Eugene O’Neill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier associated with

O'Neill was born on October 16, 1888, in a hotel, the Barrett House, on what was then Longacre Square (now

O'Neill was born on October 16, 1888, in a hotel, the Barrett House, on what was then Longacre Square (now

''Eugene O'Neill: A Life in Four Acts'', Yale University Press, 2014

The O'Neill family reunited for summers at the Monte Cristo Cottage in

In an early one-act play, ''The Web'', written in 1913, O'Neill first explored the darker themes that he later thrived on. Here he focused on the brothel world and the lives of prostitutes, which also play a role in some fourteen of his later plays. In particular, he memorably included the birth of an infant into the world of prostitution. At the time, such themes constituted a huge innovation, as these sides of life had never before been presented with such success.

O'Neill's first published play, '' Beyond the Horizon'', opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the

In an early one-act play, ''The Web'', written in 1913, O'Neill first explored the darker themes that he later thrived on. Here he focused on the brothel world and the lives of prostitutes, which also play a role in some fourteen of his later plays. In particular, he memorably included the birth of an infant into the world of prostitution. At the time, such themes constituted a huge innovation, as these sides of life had never before been presented with such success.

O'Neill's first published play, '' Beyond the Horizon'', opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the  He was also part of the modern movement to partially revive the classical heroic

He was also part of the modern movement to partially revive the classical heroic

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director, and producer

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director, and producer

After suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe

After suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe  O'Neill died at the Sheraton Hotel (now

O'Neill died at the Sheraton Hotel (now

Works by Eugene O'Neill

a

Project Gutenberg Australia

* * *

Works by Eugene O'Neill

(public domain in Canada) ;Physical collections

Eugene O'Neill Collection.

Carlotta O'Neill notebook of letters and photographs, 1927-1954

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

Harley Hammerman Collection on Eugene O'Neill

Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, Washington University in St. Louis.

Louis Sheaffer Collection of Eugene O'NeillLinda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives

Connecticut College. ;Analysis and editorials

Haunted by Eugene O'Neill

��Article in ''BU Today'', September 29, 2009

Eugene O'Neill: the sailor, the sickness, the stage

from th

Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

;Seminal dissertations by scholars

* Eugene O’Neill e Lars Norén: “A Swedish-American Kinship” by Anna Airoldi * Postmodern Considerations of Nietzstchean Perspectivism in Selected Works of Eugene O'Neill by Eric Mathew Levin * The Pipe Dreams and Primitivism: Eugene O'Neill and the Rhetoric of Ethnicity by Donald P. Gagnon * The Discovery of the Self in Eugene O'Neill's ''The Emperor Jones'' and ''The Iceman Cometh'' and Joseph Conrad's ''Heart of Darkness'' and "To-morrow": A Comparative Study by Mohamed Amine Dekkiche * "Darker Brother" in Stage-Center: Eugene O'Neill's Quest for Racial Equity in Three Decades (1913-1939) of American Drama by Shahed Ahmed ;External entries * * * *

archive

;Other sources

Eugene O'Neill official website

Casa Genotta official website

American Experience - Eugene O'Neill: A Documentary Film on PBS

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Oneill, Eugene 1888 births 1953 deaths Eugene O'Neill O'Neill, Eugene American agnostics American Nobel laureates American people of Irish descent American writers of Irish descent Expressionist dramatists and playwrights Industrial Workers of the World members Irish-American history Laurence Olivier Award winners Modernist theatre Nobel laureates in Literature People from Danville, California People from Greenwich Village Writers from Manhattan Writers from New London, Connecticut People from Point Pleasant, New Jersey People from Provincetown, Massachusetts Writers from Ridgefield, Connecticut People with Parkinson's disease Princeton University alumni Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Tony Award winners Deaths from pneumonia in Massachusetts Members of The Lambs Club Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Members of the American Philosophical Society Writers of Irish descent Chaplin family

Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

, Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright, poet and actor. Ibsen is considered the world's pre-eminent dramatist of the 19th century and is often referred to as "the father of modern drama." He pioneered ...

, and Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (; ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist, and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than 60 play ...

. The tragedy '' Long Day's Journey into Night'' is often included on lists of the finest U.S. plays in the 20th century, alongside Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983), known by his pen name Tennessee Williams, was an American playwright and screenwriter. Along with contemporaries Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the three ...

