Greenland East Coast 7 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an

, by Dale Mackenzie Brown, ''Archaeological Institute of America'', 28 February 2000 Greenland has been inhabited at intervals over at least the last 4,500 years by

The early Norse settlers named the island as ''Greenland.'' In the

The early Norse settlers named the island as ''Greenland.'' In the

. ''The Ancient Standard.'' 17 December 2010. The ''

From 986, Greenland's west coast was settled by

From 986, Greenland's west coast was settled by  Icelandic saga accounts of life in Greenland were composed in the 13th century and later, and do not constitute primary sources for the history of early Norse Greenland. Those accounts are closer to primary for more contemporaneous accounts of late Norse Greenland. Modern understanding therefore mostly depends on the physical data from archeological sites. Interpretation of

Icelandic saga accounts of life in Greenland were composed in the 13th century and later, and do not constitute primary sources for the history of early Norse Greenland. Those accounts are closer to primary for more contemporaneous accounts of late Norse Greenland. Modern understanding therefore mostly depends on the physical data from archeological sites. Interpretation of  Theories drawn from archeological excavations at

Theories drawn from archeological excavations at

In 1605–1607, King

In 1605–1607, King  After the Norse settlements died off, Greenland came under the de facto control of various Inuit groups, but the Danish government never forgot or relinquished the claims to Greenland that it had inherited from the Norse. When it re-established contact with Greenland in the early 17th century, Denmark asserted its sovereignty over the island. In 1721, a joint mercantile and clerical expedition led by Danish-Norwegian missionary

After the Norse settlements died off, Greenland came under the de facto control of various Inuit groups, but the Danish government never forgot or relinquished the claims to Greenland that it had inherited from the Norse. When it re-established contact with Greenland in the early 17th century, Denmark asserted its sovereignty over the island. In 1721, a joint mercantile and clerical expedition led by Danish-Norwegian missionary

When the union between the crowns of Denmark and Norway was dissolved in 1814, the

When the union between the crowns of Denmark and Norway was dissolved in 1814, the  During this war, the system of government changed:

During this war, the system of government changed:

In 1867,

In 1867,  In 1950, Denmark agreed to allow the US to regain the use of

In 1950, Denmark agreed to allow the US to regain the use of  This gave Greenland limited autonomy with its own legislature taking control of some internal policies, while the

This gave Greenland limited autonomy with its own legislature taking control of some internal policies, while the

Greenland is the world's largest non-continental island and the third largest area in North America after

Greenland is the world's largest non-continental island and the third largest area in North America after

", ''Ellensburg Daily Record'', 24 October 1951, p. 6. Retrieved 13 May 2012. This is disputed, but if it is so, they would be separated by narrow straits, reaching the sea at Ilulissat Icefjord, at

Greenland is home to two ecoregions:

Greenland is home to two ecoregions:  The terrestrial vertebrates of Greenland include the Greenland dog, which was introduced by the

The terrestrial vertebrates of Greenland include the Greenland dog, which was introduced by the  As of 2009, 269 species of fish from over 80 different families are known from the waters surrounding Greenland. Almost all are marine species with only a few in freshwater, notably

As of 2009, 269 species of fish from over 80 different families are known from the waters surrounding Greenland. Almost all are marine species with only a few in freshwater, notably

The Greenlandic government holds

The Greenlandic government holds

Greenland's

Greenland's

Greenland has a population of 56,421 (2021). In terms of country of birth, the population is estimated to be of 89.7% Greenlandic origin (

Greenland has a population of 56,421 (2021). In terms of country of birth, the population is estimated to be of 89.7% Greenlandic origin (

Both Greenlandic (an

Both Greenlandic (an

About 100 schools have been established. Greenlandic and Danish are taught there. Normally, Greenlandic is taught from kindergarten to the end of secondary school, but Danish is compulsory from the first cycle of primary school as a second language. As in Denmark with Danish, the school system provides for "Greenlandic 1" and "Greenlandic 2" courses. Language tests allow students to move from one level to the other. Based on the teachers' evaluation of their students, a third level of courses has been added: "Greenlandic 3". Secondary education in Greenland is generally vocational and technical. The system is governed by Regulation No. 16 of 28 October 1993 on Vocational and Technical Education, Scholarships and Career Guidance. Danish remains the main language of instruction. The capital, Nuuk, has a (bilingual) teacher training college and a (bilingual) university. At the end of their studies, all students must pass a test in the Greenlandic language.

Higher education is offered in Greenland: "university education" (regulation no. 3 of 9 May 1989); training of journalists, training of primary and lower secondary school teachers, training of social workers, training of social educators (regulation no. 1 of 16 May 1989); and training of nurses and nursing assistants (regulation no. 9 of 13 May 1990). Greenlandic students can continue their education in Denmark, if they wish and have the financial means to do so. For admission to Danish educational institutions, Greenlandic applicants are placed on an equal footing with Danish applicants.

About 100 schools have been established. Greenlandic and Danish are taught there. Normally, Greenlandic is taught from kindergarten to the end of secondary school, but Danish is compulsory from the first cycle of primary school as a second language. As in Denmark with Danish, the school system provides for "Greenlandic 1" and "Greenlandic 2" courses. Language tests allow students to move from one level to the other. Based on the teachers' evaluation of their students, a third level of courses has been added: "Greenlandic 3". Secondary education in Greenland is generally vocational and technical. The system is governed by Regulation No. 16 of 28 October 1993 on Vocational and Technical Education, Scholarships and Career Guidance. Danish remains the main language of instruction. The capital, Nuuk, has a (bilingual) teacher training college and a (bilingual) university. At the end of their studies, all students must pass a test in the Greenlandic language.

Higher education is offered in Greenland: "university education" (regulation no. 3 of 9 May 1989); training of journalists, training of primary and lower secondary school teachers, training of social workers, training of social educators (regulation no. 1 of 16 May 1989); and training of nurses and nursing assistants (regulation no. 9 of 13 May 1990). Greenlandic students can continue their education in Denmark, if they wish and have the financial means to do so. For admission to Danish educational institutions, Greenlandic applicants are placed on an equal footing with Danish applicants.

The nomadic

The nomadic

Today Greenlandic culture is a blending of traditional Inuit (

Today Greenlandic culture is a blending of traditional Inuit (

The national dish of Greenland is suaasat, a soup made from seal meat. Meat from marine mammals, game, birds, and fish play a large role in the Greenlandic diet. Due to the glacial landscape, most ingredients come from the ocean. Spices are seldom used besides salt and pepper. Greenlandic coffee is a "flaming" dessert coffee (set alight before serving) made with coffee, whiskey, Kahlúa, Grand Marnier, and whipped cream. It is stronger than the familiar Irish dessert coffee.

