Dōgen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

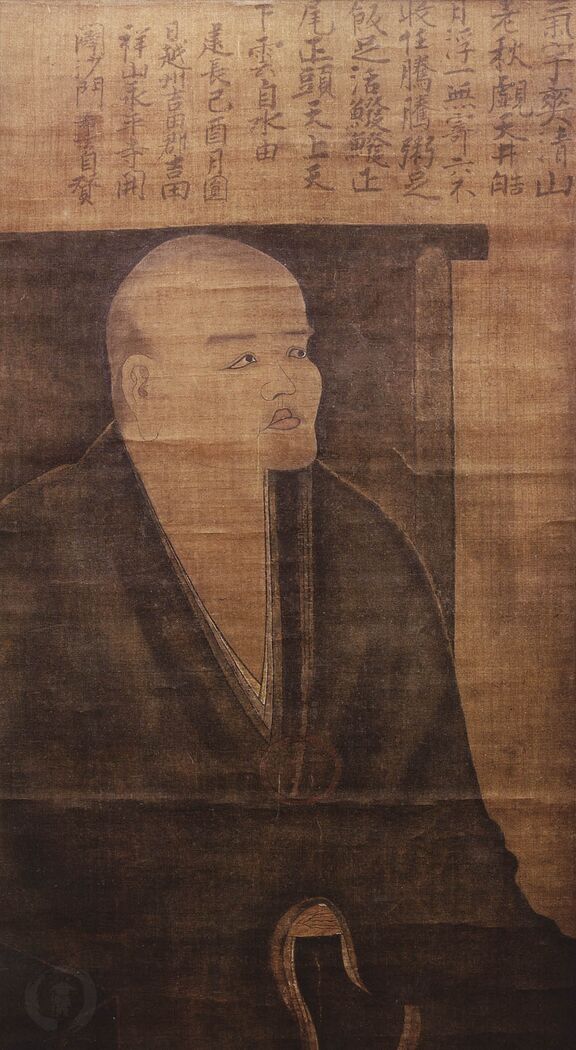

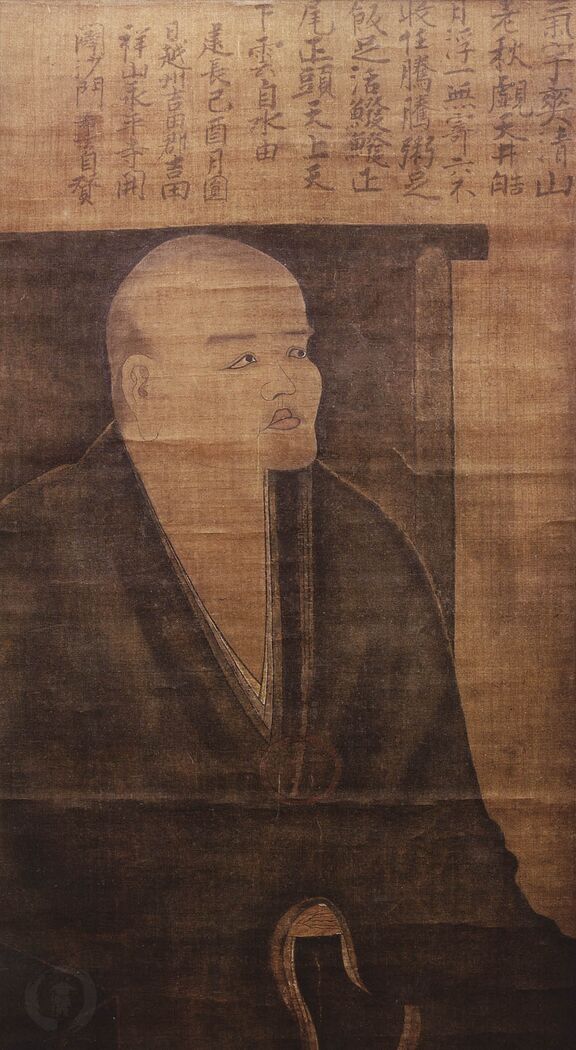

was a Japanese Zen

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at

Fifty-four years lighting up the sky.

A quivering leap smashes a billion worlds.

Hah!

Entire body looks for nothing.

Living, I plunge into Yellow Springs.

While Dōgen emphasized the importance and centrality of zazen, he did not reject other traditional Buddhist practices, and his monasteries performed various traditional ritual practices.Foulk, T. Griffith. 1999

While Dōgen emphasized the importance and centrality of zazen, he did not reject other traditional Buddhist practices, and his monasteries performed various traditional ritual practices.Foulk, T. Griffith. 1999

"History of the Soto Zen School."

from ''Dogen Zen and Its Relevance for Our Time: An International Symposium Held in Celebration of the 800th Anniversary of the Birth of Dōgen-zenji : Kresge Auditorium, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.'' Dōgen's monasteries also followed a strict monastic code based on the Chinese Chan codes and Dōgen often quotes these and various

While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese '' waka'' style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions".

