Faraday Michael Christmas Lecture Detail on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English

In June 1832, the

In June 1832, the  Faraday had a

Faraday had a  Having provided a number of various service projects for the British government, when asked by the government to advise on the production of chemical weapons for use in the

Having provided a number of various service projects for the British government, when asked by the government to advise on the production of chemical weapons for use in the

Faraday's earliest chemical work was as an assistant to

Faraday's earliest chemical work was as an assistant to

In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist

In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist  From his initial discovery in 1821, Faraday continued his laboratory work, exploring electromagnetic properties of materials and developing requisite experience. In 1824, Faraday briefly set up a circuit to study whether a magnetic field could regulate the flow of a current in an adjacent wire, but he found no such relationship. This experiment followed similar work conducted with light and magnets three years earlier that yielded identical results. During the next seven years, Faraday spent much of his time perfecting his recipe for optical quality (heavy) glass, borosilicate of lead, which he used in his future studies connecting light with magnetism. In his spare time, Faraday continued publishing his experimental work on optics and electromagnetism; he conducted correspondence with scientists whom he had met on his journeys across Europe with Davy, and who were also working on electromagnetism. Two years after the death of Davy, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered

From his initial discovery in 1821, Faraday continued his laboratory work, exploring electromagnetic properties of materials and developing requisite experience. In 1824, Faraday briefly set up a circuit to study whether a magnetic field could regulate the flow of a current in an adjacent wire, but he found no such relationship. This experiment followed similar work conducted with light and magnets three years earlier that yielded identical results. During the next seven years, Faraday spent much of his time perfecting his recipe for optical quality (heavy) glass, borosilicate of lead, which he used in his future studies connecting light with magnetism. In his spare time, Faraday continued publishing his experimental work on optics and electromagnetism; he conducted correspondence with scientists whom he had met on his journeys across Europe with Davy, and who were also working on electromagnetism. Two years after the death of Davy, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered

Faraday's breakthrough came when he wrapped two insulated coils of wire around an iron ring, and found that, upon passing a current through one coil, a momentary current was induced in the other coil. This phenomenon is now known as

Faraday's breakthrough came when he wrapped two insulated coils of wire around an iron ring, and found that, upon passing a current through one coil, a momentary current was induced in the other coil. This phenomenon is now known as  In 1832, he completed a series of experiments aimed at investigating the fundamental nature of electricity; Faraday used " static", batteries, and "

In 1832, he completed a series of experiments aimed at investigating the fundamental nature of electricity; Faraday used " static", batteries, and "

In 1845, Faraday discovered that many materials exhibit a weak repulsion from a magnetic field: an effect he termed

In 1845, Faraday discovered that many materials exhibit a weak repulsion from a magnetic field: an effect he termed

Faraday had a long association with the

Faraday had a long association with the  As a respected scientist in a nation with strong maritime interests, Faraday spent extensive amounts of time on projects such as the construction and operation of

As a respected scientist in a nation with strong maritime interests, Faraday spent extensive amounts of time on projects such as the construction and operation of  Faraday assisted with the planning and judging of exhibits for the

Faraday assisted with the planning and judging of exhibits for the

A

A

File:Michael Faraday (1791-1867).jpg, Portrait of young Michael Faraday,

File:M Faraday Lab H Moore.jpg, Michael Faraday in his laboratory,

File:Royal Institution - Michael Faraday's study.jpg, Michael Faraday's study at the Royal Institution

File:Michael Faradays Flat at Royal Institution.jpg, Michael Faraday's flat at the Royal Institution

File:Harriett Moore small.jpg, Artist Harriet Jane Moore who documented Faraday's life in watercolours

Faraday's books, with the exception of ''Chemical Manipulation'', were collections of scientific papers or transcriptions of lectures.

Faraday's books, with the exception of ''Chemical Manipulation'', were collections of scientific papers or transcriptions of lectures.

2nd ed. 18303rd ed. 1842

* ; vol. iii. Richard Taylor and William Francis, 1855 * * * * – published in eight volumes; see also th

2009 publication

of Faraday's diary * * – vol. 2, 1993; vol. 3, 1996; vol. 4, 1999 *

Course of six lectures on the various forces of matter, and their relations to each other

London; Glasgow: R. Griffin, 1860. * The Liquefaction of Gases, Edinburgh: W.F. Clay, 1896.

The letters of Faraday and Schoenbein 1836–1862. With notes, comments and references to contemporary letters

London: Williams & Norgate 1899.

Digital edition

by the

Biography at The Royal Institution of Great Britain

Faraday as a Discoverer by John Tyndall, Project Gutenberg

(downloads)

The Life and Discoveries of Michael Faraday

by J. A. Crowther, London:

Complete Correspondence of Michael Faraday

Searchable full texts of all letters to and from Faraday, based on the standard edition by Frank James

Video Podcast

with Sir John Cadogan talking about Benzene since Faraday

The letters of Faraday and Schoenbein 1836–1862. With notes, comments and references to contemporary letters (1899)

full downloa

PDF

Faraday School, located on Trinity Buoy Wharf

at the New Model School Company Limited's website * ,

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

and physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who contributed to the study of electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between Electric potential, electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve Electron, electrons moving via an electronic ...

and electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

, diamagnetism

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnet ...