The national dish of Greenland is suaasat, a soup made from seal meat. Meat from marine mammals, game, birds, and fish play a large role in the Greenlandic diet. Due to the glacial landscape, most ingredients come from the ocean. Spices are seldom used besides salt and pepper. Greenlandic coffee is a "flaming" dessert coffee (set alight before serving) made with coffee, whiskey, Kahlúa, Grand Marnier, and whipped cream. It is stronger than the familiar Irish dessert coffee.

www.arcticyearbook.com/ay2013

* Sowa, F. 2014. ''Greenland.'' in: Hund, A. ''Antarctica and the Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth's Polar Regions.'' Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, pp. 312–316.

Greenland

entry at ''Denmark.dk''. *

The Government of Greenland Offices official website

Visit Greenland

nbsp;– the official Tourism in Greenland, Greenlandic Tourist Board

Inuit Circumpolar Council Greenland

{{Continental glaciations Greenland, Inuit territories Nordic countries Regions of the Arctic Dependent territories in North America Special territories of the European Union Island countries Members of the Nordic Council States and territories established in 1979 Danish dependencies Danish-speaking countries and territories Danish Realm Former Norwegian colonies Kingdom of Norway (872–1397) Christian states Northern America

island country

An island country, island state or an island nation is a country whose primary territory consists of one or more islands or parts of islands. Approximately 25% of all independent countries are island countries. Island countries are historically ...

in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm ( da, Danmarks Rige; fo, Danmarkar Ríki; kl, Danmarkip Naalagaaffik), officially the Kingdom of Denmark (; ; ), is a sovereign state located in Northern Europe and Northern North America. It consists of metropolitan Denma ...

. It is located between the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

and Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of ...

. Greenland is the world's largest island. It is one of three constituent countries that form the Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm ( da, Danmarks Rige; fo, Danmarkar Ríki; kl, Danmarkip Naalagaaffik), officially the Kingdom of Denmark (; ; ), is a sovereign state located in Northern Europe and Northern North America. It consists of metropolitan Denma ...

