Dunkerque-class battleship on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Dunkerque'' class was a pair of

Wary of another naval arms race similar to the Anglo-German race that was seen as contributing to the start of

Wary of another naval arms race similar to the Anglo-German race that was seen as contributing to the start of  The German s, which were armed with a battery of six 283 mm guns, coupled with hesitance on the French Navy's part to commit to small capital ships while Italy still kept its allotted tonnage uncommitted led the French to abandon the 17,500-ton project. New design studies were prepared in 1926–1927, resulting in several proposals in 1928 for a design. These ships were in most respects an enlarged version of the of heavy cruisers then being built. The increase in displacement brought with it a third quadruple 305 mm turret placed aft and heavier armour protection in a version capable of , while a slower ship was to be armed with six guns in twin turrets. Shortages of funding, both for the ships themselves and the necessary improvements to shipyards and harbour facilities to build and operate the vessels ended the proposals. Additionally, political concerns, particularly French efforts to lead disarmament talks in the

The German s, which were armed with a battery of six 283 mm guns, coupled with hesitance on the French Navy's part to commit to small capital ships while Italy still kept its allotted tonnage uncommitted led the French to abandon the 17,500-ton project. New design studies were prepared in 1926–1927, resulting in several proposals in 1928 for a design. These ships were in most respects an enlarged version of the of heavy cruisers then being built. The increase in displacement brought with it a third quadruple 305 mm turret placed aft and heavier armour protection in a version capable of , while a slower ship was to be armed with six guns in twin turrets. Shortages of funding, both for the ships themselves and the necessary improvements to shipyards and harbour facilities to build and operate the vessels ended the proposals. Additionally, political concerns, particularly French efforts to lead disarmament talks in the  Design studies continued after the

