Elizabeth Stuart, Queen Of Bohemia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 1596 – 13 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. The couple's selection for the crown by the nobles of

p. 157

"ELIZABETH STUART.-Calderwood, after referring to a tumult in Edinburgh, says, that shortly before these events, the Queen (of James VI.) was delivered of a daughter in the palace of Dunfermline, on the 19th of August 1596. King James rode to the bedside from Callendar, where he was attending the wedding of the

Her arrival in Heidelberg was seen as "the crowning achievement of a policy which tried to give the Palatinate a central place in international politics" and was long anticipated and welcomed. Elizabeth's new husband transformed his seat at Heidelberg Castle, creating between 1610 and 1613 the ''Englischer Bau'' (i.e., English Building) for her, a monkey-house, a

Her arrival in Heidelberg was seen as "the crowning achievement of a policy which tried to give the Palatinate a central place in international politics" and was long anticipated and welcomed. Elizabeth's new husband transformed his seat at Heidelberg Castle, creating between 1610 and 1613 the ''Englischer Bau'' (i.e., English Building) for her, a monkey-house, a  Although Elizabeth and Frederick were considered to be genuinely in love and remained a romantic couple throughout the course of their marriage, problems already had begun to arise. Before the couple had left England, King James had made Frederick promise that Elizabeth "would take precedence over his mother ... and always be treated as if she were a Queen". This at times made life in the Palatinate uncomfortable for Elizabeth, for Frederick's mother Louise Juliana had "not expected to be demoted in favour of her young daughter-in-law" and, as such, their relationship was never more than civil.

Elizabeth gave birth to three children in Heidelberg: Frederick Henry, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate (sometimes called Henry Frederick) was born in 1614,

Although Elizabeth and Frederick were considered to be genuinely in love and remained a romantic couple throughout the course of their marriage, problems already had begun to arise. Before the couple had left England, King James had made Frederick promise that Elizabeth "would take precedence over his mother ... and always be treated as if she were a Queen". This at times made life in the Palatinate uncomfortable for Elizabeth, for Frederick's mother Louise Juliana had "not expected to be demoted in favour of her young daughter-in-law" and, as such, their relationship was never more than civil.

Elizabeth gave birth to three children in Heidelberg: Frederick Henry, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate (sometimes called Henry Frederick) was born in 1614,

File:Gerrit van Honthorst - Triumph of the Winter Queen.jpg, ''Triumph of the Winter Queen: Allegory of the Just'', 1636, by

Elizabeth filled her time with copious letter writing and making marriage matches for her children. Between Frederick's death in 1632 and her own 30 years later, she witnessed the deaths of four more of her ten surviving children: Gustavus in 1641,

In 1660, the Stuarts were

In 1660, the Stuarts were

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

was part of the political and religious turmoil that set off the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. Since her husband's reign in Bohemia lasted over only one winter, she is called "The Winter Queen" (, ).

Princess Elizabeth was the only surviving daughter of James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 M ...

, King of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, and his queen, Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

; she was the elder sister of Charles I. Born in Scotland, she was named in honour of her father's predecessor and cousin in England, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

. During Elizabeth Stuart's childhood, unbeknownst to her, part of the failed Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

was a scheme to replace her father with her on the throne, and forcibly raise her as a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

.

Her father later arranged for her marriage to the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

Frederick V, a senior prince of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. They were married in the Chapel Royal in the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, ...

, and then left for his lands in Germany. Their marriage proved successful, but after they left Bohemia, they spent years in exile in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

, while the Thirty Years' War continued. In her widowhood, she eventually returned to England at the end of her own life during the Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

of her nephew and is buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

.

With the demise in 1714 of Elizabeth's great-niece, Anne, Queen of Great Britain

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 8 March 1702, and List of British monarchs, Queen of Great Britain and Irel ...

, the last Stuart monarch, the British throne passed to her grandson (by her daughter Sophia of Hanover

Sophia (born Princess Sophia of the Palatinate; – ) was Electress of Hanover from 19 December 1692 until 23 January 1698 as the consort of Prince-Elector Ernest Augustus. She was later the heiress presumptive to the thrones of England and ...

