Guns, Germs and Steel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies'' (subtitled ''A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years'' in Britain) is a 1997

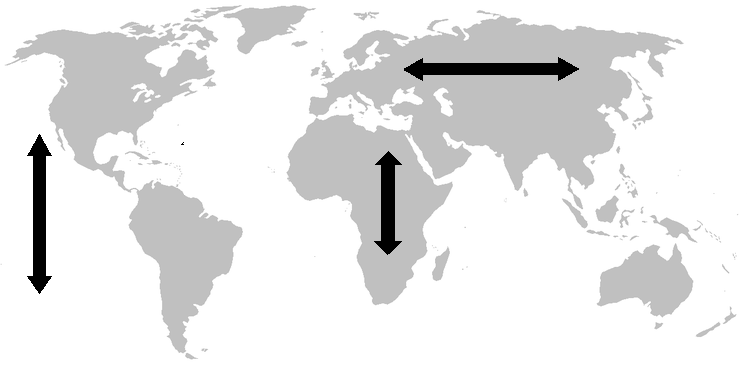

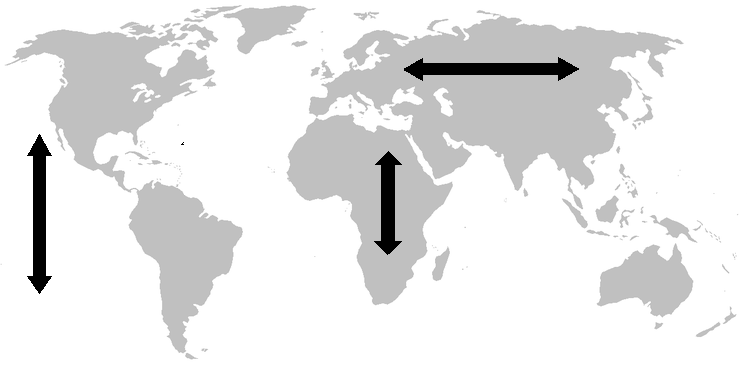

Eurasia's large landmass and long east–west distance increased these advantages. Its large area provided more plant and animal species suitable for domestication. Equally important, its east–west orientation has allowed groups of people to wander and empires to conquer from one end of the continent to the other while staying at the same latitude. This was important because similar climate and cycle of seasons let them keep the same "food production system" – they could keep growing the same crops and raising the same animals all the way from Scotland to Siberia. Doing this throughout history, they spread innovations, languages and diseases everywhere.

By contrast, the north–south orientation of the Americas and Africa created countless difficulties adapting crops domesticated at one

Eurasia's large landmass and long east–west distance increased these advantages. Its large area provided more plant and animal species suitable for domestication. Equally important, its east–west orientation has allowed groups of people to wander and empires to conquer from one end of the continent to the other while staying at the same latitude. This was important because similar climate and cycle of seasons let them keep the same "food production system" – they could keep growing the same crops and raising the same animals all the way from Scotland to Siberia. Doing this throughout history, they spread innovations, languages and diseases everywhere.

By contrast, the north–south orientation of the Americas and Africa created countless difficulties adapting crops domesticated at one

Anthropologist Kerim Friedman wrote, "While it is interesting and important to ask why technologies developed in some countries as opposed to others, I think it overlooks a fundamental issue: the inequality within countries as well as between them." Timothy Burke, an instructor in African history at

''Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies''

. Retrieved September 21, 2015. The

PBS

nbsp;– ''Guns, Germs, and Steel''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Guns, Germs, And Steel 1997 non-fiction books 20th-century history books Books about cultural geography Environmental non-fiction books Eurasian history European colonization of the Americas History books about agriculture History books about civilization Non-fiction books about Indigenous peoples of the Americas Non-fiction books adapted into films Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction–winning works W. W. Norton & Company books Works about the theory of history Works by Jared Diamond World history

transdisciplinary

Transdisciplinarity is an approach that iteratively interweaves knowledge systems, skills, methodologies, values and fields of expertise within inclusive and innovative collaborations that bridge academic disciplines and community perspectives, ...

nonfiction book by the American author Jared Diamond

Jared Mason Diamond (born September 10, 1937) is an American scientist, historian, and author. In 1985 he received a MacArthur Genius Grant, and he has written hundreds of scientific and popular articles and books. His best known is '' Guns, G ...

