Constantine II of Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Constantine II (, ; 2 June 1940 – 10 January 2023) was the last

In 1944, at the end of World War II, Nazi Germany gradually withdrew from Greece. While the majority of exiled Greeks were able to return to their country, the royal family had to remain in exile because of the growing republican opposition at home. Britain tried to reinstate George II, who remained in exile in London, but most of the resistance, in particular the communists, were opposed. Instead, George had to appoint from exile a Regency Council headed by Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens, who immediately appointed a republican-majority government headed by Nikolaos Plastiras. George, who was humiliated, ill and powerless, considered abdicating for a time in favour of his brother, but eventually decided against it.

Prince Paul, who was more combative but also more popular than his brother, would have liked to return to Greece as heir to the throne as early as the liberation of Athens in 1944, as he believed that back in his country he would have been quickly proclaimed regent, which would have blocked the way for Damaskinos and made it easier to restore the monarchy.

However, the unstable situation in the country and the polarisation between communists and bourgeois allowed the monarchists to return to power after the parliamentary elections of March 1946. After becoming

In 1944, at the end of World War II, Nazi Germany gradually withdrew from Greece. While the majority of exiled Greeks were able to return to their country, the royal family had to remain in exile because of the growing republican opposition at home. Britain tried to reinstate George II, who remained in exile in London, but most of the resistance, in particular the communists, were opposed. Instead, George had to appoint from exile a Regency Council headed by Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens, who immediately appointed a republican-majority government headed by Nikolaos Plastiras. George, who was humiliated, ill and powerless, considered abdicating for a time in favour of his brother, but eventually decided against it.

Prince Paul, who was more combative but also more popular than his brother, would have liked to return to Greece as heir to the throne as early as the liberation of Athens in 1944, as he believed that back in his country he would have been quickly proclaimed regent, which would have blocked the way for Damaskinos and made it easier to restore the monarchy.

However, the unstable situation in the country and the polarisation between communists and bourgeois allowed the monarchists to return to power after the parliamentary elections of March 1946. After becoming

Constantine succeeded to the throne at a time when Greek society was experiencing economic and employment growth. Indicating his refusal to concede any power to the elected government, in September 1964, when there was yet no sign of his conflict with Papandreou, Constantine asked US Ambassador Henry Labouisse whether he "wanted him to get rid" of Papandreou, although he admitted he was not presently able to do so. The topic was discussed in subsequent conversations and in January 1965, before the emergence of the ASPIDA case, Cosntantine stated he considered inadvisable for the time being to adopt counsel he was receiving to clash with the Papandreou government due to the popular support it enjoyed. Political instability worsened in 1965. At a meeting with Papandreou that took place on 11 July 1965 in Korfu, Constantine requested that those implicated in the ASPIDA scandal, in which several military officials tried to prevent attempts by the extreme right-wing military to seize power, be referred to a military tribunal. Papandreou agreed and raised with him his intention to dismiss the then

Constantine succeeded to the throne at a time when Greek society was experiencing economic and employment growth. Indicating his refusal to concede any power to the elected government, in September 1964, when there was yet no sign of his conflict with Papandreou, Constantine asked US Ambassador Henry Labouisse whether he "wanted him to get rid" of Papandreou, although he admitted he was not presently able to do so. The topic was discussed in subsequent conversations and in January 1965, before the emergence of the ASPIDA case, Cosntantine stated he considered inadvisable for the time being to adopt counsel he was receiving to clash with the Papandreou government due to the popular support it enjoyed. Political instability worsened in 1965. At a meeting with Papandreou that took place on 11 July 1965 in Korfu, Constantine requested that those implicated in the ASPIDA scandal, in which several military officials tried to prevent attempts by the extreme right-wing military to seize power, be referred to a military tribunal. Papandreou agreed and raised with him his intention to dismiss the then