's ''A Streetcar Named Desire

''A Streetcar Named Desire'' is a play written by Tennessee Williams and first performed on Broadway on December 3, 1947. The play dramatizes the experiences of Blanche DuBois, a former Southern belle who, after encountering a series of pe ...

'' and Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are '' All My Sons'' (1947), '' Death of a Salesman'' (1 ...

's ''Death of a Salesman

''Death of a Salesman'' is a 1949 stage play written by the American playwright Arthur Miller. The play premiered on Broadway in February 1949, running for 742 performances. It is a two-act tragedy set in late 1940s Brooklyn told through a ...

''. He was awarded the 1936 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1936 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the American playwright Eugene O'Neill (1888–1953) "for the power, honesty and deep-felt emotions of his dramatic works, which embody an original concept of tragedy". He is the second American to ...

. O'Neill is also the only playwright to win four Pulitzer Prizes for Drama.

O'Neill's plays were among the first to include speeches in American English vernacular and involve characters on the fringes of society. They struggle to maintain their hopes and aspirations, ultimately sliding into disillusion and despair. Of his very few comedies, only one is well-known ('' Ah, Wilderness!'').The Eugene O'Neill Foundation newsletter: "''Now I Ask You'', along with ''The Movie Man'', ... is the only surviving comedy from O'Neill's early years." Nearly all of his other plays involve some degree of tragedy and personal pessimism.

Early life

O'Neill was born on October 16, 1888, in a hotel, the Barrett House, on what was then Longacre Square (now

O'Neill was born on October 16, 1888, in a hotel, the Barrett House, on what was then Longacre Square (now Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and Neighborhoods in New York City, neighborhood in the Midtown Manhattan section of New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway (Manhattan), ...

) in New York City. A commemorative plaque was first dedicated there in 1957. The site is now occupied by 1500 Broadway

1500 Broadway (also known as Times Square Plaza) is an office building on Times Square in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, New York. Completed in 1972 by Arlen Realty & Development Corporation, the 33-story building is tall. The building repl ...

, which houses offices, shops and the ABC Studios

ABC Signature was a production arm of the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), which is a subsidiary of Disney Television Studios, a sub-division of the Disney Entertainment business segment and division of The Walt Disney Company. The studio's ...

.

He was the son of Irish immigrant actor James O'Neill and Mary Ellen Quinlan, who was also of Irish descent. His father suffered from alcoholism; his mother from an addiction to morphine, prescribed to relieve the pains of the difficult birth of Eugene, who was her third son. Because his father was often on tour with a theatrical company, accompanied by Eugene's mother, in 1895 O'Neill was sent to St. Aloysius Academy for Boys, a Catholic boarding school in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. In 1900, he became a day student at the De La Salle Institute

De La Salle Institute is a private, Catholic, coeducational high school run by the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It was founded by Brother Adjutor o ...

on 59th Street in Manhattan.Dowling, Robert M.''Eugene O'Neill: A Life in Four Acts'', Yale University Press, 2014

The O'Neill family reunited for summers at the Monte Cristo Cottage in

New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

. He also briefly attended Betts Academy in Stamford. He attended Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

for one year. Accounts vary as to why he left. He may have been dropped for attending too few classes, been suspended for "conduct code violations", or "for breaking a window", or according to a more concrete but possibly apocryphal account, because he threw "a beer bottle into the window of Professor Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

", the future president of the United States.

O'Neill spent several years at sea, during which he suffered from depression, alcoholism and despair. Despite this, he had a deep love for the sea and it became a prominent theme in many of his plays, several of which are set on board ships like those on which he worked. O'Neill joined the Marine Transport Workers Union of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW), which was fighting for improved living conditions for the working class using quick 'on the job' direct action. O'Neill's parents and elder brother Jamie (who drank himself to death at the age of 45) died within three years of one another, not long after he had begun to make his mark in the theater.

Career

After returning to New York and living in poverty, O'Neill attempted suicide in 1912 in his room at Jimmy-the-Priest's boarding house and saloon, which — together with the Hell Hole — would one day become the setting for his play '' The Iceman Cometh''. That same year, he and his first wife Kathleen divorced, and he contractedtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. It was during his recovery at a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, is a historic name for a specialised hospital for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments, and convalescence.