. The book attempts to explain why Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

n and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

n civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

, moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop where the outcome of a process reinforces the inciting process to build momentum. As such, these forces can exacerbate the effects ...

loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians (for example, written language

A written language is the representation of a language by means of writing. This involves the use of visual symbols, known as graphemes, to represent linguistic units such as phonemes, syllables, morphemes, or words. However, written language is ...

or the development among Eurasians of resistance to endemic disease

In epidemiology, an infection is said to be endemic in a specific population or populated place when that infection is constantly present, or maintained at a baseline level, without extra infections being brought into the group as a result of tr ...

s), he asserts that these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on societies and cultures (for example, by facilitating commerce and trade between different cultures) and were not inherent in the Eurasian genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

s.

In 1998, it won the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for general nonfiction and the Aventis Prize for Best Science Book. A documentary based on the book, and produced by the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

, was broadcast on PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

in July 2005.

Synopsis

The prologue opens with an account of Diamond's conversation with Yali, aPapua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an island country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean n ...

n politician. The conversation turned to the differences in power and technology between Papua New Guineans and the Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

ans who dominated the region for two centuries, differences that neither of them considered due to European genetic superiority. Yali asked, using the local term ''cargo

In transportation, cargo refers to goods transported by land, water or air, while freight refers to its conveyance. In economics, freight refers to goods transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. The term cargo is also used in cas ...

'' for inventions and manufactured goods, "Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own?"

Diamond realized the same question seemed to apply elsewhere: "People of Eurasian origin... dominate... the world in wealth and power." Other peoples, after having thrown off colonial domination, still lag in wealth and power. Still others, he says, "have been decimated, subjugated, and in some cases even exterminated by European colonialists."

The peoples of other continents ( sub-Saharan Africans, Indigenous people of the Americas

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples comprise the two continents' pre-Columbian inhabitants, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with them in the 15th century, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with the pre-Columbian population of ...

, Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia (co ...

, New Guineans, and the original inhabitants of tropical Southeast Asia) have been largely conquered, displaced and in some extreme cases – referring to Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians, and South Africa's indigenous Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

peoples – largely exterminated by farm-based societies such as Eurasians and Bantu. He believes this is due to these societies' technological and immunological advantages, stemming from the early rise of agriculture after the last ice age.

Title

The book's title is a reference to the means by which farm-based societies conquered populations and maintained dominance though sometimes being vastly outnumbered, so that imperialism was enabled by guns, germs, and steel. Diamond argues geographic, climatic and environmental characteristics which favored early development of stable agricultural societies ultimately led to immunity to diseases endemic in agricultural animals and the development of powerful, organizedstates

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

capable of dominating others.

Summary

Diamond argues that Eurasiancivilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

is not so much a product of ingenuity, but of opportunity and necessity. That is, civilization is not created out of superior intelligence, but is the result of a chain of developments, each made possible by certain preconditions.

The first step towards civilization is the move from nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

to rooted agrarian society. Several conditions are necessary for this transition to occur: access to high-carbohydrate vegetation that endures storage; a climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

dry enough to allow storage; and access to animals docile enough for domestication

Domestication is a multi-generational Mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a st ...

and versatile enough to survive captivity. Control of crops

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. In other words, a crop is a plant or plant product that is grown for a specific purpose such as food, fibre, or fuel.

When plants of the same species a ...

and livestock leads to food surpluses. Surpluses free people to specialize in activities other than sustenance and support population growth. The combination of specialization and population growth leads to the accumulation of social and technological innovations which build on each other. Large societies develop ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society.

In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the class who own the means of production in a given society and apply ...

es and supporting bureaucracies, which in turn lead to the organization of nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

s and empires.

Although agriculture arose in several parts of the world, Eurasia gained an early advantage due to the greater availability of suitable plant and animal species for domestication. In particular, Eurasia has barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, two varieties of wheat, and three protein-rich pulses for food; flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. In 2022, France produced 75% of t ...

for textiles; and goats, sheep, and cattle. Eurasian grains were richer in protein, easier to sow, and easier to store than American maize or tropical bananas.