While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese '' waka'' style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions".

Who is Dogen Zenji?

Message from Dogen

Translations of Dogen and other works by Anzan Hoshin.

Understanding the Shobogenzo

by Gudo Nishijima

by John Daido Loori

Shusho-gi, Online Translation

by Neil Christopher

Gakudo Yojin-shu, Online Translation

by Neil Christopher

Shushogi

What is Truly Meant by Training and Enlightenment

free for download

Zen Master Dogen

Dogen-related translations, books, articles and other media. Includes related video teachings from modern Zen masters. {{DEFAULTSORT:Dogen 1200 births 1253 deaths Zen Buddhism writers Zen Buddhist priests Japanese scholars of Buddhism Japanese philosophers Japanese religious leaders Japanese Zen Buddhists 13th-century Buddhists 13th-century scholars 13th-century Japanese philosophers Founders of religions Founders of Buddhist sects Buddhist poets

Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

, writer

A writer is a person who uses written words in different writing styles, genres and techniques to communicate ideas, to inspire feelings and emotions, or to entertain. Writers may develop different forms of writing such as novels, short sto ...

, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, and founder of the Sōtō

Sōtō Zen or is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Caodong school, Cáodòng school, which was founded during the ...

school of Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dentō Kokushi ().

Originally ordained as a monk in the Tendai School in Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

, he was ultimately dissatisfied with its teaching and traveled to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

to seek out what he believed to be a more authentic Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

. He remained there for four years, finally training under Tiāntóng Rújìng, an eminent teacher of the Cáodòng lineage of Chinese Chan. Upon his return to Japan, he began promoting the practice of zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

(sitting meditation) through literary works such as '' Fukanzazengi'' and '' Bendōwa''.

He eventually broke relations completely with the powerful Tendai School, and, after several years of likely friction between himself and the establishment, left Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

for the mountainous countryside where he founded the monastery Eihei-ji

file:Plan Eihei-ji.svg, 250px

is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest single religious denomination in Japan (by number of temples in a single legal entity). The other is Sōji-ji in Yokohama. Eihei-ji is loc ...

, which remains the head temple of the Sōtō school today.

Dōgen is known for his extensive writings like the ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' (''Treasury of the True Dharma Eye'', considered his magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

), the '' Eihei Kōroku'' (''Extensive Record,'' a collection of his talks), the '' Eihei Shingi'' (the first Japanese Zen monastic code), along with his Japanese poetry, and commentaries. Dōgen's writings are one of the most important sources studied in the contemporary Sōtō

Sōtō Zen or is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Caodong school, Cáodòng school, which was founded during the ...

Zen tradition.

Biography

Early life

Dōgen was probably born into a noble family, though as an illegitimate child of Minamoto Michichika. His foster father was his older brother Minamoto no Michitomo, who served in the imperial court as a high-ranking . His mother, named Ishi, the daughter of Matsudono Motofusa and a sister of the monk Ryōkan Hōgen, is said to have died when Dōgen was age 7.Early training

In 1212, the spring of his thirteenth year, Dōgen fled the house of his uncle Matsudono Moroie and went to his uncle Ryōkan Hōgen at the foot ofMount Hiei

is a mountain to the northeast of Kyoto, lying on the border between the Kyoto and Shiga Prefectures, Japan.

The temple of Enryaku-ji, the first outpost of the Japanese Tendai (Chin. Tiantai) sect of Buddhism, was founded atop Mount Hiei by ...

, the headquarters of the Tendai school of Buddhism. Stating that his mother's death was the reason he wanted to become a monk, Ryōkan sent the young Dōgen to Jien, an abbot at Yokawa on Mount Hiei. According to the ''Kenzeiki'' (), he became possessed by a single question with regard to the Tendai doctrine:

This question was, in large part, prompted by the Tendai concept of original enlightenment ( ''hongaku''), which states that all human beings are enlightened by nature and that, consequently, any notion of achieving enlightenment through practice is fundamentally flawed.

The ''Kenzeiki'' further states that he found no answer to his question at Mount Hiei, and that he was disillusioned by the internal politics and need for social prominence for advancement. Therefore, Dōgen left to seek an answer from other Buddhist masters. He went to visit Kōin, the Tendai abbot of Onjō-ji Temple (), asking him this same question. Kōin said that, in order to find an answer, he might want to consider studying Chán

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song d ...

in China. In 1217, two years after the death of contemporary Zen Buddhist Myōan Eisai, Dōgen went to study at Kennin-ji Temple (), under Eisai's successor, Myōzen ().

Travel to China

In 1223, Dōgen and Myōzen undertook the dangerous passage across theEast China Sea

The East China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. China names the body of water along its eastern coast as "East Sea" (, ) due to direction, the name of "East China Sea" is otherwise ...

to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

) to study in Jing-de-si (Ching-te-ssu, ) monastery as Eisai had once done. Around the time the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

was waging wars on the various dynasties of China.

