Déclaration Des Droits De L'Homme Et Du Citoyen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

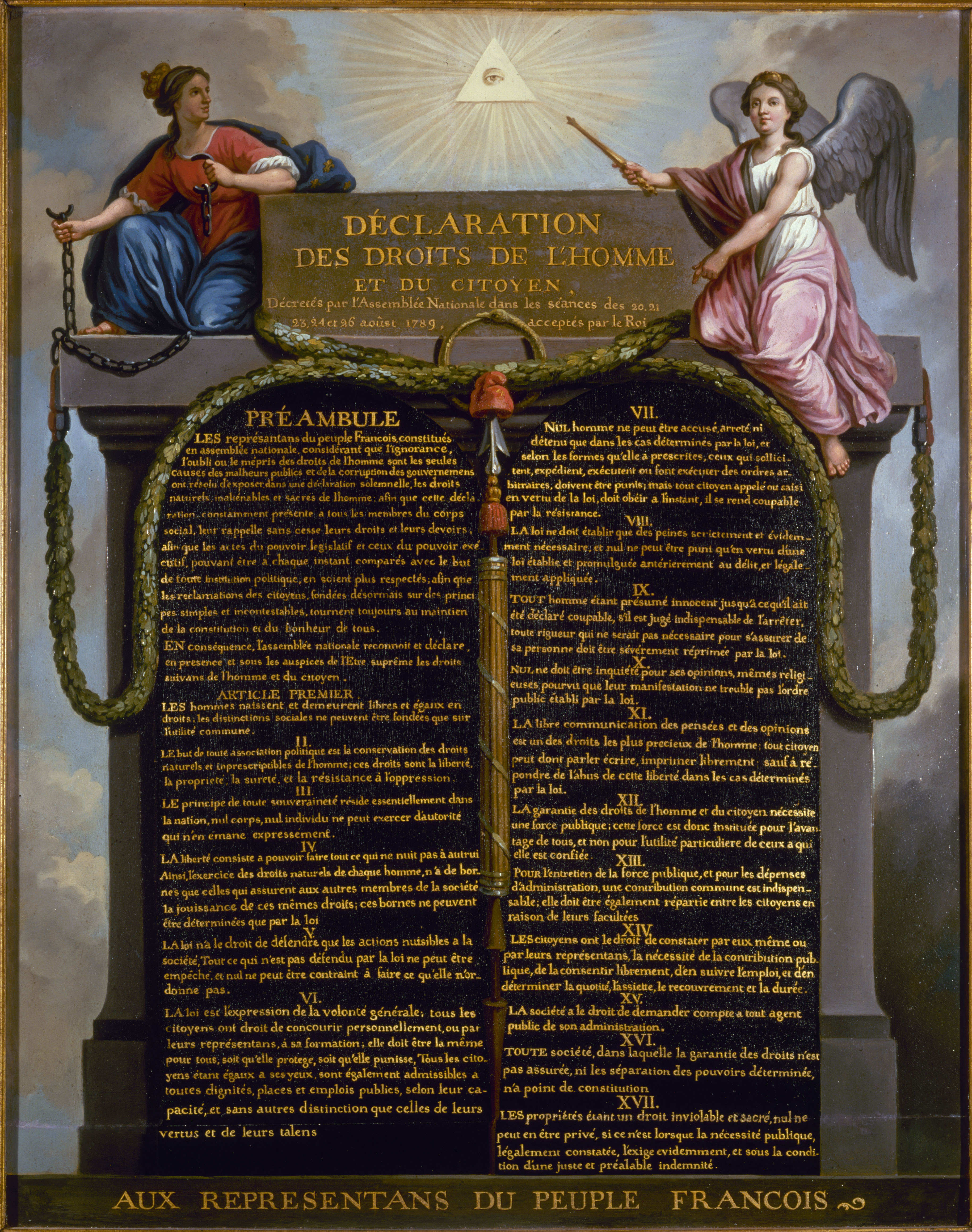

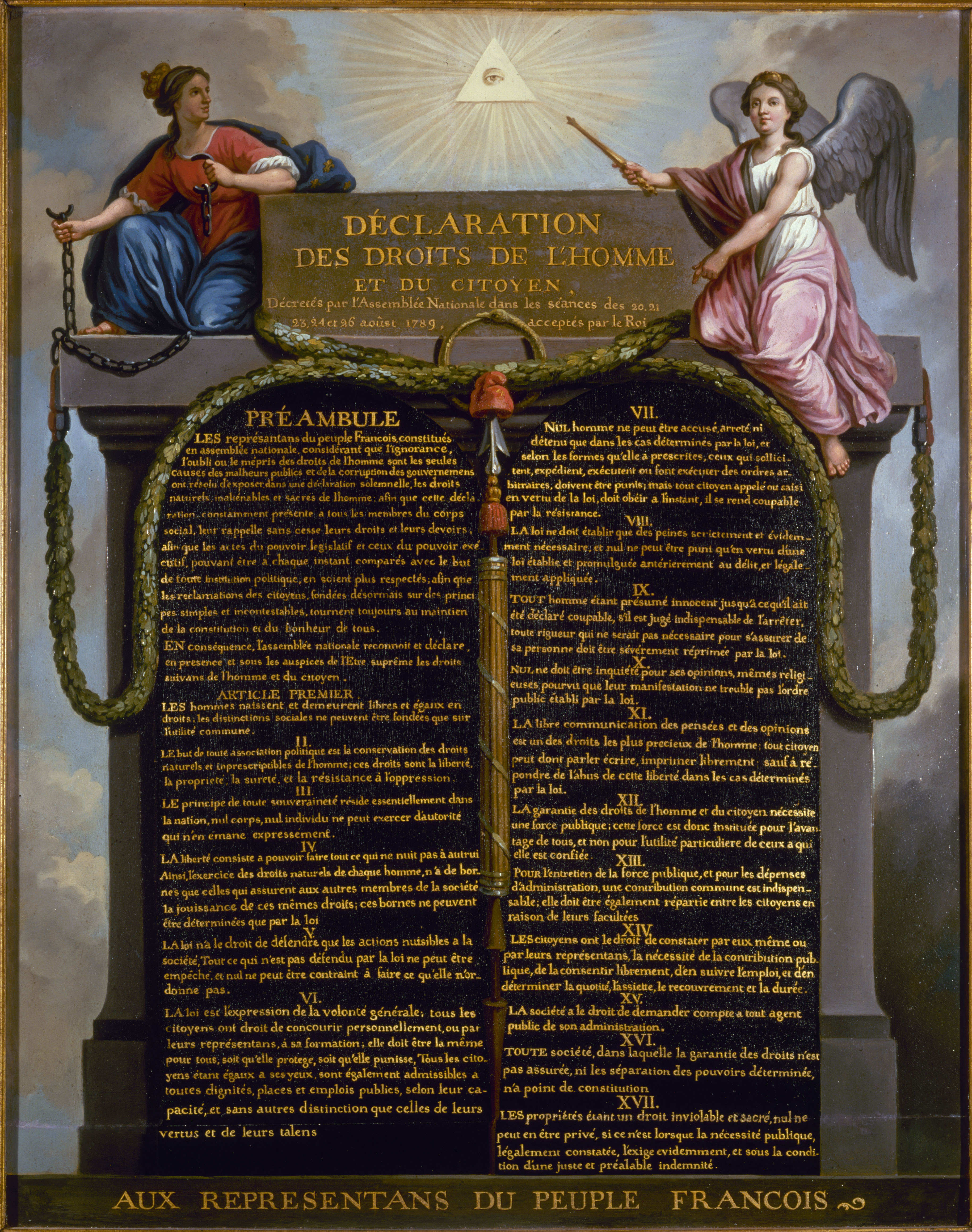

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens.

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens.

"Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen"

in ''The Future of Liberal Democracy: Thomas Jefferson and the Contemporary World'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

and civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Declaration of Human and Civic Rights". Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a significant impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

and democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

in Europe and worldwide places.

The declaration was initially drafted by Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

with assistance from Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, but the majority of the final draft came from Abbé Sieyès

''Abbé'' (from Latin , in turn from Greek , , from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is also the title used for lower-ranki ...

. Influenced by the doctrine of natural right

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' and ...

, human rights are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included at the beginning of the constitutions

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

of both the French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic () was the republican government of France from 27 October 1946 to 4 October 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution of 13 October 1946. Essentially a reestablishment and continuation of the French Third R ...

(1946) and French Fifth Republic

The Fifth Republic () is France's current republic, republican system of government. It was established on 4 October 1958 by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of France, Constitution of the Fifth Republic..

The Fifth Republic emerged fr ...

(1958) and is considered valid as constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in ...

.