As early Western Asian civilizations developed trading relationships, they found additional useful animals in adjacent territories, such as horses and donkey

The donkey or ass is a domesticated equine. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a separate species, ''Equus asinus''. It was domes ...

s for use in transport. Diamond identifies 13 species of large animals over domesticated in Eurasia, compared with just one in South America (counting the llama

The llama (; or ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with ...

and alpaca

The alpaca (''Lama pacos'') is a species of South American camelid mammal. Traditionally, alpacas were kept in herds that grazed on the level heights of the Andes of Southern Peru, Western Bolivia, Ecuador, and Northern Chile. More recentl ...

as breeds within the same species) and none at all in the rest of the world. Australia and North America suffered from a lack of useful animals due to extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

, probably by human hunting, shortly after the end of the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, and the only domesticated animals

This page gives a list of domesticated animals, also including a list of domestication of animals, animals which are or may be currently undergoing the process of domestication and animals that have an extensive relationship with humans beyond simp ...

in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

came from the East Asian mainland during the Austronesian settlement around 4,000–5,000 years ago. Biological relatives of the horse, including zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), the plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. ...

s and onager

The onager (, ) (''Equus hemionus''), also known as hemione or Asiatic wild ass, is a species of the family Equidae native to Asia. A member of the subgenus ''Asinus'', the onager was Scientific description, described and given its binomial name ...

s, proved untameable; and although African elephant

African elephants are members of the genus ''Loxodonta'' comprising two living elephant species, the African bush elephant (''L. africana'') and the smaller African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''). Both are social herbivores with grey skin. ...

s can be tamed, it is very difficult to breed them in captivity. Diamond describes the small number of domesticated species (14 out of 148 "candidates") as an instance of the Anna Karenina principle: many promising species have just one of several significant difficulties that prevent domestication. He argues that all large mammals that could be domesticated, have been.

Eurasians domesticated goats and sheep for hides, clothing, and cheese; cows for milk; bullocks for tillage

Tillage is the agriculture, agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical wikt:agitation#Noun, agitation of various types, such as digging, stirring, and overturning. Examples of manual labour, human-powered tilling methods using hand tools inc ...

of fields and transport; and benign animals such as pigs and chickens. Large domestic animals such as horses and camels offered the considerable military and economic advantages of mobile transport.

Eurasia's large landmass and long east–west distance increased these advantages. Its large area provided more plant and animal species suitable for domestication. Equally important, its east–west orientation has allowed groups of people to wander and empires to conquer from one end of the continent to the other while staying at the same latitude. This was important because similar climate and cycle of seasons let them keep the same "food production system" – they could keep growing the same crops and raising the same animals all the way from Scotland to Siberia. Doing this throughout history, they spread innovations, languages and diseases everywhere.

By contrast, the north–south orientation of the Americas and Africa created countless difficulties adapting crops domesticated at one

Eurasia's large landmass and long east–west distance increased these advantages. Its large area provided more plant and animal species suitable for domestication. Equally important, its east–west orientation has allowed groups of people to wander and empires to conquer from one end of the continent to the other while staying at the same latitude. This was important because similar climate and cycle of seasons let them keep the same "food production system" – they could keep growing the same crops and raising the same animals all the way from Scotland to Siberia. Doing this throughout history, they spread innovations, languages and diseases everywhere.

By contrast, the north–south orientation of the Americas and Africa created countless difficulties adapting crops domesticated at one latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

for use at other latitudes (and, in North America, adapting crops from one side of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

to the other). Similarly, Africa was fragmented by its extreme variations in climate from north to south: crops and animals that flourished in one area never reached other areas where they could have flourished, because they could not survive the intervening environment. Europe was the ultimate beneficiary of Eurasia's east–west orientation: in the first millennium BCE, the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

areas of Europe adopted Southwestern Asia's animals, plants, and agricultural techniques; in the first millennium

File:1st millennium montage.png, From top left, clockwise: Depiction of Jesus, the central figure in Christianity; The Colosseum, a landmark of the once-mighty Roman Empire; Kaaba, the Great Mosque of Mecca, the holiest site of Islam; Chess, a ne ...

CE, the rest of Europe followed suit.

The plentiful supply of food and the dense populations that it supported made division of labor

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (Departmentalization, specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialis ...

possible. The rise of non-farming specialists such as craftsmen and scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of Printing press, automatic printing.