In China, Dōgen first went to the leading Chan monasteries in Zhèjiāng province. At the time, most Chan teachers based their training around the use of '' gōng-àn'' (Japanese: ''kōan''). Though Dōgen assiduously studied the kōans, he became disenchanted with the heavy emphasis laid upon them, and wondered why the sutras were not studied more. At one point, owing to this disenchantment, Dōgen even refused Dharma transmission from a teacher. Then, in 1225, he decided to visit a master named Rújìng (; J. Nyojō), the thirteenth patriarch of the Cáodòng (J. Sōtō) lineage of Zen Buddhism, at Mount Tiāntóng's ( ''Tiāntóngshān''; J. Tendōzan) Tiāntóng temple in Níngbō. Rujing was reputed to have a style of Chan that was different from the other masters whom Dōgen had thus far encountered. In later writings, Dōgen referred to Rujing as "the Old Buddha". Additionally he affectionately described both Rujing and Myōzen as .

Under Rujing, Dōgen realized liberation of body and mind upon hearing the master say, "cast off body and mind" ( ''shēn xīn tuō luò''). This phrase would continue to have great importance to Dōgen throughout his life, and can be found scattered throughout his writings, as—for example—in a famous section of his '' Genjōkōan'' ():

Myōzen died shortly after Dōgen arrived at Mount Tiantong. In 1227, Dōgen received Dharma transmission

In Chan and Zen Buddhism, dharma transmission is a custom in which a person is established as a "successor in an unbroken lineage of teachers and disciples, a spiritual 'bloodline' ('' kechimyaku'') theoretically traced back to the Buddha him ...

and '' inka'' from Rujing, and remarked on how he had finally settled his "life's quest of the great matter".

Return to Japan

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at Kennin-ji

is a historic Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan, and head temple of its associated branch of Rinzai Buddhism. It is considered to be one of the so-called Kyoto ''Gozan'' or "five most important Zen temples of Kyoto".

History

Kennin-ji was ...

, where he had trained previously. Among his first actions upon returning was to write down the ''Fukanzazengi'' (; ''Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen''), a short text emphasizing the importance of and giving instructions for ''zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

'' (sitting meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

).

However, tension soon arose as the Tendai community began taking steps to suppress both Zen and Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran (founder)

S ...

, the new forms of Buddhism in Japan. In the face of this tension, Dōgen left the Tendai dominion of Kyōto in 1230, settling instead in an abandoned temple in what is today the city of Uji, south of Kyōto.

In 1233, Dōgen founded the Kannon-dōri-in in Fukakusa as a small center of practice. He later expanded this temple into Kōshōhōrin-ji ().

Eihei-ji

In 1243, Hatano Yoshishige () offered to relocate Dōgen's community toEchizen province

was a Provinces of Japan, province of Japan in the area that is today the northern portion of Fukui Prefecture in the Hokuriku region of Japan. Echizen bordered on Kaga Province, Kaga, Wakasa Province, Wakasa, Hida Province, Hida, and Ōmi Provin ...

, far to the north of Kyōto. Dōgen accepted this offer to relocate, because of the ongoing tension with the Tendai community, and the growing competition the Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

-school

His followers built a comprehensive center of practice there, calling it Daibutsu Temple (Daibutsu-ji, ). While the construction work was going on, Dōgen would live and teach at Yoshimine-dera Temple (Kippō-ji, ), which is located close to Daibutsu-ji. During his stay at Kippō-ji, Dōgen "fell into a depression". It marked a turning point in his life, giving way to "rigorous critique of Rinzai Zen". He criticized Dahui Zonggao, the most influential figure of Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

Chán.

In 1246, Dōgen renamed Daibutsu-ji, calling it Eihei-ji

file:Plan Eihei-ji.svg, 250px

is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest single religious denomination in Japan (by number of temples in a single legal entity). The other is Sōji-ji in Yokohama. Eihei-ji is loc ...

. This temple remains one of the two head temples of Sōtō Zen in Japan today, the other being Sōji-ji.

Dōgen spent the remainder of his life teaching and writing at Eihei-ji. In 1247, the newly installed shōgun's regent, Hōjō Tokiyori

was the fifth shikken (regent of shogun) of the Kamakura shogunate in Japan.

Early life

He was born to warrior monk Hōjō Tokiuji and a daughter of Adachi Kagemori, younger brother of Hōjō Tsunetoki, the fourth shikken, and grandson of ...

, invited Dōgen to come to Kamakura

, officially , is a city of Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. It is located in the Kanto region on the island of Honshu. The city has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 people per km2 over the tota ...

to teach him. Dōgen made the rather long journey east to provide the shōgun with lay ordination, and then returned to Eihei-ji in 1248. In the autumn of 1252, Dōgen fell ill, and soon showed no signs of recovering. He presented his robes to his main apprentice, Koun Ejō (), making him the abbot of Eihei-ji.