, and electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

. Although Faraday received little formal education, as a self-made man, he was one of the most influential scientists in history. It was by his research on the magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

around a conductor

Conductor or conduction may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Bone conduction, the conduction of sound to the inner ear

* Conduction aphasia, a language disorder

Mathematics

* Conductor (ring theory)

* Conductor of an abelian variety

* Cond ...

carrying a direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional electric current, flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor (material), conductor such as a wire, but can also flow throug ...

that Faraday established the concept of the electromagnetic field

An electromagnetic field (also EM field) is a physical field, varying in space and time, that represents the electric and magnetic influences generated by and acting upon electric charges. The field at any point in space and time can be regarde ...

in physics. Faraday also established that magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

could affect rays of light and that there was an underlying relationship between the two phenomena. the 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. He similarly discovered the principles of electromagnetic induction, diamagnetism, and the laws of electrolysis

Faraday's laws of electrolysis are quantitative relationships based on the electrochemical research published by Michael Faraday in 1833.

First law

Michael Faraday reported that the mass () of a substance deposited or liberated at an electrod ...

. His inventions of electromagnetic rotary devices formed the foundation of electric motor technology, and it was largely due to his efforts that electricity became practical for use in technology. The SI unit of capacitance

Capacitance is the ability of an object to store electric charge. It is measured by the change in charge in response to a difference in electric potential, expressed as the ratio of those quantities. Commonly recognized are two closely related ...

, the farad

The farad (symbol: F) is the unit of electrical capacitance, the ability of a body to store an electrical charge, in the International System of Units, International System of Units (SI), equivalent to 1 coulomb per volt (C/V). It is named afte ...

, is named after him.

As a chemist, Faraday discovered benzene

Benzene is an Organic compound, organic chemical compound with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar hexagonal Ring (chemistry), ring with one hyd ...

, investigated the clathrate hydrate

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, or hydrates, are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped ins ...

of chlorine, invented an early form of the Bunsen burner

A Bunsen burner, named after Robert Bunsen, is a kind of ambient air gas burner used as laboratory equipment; it produces a single open gas flame, and is used for heating, sterilization, and combustion.

The gas can be natural gas (which is main ...

and the system of oxidation number

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to other atoms are fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. Concep ...

s, and popularised terminology such as "anode

An anode usually is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, which is usually an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the devic ...

", "cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device such as a lead-acid battery. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. Conventional curren ...

", "electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or a gas). In electrochemical cells, electrodes are essential parts that can consist of a varie ...

" and "ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

". Faraday ultimately became the first and foremost Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, a lifetime position.

Faraday was an experimentalist who conveyed his ideas in clear and simple language. His mathematical abilities did not extend as far as trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

and were limited to the simplest algebra. Physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

took the work of Faraday and others and summarised it in a set of equations which is accepted as the basis of all modern theories of electromagnetic phenomena. On Faraday's uses of lines of force

In the history of physics, a line of force in Michael Faraday's extended sense is synonymous with James Clerk Maxwell's line of induction. According to J.J. Thomson, Faraday usually discusses ''lines of force'' as chains of polarized particles in ...

, Maxwell wrote that they show Faraday "to have been in reality a mathematician of a very high order – one from whom the mathematicians of the future may derive valuable and fertile methods."

A highly principled scientist, Faraday devoted considerable time and energy to public service. He worked on optimising lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lens (optics), lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Ligh ...

s and protecting ships from corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

. With Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, he produced a forensic investigation

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

on a colliery

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extra ...

explosion at Haswell, County Durham, indicating for the first time that coal dust

Coal dust is a fine-powdered form of coal which is created by the crushing, grinding, or pulverizer, pulverization of coal rock. Because of the brittle nature of coal, coal dust can be created by mining, transporting, or mechanically handling it. ...

contributed to the severity of the explosion, and demonstrating how ventilation could have prevented it. Faraday also investigated industrial pollution at Swansea

Swansea ( ; ) is a coastal City status in the United Kingdom, city and the List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, second-largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of ...

, air pollution

Air pollution is the presence of substances in the Atmosphere of Earth, air that are harmful to humans, other living beings or the environment. Pollutants can be Gas, gases like Ground-level ozone, ozone or nitrogen oxides or small particles li ...

at the Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's official maker of British coins. It is currently located in Llantrisant, Wales, where it moved in 1968.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly ow ...

, and wrote to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' on the foul condition of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

during The Great Stink

The Great Stink was an event in Central London during July and August 1858 in which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been ...

. He refused to work on developing chemical weapons for use in the Crimean War, citing ethical reservations. He declined to have his lectures published, preferring people to recreate the experiments for themselves, to better experience the discovery, and told a publisher: "I have always loved science more than money & because my occupation is almost entirely personal I cannot afford to get rich."

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

kept a portrait of Faraday on his study wall, alongside those of Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

and James Clerk Maxwell. Physicist Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

stated, "When we consider the magnitude and extent of his discoveries and their influence on the progress of science and of industry, there is no honour too great to pay to the memory of Faraday, one of the greatest scientific discoverers of all time." Rao, C.N.R. (2000). ''Understanding Chemistry''. Universities Press. . p. 281.

Biography

Early life

Michael Faraday was born on 22 September 1791 inNewington Butts

Newington Butts is a former hamlet, now an area of the London Borough of Southwark, London, England, that gives its name to a segment of the A3 road running south-west from the Elephant and Castle junction. The road continues as Kennington Park ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, which is now part of the London Borough of Southwark

The London Borough of Southwark ( ) in South London forms part of Inner London and is connected by bridges across the River Thames to the City of London and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It was created in 1965 when three smaller council ...