Design studies continued after the

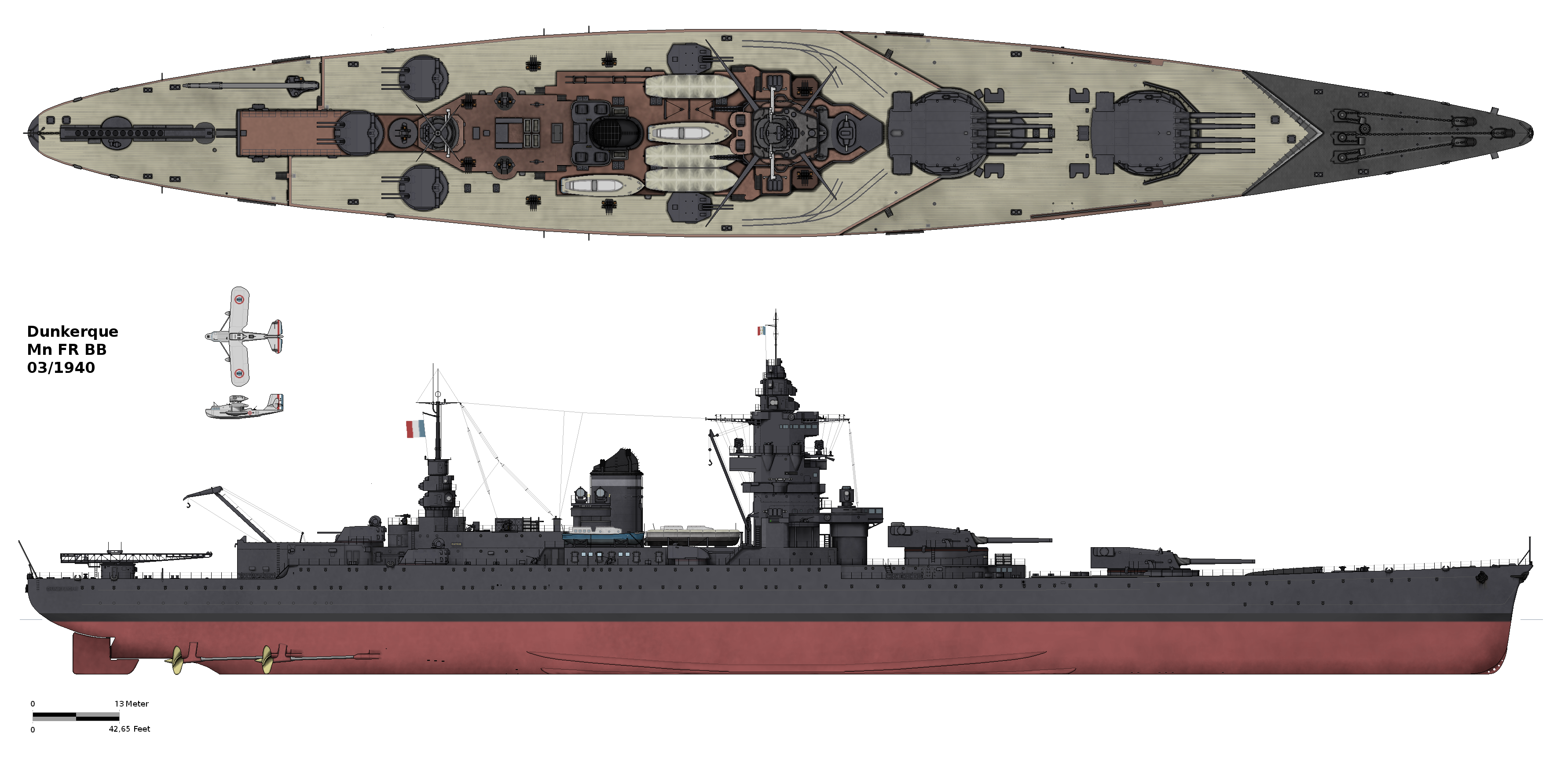

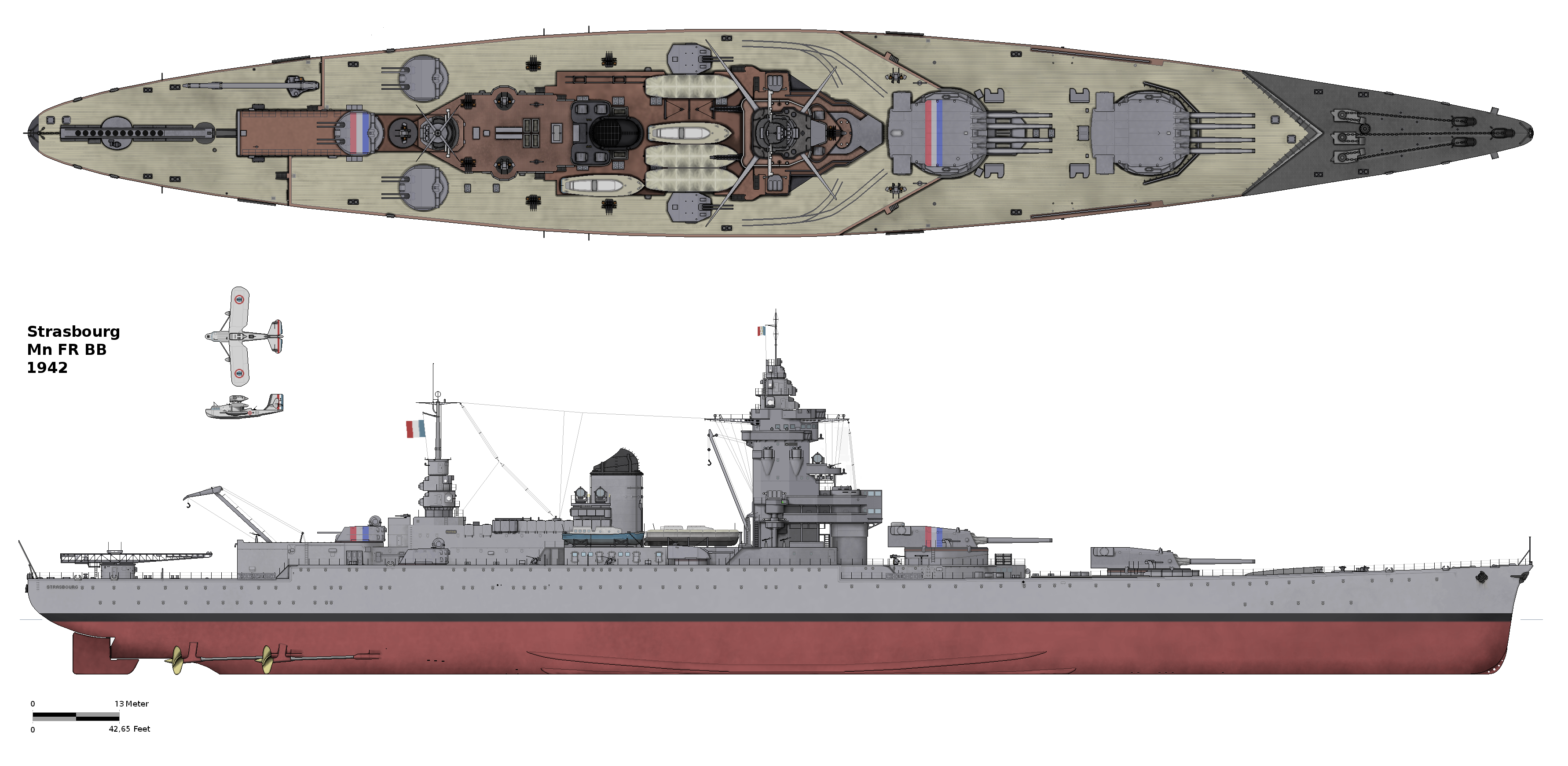

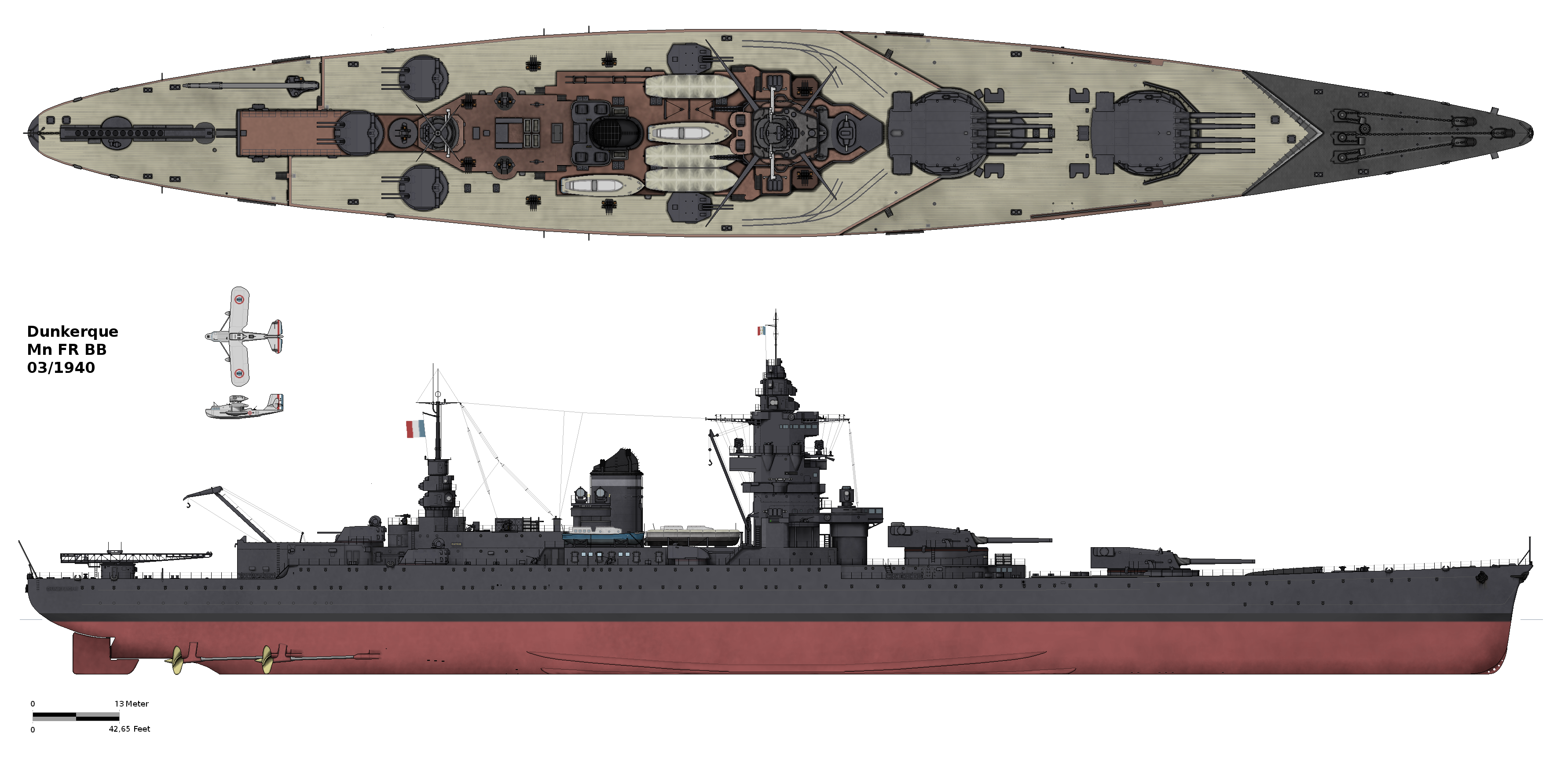

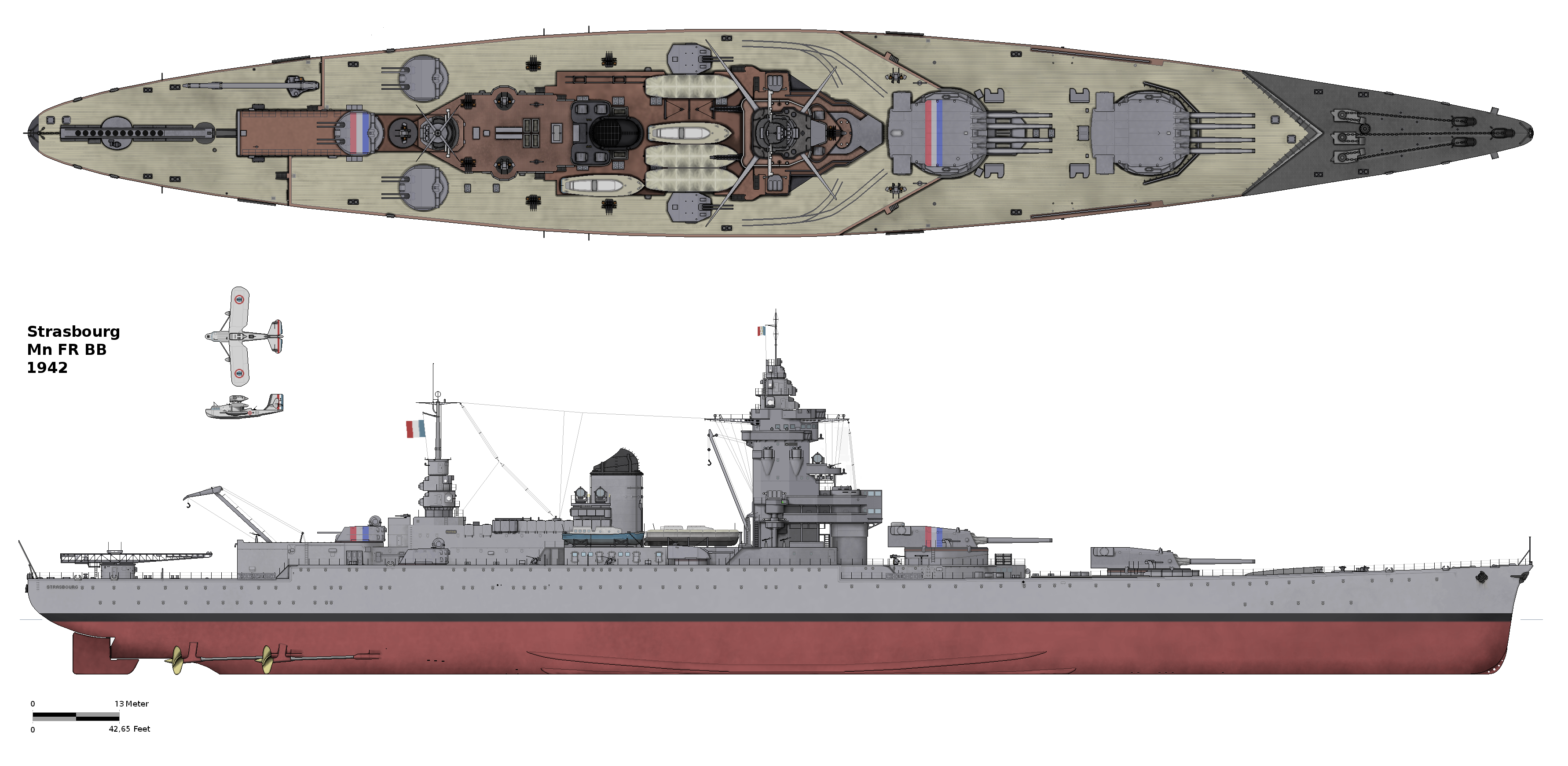

The two ships differed slightly in their dimensions; both were long between perpendiculars, while ''Dunkerque'' was long overall while ''Strasbourg'' was overall. The two ships both had a beam of . ''Dunkerque'' displaced standard, normally, and fully loaded. ''Strasbourg'' was slightly heavier, at standard, normally, and at full load, with the difference being the result of increased armour protection.

The two ships differed slightly in their dimensions; both were long between perpendiculars, while ''Dunkerque'' was long overall while ''Strasbourg'' was overall. The two ships both had a beam of . ''Dunkerque'' displaced standard, normally, and fully loaded. ''Strasbourg'' was slightly heavier, at standard, normally, and at full load, with the difference being the result of increased armour protection.