Death

At Hatano Yoshishige's invitation, Dōgen left for Kyōto in search of a remedy for his illness. In 1253, soon after arriving in Kyōto, Dōgen died. Shortly before his death, he had written adeath poem

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of the Sinosphere—most prominently in Culture of Japan, Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history, Joseon Korea, and Vietnam. They tend to offer a reflectio ...

:

Teachings

Zazen

Dōgen often stressed the critical importance ofzazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

, or sitting meditation as the central practice of Buddhism. He considered zazen to be identical to studying Zen. This is pointed out clearly in the first sentence of the 1243 instruction manual ''"Zazen-gi"'' (; "Principles of Zazen"): "Studying Zen ... is zazen". Dōgen taught zazen to everyone, even for the laity, male or female and including all social classes. In referring to zazen, Dōgen is most often referring specifically to '' shikantaza'', roughly translatable as "nothing but precisely sitting", or "just sitting," which is a kind of sitting meditation in which the meditator sits "in a state of brightly alert attention that is free of thoughts, directed to no object, and attached to no particular content". In his ''Fukan Zazengi'', Dōgen wrote:

Dōgen also described zazen practice with the term ''hishiryō'' (, "non-thinking", "without thinking", "beyond thinking"). According to Cleary, it refers to ''ekō henshō'', turning the light around, focussing awareness on awareness itself. It is a state of no-mind which one is simply aware of things as they are, beyond thinking and not-thinking - the active effort not to think. In the ''Fukanzazengi'', Dōgen writes:...settle into a steady, immobile sitting position. Think of not thinking (''fushiryō''). How do you think of not-thinking? Without thinking (''hishiryō''). This in itself is the essential art of zazen. The zazen I speak of is not learningMasanobu Takahashi writes that ''hishiryō'' is not a state of no mental activity whatsoever. Instead, it is a state "beyond thinking and not-thinking" and beyond affirmation and rejection. Other Japanese Dogen scholars link the term with the realization ofmeditation Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat .... It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss, the cultivation-authentication of totally culminated enlightenment. It is the presence of things as they are.

emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation, nihilism, and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression (mood), depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

wiktionary:despair, despair, or o ...

.Hee-Jin Kim. ''Eihei Dogen: Mystical Realist,'' pp. 62-63. Simon and Schuster, Jun 25, 2012 According to Thomas Kasulis, non-thinking refers to the "pure presence of things as they are", "without affirming nor negating", without accepting nor rejecting, without believing nor disbelieving. In short, it is a non-conceptual, non-intentional and "prereflective mode of consciousness" which does not imply that it is an experience without content. Similarly, Hee-Jin Kim describes this as an "objectless, subjectless, formless, goalless and purposeless" state which is yet not a blank void. As such, the correct mental attitude for zazen according to Dōgen is one of effortless non-striving, this is because for Dōgen, original enlightenment is already always present.

Other Buddhist practices

While Dōgen emphasized the importance and centrality of zazen, he did not reject other traditional Buddhist practices, and his monasteries performed various traditional ritual practices.Foulk, T. Griffith. 1999

While Dōgen emphasized the importance and centrality of zazen, he did not reject other traditional Buddhist practices, and his monasteries performed various traditional ritual practices.Foulk, T. Griffith. 1999"History of the Soto Zen School."

from ''Dogen Zen and Its Relevance for Our Time: An International Symposium Held in Celebration of the 800th Anniversary of the Birth of Dōgen-zenji : Kresge Auditorium, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.'' Dōgen's monasteries also followed a strict monastic code based on the Chinese Chan codes and Dōgen often quotes these and various

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

texts in his works. As such, monastic rules and decorum (saho) was an important element of Dōgen's teaching. One of the most important texts by Dōgen on this topic is the ''Pure Standards for the Zen Community'' ('' Eihei Shingi'').

Dōgen certainly saw zazen as the most important Zen practice, and saw other practices as secondary. He frequently relegates other Buddhist practices to a lesser status, as he writes in the '' Bendōwa'': "Commitment to Zen is casting off body and mind. You have no need for incense offerings, homage praying, nembutsu

file:玉里華山寺 (21)南無阿彌陀佛古碑.jpg, 250px, Chinese Nianfo carving

The Nianfo ( zh, t=wikt:念佛, 念佛, p=niànfó, alternatively in Japanese language, Japanese ; ; or ) is a Buddhist practice central to East Asian Buddhism. ...

, penance disciplines, or silent sutra readings; just sit single-mindedly." While Dōgen rhetorically critiques traditional practices in some passages, Foulk writes that "Dōgen did not mean to reject literally any of those standard Buddhist training methods". Rather, for Dōgen, one should engage in all practices without attachment and from the point of view of the emptiness of all things. It is from this perspective that Dōgen writes we should not engage in any "practice" (which is merely a conventional category which separates one kind of activity from another).