ΤΑ ΔΙΚΑ ΜΑΣ 60's – Μέρος 3ο: ΧΑΜΕΝΗ ΑΝΟΙΞΗ

" Stelios Kouloglu They asked Constantine to swear in the new government. Despite the detained Prime Minister Knellopoulos urging resistance, Constantine compromised with them to avoid bloodshed and in the afternoon swore in a new military government. He did, however, insist on appointing Supreme Court prosecutor Konstantinos Kollias as prime minister. On 26 April, in his speech on the new regime, he affirmed that "I am sure that with the will of God, with your efforts and above all with the help of the people, the organization of a State of Law, an authentic and healthy democracy". According to the then- US ambassador to Greece, Phillips Talbot, Constantine expressed his anger at this situation, revealed to him that he no longer had control of the army and claimed that "incredibly stupid extreme right-wing bastards with control of the tanks are leading Greece to destruction". From his inauguration as king, Constantine already manifested his disagreements with Archbishop Chrysostomos II of Athens. With the military dictatorship, he had the opportunity to be removed from the Greek Orthodox Cephaly, in fact it was one of the first measures with which Constantine collaborated with the Junta. On 28 April 1967, Chrysostomos II was retained and was forced to resign after having to sign one of the two versions of the letter brought to him by an official of the royal palace. Finally, Ieronymos Kotsonis was elected as metropolitan by the junta's and Constantine's proposal on 13 May 1967.

At the funeral of King Baudouin of Belgium, a private agreement was made between Constantine and the new conservative Greek prime minister,

At the funeral of King Baudouin of Belgium, a private agreement was made between Constantine and the new conservative Greek prime minister,

A long-standing dispute between the former royal family and the Greek state over the ownership of movable and immovable property which, prior to the constitutional change of the Metapolitefsi, was considered to be the property of King Constantine was resolved in 2002. The

A long-standing dispute between the former royal family and the Greek state over the ownership of movable and immovable property which, prior to the constitutional change of the Metapolitefsi, was considered to be the property of King Constantine was resolved in 2002. The

Constantine suffered multiple health problems in his final years, including heart conditions and decreased mobility. On 6 January 2023, he was admitted to the intensive care unit of the private Hygiea hospital in Athens in critical condition after suffering a stroke. He died 4 days later, on 10 January 2023, at the age of 82. His death was leaked by

Constantine suffered multiple health problems in his final years, including heart conditions and decreased mobility. On 6 January 2023, he was admitted to the intensive care unit of the private Hygiea hospital in Athens in critical condition after suffering a stroke. He died 4 days later, on 10 January 2023, at the age of 82. His death was leaked by

Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Redeemer (by birth)

** Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saints George and Constantine

**

Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Redeemer (by birth)

** Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saints George and Constantine

**  Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the

Official website of the Greek Royal Family

* * * *

ΜΑΡΙΟΣ ΠΛΩΡΙΤΗΣ:''Απάντηση στον Γκλύξμπουργκ'', Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, Κυριακή 10 Ιουνίου 2001 – Αρ. Φύλλου 13283

ΜΑΡΙΟΣ ΠΛΩΡΙΤΗΣ:''Δευτερολογία για τον Γκλύξμπουργκ'', Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, Κυριακή 24 Ιουνίου 2001 – Αρ. Φύλλου 13295

ΣΤΑΥΡΟΣ Π. ΨΥΧΑΡΗΣ: ''H ΣΥΝΤΑΓΗ ΤΗΣ ΚΡΙΣΗΣ'', Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, 17/10/2004 – Κωδικός άρθρου: B14292A011 ID: 265758