, along with Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

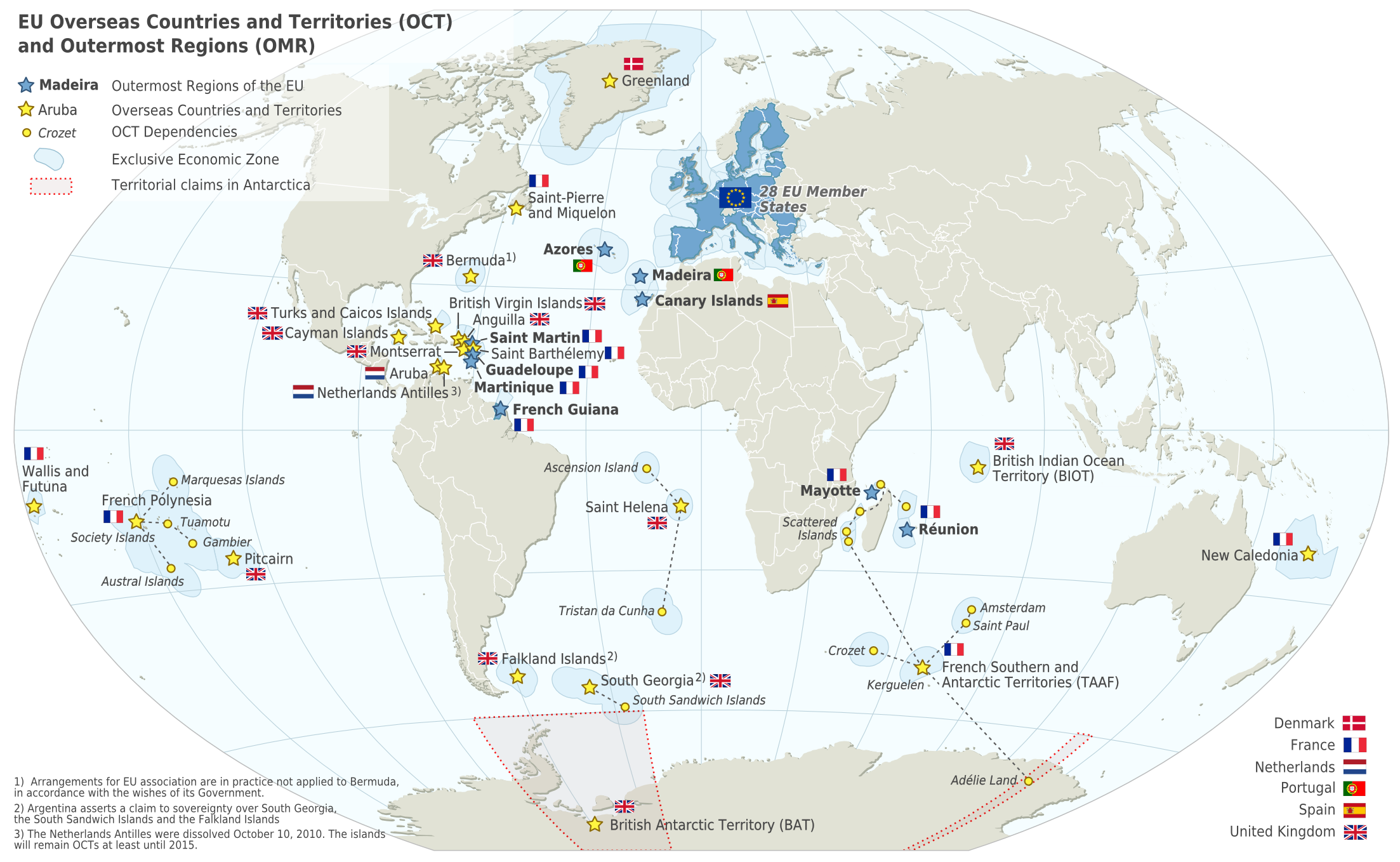

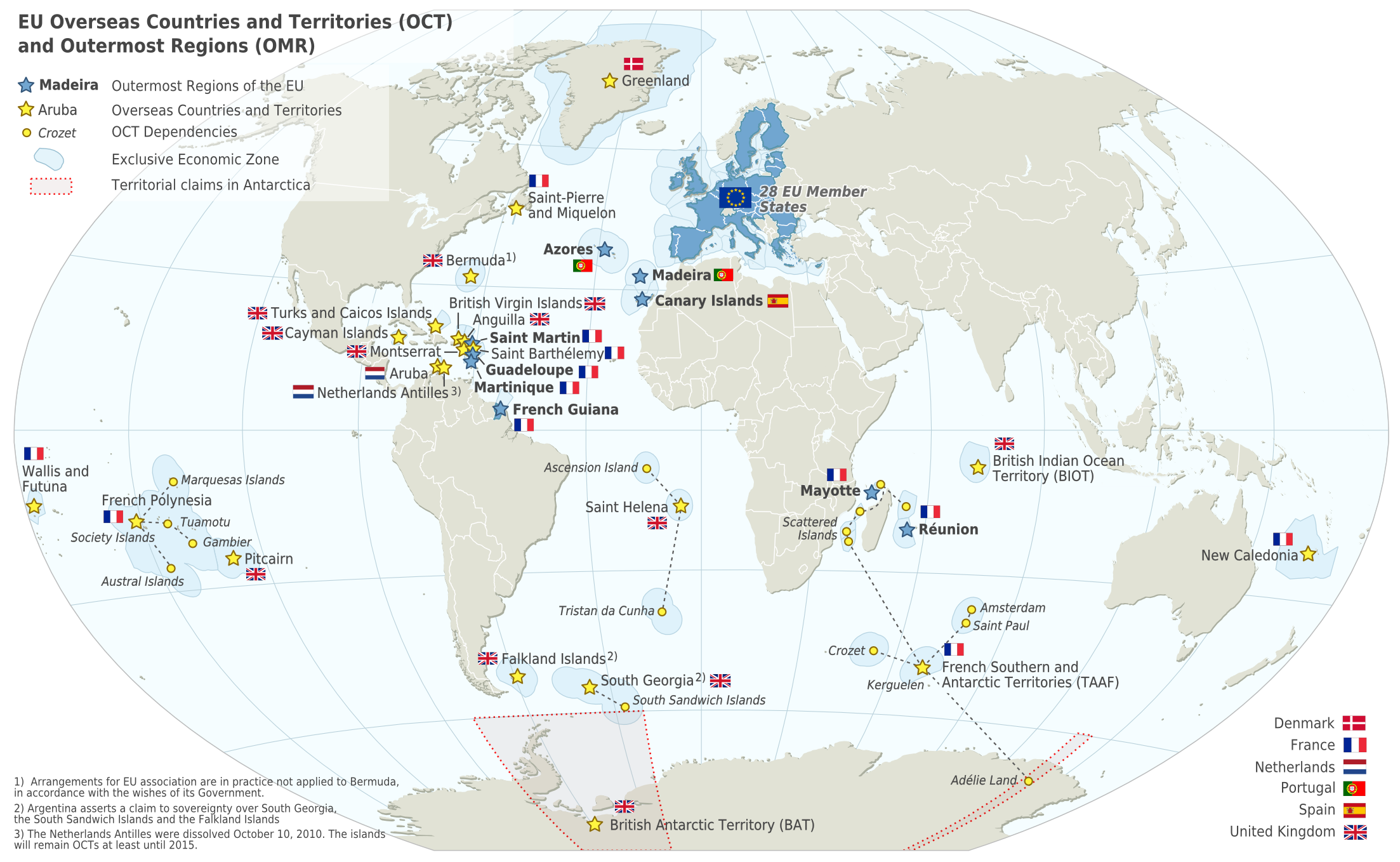

; the citizens of these countries are all citizens of Denmark and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

. Greenland's capital is Nuuk

Nuuk (; da, Nuuk, formerly ) is the capital and largest city of Greenland, a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark. Nuuk is the seat of government and the country's largest cultural and economic centre. The major cities from other coun ...

.

Though a part of the continent of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

(specifically Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

and Denmark, the colonial powers) for more than a millennium, beginning in 986

Year 986 ( CMLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* August 17 – Battle of the Gates of Trajan: Emperor Basil II leads a Byz ...

.The Fate of Greenland's Vikings, by Dale Mackenzie Brown, ''Archaeological Institute of America'', 28 February 2000 Greenland has been inhabited at intervals over at least the last 4,500 years by

Arctic peoples

Circumpolar peoples and Arctic peoples are umbrella terms for the various Indigenous peoples of the Arctic.

Prehistory

The earliest inhabitants of North America's central and eastern Arctic are referred to as the Arctic small tool tradition (AST ...

whose forebears migrated there from what is now Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the ...

settled the uninhabited southern part of Greenland beginning in the 10th century, having previously settled Iceland. Inuit arrived in the 13th century. Though under continuous influence of Norway and Norwegians, Greenland was not formally under the Norwegian crown until 1261. The Norse colonies disappeared in the late 15th century after Norway was hit by the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

and entered a severe decline.

In the early 17th century, Danish explorers reached Greenland again. Greenland became Danish in 1814 and was fully integrated in the Danish state in 1953 under the Constitution of Denmark

The Constitutional Act of the Realm of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Riges Grundlov), also known as the Constitutional Act of the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply the Constitution ( da, Grundloven, fo, Grundlógin, kl, Tunngaviusumik inatsit), is the c ...

. With the Constitution of 1953, the people in Greenland became citizens of Denmark. In 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the '' International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the '' Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the so ...

, Denmark granted home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wi ...

to Greenland; in 2008, Greenlanders voted in favour of the Self-Government Act, which transferred more power from the Danish government to the local Greenlandic government. Under the new structure, Greenland has gradually assumed responsibility for a number of governmental services and areas of competence. The Danish government still retains control of citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

, monetary policy and foreign affairs including defence. The majority of its residents are Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

. Today, the population is concentrated mainly on the southwest coast, while the rest of the island is sparsely populated. Three-quarters of Greenland is covered by the only permanent ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at La ...

outside of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. With a population of 56,081 (2020), it is the least densely populated region in the world. At 70%, Greenland has one of the highest shares of renewable energy in the world, mostly coming from hydropower

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of ...

.

Etymology

The early Norse settlers named the island as ''Greenland.'' In the

The early Norse settlers named the island as ''Greenland.'' In the Icelandic sagas

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

, the Norwegian-born Icelander Erik the Red

Erik Thorvaldsson (), known as Erik the Red, was a Norse explorer, described in medieval and Icelandic saga sources as having founded the first settlement in Greenland. He most likely earned the epithet "the Red" due to the color of his hair ...

was exiled from Iceland for manslaughter. Along with his extended family and his thrall

A thrall ( non, þræll, is, þræll, fo, trælur, no, trell, træl, da, træl, sv, träl) was a slave or serf in Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The corresponding term in Old English was . The status of slave (, ) contrasts wi ...

s (i.e. slaves or serfs), he set out in ships to explore an icy land known to lie to the northwest. After finding a habitable area and settling there, he named it ' (translated as "Greenland"), supposedly in the hope that the pleasant name would attract settlers."How Greenland got its name". ''The Ancient Standard.'' 17 December 2010. The ''

Saga of Erik the Red

The ''Saga of Erik the Red'', in non, Eiríks saga rauða (), is an Icelandic saga on the Norse exploration of North America. The original saga is thought to have been written in the 13th century. It is preserved in somewhat different version ...

'' states: "In the summer, Erik left to settle in the country he had found, which he called Greenland, as he said people would be attracted there if it had a favorable name."

The name of the country in the indigenous Greenlandic language

Greenlandic ( kl, kalaallisut, link=no ; da, grønlandsk ) is an Eskimo–Aleut language with about 56,000 speakers, mostly Greenlandic Inuit in Greenland. It is closely related to the Inuit languages in Canada such as Inuktitut. It is the m ...

is ("land of the Kalaallit").Stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Or ...