. His family was not well off. His father, James, was a member of the Glasite

The Glasites or Glassites were a small Christian church founded in about 1730 in Scotland by John Glas.John Glas preached supremacy of God's word (Bible) over allegiance to Church and state to his congregation in Tealing near Dundee in July 172 ...

sect of Christianity. James Faraday moved his wife, Margaret (née Hastwell), and two children to London during the winter of 1790 from Outhgill

Outhgill is a hamlet in Mallerstang, Cumbria, England. It lies about south of Kirkby Stephen.

It is the main hamlet in the dale of Mallerstang (a civil parish) which retains the Norsemen, Norse pattern of its original settlement: a series of ...

in Westmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland''R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref>) is an area of North West England which was Historic counties of England, historically a county. People of the area ...

, where he had been an apprentice to the village blacksmith. Michael was born in the autumn of the following year, the third of four children. The young Michael Faraday, having only the most basic school education, had to educate himself.

At the age of 14, he became an apprentice to George Riebau, a local bookbinder and bookseller in Blandford Street. During his seven-year apprenticeship Faraday read many books, including Isaac Watts

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674 – 25 November 1748) was an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician. He was a prolific and popular hymn writer and is credited with some 750 hymns. His works include " When I Survey th ...

's ''The Improvement of the Mind'', and he enthusiastically implemented the principles and suggestions contained therein. During this period, Faraday held discussions with his peers in the City Philosophical Society, where he attended lectures about various scientific topics. He also developed an interest in science, especially in electricity. Faraday was particularly inspired by the book ''Conversations on Chemistry'' by Jane Marcet.

Adult life

In 1812, at the age of 20 and at the end of his apprenticeship, Faraday attended lectures by the eminent English chemistHumphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several Chemical element, e ...

of the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

and the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and John Tatum, founder of the City Philosophical Society. Many of the tickets for these lectures were given to Faraday by William Dance, who was one of the founders of the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

. Faraday subsequently sent Davy a 300-page book based on notes that he had taken during these lectures. Davy's reply was immediate, kind, and favourable. In 1813, when Davy damaged his eyesight in an accident with nitrogen trichloride

Nitrogen trichloride, also known as trichloramine, is the chemical compound with the formula . This yellow, oily, and explosive liquid is most commonly encountered as a product of chemical reactions between ammonia-derivatives and chlorine (for ex ...

, he decided to employ Faraday as an assistant. Coincidentally one of the Royal Institution's assistants, John Payne, was sacked and Sir Humphry Davy had been asked to find a replacement; thus he appointed Faraday as Chemical Assistant at the Royal Institution on 1 March 1813. Very soon, Davy entrusted Faraday with the preparation of nitrogen trichloride samples, and they both were injured in an explosion of this very sensitive substance.

Faraday married Sarah Barnard (1800–1879) on 12 June 1821. They met through their families at the Sandemanian

The Glasites or Glassites were a small Christian church founded in about 1730 in Scotland by John Glas.John Glas preached supremacy of God's word (Bible) over allegiance to Church and state to his congregation in Tealing near Dundee in July 172 ...

church, and he confessed his faith to the Sandemanian congregation the month after they were married. They had no children. Faraday was a devout Christian; his Sandemanian denomination was an offshoot of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

. Well after his marriage, he served as deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

and for two terms as an elder in the meeting house of his youth. His church was located at Paul's Alley in the Barbican

A barbican (from ) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe

Medieval Europeans typically b ...

. This meeting house relocated in 1862 to Barnsbury

Barnsbury is an area of north London in the London Borough of Islington, within the N1 and N7 postal districts.

History

The name is a syncopated form of ''Bernersbury'' (1274), being so called after the Berners family: powerful medieval ...

Grove, Islington

Islington ( ) is an inner-city area of north London, England, within the wider London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's #Islington High Street, High Street to Highbury Fields ...

; this North London location was where Faraday served the final two years of his second term as elder prior to his resignation from that post. Biographers have noted that "a strong sense of the unity of God and nature pervaded Faraday's life and work."

Later life

In June 1832, the

In June 1832, the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

granted Faraday an honorary Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; ) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher doctorate usually awarded on the basis of except ...

degree. During his lifetime, he was offered a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in recognition for his services to science, which he turned down on religious grounds, believing that it was against the word of the Bible to accumulate riches and pursue worldly reward, and stating that he preferred to remain "plain Mr Faraday to the end". Elected a Fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1824, he twice refused to become President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

. He became the first Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in 1833.

In 1832, Faraday was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

in 1838. In 1840, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

. He was one of eight foreign members elected to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1844. In 1849 he was elected as associated member to the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, which two years later became the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (, KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed in the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam.

In addition to various advisory a ...

and he was subsequently made foreign member.

Faraday had a

Faraday had a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

in 1839 but eventually returned to his investigations into electromagnetism. In 1848, as a result of representations by the Prince Consort

A prince consort is the husband of a monarch who is not a monarch in his own right. In recognition of his status, a prince consort may be given a formal title, such as ''prince''. Most monarchies do not allow the husband of a queen regnant to be ...

, Faraday was awarded a grace and favour

A grace-and-favour home is a residential property owned by a monarch, government, or other owner and leased rent-free to a person as part of the perquisites of their employment, or in gratitude for services rendered.

Usage of the term is chief ...

house in Hampton Court

Hampton Court Palace is a Listed building, Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. Opened to the public, the palace is managed by Historic Royal ...

in Middlesex, free of all expenses and upkeep. This was the Master Mason's House, later called Faraday House, and now No. 37 Hampton Court Road. In 1858 Faraday retired to live there.