Sanatoriums are often in a health ...

— which he came to regard as his "rebirth" — that he determined he would become a playwright. "I want to be an artist or nothing," he said.

After recovering from tuberculosis, he decided to devote himself full-time to writing plays (the events immediately prior to going to the sanatorium are dramatized in his masterpiece, '' Long Day's Journey into Night''). O'Neill had previously been employed by the ''New London Telegraph'', writing poetry as well as reporting. In the fall of 1914, O'Neill studied at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

with George Pierce Baker, who ran a famous course called “Workshop 47” that taught the fundamentals of playwriting, but left after one year.

During the 1910s, O'Neill was a regular on the Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

literary scene, where he also befriended many radicals, most notably Communist Labor Party of America founder John Reed. O'Neill also had a brief romantic relationship with Reed's wife, writer Louise Bryant. O'Neill was portrayed by Jack Nicholson

John Joseph Nicholson (born April 22, 1937) is an American retired actor and filmmaker. Nicholson is widely regarded as one of the greatest actors of the 20th century, often playing rebels fighting against the social structure. Over his five-de ...

in the 1981 film '' Reds'', about the life of John Reed; Louise Bryant was portrayed by Diane Keaton

Diane Keaton (née Hall; born January 5, 1946) is an American actress. She has received List of awards and nominations received by Diane Keaton, various accolades throughout her career spanning over five decades, including an Academy Award, a Bri ...

.

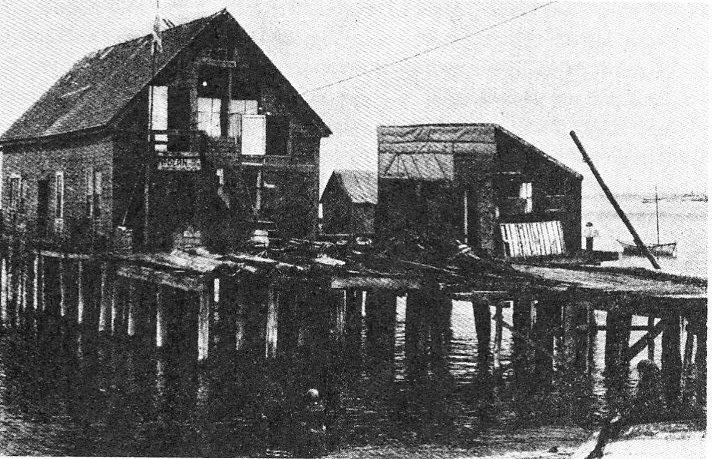

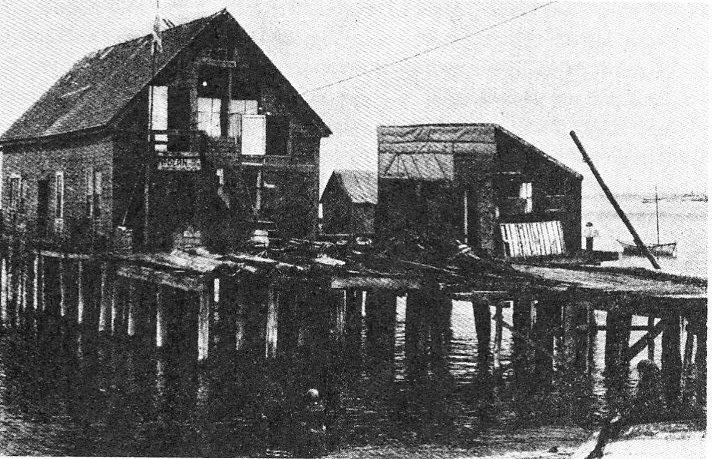

His involvement with the Provincetown Players began in mid-1916. Terry Carlin reported that O'Neill arrived for the summer in Provincetown with "a trunk full of plays", but this was an exaggeration. Susan Glaspell

Susan Keating Glaspell (July 1, 1876 – July 28, 1948) was an American playwright, novelist, journalist and actress. With her husband George Cram Cook, she founded the Provincetown Players, the first modern American theatre company.