) as George I, initiating the rule of the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover ( ) is a European royal house with roots tracing back to the 17th century. Its members, known as Hanoverians, ruled Hanover, Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Empire at various times during the 17th to 20th centurie ...

.

Early life

Elizabeth was born at Dunfermline Palace,Fife

Fife ( , ; ; ) is a council areas of Scotland, council area and lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area in Scotland. A peninsula, it is bordered by the Firth of Tay to the north, the North Sea to the east, the Firth of Forth to the s ...

, on 19 August 1596 at 2 o'clock in the morning.M. Barbieri, ''Descriptive and Historical Gazetteer of the Counties of Fife, Kinross, and Clackmannan'' (1857)p. 157

"ELIZABETH STUART.-Calderwood, after referring to a tumult in Edinburgh, says, that shortly before these events, the Queen (of James VI.) was delivered of a daughter in the palace of Dunfermline, on the 19th of August 1596. King James rode to the bedside from Callendar, where he was attending the wedding of the

Earl of Orkney

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally Scandinavian Scotland, founded by Norse invaders, the status ...

. At the time of her birth, her father was King of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

, but not yet King of England. Named in honour of Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, her godmother, the young Elizabeth was christened on 28 November 1596 in the Chapel Royal at Holyroodhouse, and was then proclaimed by the heralds as "Lady Elizabeth". During her early life in Scotland, Elizabeth was brought up at Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland in the 15th and 16th ce ...

, where she was placed in the care of Lord Livingstone and his wife, Eleanor Hay. A couple of years later the king's second daughter, Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, was placed in their care as well. Elizabeth "did not pay particular attention to this younger sister", as even at this young age her affections were with her brother, Henry.

Move to England

When Queen Elizabeth I of England died in 1603, Elizabeth Stuart's father, James, succeeded as King of England and Ireland. The Countess of Kildare was appointed the princess's governess. Along with her elder brother, Henry, Elizabeth made the journey southward to England with her mother "in a triumphal progress of perpetual entertainment". On her father's birthday, 19 June, Elizabeth danced at Worksop Manor with Robert Cecil's son. Elizabeth remained at court for a few weeks, but "there is no evidence that she was present at her parents' coronation" on 25 July 1603. It seems likely that by this time the royal children already had been removed to Oatlands, an old Tudor hunting lodge near Weybridge. There was plague in London, and Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth were moved toWinchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

. Her mother, Anne of Denmark, produced a masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

to welcome them. On 19 October 1603 "an order was issued under the privy seal announcing that the King had thought fit to commit the keeping and education of the Lady Elizabeth to the Lord Harrington and his wife".

Under the care of Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

and Lady Harington at Coombe Abbey, Elizabeth met Anne Dudley, with whom she was to strike up a lifelong friendship. On 3 April 1604, Princess Elizabeth and her ladies rode from Coombe Abbey to Coventry

Coventry ( or rarely ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands county, in England, on the River Sherbourne. Coventry had been a large settlement for centurie ...

. The Mayor and Aldermen met her at " Jabet's Ash on Stoke-green". She heard a sermon in St Michael's Church and dined in St Mary's Hall.

Gunpowder Plot

Part of the intent of theGunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

of 1605 was to assassinate Elizabeth's father King James and the Protestant aristocracy, kidnap the nine-year-old Elizabeth from Coombe Abbey, and place her on the throne of England – and presumably the thrones of Ireland and Scotland – as a Catholic monarch. The conspirators chose Elizabeth after considering the other available options. Prince Henry, it was believed, would perish alongside his father. Charles was seen as too feeble (having only just learnt to walk) and Mary too young. Elizabeth, on the other hand, had already attended formal functions, and the conspirators knew that "she could fulfil a ceremonial role despite her comparative youth".

The conspirators aimed to cause an uprising in the Midlands to coincide with the explosion in London and at this point secure Elizabeth's accession as a puppet queen. She would then be brought up as a Catholic and later married to a Catholic bridegroom. The plot failed when the conspirators were betrayed, and Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educate ...

was caught by the King's soldiers before he was able to ignite the powder.