Indeed, according to Foulk:the specific rituals that seem to be disavowed in the ''Bendowa'' passage are all prescribed for Zen monks, often in great detail, in Dogen's other writings. In ''Kuyo shobutsu'', Dogen recommends the practice of offering incense and making worshipfulprostration Prostration is the gesture of placing one's body in a reverentially or submissively prone position. Typically prostration is distinguished from the lesser acts of bowing or kneeling by involving a part of the body above the knee, especially t ...s before Buddha images andstupas In Buddhism, a stupa (, ) is a domed hemispherical structure containing several types of sacred relics, including images, statues, metals, and '' śarīra''—the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns. It is used as a place of pilgrimage and m ..., as prescribed in the sutras and Vinaya texts. In ''Raihai tokuzui'' he urges trainees to revere enlightened teachers and to make offerings and prostrations to them, describing this as a practice which helps pave the way to one's own awakening. In ''Chiji shingi'' he stipulates that the vegetable garden manager in a monastery should participate together with the main body of monks in sutra chanting services (fugin), recitation services (nenju) in which buddhas' names are chanted (a form of nenbutsu practice), and other major ceremonies, and that he should burn incense and make prostrations (shoko raihai) and recite the buddhas' names in prayer morning and evening when at work in the garden. The practice of repentences (sange) is encouraged in Dogen's ''Kesa kudoku'', in his ''Sanji go'', and his ''Keisei sanshiki''. Finally, in ''Kankin'', Dogen gives detailed directions for sutra reading services (kankin) in which, as he explains, texts could be read either silently or aloud as a means of producing merit to be dedicated to any number of ends, including the satisfaction of wishes made by lay donors, or prayers on behalf of the emperor.

Oneness of practice-verification

The primary concept underlying Dōgen's Zen practice is "the oneness of practice-verification" or "the unity of cultivation and confirmation" ( ''shushō-ittō'' / ''shushō-ichinyo'').Carl Bielefeldt. ''Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation'', p. 137, University of California Press, 1990. The term ''shō'' (, verification, affirmation, confirmation, attainment) is also sometimes translated as " enlightenment", though this translation is also questioned by some scholars. The ''shushō-ittō'' teaching was first and most famously explained in the '' Bendōwa'' ( ''A Talk on the Endeavor of the Path'', c. 1231) as follows: In the '' Fukanzazengi'' (''Universal Recommendation for Zazen''), Dōgen explains how to practice zazen and then explains the nature of verificationIf you grasp the point of this [practice], the four elements [of the body] will become light and at ease, the spirit will be fresh and sharp, thoughts will be correct and clear; the flavor of the dharma will sustain the spirit, and you will be calm, pure, and joyful. Your daily life will be [the expression of] your true natural state. Once you achieve clarification [of the truth], you may be likened to the dragon gaining the water or the tiger taking to the mountains. You should realize that when right thought is present, dullness and agitation cannot intrude.

Buddha-nature

For Dōgen,buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

or ''busshō'' () is all of reality, "all things" (). In the ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'', Dōgen writes that "whole-being is the Buddha-nature" and that even inanimate objects (rocks, sand, water) are an expression of Buddha-nature. He rejected any view that saw buddha-nature as a permanent, substantial inner self or ground. Dōgen describes buddha-nature as "vast emptiness", "the world of becoming" and writes that "impermanence is in itself Buddha-nature". He writes in '' Busshō'',

Therefore, the very impermanency of grass and tree, thicket and forest is the Buddha nature. The very impermanency of men and things, body and mind, is the Buddha nature. Nature and lands, mountains and rivers, are impermanent because they are the Buddha nature. Supreme and complete enlightenment, because it is impermanent, is the Buddha nature.Takashi James Kodera writes that the main source of Dōgen's understanding of buddha-nature is a passage from the '' Nirvana sutra'' which was widely understood as stating that all sentient beings possess buddha-nature. However, Dōgen interpreted the passage differently, rendering it as follows:

All are () sentient beings, () all things are () the Buddha-nature (); the Tathagata () abides constantly (), is non-existent () yet existent (), and is change ().Kodera explains that "whereas in the conventional reading the Buddha-nature is understood as a permanent essence inherent in all sentient beings, Dōgen contends that all things are the Buddha-nature. In the former reading, the Buddha-nature is a change less potential, but in the latter, it is the eternally arising and perishing actuality of all things in the world." Thus for Dōgen buddha-nature includes everything, the totality of "all things", including inanimate objects like grass, trees and land (which are also "mind" for Dōgen).

Great realization / satori

Dōgen taught that through zazen one could attain "great realization" or "great enlightenment" ( ''daigo-tettei''), which is also calledsatori

''Satori'' () is a Japanese Buddhist term for " awakening", "comprehension; understanding". The word derives from the Japanese verb '' satoru''.

