Ernest Bernard Malley (; 26 May 1897 – 25 March 1957) was an Irish republican and writer. After a sheltered upbringing, as a young medical student he witnessed and participated in the

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

of 1916, an event that changed his outlook fundamentally. O'Malley soon joined the

Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

before leaving home in spring 1918 to become an

IRA organiser and training officer during the

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

against

British rule in Ireland

British colonial rule in Ireland built upon the 12th-century Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland on behalf of the English king and eventually spanned several centuries that involved British control of parts, or the entirety, of the island of Irel ...

. In the later period of that conflict, he was appointed a divisional commander with the rank of general. Subsequently, O'Malley strongly opposed the

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

and became assistant chief of staff of the

Anti-Treaty IRA during the

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

of 1922–1923.

After being severely wounded in a gun battle with

Free State troops in November 1922, O'Malley was taken prisoner. He endured forty-one days on hunger strike in late 1923 and was the very last republican to be released from internment by the Free State authorities in July 1924. He then spent two years in Europe and North Africa to improve his health before returning to Ireland. Following an abortive attempt to resume his medical studies, O'Malley went to the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

to raise funds for a new nationalist newspaper and spent seven years wandering around the country and Mexico before beginning his writing and coming back to Ireland. In 1935 he married an American sculptor

Helen Hooker. He became well known in the arts and had a deep interest in folklore.

He wrote two memoirs, ''On Another Man's Wound'' and ''The Singing Flame'', and two histories, ''Raids and Rallies'' and ''Rising-Out: Seán Connolly of Longford'', covering his early life, the war of independence and the civil war period. These published works, in addition to his role as a senior leader on the losing side in the civil war, mark him as a primary source in the study of early twentieth-century Irish history and society. O'Malley also interviewed 450 people who participated in the war of independence and the civil war. Much of the evidence he gathered from them represents the activities and opinions of the ordinary soldier. By the time of his death in 1957, he had become a "deeply respected military hero".

Although he was elected, against his wishes, to

Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

in 1923 while in prison, O'Malley eschewed politics. As an Irish republican, he saw himself primarily as a soldier who had "fought and killed the enemies of our nation".

Early life

O'Malley was born in

Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Ireland. Developing around a 13th-century castle of the de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal point for the surrounding hinterland. Wi ...

,

County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

, on 26 May 1897.

[Richard English]

'O'Malley, Ernest Bernard ('Ernie')'

''Dictionary of Irish Biography'', October 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2022 His was a middle class

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

family in which he was the second of eleven children born to local man Luke Malley and his wife Marion (née Kearney) from Castlereagh,

County Roscommon

County Roscommon () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is part of the province of Connacht and the Northern and Western Region. It is the List of Irish counties by area, 11th largest Irish county by area and Li ...

. The family's storytelling governess also lived with them in Ellison Street. The house was opposite a

Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

(RIC) barracks. O'Malley noted the importance of the police and that officers would nod in courtesy when his father walked by. As a child, he often visited the barracks and was given a tour of it.

[O'Malley, ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 18] He also remembered RIC men dressed in suits leaving the town to keep peace at Orange parades in the North.

Although O'Malley heard of prominent political names like

Parnell and

Redmond at the dinner table, his parents never spoke of Ireland to him and his siblings. It was as if "nationality did not exist to disturb or worry normal life" in Castlebar, which he called a "shoneen town", meaning "a little John Bull town".

Still, he was able to learn a little bit of Irish. O'Malley's father was a solicitor's clerk with conservative

Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

politics: he supported the

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

. Priests dined in the Malley house and the family had privileged seats at Mass. The family spent the summer at

Clew Bay

Clew Bay (; ) is a large ocean bay on the Atlantic coast of County Mayo, Ireland. It is roughly rectangular and has more than a hundred small islands on its landward side; Ireland's best example of sunken drumlins. The larger Clare Island guar ...

, where O'Malley developed a lifelong love of the sea. He recounts meeting an old woman who, prophetically, spoke of fighting and trouble in store for him.

Dublin

The Malleys moved to

Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

in 1906 when Ernie was still a boy. The 1911 census lists them living at 7 Iona Drive,

Glasnevin

Glasnevin (, also known as ''Glas Naedhe'', meaning "stream of O'Naeidhe" after a local stream and an ancient chieftain) is a neighbourhood of Dublin, Ireland, situated on the River Tolka. While primarily residential, Glasnevin is also home to ...

, a northern suburb. His father obtained a post with the

Congested Districts Board and later became a senior civil servant. O'Malley considered that he received a reasonably good education at the O'Connell Christian Brothers School in North Richmond St, where he "rubbed shoulders with all classes and conditions". His nickname there was "Red Mick". He was later to win a scholarship to study medicine at

University College Dublin

University College Dublin (), commonly referred to as UCD, is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a collegiate university, member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 38,417 students, it is Ireland's largest ...

.

Joseph Devlin, the Belfast nationalist MP, visited O'Malley's school and made a very favourable impression on the boy.

However, he was less impressed by the visit of King

Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

to Dublin in July 1907, when he was aged ten, noting that he "didn't like the English" and spelt "king" with a small letter. O'Malley heard

