Demon core on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The demon core was a sphere of

The demon core was a sphere of

On May 21, 1946, physicist Louis Slotin and seven other personnel were in a Los Alamos laboratory conducting another experiment to verify the closeness of the core to criticality by the positioning of neutron reflectors. Slotin, who was leaving Los Alamos, was showing the technique to Alvin C. Graves, who would use it in a final test before the

On May 21, 1946, physicist Louis Slotin and seven other personnel were in a Los Alamos laboratory conducting another experiment to verify the closeness of the core to criticality by the positioning of neutron reflectors. Slotin, who was leaving Los Alamos, was showing the technique to Alvin C. Graves, who would use it in a final test before the

The demon core was a sphere of

The demon core was a sphere of plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

that was involved in two fatal radiation accidents when scientists tested it as a fissile core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (laboratory), a highly specialized shared research resource

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber ...

of an early atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. It was manufactured in 1945 by the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, the U.S. nuclear weapon development effort during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It was a subcritical mass that weighed and was in diameter. The core was prepared for shipment to the Pacific Theater as part of the third nuclear weapon to be dropped on Japan, but when Japan surrendered, the core was retained for testing and potential later use in the case of another conflict.

The two criticality accident

A criticality accident is an accidental uncontrolled nuclear fission chain reaction. It is sometimes referred to as a critical excursion, critical power excursion, divergent chain reaction, or simply critical. Any such event involves the uninten ...

s occurred at the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

in New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

on August 21, 1945, and May 21, 1946. In both cases, an experiment was intended to demonstrate how close the core was to criticality, using a neutron-reflective tamper (layer of dense material surrounding the fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy i ...

). In both accidents, the core was accidentally put into a critical configuration. Physicists Harry Daghlian (in the first accident) and Louis Slotin (in the second accident) both suffered acute radiation syndrome

Acute radiation syndrome (ARS), also known as radiation sickness or radiation poisoning, is a collection of health effects that are caused by being exposed to high amounts of ionizing radiation in a short period of time. Symptoms can start wit ...

and died shortly afterward. At the same time, others present in the laboratory were also exposed. The core was melted down during the summer of 1946, and the material was recycled for use in other cores.

Manufacturing and early history

The demon core (like the core used in the bombing of Nagasaki) was, when assembled, a solid softball-sized sphere measuring in diameter. It consisted of three parts made of plutonium-gallium: two hemispheres and an anti-jet ring, designed to keepneutron flux

The neutron flux is a scalar quantity used in nuclear physics and nuclear reactor physics. It is the total distance travelled by all free neutrons per unit time and volume. Equivalently, it can be defined as the number of neutrons travelling ...

from "jetting" out of the joined surface between the hemispheres during implosion. The core of the device used in the Trinity Test

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range in July did not have such a ring.

The refined plutonium was shipped from the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It has also been known as SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear R ...

in Washington to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

; an inventory document dated August 30 shows Los Alamos had expended "HS-1, 2, 3, 4; R-1" (the components of the Trinity and Nagasaki bombs) and had in its possession "HS-5, 6; R-2", finished and in the hands of quality control. Material for "HS-7, R-3" was in the Los Alamos metallurgy section and would also be ready by September 5 (it is not certain whether this date allowed for the unmentioned "HS-8s fabrication to complete the fourth core). The metallurgists used a plutonium-gallium alloy, which stabilized the delta () phase allotrope of plutonium so it could be hot pressed into the desired spherical shape. As plutonium was found to corrode readily, the sphere was then coated with nickel.

On August 10, Major General Leslie R. Groves Jr., wrote to General of the Army George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, to inform him that:

Marshall added an annotation, "It is not to be released on Japan without express authority from the President", on President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

's orders. On August 13, the third bomb was scheduled. It was anticipated that it would be ready by August 16 to be dropped on August 19. This was pre-empted by Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, while preparations were still being made for it to be couriered to Kirtland Field. The third core remained at Los Alamos.