In the Zen Buddhist tradition, ''satori'' refers to a deep experience of '' kenshō'', "seeing ...

(, "understanding", "knowledge").Bielefeldt, Carl (1990). ''Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation'', p. 5. University of California Press.

According to Ko'un Yamada, Dōgen "repeatedly emphasizes the importance of each person attaining enlightenment". Dōgen writes about this in a fascicle of the ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' titled '' Daigo'', which states that when practitioners of Zen attain daigo they have risen above the discrimination between delusion and enlightenment.

While Dōgen did teach the importance of attaining enlightenment, he also critiqued certain ways of explaining it and teaching about it. According to Barbara O'Brien, Dōgen critiqued the term "''kenshō

Kenshō (Rōmaji; Japanese and classical Chinese: 見性, Pinyin: ''jianxing'', Sanskrit: dṛṣṭi- svabhāva) is an East Asian Buddhist term from the Chan / Zen tradition which means "seeing" or "perceiving" ( 見) "nature" or "essence" ...

''" because "the word ''kenshō'' means 'to see one's nature', which sets up a dichotomy between the seer and the object of seeing."O'Brien, Barbara (2019). ''The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World'', p. 204. Shambhala Publications. Furthermore, according to Bielefeldt, Dōgen's zazen is "a subtle state beyond either thinking or not thinking" in which "body and mind have been sloughed off". It is a state in which "all striving for religious experience, all expectation of satori (daigo), is left behind." As such, while Dōgen did not reject the importance of satori, he taught that we should not sit zazen with the goal of satori in mind.

Time-Being

Dōgen's conception of Being-Time or Time-Being ('' Uji'', ) is an essential element of his metaphysics in the ''Shōbōgenzō''. According to the traditional interpretation, "''Uji''" here means time itself is being, and all being is time." ''Uji'' is all the changing and dynamic activities that exist as the flow of becoming, all beings in the entire world are time. The two terms are thus spoken of concurrently to emphasize that the things are not to be viewed as separate concepts. Moreover, the aim is to not abstract time and being as rational concepts. This view has been developed by scholars such as Steven Heine, Joan Stambaugh and others and has served as a motivation to compare Dōgen's work to that of Martin Heidegger's " Dasein". Rein Raud has argued that this view is not correct and that Dōgen asserts that all existence is momentary, showing that such a reading would make quite a few of the rather cryptic passages in the ''Shōbōgenzō'' quite lucid.Perfect expression

Another essential element of Dōgen's 'performative' metaphysics is his conception of Perfect expression (''Dōtoku'', ). "While a radically critical view on language as soteriologically inefficient, if not positively harmful, is what Zen Buddhism is famous for," it can be argued "'within the framework of a rational theory of language, against an obscurantist interpretation of Zen that time and again invokes experience.'" Dōgen distinguishes two types of language: monji , the first, – after Ernst Cassirer – "discursive type that constantly structures our experiences and—more fundamentally—in fact produces the world we experience in the first place"; and dōtoku , the second, "presentative type, which takes a holistic stance and establishes the totality of significations through a texture of relations.". As Döll points out, "It is this second type, as Müller holds, that allows for a positive view of language even from the radically skeptical perspective of Dōgen’s brand of Zen Buddhism."Critique of Rinzai

Dōgen was sometimes critical of theRinzai school

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school, Linji s ...

for their formulaic and intellectual koan practice (such as the practice of the ''Shiryoken'' or "Four Discernments") as well as for their disregard for the sutras:

Recently in the great Sung dynasty of China there are many who call themselves "Zen masters". They do not know the length and breadth of the Buddha-Dharma. They have heard and seen but little. They memorize two or three sayings of Lin Chi and Yun Men and think this is the whole way of the Buddha-Dharma. If the Dharma of the Buddha could be condensed in two or three sayings of Lin Chi and Yun Men, it would not have been transmitted to the present day. One can hardly say that Lin Chi and Yun Men are the Venerable ones of the Buddha-Dharma.Dōgen was also very critical of the Japanese Daruma school of Dainichi Nōnin.

Virtues

Dogen's perspective of virtue is discussed in the ''Shōbōgenzō'' text as something to be practiced inwardly so that it will manifest itself on the outside. In other words, virtue is something that is both internal and external in the sense that one can practice internal good dispositions and also the expression of these good dispositions.Writings

While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese '' waka'' style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions".

While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese '' waka'' style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions".

Shōbōgenzō

Dōgen's masterpiece is the ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' (, "Treasury of the True Dharma Eye"), talks and writings collected together in ninety-five fascicles. The topics range from zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

, koan

A ( ; ; zh, c=公案, p=gōng'àn ; ; ) is a story, dialogue, question, or statement from Chinese Chan Buddhist lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen Buddhist practice in different ways. The main goal of practice in Z ...

s, Buddhist philosophy

Buddhist philosophy is the ancient Indian Indian philosophy, philosophical system that developed within the religio-philosophical tradition of Buddhism. It comprises all the Philosophy, philosophical investigations and Buddhist logico-episte ...