The ships were powered by four sets of Parsons geared

The ships were powered by four sets of Parsons geared

The ships' protection scheme incorporated the all or nothing principle. Their belt armour was thick amidships for ''Dunkerque'' and for ''Strasbourg'', backed by of

The ships' protection scheme incorporated the all or nothing principle. Their belt armour was thick amidships for ''Dunkerque'' and for ''Strasbourg'', backed by of

After commissioning in 1936, ''Dunkerque'' required extensive testing and evaluation, including extensive trials with her guns, as both the main and secondary battery mounts were new to French naval service. During this period, in May 1937, she represented France at the Naval Review for the

After commissioning in 1936, ''Dunkerque'' required extensive testing and evaluation, including extensive trials with her guns, as both the main and secondary battery mounts were new to French naval service. During this period, in May 1937, she represented France at the Naval Review for the

With the outbreak of war in early September, the ''Force de Raid'', under the command of ''Vice-amiral d'Escadre'' (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, went to sea when reports indicated that the German ''Deutschland''-class cruisers had sortied to attack Allied shipping. The German raiders were still in the

With the outbreak of war in early September, the ''Force de Raid'', under the command of ''Vice-amiral d'Escadre'' (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, went to sea when reports indicated that the German ''Deutschland''-class cruisers had sortied to attack Allied shipping. The German raiders were still in the

The British government, incorrectly fearing that the Germans intended to seize the French fleet and employ it against Britain, embarked on a campaign to neutralise the vessels. The British Force H, which included ''Hood'' and the battleships and , was sent to either compel the French vessels at Mers-el-Kébir to join the

The British government, incorrectly fearing that the Germans intended to seize the French fleet and employ it against Britain, embarked on a campaign to neutralise the vessels. The British Force H, which included ''Hood'' and the battleships and , was sent to either compel the French vessels at Mers-el-Kébir to join the

fast battleship

A fast battleship was a battleship which in concept emphasised speed without undue compromise of either armor or armament. Most of the early World War I-era dreadnought battleships were typically built with low design speeds, so the term "fast ba ...

s built for the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

in the 1930s; the two ships were and . They were the first French battleships built since the of pre-World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

vintage, and they were heavily influenced by the Washington Treaty system that limited naval construction in the 1920s and 1930s. French battleship studies initially focused on countering fast Italian heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

s, leading to early designs for small, relatively lightly protected capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s. But the advent of the powerful German s proved to be more threatening to French interests, prompting the need for larger and more heavily armed and armoured vessels. The final design, completed by 1932, produced a small battleship armed with eight guns that were concentrated in two quadruple gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s forward, with armour sufficient to defeat the ''Deutschland''s guns. ''Strasbourg'' was completed to a slightly modified design, receiving somewhat heavier armour in response to new Italian s. Smaller and less heavily armed and armoured than all other treaty battleships, the ''Dunkerque''s have sometimes been referred to as battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s.

The two ships had relatively short careers; completed just before the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, they served briefly with the Atlantic Squadron in the late 1930s, and ''Dunkerque'' made several visits abroad, including to French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

in 1938 and visits to Britain in 1937 and 1939. With war looming in August 1939, the French created the '' Force de Raid'' (Raiding Force), centred on the two ''Dunkerque''s, which was tasked with hunting down the ''Deutschland''s that were expected to operate in the Atlantic as commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s. The French never caught the German cruisers, and instead the vessels were sent to Mers-el-Kébir to deter Italy from entering the war against France. After Germany defeated France in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

in June 1940, the French were forced to neutralise their fleet, and the two ''Dunkerque''s were to remain inactive at Mers-el-Kébir. Unaware that Germany had no intention of seizing the ships, the British sent Force H to sink the ships; ''Dunkerque'' was damaged in the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir

The attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Battle of Mers-el-Kébir) on 3 July 1940, during the Second World War, was a British naval attack on French Navy ships at the naval base at Mers El Kébir, near Oran, on the coast of French Algeria. The attack was ...

in July, but ''Strasbourg'' escaped to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, where she became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the '' Forces de haute mer'' (High Seas Forces).

''Dunkerque'' was badly damaged in another attack but was temporarily repaired and eventually returned to Toulon for permanent repairs. ''Strasbourg'' saw little activity during this period, as the armistice with Germany limited training operations. ''Dunkerque'' was still in drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

when the Germans launched Case Anton

Case Anton () was the military occupation of Vichy France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severely-limited '' Armisti ...

, occupying the rest of France in November 1942. To prevent the Germans from seizing the ships, the French Navy scuttled the fleet in Toulon. Both ships were badly damaged and were handed over to Italian control, where they were partially broken up. Their hulks, which were bombed by American aircraft in 1944, were eventually sold for scrap in the 1950s.

Background and development

Wary of another naval arms race similar to the Anglo-German race that was seen as contributing to the start of

Wary of another naval arms race similar to the Anglo-German race that was seen as contributing to the start of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the world's major navies held the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

in 1921 to discuss controls on battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

construction, both to limit their size and armament but also to limit the number of ships that could be built. The resulting Washington Naval Treaty limited the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

to of total battleship tonnage; French resistance to a halt on battleship construction, in light of the obsolescent and ''Bretagne''-class battleships that formed the core of its fleet, led to an exception for France (and Italy) to replace worth of battleships during the moratorium, to be laid down in 1927 and 1929. Maximum displacement of any new battleship was restricted to at standard displacement.

In 1926, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, Admiral Henri Salaun, requested a new capital ship design with a displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and physics

*Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

of , intended to counter the new generation of Italian heavy cruisers. The first of these Italian vessels, the two s, were fast and posed a considerable threat to French shipping in the western Mediterranean between metropolitan France and its colonies in French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

. The new French vessel would be armed with a battery of eight guns mounted in two quadruple gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, both arranged forward, since the French envisioned using the ships to chase down the Italian cruisers. The ships would have been armoured to resist the guns of the Italian cruisers, and since the guns were concentrated forward, the amount of armour necessary to protect the ship's vitals allowed significant savings in weight. For the prescribed displacement, four such vessels could be built in the allotted 70,000 tons. The concept was strongly influenced by the British s, which mounted their battery entirely forward to save armour weight.

