The First Hundred Years' War (; 1159–1259) was a series of conflicts and disputes during the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

in which the

House of Capet

The House of Capet () ruled the Kingdom of France from 987 to 1328. It was the most senior line of the Capetian dynasty – itself a derivative dynasty from the Robertians and the Karlings.

The direct line of the House of Capet came to an ...

, rulers of the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

, fought the

House of Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet (Help:IPA/English, /plænˈtædʒənət/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''plan-TAJ-ə-nət'') was a royal house which originated from the Medieval France, French county of Anjou. The name Plantagenet is used by mo ...

(also known as the

House of Anjou

Angevin or House of Anjou may refer to:

*County of Anjou or Duchy of Anjou, a historical county, and later Duchy, in France

**Angevin (language), the traditional langue d'oïl spoken in Anjou

**Counts and Dukes of Anjou

*House of Ingelger, a Franki ...

or the

Angevins), rulers of the

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

. The conflict emerged over the

fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

s in France held by the Angevins, which at their peak covered around half of the territory of the French realm. The struggle between the two dynasties resulted in the gradual conquest of these fiefs by the Capetians and their annexation to the

French crown lands, as well as subsequent attempts by the House of Plantagenet to retake what they believed to be their rightful ancestral claims in western France.

The First Hundred Years' War is retroactively named after the

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

from 1337 to 1453 as it is seen as a precursor to the later conflict, involving many of the same belligerents and dynasties. Like the "second" Hundred Years' War, this conflict was not a single war, but rather a

historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

periodisation

In historiography, periodization is the process or study of categorizing the past into discrete, quantified, and named blocks of time for the purpose of study or analysis.Adam Rabinowitz.It's about time: historical periodization and Linked Ancie ...

to encompass dynastically related conflicts revolving around the dispute over the

Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

.

Overview

Origins

During the conflict, the continental possessions of the

Kings of England

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the heptarchy, seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself king of the ...

were considered to be more important than their insular ones, covering an area significantly greater than the territories controlled by the

Kings of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

who, however, were the

overlords of the former in regards to the continental lands. Indeed, while the Capetian's nominal

suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

extended far beyond the small domain of

Île-de-France

The Île-de-France (; ; ) is the most populous of the eighteen regions of France, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 residents on 1 January 2023. Centered on the capital Paris, it is located in the north-central part of the cou ...

, the actual power they held over many of their vassals, including the Plantagenets, was weak. The Capetian kings sought to expand the authority they had over their own kingdom. These reasons, in combination with the Plantagenet's hold on the sovereign kingdom of England adding to their strength, can be seen as the primary reasons for the conflict.

Time frame

Although the time frame of the conflict is generally accepted to be from the beginning of the "40 years war" in 1159 to the 1259 Treaty of Paris, a few preliminary and residual instances of conflict have occurred between the two dynasties such as the Capetian invasion of Plantagenet-held

Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

in 1152, or during the

Gascon War

The Gascon War, also known as the 1294–1303 Anglo-French War or the Guyenne War (), was a conflict between the kingdoms of France and England. Most of the fighting occurred in the Duchy of Aquitaine, made up of the areas of Guyenne and Gascon ...

starting in 1294, which were both initiated for mostly the same underlying reasons as are seen for the rest of the conflict. They are, however, both relatively minor, and the latter conflict is sufficiently distant in time to be considered separate from the overall conflict. It is also reasonable to extend the start of the conflict to 1154, when the formation of the Angevin Empire can be seen as the true root of the conflict, rather than the dispute over

Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, which merely served as the justification for military action. The Hundred Year's War from 1337 to 1453 is also not accepted as part of the same conflict due to the differing used to initiate the war, and the fact that the two families involved were

cadet branches

A cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets (realm, titles, fiefs, property and inco ...

of the Capetian, and eventually, Plantagenet dynasties (

Valois and

Lancastrian respectively).

The conflict can generally be divided into three distinct phases. The first phase saw the Angevin Empire maintaining dominance over their Capetian rivals. In the second phase, the Angevin Empire experienced a sudden collapse at the hands of the Capetians, culminating in a Capetian invasion of England. The third phase occurred with the Capetian kings now dominant on the continent, while the Plantagenets sought to reclaim the Angevin Empire through various means.

Warfare

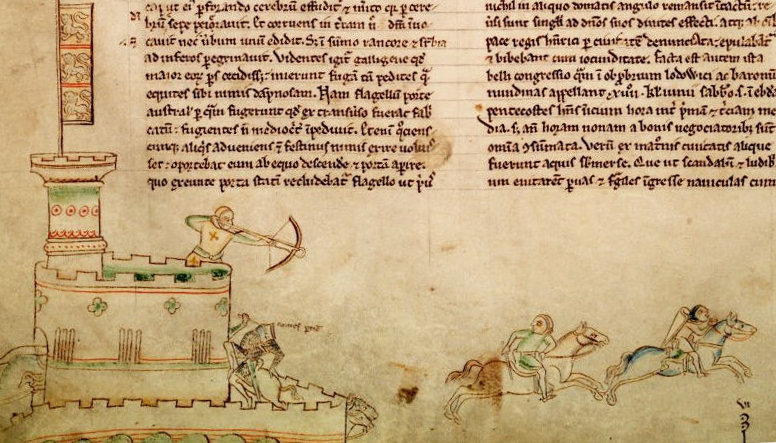

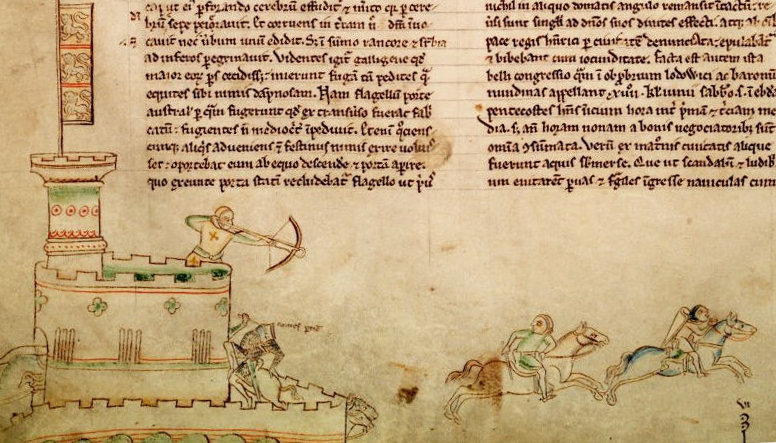

The conflict occurred during a period when the majority of warfare was characterized by

sieges

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characte ...

