Coppermine Expedition Of 1819–1822 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Coppermine expedition of 1819–1822 was a British overland undertaking to survey and chart the area from

The Coppermine expedition of 1819–1822 was a British overland undertaking to survey and chart the area from

In the years following the

In the years following the

Without tents, they were grateful for snowfall, as it provided an extra layer of insulation over their blankets. Franklin later wrote that the journey brought "a great inter-mixture of agreeable and disagreeable circumstances. Could the amount of each be balanced, I suspect the latter would much preponderate."

The advance party arrived at Fort Chipewyan in late March, having covered in six weeks. Once there, Franklin found equipping his expedition far more difficult than had been anticipated. The harsh winter meant that food was barely available, and he had to make do with a vague promise that hunters would feed them en route, and that the chief of the Coppermine First Nations would offer assistance.

The best voyageurs were preoccupied with the conflict between the two fur trading companies, or unwilling to risk a journey into unknown terrain, far outside their normal range and with uncertain supplies. Eventually, Franklin was able to recruit a team of 16 voyageurs, but most of the men fell well below the standard he desired.

Without tents, they were grateful for snowfall, as it provided an extra layer of insulation over their blankets. Franklin later wrote that the journey brought "a great inter-mixture of agreeable and disagreeable circumstances. Could the amount of each be balanced, I suspect the latter would much preponderate."

The advance party arrived at Fort Chipewyan in late March, having covered in six weeks. Once there, Franklin found equipping his expedition far more difficult than had been anticipated. The harsh winter meant that food was barely available, and he had to make do with a vague promise that hunters would feed them en route, and that the chief of the Coppermine First Nations would offer assistance.

The best voyageurs were preoccupied with the conflict between the two fur trading companies, or unwilling to risk a journey into unknown terrain, far outside their normal range and with uncertain supplies. Eventually, Franklin was able to recruit a team of 16 voyageurs, but most of the men fell well below the standard he desired.

Reunited with Hood and Richardson, the party left for Great Slave Lake in July, reaching the trading post at

Reunited with Hood and Richardson, the party left for Great Slave Lake in July, reaching the trading post at

The expedition's second winter was another difficult one. Supplies arrived only intermittently; the rival companies each preferring to let the other provide them. Ammunition ran short, and the First Nations hunters were less effective than had been hoped. Finally, with the party at risk of starvation, Back was sent back to Fort Providence to browbeat the companies into action. After a journey on snowshoes, often with no shelter beyond blankets and a deerskin in temperatures as low as , Back returned having secured enough supplies to meet the expedition's immediate needs.

The expedition's second winter was another difficult one. Supplies arrived only intermittently; the rival companies each preferring to let the other provide them. Ammunition ran short, and the First Nations hunters were less effective than had been hoped. Finally, with the party at risk of starvation, Back was sent back to Fort Providence to browbeat the companies into action. After a journey on snowshoes, often with no shelter beyond blankets and a deerskin in temperatures as low as , Back returned having secured enough supplies to meet the expedition's immediate needs.

There was also continuing unrest in the camp. The voyageurs, led by the two interpreters Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, rebelled. Franklin's threats were ineffective; St. Germain and Adam insisting that as continuing into the wilderness would mean certain death, the threat of execution for mutiny was laughable. Negotiation by Willard Wentzel, the North West Company's representative, eventually restored an uneasy truce. The discord was not confined to the voyageurs; Back and Hood had fallen out over their rivalry for the affections of a Yellowknives girl nicknamed Greenstockings, and would have fought a duel with pistols over her had John Hepburn not removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation was defused when Back was dispatched south. Hood subsequently fathered a child with Greenstockings.

The winter of 1820–21 passed, and Franklin set out again on 4 June 1821. His plans for the coming summer were vague; he had decided to explore east from the mouth of the Coppermine in the hope of either meeting William Edward Parry or reaching Repulse Bay, where he might obtain adequate supplies from local Inuit to allow him to return directly to York Factory by way of Hudson Bay. However, if Parry failed to appear, or he was unable to reach Repulse Bay he would either retrace his outward route or, if it seemed better, return directly to Fort Enterprise across the uncharted Barren Lands to the east of the Coppermine River.

There was also continuing unrest in the camp. The voyageurs, led by the two interpreters Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, rebelled. Franklin's threats were ineffective; St. Germain and Adam insisting that as continuing into the wilderness would mean certain death, the threat of execution for mutiny was laughable. Negotiation by Willard Wentzel, the North West Company's representative, eventually restored an uneasy truce. The discord was not confined to the voyageurs; Back and Hood had fallen out over their rivalry for the affections of a Yellowknives girl nicknamed Greenstockings, and would have fought a duel with pistols over her had John Hepburn not removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation was defused when Back was dispatched south. Hood subsequently fathered a child with Greenstockings.

The winter of 1820–21 passed, and Franklin set out again on 4 June 1821. His plans for the coming summer were vague; he had decided to explore east from the mouth of the Coppermine in the hope of either meeting William Edward Parry or reaching Repulse Bay, where he might obtain adequate supplies from local Inuit to allow him to return directly to York Factory by way of Hudson Bay. However, if Parry failed to appear, or he was unable to reach Repulse Bay he would either retrace his outward route or, if it seemed better, return directly to Fort Enterprise across the uncharted Barren Lands to the east of the Coppermine River.

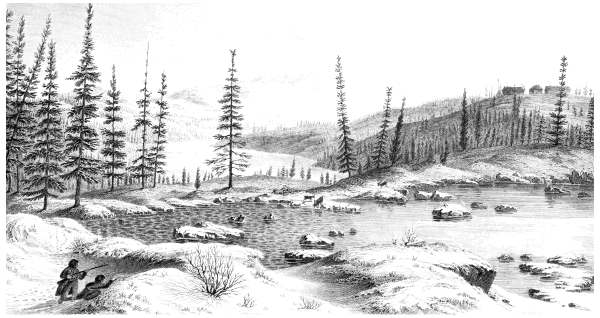

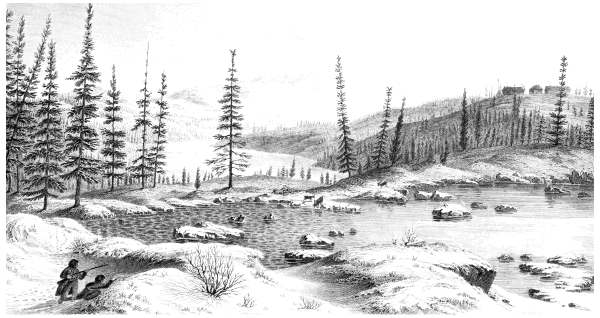

The journey down the Coppermine River took far longer than planned, and Franklin quickly lost faith in his First Nations guides, who in fact knew the area little better than he did, and assured him that the sea was close, then far, then close again. The ice on the rivers and lakes was still firm, and for the first of the journey the canoes had to be dragged on

The journey down the Coppermine River took far longer than planned, and Franklin quickly lost faith in his First Nations guides, who in fact knew the area little better than he did, and assured him that the sea was close, then far, then close again. The ice on the rivers and lakes was still firm, and for the first of the journey the canoes had to be dragged on

Their going across the Barren Lands was extremely arduous; the ground was a treacherous expanse of sharp rocks that cut their boots and feet, and was a constant threat to more serious injury. Richardson remarked "if anyone had broken a limb here his fate would have been melancholy indeed, as we could neither have remained with him, nor carried him on with us". The canoes proved difficult to carry and were dropped by the voyageurs—Franklin suspected deliberately—and became completely unusable.