The work of scribes can involve copying manuscripts and other texts as well as ...

s accelerated economic growth and technological progress. These economic and technological advantages eventually enabled Europeans to conquer the peoples of the other continents in recent centuries by using guns and steel, particularly after the devastation of native populations by the epidemic diseases from germs.

Eurasia's dense populations, high levels of trade, and living in close proximity to livestock resulted in widespread transmission of diseases, including from animals to humans. Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, and influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

were the result of close proximity between dense populations of animals and humans. Natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

endowed most Eurasians with genetic variations making them less susceptible to some diseases, and constant circulation of diseases meant adult individuals had developed immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

to a wide range of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s. When Europeans made contact with the Americas, European diseases (to which Americans had no immunity) ravaged the indigenous American population, rather than the other way around. The "trade" in diseases was a little more balanced in Africa and southern Asia, where endemic malaria and yellow fever made these regions notorious as the "white man's grave". Some researchers say syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

was known to Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

, and others think it was brought from the Americas by Columbus and his successors. The European diseases from germs obliterated indigenous populations so that relatively small numbers of Europeans could maintain dominance.

Diamond proposes geographical explanations for why western European societies, rather than other Eurasian powers such as China, have been the dominant colonizers. He said Europe's geography favored balkanization

Balkanization or Balkanisation is the process involving the fragmentation of an area, country, or region into multiple smaller and hostile units. It is usually caused by differences in ethnicity, culture, religion, and geopolitical interests.

...

into smaller, closer nation-states, bordered by natural barriers of mountains, rivers, and coastline. Advanced civilization developed first in areas whose geography lacked these barriers, such as China, India and Mesopotamia. There, the ease of conquest meant they were dominated by large empires in which manufacturing, trade and knowledge flourished for millennia, while balkanized Europe remained more primitive.

However, at a later stage of development, western Europe's fragmented governmental structure actually became an advantage. Monolithic, isolated empires without serious competition could continue mistaken policies – such as China squandering its naval mastery by banning the building of ocean-going ships – for long periods without immediate consequences. In Western Europe, by contrast, competition from immediate neighbors meant that governments could not afford to suppress economic and technological progress for long; if they did not correct their mistakes, they were out-competed and/or conquered relatively quickly. While the leading powers alternated, a constant was rapid development of knowledge which could not be suppressed. For instance, the Chinese Emperor could ban shipbuilding and be obeyed, ending China's Age of Discovery, but the Pope could not keep Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's ''Dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

'' from being republished in Protestant countries, or Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

and Newton from continuing his progress; this ultimately enabled European merchant ships and navies to navigate around the globe. Western Europe also benefited from a more temperate climate than Southwestern Asia where intense agriculture ultimately damaged the environment, encouraged desertification

Desertification is a type of gradual land degradation of Soil fertility, fertile land into arid desert due to a combination of natural processes and human activities.

The immediate cause of desertification is the loss of most vegetation. This i ...

, and hurt soil fertility

Soil fertility refers to the ability of soil to sustain agricultural plant growth, i.e. to provide plant habitat and result in sustained and consistent yields of high quality.

.

Agriculture

''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' argues thatcities

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

require an ample supply of food, and thus are dependent on agriculture. As farmers do the work of providing food, division of labor allows others freedom to pursue other functions, such as mining and literacy.

The crucial trap for the development of agriculture is the availability of wild edible plant species suitable for domestication. Farming arose early in the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

since the area had an abundance of wild wheat and pulse species that were nutritious and easy to domesticate. In contrast, American farmers had to struggle to develop corn as a useful food from its probable wild ancestor, teosinte

''Zea'' is a genus of flowering plants in the Poaceae, grass family. The best-known species is ''Z. mays'' (variously called maize, corn, or Indian corn), one of the most important crops for human societies throughout much of the world. The four ...

.

Also important to the transition from hunter-gatherer to city-dwelling agrarian societies was the presence of "large" domesticable animals, raised for meat, work, and long-distance communication. Diamond identifies a mere 14 domesticated large mammal species worldwide. The five most useful (cow, horse, sheep, goat, and pig) are all descendants of species endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

. Of the remaining nine, only two (the llama

The llama (; or ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with ...

and alpaca

The alpaca (''Lama pacos'') is a species of South American camelid mammal. Traditionally, alpacas were kept in herds that grazed on the level heights of the Andes of Southern Peru, Western Bolivia, Ecuador, and Northern Chile. More recentl ...

both of South America) are indigenous to a land outside the temperate region of Eurasia.