, siege assaults, siege reliefs, raids, and skirmishes. This was largely due to two factors: the

feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

structure of both kingdoms which hindered the formation of

professional standing armies, and the defensive advantage provided by the widespread presence of

castles

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble. This i ...

. Consequently, warfare was more localized in nature and large

pitched battles

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

were relatively rare due to their typically decisive outcomes. However, this did not lessen the brutality or the death toll. In fact, this style of conflict spread the burden of war across a broader spectrum of society, impacting people of various statuses. While soldiers were often drawn from more distant regions, most combat involved the immediate stakeholders—local nobility and populace alike. As the Plantagenets lost territory on the continent, their ability to wage war became increasingly strained. They had to rely on hired mercenaries for deeper offensive campaigns into France. This is all in contrast to the later "second" Hundred Years' War, during which the

infantry revolution gained momentum, allowing for pitched battles to become more common, and the growing use of

gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

began to undermine the strategic importance of castles.

Significance

The significance of the conflict is often viewed in the context of the later Hundred Years' War, which spanned from 1337 to 1453. Ironically, the intermarriages between the two dynasties—resulting from various peace settlements from the conflict—played a direct role in the Plantagenets' dynastic claim to the French throne, ultimately triggering the more famous Hundred Years' War. The French invasion of England in 1216 also played a significant role in the rise of English nationalism, reinforcing a collective identity that distinguished the English from their French adversaries. The enduring fear of another French invasion in the 14th century further galvanized the lower classes, prompting widespread military preparedness, particularly in the use of the

longbow

A longbow is a type of tall bow that makes a fairly long draw possible. Longbows for hunting and warfare have been made from many different woods in many cultures; in Europe they date from the Paleolithic era and, since the Bronze Age, were mad ...

, as a means of defending the realm.

After the Plantagenet claims to western France ended with the

Treaty of Paris in 1259, the English kings, in regards to their few remaining possessions on the continent, would remain vassals to the French kings and would become more English in nature. The Capetians were also able to consolidate their power, making the kingdom of France the wealthiest and most powerful state in medieval Western Europe.

Angevin ascendancy under Henry II: 1154-1189

Formation of the Angevin Empire

In 1150, amidst a period of civil war in England over the succession of the crown known as

the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Duchy of Normandy, Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adel ...

,

Henry II Plantagenet

Henry II () was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189. During his reign he controlled England, substantial parts of Wales and Ireland, and much of France (including Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine), an area that altogether was la ...

, a claimant to the throne by right of his mother

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

, received the

Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple, King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a r ...

from his father

Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou Geoffrey, Geoffroy, Geoff, etc., may refer to:

People

* Geoffrey (given name), including a list of people with the name Geoffrey or Geoffroy

* Geoffroy (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Geoffroy (musician) (born 1987), Canadi ...

. In response to the looming threat of a united England, Normandy, and Anjou,

Louis VII Capet of France put forward King

Stephen

Stephen or Steven is an English given name, first name. It is particularly significant to Christianity, Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; he is w ...

of England's son,

Eustace

Eustace ( ) is the rendition in English of two phonetically similar Greek given names:

*Εὔσταχυς (''Eústachys'') meaning "fruitful", "fecund"; literally "abundant in grain"; its Latin equivalents are ''Fæcundus/Fecundus''

*Εὐστά ...

, as a pretender to the duchy of Normandy and launched a military campaign to remove Henry from the province. Peace was made in 1151 in which Henry accepted Louis as his feudal lord in response for recognition as the duke of Normandy.

When Geoffrey died in September 1151, Henry inherited the

County of Anjou

The County of Anjou (, ; ; ) was a French county that was the predecessor to the Duchy of Anjou. Its capital was Angers, and its area was roughly co-extensive with the diocese of Angers. Anjou was bordered by Brittany to the west, Maine, France, ...

and

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. On 18 May 1152 he became

Duke of Aquitaine

The duke of Aquitaine (, , ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As successor states of the Visigothic Kingdom ( ...

in right of his wife by marrying

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

in

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

after her first marriage with Louis VII of France was annulled at the Council of Beaugency. As a result of this union, Henry had now possessed a larger proportion of France than Louis. Tensions between the two were revived. Louis organized a coalition against Henry including Stephen of England and Henry's younger brother

Geoffrey Geoffrey, Geoffroy, Geoff, etc., may refer to:

People

* Geoffrey (given name), including a list of people with the name Geoffrey or Geoffroy

* Geoffroy (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Geoffroy (musician) (born 1987), Canadian ...

, among a group of other nobles in France. Fighting broke out along the borders of Normandy, and Louis launched a campaign into Aquitaine. In England, Stephen laid siege to

Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle is a medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Saxon ' ...

which was held by Henry's forces at the time. Henry responded by stabilizing the Norman border, pillaging the

Vexin

Vexin () is a historical county of northern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south betw ...

and then striking south into Anjou against Geoffrey, capturing the castle of

Montsoreau

Montsoreau () is a commune of the Loire Valley in the Maine-et-Loire department in western France on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast and from Paris. The village is listed among '' The Most Beautiful Villages of France'' () and is part of t ...

. Louis soon fell ill and withdrew the campaign, and Geoffrey was forced to come to terms with Henry.

On 6 November 1153, by the

Treaty of Wallingford

The Treaty of Wallingford, also known as the Treaty of Winchester or the Treaty of Westminster, was an agreement reached in England in the summer of 1153. It effectively ended a civil war known as the Anarchy (1135–54), caused by a dispute o ...

(or Treaty of Winchester), he was recognized as the successor of King Stephen of England. When the latter died on 25 October 1154, he ascended the throne of England under the name of Henry II. On Sunday, December 19, he was crowned at

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. This marked the beginning of what is referred to by historians in the modern day as the

Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

. The resources at the disposal of Henry now far exceeded those of the king of France. In 1154 and in 1158, the two kings made a series of agreements to quell the tensions, including the concession of some minor territory to Henry, and the betrothing of Henry's son,

Young Henry

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. In 1170, he became titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Maine. Henry the ...

, to Louis' daughter,

Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

.

Outbreak of the Forty Years' War

In 1156, Henry seized the viscounty of

Thouars

Thouars () is a commune in the Deux-Sèvres department in western France. On 1 January 2019, the former communes Mauzé-Thouarsais, Missé and Sainte-Radegonde were merged into Thouars.

It is on the River Thouet. Its inhabitants are known ...