First know ...

describes a reading of ''Bound East for Cardiff'' that took place in the living room of Glaspell and her husband George Cram Cook's home on Commercial Street, adjacent to the wharf (pictured) that was used by the Players for their theater: "So Gene took ''Bound East for Cardiff'' out of his trunk, and Freddie Burt read it to us, Gene staying out in the dining-room while reading went on. He was not left alone in the dining-room when the reading had finished." The Provincetown Players performed many of O'Neill's early works in their theaters both in Provincetown and on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

. Some of these early plays, such as ''The Emperor Jones'', began downtown and then moved to Broadway.

In an early one-act play, ''The Web'', written in 1913, O'Neill first explored the darker themes that he later thrived on. Here he focused on the brothel world and the lives of prostitutes, which also play a role in some fourteen of his later plays. In particular, he memorably included the birth of an infant into the world of prostitution. At the time, such themes constituted a huge innovation, as these sides of life had never before been presented with such success.

O'Neill's first published play, '' Beyond the Horizon'', opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the

In an early one-act play, ''The Web'', written in 1913, O'Neill first explored the darker themes that he later thrived on. Here he focused on the brothel world and the lives of prostitutes, which also play a role in some fourteen of his later plays. In particular, he memorably included the birth of an infant into the world of prostitution. At the time, such themes constituted a huge innovation, as these sides of life had never before been presented with such success.

O'Neill's first published play, '' Beyond the Horizon'', opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama

The Pulitzer Prize for Drama is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It is one of the original Pulitzers, for the program was inaugurated in 1917 with seven prizes, four of which were a ...

. His first major hit was '' The Emperor Jones'', which ran on Broadway in 1920 and obliquely commented on the U.S. occupation of Haiti that was a topic of debate in that year's presidential election. His best-known plays include ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a Play (theatre), play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway theatre, Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According ...

'' (Pulitzer Prize 1922), '' Desire Under the Elms'' (1924), '' Strange Interlude'' (Pulitzer Prize 1928), ''Mourning Becomes Electra

''Mourning Becomes Electra'' is a play cycle written by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. The play premiered on Broadway at the Guild Theatre on 26 October 1931 where it ran for 150 performances before closing in March 1932, starring Lee Ba ...

'' (1931), and his only well-known comedy, '' Ah, Wilderness!'', a wistful re-imagining of his youth as he wished it had been.

O'Neill was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in 1935. In 1936, O'Neill received the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

after he had been nominated that year by Henrik Schück, member of the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy (), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is best known as the body t ...

. O'Neill was profoundly influenced by the work of Swedish writer August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (; ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist, and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than 60 pla ...

, and upon receiving the Nobel Prize, dedicated much of his acceptance speech to describing Strindberg's influence on his work. In conversation with Russel Crouse, O'Neill said that "the Strindberg part of the speech is no 'telling tale' to please the Swedes with a polite gesture. It is absolutely sincere. ..And it's absolutely true that I am proud of the opportunity to acknowledge my debt to Strindberg thus publicly to his people". Before the speech was sent to Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

, O'Neill read it to his friend Sophus Keith Winther. As he was reading, he suddenly interrupted himself with the comment: "I wish immortality were a fact, for then some day I would meet Strindberg". When Winther objected that "that would scarcely be enough to justify immortality", O'Neill answered quickly and firmly: "It would be enough for me".

After a ten-year pause, O'Neill's now-renowned play '' The Iceman Cometh'' was produced in 1946. The following year's '' A Moon for the Misbegotten'' failed, and it was decades before coming to be considered as among his best works.

He was also part of the modern movement to partially revive the classical heroic

He was also part of the modern movement to partially revive the classical heroic mask

A mask is an object normally worn on the face, typically for protection, disguise, performance, or entertainment, and often employed for rituals and rites. Masks have been used since antiquity for both ceremonial and practical purposes, ...

from ancient Greek theatre

A theatrical culture flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as p ...

and Japanese Noh theatre in some of his plays, such as '' The Great God Brown'' and '' Lazarus Laughed.''