Having provided a number of various service projects for the British government, when asked by the government to advise on the production of chemical weapons for use in the

Having provided a number of various service projects for the British government, when asked by the government to advise on the production of chemical weapons for use in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

(1853–1856), Faraday refused to participate, citing ethical reasons. He also refused offers to publish his lectures, believing that they would lose impact if not accompanied by the live experiments. His reply to an offer from a publisher in a letter ends with: "I have always loved science more than money & because my occupation is almost entirely personal I cannot afford to get rich."

Faraday died at his house at Hampton Court

Hampton Court Palace is a Listed building, Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. Opened to the public, the palace is managed by Historic Royal ...

on 25 August 1867, aged 75. He had some years before turned down an offer of burial in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

upon his death, but he has a memorial plaque there, near Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

's tomb. Faraday was interred in the dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

s' (non-Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

) section of Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

.

Scientific achievements

Chemistry

Faraday's earliest chemical work was as an assistant to

Faraday's earliest chemical work was as an assistant to Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several Chemical element, e ...

. Faraday was involved in the study of chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

; he discovered two new compounds of chlorine and carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

: hexachloroethane

Hexachloroethane (perchloroethane) is an organochlorine compound with the chemical formula . Its structure is . It is a white or colorless solid at room temperature with a camphor-like odor. It has been used by the military in smoke compositions, ...

which he made via the chlorination of ethylene

Ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon–carbon bond, carbon–carbon doub ...

and carbon tetrachloride

Carbon tetrachloride, also known by many other names (such as carbon tet for short and tetrachloromethane, also IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, recognised by the IUPAC), is a chemical compound with the chemical formula CCl4. It is a n ...

from the decomposition of the former. He also conducted the first rough experiments on the diffusion of gases, a phenomenon that was first pointed out by John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

. The physical importance of this phenomenon was more fully revealed by Thomas Graham Thomas Graham may refer to:

Politicians and diplomats

*Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch (1748–1843), British politician and soldier

* Thomas Graham Jr. (diplomat) (born 1933), nuclear expert and senior U.S. diplomat

*Sir Thomas Graham (barriste ...

and Joseph Loschmidt. Faraday succeeded in liquefying several gases, investigated the alloys of steel, and produced several new kinds of glass intended for optical purposes. A specimen of one of these heavy glasses subsequently became historically important; when the glass was placed in a magnetic field Faraday determined the rotation of the plane of polarisation of light. This specimen was also the first substance found to be repelled by the poles of a magnet.

Faraday invented an early form of what was to become the Bunsen burner

A Bunsen burner, named after Robert Bunsen, is a kind of ambient air gas burner used as laboratory equipment; it produces a single open gas flame, and is used for heating, sterilization, and combustion.

The gas can be natural gas (which is main ...

, which is still in practical use in science laboratories around the world as a convenient source of heat.

Faraday worked extensively in the field of chemistry, discovering chemical substances such as benzene

Benzene is an Organic compound, organic chemical compound with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar hexagonal Ring (chemistry), ring with one hyd ...

(which he called bicarburet of hydrogen) and liquefying gases such as chlorine. The liquefying of gases helped to establish that gases are the vapours of liquids possessing a very low boiling point and gave a more solid basis to the concept of molecular aggregation. In 1820 Faraday reported the first synthesis of compounds made from carbon and chlorine, C2Cl6 and CCl4, and published his results the following year. Faraday also determined the composition of the chlorine clathrate hydrate

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, or hydrates, are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped ins ...

, which had been discovered by Humphry Davy in 1810. Faraday is also responsible for discovering the laws of electrolysis

Faraday's laws of electrolysis are quantitative relationships based on the electrochemical research published by Michael Faraday in 1833.

First law

Michael Faraday reported that the mass () of a substance deposited or liberated at an electrod ...

, and for popularising terminology such as anode

An anode usually is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, which is usually an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the devic ...

, cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device such as a lead-acid battery. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. Conventional curren ...

, electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or a gas). In electrochemical cells, electrodes are essential parts that can consist of a varie ...

, and ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

, terms proposed in large part by William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

.

Faraday was the first to report what later came to be called metallic nanoparticles

A nanoparticle or ultrafine particle is a particle of matter 1 to 100 nanometres (nm) in diameter. The term is sometimes used for larger particles, up to 500 nm, or fibers and tubes that are less than 100 nm in only two directions. At ...

. In 1857 he discovered that the optical properties of gold colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s differed from those of the corresponding bulk metal. This was probably the first reported observation of the effects of quantum

In physics, a quantum (: quanta) is the minimum amount of any physical entity (physical property) involved in an interaction. The fundamental notion that a property can be "quantized" is referred to as "the hypothesis of quantization". This me ...

size, and might be considered to be the birth of nanoscience

Nanotechnology is the manipulation of matter with at least one dimension sized from 1 to 100 nanometers (nm). At this scale, commonly known as the nanoscale, surface area and quantum mechanical effects become important in describing propertie ...

.

Electricity and magnetism

Faraday is best known for his work on electricity and magnetism. His first recorded experiment was the construction of avoltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. Each copper–zinc pair had a spacer in the middle, made of cardboard or felt soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the ...

with seven British halfpenny coins, stacked together with seven discs of sheet zinc, and six pieces of paper moistened with salt water. With this pile he passed the electric current

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge c ...

through a solution of sulfate of magnesia and succeeded in decomposing the chemical compound (recorded in first letter to Abbott, 12 July 1812).