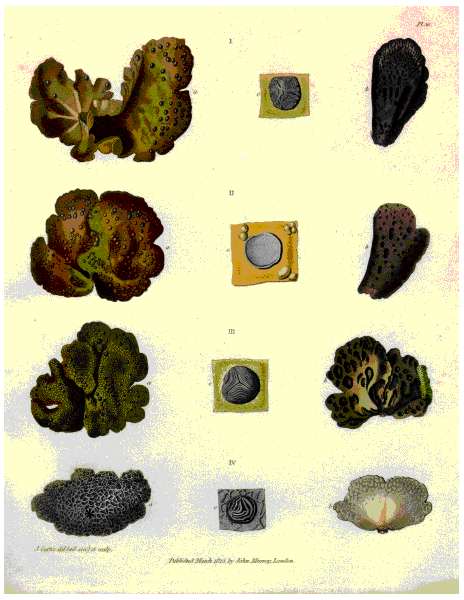

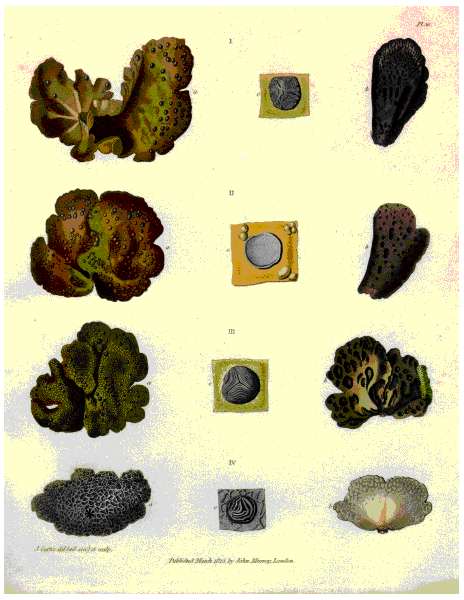

Winter arrived early, game became even scarcer than it had already been, and by 7 September 1821 the expedition's rations were exhausted. Apart from the rare deer they managed to kill, they were reduced to eating barely-nutritious lichens—christened —and the occasional rotting carcass left by packs of wolves. Desperation was such that they even boiled and devoured the leather from their spare boots.

On 13 September the party reached Contwoyto Lake, and the next day arrived at the Contwoyto River. Their disastrous attempts to cross it resulted in the canoes capsizing several times, stranding one of the voyageurs in waist-deep rapids for several minutes. It took four attempts to rescue him. During the incident Franklin had also lost his journals and all of the expedition's meteorological observations.

Their going across the Barren Lands was extremely arduous; the ground was a treacherous expanse of sharp rocks that cut their boots and feet, and was a constant threat to more serious injury. Richardson remarked "if anyone had broken a limb here his fate would have been melancholy indeed, as we could neither have remained with him, nor carried him on with us". The canoes proved difficult to carry and were dropped by the voyageurs—Franklin suspected deliberately—and became completely unusable.

Winter arrived early, game became even scarcer than it had already been, and by 7 September 1821 the expedition's rations were exhausted. Apart from the rare deer they managed to kill, they were reduced to eating barely-nutritious lichens—christened —and the occasional rotting carcass left by packs of wolves. Desperation was such that they even boiled and devoured the leather from their spare boots.

On 13 September the party reached Contwoyto Lake, and the next day arrived at the Contwoyto River. Their disastrous attempts to cross it resulted in the canoes capsizing several times, stranding one of the voyageurs in waist-deep rapids for several minutes. It took four attempts to rescue him. During the incident Franklin had also lost his journals and all of the expedition's meteorological observations.

The voyageurs, who were carrying an average of each and had been promised a ration of of meat a day when they signed up, suffered most from the hunger. Their discontent again turned into rebellion. They secretly discarded some of the heavy equipment, including the

The voyageurs, who were carrying an average of each and had been promised a ration of of meat a day when they signed up, suffered most from the hunger. Their discontent again turned into rebellion. They secretly discarded some of the heavy equipment, including the  Fort Enterprise now lay less than a week's march away, but for some of the starving men, that proved to be an insurmountable barrier. At the back of the line, the two weakest voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, collapsed and were left where they fell. Richardson and Hood were also too weak to continue.

At this point, Franklin split his party. Back, the fittest remaining officer, was sent ahead with three voyageurs to bring food back from Fort Enterprise. Franklin would follow at a slower pace with the remaining voyageurs. Hood and Richardson would stay in their camp, with Hepburn to look after them, in the hope that one of the other parties could bring them food. Franklin was disturbed by the apparent abandonment of Hood and Richardson, but they were insistent that the party would have a better chance of survival without them.

Franklin had only gone a short distance towards Fort Enterprise when four voyageurs—Michel Terohaute, Jean Baptiste Belanger, Perrault, and Fontano—said they were unable to continue and asked to return to Hood and Richardson's camp – Franklin agreed. He staggered on towards Fort Enterprise with his five remaining companions, growing weaker and weaker. No game was to be found, even if any of them had been strong enough to hold a rifle, and recounting the story, Franklin made a comment which would become famous: "There was no , so we drank tea and ate some of our shoes for supper."

Franklin's party reached Fort Enterprise on 12 October, two days after Back. They found it deserted and unstocked. The promised supplies of dried meat had not appeared, and there was nothing to eat except bones from the previous winter, a few rotting skins which had been used as bedding, and a little . A note from Back explained that he had found the fort in this state, and that he was heading towards Fort Providence to look for Akaitcho and his First Nations members. The party despaired.

A voyageur, Joseph Benoit, and an Inuk interpreter,

Fort Enterprise now lay less than a week's march away, but for some of the starving men, that proved to be an insurmountable barrier. At the back of the line, the two weakest voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, collapsed and were left where they fell. Richardson and Hood were also too weak to continue.

At this point, Franklin split his party. Back, the fittest remaining officer, was sent ahead with three voyageurs to bring food back from Fort Enterprise. Franklin would follow at a slower pace with the remaining voyageurs. Hood and Richardson would stay in their camp, with Hepburn to look after them, in the hope that one of the other parties could bring them food. Franklin was disturbed by the apparent abandonment of Hood and Richardson, but they were insistent that the party would have a better chance of survival without them.

Franklin had only gone a short distance towards Fort Enterprise when four voyageurs—Michel Terohaute, Jean Baptiste Belanger, Perrault, and Fontano—said they were unable to continue and asked to return to Hood and Richardson's camp – Franklin agreed. He staggered on towards Fort Enterprise with his five remaining companions, growing weaker and weaker. No game was to be found, even if any of them had been strong enough to hold a rifle, and recounting the story, Franklin made a comment which would become famous: "There was no , so we drank tea and ate some of our shoes for supper."

