Ethiopia. The Tigray Region is the homeland of the Tigrayan, Irob people, Irob and Kunama people. I ...

. The Emperor's army was defeated and retreated in disarray. As his army withdrew, the Italians attacked from the air along with rebellious Raya and Azebo tribesmen on the ground, who were armed and paid by the Italians. Many of the

Ethiopian military

The Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) () is the combined military force of Ethiopia. ENDF is consisted of 10 command forces which is controlled by the Chief of General Staff.

Commanders of the Military

Supreme Commander – Taye Ats ...

were obsolete compared to the invading Italian forces, being mostly untrained and possessing non-modern rifles and weaponry.

Selassie made a solitary

pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

to the churches at

Lalibela

Lalibela () is a town in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Located in the Lasta district and North Wollo Zone, it is a tourist site for its famous rock-cut monolithic churches designed in contrast to the earlier monolithic churches in Ethiopia ...

, at considerable risk of capture, before returning to his capital.

[.] After a stormy session of the council of state, it was agreed that because

Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

could not be defended, the government would relocate to the southern town of

Gore

Gore may refer to:

Places Australia

* Gore, Queensland

* Gore Creek (New South Wales)

* Gore Island (Queensland)

Canada

* Gore, Nova Scotia, a rural community

* Gore, Quebec, a township municipality

* Gore Bay, Ontario, a township on Manito ...

, and that in the interest of preserving the imperial house, Empress Menen Asfaw and the rest of the imperial family should immediately depart for

French Somaliland

French Somaliland (; ; ) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which became the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas. The Republic of Djibouti is its legal successor state.

History

French Somalil ...

, and from there continue on to

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

.

Exile debate

After further debate as to whether Selassie should go to Gore or accompany his family into exile, it was agreed that he should leave Ethiopia with his family and present the case of Ethiopia to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

at

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

. The decision was not unanimous and several participants, including the nobleman

Blatta

''Blatta'' is a genus of cockroaches. The name ''Blatta'' represents a specialised use of Latin ''blatta'', meaning a light-shunning insect.

Species

Species include:

* ''Blatta furcata'' (Karny, 1908)

* ''Blatta orientalis

The oriental cock ...

Tekle Wolde Hawariat

Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam (Amharic: ተክለ ሐዋርዓት ተክለ ማሪያም; June 1884 – April 1977) was an Ethiopian politician, an Amhara aristocrat and intellectual of the Japanizer school of thought. He was the primary au ...

, strenuously objected to the idea of an Ethiopian monarch fleeing before an invading force. Selassie appointed his cousin Ras

Imru Haile Selassie

Leul Ras Imru Haile Selassie, CBE (Amharic: ዕምሩ ኀይለ ሥላሴ; 23 November 1892 – 15 August 1980) was an Ethiopian noble, soldier, and diplomat. He served as acting Prime Minister for three days in 1960 during a coup d'éta ...

as Prince Regent in his absence, departing with his family for

French Somaliland

French Somaliland (; ; ) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which became the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas. The Republic of Djibouti is its legal successor state.

History

French Somalil ...

on 2 May 1936.

On 5 May, Marshal

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

led Italian troops into Addis Ababa, and Mussolini declared Ethiopia an Italian province.

Victor Emanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

was proclaimed as the new

Emperor of Ethiopia

The emperor of Ethiopia (, "King of Kings"), also known as the Atse (, "emperor"), was the hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Ethiopian Empire, from at least the 13th century until the abolition of the monarchy in 1975. The emperor w ...

. On the previous day, the Ethiopian exiles had left French Somaliland aboard the British cruiser

HMS ''Enterprise''. They were bound for

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

in the

British Mandate of Palestine, where the Ethiopian imperial family maintained a residence. The family disembarked at

Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

and then went on to Jerusalem. Once there, Selassie and his retinue prepared to make their case at Geneva. The choice of Jerusalem was highly symbolic, since the

Solomonic Dynasty claimed descent from the

House of David

The Davidic line refers to the descendants of David, who established the House of David ( ) in the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. In Judaism, the lineage is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible, as well as on later Jewish tradit ...

. Leaving the

Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

, Selassie and his entourage sailed aboard the British cruiser

HMS ''Capetown'' for

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, where he stayed at the

Rock Hotel. From Gibraltar, the exiles were transferred to an ordinary liner. By doing this, the United Kingdom government was spared the expense of a state reception.

Collective security and the League of Nations, 1936

On 12 May 1936, the League of Nations allowed Selassie to address the assembly. In response, Italy withdrew its League delegation. Although fluent in French, Selassie chose to deliver his speech in his native

Amharic

Amharic is an Ethio-Semitic language, which is a subgrouping within the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages. It is spoken as a first language by the Amhara people, and also serves as a lingua franca for all other metropolitan populati ...

. He asserted that Italy was employing

chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

on military and civilian targets alike.

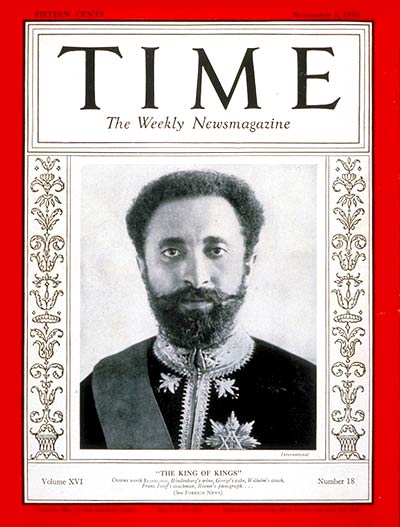

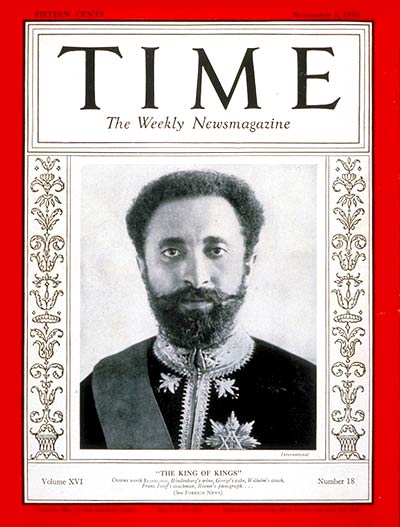

At the beginning of 1936, ''

Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' named Selassie "Man of the Year" for 1935, and his June 1936 speech made him an icon for anti-fascists around the world. He failed, however, to get the diplomatic and matériel support he needed. The League agreed to only partial sanctions on Italy, and Selassie was left without much-needed military equipment. Only six nations in 1937 did not recognise Italy's occupation: China, New Zealand, the Soviet Union, the Republic of Spain, Mexico and the United States.

Exile

Selassie spent his exile years (1936–1941) in

Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, England, in

Fairfield House, which he bought. The Emperor and

Kassa Haile Darge

'' Ras'' Kassa Hailu (Amharic: ካሣ ኀይሉ ዳርጌ; 7 August 1881 – 16 November 1956) was a Shewan Amhara nobleman, the son of Dejazmach Haile Wolde Kiros of Lasta, the ruling heir of Lasta's throne and younger brother of Emperor ...

took morning walks together behind the 14-room Victorian house's high walls. His favorite reading was "diplomatic history". It was during his exile in England that he began writing his 90,000-word autobiography.

Prior to Fairfield House, he briefly stayed at Warne's Hotel in

Worthing