Due to the Anna Karenina principle, surprisingly few animals are suitable for domestication. Diamond identifies six criteria including the animal being sufficiently docile, gregarious, willing to breed in captivity and having a social dominance hierarchy. Therefore, none of the many African mammals such as the zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), the plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. ...

, antelope

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do ...

, cape buffalo, and African elephant

African elephants are members of the genus ''Loxodonta'' comprising two living elephant species, the African bush elephant (''L. africana'') and the smaller African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''). Both are social herbivores with grey skin. ...

were ever domesticated (although some can be tamed, they are not easily bred in captivity). The Holocene extinction event eliminated many of the megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

that, had they survived, might have become candidate species, and Diamond argues that the pattern of extinction is more severe on continents where animals that had no prior experience of humans were exposed to humans who already possessed advanced hunting techniques (such as the Americas and Australia).

Smaller domesticable animals such as dogs, cats, chickens, and guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy ( ), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'', family Caviidae. Animal fancy, Breeders tend to use the name "cavy" for the ani ...

s may be valuable in various ways to an agricultural society, but will not be adequate in themselves to sustain a large-scale agrarian society. An important example is the use of larger animals such as cattle and horses in plowing land, allowing for much greater crop productivity and the ability to farm a much wider variety of land and soil types than would be possible solely by human muscle power. Large domestic animals also have an important role in the transportation of goods and people over long distances, giving the societies that possess them considerable military and economic advantages.

Geography

Diamond argues that geography shapedhuman migration

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another, with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another ( ...

, not simply by making travel difficult (particularly by latitude), but by how climates affect where domesticable animals can easily travel and where crops can ideally grow easily due to the sun. The dominant Out of Africa theory holds that modern humans developed east of the Great Rift Valley of the African continent at one time or another. The Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

kept people from migrating north to the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

, until later when the Nile River

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

valley became accommodating. Diamond continues to describe the story of human development up to the modern era, through the rapid development of technology, and its dire consequences on hunter-gathering cultures around the world.

Diamond touches on why the dominant powers of the last 500 years have been West European rather than East Asian, especially Chinese. The Asian areas in which big civilizations arose had geographical features conducive to the formation of large, stable, isolated empires which faced no external pressure to change which led to stagnation. Europe's many natural barriers allowed the development of competing nation states. Such competition forced the European nations to encourage innovation and avoid technological stagnation.

Germs

In the later context of theEuropean colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse explored and colonized areas of Europe a ...

, 95% of the indigenous populations are believed to have been killed off by diseases brought by the Europeans. Many were killed by infectious diseases such as smallpox and measles. Similar circumstances were observed in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. Aboriginal Australians and the Khoikhoi population were devastated by smallpox, measles, influenza, and other diseases.

Diamond questions how diseases native to the American continents did not kill off Europeans, and posits that most of these diseases were developed and sustained only in large dense populations in villages and cities. He also states most epidemic diseases evolve from similar diseases of domestic animals. The combined effect of the increased population densities supported by agriculture, and of close human proximity to domesticated animals leading to animal diseases infecting humans, resulted in European societies acquiring a much richer collection of dangerous pathogens to which European people had acquired immunity through natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

(such as the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

and other epidemics) during a longer time than was the case for Native American hunter-gatherers

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially w ...

and farmers.

He mentions the tropical diseases (mainly malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

) that limited European penetration into Africa as an exception. Endemic infectious diseases were also barriers to European colonisation of Southeast Asia and New Guinea.

Success and failure

''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' focuses on why some populations succeeded. Diamond's later book, '' Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed'', focuses on environmental and other factors that have caused some populations to fail.Intellectual background

In the 1930s, theAnnales School

The ''Annales'' school () is a group of historians associated with a style of historiography developed by French historians in the 20th century to stress long-term social history. It is named after its scholarly journal '' Annales. Histoire, S ...

in France undertook the study of long-term historical structures by using a synthesis of geography, history, and sociology. Scholars examined the impact of geography, climate, and land use. Although geography had been nearly eliminated as an academic discipline in the United States after the 1960s, several geography-based historical theories were published in the 1990s.