History

The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment.Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

prepared the principal drafts in consultation with his close friend Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. In August 1789, Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau

Honoré is a name of French origin and may refer to several people or places:

Given name

Sovereigns of Monaco

Lords of Monaco

*Honoré I, Lord of Monaco, Honoré I of Monaco

Princes of Monaco

*Honoré II, Prince of Monaco, Honoré II of Monaco

...

played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on 26 August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the declaration was discussed by the representatives based on a 24-article draft proposed by , led by The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793

The Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1793 (French: ''Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1793'') is a French political document that preceded that country's first republican constitution. The Declaration ...

, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.

Background

The concepts in the declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of the Enlightenment, such asindividualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, the social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

as theorized by the Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, and the separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights, as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence which preceded it (4 July 1776).

These principles were shared widely throughout European society, rather than being confined to a small elite as in the past. This took different forms, such as ' English coffeehouse culture', and extended to areas colonised by Europeans, particularly British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

. Contacts between diverse groups in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, Paris, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, or Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

were much greater than often appreciated.

Transnational elites who shared ideas and styles were not new; what changed was their extent and the numbers involved. Under Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

was the centre of French culture, fashion and political power. Improvements in education and literacy over the course of the 18th century meant larger audiences for newspapers and journals, with Masonic lodges

A Masonic lodge (also called Freemasons' lodge, or private lodge or constituent lodge) is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry.

It is also a commonly used term for a building where Freemasons meet and hold their meetings. Every new l ...

, coffee houses and reading clubs providing areas where people could debate and discuss ideas. The emergence of this "public sphere

The public sphere () is an area in social relation, social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion, Social influence, influence political action. A "Public" is "of or c ...

" led to Paris replacing Versailles as the cultural and intellectual centre, leaving the Court isolated and less able to influence opinion.

Assisted by Jefferson, then American diplomat to France, Lafayette prepared a draft which echoed some of the provisions of the U.S. declaration. However, there was no consensus on the role of the Crown, and until this question was settled it was impossible to create political institutions. When presented to the legislative committee on 11 July 1789, it was rejected by pragmatists such as Jean Joseph Mounier

Jean Joseph Mounier (; 12 November 1758 – 28 January 1806) was a French politician and judge.

Biography

Mounier was born the son of a cloth merchant in Grenoble in Southeastern France. He studied law, and in 1782 purchased a minor judgeship ...

, President of the Assembly, who feared creating expectations that could not be satisfied.

Conservatives like Gérard de Lally-Tollendal wanted a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate Deliberative assembly, assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate ...

system, with an upper house

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

appointed by the king who would have the right of veto. On 10 September, the majority led by Sieyès and Talleyrand rejected this in favour of a single assembly, while Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

retained only a "suspensive veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

"; this meant he could delay the implementation of a law but not block it. With these questions settled, a new committee was convened to agree on a constitution; the most controversial remaining issue was citizenship

Citizenship is a membership and allegiance to a sovereign state.

Though citizenship is often conflated with nationality in today's English-speaking world, international law does not usually use the term ''citizenship'' to refer to nationalit ...

, itself linked to the debate on the balance between individual rights and obligations. Ultimately, the 1791 Constitution distinguished between active citizens and passive citizens. As a result, it was never fully accepted by radicals in the Jacobin club

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential List of polit ...

.

After editing by Mirabeau, it was published on 26 August as a statement of principle. The final draft contained provisions then considered radical in any European society, let alone France in 1789. French historian Georges Lefebvre argues that combined with the elimination of privilege and feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, it "highlighted equality in a way the (American Declaration of Independence) did not". More importantly, the two differed in intent; Jefferson saw the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

as fixing the political system at a specific point in time, claiming they 'contained no original thought...but expressed the American mind' at that stage. The 1791 French Constitution was viewed as a starting point, the declaration providing an aspirational vision, a key difference between the two revolutions. Attached as a preamble to the French Constitution of 1791

The French Constitution of 1791 () was the first written constitution in France, created after the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the . One of the basic precepts of the French Revolution was adopting constitutionality and establishing po ...

, and that of the 1870 to 1940 French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

, it was incorporated into the current Constitution of France

The current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic , and it replaced the Constitution of the Fourth Republic of 1946 with the exception of the preamble per a 1971 d ...

in 1958.

Summary of principles

The declaration defines a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good." They have certain natural rights to property, toliberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.

When it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

and subversion

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to sabotage the established social order and its structures of Power (philosophy), power, authority, tradition, h ...

. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.