Education

Elizabeth was given a comprehensive education for a princess at that time. This education included instruction in natural history, geography, theology, languages, writing, music, and dancing. She was denied instruction in the classics as her father believed that "Latin had the unfortunate effect of making women more cunning". By the age of 12, Elizabeth was fluent in several languages, including French, "which she spoke with ease and grace" and would later use to converse with her husband. She was also an excellent rider, had a thorough understanding of the Protestant religion, and had an aptitude for writing letters that "sounded sincere and never stilted". She also was extremely literary, and "several mementoes of her early love of books exist".Courtship and marriage

Suitors

As the daughter of a reigning monarch, the hand of the young Elizabeth was seen as a very desirable prize. Suitors came from across the continent and were many and varied. They included: *Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December ld Style and New Style dates, N.S 19 December15946 November ld Style and New Style dates, N.S 16 November1632), also known in English as Gustav II Adolf or Gustav II Adolph, was King of Sweden from 1611 t ...

, son (and later successor) of the King of Sweden

* Frederic Ulric, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

* Prince Maurice of Nassau

* Theophilus Howard, Lord Howard of Walden, later second Earl of Suffolk

* Otto, Hereditary Prince of Hesse-Kassel, son of Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

Maurice of Hesse-Kassel (; 25 May 1572 – 15 March 1632), also called Maurice the Learned or Moritz, was the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) in the Holy Roman Empire from 1592 to 1627.

Life

Maurice was born in Kassel as the son o ...

* Victor Amadeus, Prince of Piedmont

Victor Amadeus of Savoy (Vittorio Amedeo Filippo Giuseppe; 6 May 1699 – 22 March 1715) was the eldest son of Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy and his French wife Anne Marie d'Orléans. He was the heir apparent of Savoy from his birth and as suc ...

, the King of Spain's nephew and heir to the Duke of Savoy

* Philip III of Spain

Philip III (; 14 April 1578 – 31 March 1621) was King of Spain and King of Portugal, Portugal (where he is known as Philip II of Portugal) during the Iberian Union. His reign lasted from 1598 until his death in 1621. He held dominion over the S ...

, newly widowed in 1611.

Each suitor brought to the proposed marriage the prospect of power and greatness for the young Elizabeth.

Marriage could be of great benefit to her father's kingdom. When James had succeeded to the English throne in 1603, England had acquired a new role in European affairs. James, unlike the childless Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, by simply "having children, could play an important role in dynastic politics". The selection of Elizabeth's spouse, therefore, had little to do with her personal preference and a great deal to do with the benefits the match could bring.

Most of her suitors were rejected quickly for a variety of reasons. Some simply were not of high enough birth, had no real prospects to offer, or in the case of Gustavus Adolphus, who on all other grounds seemed like a perfect match, because "his country was at war with Queen Anne's native Denmark". Furthermore, England could not face another religious revolution, and therefore the religious pre-requisite was paramount.

The man chosen was Frederick (Friedrich) V, Count Palatine of the Rhine. Frederick was of undeniably high lineage. His ancestors included the kings of Aragon and Sicily, the landgraves of Hesse, the dukes of Brabant and Saxony, and the counts of Nassau and Leuven. He and Elizabeth also shared a common ancestor in Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

. He was "a senior Prince of the Empire" and a staunch defender of the Protestant faith.

Courtship

Frederick arrived in England on 16 October 1612, and the match seemed to please them both from the beginning. Their contemporaries noted how Frederick seemed to "delight in nothing but her company and conversation". Frederick also struck up a friendship with Elizabeth's elder brother, Prince Henry, which delighted his prospective bride immensely. King James did not take into consideration the couple's happiness, but saw the match as "one step in a larger process of achieving domestic and European concord". The only person seemingly unhappy with the match was Queen Anne. As the daughter of a king, the sister of a king, the wife of a king, and the mother of a future king, she also desired to be the mother of a queen. She is said to have been somewhat fond of Frederick's mild manner and generous nature but simply felt that he was of low stock. On 6 November 1612, Henry, Prince of Wales, died. His death took an emotional toll on Elizabeth, and her new position as second-in-line to the throne made her an even more desirable match. Queen Anne and those like-minded who had "always considered the Palsgrave to be an unworthy match for her, were emboldened in their opposition". Elizabeth stood by Frederick, whom her brother had approved, and whom she found to have the sentiments of a fine gentleman. Above all, he was "regarded as the future head of the Protestant interest in Germany".Marriage to Frederick V