Franklin's party reached Fort Enterprise on 12 October, two days after Back. They found it deserted and unstocked. The promised supplies of dried meat had not appeared, and there was nothing to eat except bones from the previous winter, a few rotting skins which had been used as bedding, and a little . A note from Back explained that he had found the fort in this state, and that he was heading towards Fort Providence to look for Akaitcho and his First Nations members. The party despaired.

A voyageur, Joseph Benoit, and an Inuk interpreter,

On Franklin's return to England in October 1822, none of the rumours or criticism mattered. The failure to meet the expedition's key goals was overlooked in favour of admiration of his tale of courage in the face of adversity. Franklin, who had been made a commander in his absence, was promoted to captain on 20 November and elected a

On Franklin's return to England in October 1822, none of the rumours or criticism mattered. The failure to meet the expedition's key goals was overlooked in favour of admiration of his tale of courage in the face of adversity. Franklin, who had been made a commander in his absence, was promoted to captain on 20 November and elected a

The Coppermine expedition of 1819–1822 was a British overland undertaking to survey and chart the area from

The Coppermine expedition of 1819–1822 was a British overland undertaking to survey and chart the area from Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

to the north coast of North America, eastwards from the mouth of the Coppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave Region, North Slave and Kitikmeot Region, Nunavut, Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake, a ...

. The expedition was organised by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

as part of its attempt to discover and map the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

. It was the first of three Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

expeditions to be led by John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Northern Canada, Canadia ...

and also included George Back

Admiral Sir George Back (6 November 1796 – 23 June 1878) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic, naturalist and artist. He was born in Stockport.

Career

As a boy, he went to sea as a volunteer in the frigate ...

and John Richardson, both of whom later became notable Arctic explorers in their own right.

The expedition was plagued by poor planning, bad luck and unreliable allies. The local fur trading

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

companies and native peoples offered less assistance than expected, and the dysfunctional supply line, coupled with unusually harsh weather and the resulting absence of game, meant the explorers were never far from starvation. Eventually, the party reached the Arctic coast, but only explored roughly before turning back due to the onset of winter and the exhaustion of their supplies.

The party desperately retreated across uncharted territory in a state of starvation, often with nothing more than lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

to eat; 11 of the 22 members died amid accusations of murder and cannibalism. The survivors were rescued by members of the Yellowknives Nation, who had previously given them up for dead.

In the aftermath, local fur traders criticised Franklin for his haphazard planning and failure to adapt. Back in Britain he was received as a hero and fêted for the courage he had shown in extreme adversity. The expedition captured the public imagination, and in reference to a desperate measure he took while starving, he became known as "the man who ate his boots".

Background

In the years following the

In the years following the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the British Navy, under the influence of Sir John Barrow

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1764 – 23 November 1848) was an English geographer, linguist, writer and civil servant best known for serving as the Second Secretary to the Admiralty from 1804 until 1845.

Early life

Barrow was b ...

, turned its attention to the discovery of the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

, a putative sea route around the north coast of North America which would allow European ships easy access to the markets of the Orient

The Orient is a term referring to the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of the term ''Occident'', which refers to the Western world.

In English, it is largely a meto ...

. Evidence for the existence of a passage came from the fact that whalers in the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

had killed whales which carried tusk

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine tooth, canine teeth, as with Narwhal, narwhals, chevrotains, musk deer, water deer, muntjac, pigs, ...

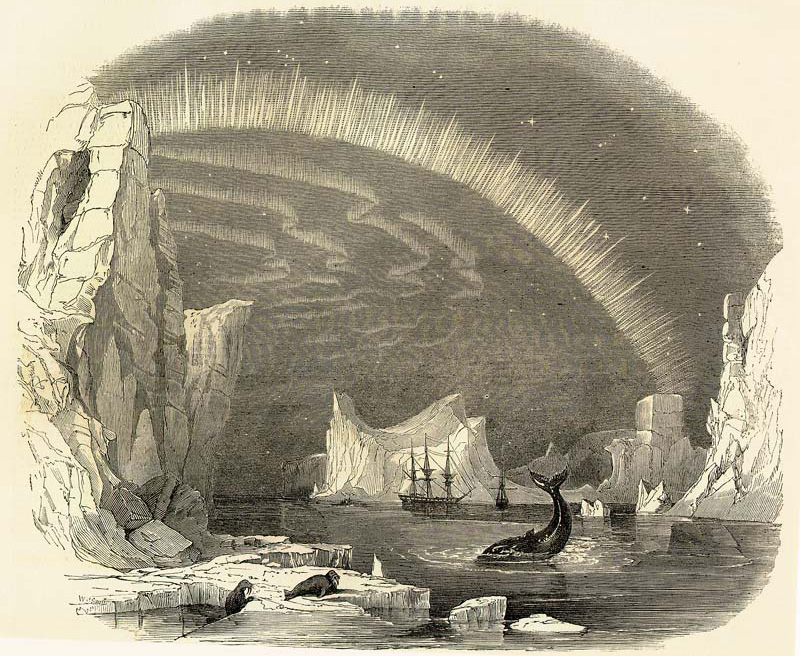

s of the type used in Greenland and , but the maze of islands north of the continent was almost completely unmapped; and it was not known whether a navigable, ice-free passage existed.

By 1819 the northern coast had been glimpsed only twice by Europeans. In 1771 Samuel Hearne

Samuel Hearne (February 1745 – November 1792) was an English explorer, fur-trader, author and naturalist.

He was the first European to make an overland excursion across northern Canada to the Arctic Ocean, specifically to Coronation Gulf, vi ...

had followed the Coppermine River to the sea at a point around east of the Bering Strait. He was followed in 1789 by Alexander Mackenzie, who traced what is now the Mackenzie River

The Mackenzie River (French: ; Slavey language, Slavey: ' èh tʃʰò literally ''big river''; Inuvialuktun: ' uːkpɑk literally ''great river'') is a river in the Canadian Canadian boreal forest, boreal forest and tundra. It forms, ...

to open sea west of the mouth of the Coppermine.

In 1818, Barrow had sent his first expedition to seek the Northwest Passage. Led by John Ross, it ended ignominiously when Ross entered the Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound () is a body of water in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern entrance to the Parry Channel and the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin ...

, the true entrance to the Northwest Passage, but judging it to be a bay turned around and returned to Britain. At the same time, David Buchan

David Buchan (c. 1780 – after 8 December 1838) was a Scottish naval officer and Arctic explorer.

Family

In 1802 or 1803, he married Maria Adye. They had at least three children.

Exploration

In 1806, Buchan was appointed as a lieutenant ...

made an attempt to sail directly to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

from Britain (Barrow was a believer in the Open Polar Sea

The Open Polar Sea was a conjectured ice-free body of water that was believed to encircle the North Pole. Although this theory was widely accepted and served as a basis for many exploratory expeditions aimed at reaching the North Pole by sea or ...

hypothesis), but returned only with the news that the pack ice north of Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

was a barrier which could not be breached.

The following year, Barrow planned two further expeditions to the Arctic. A seaborne expedition under William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Passa ...