James Larkin and

James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

speak during the great

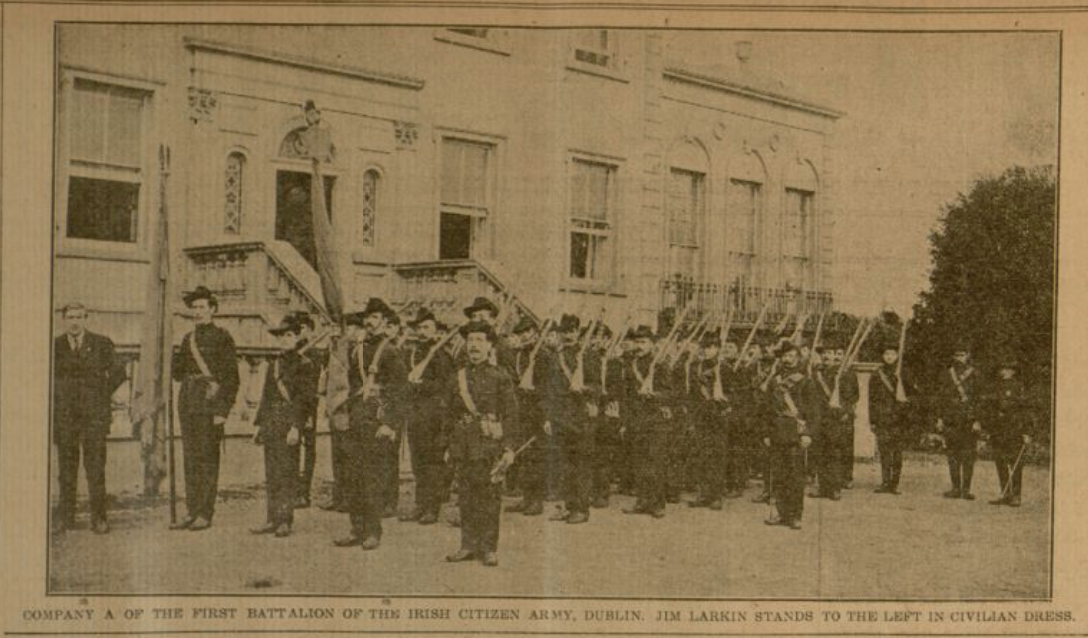

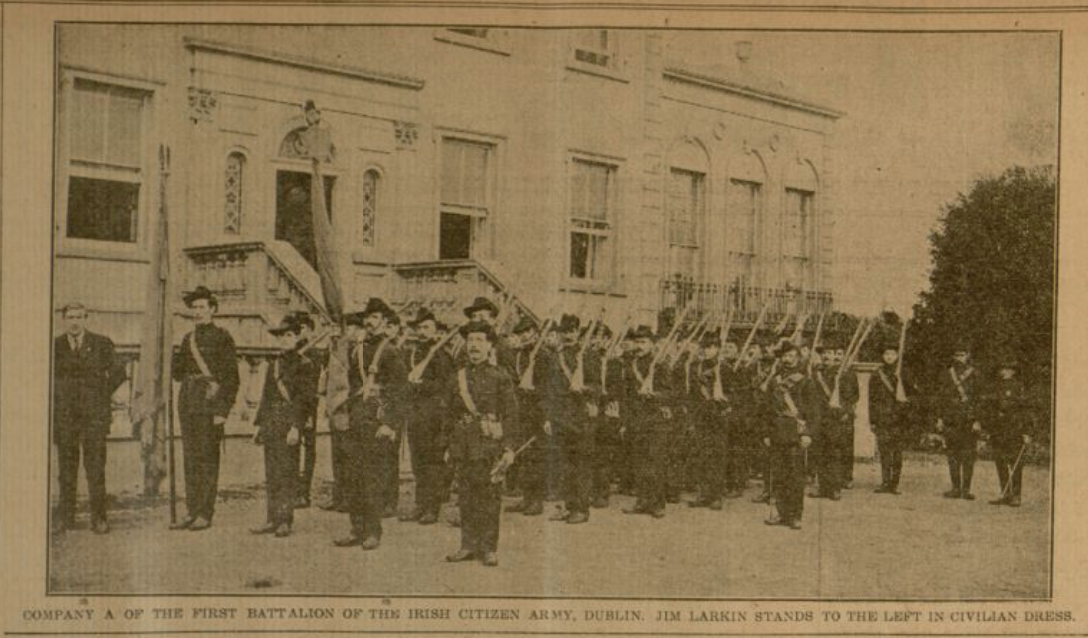

Dublin lock-out of 1913–1914. He witnessed heavy violence by the police and was in favour of the strikers' cause.

[O'Malley, ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 30] He also observed the

Irish Citizen Army drilling.

He heard of the

Howth gun-running

The Howth gun-running ( ) was the smuggling of 1,500 Mauser rifles to Howth harbour for the Irish Volunteers, an Irish nationalist paramilitary force, on 26 July 1914. The unloading of guns from a private yacht during daylight hours attracted a ...

incident that occurred in July 1914 and that three people had been killed in the aftermath.

His older brother, Frank, and next younger brother, Albert, joined the

Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the

British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

at the outbreak of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. O'Malley saw prime minister

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

in Dublin, where he had come to urge Irishmen to do their bit for the war effort. He was initially indifferent to the Irish Citizen Army and the

Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

, whom he had observed drilling in the mountains. At that time, O'Malley was planning to join the British Army, like his friends and brothers.

[O'Malley, ''On Another Man's Wound'', pp. 33–34] In August 1915, he saw the body of veteran Irish republican

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa lying in state and witnessed the funeral procession at

Glasnevin Cemetery.

Revolutionary career

Easter Rising and Irish Volunteers

O'Malley was in his first year of studying medicine at University College Dublin when the Easter Rising, which was soon to leave an "indelible mark" on him, convulsed the city in April 1916. He recalls that, on Easter Monday, he saw a new flag of green, white and orange on top of the General Post Office in

Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street) and later read the

Proclamation of the Republic at the base of

Nelson's Pillar. Of the leaders of the new “Provisional Government of the Irish Republic”, O'Malley had previously met

Tom Clarke and

Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh (; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, a signatory of the Proclama ...

.

O'Malley was almost persuaded by some anti-rising friends to join them in defending

Trinity College against the

rebels should they attempt to take it. O'Malley writes that he was offered the use of a rifle if he would return later and assist them. On his way home, he encountered an acquaintance who observed that O'Malley would be shooting fellow Irishmen, for whom he had no hatred, if he took that rifle. However, O'Malley recalls that his main feeling was one of mere annoyance at the inconvenience the fighting was causing. O'Malley kept a diary of what he saw during the rising, including looting.

After some thought, he decided that his sympathies lay with the nationalists: only Irish people had the right to settle Irish questions. Therefore, he and a school friend attacked British troops with a rifle. "My father was given one, a German

Mauser

Mauser, originally the Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik, was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols was produced beginning in the 1870s for the German armed forces. In the late 19th and ...

", he was told, "... by a soldier who brought it back from the front". This was O'Malley's first experience of using a weapon, a dangerous action that could have cost him his life. He and his friend made their escape before they were surrounded, but not before agreeing to meet up the following night. One commentator states that those responsible for O'Malley's pension claim in the 1930s "appear to have taken him at his word for the three days of peripatetic sniping activity" in the second part of Easter week.

[Marie Coleman (2018)]

'"There are thousands who will claim to have been 'out' during Easter Week: Recognising military service in the 1916 Easter Rising."'

''Irish Studies Review'', vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 12–13. Retrieved 1 June 2024 The resentment O'Malley felt at the shooting by firing squad of three of the signatories to the proclamation turned to rage at the execution in early May of

John MacBride, whom he knew from visits to the family home.

[O'Malley, ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 53]

Soon after the rising, O'Malley became deeply involved in

Irish republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

activism. In August 1916, he had been invited to join the Irish Volunteers, Dublin 4th Battalion, which operated south of the

River Liffey

The River Liffey (Irish language, Irish: ''An Life'', historically ''An Ruirthe(a)ch'') is a river in eastern Ireland that ultimately flows through the centre of Dublin to its mouth within Dublin Bay. Its major Tributary, tributaries include t ...

. However, because that battalion was quite a distance away, some time after Christmas 1916 he became a member of the 1st Battalion, F Company, because its base north of the Liffey was much nearer the family home. Later he was assigned to signals. From only twelve men in 1916, that company grew steadily during 1917 and 1918 under the captaincy of first Frank McCabe then Liam Archer.

O'Malley was unable to come and go freely from the family home, to which he was not given a key. That reality and his medical studies made it difficult to be on parade, and had to refuse training to become a non-commissioned officer. His three younger brothers helped keep his activities quiet, and older brother Frank, now a British army officer of whom he was very fond, knew nothing about his brother's nationalist activities. Despite passing his first university examinination in the autumn of 1916, O'Malley was spending less and less time at his studies and eventually lost his medical scholarship.

F Company engaged in drilling and parades from its secret drill hall at 25

Parnell Square; sometimes senior figures from the battalion staff were present. During a baton charge in

Westmoreland Street, O'Malley and his colleagues knocked over a policeman and ran off with his baton. In the second half of 1917, he joined the Gaelic League.