In 1991, Jared Diamond already considered the question of "why is it that the Eurasians came to dominate other cultures?" in '' The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal'' (part four).

Reception

Praise

Many noted that the large scope of the work makes some oversimplification inevitable while still praising the book as a very erudite and generally effective synthesis of multiple different subjects. Paul R. Ehrlich and E. O. Wilson both praised the book.Northwestern University

Northwestern University (NU) is a Private university, private research university in Evanston, Illinois, United States. Established in 1851 to serve the historic Northwest Territory, it is the oldest University charter, chartered university in ...

economic historian Joel Mokyr interpreted Diamond as a geographical determinist but added that the thinker could never be described as "crude" like many determinists. For Mokyr, Diamond's view that Eurasia succeeded largely because of a uniquely large stock of domesticable plants is flawed because of the possibility of crop manipulation and selection in the plants of other regions: the drawbacks of an indigenous North American plant such as sumpweed could have been bred out, Mokyr wrote, since "all domesticated plants had originally undesirable characteristics" eliminated via "deliberate and lucky selection mechanisms". Mokyr dismissed as unpersuasive Diamond's theory that breeding specimens failing to fix characteristics controlled by multiple genes "lay at the heart of the geographically challenged societies". Mokyr also states that in seeing economic history as centered on successful manipulation of environments, Diamond downplays the role of "the option to move to a more generous and flexible area", and speculated that non-generous environments were the source of much human ingenuity and technology. However, Mokyr still argued that ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' is "one of the more important contributions to long-term economic history and is simply mandatory to anyone who purports to engage Big Questions in the area of long-term global history". He lauded the book as full of "clever arguments about writing, language, path dependence and so on. It is brimming with wisdom and knowledge, and it is the kind of knowledge economic historians have always loved and admired."

Berkeley economic historian Brad DeLong described the book as a "work of complete and total genius". Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

International Relations (IR) scholar Stephen Walt

Stephen Martin Walt (born July 2, 1955) is an American political scientist serving as the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of international relations at the Harvard Kennedy School. A member of the realist school of international relations, Walt ...

in a ''Foreign Policy

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

'' article called the book "an exhilarating read" and put it on a list of the ten books every IR student should read. Tufts University IR scholar Daniel W. Drezner listed the book on his top ten list of must-read books about international economic history.

International Relations scholars Iver B. Neumann (of the London School of Economics and Political Science) and Einar Wigen (of University of Oslo) use ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' as a foil for their own inter-disciplinary work. They write that "while empirical details should, of course, be correct, the primary yardstick for this kind of work cannot be attention to detail." According to the two writers, "Diamond stated clearly that any problematique of this magnitude had to be radically multi-causal and then set to work on one complex of factors, namely ecological ones", and note that Diamond "immediately came in for heavy criticism from specialists working in the disparate fields on which he drew". But Neumann and Wigen also stated, "Until somebody can come up with a better way of interpreting and adding to Diamond's material with a view to understanding the same overarching problematique, his is the best treatment available of the ecological preconditions for why one part of the world, and not another, came to dominate." Historian Tonio Andrade writes that Diamond's book "may not satisfy professional historians on all counts" but that it "does make a bold and compelling case for the different developments that occurred in the Old World versus the New (he is less convincing in his attempts to separate Africa from Eurasia)."

Historian Tom Tomlinson wrote that the magnitude of the task makes it inevitable that Professor Diamond would " severy broad brush-strokes to fill in his argument", but ultimately commended the book. Taking the account of prehistory "on trust" because it was not his area of expertise, Tomlinson stated that the existence of stronger weapons, diseases, and means of transport is convincing as an "immediate cause" of Old World societies and technologies being dominant, but questioned Diamond's view that the way this has transpired has been through certain environments causing greater inventiveness which then caused more sophisticated technology. Tomlinson noted that technology spreads and allows for military conquests and the spread of economic changes, but that in Diamond's book this aspect of human history "is dismissed as largely a question of historical accident". Writing that Diamond gives meager coverage to the history of political thought, the historian suggested that capitalism (which Diamond classes as one of 10 plausible but incomplete explanations) has perhaps played a bigger role in prosperity than Diamond argues.