Substance

The declaration is introduced by a preamble describing the fundamental characteristics of the rights, which are qualified as "natural, unalienable and sacred" and "simple and incontestable principles" on which citizens could base their demands. In the second article, "the natural and imprescriptible rights of man" are defined as "liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression". It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end tofeudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

and to exemptions from taxation, freedom, and equal rights for all "Men" and access to public office based on talent. The monarchy was restricted, and all citizens had the right to participate in the legislative process. Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests were outlawed.

The declaration also asserts the principles of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

, in contrast to the divine right of kings that characterized the French monarchy, and social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and social servi ...

among citizens, "All the citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents," eliminating the special rights of the nobility and clergy.

Articles

Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression. Article III – The principle of anysovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will

In political philosophy, the general will () is the will of the people as a whole. The term was made famous by 18th-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It can be considered as an early, informal predecessor to the idea of a social ...

. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disquieted for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Active and passive citizenship

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens.

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens. Active citizenship

Active citizenship involves citizens having control over their daily lives as users of public services, allowing them to influence decisions, voice concerns, and engage with service provision. This includes both choice and voice, enabling citize ...

was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants. This meant that at the time of the declaration, only male property owners held these rights. The deputies in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

believed that only those who held tangible interests in the nation could make informed political decisions. This distinction directly affects articles 6, 12, 14, and 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, as each of these rights is related to the right to vote and to participate actively in the government. With the decree of 29 October 1789, the term active citizen became embedded in French politics.

The concept of passive citizens was created to encompass those populations excluded from political rights in the declaration. Because of the requirements set down for active citizens, the vote was granted to approximately 4.3 million Frenchmen out of a population of around 29 million. These omitted groups included women, the poor, domestic servants, enslaved people, children, and foreigners. As the General Assembly voted upon these measures, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

. This legislation, passed in 1789, was amended by the creators of the Constitution of the Year III

The Constitution of the Year III () was the constitution of the French First Republic that established the Directory. Adopted by the convention on 5 Fructidor Year III (22 August 1795) and approved by plebiscite on 6 September. Its preamble is ...

to eliminate the label of an active citizen. The power to vote was then, however, to be granted solely to substantial property owners.

Tensions arose between active and passive citizens throughout the revolution. This happened when passive citizens started to call for more rights or openly refused to listen to the ideals set forth by active citizens. Women in particular were strong passive citizens who played a significant role in the revolution. Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist. She is best known for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and other writings on women's rights and Abol ...

penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (), also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was written on 14 September 1791 by French activist, Feminism in France, feminist, and playwright Olympe de Gouges in res ...

in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality. By supporting the ideals of the French Revolution and wishing to expand them to women, she represented herself as a revolutionary citizen. Madame Roland

Marie-Jeanne "Manon" Roland de la Platière (Paris, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame RolandOccasionally, she is referred to as Dame Roland. This however is the except ...

also established herself as an influential figure throughout the revolution. She saw women of the French Revolution as holding three roles; "inciting revolutionary action, formulating policy, and informing others of revolutionary events." By working with men, as opposed to working apart from men, she may have been able to further the fight for revolutionary women. As players in the French Revolution, women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political power.

Women's rights

The declaration recognizes many rights as belonging to citizens (who could only be male). This was despite the fact that after theWomen's March on Versailles

The Women's March on Versailles, also known as the Black March, the October Days or simply the March on Versailles, was one of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of ...

on 5 October 1789, women presented the Women's Petition to the National Assembly

The Women's Petition to the National Assembly was produced during the French Revolution and presented to the French National Assembly in November 1789 after The March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, proposing a decree by the National Assembly to ...

in which they proposed a decree giving women equal rights. In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet

Nicolas or Nicolás may refer to:

People Given name

* Nicolas (given name)

Mononym

* Nicolas (footballer, born 1999), Brazilian footballer

* Nicolas (footballer, born 2000), Brazilian footballer

Surname Nicolas

* Dafydd Nicolas (c.1705–1774), ...

and Etta Palm d'Aelders

Etta Lubina Johanna Palm d'Aelders (April 1743 – 28 March 1799), also known as the Baroness of Aelders, was a Dutch spy and feminist, outspoken during the French Revolution. She gave the address ''Discourse on the Injustice of the Laws in F ...

unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women. Condorcet declared "he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth abjured his own". The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

, and this prompted de Gouges to publish her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in September 1791, modeled after the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. It is ironic in the formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

. It states: "This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights, they have lost in society."