, thereby controlling communications between the northwest and south-west France. In 1158, he annexed

Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

from the semi-independent duchy of

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

. In 1159, Henry continued to act on his expansionist policy by setting his eyes on the county

Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

which he claimed on Eleanor's behalf. When Henry and Louis discussed the matter of Toulouse, Henry left believing that he had the French king's support for military intervention. Henry invaded Toulouse and laid siege to the city by the same name, only to find Louis visiting

Raymond V, Count of Toulouse

Raymond V (; c. 1134 – c. 1194) was Count of Toulouse from 1148 until his death in 1194.

He was the son of Alphonse I of Toulouse and Faydida of Provence. Alphonse took his son with him on the Second Crusade in 1147. When Alphonse died i ...

in the city. Henry was not prepared to directly attack Louis, who was still his feudal lord, and withdrew, contenting himself with ravaging the surrounding county, seizing various castles and taking the province of

Quercy

Quercy (; , locally ) is a former province of France located in the country's southwest, bounded on the north by Limousin, on the west by Périgord and Agenais, on the south by Gascony and Languedoc, and on the east by Rouergue and Auverg ...

. The episode proved to be a long-running point of dispute between the two kings and the chronicler

William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury (, ''Wilhelmus Neubrigensis'', or ''Willelmus de Novoburgo''. 1136 – 1198), also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon of Anglo-Saxon descent from Bridlington, Eas ...

called the ensuing conflict with Toulouse a "forty years' war."

Despite initial attempts to repair relations, diplomacy broke down. Henry seized the

Vexin

Vexin () is a historical county of northern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south betw ...

and forced a marriage between Young Henry and Margaret.

Theobald V, Count of Blois

Theobald V of Blois (1130 – 20 January 1191), also known as Theobald the Good (), was Count of Blois from 1151 to 1191.

Biography

Theobald was son of Theobald II of Champagne and Matilda of Carinthia. Although he was the second son, Theobald ...

, mobilized his forces on behalf of Louis, however, Henry responded with a surprise attack on

Chaumont, capturing Theobald's castle after a successful siege. Another peace was negotiated in the autumn of 1161, followed by a second peace treaty in 1162 overseen by

Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a Papal election, ...

.

Despite this, Louis consolidated his position by strengthening his alliances and became more vigorous in opposing Henry's increasing power in Europe. Meanwhile, Henry strengthened his grip on the Duchy of Brittany and secured it for his son

Geoffrey Geoffrey, Geoffroy, Geoff, etc., may refer to:

People

* Geoffrey (given name), including a list of people with the name Geoffrey or Geoffroy

* Geoffroy (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Geoffroy (musician) (born 1987), Canadian ...

. Elsewhere, Henry attempted to seize the

Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; or ) is a cultural region in central France.

As of 2016 Auvergne is no longer an administrative division of France. It is generally regarded as conterminous with the land area of the historical Province of Auvergne, which was dis ...

, and continued to apply pressure on Toulouse in a military campaign.

In 1167, the two kings were at war once again. Louis allied himself with the Welsh, Scots, and Bretons, and attacked Normandy. Henry responded by attacking

Chaumont-sur-Epte, where Louis kept his main military arsenal, burning the town to the ground and forcing Louis to abandon his allies and make a private truce. After the short war, Henry continued his campaign against the Bretons, and would later see the capitulation of Toulouse.

Revolt over the Angevin inheritance

Although Henry II wielded much stronger authority within his lands and commanded far greater resources than his Capetian rivals, there was a considerable division in his territories between his sons. Eager to inherit, his three eldest sons

rebelled against him in 1173 with the help of Louis of France. Young Henry and Louis invaded the Vexin intending to reach the Norman capital,

Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

. Henry, who had been in France in order to receive absolution for the

Becket affair, secretly traveled back to England to order an offensive on the rebels, and on his return counter-attacked Louis's army, massacring many of them and pushing the survivors back across the Norman border. In January 1174 the forces of Young Henry and Louis attacked again, threatening to push through into central Normandy. The attack failed and the fighting paused while the winter weather set in. Henry returned to England to face a potential invasion by the Flemish. This ruse allowed

Philip, Count of Flanders

Philip I (1143 – 1 August 1191), commonly known as Philip of Alsace, was count of Flanders from 1168 to 1191. During his rule Flanders prospered economically. He took part in two crusades and died of disease in the Holy Land.

Count of Flanders ...

, and Louis to invade Normandy and reach Rouen, laying siege to the city. However, the defeat and capture of

William of Scotland

William the Lion (), sometimes styled William I (; ) and also known by the nickname ; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Alba from 1165 to 1214. His almost 49- ...

who led another invasion of England in the north allowed Henry to return to Normandy in August. Henry's forces fell upon the French army just before the final French assault on the city began; pushed back into France, Louis requested peace talks, bringing an end to the conflict.

Tension resurfaced between the two kings in the late 1170s over the control of

Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples of berries in the cul ...

. To put additional pressure on Louis, Henry mobilised his armies for war. The papacy intervened and, probably as Henry had planned, the two kings were encouraged to sign a non-aggression treaty in September 1177, under which they promised to undertake a joint crusade. The ownership of the Auvergne and parts of Berry were put to an arbitration panel, which reported in favour of Henry; Henry followed up this success by purchasing

La Marche from the local count. This expansion of Henry's empire once again threatened French security, and promptly put the new peace at risk.