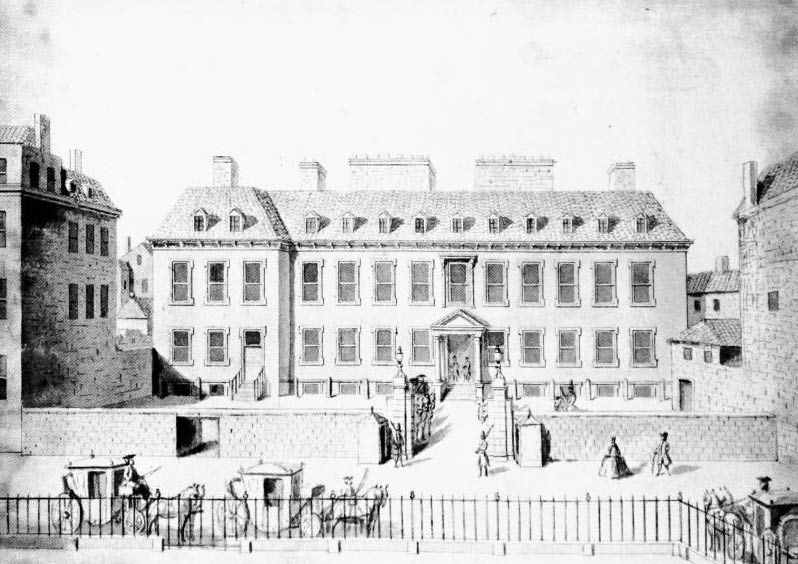

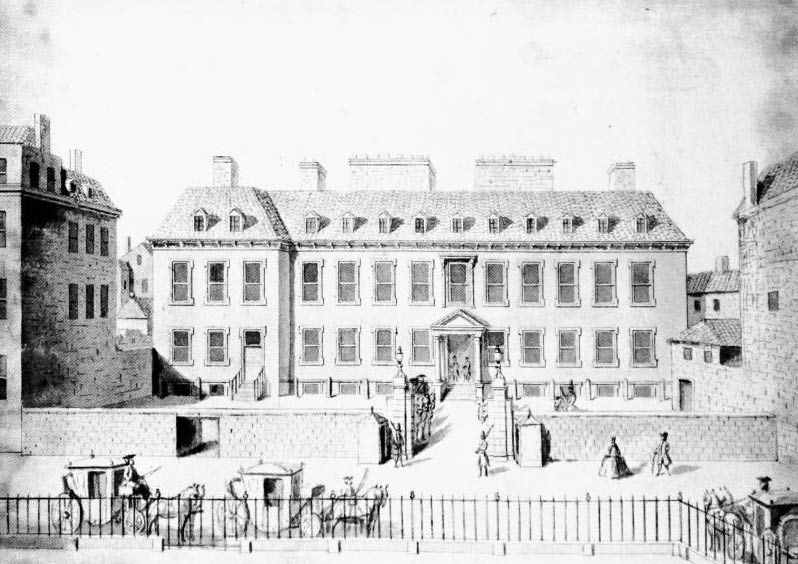

The wedding took place on 14 February 1613 at the royal chapel at thePalace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, ...

and was a grand occasion that saw more royalty than ever visit the court of England. The marriage was an enormously popular match and was the occasion for an outpouring of public affection with the ceremony described as "a wonder of ceremonial and magnificence even for that extravagant age".

It was celebrated with lavish and sophisticated festivities both in London and Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, including mass feasts and lavish furnishings that cost nearly £50,000, and nearly bankrupted King James. Among many celebratory writings of the events was John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

's "Epithalamion, Or Marriage Song on the Lady Elizabeth, and Count Palatine being married on St Valentine's Day". A contemporary author viewed the whole marriage as a prestigious event that saw England "lend her rarest gem, to enrich the Rhine".