, monastic practice, the equality of women and men, to the philosophy of language, being, and time.

Shushō-gi

The ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' served as the basis for the short work entitled ''Shushō-gi'' (), which was compiled in 1890 by a layman named Ouchi Seiran (1845–1918) along with Takiya Takushū () of Eihei-ji and Azegami Baisen () of Sōji-ji. The compilation serves as an introductory compilation of key extracts from the ''Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' which help explain the foundational teachings and concepts of Dōgen Zen to a lay audience.

Shinji Shōbōgenzō

Dōgen also compiled a collection of 301 koans in Chinese without commentaries added. Often called the '' Shinji Shōbōgenzō'' (''shinji'': "original or true characters" and ''shōbōgenzō'', variously translated as "the right-dharma-eye treasury" or "Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma"). The collection is also known as the ''Shōbōgenzō Sanbyakusoku'' (The Three Hundred Verse Shōbōgenzō") and the ''Mana Shōbōgenzō'', where ''mana'' is an alternative reading of ''shinji''. The exact date the book was written is in dispute but Nishijima believes that Dogen may well have begun compiling the koan collection before his trip to China. Although these stories are commonly referred to as ''kōans'', Dōgen referred to them as ''kosoku'' (ancestral criteria) or ''innen'' (circumstances and causes or results, of a story). The word ''kōan'' for Dogen meant "absolute reality" or the "universal Dharma".Collections of dharma discourses

Lectures that Dōgen gave to his monks at his monastery,Eihei-ji

file:Plan Eihei-ji.svg, 250px

is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest single religious denomination in Japan (by number of temples in a single legal entity). The other is Sōji-ji in Yokohama. Eihei-ji is loc ...

, were compiled under the title '' Eihei Kōroku'', also known as ''Dōgen Oshō Kōroku'' (The Extensive Record of Teacher Dōgen's Sayings) in ten volumes. The sermons, lectures, sayings and poetry were compiled shortly after Dōgen's death by his main disciples, Koun Ejō

(1198–1280) was the second Lineage (Buddhism), patriarch of the Japanese Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism who lived during the Kamakura period. He was initially a disciple of the short-lived Darumashu, Darumashū sect of Japanese Zen founded by Non ...

(, 1198–1280), Senne, and Gien. There are three different editions of this text: the Rinnō-ji text from 1598, a popular version printed in 1672, and a version discovered at Eihei-ji in 1937, which, although undated, is believed to be the oldest extant version.

Another collection of his talks is the '' Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki'' (Gleanings from Master Dōgen's Sayings) in six volumes. These are talks that Dōgen gave to his leading disciple, Ejō, who became Dōgen's disciple in 1234. The talks were recorded and edited by Ejō.

Other writings

Other notable writings of Dōgen are: * '' Fukanzazengi'' (, General Advice on the Principles of Zazen), one volume; probably written immediately after Dōgen's return from China in 1227. * '' Bendōwa'' (, "On the Endeavor of the Way"), written in 1231. This represents one of Dōgen's earliest writings and asserts the superiority of the practice of shikantaza through a series of questions and answers. * ''Eihei shoso gakudō-yōjinshū'' (Advice on Studying the Way), one volume; probably written in 1234. * '' Tenzo kyōkun'' (Instructions to the Chief Cook), one volume; written in 1237. * ''Bendōhō'' (Rules for the Practice of the Way), one volume; written between 1244 and 1246. * The earliest work by Dōgen is the ''Hōkojōki'' (Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period). This one volume work is a collection of questions and answers between Dōgen and his Chinese teacher, Tiāntóng Rújìng (; Japanese: Tendō Nyojō, 1162–1228). The work was discovered among Dōgen's papers by Ejō in 1253, just three months after Dōgen's death.Lineage

Though Dogen emphasised the importance of the correct transmission of the Buddha dharma, as guaranteed by the line of transmission from Shakyamuni, his own transmission became problematic in the third generation. In 1267 Ejō retired as Abbot of Eihei-ji, giving way to Gikai, who was already favored by Dōgen. Gikai introduced esoteric elements into the practice. Opposition arose, and in 1272 Ejō resumed the position of abbot. Following Ejō's death in 1280, Gikai became abbot again, strengthened by the support of the military for magical practices. Opposition arose again, and Gikai was forced to leave Eihei-ji. He was succeeded by Gien, who was first trained in the Daruma-school of Nōnin. His supporters designated him as the third abbot, rejecting the legitimacy of Gien. *Koun Ejō

(1198–1280) was the second Lineage (Buddhism), patriarch of the Japanese Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism who lived during the Kamakura period. He was initially a disciple of the short-lived Darumashu, Darumashū sect of Japanese Zen founded by Non ...