, p. 89 The Kalaallit

Kalaallit make up the largest group of the Greenlandic Inuit and are concentrated in Kitaa. It is also a contemporary term in the Greenlandic language for the indigenous people living in Greenland (Greenlandic ''Kalaallit Nunaat'').Hessel, 8 Th ...

are the indigenous Greenlandic Inuit

Greenlanders ( kl, Kalaallit / Tunumiit / Inughuit; da, Grønlændere) are people identified with Greenland or the indigenous people, the Greenlandic Inuit (''Grønlansk Inuit''; Kalaallit, Inughuit, and Tunumiit). This connection may be r ...

who inhabit the country's western region.

The military of the United States used as a code name for Greenland in World War II

The fall of Denmark in April 1940 left the Danish colony of Greenland an unoccupied territory of an occupied nation, under the possibility of seizure by the United Kingdom, United States or Canada. To forestall this, the United States acted to ...

, where they kept several bases named as ''Bluie (East or West) (sequential numeral)''.

History

Early Paleo-Inuit cultures

In prehistoric times, Greenland was home to several successive Paleo-Inuit cultures known today primarily through archaeological finds. The earliest entry of the Paleo-Inuit into Greenland is thought to have occurred about 2500 BC. From around 2500 BC to 800 BC, southern and western Greenland were inhabited by theSaqqaq culture

The Saqqaq culture (named after the Saqqaq settlement, the site of many archaeological finds) was a Paleo-Eskimo culture in southern Greenland. Up to this day, no other people seem to have lived in Greenland continually for as long as the Saqqaq ...

. Most finds of Saqqaq-period archaeological remains have been around Disko Bay

Disko Bay ( kl, Qeqertarsuup tunua; da, DiskobugtenChristensen, N.O. & al.Elections in Greenland. ''Arctic Circular'', Vol. 4 (1951), pp. 83–85. Op. cit. "Northern News". ''Arctic'', Vol. 5, No. 1 (Mar 1952), pp. 58–59.) is a large ...

, including the site of Saqqaq, after which the culture is named.

From 2400 BC to 1300 BC, the Independence I culture

Independence I was a culture of Paleo-Eskimos who lived in northern Greenland and the Canadian Arctic between 2400 and 1900 BC. There has been much debate among scholars on when Independence I culture disappeared, and, therefore, there is a margin ...

existed in northern Greenland. It was a part of the Arctic small tool tradition The Arctic Small Tool tradition (ASTt) was a broad cultural entity that developed along the Alaska Peninsula, around Bristol Bay, and on the eastern shores of the Bering Strait around 2500 BC. ASTt groups were the first human occupants of Arctic Ca ...

. Towns, including Deltaterrasserne, started to appear. Around 800 BC, the Saqqaq culture disappeared and the Early Dorset culture

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) in ...

emerged in western Greenland and the Independence II culture

Independence II was a Paleo-Eskimo culture that flourished in northern and northeastern Greenland from around 700 to 80 BC, north and south of the Independence Fjord. The Independence II culture existed in roughly the same areas of Greenland as t ...

in northern Greenland. The Dorset culture was the first culture to extend throughout the Greenlandic coastal areas, both on the west and east coasts. It lasted until the total onset of the Thule culture

The Thule (, , ) or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people o ...

in 1500 AD. The Dorset culture population lived primarily from hunting of whales

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

and caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

.

Norse settlement

From 986, Greenland's west coast was settled by

From 986, Greenland's west coast was settled by Icelanders

Icelanders ( is, Íslendingar) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland and speak Icelandic.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 AD when the Althing (Parliament) met f ...

and Norwegians

Norwegians ( no, nordmenn) are a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians a ...

, through a contingent of 14 boats led by Erik the Red. They formed three settlements – known as the Eastern Settlement

The Eastern Settlement ( non, Eystribygð ) was the first and by far the larger of the two main areas of Norse Greenland, settled by Norsemen from Iceland. At its peak, it contained approximately 4,000 inhabitants. The last written record from t ...

, the Western Settlement and the Middle Settlement

Ivittuut (formerly, Ivigtût) (Kalaallisut: "Grassy Place") is an abandoned mining town near Cape Desolation in southwestern Greenland, in the modern Sermersooq municipality on the ruins of the former Norse Middle Settlement.

Ivittuut is one ...

– on fjords near the southwesternmost tip of the island. They shared the island with the late Dorset culture inhabitants who occupied the northern and western parts, and later with the Thule culture that entered from the north. Norse Greenlanders submitted to Norwegian rule in 1261 under the Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

. Later the Kingdom of Norway entered into a personal union with Denmark in 1380 and from 1397 was a part of the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union ( Danish, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under a single monarch the three kingdo ...

.

The Norse settlements, such as Brattahlíð

Brattahlíð (), often anglicised as Brattahlid, was Erik the Red's estate in the Eastern Settlement Viking colony he established in south-western Greenland toward the end of the 10th century. The present settlement of Qassiarsuk, approximately ...

, thrived for centuries but disappeared sometime in the 15th century, perhaps at the onset of the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

. Apart from some runic inscriptions, the only contemporary records or historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians h ...

that survives from the Norse settlements is of their contact with Iceland or Norway. Medieval Norwegian sagas and historical works mention Greenland's economy as well as the bishops of Gardar and the collection of tithes. A chapter in the ''Konungs skuggsjá

''Konungs skuggsjá'' ( Old Norse for "King's mirror"; Latin: ''Speculum regale'', modern Norwegian: ''Kongsspegelen'' (Nynorsk) or ''Kongespeilet'' (Bokmål)) is a Norwegian didactic text in Old Norse from around 1250, an example of speculu ...

'' (''The King's Mirror'') describes Norse Greenland's exports and imports as well as grain cultivation.

Icelandic saga accounts of life in Greenland were composed in the 13th century and later, and do not constitute primary sources for the history of early Norse Greenland. Those accounts are closer to primary for more contemporaneous accounts of late Norse Greenland. Modern understanding therefore mostly depends on the physical data from archeological sites. Interpretation of

Icelandic saga accounts of life in Greenland were composed in the 13th century and later, and do not constitute primary sources for the history of early Norse Greenland. Those accounts are closer to primary for more contemporaneous accounts of late Norse Greenland. Modern understanding therefore mostly depends on the physical data from archeological sites. Interpretation of ice core

An ice core is a core sample that is typically removed from an ice sheet or a high mountain glacier. Since the ice forms from the incremental buildup of annual layers of snow, lower layers are older than upper ones, and an ice core contains ...

and clam shell data suggests that between 800 and 1300 AD the regions around the fjords of southern Greenland experienced a relatively mild climate several degrees Celsius higher than usual in the North AtlanticArnold C. (June 2010) "Cold did in the Norse," ''Earth Magazine''. p. 9. with trees and herbaceous plant

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition ...

s growing and livestock being farmed. Barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

was grown as a crop up to the 70th parallel. The ice cores indicate Greenland has had dramatic temperature shifts many times over the past 100,000 years. Similarly the Icelandic Book of Settlements records famines during the winters, in which "the old and helpless were killed and thrown over cliffs".