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen follows the 17 articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point. Camille Naish has described it as "almost a parody... of the original document". The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility." The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replies: "Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility". De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law, women were fully punishable yet denied equal rights, declaring, "Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker's rostrum".

Slavery

The declaration did not revoke the institution of slavery in the French colonies, as lobbied for by Jacques-Pierre Brissot's '' Les Amis des Noirs'' and opposed by the group of colonial planters called the Club Massiac, because they met at the Hôtel Massiac. Despite the lack of explicit mention of slavery in the declaration, it inspired the slave uprisings inSaint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

in the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

, as discussed in C. L. R. James's history of the Haitian Revolution, '' The Black Jacobins''. In Louisiana, the organizers of the Pointe Coupée Slave Conspiracy of 1795 also drew information from the declaration.

Deplorable conditions for the thousands of enslaved people in Saint-Domingue, the most profitable slave colony in the world, led to the uprisings known as the first successful slave revolt in the New World. Free persons of color were part of the first wave of revolt, but later formerly enslaved people took control. In 1794, the convention was dominated by the Jacobins and abolished slavery, including in the colonies of Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

. However, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

reinstated it in 1802 and attempted to regain control of Saint-Domingue by sending in thousands of troops. After suffering the losses of two-thirds of the men, many to yellow fever, the French withdrew from Saint-Domingue in 1803. Napoleon gave up on North America and agreed to the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

by the United States. In 1804, the leaders of Saint-Domingue declared it an independent state, the Republic of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

, the second republic of the New World. Napoleon abolished the slave trade in 1815. Slavery in France was finally abolished in 1848.

Homosexuality

The vast amount of personal freedom given to citizens by the document created a situation where homosexuality was decriminalized by the French Penal Code of 1791, which covered felonies; the law simply failed to mentionsodomy

Sodomy (), also called buggery in British English, principally refers to either anal sex (but occasionally also oral sex) between people, or any Human sexual activity, sexual activity between a human and another animal (Zoophilia, bestiality). I ...

as a crime, and thus no one could be prosecuted for it. The 1791 Code of Municipal Police did provide misdemeanor penalties for "gross public indecency," which the police could use to punish anyone having sex in public places or otherwise violating social norms. This approach to punishing homosexual conduct was reiterated in the French Penal Code of 1810.

Recognition and legacy

In 2003,UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

added the 1789 version of the declaration (the first printed version) to its Memory of the World International Register, recognising it as documentary heritage of global importance.

See also

*Bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

* Human rights in France

Human rights in France are contained in the preamble of the Constitution of the French Fifth Republic, founded in 1958, and the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. France has also ratified the 1948 Universal Declaration of ...

* Natural person in French law

In French law, a (lit. physical person, English: natural person) is a human being who has capacity as a legal person (').

A is recognized as a subject in law, rather than an object of law such as a thing. A human being with (personhood) i ...

* Rights of Man (1791) by Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

* Universality

Other early declarations of rights

* The decreta of León *Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

* Kouroukan Fouga

* Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish rights known as the Statute of Kalisz, and the Kalisz Privilege, granted Jews in the Middle Ages some protection against discrimination in Poland compared to other places in Europe. These rights included exclusive ...

* Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles (; ; ) were a constitution in the form of a permanent agreement made in 1573 between the "Polish nation" (the szlachta, or nobility, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly-elected Pol ...

and ''Pacta conventa

''Pacta conventa'' (Latin for "articles of agreement") was a contractual agreement entered into between the "Polish nation" (i.e., the szlachta (nobility) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly elected king upon his "free electi ...

''

* Petition of Right

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689. It was part of a wider ...

* Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

* Claim of Right

* Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted in 1776 to proclaim the inherent rights of men, including the right to reform or abolish "inadequate" government. It influenced a number of later documents, including the United States Declaratio ...

* Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights

* Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

* Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of Franchimont

* "Belgian" Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

*

* "Batavian" Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

Citations

General and cited sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Gérard Conac, Marc Debene, Gérard Teboul, eds, ''La Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789; histoire, analyse et commentaires'' , Economica, Paris, 1993, . * McLean, Iain"Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen"

in ''The Future of Liberal Democracy: Thomas Jefferson and the Contemporary World'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

External links

* * {{Authority control 1780s in Paris 1789 documents 1789 events of the French Revolution 1789 in law Age of Enlightenment Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette Government of France History of human rights Human rights in France Human rights instruments Memory of the World Register Political charters Popular sovereignty Works by Thomas Jefferson