First incident

The core, once assembled, was designed to be at "−5 cents". In this state, there is only a small safety margin against extraneous factors that might increase reactivity, causing the core to become supercritical, and then prompt critical, a brief state of rapid energy increase. These factors are not common in the environment; they are only likely to occur under conditions such as the compression of the solid metallic core (which would eventually be the method used to explode the bomb), the addition of more nuclear material, or provision of an external reflector which would reflect outboundneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s back into the core. The experiments conducted at Los Alamos leading to the two fatal accidents were designed to guarantee that the core was indeed close to the critical point by arranging such reflectors and seeing how much neutron reflection was required to approach supercriticality.

On August 21, 1945, the plutonium core produced a burst of neutron radiation

Neutron radiation is a form of ionizing radiation that presents as free neutrons. Typical phenomena are nuclear fission or nuclear fusion causing the release of free neutrons, which then react with nuclei of other atoms to form new nuclides— ...

that resulted in physicist Harry Daghlian's death. Daghlian made a mistake while performing neutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, tungsten carbide, gold, or other materials. A neutron reflect ...

experiments on the core. He was working alone; a security guard, Private Robert J. Hemmerly, was seated at a desk away. The core was placed within a stack of neutron-reflective tungsten carbide

Tungsten carbide (chemical formula: ) is a carbide containing equal parts of tungsten and carbon atoms. In its most basic form, tungsten carbide is a fine gray powder, but it can be pressed and formed into shapes through sintering for use in in ...

bricks, and the addition of each brick made the assembly closer to criticality. While attempting to stack another brick around the assembly, Daghlian accidentally dropped it onto the core and thereby caused the core to go well into supercriticality, a self-sustaining critical chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events.

Chain reactions are one way that sys ...

. Following criticality, a bright blue light flashed throughout the room. He quickly moved the brick off the assembly, but he received a fatal dose of radiation. He died 25 days later from acute radiation poisoning.

Second incident

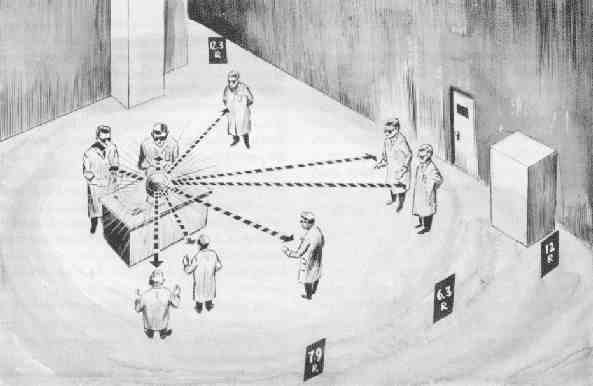

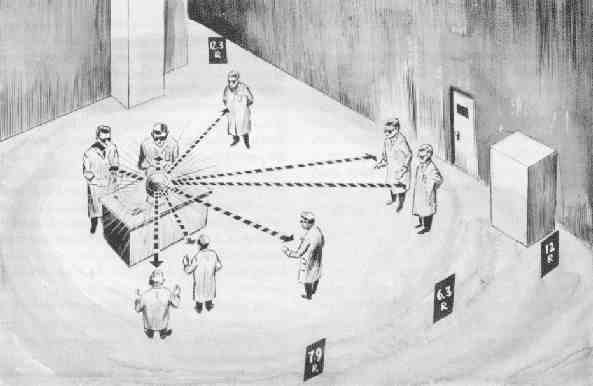

On May 21, 1946, physicist Louis Slotin and seven other personnel were in a Los Alamos laboratory conducting another experiment to verify the closeness of the core to criticality by the positioning of neutron reflectors. Slotin, who was leaving Los Alamos, was showing the technique to Alvin C. Graves, who would use it in a final test before the

On May 21, 1946, physicist Louis Slotin and seven other personnel were in a Los Alamos laboratory conducting another experiment to verify the closeness of the core to criticality by the positioning of neutron reflectors. Slotin, who was leaving Los Alamos, was showing the technique to Alvin C. Graves, who would use it in a final test before the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity on July 16, 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices sinc ...

nuclear tests scheduled a month later at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese language, Marshallese: , , ), known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 19th century and 1946, is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. The atoll is at the no ...

. It required the operator to place two half-spheres of beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, hard, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with ...