These Icelandic settlements vanished during the 14th and early 15th centuries. The demise of the Western Settlement coincides with a decrease in summer and winter temperatures. A study of North Atlantic seasonal temperature variability during the Little Ice Age showed a significant decrease in maximum summer temperatures beginning in the late 13th century to early 14th century – as much as lower than modern summer temperatures. The study also found that the lowest winter temperatures of the last 2,000 years occurred in the late 14th century and early 15th century. The Eastern Settlement was likely abandoned in the early to mid-15th century, during this cold period.

Herjolfsnes

Herjolfsnes was a Norse settlement in Greenland, 50 km northwest of Cape Farewell. It was established by Herjolf Bardsson in the late 10th century and is believed to have lasted some 500 years. The fate of its inhabitants, along with all ...

in the 1920s suggest that the condition of human bones from this period indicates that the Norse population was malnourished, possibly because of soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

resulting from the Norsemen's destruction of natural vegetation in the course of farming, turf-cutting, and wood-cutting. Malnutrition may also have resulted from widespread deaths from pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic disease with a stable number of in ...

plague; the decline in temperatures during the Little Ice Age; and armed conflicts with the ''Skræling

''Skræling'' (Old Norse and Icelandic: ''skrælingi'', plural ''skrælingjar'') is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the ...

s'' (Norse word for Inuit, meaning "wretches"). Recent archeological studies somewhat challenge the general assumption that the Norse colonization had a dramatic negative environmental effect on the vegetation. Data support traces of a possible Norse soil amendment strategy. More recent evidence suggests that the Norse, who never numbered more than about 2,500, gradually abandoned the Greenland settlements over the 15th century as walrus ivory, the most valuable export from Greenland, decreased in price because of competition with other sources of higher-quality ivory, and that there was actually little evidence of starvation or difficulties.

Other explanations of the disappearance of the Norse settlements have been proposed:

# Lack of support from the homeland.

# Ship-borne marauders (such as Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, English, or German pirates) rather than ''Skræling

''Skræling'' (Old Norse and Icelandic: ''skrælingi'', plural ''skrælingjar'') is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America (Canada and Greenland). In surviving sources, it is first applied to the ...

s'', could have plundered and displaced the Greenlanders.

# They were "the victims of hidebound thinking and of a hierarchical society dominated by the Church and the biggest land owners. In their reluctance to see themselves as anything but Europeans, the Greenlanders failed to adopt the kind of apparel that the Inuit employed as protection against the cold and damp or to borrow any of the Inuit hunting gear."

# That portion of the Greenlander population willing to adopt Inuit ways and means intermarried with and assimilated into the Inuit community. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, ''Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic'', 1938, chapter 1. Much of the Greenland population today is mixed Inuit and European ancestry. It was impossible in 1938 when Stefansson wrote his book to distinguish between intermarriage before the European loss of contact and after the contact was restored.

# "Norse society's structure created a conflict between the short-term interests of those in power, and the long-term interests of the society as a whole."

Thule culture (1300–present)

The Thule people are the ancestors of the current Greenlandic population. No genes from the Paleo-Inuit have been found in the present population of Greenland. The Thule culture migrated eastward from what is now known as Alaska around 1000 AD, reaching Greenland around 1300. The Thule culture was the first to introduce to Greenland such technological innovations asdog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing. Traditionally in Greenland and th ...

s and toggling harpoon

The toggling harpoon is an ancient weapon and tool used in whaling to impale a whale when thrown. Unlike earlier harpoon versions which had only one point, a toggling harpoon has a two-part point. One half of the point is firmly attached to the ...

s.

There is an account of contact and conflict with the Norse population, as told by the Inuit. It is republished in ''The Norse Atlantic Sagas'', by Gwyn Jones. Jones reports that there is also an account of perhaps the same incident, of more doubtful provenance, told by the Norse side.

1500–1814

In 1500, KingManuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate ( pt, O Venturoso), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portugal ...

sent Gaspar Corte-Real

Gaspar Corte-Real (1450–1501) was a Portuguese explorer who, alongside his father João Vaz Corte-Real and brother Miguel, participated in various exploratory voyages sponsored by the Portuguese Crown. These voyages are said to have been some o ...

to Greenland in search of a Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

to Asia which, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

, was part of Portugal's sphere of influence. In 1501, Corte-Real returned with his brother, Miguel Corte-Real

Miguel Corte-Real (; – 1502?) was a Portuguese explorer who charted about 600 miles of the coast of Labrador. In 1502, he disappeared while on an expedition and was believed to be lost at sea.

Early life

Miguel Corte-Real was a son of ...

. Finding the sea frozen, they headed south and arrived in Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. Upon the brothers' return to Portugal, the cartographic information supplied by Corte-Real was incorporated into a new map of the world which was presented to Ercole I d'Este

Ercole I d'Este KG (English: ''Hercules I''; 26 October 1431 – 25 January 1505) was Duke of Ferrara from 1471 until 1505. He was a member of the House of Este. He was nicknamed ''North Wind'' and ''The Diamond''.

Biography

Ercole was born i ...

, Duke of Ferrara

Emperor Frederick III conferred Borso d'Este, Lord of Ferrara, with the Duchy of Modena and Reggio in 1452, while Pope Paul II formally elevated him in 1471 as Duke of Ferrara, over which the family had in fact long presided. This latter territ ...

, by Alberto Cantino in 1502. The ''Cantino'' planisphere, made in Lisbon, accurately depicts the southern coastline of Greenland.

In 1605–1607, King

In 1605–1607, King Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years, 330 days is the longest of Danish monarchs and Scandinavian mona ...

sent a series of expeditions to Greenland and Arctic waterways to locate the lost eastern Norse settlement and assert Danish sovereignty over Greenland. The expeditions were mostly unsuccessful, partly due to leaders who lacked experience with the difficult Arctic ice and weather conditions, and partly because the expedition leaders were given instructions to search for the Eastern Settlement on the east coast of Greenland just north of Cape Farewell, which is almost inaccessible due to southward drifting ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fastene ...

. The pilot on all three trips was English explorer James Hall.