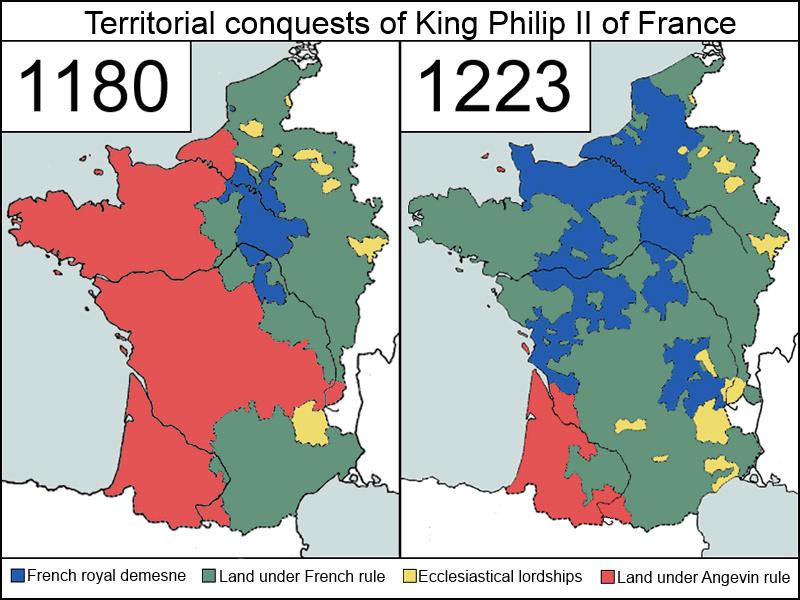

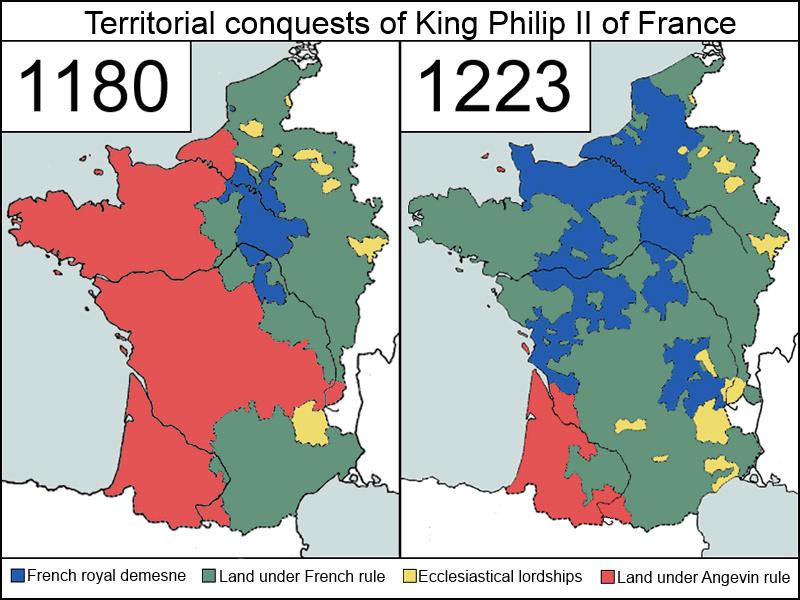

Philip Augustus' first attempts at conquest

In 1180, Louis was succeeded by his son,

Philip II. In 1186, Philip demanded that he be given the Duchy of Brittany and insisted that Henry order his son

Richard the Lionheart

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

to withdraw from Toulouse, where he had been sent with an army to apply new pressure on Count Raymond, Philip Augustus's uncle. Philip Augustus threatened to invade Normandy if this did not happen and reopened the question of the Vexin. Philip Augustus invaded Berry and Henry mobilised a large army which confronted the French at

Châteauroux

Châteauroux ( ; ; ) is the capital city of the French department of Indre, central France and the second-largest town in the province of Berry, after Bourges. Its residents are called ''Castelroussins'' () in French.

Climate

Châteauroux te ...

, before papal intervention brought a truce. During the negotiations, Philip Augustus suggested to Richard that they should ally against Henry, marking the start of a new strategy to divide the father and son.

In 1187, Richard's renewed campaign into Toulouse undermined the truce between Henry and Philip. Both kings mobilized large forces in anticipation of war. In a peace conference held in November 1188, Richard publicly changed sides. It is also in 1188 that the symbolic "

cutting of the elm

The cutting of the elm was a diplomatic altercation between the kings of France and England in 1188, during which an elm tree near Gisors in Normandy was felled.

Diplomatic significance

In the 12th century, the tree marked the traditional place ...

" took place in which Philip ordered the felling of an elm tree on the Norman border, under which both sides traditionally negotiated, signaling his intent to show no mercy to the English. By 1189, the conference broke up with war as Philip and Richard launched a surprise attack on Henry. Henry was caught by surprise at Le Mans but made a forced march north to

Alençon

Alençon (, , ; ) is a commune in Normandy, France, and the capital of the Orne department. It is situated between Paris and Rennes (about west of Paris) and a little over north of Le Mans. Alençon belongs to the intercommunality of Alen� ...

, from where he could escape into the safety of Normandy. Suddenly, Henry turned back south towards Anjou, against the advice of his officials. At Ballan, the two sides negotiated once again, resulting in the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau on 4 July 1189, and the ill-stricken Henry had to recognize his son Richard as his sole heir. Two days later, Henry succumbed to his illness, possibly exacerbated by the betrayal of his son

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

.

Preservation of the Angevin Empire under Richard the Lionheart: 1189-1199

Third Crusade and Philip Augustus' betrayal

In 3 September 1189, Richard the Lionheart was crowned King of England in

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

inheriting his father's vast territories and still commanding much more power than the Capetian monarchy, remaining no less a threat to the Capetians. After the coronation, Richard immediately left for the

Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

alongside King Philip.

Returning early from the crusade in December 1191, Philip Augustus encouraged the rebellion of

John Lackland

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Empi ...

against his brother Richard and profited from the absence of the latter to negotiate a very advantageous treaty for France. Hoping to acquire the English crown with the support of the King of France, John paid homage in 1193. The

Château de Gisors

The Château de Gisors is a castle in the town of Gisors in the Departments of France, department of Eure, France. The castle was a key fortress of the Dukes of Normandy in the 11th and 12th centuries. It was intended to defend the Anglo-Normans, ...

fell to the French in the same year. Then, as Philip Augustus attacked the possessions of the Plantagenets, John gave to the French king eastern Normandy (except Rouen),

Le Vaudreuil

Le Vaudreuil () is a commune in the Eure department in Normandy in northern France.

On 15 April 1969 the commune of Notre-Dame-du-Vaudreuil was joined with that of Saint-Cyr-du-Vaudreuil to form the present Le Vaudreuil.

A bronze statue of th ...

,

Verneuil and Évreux, by written agreement, in January 1194. By his military and diplomatic finesse, Philip kept his rival at bay.

Richard continued the crusade after the departure and seeming betrayal of Philip: he retook the main Palestinian ports up to

Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

, and restored the Latin

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1 ...

although the city itself eluded him. He eventually negotiated a five-year truce with

Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

, likely driven by the urgent matters awaiting him in his own kingdom, and set sail back for England in October 1192. Winter storms overtook him. Forced to stay at

Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, he was captured by Duke

Leopold V of Austria, who put him in the hands of the German Emperor

Henry VI, his enemy. Despite Richard's best efforts during a trial convened by Henry, the emperor continued to detain him, possibly at the request of Philip of France. For the release of Richard, the emperor asked for a ransom of 100,000 marks, plus 50,000 marks to help him conquer Sicily.

[Jean Flori ''Philippe Auguste'', p.68]

Richard's retaliation against Philip

Richard was finally released on 2 February 1194. His mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, paid two-thirds of the ransom, one hundred thousand marks, the balance to be paid later.