Tomlinson speculated that Diamond underemphasizes cultural idiosyncrasies as an explanation, and argues (with regards to the "germs" part of Diamond's triad of reasons) that the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

of the 14th century, as well as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

in 19th century Africa, rival the Eurasian devastation of indigenous populations as overall "events of human diffusion and coalescence". Tomlinson also found contentious Diamond's view that humanity's future can one day be foreseen with scientific rigor since this would involve a search for general laws that new theoretical approaches deny the possibility of establishing: "The history of humans cannot properly be equated with the history of dinosaurs, glaciers or nebulas, because these natural phenomena do not consciously create the evidence on which we try to understand them". Tomlinson still described these flaws as "minor", however, and wrote that ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' "remains a very impressive achievement of imagination and exposition".

Another historian, professor J. R. McNeill, complimented the book for "its improbable success in making students of international relations believe that prehistory is worth their attention", but likewise thought Diamond oversold geography as an explanation for history and under-emphasized cultural autonomy. McNeill wrote that the book's success "is well-deserved for the first nineteen chapters–excepting a few passages–but that the twentieth chapter carries the argument beyond the breaking point, and excepting a few paragraphs, is not an intellectual success." But McNeill concluded, "While I have sung its praises only in passing and dwelt on its faults, ..overall I admire the book for its scope, for its clarity, for its erudition across several disciplines, for the stimulus it provides, for its improbable success in making students of international relations believe that prehistory is worth their attention, and, not least, for its compelling illustration that human history is embedded in the larger web of life on earth." Tonio Andrade described McNeill's review as "perhaps the fairest and most succinct summary of professional world historians' perspectives on ''Guns, Germs, and Steel''".

In 2010, Tim Radford of ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' called the book "exhilarating" and lauded the passages about plants and animals as "beautifully constructed".

A 2023 study in the ''Quarterly Journal of Economics'' assessed Diamond's claims about topography influencing Chinese unification and contributing to European fragmentation. The study's model found that topography was a sufficient condition

In logic and mathematics, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between two statements. For example, in the conditional statement: "If then ", is necessary for , because the truth of ...

for the varied outcomes in Asia and Europe, but that it was not a necessary condition.

Criticism

Theanthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

Jason Antrosio described ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' as a form of "academic porn", writing, "Diamond's account makes all the factors of European domination a product of a distant and accidental history" and "has almost no role for human agency—the ability people have to make decisions and influence outcomes. Europeans become inadvertent, accidental conquerors. Natives succumb passively to their fate." He added, "Jared Diamond has done a huge disservice to the telling of human history. He has tremendously distorted the role of domestication and agriculture in that history. Unfortunately his story-telling abilities are so compelling that he has seduced a generation of college-educated readers."

In his last book, published in 2000, the anthropologist and geographer James Morris Blaut criticized ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'', among other reasons, for reviving the theory of environmental determinism, and described Diamond as an example of a modern Eurocentric historian. Blaut criticizes Diamond's loose use of the terms "Eurasia" and "innovative", which he believes misleads the reader into presuming that Western Europe is responsible for technological inventions that arose in the Middle East and Asia.full textAnthropologist Kerim Friedman wrote, "While it is interesting and important to ask why technologies developed in some countries as opposed to others, I think it overlooks a fundamental issue: the inequality within countries as well as between them." Timothy Burke, an instructor in African history at

Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College ( , ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1864, with its first classes held in 1869, Swarthmore is one of the e ...

wrote: "Anthropologists and historians interested in non-Western societies and Western colonialism also get a bit uneasy with a big-picture explanation of world history that seems to cancel out or radically de-emphasize the importance of the many small differences and choices after 1500 whose effects many of us study carefully."

Economists Daron Acemoğlu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson have written extensively about the effect of political institutions on the economic well-being of former European colonies. Their writing finds evidence that, when controlling for the effect of institutions, the income disparity between nations located at various distances from the equator disappears through the use of a two-stage least squares regression quasi-experiment using settler mortality as an instrumental variable. Their 2001 academic paper explicitly mentions and challenges the work of Diamond, and this critique is brought up again in Acemoğlu and Robinson's 2012 book '' Why Nations Fail''.