After the Norse settlements died off, Greenland came under the de facto control of various Inuit groups, but the Danish government never forgot or relinquished the claims to Greenland that it had inherited from the Norse. When it re-established contact with Greenland in the early 17th century, Denmark asserted its sovereignty over the island. In 1721, a joint mercantile and clerical expedition led by Danish-Norwegian missionary

After the Norse settlements died off, Greenland came under the de facto control of various Inuit groups, but the Danish government never forgot or relinquished the claims to Greenland that it had inherited from the Norse. When it re-established contact with Greenland in the early 17th century, Denmark asserted its sovereignty over the island. In 1721, a joint mercantile and clerical expedition led by Danish-Norwegian missionary Hans Egede

Hans Poulsen Egede (31 January 1686 – 5 November 1758) was a Dano-Norwegian Lutheran missionary who launched mission efforts to Greenland, which led him to be styled the Apostle of Greenland. He established a successful mission among the Inui ...

was sent to Greenland, not knowing whether a Norse civilization remained there. This expedition is part of the Dano-Norwegian colonization of the Americas. After 15 years in Greenland, Hans Egede left his son Paul Egede in charge of the mission there and returned to Denmark, where he established a Greenland Seminary. This new colony was centred at Godthåb

Nuuk (; da, Nuuk, formerly ) is the capital and largest city of Greenland, a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark. Nuuk is the seat of government and the country's largest cultural and economic centre. The major cities from other coun ...

("Good Hope") on the southwest coast. Gradually, Greenland was opened up to Danish merchants, but closed to those from other countries.

Treaty of Kiel to World War II

When the union between the crowns of Denmark and Norway was dissolved in 1814, the

When the union between the crowns of Denmark and Norway was dissolved in 1814, the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on t ...

severed Norway's former colonies and left them under the control of the Danish monarch. Norway occupied then-uninhabited eastern Greenland as Erik the Red's Land in July 1931, claiming that it constituted ''terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

It was a principle sometimes used in international law to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it.

:

:

...

''. Norway and Denmark agreed to submit the matter in 1933 to the Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

, which decided against Norway.

Greenland's connection to Denmark was severed on 9 April 1940, early in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, after Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. On 8 April 1941, the United States occupied Greenland to defend it against a possible invasion by Germany. The United States occupation of Greenland continued until 1945. Greenland was able to buy goods from the United States and Canada by selling cryolite

Cryolite ( Na3 Al F6, sodium hexafluoroaluminate) is an uncommon mineral identified with the once-large deposit at Ivittuut on the west coast of Greenland, mined commercially until 1987.

History

Cryolite was first described in 1798 by Danish vete ...

from the mine at Ivittuut

Ivittuut (formerly, Ivigtût) (Kalaallisut: "Grassy Place") is an abandoned mining town near Cape Desolation in southwestern Greenland, in the modern Sermersooq municipality on the ruins of the former Norse Middle Settlement.

Ivittuut is one o ...

. The major air bases were Bluie West-1 at Narsarsuaq

Narsarsuaq (lit. ''Great Plan'';''Facts and History of Narsarsuaq'', Narsarsuad Tourist Information old spelling: ''Narssarssuaq'') is a settlement in the Kujalleq municipality in southern Greenland. It had 123 inhabitants in 2020. There is a thri ...

and Bluie West-8

Sondrestrom Air Base, originally Bluie West-8, was a United States Air Force base in central Greenland. The site is located north of the Arctic Circle and from the northeast end of Kangerlussuaq Fjord (formerly known by its Danish name ''Sønd ...

at Søndre Strømfjord (Kangerlussuaq), both of which are still used as Greenland's major international airports. Bluie

Bluie was the United States military code name for Greenland during World War II. It is remembered by the numbered sequence of base locations identified by the 1941 United States Coast Guard South Greenland Survey Expedition, and subsequently us ...

was the military code name for Greenland.

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Eske Brun

Eske Brun (May 25, 1904 – October 11, 1987) was a high civil servant in Greenland and in relation to Greenland from 1932 to 1964.

Early life and career.

Eske Brun was born in Aalborg in the northern part of Jutland, Denmark. Eske Brun was b ...

ruled the island under a law of 1925 that allowed governors to take control under extreme circumstances; Governor Aksel Svane was transferred to the United States to lead the commission to supply Greenland. The Danish Sirius Patrol guarded the northeastern shores of Greenland in 1942 using dog sleds. They detected several German weather station

A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for measuring atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include tempera ...

s and alerted American troops, who destroyed the facilities. After the collapse of the Third Reich, Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, h ...

briefly considered escaping in a small aeroplane to hide out in Greenland, but changed his mind and decided to surrender to the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

.

Greenland had been a protected and very isolated society until 1940. The Danish government

The Cabinet of Denmark ( da, regering) has been the chief executive body and the government of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1848. The Cabinet is led by the Prime Minister. There are around 25 members of the Cabinet, known as "ministers", all of wh ...

had maintained a strict monopoly of Greenlandic trade, allowing no more than small scale barter trading with British whalers. In wartime Greenland developed a sense of self-reliance through self-government and independent communication with the outside world. Despite this change, in 1946 a commission including the highest Greenlandic council, the '' Landsrådene'', recommended patience and no radical reform of the system. Two years later, the first step towards a change of government was initiated when a grand commission was established. A final report (G-50) was presented in 1950, which recommended the introduction of a modern welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

with Denmark's development as sponsor and model. In 1953, Greenland was made an equal part of the Danish Kingdom. Home rule was granted in 1979.

Home rule and self-rule

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

worked with former senator Robert J. Walker to explore the possibility of buying Greenland and, perhaps, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. Opposition in Congress ended this project. Following World War II, the United States developed a geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

interest in Greenland, and in 1946 the United States offered to buy the island from Denmark for $100,000,000. Denmark refused to sell it. In the 21st century, the United States remains interested in investing in the resource base of Greenland and in tapping hydrocarbons off the Greenlandic coast. In August 2019, the US again proposed to buy the country, prompting premier Kim Kielsen

Kim Kielsen (born 30 November 1966) is a Greenlandic politician, who served as leader of the Siumut party and sixth prime minister of Greenland between 2014 and 2021.

Careers Past careers

Kielsen was originally a mariner, and then a police offi ...

to issue the statement, "Greenland is not for sale and cannot be sold, but Greenland is open for trade and cooperation with other countries — including the United States."

In 1950, Denmark agreed to allow the US to regain the use of

In 1950, Denmark agreed to allow the US to regain the use of Thule Air Base

Thule Air Base (pronounced or , kl, Qaanaaq Mitarfik, da, Thule Lufthavn), or Thule Air Base/Pituffik Airport , is the United States Space Force's northernmost base, and the northernmost installation of the U.S. Armed Forces, located north ...

; it was greatly expanded between 1951 and 1953 as part of a unified NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

defence strategy. The local population of three nearby villages was moved more than away in the winter. The United States tried to construct a subterranean network of secret nuclear missile launch sites in the Greenlandic ice cap, named Project Iceworm. According to documents declassified in 1996, this project was managed from Camp Century

Camp Century was an Arctic United States military scientific research base in Greenland. situated 240 km (150 miles) east of Thule Air Base. When built, Camp Century was publicized as a demonstration for affordable ice-cap military outposts ...

from 1960 to 1966 before abandonment as unworkable. The missiles were never fielded, and necessary consent from the Danish Government to do so was never sought. The Danish government did not become aware of the programme's mission until 1997, when they discovered it while looking, in the declassified documents, for records related to the crash

Crash or CRASH may refer to:

Common meanings

* Collision, an impact between two or more objects

* Crash (computing), a condition where a program ceases to respond

* Cardiac arrest, a medical condition in which the heart stops beating

* Couch ...

of a nuclear equipped B-52

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

bomber at Thule in 1968.