Upon his return to England, John was forgiven by his brother and pardoned. Richard's reaction to the Capetian invasion was immediate. Determined to resist Philip's schemes on contested Angevin lands such as the Vexin and Berry, Richard poured all his military expertise and vast resources into the war on the French King. He organised an alliance with his father-in-law, King

Sancho VI of

Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

, who raided Philip's lands from the south. In May 1194, at the head of an English army dispatched from Portsmouth, Richard and

William Marshal

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1146 or 1147 – 14 May 1219), also called William the Marshal (Norman French: ', French: '), was an Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman during High Medieval England who served five English kings: Henry ...

broke Philip's ongoing siege of Verneuil, which was initially promised to Philip by John, and harassed the retreating French army, capturing their siege engines in the process. Philip struck back by sacking the city of Évreux held by John and

Robert of Leicester, the latter of which would soon after be captured by the French while attempting to retake his own castle in

Pacy.

In the

Battle of Fréteval, Richard was able to further push back Philip who barely survived, almost drowning in a river. As a result of this battle, Richard captured a wealth of treasure and numerous written records from Philip, which he secured in the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

and would use against Philip in the wars to come. Richard then moved south to capture Angoulême from an rebellious alliance between

Geoffrey de Rancon Geoffrey III of Rancon was a French army commander who lived in the 12th century. He was Lord of Taillebourg, and served as Eleanor of Aquitaine's army commander during the Second Crusade.

On the day the crusaders were set to cross Mount Cadmus, K ...

and the count

Ademar of Angouleme. In mid-July, while Richard was distracted with this rebellion, Philip won a thorough victory against an Anglo-Norman army led by John and

William d'Aubigny of Arundel who had recently taken Vaudreuil, a key fortress on the Norman border.

It was in August 1194 that Richard decreed for a 'nationalized' system of tournaments to be held in England in order to train the knights of his kingdom to be fiercer in war.

As the campaign season was drawing to an end, the two kings agreed to the Truce of Tillières.

The war resumed in 1195 when Philip besieged Vaudreuil after learning that Henry VI of the Holy Roman Empire was conspiring with Richard to invade France, effectively nullifying the truce. According to English chroniclers, Richard met with Philip, who appeared to be stalling for time with negotiations while his engineers were secretly undermining the walls. When the walls suddenly collapsed, Richard realized Philip's deception and ordered his forces to attack the French. Philip narrowly escaped, and Richard captured what remained of Vaudreuil.

After the events at Vaudreuil, Richard besieged Arques. Philip now pressed his advantage in northeastern Normandy, where he, at the head of 600 knights, conducted a raid at

Dieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

, burning the English ships in the harbor while repulsing an attack by Richard at the same time. Philip now marched southward into the Berry region. His primary objective was the fortress of

Issoudun

Issoudun () is a commune in the Indre department, administrative region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is also referred to as ''Issoundun'', which is the ancient name.

Geography Location

Issoudun is a sub-prefecture, located in the eas ...

, which had just been captured by Richard's mercenary commander and right hand man,

Mercadier

Mercadier or Mercardier (died 10 April 1200) was a famous Occitan warrior of the 12th century, and the leader of a group of mercenaries in the service of King Richard I of England.

In 1183 he appears as a leader of Brabançon mercenaries in So ...

. John also captured

Gamaches

Gamaches () is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Gamaches is situated on the D1015, on the banks of the river Bresle, the border with Seine-Maritime, some southwest of Abbeville.Huge lakes to t ...

located in the Vexin around this time. The French king took the town and was besieging the castle when Richard stormed through French lines and made his way in to reinforce the garrison, while at the same time, another army was approaching Philip's supply lines. Against expectation, Richard laid down his arms and negotiated with Philip, paying homage to him in the process. Philip's situation also became precarious as the arriving Angevin reinforcements meant that Richard's forces began to outnumber his own. As a result, Philip gave up most of his recent conquests in the

Treaty of Louviers The Treaty of Louviers was signed in January 1196 by Philip II of France and Richard I of England between Issoudun and Chârost, when Richard appeared after riding over 150 miles (240 km) in three days. Philip asked permission for his army to ...

in December 1195. During this relatively longer period of peace, Richard began construction on the

Château de Gaillard to fortify Normandy from further invasions which was mostly complete by 1198. The castle was ahead of its time, featuring innovations that would be adopted in castle architecture nearly a century later.

Resumption of war

Political and military conditions seemed promising for Philip at the start of 1196 when Richard's nephew

Arthur I, Duke of Brittany

Arthur I (; ) (29 March 1187 – presumably 1203) was 4th Earl of Richmond and Duke of Brittany between 1196 and 1203. He was the posthumous son of Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, and Constance, Duchess of Brittany. Through Geoffrey, Arthur was ...

ended up in his hands. In July 1196, Philip besieged

Aumâle at the head of a large army, including a contingent led by Count

Baldwin of Flanders. Richard countered the maneuver by capturing

Nonancourt

Nonancourt () is a commune in the Eure department in Normandy in northern France. The writer Louis-François Beffara (1751–1838) and the playwright Lucien Besnard (1872–1955) were born in Nonancourt. Nonancourt station has rail connectio ...

, then marching to Aumâle to relieve the siege. The English attacked the French at their camp around the castle, but were pushed back. Aumâle would surrender a week later. The year continued to go badly for Richard who was wounded in the knee by a crossbow bolt while besieging

Gaillon

Gaillon () is a commune in the Eure department in northern France.

History

The origins of Gaillon are not really known. In 892, Rollo, a Viking chief, might have ravaged Gaillon and the region, before he became the first prince of the Normans ...

, and Nonancourt was recaptured following the battle at Aumâle.

However, Philip's fortunes would not last. The situation slowly turned against Philip over the course of the next three years. In October 1196, Richard negotiated with

Raymond VI

Raymond VI (; 27 October 1156 – 2 August 1222) was Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence from 1194 to 1222. He was also Count of Melgueil (as Raymond IV) from 1173 to 1190.

Early life

Raymond was born at Saint-Gilles, Gard, the son of ...

to bring an end to the ongoing 40-year war between Aquitaine and Toulouse, thus securing Richard's southern border. As part of the settlement, Raymond married Richard's sister,

Joan. Richard also won over Count Baldwin, switching sides in 1197. The same year, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI died and was succeeded by

Otto IV

Otto IV (1175 – 19 May 1218) was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1209 until his death in 1218.

Otto spent most of his early life in England and France. He was a follower of his uncle Richard the Lionheart, who made him Count of Poitou in 1196 ...

, Richard's nephew, who put additional pressure on Philip and threatened an invasion into France. Finally, many Norman lords were switching sides and returning to Richard's camp.