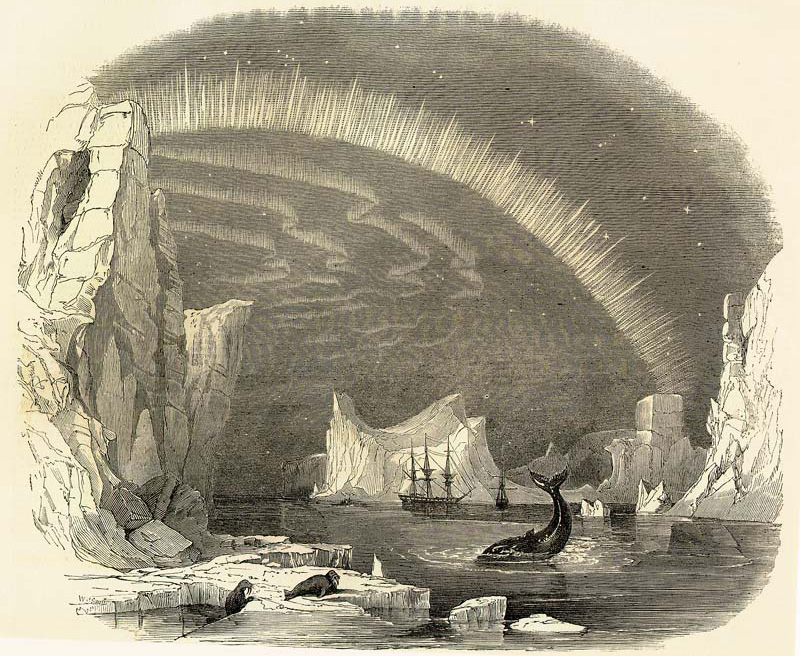

would follow on from Ross' work, seeking an entrance to the Northwest Passage from Lancaster Sound. Simultaneously, a party would travel overland to the north coast by way of the Coppermine River and map as much of the coastline as possible, and perhaps even rendezvous with Parry's ships. John Franklin, a lieutenant who had commanded one of David Buchan's ships the previous year, was chosen to lead the overland party.

Preparations

Franklin's orders were somewhat general in nature. He was to travel overland toGreat Slave Lake

Great Slave Lake is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories, Canada (after Great Bear Lake), List of lakes by depth, the deepest lake in North America at , and the List of lakes by area, tenth-largest lake in the world by area. It ...

, and from there go to the coast by way of the Coppermine River. On reaching the coast he was advised to head east towards Repulse Bay

Repulse Bay or Tsin Shui Wan is a bay in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, located in the Southern District, Hong Kong, Southern District, Hong Kong. It is one of the most expensive residential areas in the world.

Geography

Repulse B ...

and William Edward Parry's (hopefully victorious) ships, but if it seemed better he was also given the option of going west to map the coastline between the Coppermine and the Mackenzie Rivers, or even heading north into wholly unknown seas.

More serious than the ambiguity of the instructions was the fact that the expedition was organised with an extremely limited budget. John Franklin was to take only a minimum of naval personnel, and would be reliant on outside help for much of the journey. Manual assistance was meant to be provided by Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

voyageurs

Voyageurs (; ) were 18th- and 19th-century French and later French Canadians and others who transported furs by canoe at the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ...

supplied by the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

and their rivals the North West Company

The North West Company was a Fur trade in Canada, Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada a ...

, while the local Yellowknives would act as guides and provide food should John Franklin's supplies run out.

Only four naval personnel accompanied John Franklin; the doctor, naturalist and second in command John Richardson; two midshipmen named Robert Hood

Robert Hood (born 1965) is an American electronic music producer and DJ. He is a founding member of the group Underground Resistance as a 'Minister of Information' with Mad Mike Banks and Jeff Mills. He is often considered to be one of the fo ...

and George Back

Admiral Sir George Back (6 November 1796 – 23 June 1878) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic, naturalist and artist. He was born in Stockport.

Career

As a boy, he went to sea as a volunteer in the frigate ...

, the latter of whom had sailed with David Buchan

David Buchan (c. 1780 – after 8 December 1838) was a Scottish naval officer and Arctic explorer.

Family

In 1802 or 1803, he married Maria Adye. They had at least three children.

Exploration

In 1806, Buchan was appointed as a lieutenant ...

in 1818; and an ordinary seaman named John Hepburn. As documented in his journals, a second ordinary seaman, Samuel Wilkes, was initially assigned to the party, but fell ill on arriving in Canada and played no further part in the expedition, returning to England with dispatches. He later served as armourer on in Captain Parry's 1821 expedition.

Expedition

Cumberland House

The Coppermine Expedition sailed fromGravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

on 23 May 1819 on a Hudson's Bay Company supply ship, after three months of planning, and immediately hit a note of farce. The ship had stopped briefly off the Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

coast, where George Back had business to attend to, but before he had returned a favourable wind blew up and the ship sailed off, leaving Back to make his own way to their next stop in Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

by stagecoach and ferry.

A more serious problem arose in Stromness

Stromness (, ; ) is the second-most populous town in Orkney, Scotland. It is in the southwestern part of Mainland, Orkney. It is a burgh with a parish around the outside with the town of Stromness as its capital.

Etymology

The name "Stromnes ...

when the expedition, now reunited with Back, attempted to hire local boatmen to act as manhaulers for the first part of the overland trek. The sudden success of the herring fisheries that year meant that the Orkneymen were far less keen to sign up than had been anticipated. Only four men were recruited, and even they agreed to go only as far as Fort Chipewyan

Fort Chipewyan , commonly referred to as Fort Chip, is an unincorporated hamlet in northern Alberta, Canada, within the Regional Municipality (RM) of Wood Buffalo.

History

Fort Chipewyan is one of the oldest European settlements in the Provi ...

on Lake Athabasca

Lake Athabasca ( ; French: ''lac Athabasca''; from Woods Cree: , " herethere are plants one after another") is in the north-west corner of Saskatchewan and the north-east corner of Alberta between 58° and 60° N in Canada. The lake is ...

.

On 30 August 1819, Franklin's men reached York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill.

York ...

, the main port on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

, to begin the trek to Great Slave Lake. They immediately encountered the first of the supply problems which were to plague the expedition. Much of the assistance offered by the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company failed to materialise; the companies had spent the preceding years in a state of virtual war and cooperation between them was virtually nonexistent – they had few resources to spare.

Franklin was provided with a boat too small to carry all his supplies and proceeded—he was assured the rest would be sent on—along normal trading routes to Cumberland House

Cumberland House was a mansion on the south side of Pall Mall in London, England. It was built in the 1760s by Matthew Brettingham for Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany and was originally called York House. The Duke of York died in 1767 a ...

; little more than a log cabin which was home to 30 Hudson's Bay men. He and his men spent the winter here. The winter of 1819 was a harsh one and ominously, the local First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

who came to the post for supplies reported that game had become so scarce that some families were resorting to cannibalism to survive.