O'Malley paid £4, a considerable sum, for a rifle of his own. It was a

Lee-Enfield .303, which he hid in his bedroom. Later, in order to acquire a modern firearm, O'Malley donned his brother's British Army uniform and, armed with a loaded "bulldog .45" revolver, entered Dublin Castle. He held his nerve sufficiently to obtain a permit to purchase a

Smith & Wesson

Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. (S&W) is an American Firearms manufacturer, firearm manufacturer headquartered in Maryville, Tennessee, United States.

Smith & Wesson was founded by Horace Smith (inventor), Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson as the ...

.38 revolver and 200 rounds of ammunition.

Field organiser

O'Malley was finding it increasingly difficult to hide his activities from his parents, who queried the motives of the Irish Volunteers. Eventually, in early March 1918, he left both his studies and the family home and went on the run, working full-time for the Irish Volunteers, later called the IRA. It would be more than three years until he would see his family again.

At the time he became attached to General Headquarters (GHQ) Organisational Staff under

Michael Collins, there were not more than ten people who worked full-time for the Volunteers. While he was told which brigade area he was to work in and his best local contacts, O'Malley was given no detailed orders; instead, he was largely left to his own devices in organising rural brigades. This duty brought him to at least 18 brigade areas around Ireland. On one occasion he attended a meeting of the

Ulster Volunteer Force in Derry City for intelligence gathering but picked up nothing.

GHQ first dispatched O'Malley to assistant chief of staff,

Richard Mulcahy, at Dungannon, County Tyrone. He was appointed second lieutenant in charge of the

Coalisland

Coalisland () is a small town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, with a population of 5,682 in the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. Four miles from Lough Neagh, it was formerly a centre for coal mining.

History

Origins

In the late 1 ...

district.

In May 1918, Collins sent O'Malley, who had "less than two years of informal training with the Irish Volunteers" to

County Offaly

County Offaly (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is named after the Ancient Ireland, ancient Kingdom of Uí ...

. He was instructed "to hold brigade officer elections and develop a fighting unit in an area seventy-five miles south-west of Dublin". Collins told him to seek out some good men in that county that were "on the run". He arguably escaped capture or death when stopped by an RIC patrol in

Philipstown, in the same county, and narrowly avoided having to draw a concealed pistol.

From Athlone, where he was planning to seize the magazine fort, an order from Collins in July sent him to help organise brigades in north and south Roscommon on the border with Galway. The police sought to arrest him and he was twice fired on and wounded. He crossed again to Roscommon and went to ground in the mountains. Using field glasses, O'Malley spied on the

Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ov ...

,

Lord French, at

Rockingham House. This could have been hazardous in view of the strong British presence in nearby

Carrick-on-Shannon

Carrick-on-Shannon () is the county town of County Leitrim in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is the largest town in the county. A smaller part of the town located on the west bank of the River Shannon lies in County Roscommon and is home to th ...

. Night drilling continued in near silence behind village schoolhouses, but in a number of counties secret organising and planning for raids on RIC barracks to seize weaponry went ahead regardless of risk.

O'Malley took responsibility for organising over a dozen areas of the country from 1918 to 1921, even the remote Galway island of

Inisheer. In visiting many parts of Ireland, both by bicycle and on foot, O'Malley carried much of what he owned, some 60 lb. weight including his books and notebooks. Hence, he was obliged to be his own military base and commissariat. Nonetheless, he had very little money and was totally reliant on local people for his daily needs, including clothing.

Irish Republican Army

Although officially a "staff captain" (who reported only to GHQ in Dublin), O'Malley continued to act as an organiser and training officer for rural IRA brigades. This was an important duty: with minimal help from GHQ, he was to train recruits to become an effective local fighting force against a strong military opponent once the war against the British got under way in January 1919.

In mid-1919, O'Malley found himself in trouble with Collins for administering the new oath of allegiance to the Irish Republic to a company of IRA men in

Santry, County Dublin. Collins had shown him the wording of this oath but it had not yet been officially approved by GHQ. While Collins valued O'Malley’s work, the latter never overcame the negative initial impression he formed of Collins; nonetheless, his relationship with his superior was one of trust. Collins later sent O'Malley to London, where he once again dressed in British Army uniform to purchase a small number of revolvers and ammunition.

In February 1920,

Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish revolutionary, soldier, police commissioner, politician and fascist. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a promin ...

and O'Malley led an IRA attack on the RIC barracks in Ballytrain,

County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of Border Region, Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town ...

. They were successful in taking it, which was one of the first captures of an RIC barracks in the war. GHQ had developed this strategy in early 1920 to acquire desperately needed arms and ammunition.

In early May, O'Malley was assigned by Collins to the Tipperary area at the request of

Séumas Robinson and

Seán Treacy. He participated actively in attacks on three RIC barracks: Hollyford (11 May),

Drangan (4 June) and Rearcross (12 July). He had his hands burnt by a paraffin fire on the roof of Hollyford barracks; had the wind not changed direction at the very last second at Drangan, he would likely have been burnt alive; and he was wounded by shots fired upwards towards the roof by the policemen inside Rearcross barracks. These attacks made him well known as a man of action with leadership qualities.

[O'Malley, ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 332]

On 27 September, O'Malley and

Liam Lynch led the Cork No. 2 Brigade in an attack against the military barracks in

Mallow, County Cork

Mallow (; ) is a town in County Cork, Ireland, approximately thirty-five kilometres north of Cork (city), Cork City. Mallow is in a townland and Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish of the same name, in the Fermoy (barony), barony of Fermoy. ...

. This successful action saw the IRA capture large quantities of firearms and ammunition, partially burning the barracks in the process. In reprisal, soldiers went on a rampage in Mallow the next day.

In October, O'Malley served as a judge in the Republican Courts, recently established to undermine British rule.

Capture and escape

O'Malley was taken prisoner by

Auxiliaries in the home of local IRA commandant James O'Hanrahan at Inistioge,

County Kilkenny

County Kilkenny () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is named after the City status in Ir ...

, on the morning of 9 December 1920. He had been planning an attack on the Auxiliary barracks at

Woodstock House, an important base in the south-east of the county that he knew to be well guarded. O'Malley had been given an automatic Webley revolver; however, he was still unfamiliar with this new weapon and could not draw it in time. He had displayed an uncharacteristic lack of care regarding O'Hanrahan's house being a likely British raiding target. Much to O'Malley's disgust, also seized were notebooks containing the names of members of the 7th West Kilkenny Brigade, all of whom were subsequently detained.

On his arrest, he gave his name as "Bernard Stewart". O'Malley's arrest sheet records him as being from Roscommon and in possession of the loaded weapon and four maps. O'Malley endured a mixture of good treatment and violence from his various captors. This included being badly beaten during his interrogation at

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

where, as a self-confessed IRA volunteer, he was in severe danger of execution following recent high-profile attacks on British forces. By early January 1921, O'Malley was among the first to be imprisoned in

Kilmainham Gaol, which had been newly reopened for receipt of political prisoners.

He was held under the name of "Stuart", as recorded by the British. His fellow IRA man Simon Donnelly, who did not recognise O'Malley at first, recorded that this "Mr Stewart" looked different to before and was sporting a large moustache. Newspapers were forbidden there, but he was secretly given a copy of a newspaper article by someone else who knew his real identity. It referred to a recent raid on a flat in Dawson St, Dublin, in which many papers had been taken away and the female occupant of the flat arrested. That flat had been used by Michael Collins, some of whose papers were captured, while O'Malley had documents in a separate room.