In 1197 Richard invaded the Vexin, taking

Courcelles-sur-Seine

Courcelles-sur-Seine (, literally ''Courcelles on Seine'') is a commune in the Eure department in northern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Eure department

The following is a list of the 585 communes of the Eure department ...

and

Boury-en-Vexin before returning to

Dangu. Philip, believing that Courcelles was still holding out, went to its relief. Discovering what was happening, Richard decided to attack the French king's forces, catching Philip by surprise, resulting in an English victory at the

Battle of Gisors (sometimes called Courcelles). In this battle, Richard reportedly yelled "

Dieu et mon droit

(, ), which means , is the motto of the monarch of the United Kingdom. It appears on a scroll beneath the shield of the version of the coat of arms of the United Kingdom used outside Scotland. The motto is said to have first been used by Ri ...

" in battle, meaning "God and my right" signifying that Richard was no longer willing to pay homage to Philip for his domain in France. Philip's forces withdrew and attempted to reach the fortress of Gisors. Bunched together, the French knights with king Philip attempted to cross the

Epte

The Epte () is a river in Seine-Maritime and Eure, in Normandy, France. It is a right tributary of the Seine, long. The river rises in Seine-Maritime in the Pays de Bray, near Forges-les-Eaux, and empties into the Seine not far from Giverny. O ...

River on a bridge that promptly collapsed under their weight, almost drowning Philip in the process. He was dragged out of the river and shut himself up in Gisors, having successfully evaded Richard and reinforced the fortress.

Philip soon planned a new offensive, launching destructive raids into Normandy and again targeting Évreux. Richard countered Philip's thrust with a counterattack in the Vexin, while Mercadier led a raid on

Abbeville

Abbeville (; ; ) is a commune in the Somme department and in Hauts-de-France region in northern France.

It is the of one of the arrondissements of Somme. Located on the river Somme, it was the capital of Ponthieu.

Geography

Location

A ...

. The problem was compounded by the Flemish invasion of

Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities include Arras (Dutch: ...

. By autumn 1198, Richard had regained almost all that had been lost in 1193. With the warring sides in a deadlock, Philip offered a truce so that discussions could begin towards a more permanent peace, with the offer that he would return all of the territories except for Gisors. The new

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

, who wanted to set up a new crusade, also pushed the two kings to negotiate.

In mid-January 1199, the two kings met for a final meeting, Richard standing on the deck of a boat, and Philip on his horse on the banks of the Seine River. Shouting terms at each other, they could not reach an agreement on the terms of a permanent truce, but they did agree to further mediation, which resulted in a five-year truce that held. The situation ended abruptly. During the siege of the castle of

Châlus

Châlus (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine Regions of France, region in western France.

History

Richard I of England, Richard I, King of England was siege, bes ...

(Limousin) held by a rebel garrison in 1199, Richard was hit by another crossbow bolt in the left shoulder, near his neck. He succumbed to his injuries a few days later, on April 6, forty-one years old and at the height of his glory.

Fall of the Angevin Empire under John Lackland: 1199-1214

Dispute over the Angevin succession

John Lackland succeeded his brother Richard. The succession was not unopposed: facing John was his nephew, 12-year-old

Arthur of Brittany

Arthur I (; ) (29 March 1187 – presumably 1203) was 4th Earl of Richmond and Duke of Brittany between 1196 and 1203. He was the posthumous son of Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, and Constance, Duchess of Brittany. Through Geoffrey, Arthur was t ...

, son of his elder brother

Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany

Geoffrey II (; , ; 23 September 1158 – 19 August 1186) was Duke of Brittany and Earl of Richmond between 1181 and 1186, through his marriage to Constance, Duchess of Brittany. Geoffrey was the fourth of five sons of Henry II of England and El ...

who died in 1186. Philip Augustus supported this rivalry, and while he had taken the position of John against Richard, this time he took the position of Arthur against John. Philip received the

homage of Arthur, as

Duke of Brittany

This is a list of rulers of Brittany. In different epochs the rulers of Brittany were kings, princes, and dukes. The Breton ruler was sometimes elected, sometimes attained the position by conquest or intrigue, or by hereditary right. Hereditary ...

, in spring 1199 for the counties of Anjou, Maine and Touraine. This allowed him to negotiate from a position of strength with John Lackland; thus the

Treaty of Le Goulet

The Treaty of Le Goulet was a treaty signed by King John of England and King Philip II of France in May 1200. It ended the first succession war following Richard I’s death, temporarily settling territorial disputes over Normandy and recogniz ...

was created in 1200 which aimed to settle the claims the Angevin kings of England had on French lands, with the exception of Aquitaine, in order to end the constant dispute over Normandy. The treaty was sealed by the marriage of

Louis of France and

Blanche of Castile, John's niece.

However, the hostilities did not cease. Philip again took the cause of Arthur, and summoned John his vassal under the Treaty of Le Goulet for his actions in Aquitaine and Tours. John, naturally, did not present himself, and the court of France pronounced the confiscation of his fiefs.

In the spring of 1202 Philip attacked Normandy while Arthur attacked

Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

, but the young duke was surprised by King John in the

Battle of Mirebeau

The Battle of Mirebeau was a battle in 1202 between the House of Lusignan-Breton alliance and the Kingdom of England. King John of England successfully smashed the Lusignan army by surprise.

Background

After Richard I's death on 6 April 119 ...

, and taken prisoner with his troops as well as his sister

Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany

Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany ( – 10 August 1241), also known as Damsel of Brittany, Pearl of Brittany, or Beauty of Brittany, was the eldest daughter of Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, and Constance, Duchess of Brittany. Her father was the ...

. Arthur of Brittany disappeared in the following months while in captivity, probably murdered in early 1203. Philip then provided support to vassals of Arthur and resumed his actions in Normandy in spring 1203. Philip ordered Eleanor be released, which John eventually refused. In 1208 when it was believed that Arthur had died, Bretons supported his half-sister Alix to succeed instead of the captive Eleanor, whose claim was supported by John.

Fall of Normandy and Poitou

Around the turn of the 13th century, warfare in Normandy was defined by slow but steady advances due to the high density of castles in the region. In September 1203, Philip dismantled the system of Norman castles around Château Gaillard, notably taking Le Vaudreuil. Once the immediate area around the castle was secured, Philip began the

Siege of Château Gaillard. An army led by John of England and William Marshal fell upon the besieging French army in an attempt to relieve the siege. Though the attack was initially successful, the convoluted battle plan led to the English being unable to achieve their objective. The French counterattack routed the English forces, leading John to retreat and invade Brittany instead in order to bait the French into withdrawing from the siege. Philip, understanding the importance of the castle for securing the rest of Normandy, refused to lift the siege. The defending garrison of the castle led by

Roger De Lacy

Roger de Lacy (died after 1106) was an Anglo-Norman nobleman, a Marcher Lord on the Welsh border. Roger was a castle builder, especially at Ludlow Castle.