Fort Chipewyan

The following January, Franklin, Back and Hepburn formed an advance party to head through the pine forests to Fort Chipewyan, to hire voyageurs and arrange supplies for the next leg of the expedition. Led by Canadian guides, the Britons, who had no experience of the harsh winters of the region, found the journey extremely arduous. The constant and extreme cold froze their tea almost immediately after it had been poured, as well as the mercury in their thermometers. Without tents, they were grateful for snowfall, as it provided an extra layer of insulation over their blankets. Franklin later wrote that the journey brought "a great inter-mixture of agreeable and disagreeable circumstances. Could the amount of each be balanced, I suspect the latter would much preponderate."

The advance party arrived at Fort Chipewyan in late March, having covered in six weeks. Once there, Franklin found equipping his expedition far more difficult than had been anticipated. The harsh winter meant that food was barely available, and he had to make do with a vague promise that hunters would feed them en route, and that the chief of the Coppermine First Nations would offer assistance.

The best voyageurs were preoccupied with the conflict between the two fur trading companies, or unwilling to risk a journey into unknown terrain, far outside their normal range and with uncertain supplies. Eventually, Franklin was able to recruit a team of 16 voyageurs, but most of the men fell well below the standard he desired.

Without tents, they were grateful for snowfall, as it provided an extra layer of insulation over their blankets. Franklin later wrote that the journey brought "a great inter-mixture of agreeable and disagreeable circumstances. Could the amount of each be balanced, I suspect the latter would much preponderate."

The advance party arrived at Fort Chipewyan in late March, having covered in six weeks. Once there, Franklin found equipping his expedition far more difficult than had been anticipated. The harsh winter meant that food was barely available, and he had to make do with a vague promise that hunters would feed them en route, and that the chief of the Coppermine First Nations would offer assistance.

The best voyageurs were preoccupied with the conflict between the two fur trading companies, or unwilling to risk a journey into unknown terrain, far outside their normal range and with uncertain supplies. Eventually, Franklin was able to recruit a team of 16 voyageurs, but most of the men fell well below the standard he desired.

Fort Enterprise

Reunited with Hood and Richardson, the party left for Great Slave Lake in July, reaching the trading post at

Reunited with Hood and Richardson, the party left for Great Slave Lake in July, reaching the trading post at Fort Providence

Fort Providence () is a hamlet in the South Slave Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Located west of Great Slave Lake, it has all-weather road connections by way of the Yellowknife Highway (Great Slave Highway) branch off the Macke ...

on its northern shore ten days later. Here they met Akaitcho

Akaitcho (variants: Akaicho or Ekeicho; translation: "Big-Foot" or "Big-Feet"; meaning: "like a wolf with big paws, he can travel long distances over snow") (ca. 1786–1838) was a Copper Indian, and Chief of the Yellowknives. His territory incl ...

, the leader of the local Yellowknives (or Copper Dene) First Nation who had been recruited by the North West Company as guides and hunters for Franklin's men. Akaitcho, described as a man "of great penetration and shrewdness" understood the concept of the Northwest Passage, and patiently listened as Franklin explained that its use would bring wealth to his people. Apparently realising that Franklin was exaggerating the benefits, he asked a question which Franklin was unable to answer: why, if the Northwest Passage was so crucial to trade, had it not been discovered already?

His point effectively made, Akaitcho discussed his terms with Franklin. In return for the cancellation of his tribe's debts to the North West Company, and a supply of weapons, ammunition and tobacco, his men would hunt and guide for Franklin on the northward journey down the Coppermine River, and leave depots of food for their return. However, they would not enter the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

lands at the far north of the river, since the Yellowknives and the Inuit viewed each other with mutual hostility and suspicion. Akaitcho warned Franklin that in such a hard year, he could not guarantee food would always be available. Akaitcho and his band have been described (By Franklin, Richardson, Back, HoodHouston, C.S., ed. To the Arctic by Canoe 1819-1821: The Journal and Paintings of Robert Hood, Midshipman with Franklin 1974, McGill-Queen's University Press: Montreal. and others) as hired guides and hunters.

Franklin and his men spent the remainder of the summer of 1820 trekking north to a point on the bank of the Snare River which Akaitcho had chosen as their winter quarters. Food quickly ran short and the voyageurs began to lose faith in their leader; Franklin's threats of severe punishment prevented a mutiny in the short term, but eroded the remaining goodwill felt by the men. The encampment, which Franklin named Fort Enterprise, was reached without further incident, and wooden huts were constructed as winter quarters.

Coppermine River

The expedition's second winter was another difficult one. Supplies arrived only intermittently; the rival companies each preferring to let the other provide them. Ammunition ran short, and the First Nations hunters were less effective than had been hoped. Finally, with the party at risk of starvation, Back was sent back to Fort Providence to browbeat the companies into action. After a journey on snowshoes, often with no shelter beyond blankets and a deerskin in temperatures as low as , Back returned having secured enough supplies to meet the expedition's immediate needs.

The expedition's second winter was another difficult one. Supplies arrived only intermittently; the rival companies each preferring to let the other provide them. Ammunition ran short, and the First Nations hunters were less effective than had been hoped. Finally, with the party at risk of starvation, Back was sent back to Fort Providence to browbeat the companies into action. After a journey on snowshoes, often with no shelter beyond blankets and a deerskin in temperatures as low as , Back returned having secured enough supplies to meet the expedition's immediate needs.

There was also continuing unrest in the camp. The voyageurs, led by the two interpreters Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, rebelled. Franklin's threats were ineffective; St. Germain and Adam insisting that as continuing into the wilderness would mean certain death, the threat of execution for mutiny was laughable. Negotiation by Willard Wentzel, the North West Company's representative, eventually restored an uneasy truce. The discord was not confined to the voyageurs; Back and Hood had fallen out over their rivalry for the affections of a Yellowknives girl nicknamed Greenstockings, and would have fought a duel with pistols over her had John Hepburn not removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation was defused when Back was dispatched south. Hood subsequently fathered a child with Greenstockings.

The winter of 1820–21 passed, and Franklin set out again on 4 June 1821. His plans for the coming summer were vague; he had decided to explore east from the mouth of the Coppermine in the hope of either meeting William Edward Parry or reaching Repulse Bay, where he might obtain adequate supplies from local Inuit to allow him to return directly to York Factory by way of Hudson Bay. However, if Parry failed to appear, or he was unable to reach Repulse Bay he would either retrace his outward route or, if it seemed better, return directly to Fort Enterprise across the uncharted Barren Lands to the east of the Coppermine River.

There was also continuing unrest in the camp. The voyageurs, led by the two interpreters Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, rebelled. Franklin's threats were ineffective; St. Germain and Adam insisting that as continuing into the wilderness would mean certain death, the threat of execution for mutiny was laughable. Negotiation by Willard Wentzel, the North West Company's representative, eventually restored an uneasy truce. The discord was not confined to the voyageurs; Back and Hood had fallen out over their rivalry for the affections of a Yellowknives girl nicknamed Greenstockings, and would have fought a duel with pistols over her had John Hepburn not removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation was defused when Back was dispatched south. Hood subsequently fathered a child with Greenstockings.