In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist

In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted (; 14 August 1777 – 9 March 1851), sometimes Transliteration, transliterated as Oersted ( ), was a Danish chemist and physicist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields. This phenomenon is known as ...

discovered the phenomenon of electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

, Davy and William Hyde Wollaston

William Hyde Wollaston (; 6 August 1766 – 22 December 1828) was an English chemist and physicist who is famous for discovering the chemical elements palladium and rhodium. He also developed a way to process platinum ore into malleable i ...

tried, but failed, to design an electric motor

An electric motor is a machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a electromagnetic coil, wire winding to gene ...

. Faraday, having discussed the problem with the two men, went on to build two devices to produce what he called "electromagnetic rotation". One of these, now known as the homopolar motor

A homopolar motor is a direct current electric motor with two magnetic poles, the conductors of which always cut unidirectional lines of magnetic flux by rotating a conductor around a fixed axis so that the conductor is at right angles to a s ...

, caused a continuous circular motion that was engendered by the circular magnetic force around a wire that extended into a pool of mercury wherein was placed a magnet; the wire would then rotate around the magnet if supplied with current from a chemical battery. These experiments and inventions formed the foundation of modern electromagnetic technology. In his excitement, Faraday published results without acknowledging his work with either Wollaston or Davy. The resulting controversy within the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

strained his mentor relationship with Davy and may well have contributed to Faraday's assignment to other activities, which consequently prevented his involvement in electromagnetic research for several years.

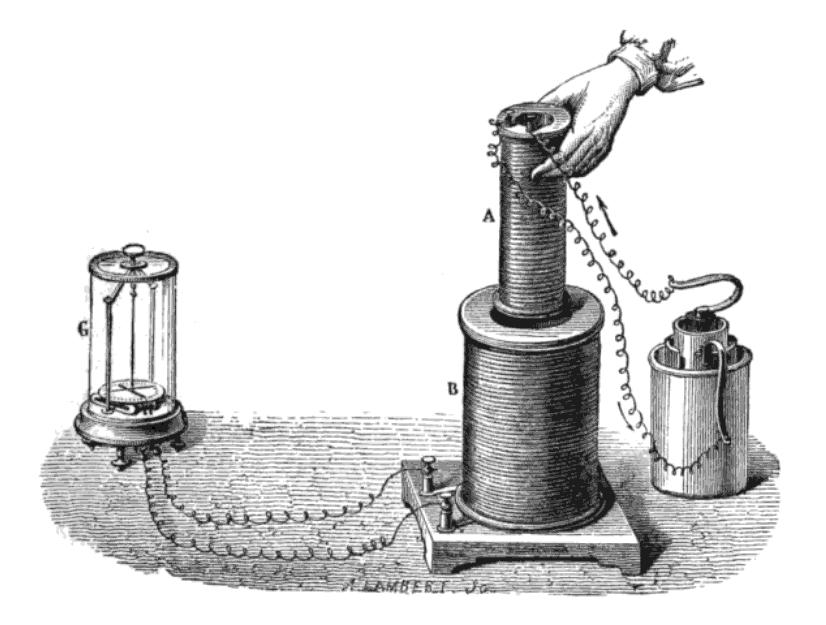

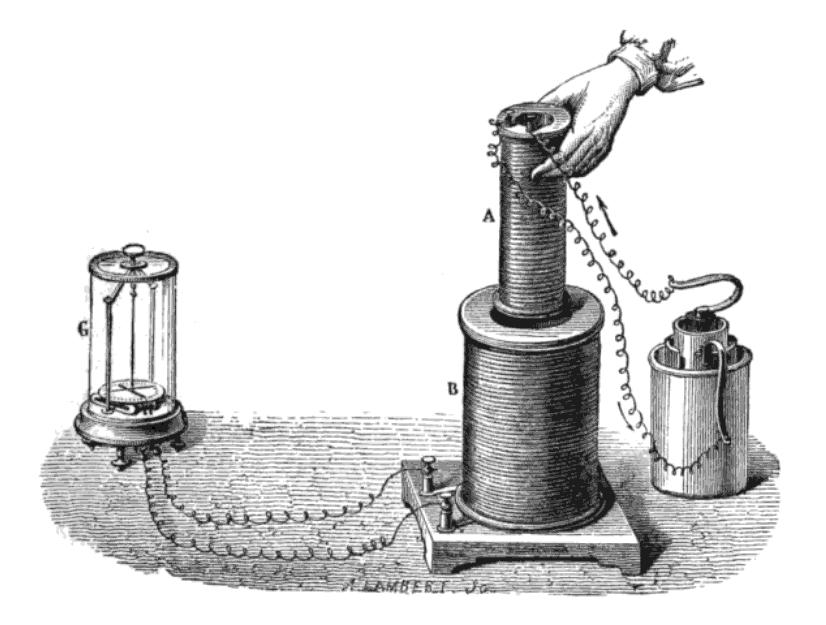

From his initial discovery in 1821, Faraday continued his laboratory work, exploring electromagnetic properties of materials and developing requisite experience. In 1824, Faraday briefly set up a circuit to study whether a magnetic field could regulate the flow of a current in an adjacent wire, but he found no such relationship. This experiment followed similar work conducted with light and magnets three years earlier that yielded identical results. During the next seven years, Faraday spent much of his time perfecting his recipe for optical quality (heavy) glass, borosilicate of lead, which he used in his future studies connecting light with magnetism. In his spare time, Faraday continued publishing his experimental work on optics and electromagnetism; he conducted correspondence with scientists whom he had met on his journeys across Europe with Davy, and who were also working on electromagnetism. Two years after the death of Davy, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered

From his initial discovery in 1821, Faraday continued his laboratory work, exploring electromagnetic properties of materials and developing requisite experience. In 1824, Faraday briefly set up a circuit to study whether a magnetic field could regulate the flow of a current in an adjacent wire, but he found no such relationship. This experiment followed similar work conducted with light and magnets three years earlier that yielded identical results. During the next seven years, Faraday spent much of his time perfecting his recipe for optical quality (heavy) glass, borosilicate of lead, which he used in his future studies connecting light with magnetism. In his spare time, Faraday continued publishing his experimental work on optics and electromagnetism; he conducted correspondence with scientists whom he had met on his journeys across Europe with Davy, and who were also working on electromagnetism. Two years after the death of Davy, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

, recording in his laboratory diary on 28 October 1831 that he was "making many experiments with the great magnet of the Royal Society".

Faraday's breakthrough came when he wrapped two insulated coils of wire around an iron ring, and found that, upon passing a current through one coil, a momentary current was induced in the other coil. This phenomenon is now known as

Faraday's breakthrough came when he wrapped two insulated coils of wire around an iron ring, and found that, upon passing a current through one coil, a momentary current was induced in the other coil. This phenomenon is now known as mutual inductance

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The electric current produces a magnetic field around the conductor. The magnetic field strength depends on the magnitude of the ...

. The iron ring-coil apparatus is still on display at the Royal Institution. In subsequent experiments, he found that if he moved a magnet through a loop of wire an electric current flowed in that wire. The current also flowed if the loop was moved over a stationary magnet. His demonstrations established that a changing magnetic field produces an electric field; this relation was modelled mathematically by James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

as Faraday's law, which subsequently became one of the four Maxwell equations, and which have in turn evolved into the generalization known today as field theory. Faraday would later use the principles he had discovered to construct the electric dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos employed electromagnets for self-starting by using residual magnetic field left in the iron cores ...

, the ancestor of modern power generators and the electric motor.

In 1832, he completed a series of experiments aimed at investigating the fundamental nature of electricity; Faraday used " static", batteries, and "

In 1832, he completed a series of experiments aimed at investigating the fundamental nature of electricity; Faraday used " static", batteries, and "animal electricity

Galvanism is a term invented by the late 18th-century physicist and chemist Alessandro Volta to refer to the generation of electric current by chemical action. The term also came to refer to the discoveries of its namesake, Luigi Galvani, specifi ...

" to produce the phenomena of electrostatic attraction, electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

, magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, etc. He concluded that, contrary to the scientific opinion of the time, the divisions between the various "kinds" of electricity were illusory. Faraday instead proposed that only a single "electricity" exists, and the changing values of quantity and intensity (current and voltage) would produce different groups of phenomena.

Near the end of his career, Faraday proposed that electromagnetic forces extended into the empty space around the conductor. This idea was rejected by his fellow scientists, and Faraday did not live to see the eventual acceptance of his proposition by the scientific community. It would be another half a century before electricity was used in technology, with the West End's Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy ...

, fitted with the incandescent light bulb

An incandescent light bulb, also known as an incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe, is an electric light that produces illumination by Joule heating a #Filament, filament until it incandescence, glows. The filament is enclosed in a ...

developed by Sir Joseph Swan

Sir Joseph Wilson Swan Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (31 October 1828 – 27 May 1914) was an English physicist, chemist, and inventor. He is known as an independent early developer of a successful incandescent light bulb, and is respon ...

, the first public building in the world to be lit by electricity. As recorded by the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, "Faraday invented the generator in 1831 but it took nearly 50 years before all the technology, including Joseph Swan's incandescent filament light bulbs used here, came into common use".

Diamagnetism

In 1845, Faraday discovered that many materials exhibit a weak repulsion from a magnetic field: an effect he termed

In 1845, Faraday discovered that many materials exhibit a weak repulsion from a magnetic field: an effect he termed diamagnetism

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnet ...

.

Faraday also discovered that the plane of polarization

Polarization or polarisation may refer to:

Mathematics

*Polarization of an Abelian variety, in the mathematics of complex manifolds

*Polarization of an algebraic form, a technique for expressing a homogeneous polynomial in a simpler fashion by ...

of linearly polarised light can be rotated by the application of an external magnetic field aligned with the direction in which the light is moving. This is now termed the Faraday effect

The Faraday effect or Faraday rotation, sometimes referred to as the magneto-optic Faraday effect (MOFE), is a physical magneto-optical phenomenon. The Faraday effect causes a polarization rotation which is proportional to the projection of the ...

. In Sept 1845 he wrote in his notebook, "I have at last succeeded in ''illuminating a magnetic curve'' or '' line of force'' and in ''magnetising a ray of light''".

Later on in his life, in 1862, Faraday used a spectroscope to search for a different alteration of light, the change of spectral lines by an applied magnetic field. The equipment available to him was, however, insufficient for a definite determination of spectral change. Pieter Zeeman

Pieter Zeeman ( ; ; 25 May 1865 – 9 October 1943) was a Dutch physicist who shared the 1902 Nobel Prize in Physics with Hendrik Lorentz for their discovery and theoretical explanation of the Zeeman effect.

Childhood and youth

Pieter Zeeman was ...

later used an improved apparatus to study the same phenomenon, publishing his results in 1897 and receiving the 1902 Nobel Prize in Physics for his success. In both his 1897 paper and his Nobel acceptance speech, Zeeman made reference to Faraday's work.