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, convinced the French government to delay the construction of any new battleships.

Design studies continued after the

Design studies continued after the London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Empire of Japan, Japan, French Third Republic, France, Kingdom of Italy, Italy, and the United Stat ...

, where the British had unsuccessfully pushed for reductions in the maximum displacement and gun calibre. As a show of support for the British position, the French naval command requested designs with a maximum displacement of —the ceiling sought by the British—and a minimum —the maximum displacement that would allow three new ships to be built using the allotted 70,000 tons that France still had available. Apart from the increased size and thicker belt armour, the proposed ship carried the same main battery as the 17,500-ton ship. By this time, Germany had finally begun building the first of the ''Deutschland''s; this led to renewed concerns over the level of armour protection, which was still too thin to defeat the German 283 mm gun. After pressure from the French parliament over the perceived weakness of the design, the Chief of the Naval Staff issued a new set of requirements, including an increase in standard displacement to , an armament of eight 330 mm guns, and armour sufficient to resist 283 mm projectiles.

As refining work on the design progressed, it became apparent that the 25,000-ton standard displacement was too low to accommodate the requested characteristics, so it was increased first to and finally to . Work on the project was completed by early 1932 and it was formally approved on 27 April. The improved armour layout not only rendered the ships immune to 283 mm fire at expected battle ranges, but it was also capable of defeating the 305 mm guns of the older Italian battleships still in service. The first ship, to be named ''Dunkerque'', was ordered on 26 October 1932, with a second projected for the 1934 programme. The Italian announcement in May 1934 that they would begin building new 35,000-ton battleships armed with guns threatened to throw French plans into disarray, since these ships would be vastly superior to the ''Dunkerque'' design, but the first French ship had already been laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

and it was too late to redesign the second vessel, ''Strasbourg'', in response. Side armour for the second ship would be slightly increased while design work began immediately on a 35,000-ton counter to the Italian ships, which produced the .

The ''Dunkerque''-class ships' relatively small size and light armament and emphasis on speed rather than protection, especially compared to the other treaty battleships of the period, has led some to classify them as battlecruisers.

Characteristics

Draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

for ''Dunkerque'' measured normally and increased to at full load, and ''Strasbourg'' drew at normal loading and at full load.

''Dunkerque'' had a crew of 81 officers and 1,300 sailors, while ''Strasbourg''s crew consisted of 32 officers and 1,270 sailors, the additional crew aboard ''Dunkerque'' being an admiral's staff, as she typically operated as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. Each vessel carried a number of smaller boats, including a variety of motor pinnaces, whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the s ...

s, launches, and dinghies

A dinghy is a type of small boat, often carried or Towing, towed by a Watercraft, larger vessel for use as a Ship's tender, tender. Utility dinghies are usually rowboats or have an outboard motor. Some are rigged for sailing but they diffe ...

. Steering was controlled by a single rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

; the rudder had a range of train from 0 to 32 degrees from the centreline, but had a tendency to jam when turned further than 25 degrees. The rudder was electrically operated, but the ships also had manual controls in the event of a power failure.

The ships carried three Loire 130 seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s for use as reconnaissance

In military operations, military reconnaissance () or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, the terrain, and civil activities in the area of operations. In military jargon, reconnai ...

and spotter aircraft on the fantail, and the aircraft facilities consisted of a steam catapult

A catapult is a ballistics, ballistic device used to launch a projectile at a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden rel ...

, a hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

, and a crane to handle the floatplanes. The hangar had two storey

A storey (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English) or story (American English), is any level part of a building with a floor that could be used by people (for living, work, storage, recreation, etc.). Plurals for the wor ...

s and an internal elevator and included workshops to maintain the aircraft while underway. The crane could be folded flat across the deck while not in use.

Machinery

steam turbines

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

driving four 3-bladed screws

A screw is an externally helical threaded fastener capable of being tightened or released by a twisting force (torque) to the screw head, head. The most common uses of screws are to hold objects together and there are many forms for a variety ...

for ''Dunkerque'' and 4-bladed screws for ''Strasbourg''. Steam was provided by six oil-fired water-tube boilers, ducted into a single large funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

. The ''Dunkerque''s adopted the unit system of machinery for their propulsion system, which split the machinery into two separate systems. The arrangement offered improved damage resistance, since one system could be disabled due to battle damage and the other could remain in operation. The ships' boilers were arranged in side-by-side pairs in three boiler rooms; the first was placed below the command tower and the other two were placed below the funnel. The turbines were divided between two engine room

On a ship, the engine room (ER) is the Compartment (ship), compartment where the machinery for marine propulsion is located. The engine room is generally the largest physical compartment of the machinery space. It houses the vessel's prime move ...

s; the first contained the outer shafts and was placed between the boiler rooms, and the inner turbines were placed in an engine room aft of the rear boiler room.

The ships were rated for a top speed of from as designed. On speed tests, ''Dunkerque'' reached a maximum of from , while ''Strasbourg'' made from . Fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

storage amounted to in peacetime but it was reduced to in wartime to prevent the weight of fuel from reducing the armoured freeboard. At a cruising speed of under wartime fuel conditions, the ships had a range of , and at , their cruising radius fell to . The ships' electrical systems were powered by four turbo generator

A turbo generator is an electric generator connected to the shaft of a turbine (water, steam, or gas) for the generation of electric power. Large steam-powered turbo generators provide the majority of the world's electricity and are also u ...

s, with two per engine room, with backup power for critical systems provided by two diesel generator

A diesel generator (DG) (also known as a diesel genset) is the combination of a diesel engine with an electric generator (often an alternator) to generate electrical energy. This is a specific case of an engine generator. A diesel compress ...

s located below the tower. For use while in port, three diesel generators were fitted, and these were located in a separate room below the ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

for the main battery.