The winter of 1820–21 passed, and Franklin set out again on 4 June 1821. His plans for the coming summer were vague; he had decided to explore east from the mouth of the Coppermine in the hope of either meeting William Edward Parry or reaching Repulse Bay, where he might obtain adequate supplies from local Inuit to allow him to return directly to York Factory by way of Hudson Bay. However, if Parry failed to appear, or he was unable to reach Repulse Bay he would either retrace his outward route or, if it seemed better, return directly to Fort Enterprise across the uncharted Barren Lands to the east of the Coppermine River.

The journey down the Coppermine River took far longer than planned, and Franklin quickly lost faith in his First Nations guides, who in fact knew the area little better than he did, and assured him that the sea was close, then far, then close again. The ice on the rivers and lakes was still firm, and for the first of the journey the canoes had to be dragged on

The journey down the Coppermine River took far longer than planned, and Franklin quickly lost faith in his First Nations guides, who in fact knew the area little better than he did, and assured him that the sea was close, then far, then close again. The ice on the rivers and lakes was still firm, and for the first of the journey the canoes had to be dragged on sledges

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners ...

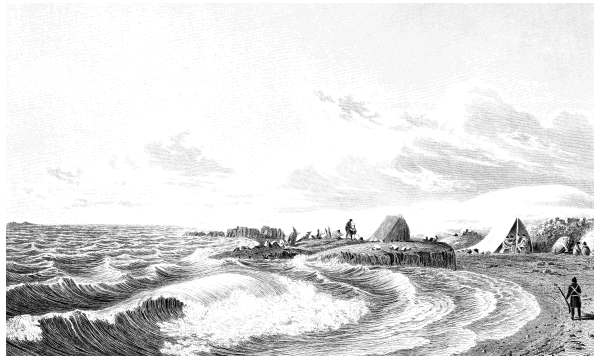

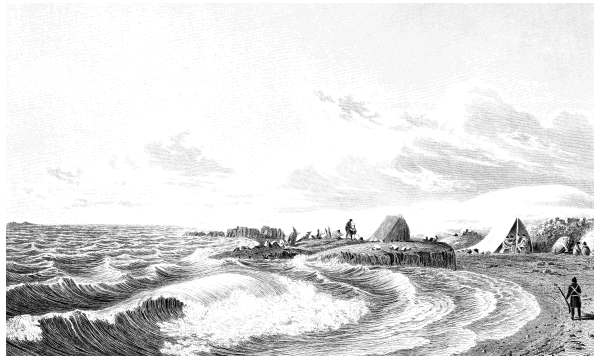

. The Arctic Ocean was finally sighted on 14 July, shortly before the expedition encountered its first Inuit camp. The Inuit fled, and Franklin's men never had the opportunity to make further contact or trade for supplies as he had hoped. The abandoned camp gave a further indication of the scarcity of food in the area; the stocks of dried salmon were rotting and maggot-infested, and the drying meat consisted mainly of small birds and mice.

The First Nations guides turned for home as had been agreed, as did Wentzel, leaving Franklin with fifteen voyageurs and his four Britons. Franklin gave orders to those departing that caches of food were to be left on route and that most importantly Fort Enterprise be stocked with a large amount of dried meat. With the lateness of the season the latter point was crucial because Franklin now feared that if, as seemed likely, he failed to reach Repulse Bay, the sea would freeze and prevent him returning to the mouth of the Coppermine River. If so, he would be forced to make a direct return across the Barren Lands, where he and his men would be dependent on whatever food they could forage. There was therefore a real risk that they would be close to starvation by the time they reached Fort Enterprise. Franklin frequently reiterated that well-stocked huts were crucial to their survival.

At the mouth of the Coppermine, Wentzel, with four voyageurs and at least three Copper Dene, returned south, as planned. Akaitcho's band, having fulfilled their obligations to conduct the expedition to the "Frozen Ocean", dispersed for their summer hunting and fishing. Franklin set off east in three canoes with enough food for fourteen days. Their progress was impeded by storms which frequently damaged the canoes. Attempts to supplement their rations by hunting were so unsuccessful that Franklin suspected the voyageurs of deliberately failing to find game, in order to compel him to turn around.

On 22 August, after about of coastline had been mapped, Franklin stopped at a spot he designated as Point Turnagain, on the Kent Peninsula

Kiillinnguyaq, formerly the Kent Peninsula, is a large Arctic peninsula, almost totally surrounded by water, in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut. Were it not for a isthmus at the southeast corner it would be a long island parallel to the coast. ...

, about northeast of Cape Flinders

Cape Flinders is a headland in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut. It is located on the western point of the Kent Peninsula, now known as Kiillinnguyaq.

The cape was named by Sir John Franklin in 1821 after the navigator Matthew Flinde ...

. As he had feared, rough seas and the damage to their canoes made a return via the Coppermine impracticable. The party decided on a return via the Hood River, from which they would attempt to make an overland return across the Barren Lands.

Return journey and starvation

Their going across the Barren Lands was extremely arduous; the ground was a treacherous expanse of sharp rocks that cut their boots and feet, and was a constant threat to more serious injury. Richardson remarked "if anyone had broken a limb here his fate would have been melancholy indeed, as we could neither have remained with him, nor carried him on with us". The canoes proved difficult to carry and were dropped by the voyageurs—Franklin suspected deliberately—and became completely unusable.

Winter arrived early, game became even scarcer than it had already been, and by 7 September 1821 the expedition's rations were exhausted. Apart from the rare deer they managed to kill, they were reduced to eating barely-nutritious lichens—christened —and the occasional rotting carcass left by packs of wolves. Desperation was such that they even boiled and devoured the leather from their spare boots.

On 13 September the party reached Contwoyto Lake, and the next day arrived at the Contwoyto River. Their disastrous attempts to cross it resulted in the canoes capsizing several times, stranding one of the voyageurs in waist-deep rapids for several minutes. It took four attempts to rescue him. During the incident Franklin had also lost his journals and all of the expedition's meteorological observations.

Their going across the Barren Lands was extremely arduous; the ground was a treacherous expanse of sharp rocks that cut their boots and feet, and was a constant threat to more serious injury. Richardson remarked "if anyone had broken a limb here his fate would have been melancholy indeed, as we could neither have remained with him, nor carried him on with us". The canoes proved difficult to carry and were dropped by the voyageurs—Franklin suspected deliberately—and became completely unusable.

Winter arrived early, game became even scarcer than it had already been, and by 7 September 1821 the expedition's rations were exhausted. Apart from the rare deer they managed to kill, they were reduced to eating barely-nutritious lichens—christened —and the occasional rotting carcass left by packs of wolves. Desperation was such that they even boiled and devoured the leather from their spare boots.

On 13 September the party reached Contwoyto Lake, and the next day arrived at the Contwoyto River. Their disastrous attempts to cross it resulted in the canoes capsizing several times, stranding one of the voyageurs in waist-deep rapids for several minutes. It took four attempts to rescue him. During the incident Franklin had also lost his journals and all of the expedition's meteorological observations.