Lands and titles

From his father, Walter de Lacy, he inherited Castle Frome, Here ...

continued to stubbornly resist French advances, reportedly going as far as using

Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon system used by the Byzantine Empire from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state secret; historians have variously speculated that it was based on saltp ...

on the enemy, until 6 March 1204 when the attackers finally reached the inner bailey of the castle.

Normandy was now open for the taking. Philip pressed his advantage;

Falaise,

Caen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

,

Bayeux

Bayeux (, ; ) is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy in northwestern France.

Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It is also known as the fir ...

, and

Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

surrendered 24 June 1204, despairing the aid of John Lackland, who did not come.

Arques and

Verneuil fell immediately after, completing the success of Philip, who had conquered Normandy in two years of campaign. Philip then turned to the

Loire Valley

The Loire Valley (, ), spanning , is a valley located in the middle stretch of the Loire river in central France, in both the administrative regions Pays de la Loire and Centre-Val de Loire. The area of the Loire Valley comprises about . It is r ...

, where he took

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

in August 1204, and

Loches

Loches (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

It is situated southeast of Tours by road, on the left bank of the river Indre (river), Indre.

History

Loch ...

and

Chinon

Chinon () is a Communes of France, commune in the Indre-et-Loire Departments of France, department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginn ...

in 1205. The failures of John were not received well by the nobility back in England.

Consolidation of Capetian conquests

John and Philip finally agreed to a truce in

Thouars

Thouars () is a commune in the Deux-Sèvres department in western France. On 1 January 2019, the former communes Mauzé-Thouarsais, Missé and Sainte-Radegonde were merged into Thouars.

It is on the River Thouet. Its inhabitants are known ...

, on 13 October 1206. For

Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

, it was then necessary to stabilize these rapid conquests. Since 1204, Philip published an order imposing the use of Norman, instead of Angevin, currency. Philip Augustus also built the

castle of Rouen, an imposing fortress of Philippian style and the locus of Capetian power in Normandy.

From 1206 to 1212, Philip Augustus strove to strengthen his territorial conquests. Capetian domination was accepted in

Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

,

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, and

Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; or ) is a cultural region in central France.

As of 2016 Auvergne is no longer an administrative division of France. It is generally regarded as conterminous with the land area of the historical Province of Auvergne, which was dis ...

, but the counties of

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

and

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

remain reluctant.

Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne, became a primary concern. Despite the favors of

Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

, who married in 1210 his son

Philip Hurepel

Philip I of Boulogne (Philip Hurepel) (1200–1235) was a French prince, Count of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis in his own right, and Count of Boulogne, Mortain, Aumale, and Dammartin-en-Goële ''jure uxoris''.

Philip was born in September 1200, the s ...

to

Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Mathilda (gastropod), ''Mathilda'' (gastropod), a genus of gastropods in the family Mathildidae

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1 ...

, daughter of Renaud, he continued to negotiate with the enemy camp. The suspicions of Philip took shape when the count began to fortify

Mortain

Mortain () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Mortain-Bocage.

Geography

Mortain is situated on a rocky hill rising above the gorge of the ...

, in western Normandy. In 1211, Philip went on the offensive, taking

Mortain

Mortain () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Mortain-Bocage.

Geography

Mortain is situated on a rocky hill rising above the gorge of the ...

,

Aumale

Aumale (), formerly known as Albemarle," is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France. It lies on the River Bresle.

History

The town's Latin name was ''Alba Marla''. It was raised by William ...

and

Dammartin. Renaud de Dammartin fled to the

county of Bar

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

, and was no longer an immediate threat.

Anti-French coalition

The incredible success of Philip Augustus soon brought all of his rivals to unite against him. The opposition formed in 1212. John allied with his nephew, Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who was currently facing an internal crisis within the Empire in which the French supported Otto's opposition,

Philip of Swabia

Philip of Swabia (February/March 1177 – 21 June 1208), styled Philip II in his charters, was a member of the House of Hohenstaufen and King of Germany from 1198 until his assassination.

The death of Philip's older brother Henry VI, Holy Roman E ...

. Renaud de Dammartin was the real architect of the coalition. He had nothing to lose when he went to

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

to seek the support of Otto and England, where he paid homage to John. Hostilities between Philip and John resumed immediately.

At the same time, the first operations of the

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

, led by French barons, saw the quarrel between

Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse

Raymond VI (; 27 October 1156 – 2 August 1222) was Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence from 1194 to 1222. He was also Count of Melgueil (as Raymond IV) from 1173 to 1190.

Early life

Raymond was born at Saint-Gilles, Gard, the son of ...

and the Crusaders. Philip Augustus refused to intervene and focused on the English danger. He gathered his barons in Soissons on 8 April 1213, ordering his son Louis to lead the expedition against England and won the support of all his vassals, except one,

Ferdinand, Count of Flanders

Ferdinand ( Portuguese: ''Fernando'', French and Dutch: ''Ferrand''; 24 March 1188 – 27 July 1233) reigned as '' jure uxoris'' Count of Flanders and Hainaut from his marriage to Countess Joan, celebrated in Paris in 1212, until his death. B ...

, whom he himself had installed two years earlier. Philip then sought further support, particularly with

Henry I, Duke of Brabant

Henry I (, ; c. 1165 – 5 September 1235), named "The Courageous", was a member of the House of Reginar and first duke of Brabant from 1183/84 until his death.

Early life

Henry was possibly born in Leuven (Louvain), the son of Count Godf ...

. After some hesitation,

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

on the other hand chose to support John, which provided moral support, but no direct military advantage. The preparations of the conflict persisted: the initial project of Philip, who wanted to invade England, was thwarted when his fleet was attacked by the enemy coalition at the

Battle of Damme

The Battle of Damme was fought on 30 and 31 May 1213 during the 1213–1214 Anglo-French War. An English fleet led by William Longespée, Earl of Salisbury accidentally encountered a large French fleet under the command of Savari de Maulé ...

in May 1213. The following month saw Philip and Louis strive against the counties of

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

and

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

. The northern cities were almost all devastated.

1214 campaign of John Lackland in the west

John crossed to Aquitaine with his force at a very unusual season. Sailing from

Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, they landed at

La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

on 15 February 1214. He called the feudal levies of

Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne ( , ; ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the Catholic archdiocese of Bordeaux.