With the 1953 Danish constitution, Greenland's colonial status ended as the island was incorporated into the Danish realm as an amt

Amt is a type of administrative division governing a group of municipalities, today only in Germany, but formerly also common in other countries of Northern Europe. Its size and functions differ by country and the term is roughly equivalent to ...

(county). Danish citizenship was extended to Greenlanders. Danish policies toward Greenland consisted of a strategy of cultural assimilation — or de-Greenlandification. During this period, the Danish government promoted the exclusive use of the Danish language in official matters, and required Greenlanders to go to Denmark for their post-secondary education. Many Greenlandic children grew up in boarding schools in southern Denmark, and a number lost their cultural ties to Greenland. While the policies "succeeded" in the sense of shifting Greenlanders from being primarily subsistence hunters into being urbanized wage earners, the Greenlandic elite began to reassert a Greenlandic cultural identity. A movement developed in favour of independence, reaching its peak in the 1970s. As a consequence of political complications in relation to Denmark's entry into the European Common Market in 1972, Denmark began to seek a different status for Greenland, resulting in the Home Rule Act of 1979.

This gave Greenland limited autonomy with its own legislature taking control of some internal policies, while the

This gave Greenland limited autonomy with its own legislature taking control of some internal policies, while the Parliament of Denmark

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature ( parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark— Denmark proper together with the Faroe Island ...

maintained full control of external policies, security, and natural resources. The law came into effect on 1 May 1979. The Queen of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland. The Kingdom of Denmark was ...

, Margrethe II, remains Greenland's head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

. In 1985, Greenland left the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

(EEC) upon achieving self-rule, as it did not agree with the EEC's commercial fishing regulations and an EEC ban on seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

skin products. Greenland voters approved a referendum on greater autonomy on 25 November 2008. According to one study, the 2008 vote created what "can be seen as a system between home rule and full independence."

On 21 June 2009, Greenland gained self-rule with provisions for assuming responsibility for self-government of judicial affairs, policing, and natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

s. Also, Greenlanders were recognized as a separate people under international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

. Denmark maintains control of foreign affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy a ...

and defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

matters. Denmark upholds the annual block grant of 3.2 billion Danish kroner, but as Greenland begins to collect revenues of its natural resources, the grant will gradually be diminished. This is generally considered to be a step toward eventual full independence from Denmark. Greenlandic was declared the sole official language of Greenland at the historic ceremony.

Tourism

Tourism increased significantly between 2015 and 2019, with the number of visitors increasing from 77,000 per year to 105,000. One source estimated that in 2019 the revenue from this aspect of the economy was about 450 million kroner (US$67 million). Like many aspects of the economy, this slowed dramatically in 2020, and into 2021, due to restrictions required as a result of theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

; one source describes it as being the "biggest economic victim of the coronavirus" (the overall economy did not suffer too severely as of mid-2020, thanks to the fisheries "and a hefty subsidy from Copenhagen"). Greenland's goal for returning tourism is to develop it "right" and to "build a more sustainable tourism for the long run".

Geography and climate

Greenland is the world's largest non-continental island and the third largest area in North America after

Greenland is the world's largest non-continental island and the third largest area in North America after Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. It is between latitudes 59° and 83°N, and longitudes 11° and 74°W. Greenland is bordered by the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

to the north, the Greenland Sea

The Greenland Sea is a body of water that borders Greenland to the west, the Svalbard archipelago to the east, Fram Strait and the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Norwegian Sea and Iceland to the south. The Greenland Sea is often defined a ...

to the east, the North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to the southeast, the Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The strait was named for the English explorer John ...

to the southwest, Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

to the west, the Nares Strait

, other_name =

, image = Map indicating Nares Strait.png

, alt =

, caption = Nares Strait (boxed) is between Ellesmere Island and Greenland.

, image_bathymetry =

, alt_bathymetry ...

and Lincoln Sea

Lincoln Sea (french: Mer de Lincoln; da, Lincolnhavet) is a body of water in the Arctic Ocean, stretching from Cape Columbia, Canada, in the west to Cape Morris Jesup, Greenland, in the east. The northern limit is defined as the great circle lin ...

to the northwest. The nearest countries to Greenland are Canada, to the west and southwest across Nares Strait and Baffin Bay, as well as a shared border on Hans Island; and Iceland, southeast of Greenland in the Atlantic Ocean. Greenland also contains the world's largest national park, and it is the largest

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms (o ...

dependent territory

A dependent territory, dependent area, or dependency (sometimes referred as an external territory) is a territory that does not possess full political independence or sovereignty as a sovereign state, yet remains politically outside the controll ...

by area in the world, as well as the fourth largest country subdivision in the world, after Sakha Republic

Sakha, officially the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia),, is the largest republic of Russia, located in the Russian Far East, along the Arctic Ocean, with a population of roughly 1 million. Sakha comprises half of the area of its governing Far E ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

's state of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

, and Russia's Krasnoyarsk Krai

Krasnoyarsk Krai ( rus, Красноя́рский край, r=Krasnoyarskiy kray, p=krəsnɐˈjarskʲɪj ˈkraj) is a federal subject of Russia (a krai), with its administrative center in the city of Krasnoyarsk, the third-largest city in Si ...

, and the largest in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

.

The lowest temperature ever recorded in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

was recorded in Greenland, near the topographic summit of the Greenland Ice Sheet

The Greenland ice sheet ( da, Grønlands indlandsis, kl, Sermersuaq) is a vast body of ice covering , roughly near 80% of the surface of Greenland. It is sometimes referred to as an ice cap, or under the term ''inland ice'', or its Danish equi ...

, on 22 December 1991, when the temperature reached . In Nuuk, the average daily temperature varies over the seasons from The total area of Greenland is (including other offshore minor islands), of which the Greenland ice sheet

The Greenland ice sheet ( da, Grønlands indlandsis, kl, Sermersuaq) is a vast body of ice covering , roughly near 80% of the surface of Greenland. It is sometimes referred to as an ice cap, or under the term ''inland ice'', or its Danish equi ...

covers (81%) and has a volume of approximately . The highest point on Greenland is Gunnbjørn Fjeld

Gunnbjørn Fjeld is the tallest mountain in Greenland, the Kingdom of Denmark, and north of the Arctic Circle. It is a nunatak, a rocky peak protruding through glacial ice.