The voyageurs, who were carrying an average of each and had been promised a ration of of meat a day when they signed up, suffered most from the hunger. Their discontent again turned into rebellion. They secretly discarded some of the heavy equipment, including the

The voyageurs, who were carrying an average of each and had been promised a ration of of meat a day when they signed up, suffered most from the hunger. Their discontent again turned into rebellion. They secretly discarded some of the heavy equipment, including the fishing net

A fishing net or fish net is a net (device), net used for fishing. Fishing nets work by serving as an improvised fish trap, and some are indeed rigged as traps (e.g. #Fyke nets, fyke nets). They are usually wide open when deployed (e.g. by cast ...

s, which would prove a serious loss. Richardson wrote that they "became desperate and were perfectly regardless of the commands of the officers."

The only thing that prevented their desertion was the fact that they did not know how to find Fort Enterprise by themselves. However, they began to realise that Franklin had little idea of its location as well. His compass was of little use as the magnetic deviation

Magnetic deviation is the error induced in a compass by ''local'' magnetic fields, which must be allowed for, along with magnetic declination, if accurate bearings are to be calculated. (More loosely, "magnetic deviation" is used by some to mean ...

for the area was unknown and the constant cloud cover made celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space or on the surface ...

impossible. A full-scale mutiny was averted only by their reaching a large river on 26 September, undoubtedly the Coppermine.

The party's jubilation at having reached the river quickly turned to despair when it became obvious it would be impossible to cross the river to reach Fort Enterprise—without boats. Franklin estimated it lay away on the far bank. The fast-flowing river was wide in places, and attempts to find a spot where it could be forded proved futile. The voyageurs, according to Richardson, "bitterly execrated their folly in breaking the canoe" and became "careless and disobedient... ndceased to dread punishment or hope for reward." One of them, Juninus, slipped away, perhaps hoping to reach safety by himself, and never returned. Richardson himself risked his life trying to swim across the river with a line tied around his waist, but losing the feeling in his limbs he sank to the riverbed and had to be hauled back. Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

sapped his strength, leaving him a virtual invalid.

With the starving party weakening rapidly, the situation was saved by Pierre St Germain, who alone had the strength and willpower to construct a makeshift one-man canoe from willow branches and canvas. The other men cheered when, on 4 October, he crossed the river, trailing a lifeline. The rest of the party crossed one at a time. The boat sank lower and lower in the water as they did so, but all crossed safely.

Fort Enterprise now lay less than a week's march away, but for some of the starving men, that proved to be an insurmountable barrier. At the back of the line, the two weakest voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, collapsed and were left where they fell. Richardson and Hood were also too weak to continue.

At this point, Franklin split his party. Back, the fittest remaining officer, was sent ahead with three voyageurs to bring food back from Fort Enterprise. Franklin would follow at a slower pace with the remaining voyageurs. Hood and Richardson would stay in their camp, with Hepburn to look after them, in the hope that one of the other parties could bring them food. Franklin was disturbed by the apparent abandonment of Hood and Richardson, but they were insistent that the party would have a better chance of survival without them.

Franklin had only gone a short distance towards Fort Enterprise when four voyageurs—Michel Terohaute, Jean Baptiste Belanger, Perrault, and Fontano—said they were unable to continue and asked to return to Hood and Richardson's camp – Franklin agreed. He staggered on towards Fort Enterprise with his five remaining companions, growing weaker and weaker. No game was to be found, even if any of them had been strong enough to hold a rifle, and recounting the story, Franklin made a comment which would become famous: "There was no , so we drank tea and ate some of our shoes for supper."

Franklin's party reached Fort Enterprise on 12 October, two days after Back. They found it deserted and unstocked. The promised supplies of dried meat had not appeared, and there was nothing to eat except bones from the previous winter, a few rotting skins which had been used as bedding, and a little . A note from Back explained that he had found the fort in this state, and that he was heading towards Fort Providence to look for Akaitcho and his First Nations members. The party despaired.

A voyageur, Joseph Benoit, and an Inuk interpreter,

Fort Enterprise now lay less than a week's march away, but for some of the starving men, that proved to be an insurmountable barrier. At the back of the line, the two weakest voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, collapsed and were left where they fell. Richardson and Hood were also too weak to continue.

At this point, Franklin split his party. Back, the fittest remaining officer, was sent ahead with three voyageurs to bring food back from Fort Enterprise. Franklin would follow at a slower pace with the remaining voyageurs. Hood and Richardson would stay in their camp, with Hepburn to look after them, in the hope that one of the other parties could bring them food. Franklin was disturbed by the apparent abandonment of Hood and Richardson, but they were insistent that the party would have a better chance of survival without them.

Franklin had only gone a short distance towards Fort Enterprise when four voyageurs—Michel Terohaute, Jean Baptiste Belanger, Perrault, and Fontano—said they were unable to continue and asked to return to Hood and Richardson's camp – Franklin agreed. He staggered on towards Fort Enterprise with his five remaining companions, growing weaker and weaker. No game was to be found, even if any of them had been strong enough to hold a rifle, and recounting the story, Franklin made a comment which would become famous: "There was no , so we drank tea and ate some of our shoes for supper."

Franklin's party reached Fort Enterprise on 12 October, two days after Back. They found it deserted and unstocked. The promised supplies of dried meat had not appeared, and there was nothing to eat except bones from the previous winter, a few rotting skins which had been used as bedding, and a little . A note from Back explained that he had found the fort in this state, and that he was heading towards Fort Providence to look for Akaitcho and his First Nations members. The party despaired.

A voyageur, Joseph Benoit, and an Inuk interpreter, Tatannuaq

Tatannuaq (, ; – early 1834), also known as Tattannoeuck or Augustus, was an Inuit, Inuk interpreter for two of John Franklin's Arctic expeditions. Originally from a group of Inuit living north of Churchill, Manitoba, Churchill, Rupert's L ...

("Augustus") set off downriverFranklin, J. and J. Richardson, Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. 1828, Philadelphia: Carey, Lea, and Carey. in the hope of meeting a Copper Dene band under Chief Akaitcho, who had been helping the expedition throughout. The rest of the group remained, too weak to go any further. Two of the voyageurs, François Semandrè and Joseph Peltier, lay down crying and waited to die, and even the normally optimistic Franklin wrote of how quickly his strength was evaporating. None of them had eaten meat for four weeks.