Family life

O'Neill was married to Kathleen Jenkins from October 2, 1909, to 1912, during which time they had one son, Eugene O'Neill, Jr. (1910–1950). In 1917, O'Neill met Agnes Boulton, a successful writer of commercial fiction, and they married on April 12, 1918. They lived in a home owned by her parents in Point Pleasant, New Jersey, after their marriage. The years of their marriage—during which the couple lived inConnecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

and Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

and had two children, Shane and Oona—are described vividly in her 1958 memoir ''Part of a Long Story''. They divorced on July 2, 1929, after O'Neill abandoned Boulton and the children, for the actress Carlotta Monterey

Carlotta Monterey (born Hazel Nielsen Tharsing; December 28, 1888 – November 18, 1970) was an American stage and film actress. She was the third and final wife of playwright Eugene O'Neill.

Carlotta Monterey was born Hazel Nielsen Tharsing o ...

. O'Neill and Carlotta married less than a month after he officially divorced his previous wife.

In 1929, O'Neill and Monterey moved to the Loire Valley in central France, where they lived in the Château du Plessis in Saint-Antoine-du-Rocher, Indre-et-Loire. During the early 1930s they returned to the United States and lived in Sea Island, Georgia, at a house called Casa Genotta. He moved to Danville, California

The Town of DanvillePronounced is located in the San Ramon Valley in Contra Costa County, California, United States. It is one of the List of municipalities in California, incorporated municipalities in California that use "town" in their nam ...

, in 1937 and lived there until 1944. His house there, ''Tao House'', is today the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site.

In their first years together, Monterey organized O'Neill's life, enabling him to devote himself to writing. She later became addicted to potassium bromide

Potassium bromide ( K Br) is a salt, widely used as an anticonvulsant and a sedative in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with over-the-counter use extending to 1975 in the US. Its action is due to the bromide ion ( sodium bromide is equa ...

, and the marriage deteriorated, resulting in a number of separations, although they never divorced.

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director, and producer

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director, and producer Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

when she was 18 and Chaplin was 54. He never saw Oona again. Through his daughter, O'Neill had eight grandchildren whom he never met.

He also had distant relationships with his sons. Eugene O'Neill Jr., a Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

classicist, suffered from alcoholism and committed suicide in 1950 at the age of 40. Shane O'Neill became a heroin addict and moved into the family home in Bermuda, ''Spithead,'' with his new wife, where he supported himself by selling off the furnishings. He was disowned by his father before also committing suicide (by jumping out of a window) a number of years later. Oona ultimately inherited Spithead and the connected estate (subsequently known as the Chaplin Estate). In 1950 O'Neill joined The Lambs

The Lambs, Inc. (also known as The Lambs Club) is a New York City social club that nurtures those active in the arts, as well as those who are supporters of the arts, by providing activities and a clubhouse for its members. It is America's old ...

, the famed theater club.

Illness and death

After suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe

After suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe Parkinson's

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become more prevalen ...

-like tremor in his hands that made it impossible for him to write during the last 10 years of his life; he tried dictation but found himself unable to compose that way. While at Tao House, O'Neill had intended to write a collection of works he called "the Cycle" chronicling American life spanning from 1755 to 1932. Only two of the eleven plays O'Neill proposed, ''A Touch of the Poet

''A Touch of the Poet'' is a Play (theatre), play by Eugene O'Neill completed in 1942 but not performed until 1958, after his death.

It and its sequel, ''More Stately Mansions'', were intended to be part of a nine-play cycle entitled ''A Tale ...

'' and '' More Stately Mansions'', were completed. As his health worsened, O'Neill lost inspiration for the project and wrote three largely autobiographical plays, '' The Iceman Cometh'', '' Long Day's Journey into Night'', and '' A Moon for the Misbegotten'', which he completed in 1943, just before leaving Tao House and losing his ability to write. The book "''Love and Admiration and Respect": The O'Neill-Commins Correspondence''" includes an extended account written by Saxe Commins, O'Neill's publisher, in which he talks of "snatches of dialogue" between Carlotta and O'Neill over the disappearance of a group of manuscripts that O'Neill had brought with him from San Francisco. "When the table was cleared I learned the cause of the tension; the manuscripts were lost. They had disappeared mysteriously during the day and there was no clue to their whereabouts."

O'Neill died at the Sheraton Hotel (now

O'Neill died at the Sheraton Hotel (now Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. BU was founded in 1839 by a group of Boston Methodism, Methodists with its original campus in Newbury (town), Vermont, Newbur ...