Geography

Gunnbjørn Fjeld is located in the Watkins Range, an area o ...

at of the Watkins Range

The Watkins Range ( da, Watkins Bjerge) is Greenland's highest mountain range. It is located in King Christian IX Land, Sermersooq municipality.

The range was named after British Arctic explorer Gino Watkins.

History

Made up entirely of nuna ...

(East Greenland mountain range The East Greenland orogen, also known as East Greenland mountain range, is the linear mountain range along the eastern Greenland coast, from 70 to 82 degrees north latitude.

Geologically, the mountain chain consists of Silurian to early Devon ...

). The majority of Greenland, however, is less than in elevation.

The weight of the ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at La ...

has depressed the central land area to form a basin lying more than below sea level,DK Atlas, 2001. while elevations rise suddenly and steeply near the coast.

The ice flows generally to the coast from the centre of the island. A survey led by French scientist Paul-Emile Victor in 1951 concluded that, under the ice sheet, Greenland is composed of three large islands.Find Greenland Icecap Bridges Three Islands", ''Ellensburg Daily Record'', 24 October 1951, p. 6. Retrieved 13 May 2012. This is disputed, but if it is so, they would be separated by narrow straits, reaching the sea at Ilulissat Icefjord, at

Greenland's Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon of Greenland is a tentative canyon of record length discovered underneath the Greenland ice sheet as reported in the journal ''Science'' on 30 August 2013 (submitted 29 April 2013), by scientists from the University of Bristol, ...

and south of Nordostrundingen

Nordostrundingen (corrupted from da, Nordøstrundingen which means Northeastern rounding, in English Northeast Foreland), is a headland located at the northeastern end of Greenland. Administratively it is part of the Northeast Greenland National ...

.

All towns and settlements of Greenland are situated along the ice-free coast, with the population being concentrated along the west coast. The northeastern part of Greenland is not part of any municipality, but it is the site of the world's largest national park, Northeast Greenland National Park

Northeast Greenland National Park ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaanni nuna eqqissisimatitaq, da, Grønlands Nationalpark) is the world's largest national park and the 10th largest protected area (the only larger protected areas all consist mostly of sea) ...

.

At least four scientific expedition stations and camps had been established on the ice sheet in the ice-covered central part of Greenland (indicated as pale blue in the adjacent map): Eismitte, North Ice, North GRIP Camp and The Raven Skiway. There is a year-round station Summit Camp

Summit Camp, also Summit Station, is a year-round staffed research station near the apex of the Greenland ice sheet. The station is located at above sea level. The population of the station is typically five in wintertime and reaches a maximu ...

on the ice sheet, established in 1989. The radio station Jørgen Brønlund Fjord

Jørgen Brønlund Fjord or Bronlund Fjord is a fjord in southern Peary Land, northern Greenland.

It was named after polar explorer Jørgen Brønlund by the Danmark expedition.

Geography

It runs roughly from NW to SE with its mouth located at t ...

was, until 1950, the northernmost permanent outpost in the world.

The extreme north of Greenland, Peary Land, is not covered by an ice sheet, because the air there is too dry to produce snow, which is essential in the production and maintenance of an ice sheet. If the Greenland ice sheet were to melt away completely, the world's sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardis ...

would rise by more than .

In 2003, a small island, in length and width, was discovered by arctic explorer Dennis Schmitt

Dennis Schmitt (born May 23, 1946) is a veteran explorer, adventurer and composer.

Early life

Schmitt grew up in Berkeley, California, the son of mixed German and American parentage. His father was a plumber. Displaying early aptitude with lang ...

and his team at the coordinates of 83-42. Whether this island is permanent is not yet confirmed. If it is, it is the northernmost permanent known land on Earth.

In 2007, the existence of a new island was announced. Named "Uunartoq Qeqertaq

Uunartoq Qeqertaq ( Greenlandic), ''Warming Island'' in English, is an island off the east central coast of Greenland, north of the Arctic Circle. It became recognised as an island only in September 2005, by US explorer Dennis Schmitt. It was at ...

" (English: ''Warming Island''), this island has always been present off the coast of Greenland, but was covered by a glacier. This glacier was discovered in 2002 to be shrinking rapidly, and by 2007 had completely melted away, leaving the exposed island. The island was named Place of the Year by the Oxford Atlas of the World in 2007. Ben Keene, the atlas's editor, commented:

Some controversy surrounds the history of the island, specifically over whether the island might have been revealed during a brief warm period in Greenland during the mid-20th century.

Climate change

Between 1989 and 1993, U.S. and Europeanclimate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologi ...

researchers drilled into the summit of Greenland's ice sheet, obtaining a pair of long ice core

An ice core is a core sample that is typically removed from an ice sheet or a high mountain glacier. Since the ice forms from the incremental buildup of annual layers of snow, lower layers are older than upper ones, and an ice core contains ...

s. Analysis of the layering and chemical composition of the cores has provided a revolutionary new record of climate change in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

going back about 100,000 years and illustrated that the world's weather and temperature have often shifted rapidly from one seemingly stable state to another, with worldwide consequences

Consequence may refer to:

* Logical consequence, also known as a ''consequence relation'', or ''entailment''

* In operant conditioning, a result of some behavior

* Consequentialism, a theory in philosophy in which the morality of an act is determi ...

. The glaciers of Greenland are also contributing to a rise in the global sea level faster than was previously believed. Between 1991 and 2004, monitoring of the weather at one location (Swiss Camp) showed that the average winter temperature had risen almost . Other research has shown that higher snowfalls from the North Atlantic oscillation caused the interior of the ice cap to thicken by an average of each year between 1994 and 2005.

In July 2021, Greenland banned all new oil and gas exploration in its territory, with government officials stating that the environmental "price of oil

The price of oil, or the oil price, generally refers to the spot price of a barrel () of benchmark crude oil—a reference price for buyers and sellers of crude oil such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Brent Crude, Dubai Crude, OPEC ...

extraction is too high."

In August 2021, rain fell on the summit of Greenland's ice cap for the first time in recorded history, which scientists attributed to climate change.

Geology

The island was part of the very ancient Precambrian continent ofLaurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, althoug ...

, the eastern core of which forms the Greenland Shield, while the less exposed coastal strips become a plateau. On these ice-free coastal strips are sediments formed in the Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

, overprinted by metamorphism and now formed by glaciers, which continue into the Cenozoic and Mesozoic in parts of the island.

In the east and west of Greenland there are remnants of flood basalts

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of ...

. Notable rock provinces (metamorphic

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock (protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, causi ...

igneous rocks, ultramafics, and anorthosites) are found on the southwest coast at Qeqertarsuatsiaat. East of Nuuk, the banded iron ore region of Isukasia, over three billion years old, contains the world's oldest rocks, such as greenlandite (a rock composed predominantly of hornblende and hyperthene), formed 3.8 billion years ago, and nuummite. In southern Greenland, the Illimaussaq alkaline complex consists of pegmatites