The seizure of O'Malley's papers led to a new name of interest to the British. By late January, a letter from Dublin Castle to senior British military authorities referred to an IRA officer, a "notorious rebel" called "E. Malley", whom they were most anxious to arrest in connection with "many attacks on barracks".

The letter asked about tracing this man's older brother Frank, then an army officer in East Africa, to see if he could provide information on him.

The IRA leadership feared O'Malley could be executed, for he was one of a number of men regarded as "notorious murderers".

[Donnelly, p. 155] However, thanks to a plan devised by Collins he managed to escape from Kilmainham Gaol on 14 February 1921 along with colleagues

Frank Teeling and Donnelly. They were aided by two Welsh British Army soldier-guards who had republican sympathies and passed on a bolt-cutter that had been smuggled in.

Divisional commandant

In spring 1921 O'Malley chaired a stormy meeting near Mallow at which he advised senior Cork figures that GHQ had ordered the formation of the First Southern Division, in

Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

. At this gathering Liam Lynch was elected officer commanding of the IRA's largest fighting body. O'Malley was soon summoned to a meeting in Dublin with the President of the Irish Republic

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

, Collins and Mulcahy, where he was placed in command of the IRA's Second Southern Division, in Munster, ahead of more senior commanders in that province. With five brigades in Limerick, Kilkenny and Tipperary, it was the second-largest division in the IRA's new structure. As commandant-general of that division,

[O'Malley, ''The Singing Flame'', p. 296] O'Malley, not yet 24, now led more than 7,000 men.

He was to complain that his orders to brigade commandants for a coordinated attack on British forces in mid-May, as part of a wider IRA effort to prevent the execution of captured comrades, had not been carried out. However, on 19 June, his men captured three British Army officers. Citing the continuing execution of IRA prisoners in Cork, O'Malley had the men shot the next day after promising to send their valuables to their comrades.

O'Malley felt that the IRA was winning the war, so he was shocked when news reached him on 9 July that a truce would come into effect two days later. During the truce period in the second half of 1921, O'Malley considered that his state of preparedness for action in the county of Tipperary was getting better every day. O'Malley felt that while the British had control of the cities and towns, the IRA had free rein over the countryside.

The men under O'Malley's command initially thought the truce would only last for a few weeks, although it held as negotiations with the British gradually got underway. O'Malley was suspicious of the truce, but he used this time to work and strengthen his division, which saw visits from senior GHQ staff.

As munitions remained a problem, O'Malley went to London to purchase guns, where he met Collins during the peace negotiations. While he was there, members of his division had stolen British weapons. This led to a high-level IRA inquiry, as the action represented a breach of the truce and could have imperilled the negotiations. All in all, O'Malley felt that the IRA was still preparing for war.

Civil war and aftermath

Opposition to the treaty

O'Malley opposed the

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

on the grounds that any settlement falling short of an independent

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( or ) was a Revolutionary republic, revolutionary state that Irish Declaration of Independence, declared its independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdict ...

, particularly a settlement backed up by British threats of restarting hostilities, was unacceptable. Moreover, he expressed clear opposition to the

"Document No. 2", created by de Valera, which proposed "external association" with the British Empire as an alternative to the treaty. O'Malley offered his resignation as officer commanding the Second Southern Division. Mulcahy, now chief of staff, refused to accept it, telling him that he was "acting prematurely".

O'Malley's outright hostility to the treaty, which was ratified by

Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

on 7 January 1922, saw his division become the first to secede from GHQ. In mid-January, he informed Mulcahy in person of this decision. He is described as acting at that period as one of a number of "virtual warlords in their own areas". However, he was not alone in opposing the treaty: a small majority of GHQ staff and divisional commanders, and a larger majority of IRA volunteers, were against it. Sunday 26 February saw O'Malley lead an attack by the IRA South Tipperary brigade on the RIC barracks in the town of Clonmel, where he had his headquarters. A very large quantity of weapons, including an armoured car, and ammunition were taken. While this led the British government to ask the Provisional Government what measures they were taking to assert their control over Tipperary, the incident is not mentioned in O'Malley's account of what happened to barracks in his area after the treaty. Around this time O'Malley, who had refused to attend staff meetings at GHQ, ignored an order to attend a court martial in Dublin.

O'Malley was party to early meetings of what became known as the republican "acting military council". That body later established an anti-treaty headquarters staff in which O'Malley became director of organisation and a member of the executive; he was also secretary to the IRA Convention which went ahead on 26 March despite GHQ having banned it. The IRA was now officially split into pro- and anti-treaty camps.

On 14 April, O'Malley was one of the

Anti-Treaty IRA officers who occupied the

Four Courts

The Four Courts () is Ireland's most prominent courts building, located on Inns Quay in Dublin. The Four Courts is the principal seat of the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court and the Dublin Circuit Court. Until 2010 the build ...

in Dublin, an event that helped to widen the split even further prior to the start of the

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

. In late spring, he seized one of the first armoured cars handed over to local forces by the departing British and brought it from

Templemore, County Tipperary, to the Four Courts. O'Malley also repudiated any efforts at compromise with the pro-treaty side, made by some opponents of the treaty. He considered these as an attempt to create a wedge between the Four Courts garrison and the majority of republicans led by Lynch.

After the Four Courts Executive was established, O'Malley's deputy in operations was future

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

recipient

Seán MacBride. However, O'Malley relied primarily on his assistant

Todd Andrews. Even in late June O'Malley was planning an attack on

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

and sent Todd to Cavan to meet local IRA commandant Paddy Smith. On 26 June, he suggested and carried out the kidnapping of Free State assistant chief of staff,

J. J. "Ginger" O'Connell, and kept him prisoner in the Four Courts.

Outbreak of civil war

On 28 June 1922, government forces shelled the Four Courts. O'Malley was in the building when the

Records Office was blown up during the advance by

Free State troops on 30 June. The explosion cost him all the notes and manuals on training and tactics he had compiled and revised several times. Of that day he wrote in ''The Singing Flame'':

As we stood near the gate there was a loud shattering explosion … The munitions block and a portion of Headquarters block went up in flames and smoke … The yard was littered with chunks of masonry and smouldering records; pieces of white paper were gyrating in the upper air like seagulls. The explosion seemed to give an extra push to roaring orange flames which formed patterns across the sky. Fire was fascinating to watch; it had a spell like running water. Flame sang and conducted its own orchestra simultaneously. It can't be long now, I thought, until the real noise comes.

A national army report claimed that O'Malley later informed Free State general

Paddy O'Daly that the IRA had set off a mine inside the records office and that he was sorry more national army soldiers had not been injured.

O'Malley, who assumed operational command of the Four Courts occupation after garrison commander Paddy O'Brien was injured by shrapnel, was ordered by his senior IRA commanders – over his objections – to surrender to the Free State Army on the afternoon of 30 June. That evening he escaped from temporary captivity in the Jameson Distillery along with

Seán Lemass and two others. The next day he travelled via the

Wicklow Mountains

The Wicklow Mountains (, archaic: '' Cualu'') form the largest continuous upland area in Ireland. They occupy the whole centre of County Wicklow and stretch outside its borders into the counties of Dublin, Wexford and Carlow. Where the mountai ...

to

Blessington, then to

County Wexford

County Wexford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was ba ...

and finally to

County Carlow

County Carlow ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county located in the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region of Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Carlow is the List of Irish counties by area, second smallest and t ...