Name

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transform ...

to reinforce him and marched into Poitou, where he was joined by

Hugh IX of Lusignan

Hugh IX "le Brun" of Lusignan (1163/1168 – 5 November 1219) was the grandson of Hugh VIII. His father, also Hugh (b. c. 1141), was the co-seigneur of Lusignan from 1164, marrying a woman named Orengarde before 1162 or about 1167 and dying ...

and by

Hervé, Count of Nevers. Making a great display of his troops, John overran Poitou in March, then crossed the Loire and invaded Anjou, the ancient patrimony of his house. As he expected, the King of France marched to check the invasion, taking with him his son,

Prince Louis, and the pick of the feudal levies of his realm. Moving by

Saumur

Saumur () is a Communes of France, commune in the Maine-et-Loire Departments of France, department in western France.

The town is located between the Loire and Thouet rivers, and is surrounded by the vineyards of Saumur itself, Chinon, Bourgu ...

and

Chinon

Chinon () is a Communes of France, commune in the Indre-et-Loire Departments of France, department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginn ...

, he endeavoured to cut off John's line of retreat towards Aquitaine. However, abandoning Anjou, the English king hastened rapidly southward, and, evading the enemy, reached

Limoges

Limoges ( , , ; , locally ) is a city and Communes of France, commune, and the prefecture of the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in west-central France. It was the administrative capital of the former Limousin region. Situated o ...

on 3 April. By those operations, John had drawn Philip far to the south. Philip, however, refused to pursue John any farther and, after ravaging the revolted districts of Poitou, marched homewards. At

Châteauroux

Châteauroux ( ; ; ) is the capital city of the French department of Indre, central France and the second-largest town in the province of Berry, after Bourges. Its residents are called ''Castelroussins'' () in French.

Climate

Châteauroux te ...

, he handed over a few thousand troops to his son and returned with the rest to the north.

John was still determined to tie down as large a force as possible. When he heard Philip had departed, he at once faced about and re-entered Poitou in May. Rapidly passing the Loire, he again invaded Anjou and, after subduing many towns, laid siege to the strong castle of Roche-au-Moines on 19 June. He had lain in front of it for fifteen days when Prince Louis marched to it with his relief army, reinforced by Angevin levies under

William des Roches

William des Roches (died 1222) (in French Guillaume des Roches) was a French knight and crusader who acted as Seneschal of Anjou, of Maine and of Touraine. After serving the Angevin kings of England, in 1202 he changed his loyalty to King Philip I ...

and

Amaury I de Craon. However, despite his significantly larger army, the English king was not prepared to fight, as he deemed his Poitevin allies, as well as his hired mercenaries, to be untrustworthy. He recrossed the Loire on July 3 and retreated to La Rochelle, with his rearguard suffering immensely at the hands of the French forces in the process. These actions constituted what is referred to as the

Battle of Roche-au-Moines. But the coalition was not yet lost: everything depended on the eastern theatre of the war.

Battle of Bouvines

The final confrontation between the armies of Philip and the coalition led by Otto, was now inevitable, after several weeks of approach and avoidance. Otto's army had a sizeable English contingent on the right-wing led by

William Longespée, the illegitimate son of Henry II and half brother to John. On Sunday 27 July 1214 the army of Philip, pursued by the coalition, arrived at

Bouvines

Bouvines (; ) is a commune and village in the Nord department in northern France. It is on the French- Belgian border between Lille and Tournai.

History

On 27 July 1214, the Battle of Bouvines was fought here between the forces of the French ...

to cross the bridge over the

Marque

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's goods or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create and ...

. At that Sunday, the prohibition to fight was absolute for Christians, but Otto decided to go on with the offensive, hoping to surprise the enemy while crossing the bridge. Philip's army was greatly surprised from the rear, but he quickly reorganized his troops before they could be engaged on the bridge. They quickly turned against the coalition. The French right wing fought against the Flemish knights, led by Ferdinand. At the center where fiercest of the fighting occurred, Philip and Otto fought in person. In the cavalry melee, Philip was unseated, and he fell, but his knights protected him, offered him a fresh horse, and the king resumed the assault until Otto ordered a retreat. Finally, on the left, the supporters of Philip ended the career of Renaud de Dammartin who was leading the knights from Brabant, as well as Longespée, both of whom were captured by the French after a long resistance. Fate had turned in favor of Philip, despite the numerical inferiority of his troops. The victory was decisive: the Emperor fled, Philip's men captured 130 prisoners, including five counts, including the reviled traitor, Renaud of Dammartin, and the Count of Flanders, Ferdinand.

Capetian success

The coalition was dissolved after its defeat. On 18 September 1214, in Chinon, Philip signed a truce for five years. John returned to England in 1214. By the

Treaty of Chinon, John Lackland abandoned all his possessions to the north of the Loire:

Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples of berries in the cul ...

,

Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and Vien ...

,

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and

Anjou

Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

** Du ...

returned to the royal domain, which then covered a third of France, greatly enlarged and free from external threat. John acknowledged

Alix

''Alix'', or ''The Adventures of Alix'', is a Franco-Belgian comics series drawn in the ligne claire style by Jacques Martin. The stories revolve around a young Gallo-Roman man named Alix in the late Roman Republic. Although the series is ren ...

as duchess of Brittany and gave up the claim of Eleanor. The Capetian royal domain and the vast area north of the Loire enjoyed repose under the terms of the truce concluded in Chinon in 1215; originally for five years and then extended in 1220 with the guarantee of Louis, an association which marked the beginning of Philip's transition to his son and heir.

Invasion of England and further conquests in France under Louis the Lion: 1215-1224

Intervention in the First Barons' War

The victory was complete on the continent, but Philip's ambitions did not stop there. Indeed, Philip Augustus wanted to go further against John of England. He thus argued that John should be deprived of the throne, recalling his betrayal of Richard in 1194, and the murder of his nephew Arthur. Arguing a questionable interpretation also of the genealogy of his wife Blanche of Castile, Prince Louis "the Lion" of France, at the request of the English barons in rebellion during the

First Baron's War, led an expedition to attempt the conquest of England. The landing took place in

Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

on May 1216. At the head of numerous troops (1,200 knights, plus many English rebels), Louis conquered much of the English kingdom, including

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, where he settled and proclaimed himself as King of England with the support of the English rebel barons. Only

Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places

*Detroit–Windsor, Michigan-Ontario, USA-Canada, North America; a cross-border metropolitan region

Australia New South Wales

*Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area Queen ...

,

Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the 16th president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln (na ...

and

Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

resisted and were subsequently besieged by Louis' forces. But despite the warm welcome to Louis by a majority of English bishops, the support of the pope to John remained firm, and Louis was excommunicated. The attitude of Philip Augustus towards this expedition was ambiguous; he did not officially support it and even criticized his son's strategy for the conquest of England, but it is unlikely that he had not given his consent to it, at least privately.