Armament

Both ships were armed with eight 330 mm 50- caliber (cal.) guns arranged in two quadruple gun turrets, both of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward of the superstructure. Saint Chamond designed the turrets, which allowed for a maximum elevation to 35 degrees for a maximum range of and depression to -5 degrees. The guns were carried in individual cradles that allowed for limited independent operation, and the guns could be loaded at any angle, though the crews typically returned them to 15 degrees to reduce the likelihood of the shells becoming jammed, a problem that could occur when the guns were at high angles of elevation and other guns in the same turret were fired. To reduce the risk of a single shell hit disabling all four guns, the turrets were divided by an internal bulkhead, and they were spaced apart. The guns fired a shell at amuzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

of ; the shells featured a relatively large bursting charge for their size, reflective of the fact that the ''Dunkerque''s were intended to fight the relatively lightly-armoured ''Deutschland''s. Ammunition storage amounted to 456 shells for the forward turret and 440 shells for the superfiring turret. Their rate of fire was between 1.5 and 2 shots per gun per minute.

The ships' secondary armament consisted of sixteen 45-cal. dual-purpose gun

A dual-purpose gun is a naval artillery mounting designed to engage both surface and air targets.

Description

Second World War-era capital ships had four classes of artillery: the heavy main battery, intended to engage opposing battleships and ...

s; these were mounted in three quadruple and two twin turrets. The quadruple turrets were placed on the stern, with one on the centreline on the superstructure and the other two on either side on the upper deck, and the twin turrets were located amidships, just forward of the funnel. They were the first dual-purpose guns of the French Navy. The guns had range of elevation from -10 to 75 degrees; at 45 degrees, their maximum range was . Their rate of fire was 10 to 12 shells per minute. They were supplied with both armour-piercing (AP) shells for use against warships and high-explosive (HE) shells for use against aircraft. Each gun was allocated approximately 400 shells, a third of which were the AP shells, with the remainder being HE and star shell

A shell, in a modern military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. A shell c ...

s.

Close-range antiaircraft defence was provided by a battery of ten guns in twin mounts for ''Dunkerque'' and eight such guns for ''Strasbourg'', along with thirty-two machine guns in quadruple mounts for ''Dunkerque'' and thirty-six guns for ''Strasbourg''. Two of the 37 mm mounts were placed abreast of the superfiring turret, with the remaining three on the aft superstructure one of which was on the centreline; ''Strasbourg'' omitted the centreline mount, receiving instead another quadruple 13.2 mm gun in its place. Two of the 13.2 mm mounts were located on the upper deck on either side of the command tower, four were arranged around the upper deck further aft, and the remaining two were placed on the aft superstructure.

Fire control

The ships were the first French battleships designed with fire-control directors. The ships carried five directors that each had a stereoscopicrangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

for the main and secondary batteries. For the main guns, one director with a rangefinder was mounted on the tower and a second with an rangefinder on the aft superstructure. Atop the forward director were a pair of directors for the secondary guns, the first with a rangefinder and the top unit with a rangefinder. A third director for the secondary battery was mounted on the roof of the aft main director, also with a 6 m rangefinder. Both main-battery turrets were fitted with their own 12 m rangefinders and the secondary quadruple turrets received 6 m rangefinders for local control in the event the directors were disabled. Fire control equipment for the anti-aircraft battery consisted of four rangefinders, two forward on the tower and two on the aft superstructure. The directors were used to gather range, bearing, and inclination data, which was then sent to a central control station below the armour decks; there, plotting tables and analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as Electrical network, electrical, Mechanics, mechanical, or Hydraulics, hydraulic quantities behaving according to the math ...

s were used to calculate firing solutions for the guns. The guns were remotely controlled via electric motors, but the system proved to be problematic in service, as the training and elevation gears were unreliable, the system that communicated commands from the directors to the guns frequently did not work, and the gunners needed to revert to manual control to make small adjustments. The ships' systems were modified in an attempt to correct these problems, but they never worked reliably.

Armour

teak

Teak (''Tectona grandis'') is a tropical hardwood tree species in the family Lamiaceae. It is a large, deciduous tree that occurs in mixed hardwood forests. ''Tectona grandis'' has small, fragrant white flowers arranged in dense clusters (panic ...

for both ships, extending from the forward 330 mm magazine to the aft 130 mm magazine. The belt was capped on either end by transverse armoured bulkheads; the forward bulkheads were for ''Dunkerque'' and for ''Strasbourg'', and the aft bulkheads were and 210 mm, respectively. It was inclined 11.3 degrees from the vertical to improve its resistance to plunging fire

Plunging fire is a form of indirect fire, where gunfire is fired at a trajectory to make it fall on its target from above. It is normal at the high trajectories used to attain long range, and can be used deliberately to attack a target not susce ...

. The belt extended from about above the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

and below. The armoured box created by the belt and bulkheads was covered by two armour decks, the first of these connected to the top of the belt and was over the forward magazines and reduced to over the propulsion machinery and aft magazines, backed by a steel deck. The lower deck was thick, with sloping sides that connected to the lower edge of the belt; for ''Strasbourg'', the sloped sides were increased to . Aft of the central citadel, the stern was protected by a deck with sloped sides, and additional 50 mm plates covered that portion of the deck that protected the steering gear.

The main-battery turrets were protected by 330 mm of armour plate on the faces, on the sides, and on the roofs, while ''Strasbourg'' received slightly better protection, with faces and roofs. Their rear plates varied between the turrets and between the ships, and were heavy to balance the weight of the guns. For ''Dunkerque'', her forward turret had a rear plate and her superfiring turret had a rear; ''Strasbourg'' had and plates, respectively. The turrets sat atop armoured barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s that were for ''Dunkerque'' and for ''Strasbourg''; both were reduced to 50 mm below the upper deck. Both ships' secondary turrets had faces, sides and roofs, and rears, atop barbettes. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

had thick sides, reduced to on its rear and on the roof. The tower received light protection against aircraft strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such a ...

attacks in the form of plating, while the fire-control directors were protected with steel.