Electress Palatine

After almost a two-month stay in London for continued celebrations, the couple began their journey to join the Electoral court in Heidelberg. The journey was filled with meeting people, sampling foods and wines, and being entertained by a wide variety of performers and companies. At each place the young couple stopped, Elizabeth was expected to distribute presents. The cash to allow her to do so was not readily available, so she had to use one of her own jewels as collateral so that the goldsmith Abraham Harderet would "provide her with suitable presents on credit".menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern zoo or zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, referring to ...

, and the beginnings of a new garden in the Italian Renaissance garden

The Italian Renaissance garden was a new style of garden which emerged in the late 15th century at villas in Rome and Florence, inspired by classical ideals of order and beauty, and intended for the pleasure of the view of the garden and the land ...

style popular in England at the time. The garden, the '' Hortus Palatinus'', was constructed by Elizabeth's former tutor, Salomon de Caus

Salomon de Caus (1576, Dieppe – 1626, Paris) was a French Huguenot engineer, once (falsely) credited with the development of the steam engine.

Biography

Caus was the elder brother of Isaac de Caus. Being a Huguenot, Caus spent his life moving ...

. It was dubbed the "Eighth Wonder of the World" by contemporaries.

Although Elizabeth and Frederick were considered to be genuinely in love and remained a romantic couple throughout the course of their marriage, problems already had begun to arise. Before the couple had left England, King James had made Frederick promise that Elizabeth "would take precedence over his mother ... and always be treated as if she were a Queen". This at times made life in the Palatinate uncomfortable for Elizabeth, for Frederick's mother Louise Juliana had "not expected to be demoted in favour of her young daughter-in-law" and, as such, their relationship was never more than civil.

Elizabeth gave birth to three children in Heidelberg: Frederick Henry, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate (sometimes called Henry Frederick) was born in 1614,

Although Elizabeth and Frederick were considered to be genuinely in love and remained a romantic couple throughout the course of their marriage, problems already had begun to arise. Before the couple had left England, King James had made Frederick promise that Elizabeth "would take precedence over his mother ... and always be treated as if she were a Queen". This at times made life in the Palatinate uncomfortable for Elizabeth, for Frederick's mother Louise Juliana had "not expected to be demoted in favour of her young daughter-in-law" and, as such, their relationship was never more than civil.

Elizabeth gave birth to three children in Heidelberg: Frederick Henry, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate (sometimes called Henry Frederick) was born in 1614, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

in 1617, and Elisabeth in 1618.

Queen of Bohemia

In 1619 Elizabeth's husband Frederick was one of those offered the throne of Bohemia. TheKingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia (), sometimes referenced in English literature as the Czech Kingdom, was a History of the Czech lands in the High Middle Ages, medieval and History of the Czech lands, early modern monarchy in Central Europe. It was the pr ...

was "an aristocratic republic in all but name", whose nobles elected the monarch. It was one of the few successful pluralist states. The country had enjoyed a long period of religious freedom, but in March 1619, on the death of Emperor Matthias Matthias is a name derived from the Greek Ματθαίος, in origin similar to Matthew.

Notable people

Notable people named Matthias include the following:

Religion

* Saint Matthias, chosen as an apostle in Acts 1:21–26 to replace Judas Isca ...

, this seemed about to change. The Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

heir, Archduke Ferdinand, crowned King of Bohemia in 1617, was a fervent Catholic who brutally persecuted Protestants in his Duchy of Styria

Styria ( ; ; ; ) is an Austrian Federal states of Austria, state in the southeast of the country. With an area of approximately , Styria is Austria's second largest state, after Lower Austria. It is bordered to the south by Slovenia, and cloc ...

. The Bohemian nobles had to choose between "either accepting Ferdinand as their king after all or taking the ultimate step of deposing him". They decided on deposition, and, when others declined because of the risks involved, the Bohemians "pandered to the elector's royalist pretensions" and extended the invitation to Elizabeth's husband.