's Kilachand Hall) on Bay State Road in Boston, on November 27, 1953, at age 65. As he was dying, he whispered: "I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room and died in a hotel room." He is interred in the Forest Hills Cemetery

Forest Hills Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery, greenspace, arboretum, and sculpture garden in the Forest Hills section of Jamaica Plain, a neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. The cemetery was established in 1848 as a pu ...

in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

's Jamaica Plain

Jamaica Plain is a Neighborhoods in Boston, neighborhood of in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Settled by Puritans seeking farmland to the south, it was originally part of Roxbury, Massachusetts, Roxbury. The community seceded from Roxbur ...

neighborhood.

In 1956, Carlotta arranged for his autobiographical play '' Long Day's Journey into Night'' to be published, although his written instructions had stipulated that it not be made public until 25 years after his death. It was produced on stage to tremendous critical acclaim and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957. It is widely considered his finest play. Other posthumously published works include ''A Touch of the Poet

''A Touch of the Poet'' is a Play (theatre), play by Eugene O'Neill completed in 1942 but not performed until 1958, after his death.

It and its sequel, ''More Stately Mansions'', were intended to be part of a nine-play cycle entitled ''A Tale ...

'' (1958) and '' More Stately Mansions'' (1967).

In 1967, the United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or simply the Postal Service, is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the federal governmen ...

honored O'Neill with a Prominent Americans series (1965–1978) $1 postage stamp.

In 2000, a team of researchers studying O'Neill's autopsy report concluded that he died of cerebellar cortical atrophy, a rare form of brain deterioration unrelated to either alcohol use or Parkinson's disease.

Legacy

InWarren Beatty

Henry Warren Beatty (né Beaty; born March 30, 1937) is an American actor and filmmaker. His career has spanned over six decades, and he has received an Academy Award and three Golden Globe Awards. He also received the Irving G. Thalberg Memor ...

's 1981 film '' Reds'', O'Neill is portrayed by Jack Nicholson

John Joseph Nicholson (born April 22, 1937) is an American retired actor and filmmaker. Nicholson is widely regarded as one of the greatest actors of the 20th century, often playing rebels fighting against the social structure. Over his five-de ...

, who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor

The Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It has been awarded since the 9th Academy Awards to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in ...

for his performance.

George C. White founded the Eugene O'Neill Theatre Center in Waterford, Connecticut in 1964.

Eugene O'Neill is a member of the American Theater Hall of Fame

The American Theater Hall of Fame was founded in 1972 in New York City. The first head of its executive committee was Earl Blackwell. In an announcement in 1972, he said that the new ''Theater Hall of Fame'' would be located in the Uris Theatre, ...

.

O'Neill is referenced by Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

in '' The Cup of Fury'' (1956), Dianne Wiest's character in '' Bullets Over Broadway'' (1994), by J.K. Simmons' character in '' Whiplash'' (2014), by Tony Stark in '' Avengers: Age of Ultron'' (2015), specifically ''Long Day's Journey into Night'', and ''Long Day's Journey into Night'' is also referenced by Patrick Wilson's character in '' Purple Violets'' (2007).

O'Neill is referred to in Moss Hart

Moss Hart (October 24, 1904 – December 20, 1961) was an American playwright, librettist, and theater director.

Early years

Hart was born in New York City, the son of Lillian (Solomon) and Barnett Hart, a cigar maker. He had a younger brother ...

's 1959 book '' Act One'', later a Broadway play.

Museums and collections

O'Neill's home in New London, Monte Cristo Cottage, was made a National Historic Landmark in 1971. His home in Danville, California, near San Francisco, was preserved as the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site in 1976.Connecticut College

Connecticut College (Conn) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in New London, Connecticut. Originally chartered as Thames College, it was founded in 1911 as the state's only women's colle ...

maintains the Louis Sheaffer Collection, consisting of material collected by the O'Neill biographer. The principal collection of O'Neill papers is at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

. The Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut, fosters the development of new plays under his name.