. This escape probably saved O'Malley's life, as four of the other senior Four Courts leaders

were later executed.

A force led by O’Malley captured

Enniscorthy

Enniscorthy () is the second-largest town in County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is located on the picturesque River Slaney and in close proximity to the Blackstairs Mountains and Ireland's longest beach, Curracloe.

The Plac ...

but this action cost the life of his comrade O'Brien and the IRA was forced to abandon much of

County Wexford

County Wexford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was ba ...

and south-east

Leinster

Leinster ( ; or ) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in the southeast of Ireland.

The modern province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige, which existed during Gaelic Ireland. Following the 12th-century ...

.

Assistant chief of staff

On 10 July 1922, O'Malley was made acting assistant chief of staff and was later appointed to the IRA army council.

He was second-in-command to Liam Lynch, who had been confirmed as IRA chief of staff when the split in republican ranks was healed on 27 June. He was also appointed as head of the Eastern and Northern Command, covering the provinces of

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

and Leinster.

[Ó Ruairc, ''Clare Interviews'', p. 10] O'Malley was disenchanted with being placed over areas he did not know well, instead of going to the west or south where his fighting experience would be put to much better use.

In September 1922, O'Malley pressed Lynch to implement

Liam Mellows

William Joseph Mellows (, 25 May 1892 – 8 December 1922) was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican and Sinn Féin politician. Born in England to an English father and Irish mother, he grew up in Ashton-under-Lyne before moving to Ireland, ...

' proposed 10-Point Programme for the IRA, which would have seen it adopt communist policies in an attempt to secure support from left-wing elements in Ireland.

However, even if O'Malley thought highly of Mellows, there is nothing in his civil war-focused writings to indicate that he supported the Communist thrust of Mellows' programme.

During an inspection of the North, O'Malley was in South Armagh in October. He joined

Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the I ...

(commander of the

IRA's 4th Northern Division) and

Pádraig Ó Cuinn (quartermaster-general) for a planned assault on Free State positions in

Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ) is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. The town is situated on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the north-east coast of Ireland, and is halfway between Dublin and Belfast, close to and south of the bor ...

. This operation was designed to rescue IRA men imprisoned after earlier attacks launched by Aiken but it turned out to be abortive.

O'Malley was forced to live a clandestine existence in Dublin city, where Madge Clifford of

Cumann na mBan was his secretary,

[Tim Horgan]

'Voices of the fighters from Independence and Civil War brought back to life'

''Irish Independent'', 2 July 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2025 and had to build up a new headquarters command staff. Moreover, effective military operations in the city were few and far between: O'Malley felt his men there lacked the spirit to carry out his orders and he considered himself a glorified clerk. From the start, he was frustrated at being cooped up and seeing no action. Todd Andrews recorded that O'Malley hated being shut up in Dublin and would have excelled as a field commander.

Lack of contact with Lynch was also a major problem: following a meeting of the IRA Executive on 15 July, none was held until 16–17 October.

At that meeting Lynch informed O'Malley, to his relief, that he would be moving IRA GHQ to Dublin and giving O'Malley command in the west; however, this did not happen. O'Malley also believed that Lynch's strategy of holding a defensive line in the south and locating GHQ in County Cork made no sense:

[O'Malley, ''The Singing Flame'', p. 153] a concerted attack on Dublin should have been an early priority. This lack of ambition, he argued, demoralised both the IRA and its supporters, and it allowed the "Staters" (the Free State Army) to build up their strength in preparation for a gradual take-over of areas of the country dominated by "Irregulars" (the IRA).

O'Malley expressed the view that, to win the war, guerrilla tactics were insufficient. Rather, the anti-treaty side needed to use more

conventional warfare

Conventional warfare is a form of warfare conducted by using conventional weapons and battlefield tactics between two or more sovereign state, states in open confrontation. The forces on each side are well-defined and fight by using weapons that ...

, with larger columns to drive the enemy out of towns and villages. He told Lynch that the destruction of communications, unless part of an immediate military operation, was folly, as it discouraged a fighting spirit. An uncoordinated struggle of scattered attrition, he wrote, was certain to lead to defeat.

In late October, O'Malley issued an order that the names of all enemy officers or soldiers who had ill-treated prisoners or been party of Free State “murder gangs” were to be circulated to IRA units with a shoot-on-sight instruction. Among three generals named was

Emmet Dalton, who, ironically, had been a schoolmate of O'Malley's.

Capture

On 4 November 1922, O'Malley was captured after a shoot-out with Free State soldiers at the family home of

Nell O'Rahilly Humphreys, 36 Ailesbury Road, in the

Donnybrook area of Dublin, which had been his headquarters for six weeks. He was severely wounded in the incident, being hit over nine times. A Free State soldier was also killed in the gunfight.

Anno O'Rahilly, who lived in the house, was accidentally shot by O'Malley during the raid but survived. He was kept in Portobello military hospital, where Free State army chief of staff

Seán MacMahon visited him in a private capacity. O'Malley was too ill to recognise the enemy general but learnt later that MacMahon had expressed a hope that O'Malley would not die.

Still severely affected by his wounds, O'Malley was transferred from Portobello to

Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison (), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed The Joy, is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Ray Murtagh.

History

Mountjoy was designed by Cap ...

hospital on 23 December 1922. As he made clear in ''The Singing Flame'', he was in grave danger of being one of the many executed for armed insurrection against the state and, additionally in his case, for killing a soldier. O'Malley believed that the authorities were waiting for him to recover sufficiently for an "elaborate trial" to take place, a scenario in which he would refuse to recognise the court. Charges were preferred against him in January 1923.

Another republican prisoner,

Peadar O'Donnell, recorded that it was only the intervention of O'Malley's doctors – who insisted that the prisoner was too ill even to be tried – that had saved him from a court martial and firing squad. O'Malley even wrote what he thought would be his final letter to Lynch.

However, no trial was held: there appeared to be official reservations about the reaction to shooting a man who would have to be carried to execution on a stretcher. This concern was likely heightened by inquiries about O'Malley made by prominent Americans and the publication in the Irish newspapers, ''The Times'' and the ''New York Times'', in January 1923, of reports about his severe condition.

By February 1923, despite letters to the contrary, he felt that the anti-treaty side had been beaten since before Christmas, in which regard he acknowledged his own failure.

O'Malley's most important external contact from prison was his friend the American-born Irish nationalist

Molly Childers, wife of

Erskine who was executed soon after O'Malley's arrest. The two corresponded on many topics, with Childers sending O'Malley all kinds of goods and food parcels.

Hunger strike

The civil war ended with the cessation of hostilities and dumping of arms in May 1923, but most IRA prisoners were not released until much later. On 13 October, O'Malley and many others in Mountjoy Prison went on

hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

for forty-one days, in protest at the continued detention of IRA prisoners (see

1923 Irish Hunger Strikes). After seven days O'Malley and the other senior officers or elected members were moved to Kilmainham Gaol. Against his will, he had been nominated as a

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

candidate for

Dublin North at the

1923 general election held on 27 August and was elected as a

TD. O'Malley "hated" being a member of the Dáil.