(a neutron reflector) around the core to be tested and manually lower the top reflector over the core using a thumb hole at the polar point. As the reflectors were manually moved closer and farther away from each other, neutron detectors indicated the core's neutron multiplication rate. The experimenter needed to maintain a slight separation between the reflector halves to allow enough neutrons to escape from the core in order to stay below criticality. The standard protocol was to use shims between the halves, as allowing them to close completely could result in the instantaneous formation of a critical mass and a lethal power excursion.

By Slotin's own unapproved protocol, the shims were not used. The top half of the reflector was resting directly on the bottom half at one point, while 180 degrees from this point a gap was maintained by the blade of a flat-tipped screwdriver

A screwdriver is a tool, manual or powered, used for turning screws.

Description

A typical simple screwdriver has a handle and a shaft, ending in a tip the user puts into the screw head before turning the handle. This form of the screwdriver ...

in Slotin's hand. The size of the gap between the reflectors was changed by twisting the screwdriver. Slotin, who was given to bravado, became the local expert, performing the test on almost a dozen occasions, often in his trademark blue jeans and cowboy boots in front of a roomful of observers. Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

reportedly told Slotin and others they would be "dead within a year" if they continued performing the test in that manner. Scientists referred to this flirtation with a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

as "tickling the dragon's tail", based on a remark by physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

.

On the day of the accident, Slotin's screwdriver slipped outward a fraction of an inch while he was lowering the top reflector, allowing the reflector to fall into place around the core. Instantly, there was a flash of light; the core had become supercritical, releasing an intense burst of neutron radiation. Slotin quickly twisted his wrist, flipping the top shell to the floor. There was an estimated half-second between when the sphere closed to when Slotin removed the top reflector. Slotin received a lethal dose of neutron and gamma radiation in less than a second, while the position of Slotin's body over the apparatus shielded the others from much of the neutron radiation. Slotin died nine days later from acute radiation poisoning.

Graves, the next nearest person to the core, was watching over Slotin's shoulder and was thus partially shielded by him. He received a high but non-lethal radiation dose

Ionizing (ionising) radiation, including nuclear radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionize atoms or molecules by detaching electrons from them. Some pa ...

. Graves was hospitalized for several weeks with severe radiation poisoning. He died 19 years later, at age 55, of heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

. While this may have been caused by Graves' exposure to radiation, the condition may have been hereditary, as his father also died of heart failure.

The second accident was reported by the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

on May 26, 1946: "Four men injured through accidental exposure to radiation in the government's atomic laboratory here os Alamoshave been discharged from the hospital and 'immediate condition' of four others is satisfactory, the Army reported today. Dr. Norris E. Bradbury, project director, said the men were injured last Tuesday in what he described as an experiment with fissionable material."

Medical studies

Later research was performed concerning the health of the men. An early report was published in 1951. A later report was compiled for the U.S. government and submitted in 1979. A summary of its findings: Two machinists, Paul Long and another, unidentified, in another part of the building, away, were not treated. After these incidents, the core, originally known as "Rufus", was referred to as the "demon core". Hands-on criticality experiments were stopped, and remote-control machines and TV cameras were designed by Schreiber, one of the survivors, to perform such experiments with all personnel at a quarter-mile distance.Planned uses and fate of the core

The demon core was intended for use in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests, but after the second criticality accident, time was needed for its radioactivity to decrease and for it to be re-evaluated for the effects of the fission products it held, some of which were veryneutron poison

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable ef ...

ous to the desired level of fission. The next two cores were shipped for use in ''Able'' and ''Baker'', and the demon core was scheduled to be shipped later for the third test of the series, provisionally named ''Charlie'', but that test was canceled because of the unexpected level of radioactivity resulting from the underwater ''Baker'' test and the inability to decontaminate the target warships. The core was melted down during the summer of 1946, and the material was recycled for use in other cores.

See also

* Cecil Kelley criticality accidentReferences

External links

* {{Portal bar, History of Science, Nuclear technology, Physics Nuclear weapons Plutonium Nuclear weapons program of the United States Nuclear accidents and incidents in the United States History of the Manhattan Project Former objects