Frederick, although doubtful, was persuaded to accept. Elizabeth "appealed to his honour as a prince and a cavalier, and to his humanity as a Christian", aligning herself with him completely. The family moved to Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, where "the new King was received with genuine joy". Frederick was crowned officially in the St. Vitus Cathedral at the Prague Castle

Prague Castle (; ) is a castle complex in Prague, Czech Republic serving as the official residence and workplace of the president of the Czech Republic. Built in the 9th century, the castle has long served as the seat of power for List of rulers ...

on 4 November 1619. The coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

of Elizabeth as Queen of Bohemia followed three days later.

The royal couple's third son, Prince Rupert, was born in Prague one month after the coronation. There was great popular rejoicing. Thus, Frederick's reign in Bohemia had begun well, but only lasted one year. The Bohemian crown "had always been a corner-stone of Habsburg policy" and the heir, Ferdinand, now Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Ferdinand II, would not yield. Frederick's reign ended with the defeat of Bohemian Protestant armies at the Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain (; ) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years.

It was fought on 8 November 16 ...

(which ended the first phase of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

) on 8 November 1620.

Elizabeth is remembered as the "Winter Queen", and Frederick as the "Winter King", in reference to the brevity of their reign, and to the season of the battle.

Exile

Fearing the worst, by the time of the defeat at theBattle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain (; ) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years.

It was fought on 8 November 16 ...

, Elizabeth already had left Prague and was awaiting the birth of her fifth child at the Castle of Custrin, about from Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. It was there on 6 January 1621 that she "in an easy labour lasting little more than an hour" was delivered of a healthy son, Maurice.

The military defeat removed the prospect of returning to Prague, and the entire family was forced to flee. They could no longer return to the Palatinate as it was occupied by the Catholic league and a Spanish contingent. Hence, after an invitation from the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by the stadtholders of, and then the heirs apparent of ...

, they moved to The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

.

Elizabeth arrived in The Hague in spring 1621 with only a small court. Her sense of duty to assist her husband out of the political mess in which they had found themselves meant that "she became much more an equal, if not the stronger, partner in the marriage". Her lady-in-waiting, Amalia van Solms, soon became involved with Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, and married him in 1625. The two women became rivals at the court of The Hague.

While in exile Elizabeth produced eight more children, four boys and four girls. The last, Gustavus, was born on 2 January 1632 and baptised in the Cloister Church where two of his siblings who had died young, Louis and Charlotte, were buried. Later that same month, Frederick said farewell to Elizabeth and set out on a journey to join the king of Sweden on the battlefield. After declining conditions set out by King Gustavus Adolphus that would have seen the Swedish king assist in his restoration, the pair parted with Frederick heading back toward The Hague. He had been ill with an infection since the beginning of October 1632, and died on the morning of 29 November before reaching The Hague.

Widowhood

When Elizabeth received the news of Frederick's death, she became senseless with grief and for three days did not eat, drink, or sleep. When Charles I heard of Elizabeth's state, he invited her to return to England, but she refused. The rights of her son and Frederick's heir Charles Louis "remained to be fought for". Elizabeth then fought for her son's rights, but she remained in The Hague even after he regained theElectorate of the Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate was a Imperial State, constituent state of the Holy Roman Empire until it was annexed by the Electorate of Baden in 1803. From the end of the 13th century, its ruler was one of the Prince-electors who elected the Holy ...

in 1648. She became a patron of the arts, and commissioned a larger family portrait to honour herself and her husband, to complement the impressive large seascape of her 1613 joyous entry to the Netherlands. Her memorial family portrait of 1636 was outdone by Amalia van Solms, who commissioned the Oranjezaal after the death of her husband Frederick Henry in 1648–1651.

Gerard van Honthorst

Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch: ''Gerrit van Honthorst''; 4 November 1592 – 27 April 1656) was a Dutch Golden Age painting, Dutch Golden Age painter who became known for his depiction of artificially lit scenes, eventually receiving the nickn ...

.

File:Bust of Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia. Marble, circa 1641 CE. By Francois Dieussart. From the Dutch Republic, Now the Netherlands. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.jpg, Marble bust of ''Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia'', circa 1641, by François Dieussart.