By 11 January 1924, O'Malley had been the last anti-treaty inmate moved from Kilmainham Gaol. He was transferred to St Bricin's military hospital, thence to Mountjoy Prison where at first he spent some time in the hospital wing. Then came a move to the Curragh army camp hospital in late winter before he joined the other anti-treaty prisoners in the huts of the Curragh camp. By mid-1924, the Free State government heard strong calls in parliament for the release of the final 600-odd anti-treaty prisoners, in the interests of restoring a more normal state of affairs. Further pressure came from the organisers of the

Tailteann Games, which were expected to be attended in early August by tens of thousands of overseas visitors.

Despite official reservations, the prisoners began to be set free. His period of internment complete, O'Malley was the very last anti-treaty prisoner to be released. He left the Curragh, along with

Seán Russell, on 17 July 1924, well over a year after the end of hostilities.

[Cormac O'Malley (2012). "Preface", in ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 5]

Secretary to IRA Executive

Upon his release, O'Malley went to his parents' home in Dublin and acted as he had before leaving home over six years previously. He also stayed with

Count Plunkett. Despite its defeat the IRA was still in existence. He became secretary to its executive and attended a meeting of that body on 10–11 August 1924 at which de Valera and almost all the IRA hierarchy were present. O'Malley was one of a sub-committee of five appointed to act as an army council to the executive. He also proposed a motion, passed unanimously, that IRA members must refuse to recognise courts in the Free State or

Six Counties for charges relating to actions committed during the war or to political activities since then. Further, a legal defence would only be permitted if the death penalty might be imposed. Yet his military career was over and he remained aloof from politics. O'Malley stayed with Sinn Féin and did not join

Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

in 1926, nor did he contest the

June 1927 general election.

During the civil war, three of O'Malley's younger brothers, Cecil, Paddy and Kevin, were arrested by Free State troops in July 1922. Another younger brother, Charlie, also anti-treaty, was killed on 4 July 1922 in Sackville Street during the

Battle of Dublin. In all, O'Malley suffered more than a dozen wounds from 1916 to 1923.

Subsequent life

Europe

O'Malley left Ireland in February 1925 and spent 18 months travelling in Europe and Morocco to improve his health. He used the alias 'Cecil Edward Smyth-Howard' and secured a British passport in that name. To finance his trip, he had raised some £300 in gifts and loans from sources in Ireland.

While abroad in the 1920s, O'Malley established connection with the

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

and

Catalan nationalists, becoming acquainted with

Francesc Macià, leader of the Catalan nationalist group

Estat Català. Seán MacBride, then living in Paris, was made aware that O'Malley was known to

French intelligence as a "chief military adviser to Colonel Macià", who was then in exile in Paris. O'Malley likewise appears to have liaised with

Basque nationalists

Basque nationalism ( ; ; ) is a form of nationalism that asserts that Basques, an ethnic group Indigenous peoples of Europe, indigenous to the western Pyrenees, are a nation and promotes the political unity of the Basques, today scattered bet ...

around this same period, as they were planning a rebellion in tandem with that of the Catalans.

[Kyle McCreanor]

'"Covert Irish Republican Assistance to Basque and Catalan Nationalists, 1925–6"'

''History Ireland'', vol. 33, issue 1 (January/February 2025). Retrieved 18 January 2025. O'Malley was one of two Irish republicans, the other being

Ambrose Victor Martin, to have cooperated with the Basque and Catalan nationalists resident in Paris, then exiled from the Spanish dictatorship of

Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquis of Estella, Grandee, GE (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a Spanish dictator and military officer who ruled as prime minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during the last years of the Resto ...

. Peadar O'Donnell stated that the IRA Army Council had given the go-ahead for O'Malley to speak to the Catalan separatists.

The following excerpt from a letter from O'Malley to Harriet Monroe, dated 10 January 1935, provides an autobiographical summary of the years 1925–1926:

I went to Catalonia to help the Catalan movement for independence; I studied their folklore and cultural institutions. I learned to walk again in the Pyrénées

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto.

F ...

. I became a good mountain climber, covered the frontier from San Sebastian to Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

, lived in the Basque country. I walked through a part of Spain, southern and South East France and most of Italy. I did some mediaeval history at Grenoble

Grenoble ( ; ; or ; or ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of the Isère Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Regions of France, region ...

. I walked through Italy slowly, worked at archeology in Sicily and lived in Rome and Florence for a time. I walked through Germany to Holland and through Belgium and then to North Africa. After some years I returned to the National University to again take up medicine but I did not get my exams. The years abroad taught me to use my eyes in a new way.

North America

O'Malley returned to University College Dublin to continue his medical studies in October 1926, but these did not progress well. He was heavily involved in the university hill-walking club and its literary and historical societies; along with literary friends, he founded the college Dramatic Society in spring 1928.

He left Ireland again in October 1928 without graduating. For eight months in 1928 and 1929, he and Frank Aiken toured the east and west coasts of the USA on behalf of de Valera's plan to raise funds for the establishment of the new, independent pro-republican newspaper, ''

The Irish Press

''The Irish Press'' (irish language, Irish: ''Scéala Éireann'') was an Ireland, Irish national daily newspaper published by Irish Press plc between 5 September 1931 and 25 May 1995.

History Foundation

The paper's first issue was published o ...

''. O'Malley considered a newspaper that would articulate the anti-treaty position an important development. That fund-raising effort was successful: the newspaper was published and flourished for many years.

O'Malley spent the next few years based in New Mexico, Mexico and New York. In September 1929, he arrived in

Taos, New Mexico

Taos () is a town in Taos County, New Mexico, Taos County, in the north-central region of New Mexico in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Initially founded in 1615, it was intermittently occupied until its formal establishment in 1795 by Santa Fe ...

. He lived among the literary and artistic community there and close to the Native American pueblo of Taos. He began work on his account of his military experiences that would later become ''On Another Man's Wound''. At that time he fell in with

Mabel Dodge Luhan,

Dorothy Brett and Irish poet

Ella Young. In May 1930, he moved to Santa Fe, where he gave lectures on Irish culture, history and literature. A figure of particular interest was

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

, whose

''Ulysses'' was to influence the presentation of ''On Another Man's Wound''.

In 1931, he travelled to Mexico for eight months observing its culture and artists. However, he failed to secure employment there as he had hoped. His US visa having expired, he reputedly swam across the Rio Grande to return to Santa Fe. From late 1931 to June 1932, O'Malley worked in Taos as a tutor to the children of Helen Golden, widow of leading New York Irish nationalist Peter Golden; when she was hospitalised in early 1932, O'Malley looked after the children. During this period he became good friends with photographer Paul Strand. In June 1932, he travelled to New York, where in 1933 he met 28 year old

Helen Hooker, a wealthy young sculptor and gifted tennis player, whom he was later to marry.

Return to Ireland

In 1934, O'Malley was granted a wound and war pension of approximately £330 a year by the Fianna Fáil government for his service in the War of Independence. Academic Marie Coleman believes that he was treated generously – compared to others – despite not having become a member of the Irish Volunteers until several months after the Easter Rising.

In June of that year, it was noted in the Dáil that he was rumoured to be coming back into public life as chief of staff of the Volunteer Force created by the government in April. While remaining out of political life, he later convened a meeting of anti-Franco Irish republicans when most people in Ireland supported

Franco in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.