There is also a theatre in New York City named after him located at 230 West 49th Street in midtown-Manhattan. The Eugene O'Neill Theatre

The Eugene O'Neill Theatre, previously the Forrest Theatre and the Coronet Theatre, is a Broadway theater at 230 West 49th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York, U.S. The theater was designed by Her ...

has housed musicals and plays such as '' Yentl'', '' Annie'', '' Grease'', ''M. Butterfly

''M. Butterfly'' is a play by David Henry Hwang. The story, while entwined with that of the opera '' Madama Butterfly'', is based most directly on the relationship between French diplomat Bernard Boursicot and Shi Pei Pu, a Beijing opera sin ...

'', '' Spring Awakening'', and '' The Book of Mormon''.

Work

Full-length plays

* ''Bread and Butter'', 1914 * ''Servitude'', 1914 * ''The Personal Equation'', 1915 * ''Now I Ask You'', 1916 * '' Beyond the Horizon'', 1918 - Pulitzer Prize, 1920 * '' The Straw'', 1919 * '' Chris Christophersen'', 1919 * ''Gold'', 1920 * ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a Play (theatre), play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway theatre, Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According ...

'', 1920 - Pulitzer Prize, 1922

* '' The Emperor Jones'', 1920

* '' Diff'rent'', 1921

* ''The First Man'', 1922

* '' The Hairy Ape'', 1922

* ''The Fountain'', 1923

* ''Marco Millions'', 1923–25

* '' All God's Chillun Got Wings'', 1924

* ''Welded'', 1924

* '' Desire Under the Elms'', 1924

* '' Lazarus Laughed'', 1925–26

* '' The Great God Brown'', 1926

* '' Strange Interlude'', 1928 - Pulitzer Prize

* ''Dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos employed electromagnets for self-starting by using residual magnetic field left in the iron cores ...

'', 1929

* ''Mourning Becomes Electra

''Mourning Becomes Electra'' is a play cycle written by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. The play premiered on Broadway at the Guild Theatre on 26 October 1931 where it ran for 150 performances before closing in March 1932, starring Lee Ba ...

'', 1931

* '' Ah, Wilderness!'', 1933

* ''Days Without End'', 1933

* '' More Stately Mansions'', written 1937-1938, first performed 1967

* '' The Iceman Cometh'', written 1939, published 1940, first performed 1946

* '' Long Day's Journey into Night'', written 1941, first performed 1956; Pulitzer Prize 1957

* '' A Moon for the Misbegotten'', written 1941–1943, first performed 1947

* ''A Touch of the Poet

''A Touch of the Poet'' is a Play (theatre), play by Eugene O'Neill completed in 1942 but not performed until 1958, after his death.

It and its sequel, ''More Stately Mansions'', were intended to be part of a nine-play cycle entitled ''A Tale ...

'', completed in 1942, first performed 1958

One-act plays

The Glencairn Plays, all of which feature characters on the fictional ship ''Glencairn''—filmed together as '' The Long Voyage Home'': * ''Bound East for Cardiff'', 1916 * ''In the Zone

''In the Zone'' is the fourth studio album by American singer Britney Spears. It was released on November 15, 2003, by Jive Records. Spears began writing songs during her Dream Within a Dream Tour, not knowing the direction of the record. She ...

'', 1917

* ''The Long Voyage Home'', 1917

* ''Moon of the Caribbees'', 1918

Other one-act plays include:

* ''A Wife for a Life'', 1913

* ''The Web'', 1913

* ''Thirst'', 1913

* ''Recklessness'', 1913

* ''Warnings'', 1913

* ''Fog'', 1914

* ''Abortion'', 1914

* ''The Movie Man: A Comedy'', 1914

* ''The Sniper'', 1915

* ''Before Breakfast'', 1916

* ''Ile'', 1917

* ''The Rope'', 1918

* ''Shell Shock'', 1918

* ''The Dreamy Kid'', 1918

* ''Where the Cross Is Made'', 1918

* ''Exorcism'', 1919 (The play, set in 1912, is based on O'Neill's suicide attempt from an overdose of barbiturates in a Manhattan rooming house. After its premiere in 1920, O'Neill canceled the production and, it had been thought, destroyed all copies.)