The book '' Questioning Collapse'' (Cambridge University Press, 2010) is a collection of essays by fifteen archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, and historians criticizing various aspects of Diamond's books '' Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed'' and ''Guns, Germs and Steel''. The book was a result of 2006 meeting of the American Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an American organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropo ...

in response to the misinformation they felt Diamond's popular science publications were causing and the association decided to combine experts from multiple fields of research to cover the claims made in Diamond's and debunk them. The book includes research from indigenous peoples of the societies Diamond discussed as collapsed and also vignettes of living examples of those communities, in order to showcase the main theme of the book on how societies are resilient and change into new forms over time, rather than collapsing.

Awards and honors

''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' won the 1997Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science The Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science is given annually by Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa a ...

. In 1998, it won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction

The Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are awarded annually for the "Letters, Drama, and Music" category. The award is given to a nonfiction book written by an American author and published du ...

, in recognition of its powerful synthesis of many disciplines, and the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Rhône-Poulenc Prize for Science Books.

Publication

''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' was first published by W. W. Norton in March 1997. It was published in Great Britain with the title ''Guns, Germs, and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years'' by Vintage in 1998. It was a selection of Book of the Month Club, History Book Club, Quality Paperback Book Club, and Newbridge Book Club. In 2003 and 2007, updated English-language editions were released without changing any conclusions.. Retrieved September 21, 2015. The

National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

produced a documentary, starring Jared Diamond, based on the book and of the same title, that was broadcast on PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

in July 2005.

See also

* Bantu expansion *James Burke (science historian)

James Burke (born 22 December 1936) is a broadcaster, science historian, author, and television producer. He was one of the main presenters of the BBC1 science series '' Tomorrow's World'' from 1965 to 1971 and created and presented the telev ...

* Alfred W. Crosby

Alfred Worcester Crosby Jr. (January 15, 1931 – March 14, 2018) was a professor of History, Geography, and American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and University of Helsinki. He was the author of books including '' The Columbian ...

* Yuval Noah Harari

Yuval Noah Harari ( ; born 1976) is an Israeli medievalist, military historian, public intellectual, and popular science writer. He currently serves as professor in the Department of History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His first bestse ...

* Marvin Harris

* Population history of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Population figures for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas before European European colonization of the Americas, colonization have been difficult to establish. Estimates have varied widely from as low as 8 million to as many as 100 million, ...

* Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

* '' States and Power in Africa''

*'' Plough, Sword and Book''

*'' Why the West Rules—For Now''

General

*Cultural ecology

Cultural ecology is the study of human adaptations to social and physical environments. Human adaptation refers to both biological and cultural processes that enable a population to survive and reproduce within a given or changing environment. Th ...

* Cultural materialism

* Historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

Books and television

* ''Connections'' (British TV series) * '' The Dawn of Everything'' * '' Deep Time History'' * '' The Fates of Nations'' * '' How Europe Underdeveloped Africa'' (1972) by Pan-African socialist and historianWalter Rodney

Walter Anthony Rodney (23 March 1942 – 13 June 1980) was a Guyanese historian, political activist and academic. His notable works include '' How Europe Underdeveloped Africa'', first published in 1972. He was assassinated in Georgetown, ...

* ''Ishmael'' (Quinn novel)

* ''Origins of the State and Civilization'' (1975) by Elman Service

Elman Rogers Service (May 18, 1915 – November 14, 1996) was an American cultural anthropologist.

Biography

He was born on May 18, 1915, in Tecumseh, Michigan and died on November 14, 1996, in Santa Barbara, California. He earned a bachelor' ...

* '' The Outline of History''

* '' The Rise of the West''

* '' Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind''

* '' The Wealth and Poverty of Nations'' (1995) by David Landes

* '' Wealth, Poverty and Politics''

* '' Why Nations Fail''

References

Further reading

* William McNeill (1976), '' Plagues and Peoples'', New York: Anchor/Doubleday ().External links

*PBS

nbsp;– ''Guns, Germs, and Steel''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Guns, Germs, And Steel 1997 non-fiction books 20th-century history books Books about cultural geography Environmental non-fiction books Eurasian history European colonization of the Americas History books about agriculture History books about civilization Non-fiction books about Indigenous peoples of the Americas Non-fiction books adapted into films Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction–winning works W. W. Norton & Company books Works about the theory of history Works by Jared Diamond World history