Now possessed of a steady income, he married Hooker in London on 27 September 1935,

[Bridget Hourican]

'Hooker, Helen O'Malley'

''Dictionary of Irish Biography'', October 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2022 before he returned to Ireland to resume his medical studies. The O'Malleys had three children, all born in Dublin: Cathal (a son, 1936), Etain (a daughter, 1940) and

Cormac (a son, 1942). The family divided its time between Dublin and Burrishoole, Newport, County Mayo. Hooker and O'Malley devoted themselves to the arts: she was involved in sculpture, photography and theatre, while he pursued a career in history and the arts as a writer.

Jack Butler Yeats was amongst his friends and the art collection O'Malley assembled was later to sell for over €5.4 million. Not long after his return to Ireland O'Malley became a member of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland to further his interest in folklore.

[Emily Hourican]

'"Life did change after my mother left and after she took my brother and sister" - Ernie O'Malley’s son Cormac'

''Irish Independent'', 15 December 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2025 He remained in neutral Ireland during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and offered his services to his local defence force in Mayo but was not accepted. This was likely on account of his poor health: he had also farmed in Burrishole from 1940 to 1944 and was worn out. O'Malley got to know the members of his family again, many of whom had distinguished careers during and after the war.

[Peter McDermott]

'A family at war'

''The Irish Echo'', 16 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2025

In September 1944, the family moved to Clonskeagh, Dublin, although Helen was often absent. By the end of the war years the O'Malleys' marriage had begun to fail.

[ In summer 1945, Helen O'Malley went to America for six months to see her family and thereafter began to spend more time away from her husband and children. This period included a year in London in 1946–1947. After 1948 she returned to the United States. In 1950, Helen took her two elder children out of Coláiste na Rinne, an Irish-language boarding school at Ring, County Waterford. She flew them to the States to live with her. The youngest child was not at school and thus stayed with his father. This incident was referred to as a "kidnapping". Helen divorced her husband in 1952.][

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, he carried out and compiled a written record of hundreds of interviews with veterans of the war against the British and the fratricidal struggle that followed it. Planned since the late 1930s, it began to take shape in 1945 when O'Malley consulted Florrie O'Donoghue about the latter's idea of collecting Tan War memories. O'Malley's work, written in a colloquial style in notebooks,]John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), better known as John Ford, was an American film director and producer. He is regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers during the Golden Age of Hollywood, and w ...

on the set of '' The Quiet Man'' and the two became firm friends.

Illness and death

Throughout his life, O'Malley endured considerable ill-health from the wounds and hardship he had suffered during his revolutionary days. His main weakness, however, was a heart condition that started in childhood. His brother Kevin, a heart specialist, took care of him in later years, especially after O'Malley suffered a serious heart attack in spring 1953. In August 1954, O'Malley moved with his son Cormac to a flat in Dublin to have easier access to a hospital and be closer to brother Kevin.[ During the summers of 1954 to 1956 O'Malley and his son spent time on the ]Aran Islands

The Aran Islands ( ; , ) or The Arans ( ) are a group of three islands at the mouth of Galway Bay, off the west coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, with a total area around . They constitute the historic barony (Ireland), barony of Aran in ...

, where the ailing republican gathered local folklore and information on fishing.

Ernie O'Malley died at 9.20 a.m. on Monday 25 March 1957 at his sister Kaye's home in Howth. Contrary to his wishes, he was given a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

by the newly elected Fianna Fáil government. It was attended by many of the deceased's comrades from all over Ireland, including President Seán T. O'Kelly, de Valera, Lemass, Aiken and Dan Breen. While O'Malley's ex-wife, children and brothers looked on, Sean Moylan delivered the graveside oration: "There wasn't a corner of Ireland where a soldier of Ireland's revolutionary period survived that the name of Commandant-General Ernie O'Malley would not evoke proud memories, not a place where patriotism was honoured that would not sorrow at his death. He was fortunate, Ireland was fortunate in his being born into a period of Irish history where his special gifts, his soldierly qualities could be used to the greatest effect ... The Ireland of his generation was not lacking in men of high purpose, deep sincerity and courage ... among them, Ernie O'Malley had pride of place".

Legacy

O'Malley remains an important figure in a "fractious period" of 20th-century Irish history. Roy Foster observed: "What remains striking about O’Malley’s legacy is not only his creation of one of the most remarkable memoirs in Irish literary history, but also the story of the journey of a deeply original and powerful intelligence, coping with the fallout of an extraordinary youth and a saddened middle age". O'Malley firmly believed that Ireland, having been dominated by an occupying power for so long, deserved to rule itself. Achieving that aim was the sole, almost overwhelming, focus of his early adult years. He contributed significantly to making IRA volunteers, often poorly armed, into a formidable guerrilla force. Lemass considered him an exceptional military field commander. However, he decried O'Malley's utility as a strategist at HQ albeit with the civil war already lost to the republicans by then. Tom Barry, who was passed over for the divisional command given to O'Malley, felt that the latter paid too much heed to the military manual.

Todd Andrews stated that O'Malley had "taken part in more attacks on British soldiers, Black and Tans and RIC than any other IRA men in Ireland"; yet while admired, he was not generally liked. O'Malley's good friend Tony Woods, who had been in the Four Courts, disapproved of ''The Singing Flame'' (which he incorrectly attributed to Frances-Mary Blake) and considered O'Malley "only a third-rate general". Maire Comerford believed that the civil war would not have been lost by the anti-treaty side if all IRA men had been like O'Malley. Simon Donnelly considered him "Without doubt one of the bravest soldiers who ever fought for Irish independence".Ken Loach

Kenneth Charles Loach (born 17 June 1936) is a retiredhttps://variety.com/2024/film/global/ken-loach-retirement-the-old-oak-jonathan-glazer-oscars-speech-1235956589/ English filmmaker. His socially critical directing style and socialist views ar ...

2006 film ''The Wind that Shakes the Barley'' and the character of Damien Donovan is based loosely on O'Malley. A sculpture of Manannán mac Lir, donated in his memory by Helen Hooker, stands in the Mall in Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Ireland. Developing around a 13th-century castle of the de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal point for the surrounding hinterland. Wi ...

, County Mayo. A 2007 proposal to rename a road in Castlebar in O'Malley's honour was strongly supported by local residents but rejected by town councillors. Despite O'Malley's appreciation of the arts, Todd Andrews did not consider him an intellectual.

A documentary film on O'Malley's life, ''On Another Man's Wound: Scéal Ernie O'Malley'' ("Ernie O'Malley's Story"), was made for TG4 by Jerry O'Callaghan in 2008. ''A Call to Arts'', a documentary about the artistic journey of Helen Hooker and Ernie O'Malley, was produced by Cormac O'Malley and directed by Chris Kepple in 2020. It was shown on Connecticut Public Television (2020) and RTÉ (2021).

There is a small museum, housing some of O'Malley's stamp and coin collection, in an Irish pub named in his honour in the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City.