* '' Hughie'', written 1941, first performed 1959

Other works

* ''Tomorrow'', 1917. A short-story published in ''The Seven Arts'', Vol. II, No. 8 in June 1917. * ''S.O.S.'', 1918. A short-story based on his 1913 one-act play ''Warnings''. * ''The Ancient Mariner'', 1923, a dramatic arrangement of Coleridge's poem. * ''The Last Will and Testament of an Extremely Distinguished Dog'', 1940. Written to comfort Carlotta as their "child" Blemie was approaching his death in December 1940. * ''Poems: 1912-1944'', published 1980. * ''The Calms of Capricorn'', unfinished play, published in 1983. * ''The Unfinished Plays'': Notes for ''The Visit of Malatesta'', ''The Last Conquest'' and ''Blind Alley Guy'', published in 1988.Wilkins, Frederick C. The Eugene O’Neill Review, vol. 13, no. 1, 1989, pp. 77–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29784342. Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.See also

* The Eugene O'Neill Award * List of residences of American writersReferences

Further reading

Editions of O'Neill

* * *Scholarly works

* *Bryan, George B. andWolfgang Mieder

Wolfgang Mieder (born 17 February 1944 in Nossen) is a retired professor of German and folklore who taught for 50 years at the University of Vermont, in Burlington, Vermont. He is a graduate of Olivet College (BA), the University of Michigan (MA ...

. 1995. ''The Proverbial Eugene O'Neill. An Index to Proverbs in the Works of Eugene Gladstone O'Neill''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

;Digital collections * *Works by Eugene O'Neill

a

Project Gutenberg Australia

* * *

Works by Eugene O'Neill

(public domain in Canada) ;Physical collections

Eugene O'Neill Collection.

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center, known as the Humanities Research Center until 1983, is an archive, library, and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe ...

.

* Eugene O'Neill Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

* Eugene O'Neill Papers Addition. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Carlotta O'Neill notebook of letters and photographs, 1927-1954

held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division,

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, is located at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza, in the Lincoln Center complex on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, New York City. Situated between the Metropolitan O ...

. The notebook contains handwritten transcriptions by Carlotta O'Neill of letters and inscriptions to her from her husband, Eugene O'Neill, and photographs, mostly portraits of Eugene and Carlotta O'Neill.

Harley Hammerman Collection on Eugene O'Neill

Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, Washington University in St. Louis.

Louis Sheaffer Collection of Eugene O'Neill

Connecticut College. ;Analysis and editorials

Haunted by Eugene O'Neill

��Article in ''BU Today'', September 29, 2009

Eugene O'Neill: the sailor, the sickness, the stage

from th

Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

;Seminal dissertations by scholars

* Eugene O’Neill e Lars Norén: “A Swedish-American Kinship” by Anna Airoldi * Postmodern Considerations of Nietzstchean Perspectivism in Selected Works of Eugene O'Neill by Eric Mathew Levin * The Pipe Dreams and Primitivism: Eugene O'Neill and the Rhetoric of Ethnicity by Donald P. Gagnon * The Discovery of the Self in Eugene O'Neill's ''The Emperor Jones'' and ''The Iceman Cometh'' and Joseph Conrad's ''Heart of Darkness'' and "To-morrow": A Comparative Study by Mohamed Amine Dekkiche * "Darker Brother" in Stage-Center: Eugene O'Neill's Quest for Racial Equity in Three Decades (1913-1939) of American Drama by Shahed Ahmed ;External entries * * * *

archive

;Other sources

Eugene O'Neill official website

Casa Genotta official website

American Experience - Eugene O'Neill: A Documentary Film on PBS

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Oneill, Eugene 1888 births 1953 deaths Eugene O'Neill O'Neill, Eugene American agnostics American Nobel laureates American people of Irish descent American writers of Irish descent Expressionist dramatists and playwrights Industrial Workers of the World members Irish-American history Laurence Olivier Award winners Modernist theatre Nobel laureates in Literature People from Danville, California People from Greenwich Village Writers from Manhattan Writers from New London, Connecticut People from Point Pleasant, New Jersey People from Provincetown, Massachusetts Writers from Ridgefield, Connecticut People with Parkinson's disease Princeton University alumni Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Tony Award winners Deaths from pneumonia in Massachusetts Members of The Lambs Club Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Members of the American Philosophical Society Writers of Irish descent Chaplin family