Defence against underwater attacks—torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es and naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s—came in the form of layered torpedo bulkhead

A torpedo bulkhead is a type of naval armor common on the more heavily armored warships, especially battleships and battlecruisers of the early 20th century. It is designed to keep the ship afloat even if the hull is struck underneath the belt ...

s that incorporated liquid-filled voids to absorb blast effects. In addition, a rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

-based compound referred to as ''ébonite mousse'' was used to help absorb the impact and control flooding in critical areas. The underwater protection system covered the same area of the hull as the belt armour. The system included three bulkheads, the first of which was thick, followed by a 10 mm bulkhead, and backed by the main torpedo bulkhead, which was thick. Where it protected the machinery spaces, the system had a depth of almost , compared to the depth of contemporary foreign ships, which was typically around . Where the system had to be narrowed, abreast the forward and aft magazines, the main bulkhead increased in thickness to 40 and then 50 mm to account for the reduction in effectiveness. To prevent the explosion of a mine below the hull from breaching the ammunition magazines, the bottoms of the magazines were raised above the double bottom, and they were protected by 30 mm plates.

Modifications

The ships received relatively minor modifications in their short careers; both ships received a funnel cap to reduce smoke interference with the command tower in 1938. After the start ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the 12 m rangefinder for the forward main battery director was replaced with a version aboard ''Dunkerque'', while ''Strasbourg'' did not receive an updated rangefinder. A degaussing

Degaussing, or deperming, is the process of decreasing or eliminating a remnant magnetic field. It is named after the gauss, a unit of magnetism, which in turn was named after Carl Friedrich Gauss. Due to magnetic hysteresis, it is generally not ...

cable was fitted to ''Strasbourg'' to reduce the risk of detonating German magnetic mines during a refit from November 1939 to January 1940, and during another refit in August–September, a steel screen was erected to protect the light anti-aircraft guns from strafing attacks. ''Strasbourg'' had her command tower modified in November and December 1940 to refit her for use as a flagship, as ''Dunkerque'' had been disabled by that point. While ''Dunkerque'' was under repair at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

in 1942, consideration was given to replacing her aviation facilities with additional 37 mm guns to improve her anti-aircraft defences, but this work was not begun before the fleet was scuttled in November. During another refit from January to April 1942, ''Strasbourg''s forward 37 mm mounts were moved from her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

to the weather deck, as they were on ''Dunkerque'', and she received an air-search radar set with four antennae. Early tests with the set indicated a detection range of .

Ships

Service history

After commissioning in 1936, ''Dunkerque'' required extensive testing and evaluation, including extensive trials with her guns, as both the main and secondary battery mounts were new to French naval service. During this period, in May 1937, she represented France at the Naval Review for the

After commissioning in 1936, ''Dunkerque'' required extensive testing and evaluation, including extensive trials with her guns, as both the main and secondary battery mounts were new to French naval service. During this period, in May 1937, she represented France at the Naval Review for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Elizabeth, as King of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realm, ...

. In early 1938, ''Dunkerque'' toured France's West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

n colonies and islands in the Caribbean. After finally being pronounced ready for active service in September, she became the flagship of the Atlantic Squadron. Shortly thereafter, ''Strasbourg'' was commissioned to begin working up, but the increasingly unstable international situation in Europe forced the French to rush the ship through trials; ''Strasbourg'' got little more than six months of testing and training before entering service, compared to more than two years for ''Dunkerque''.

During the Sudetenland Crisis with Germany in early April 1939, ''Dunkerque'' was sent to cover the return of the training cruiser as it returned from a cruise in the Caribbean, as a nearby German squadron would have threatened the vessel if war had broken out. ''Strasbourg'' then joined the squadron and the two ships were designated the 1st Battle Division. The ships visited Portugal in May before embarking on a lengthy tour of Britain later that month and in June. Both vessels conducted extensive training exercises off Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

in July and August as Europe drifted toward war. As tensions rose with Germany over the latter's aggressive demands on Polish territory, the British and French naval commands agreed to divide responsibilities for joint operations in the anticipated war; France would cover Allied shipping in the central Atlantic, and for this purpose, ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' were assigned to the new '' Force de Raid'' (Raiding Force) to hunt down German commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s.

World War II

With the outbreak of war in early September, the ''Force de Raid'', under the command of ''Vice-amiral d'Escadre'' (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, went to sea when reports indicated that the German ''Deutschland''-class cruisers had sortied to attack Allied shipping. The German raiders were still in the

With the outbreak of war in early September, the ''Force de Raid'', under the command of ''Vice-amiral d'Escadre'' (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, went to sea when reports indicated that the German ''Deutschland''-class cruisers had sortied to attack Allied shipping. The German raiders were still in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, however, and so after meeting a French passenger liner

A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. The category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited numbers of passengers, such as the ubiquitous twelve-passenger freig ...

, the ''Force de Raid'' returned to port. The unit was then split to increase the chances of finding the German cruisers, with ''Dunkerque'' operating out of Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

, with the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

while ''Strasbourg'' moved south to Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

in French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

in company with the British carrier . In November, ''Dunkerque'' joined the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

to hunt for the German battleships and , but they were unable to locate the German vessels.

In late November, ''Strasbourg'' was recalled from Dakar and the ''Force de Raid'' was reconstituted. ''Dunkerque'' carried a shipment of part of the Banque de France

The Bank of France ( ) is the national central bank for France within the Eurosystem. It was the French central bank between 1800 and 1998, issuing the French franc. It does not translate its name to English, and thus calls itself ''Banque de ...