Works

* ''On Another Man's Wound'' (London, Rich & Cowan, 1936)

* ''Army Without Banners: Adventures of an Irish Volunteer'' (Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1937)

* ''The Singing Flame'' (Dublin, Anvil Books, 1978)

* ''Raids and Rallies'' (Dublin, Anvil Books, 1982)

* ''Rising-Out: Seán Connolly of Longford'' (Dublin, UCD Press, 2007)

* ''Broken Landscapes: Selected Letters of Ernie O'Malley 1924–1957'' (Dublin, Lilliput Press, 2011)

* ''"No Surrender Here!" The Civil War Papers of Ernie O'Malley 1922–1924'' (Dublin, Lilliput Press, 2007)

In 1928, in a letter to fellow republican Sheila Humphreys, O'Malley explained his attitude to writing:I have the bad and disagreeable habit of writing the truth as I see it, and not as other people (including yourself) realise it, in which we are a race of spiritualised idealists with a world idea of freedom, having nothing to learn for we have made no mistakes.

O'Malley's most celebrated writings are ''On Another Man's Wound'', a memoir of the Irish War of Independence, and its sequel, ''The Singing Flame'', a continuing memoir of his involvement in the Irish Civil War. These two volumes were written during O'Malley's time in New York, New Mexico and Mexico between 1929 and 1932.[In ''On Another Man's Wound'' (London, 1936), there are six rows of asterisks and c. 1.5" of blank space at the bottom of p. 246, with the note: ' ix pages have been deleted by the publishers. In the unabridged American version of the book, published in 1937 as ''Army Without Banners: Adventures of an Irish Volunteer'', the missing text is published from the top of p. 288 to the middle of p. 295, where the narrative continues with: “Two girls walked..." In the latest edition of ''On Another Man's Wound'' (2013), the missing text can be seen from near the bottom of p. 312 to low down on p. 320. See also Cormac O'Malley (2012). "Preface", in ''On Another Man's Wound'', p. 6.] An unabridged version was published in America a year later under the title ''Army Without Banners: Adventures of an Irish Volunteer''. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' described it as "a stirring and beautiful account of a deeply felt experience", while the '' New York Herald Tribune'' called it "a tale of heroic adventure told without rancor or rhetoric".The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It was launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is Ireland's leading n ...

'' in 1996, the writer John McGahern described ''On Another Man's Wound'' as "the one classic work to have emerged directly from the violence that led to independence", adding that it "deserves a permanent and honoured place in our literature".

''On Another Man’s Wound'' was published in Germany in 1938, 1941 and 1943 as ''Rebellen in Irland: Erlebnisse eines irischen Freiheitskämpfers'' (Rebels in Ireland: Experiences of an Irish Freedom Fighter). While the book was acclaimed internationally, not everyone was thrilled with it. A former IRA colleague, Joseph O'Doherty from Donegal, sued O'Malley for libel. This led to a court case in 1937, which O'Malley lost. It cost him £400 in damages, a substantial sum well over his annual pension.

Perhaps on account of its more controversial theme, ''The Singing Flame'' was not published until 1978, over twenty years after O'Malley's death.[O'Malley, ''Clare Interviews'', p. 11]

His official military and personal papers on the civil war were published in 2007, under the title, ''"No Surrender Here!" The Civil War Papers of Ernie O'Malley, 1922–1924''. His personal letters were published in 2011 as ''Broken Landscapes: Selected Letters of Ernie O'Malley, 1924–1957''. In 2012, a series entitled ''The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O'Malley's Interviews'' was initiated and has the interviews he made in Kerry, Galway, Mayo, Clare, Cork and with the Northern Divisions.

O'Malley wrote and published some poetry in ''Poetry'' magazine (Chicago) in 1935 and 1936, and in the ''Dubliner Magazine'' in 1935. From 1946 to 1948, he also contributed, as books editor, to the literary and cultural magazine, '' The Bell'', edited by his old comrade Peadar O'Donnell now the editor of the periodical. In late 1946, O'Malley explained the recent revolutionary conflict in Ireland and the context of Irish neutrality during WWII for a French audience. O'Malley also gathered ballads and stories from the revolutionary period; and during World War II, he noted down over 300 traditionary folktales from his native area near Clew Bay in Mayo.

New York University Libraries

Notes

References

Sources

*

*

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Ernie O'Malley: Soldier, Writer, Artist – the official website maintained by his son, Cormac O'Malley

(ernieomalley.com)

Papers of Ernie O'Malley, UCD ArchivesErnie O'Malley Papers

at Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University

Ernie's Journey (56 podcasts) by Cormac O'MalleyBohemian Revolutionary: Ernie O'Malley (Part 1) – first podcast on O'Malley, including contributions by Cormac O'MalleyFrom the Four Courts to the Quiet Man: Ernie O'Malley (Part 2) – second podcast on O'Malley, including contributions by Cormac O'MalleyOn Another Man's Wound, Scéal Ernie O'Malley (TG4, 2008)Ernie O'Malley: A Life, Ted Smyth interviewing Cormac O' Malley

{{DEFAULTSORT:Omalley, Ernie

1897 births

1957 deaths

Early Sinn Féin TDs

Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members

Irish Republican Army (1922–1969) members

Irish hunger strikers

Irish male non-fiction writers

Members of the 4th Dáil

Military personnel from County Mayo

People from Castlebar

People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side)

Politicians from County Mayo

20th-century Irish non-fiction writers

Writers from County Mayo

His older brother, Frank, and next younger brother, Albert, joined the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the

His older brother, Frank, and next younger brother, Albert, joined the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the  O'Malley was almost persuaded by some anti-rising friends to join them in defending Trinity College against the rebels should they attempt to take it. O'Malley writes that he was offered the use of a rifle if he would return later and assist them. On his way home, he encountered an acquaintance who observed that O'Malley would be shooting fellow Irishmen, for whom he had no hatred, if he took that rifle. However, O'Malley recalls that his main feeling was one of mere annoyance at the inconvenience the fighting was causing. O'Malley kept a diary of what he saw during the rising, including looting.

After some thought, he decided that his sympathies lay with the nationalists: only Irish people had the right to settle Irish questions. Therefore, he and a school friend attacked British troops with a rifle. "My father was given one, a German

O'Malley was almost persuaded by some anti-rising friends to join them in defending Trinity College against the rebels should they attempt to take it. O'Malley writes that he was offered the use of a rifle if he would return later and assist them. On his way home, he encountered an acquaintance who observed that O'Malley would be shooting fellow Irishmen, for whom he had no hatred, if he took that rifle. However, O'Malley recalls that his main feeling was one of mere annoyance at the inconvenience the fighting was causing. O'Malley kept a diary of what he saw during the rising, including looting.

After some thought, he decided that his sympathies lay with the nationalists: only Irish people had the right to settle Irish questions. Therefore, he and a school friend attacked British troops with a rifle. "My father was given one, a German  On 28 June 1922, government forces shelled the Four Courts. O'Malley was in the building when the Records Office was blown up during the advance by Free State troops on 30 June. The explosion cost him all the notes and manuals on training and tactics he had compiled and revised several times. Of that day he wrote in ''The Singing Flame'':

On 28 June 1922, government forces shelled the Four Courts. O'Malley was in the building when the Records Office was blown up during the advance by Free State troops on 30 June. The explosion cost him all the notes and manuals on training and tactics he had compiled and revised several times. Of that day he wrote in ''The Singing Flame'':

O'Malley expressed the view that, to win the war, guerrilla tactics were insufficient. Rather, the anti-treaty side needed to use more

O'Malley expressed the view that, to win the war, guerrilla tactics were insufficient. Rather, the anti-treaty side needed to use more