Faraday cage

In his work on static electricity,Faraday's ice pail experiment

Faraday's ice pail experiment is a simple electrostatics Scientific experiment, experiment performed in 1843 by British scientist Michael Faraday that demonstrates the effect of electrostatic induction on a Electrical conductance, conducting cont ...

demonstrated that the charge resided only on the exterior of a charged conductor, and exterior charge had no influence on anything enclosed within a conductor. This is because the exterior charges redistribute such that the interior fields emanating from them cancel one another. This shielding effect is used in what is now known as a Faraday cage

A Faraday cage or Faraday shield is an enclosure used to block some electromagnetic fields. A Faraday shield may be formed by a continuous covering of conductive material, or in the case of a Faraday cage, by a mesh of such materials. Faraday cag ...

. In January 1836, Faraday had put a wooden frame, 12 ft square, on four glass supports and added paper walls and wire mesh. He then stepped inside and electrified it. When he stepped out of his electrified cage, Faraday had shown that electricity was a force, not an imponderable fluid as was believed at the time.

Royal Institution and public service

Faraday had a long association with the

Faraday had a long association with the Royal Institution of Great Britain

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

. He was appointed Assistant Superintendent of the House of the Royal Institution in 1821. He was elected a Fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1824. In 1825, he became Director of the Laboratory of the Royal Institution. Six years later, in 1833, Faraday became the first Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution of Great Britain

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, a position to which he was appointed for life without the obligation to deliver lectures. His sponsor and mentor was John 'Mad Jack' Fuller, who created the position at the Royal Institution for Faraday.

Beyond his scientific research into areas such as chemistry, electricity, and magnetism at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, Faraday undertook numerous, and often time-consuming, service projects for private enterprise and the British government. This work included investigations of explosions in coal mines, being an expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

in court, and along with two engineers from Chance Brothers

Chance Brothers and Company was an English glassworks originally based in Spon Lane, Smethwick, West Midlands (county), West Midlands (formerly in Staffordshire), in England. It was a leading glass manufacturer and a pioneer of British glassma ...

, the preparation of high-quality optical glass, which was required by Chance for its lighthouses. In 1846, together with Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, he produced a lengthy and detailed report on a serious explosion

An explosion is a rapid expansion in volume of a given amount of matter associated with an extreme outward release of energy, usually with the generation of high temperatures and release of high-pressure gases. Explosions may also be generated ...

in the colliery at Haswell, County Durham, which killed 95 miners. Their report was a meticulous forensic investigation

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

and indicated that coal dust

Coal dust is a fine-powdered form of coal which is created by the crushing, grinding, or pulverizer, pulverization of coal rock. Because of the brittle nature of coal, coal dust can be created by mining, transporting, or mechanically handling it. ...

contributed to the severity of the explosion. The first-time explosions had been linked to dust, Faraday gave a demonstration during a lecture on how ventilation could prevent it. The report should have warned coal owners of the hazard of coal dust explosions, but the risk was ignored for over 60 years until the 1913 Senghenydd Colliery Disaster.

As a respected scientist in a nation with strong maritime interests, Faraday spent extensive amounts of time on projects such as the construction and operation of

As a respected scientist in a nation with strong maritime interests, Faraday spent extensive amounts of time on projects such as the construction and operation of lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lens (optics), lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Ligh ...

s and protecting the bottoms of ships from corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

. His workshop still stands at Trinity Buoy Wharf above the Chain and Buoy Store, next to London's only lighthouse where he carried out the first experiments in electric lighting for lighthouses.

Faraday was also active in what would now be called environmental science, or engineering. He investigated industrial pollution at Swansea

Swansea ( ; ) is a coastal City status in the United Kingdom, city and the List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, second-largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of ...

and was consulted on air pollution at the Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's official maker of British coins. It is currently located in Llantrisant, Wales, where it moved in 1968.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly ow ...

. In July 1855, Faraday wrote a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' on the subject of the foul condition of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

, which resulted in an often-reprinted cartoon in '' Punch''. (See also The Great Stink

The Great Stink was an event in Central London during July and August 1858 in which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been ...

).Faraday, Michael (9 July 1855). "The State of the Thames", ''The Times''. p. 8.

Faraday assisted with the planning and judging of exhibits for the

Faraday assisted with the planning and judging of exhibits for the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851 in Hyde Park, London. He also advised the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of more than 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current di ...

on the cleaning and protection of its art collection, and served on the National Gallery Site Commission in 1857. Education was another of Faraday's areas of service; he lectured on the topic in 1854 at the Royal Institution, and, in 1862, he appeared before a Public Schools Commission to give his views on education in Great Britain. Faraday also weighed in negatively on the public's fascination with table-turning

Table-turning (also known as table-tapping, table-tipping or table-tilting) is a type of séance in which participants sit around a Table (furniture), table, place their hands on it, and wait for rotations. The table was purportedly made to serve ...

, mesmerism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, is a theory invented by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century. It posits the existence of an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all living things, including humans ...

, and seances, and in so doing chastised both the public and the nation's educational system.

Before his famous Christmas lectures, Faraday delivered chemistry lectures for the City Philosophical Society from 1816 to 1818 in order to refine the quality of his lectures.