File:Gerard van Honthorst 007.jpeg, ''Elizabeth Stuart as a Widow'', 1642, by Gerard van Honthorst

Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch: ''Gerrit van Honthorst''; 4 November 1592 – 27 April 1656) was a Dutch Golden Age painting, Dutch Golden Age painter who became known for his depiction of artificially lit scenes, eventually receiving the nickn ...

.

Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

in 1650, Henriette Marie in 1651, and Maurice in 1652. Her brother Charles I, King of England was executed in early 1649, and the surviving Stuart family was exiled during the years of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

. The relationships with her remaining living children also became somewhat estranged, although she did spend time with her growing number of grandchildren. She began to pay the price for having been "a distant mother to most of her own children", and the idea of going to England now was uppermost in her thoughts.

Death

In 1660, the Stuarts were

In 1660, the Stuarts were restored

''Restored'' is the fourth studio album by American contemporary Christian musician Jeremy Camp. It was released on November 16, 2004, by BEC Recordings.

Track listing

Standard release

Enhanced edition

Deluxe gold edition

Standard Aus ...

to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland in the person of Elizabeth's nephew Charles II. Elizabeth arrived in England on 26 May 1661. By July, she was no longer planning on returning to The Hague and made plans for the remainder of her furniture, clothing, and other property to be sent to her. She then proceeded to move to Drury House, where she established a small, but impressive and welcoming, household. On 29 January 1662 she made another move, to Leicester House, Westminster, but by this time she was quite ill. Elizabeth caught pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, bled from her lungs on 10 February 1662 and died soon after midnight on 13 February.

Her death caused little public stir as by then her "chief, if not only, claim to fame n Londonwas as the mother of Rupert of the Rhine, the legendary Cavalier general". On the evening of 17 February, when her coffin (into which her remains had been placed the previous day) left Somerset House

Somerset House is a large neoclassical architecture, neoclassical building complex situated on the south side of the Strand, London, Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadran ...

, Rupert was the only one of her sons to follow the funeral procession to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. There in the chapel of Henry VII, "a survivor of an earlier age, isolated and without a country she could really call her own", she was laid to rest among her ancestors and close to her beloved elder brother, Henry, Prince of Wales, in the Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

vault.

Issue

Elizabeth and Frederick had 13 children, six of whom outlived their mother: # Henry Frederick, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate (1614–1629); drowned # Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine (1617–1680); married Charlotte of Hesse-Kassel, had issue including Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine, Duchess of Orleans; married Marie Luise von Degenfeld, had issue; married again Elisabeth Holländer von Berau (1659-1702), had issue #Elisabeth of the Palatinate

Elisabeth of the Palatinate (; 26 December 1618 – 11 February 1680), also known as Elisabeth of Bohemia (), Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate, or Princess-Abbess of Herford Abbey, was the eldest daughter of Frederick V, Elector Palatine (w ...

(1618–1680)

# Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine (1619–1682); had two illegitimate children

# Maurice of the Palatinate

Maurice, Prince Palatine of the Rhine KG (16 January 1621 – 1 September 1652) was the fourth son of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King James VI and I and Anne of Denmark.

Life

Maurice was present with h ...

(16 January 1621 – 1 September 1652)

# Louise Hollandine of the Palatinate (18 April 162211 February 1709)

# Louis (21 August 162424 December 1624)

# Edward, Count Palatine of Simmern (1625–1663); married Anne Gonzaga, had issue

# Henriette Marie of the Palatinate (7 July 162618 September 1651); married Prince Sigismund Rákóczi

The House of Rákóczi (older spelling Rákóczy) was a Hungarian nobility, Hungarian noble family in the Kingdom of Hungary between the 13th century and 18th century. Their name is also spelled ''Rákoci'' (in Slovakia), ''Rakoczi'' and ''Rako ...

, brother of George II Rákóczi, Prince of Transylvania, on 16 June 1651

# John Philip Frederick of the Palatinate (26 September 162716 February 1650); also reported to have been born on 15 September 1629

# Charlotte of the Palatinate (19 December 162814 January 1631)

# Sophia, Electress of Hanover (14 October 16308 June 1714); married Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover, had issue, including King George I of Great Britain

George I (George Louis; ; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the Electorate of Hanover within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. ...