's gold reserve to Canada and then escorted a troop ship convoy to Britain in December. The ships were sent to the Mediterranean in early 1940 as the threat of war with Italy increased; the French hoped to use the show of force

A show of force is a military operation intended to warn (such as a warning shot) or to intimidate an opponent by showcasing a capability or will to act if one is provoked. Shows of force may also be executed by police forces and other armed, n ...

to deter Italy from entering the war. Consideration was given to sending them to support the Norwegian Campaign in April 1940, but Italy's increasingly hostile posture forced the French to keep them in the Mediterranean. Based in Mers-el-Kébir along with other elements of the French fleet, the ships saw little activity during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

that ended with French defeat; the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

mandated that the French fleet would be demilitarised, with ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' to remain in Mers-el-Kébir.

Mers-el-Kébir

The British government, incorrectly fearing that the Germans intended to seize the French fleet and employ it against Britain, embarked on a campaign to neutralise the vessels. The British Force H, which included ''Hood'' and the battleships and , was sent to either compel the French vessels at Mers-el-Kébir to join the

The British government, incorrectly fearing that the Germans intended to seize the French fleet and employ it against Britain, embarked on a campaign to neutralise the vessels. The British Force H, which included ''Hood'' and the battleships and , was sent to either compel the French vessels at Mers-el-Kébir to join the Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army ( ; AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (; FFL) during World War II. The military force of Free France, it participated ...

, be demilitarised in France's Caribbean colonies or the United States, or to sink them. After Gensoul rejected their demands, the British opened fire. The French ships were moored with their sterns toward the sea, which initially prevented ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' from returning fire until they could get underway. The guns of the British ships quickly inflicted serious damage on ''Dunkerque'' and the old battleships and . ''Dunkerque''s crew was forced to beach her to prevent her from sinking; ''Bretagne'' exploded and ''Provence'' sank to the harbour bottom. ''Strasbourg'', however, was able to slip her moorings and escape from the harbour in the confusion. Escorted by four destroyers, she avoided the British fleet and escaped to Toulon.

Repair work began almost immediately on ''Dunkerque'', with a view toward restoring the ship to seaworthy condition so she could be returned to Toulon for drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

ing and permanent repairs. Upon learning that the ship had not been permanently disabled, the British returned and launched an air strike from the carrier , for which Gensoul and ''Dunkerque''s commanders had failed to erect defences, either in the form of torpedo nets or manned anti-aircraft guns. The Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a retired biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was a ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the World War I, First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carryin ...

s failed to score any direct hits on ''Dunkerque'', but a pair of torpedoes struck the patrol boat ''Terre-Neuve'' that had been moored alongside the ship. Those hits led to a secondary explosion of that vessel's depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon designed to destroy submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited ...

s that amounted to an equivalent of eight aerial torpedoes, which caused extensive damage to ''Dunkerque''s hull. Nevertheless, repair work quickly resumed, and her holed hull was plated over and pumped dry.

In the meantime, ''Strasbourg'' became the flagship of the '' Forces de haute mer'', which was created from the remains of the French fleet still available in Toulon, under the command of '' Amiral'' Jean de Laborde

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jean ...

. During this period, limitations on French naval activity from the armistice kept ''Strasbourg'' largely in port, limited to two training cruises per month. In September 1940, the ship and several cruisers sortied to cover ''Provence'', which had been repaired and refloated after the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, as she returned to Toulon.

By April 1941, ''Dunkerque'' was back in a seaworthy condition, though tests of her propulsion system were necessary before she would be able to get underway. Heavy fighting between British and Italian forces during the Mediterranean Campaign delayed ''Dunkerque''s return to France until February 1942. Escorted by five destroyers and some 65 aircraft, she arrived in Toulon on 20 February and was later drydocked there in June to begin repairs.

Scuttling at Toulon

FollowingOperation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of French North Africa on 8 November, Germany launched Case Anton

Case Anton () was the military occupation of Vichy France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severely-limited '' Armisti ...

in retaliation, moving to seize all of the so-called "Zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered b ...

", the part of Vichy France that had up to that point remained unoccupied. Expecting the Germans to arrive to commandeer the ships, de Laborde ordered his crews to prepare to scuttle their ships. When the Germans arrived in Toulon on 27 November, the work had been completed and de Laborde issued the order. Sabotage teams went through the ships, destroying any equipment that might be usable by the Germans, including rangefinders, gyrocompass

A gyrocompass is a type of non-magnetic compass which is based on a fast-spinning disc and the rotation of the Earth (or another planetary body if used elsewhere in the universe) to find geographical Direction (geometry), direction automaticall ...

es, and radios. They lit fires in the boilers and shut off the water supply so that the boilers would overheat and explode, and they packed gun barrels with explosives. ''Strasbourg''s crew then opened the seacocks and detonated scuttling charges to ensure the ship sank. ''Dunkerque'' was at that time still incomplete in the drydock, so she was set on fire, damaged by demolition charges, and then flooded in the drydock when the locks were opened.

Italy received control over most of the wrecks, as Germany had little interest; the Italian fleet sought as many vessels as possible, but ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' were too badly damaged to be repaired quickly, and so they wrote them off as a total loss. To prevent the French from repairing them in the future, the Italians inflicted further damage on the wrecks, including cutting their main-battery guns. They then began breaking up both vessels, but after the Italian surrender in September 1943, the Germans reasserted control over the port. The Germans then turned ''Strasbourg'' back to Vichy control, who placed the ship in a state of conservation in the Bay of Lazaret, hoping to repair the ship after the war. She was then bombed and sunk again by American aircraft after Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil), known as Débarquement de Provence in French ("Provence Landing"), was the code name for the landing operation of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15Augu ...

, the Allied invasion of southern France. ''Dunkerque'' was also bombed several times in the final years of the war.

After falling under Free French control in October 1944, ''Strasbourg'' was raised again but by that point was beyond repairing. Instead, she was retained as a target for underwater weapons tests. Little else was done with either wreck for more than a decade; in March 1955, ''Strasbourg'' was condemned and renamed ''Q45'' before being sold for scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

in May. ''Dunkerque'' became ''Q56'' in September but remained extant until September 1958, when she, too, was sold to ship breakers.

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dunkerque Class Battleship Battleship classes Battlecruiser classes World War II battleships of France Ship classes of the French Navy