, commentator on the ''Shōbōgenzō'', and former Darumashū elder

** Giin, through Ejō

** Gikai, through Ejō

*** Keizan

Keizan Jōkin (, 1268–1325), also known as Taiso Jōsai Daishi, is considered to be the second great founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. While Dōgen, as founder of Japanese Sōtō, is known as , Keizan is often referred to as .

Keiz ...

** Gien, through Ejō

* Senne, another commentator of the ''Shōbōgenzō''.

Jakuen, a student of Rujing, who traced his lineage "directly back the Zen of the Song period", established Hōkyō-ji, where a strict style of Zen was practised. Students of his played a role in the conflict between Giin and Gikai.

A notable successor of Dogen was Keizan

Keizan Jōkin (, 1268–1325), also known as Taiso Jōsai Daishi, is considered to be the second great founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. While Dōgen, as founder of Japanese Sōtō, is known as , Keizan is often referred to as .

Keiz ...

(; 1268–1325), founder of Sōji-ji Temple and author of the ''Record of the Transmission of Light'' ( '' Denkōroku''), which traces the succession of Zen masters from Siddhārtha Gautama up to Keizan's own day. Together, Dōgen and Keizan are regarded as the founders of the Sōtō school in Japan.

Miraculous events and auspicious signs

Several "miraculous experiences" and "auspicious signs" have been recorded in Dōgen's life,, , , some of them quite famous. According to Bodiford, "Monks and laymen recorded these events as testaments to his great mystical power," which "helped confirm the legacy of Dōgen's teachings against competing claims made by members of the Buddhist establishment and other outcast groups." Bodiford further notes that the "magical events at Eiheiji helped identify the temple as a cultic center," putting it at a par with other temples where supernatural events occurred. According to Faure, for Dōgen these auspicious signs were proof that "Eiheiji was the only place in Japan where the Buddhist Dharma was transmitted correctly and that this monastery was thus rivaled by no other." In Menzan Zuihō's well-known 1753 edition of Dōgen's biography, it records that while traveling in China with his companion Dōshō, Dōgen became very ill, and a deity appeared before him who gave him medicine which instantly healed him: This medicine, which later became known as Gedokuen or "Poison-Dispelling Pill" was then produced by the Sōtō church until the Meiji Era, and was commonly sold nationwide as an herbal medicine, and became a source of income for the Sōtō church. Another famous incident happened when he was returning to Japan from China. The ship he was on was caught in a storm. In this instance, the storm became so severe, that the crew feared the ship would sink and kill them all. Dōgen then began leading the crew in recitation of chants to Kannon (Avalokiteshwara), during which, the Bodhisattva appeared before him, and several of the crew saw her as well. After the vision appeared, the storm began to calm down, and consensus of those aboard was that they had been saved due to the intervention of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshwara. This story is repeated in official works sponsored by the Sōtō Shū Head Office and there is even a sculpture of the event in a water treatment pond in Eihei-ji Temple. Additionally, there is a 14th-century copy of a painting of the same Kannon, that was supposedly commissioned by Dōgen, that includes a piece of calligraphy that is possibly an original in Dōgen's own hand, recording his gratitude to Avalokiteshwara: Another miraculous event occurred, while Dōgen was at Eihei-ji. During a ceremony of gratitude for the 16 Celestial Arahants (called Rakan in Japanese), a vision of 16 Arahants appeared before Dōgen descending upon a multi-colored cloud, and the statues of the Arahants that were present at the event began to emanate rays of light, to which Dōgen then exclaimed: Dōgen was profoundly moved by the entire experience, and took it as an auspicious sign that the offerings of the ceremony had been accepted. In his writings he wrote: Dōgen is also recorded to have had multiple encounters with non-human beings. Aside from his encounter with the kami Inari in China, in the Denkōrou it is recorded that while at Kōshō-ji, he was also visited by a deva who came to observe during certain ceremonies, as well as a dragon who visited him at Eihei-Ji and requested to be given the eight abstinence Precepts:See also

*''Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

'' - 2009 Japanese biopic about the life of Dōgen

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * . * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Who is Dogen Zenji?

Message from Dogen

Translations of Dogen and other works by Anzan Hoshin.

Understanding the Shobogenzo

by Gudo Nishijima

by John Daido Loori

Shusho-gi, Online Translation

by Neil Christopher

Gakudo Yojin-shu, Online Translation

by Neil Christopher

Shushogi

What is Truly Meant by Training and Enlightenment

free for download

Dogen-related translations, books, articles and other media. Includes related video teachings from modern Zen masters. {{DEFAULTSORT:Dogen 1200 births 1253 deaths Zen Buddhism writers Zen Buddhist priests Japanese scholars of Buddhism Japanese philosophers Japanese religious leaders Japanese Zen Buddhists 13th-century Buddhists 13th-century scholars 13th-century Japanese philosophers Founders of religions Founders of Buddhist sects Buddhist poets