. Many other royal families are Sophia's, and therefore, Elizabeth's, descendants. Sophia came close to ascending to the British throne, but died two months before Queen Anne.

# Gustavus Adolphus of the Palatinate (14 January 16321641)

Ancestry and family tree

Legacy

Under the EnglishAct of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement ( 12 & 13 Will. 3. c. 2) is an act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catho ...

, the succession to the English and Scottish crowns (later British crown) was settled on Elizabeth's youngest daughter Sophia of Hanover and her issue. In August 1714, Sophia's son (Elizabeth's grandson) George I ascended to the throne, with the future Royal family all his descendants and hence, also descendants of Elizabeth.

The Elizabeth River in colonial Southeastern Virginia was named in honour of the princess, as was Cape Elizabeth, a peninsula (and today a town) in the United States in the state of Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. John Smith explored and mapped New England and gave names to places mainly based on the names used by Native Americans. When Smith presented his map to Charles I, he suggested that the king should feel free to change the "barbarous names" for "English" ones. The king made many such changes, but only four survive today, one of which is Cape Elizabeth.

According to legend, William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven, built Ashdown House in Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

, England, in honour of Elizabeth, although she died before the house was completed.

Literary references

*The Polish baroque poet Daniel Naborowski wrote a short poem praising Elizabeth's eyes. He had seen her in 1609, when he visited London on a diplomatic mission. * A poem in praise of Elizabeth was written by the courtier and poet SirHenry Wotton

Sir Henry Wotton (; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg in 1604, he famously said "An amba ...

*The Winter Queen plays a seminal role in Neal Stephenson

Neal Town Stephenson (born October 31, 1959) is an American writer known for his works of speculative fiction. His novels have been categorized as science fiction, historical fiction, cyberpunk, and baroque.

Stephenson's work explores mathemati ...

's ''The Baroque Cycle

''The Baroque Cycle'' is a series of novels by American writer Neal Stephenson. It was published in three volumes containing eight books in 2003 and 2004. The story follows the adventures of a sizable cast of characters living amidst some of th ...

'' which is largely set during her lifetime.

* Elizabeth is a main character in Daniel Kehlmann

Daniel Kehlmann (; born 13 January 1975) is a German-language novelist and playwright of both Austrian and German nationality.Tyll'' (2017).

Royal weddings in history: a Stuart Valentine, Elizabeth and Frederick, National Archives

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Bohemia, Elizabeth Of 1596 births 1662 deaths People from Dunfermline 17th-century Scottish people 17th-century Scottish women 17th-century English women Heirs presumptive to the Scottish throne Heirs presumptive to the English throne Scottish princesses English princesses Queens consort of Bohemia Electresses of the Palatinate Elizabeth German people of the Thirty Years' War Burials at Westminster Abbey Children of James VI and I Daughters of kings Mothers of German monarchs Frederick V of the Palatinate

See also

* Scotland and the Thirty Years' WarBibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Kassel, Richard (2006), ''The Organ: An Encyclopedia,'' London: Routledge. * * * Spencer, Charles (2008) ''Prince Rupert: the Last Cavalier,'' London: Phoenix. * (alternative ) * * * * Williams, Deanne (2014), "A Dancing Princess," ''Shakespeare and the Performance of Girlhood'' (New York: Palgrave, 2014): 127-148. * , devotes its early chapters to describing her 1613 wedding and the reputation she and her husband had in Europe at the time.References

External links

* *Royal weddings in history: a Stuart Valentine, Elizabeth and Frederick, National Archives

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Bohemia, Elizabeth Of 1596 births 1662 deaths People from Dunfermline 17th-century Scottish people 17th-century Scottish women 17th-century English women Heirs presumptive to the Scottish throne Heirs presumptive to the English throne Scottish princesses English princesses Queens consort of Bohemia Electresses of the Palatinate Elizabeth German people of the Thirty Years' War Burials at Westminster Abbey Children of James VI and I Daughters of kings Mothers of German monarchs Frederick V of the Palatinate