Murder

Of the four voyageurs who had left Franklin's party to return to Hood and Richardson, only Terohaute reached the camp, having taken several days to cover the from where they left Franklin. He told the Britons that he had become separated from the others, and assumed they would be following. Whatever doubts the officers may have had about his story gave way to gratitude when he presented them with meat, which he said had come from a hare and partridge he had managed to kill on the way. Two days later he went hunting and brought back meat he said came from a wolf he had found. The Britons were delighted, and eagerly devoured the meat. Over the next few days, however, Terohaute's behaviour became more and more erratic. He disappeared for short periods, refusing to say where he had gone. He would not gather , and would sneak and eat meat at night after believing his companions were asleep. When asked to go hunting he refused, replying that "there are no animals, you had better kill and eat me." He later accused the Britons of having eaten his uncle. At some point—Richardson's journal is unclear on when—Richardson and Hood began to suspect that Terohaute had killed the three missing voyageurs, and was disappearing from camp to feed on their corpses. The "wolf meat" they had eaten was probably human flesh. On 20 October, while Richardson and Hepburn were foraging, they heard a shot from the camp. They found Hood dead, and Terohaute standing with a gun in his hand. Terohaute's explanation was that Hood had been cleaning his gun and that it had gone off, shooting him through the head. The claim was self-evidently absurd; the rifle was too long for a man to shoot himself with, moreover Hood had been shot in the back of the head, apparently while reading a book on Christian scripture. But with Terohaute stronger than them and armed, there was nothing John Hepburn and Richardson could do for the next three days, as Terohaute refused to let them out of his sight and became more and more aggressive, repeatedly asking to know if they thought he had murdered Hood. Finally, on 23 October, Terohaute left them for a short time on the pretenses of gathering lichen. Richardson took the opportunity to load his pistol, and on Terohaute's return, shot him dead. They discovered that Terohaute had, in fact, not collected any lichen at all but actually had prepared a rifle; seemingly it was to be used on the two not long after rejoining them.Rescue

Richardson and Hepburn struggled on to Fort Enterprise and were appalled by the scene when they arrived on 29 October 1821. Of the four men who remained, only Peltier was strong enough to stand and greet them. The floorboards had been dug up for firewood, and the skins which covered the windows had been removed and eaten by the starving men. Richardson wrote that "the ghastly countenances, dilated eyeballs and sepulchral voices of Captain John Franklin and those with him were more than we could at first bear." For over a week the men at Fort Enterprise subsisted on and rotten deerskins, which they ate complete with the maggots, which tasted "as fine as gooseberries." Two of the voyageurs, Peltier and Samandré, died on the night of 1 November. The interpreter, Jean Baptiste Adam, was close to death. Hepburn's limbs began to swell with protein deficiencyoedema

Edema (American English), also spelled oedema (British English), and also known as fluid retention, swelling, dropsy and hydropsy, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may inclu ...

. Finally, on 7 November, help arrived with the arrival of three of Akaitcho's men, with whom Back—who had also lost a man (Gabriel Beauparlant) to starvation—had finally managed to make contact. They brought food, caught fish for the survivors, and treated them "with the same tenderness they would have bestowed on their own infants." After building up their strength for a week, they left Fort Enterprise on 15 November, arriving at Fort Providence on 11 December.

Akaitcho explained why Fort Enterprise had not been stocked with food as promised. Part of the reason was that three of his hunters had been killed when they fell through the ice on Little Marten Lake, and he had not been supplied with ammunition at Fort Providence, but he admitted the main reason the fort had been abandoned; he had believed that the white men's expedition was the height of folly, and that they would not return to Fort Enterprise alive. In spite of this, Franklin refused to blame Akaitcho, who had shown him much kindness during the rescue and because of the ongoing dispute between the fur companies, had not received the payment he had been promised.

Besides the three hunters who drowned in Little Marten Lake, three Copper Dene—a man and his wife and child—were left behind by Wentzel, who assumed that they must have died.

Aftermath

By almost any objective standard, the expedition had been a disaster. Franklin had travelled and lost 11 of his 19 men, only to map a small portion of coastline. He got nowhere near his goal of Repulse Bay or to meeting up with William Edward Parry's ships. When the party arrived back at York Factory in July 1822, George Simpson of the Hudson's Bay Company, who had objected to John Franklin's expedition from the start, wrote that "They do not feel themselves at liberty to enter into the particulars of their disastrous enterprise, and I fear they have not fully achieved the object of their mission." Simpson, and other fur traders who knew the terrain, were scathing in their descriptions of the expedition's poor planning and assessment of Franklin's competence. His reluctance to deviate from his original plan, even when it became obvious that supplies and game would be too scarce to complete the journey safely, were cited as evidence of his inflexibility and inability to adapt to a changing situation. Had Franklin been more experienced, he might have reconsidered his goals, or abandoned the expedition altogether. In a particularly harshly worded letter, Simpson also wrote of Franklin's physical failings; " ehas not the physical powers required for the labor of moderate Voyaging in this country; he must have three meals , Tea is indispensable, and with the utmost exertion he cannot walk above Eight miles in one day, so that it does not follow if those Gentlemen are unsuccessful that the difficulties are insurmountable." However, it should be kept in mind that many of the fur traders resented having had to assist Franklin in the first place, and Simpson in particular was angry with what he saw as Franklin's support for the rival North West Company in their trade war. There were also dark murmurings about what exactly had happened to Hood and Terohaute. The only account of the incident was Richardson's, published after consultation with Franklin, and there was nothing to prove that he and Hepburn had not killed and eaten Hood and the four voyageurs themselves. Wentzel, the North West Company interpreter who was blamed for failing to ensure that Fort Enterprise was stocked, went so far as to accuse Richardson of murder, and demanded that he be brought to trial. Back subsequently wrote to him that "to tell the truth Wentzel, things have taken place which not be known." TheAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

launched no official inquiry and the matter was quietly dropped.

On Franklin's return to England in October 1822, none of the rumours or criticism mattered. The failure to meet the expedition's key goals was overlooked in favour of admiration of his tale of courage in the face of adversity. Franklin, who had been made a commander in his absence, was promoted to captain on 20 November and elected a

On Franklin's return to England in October 1822, none of the rumours or criticism mattered. The failure to meet the expedition's key goals was overlooked in favour of admiration of his tale of courage in the face of adversity. Franklin, who had been made a commander in his absence, was promoted to captain on 20 November and elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

, while Back was made a lieutenant.

Franklin's account of the expedition, published in 1823, was regarded as a classic of travel literature, and when the publishing company could not keep up with demand, second-hand copies sold for up to ten guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

s. Ordinary people would point him out in the street and recalling his desperate measures to avoid starvation, he became affectionately known as "the man who ate his boots".

Franklin made another expedition to the Arctic in 1825. With a party which included Richardson and Back, he journeyed down the Mackenzie River to map a further section of the coast of North America. This time the expedition was better organised, with less reliance on outside help, and all the major objectives were met. After stints commanding ships outside the Arctic, and an unhappy period as Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

, he led a final expedition to discover the Northwest Passage in 1845. Franklin vanished almost without trace, with all 128 of his men, and the mystery of his fate has still to be fully discovered.

The story of the Coppermine Expedition served as an influence on Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

, who eventually became the first man to navigate the entire Northwest Passage, as well as the first to reach the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

. At the age of fifteen he read Franklin's account and decided that he wanted to be a polar explorer

This list is for recognised pioneering explorers of the polar regions. It does not include subsequent travelers and expeditions.

Polar explorers

* Jameson Adams

* Mark Agnew

* Stian Aker

* Valerian Albanov

* Roald Amundsen

* Salomon August ...

. He recalled:

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * Limited access * * * * {{Authority control 19th century in Canada 19th century in the Arctic 19th-century history of the Royal Navy 1819 in Canada 1819 in the British Empire 1820 in Canada 1821 in Canada 1822 in Canada Arctic expeditions Expeditions from the United Kingdom History of Nunavut History of the Northwest Territories Maritime history of Canada