Between 1827 and 1860 at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in London, Faraday gave a series of nineteen Christmas lectures for young people, a series which continues today. The objective of the lectures was to present science to the general public in the hopes of inspiring them and generating revenue for the Royal Institution. They were notable events on the social calendar among London's gentry. Over the course of several letters to his close friend Benjamin Abbott, Faraday outlined his recommendations on the art of lecturing, writing "a flame should be lighted at the commencement and kept alive with unremitting splendour to the end". His lectures were joyful and juvenile, he delighted in filling soap bubbles with various gasses (in order to determine whether or not they are magnetic), but the lectures were also deeply philosophical. In his lectures he urged his audiences to consider the mechanics of his experiments: "you know very well that ice floats upon water ... Why does the ice float? Think of that, and philosophise". The subjects in his lectures consisted of Chemistry and Electricity, and included: 1841: ''The Rudiments of Chemistry'', 1843: ''First Principles of Electricity'', 1848: '' The Chemical History of a Candle'', 1851: ''Attractive Forces'', 1853: ''Voltaic Electricity'', 1854: ''The Chemistry of Combustion'', 1855: ''The Distinctive Properties of the Common Metals'', 1857: ''Static Electricity'', 1858: ''The Metallic Properties'', 1859: ''The Various Forces of Matter and their Relations to Each Other''.

Commemorations

A statue of Michael Faraday stands in Savoy Place, London, outside theInstitution of Engineering and Technology

The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) is a multidisciplinary professional engineering institution. The IET was formed in 2006 from two separate institutions: the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), dating back to 1871,Engin ...

. The Faraday Memorial, designed by brutalist

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the b ...

architect Rodney Gordon and completed in 1961, is at the Elephant & Castle

Elephant and Castle is an area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark. The name also informally refers to much of Walworth and Newington, due to the proximity of the London Underground station of the same name. The nam ...

gyratory system, near Faraday's birthplace at Newington Butts

Newington Butts is a former hamlet, now an area of the London Borough of Southwark, London, England, that gives its name to a segment of the A3 road running south-west from the Elephant and Castle junction. The road continues as Kennington Park ...

, London. Faraday School is located on Trinity Buoy Wharf where his workshop still stands above the Chain and Buoy Store, next to London's only lighthouse. Faraday Gardens is a small park in Walworth

Walworth ( ) is a district of South London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. It adjoins Camberwell to the south and Elephant and Castle to the north, and is south-east of Charing Cross.

Major streets in Walworth include the ...

, London, not far from his birthplace at Newington Butts. It lies within the local council ward of Faraday in the London Borough of Southwark

The London Borough of Southwark ( ) in South London forms part of Inner London and is connected by bridges across the River Thames to the City of London and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It was created in 1965 when three smaller council ...

. Michael Faraday Primary school is situated on the Aylesbury Estate in Walworth

Walworth ( ) is a district of South London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. It adjoins Camberwell to the south and Elephant and Castle to the north, and is south-east of Charing Cross.

Major streets in Walworth include the ...

.

A building at London South Bank University

London South Bank University (LSBU) is a public university in Elephant and Castle, London. It is based in the London Borough of Southwark, near the South Bank of the River Thames, from which it takes its name. Founded in 1892 as the Borough Po ...

, which houses the institute's electrical engineering departments is named the Faraday Wing, due to its proximity to Faraday's birthplace in Newington Butts

Newington Butts is a former hamlet, now an area of the London Borough of Southwark, London, England, that gives its name to a segment of the A3 road running south-west from the Elephant and Castle junction. The road continues as Kennington Park ...

. A hall at Loughborough University

Loughborough University (abbreviated as ''Lough'' or ''Lboro'' for Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a public university, public research university in the market town of Loughborough, Leicestershire, England. It has been a university sinc ...

was named after Faraday in 1960. Near the entrance to its dining hall is a bronze casting, which depicts the symbol of an electrical transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

, and inside there hangs a portrait, both in Faraday's honour. An eight-storey building at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

's science & engineering campus is named for Faraday, as is a recently built hall of accommodation at Brunel University

Brunel University of London (BUL) is a public research university located in the Uxbridge area of London, England. It is named after Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a Victorian engineer and pioneer of the Industrial Revolution. It became a university ...

, the main engineering building at Swansea University

Swansea University () is a public university, public research university located in Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom.

It was chartered as University College of Swansea in 1920, as the fourth college of the University of Wales. In 1996, it chang ...

, and the instructional and experimental physics building at Northern Illinois University

Northern Illinois University (NIU) is a public research university in DeKalb, Illinois, United States. It was founded as "Northern Illinois State Normal School" in 1895 by Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld, initially to provide the state with c ...

. The former UK Faraday Station in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

was named after him.

Streets named for Faraday can be found in many British cities (e.g., London, Glenrothes

Glenrothes ( ; ; , ) is a town situated in the heart of Fife, in east-central Scotland. It had a population of 39,277 in the 2011 census, making it the third largest settlement in Fife and the 18th most populous locality in Scotland. Glenroth ...

, Swindon

Swindon () is a town in Wiltshire, England. At the time of the 2021 Census the population of the built-up area was 183,638, making it the largest settlement in the county. Located at the northeastern edge of the South West England region, Swi ...

, Basingstoke

Basingstoke ( ) is a town in Hampshire, situated in south-central England across a valley at the source of the River Loddon on the western edge of the North Downs. It is the largest settlement in Hampshire without city status in the United King ...

, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located south-east of Sheffield and nor ...

, Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

, Kirkby

Kirkby ( ) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley, Merseyside, England. The town, Historic counties of England, historically in Lancashire, has a size of is north of Huyton and north-east of Liverpool. The population in 2016 wa ...

, Crawley

Crawley () is a town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in West Sussex, England. It is south of London, north of Brighton and Hove, and north-east of the county town of Chichester. Crawley covers an area of and had a populat ...

, Newbury, Swansea