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constantine II of Greece 1940 births 2023 deaths Kings of Greece Eastern Orthodox monarchs 20th-century Greek monarchs 20th-century regents of Greece 21st-century Greek writers Nobility from Athens Greek junta Princes of Greece Princes of Denmark House of Glücksburg (Greece) Pretenders Field marshals of Greece Greek emigrants to England Greek International Olympic Committee members Greek male sailors (sport) Sailors at the 1960 Summer Olympics – Dragon Olympic sailors for Greece Soling class sailors Olympic gold medalists for Greece Royal Olympic medalists Members of the Church of Greece Grand Crosses of the Order of George I Grand Crosses of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece) Grand Crosses of the Order of Beneficence (Greece) Grand Commanders of the Order of the Dannebrog Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Italy) Knights Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Grand Crosses of the Order of the House of Orange Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Greek exiles Greek anti-communists Olympic medalists in sailing 1960s in Greek politics 20th-century Greek people Greek emigrants to Italy Medalists at the 1960 Summer Olympics Greek male karateka Greek people of Danish descent Sons of kings Greek autobiographers Burials at Tatoi Palace Royal Cemetery Exiled royalty Danish people of Greek descent Greek people of German descent Greek people of British descent Dethroned monarchs

King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach from 1832 to 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924 and, after being temporarily abolished in favor of the Second Hellenic Republic, again from 1935 to 1973, when it ...

, reigning from 6 March 1964 until the abolition of the Greek monarchy on 1 June 1973.

Constantine was born in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

as the only son of Crown Prince Paul and Crown Princess Frederica of Greece. Being of Danish descent, he was also born as a prince of Denmark. As his family was forced into exile during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he spent the first years of his childhood in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. He returned to Greece with his family in 1946 during the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

. After Constantine's uncle, George II, died in 1947, Paul became the new king and Constantine the crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

. As a young man, Constantine was a competitive sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship. While the term ''sailor'' ...

and Olympian, winning a gold medal

A gold medal is a medal awarded for highest achievement in a non-military field. Its name derives from the use of at least a fraction of gold in form of plating or alloying in its manufacture.

Since the eighteenth century, gold medals have b ...

in the 1960 Rome Olympics in the Dragon class along with Odysseus Eskitzoglou and George Zaimis in the yacht ''Nireus''. From 1964, he served on the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

.

Constantine acceded as king following his father's death in 1964. Later that year, he married Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, with whom he had five children. Although the accession of the young monarch was initially regarded auspiciously, his reign saw political instability that culminated in the Colonels' Coup of 21 April 1967. The coup left Constantine, as head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

, with little room to manoeuvre since he had no loyal military forces on which to rely. He thus reluctantly agreed to inaugurate the junta, on the condition that it be made up largely of civilian ministers. On 13 December 1967, Constantine was forced to flee the country, following an unsuccessful countercoup against the junta.

Constantine formally remained Greece's head of state in exile until the junta abolished the monarchy in June 1973, a decision ratified via a referendum in July, which was contested by Constantine. After the restoration of democracy a year later, another referendum was called for December 1974, but Constantine was not allowed to return to Greece to campaign. The referendum confirmed by a majority of almost 70% the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic. Constantine accepted the verdict of the 1974 vote. From 1975 until 1978 he was involved in conspiracies to overthrow the government via a coup, which eventually did not materialize. After living for several decades in London, Constantine moved back to Athens in 2013. He died there in 2023 following a stroke.

Early life

Constantine was born in the afternoon of 2 June 1940 at his parents' residence, Villa Psychiko at Leoforos Diamantidou 14 in Psychiko, an affluent suburb ofAthens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. He was the second child and only son of Crown Prince Paul and Crown Princess Frederica. His father was the younger brother and heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

of the reigning Greek king, George II, and his mother was the only daughter of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick, and Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia.

Prince Constantine had an elder sister, Princess Sofia, born in 1938. However, since agnatic primogeniture governed the succession to throne in Greece at the time, the birth of a male heir to the throne had been anxiously awaited by the Greek royal family, and the newborn prince was therefore received with joy by his parents. His birth was celebrated with a 101– gun salute from Mount Lycabettus in Athens, which, according to tradition, announced that the newborn was a boy. According to Greek naming practices, being the first son, he was named after his paternal grandfather, Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

, who had died in 1923. At his baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

on 20 July 1940 at the Royal Palace of Athens, the Hellenic Armed Forces acted as his godparent.

World War II and the exile of the royal family

Constantine was born during the early stages ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He was just a few months old when, on 28 October 1940, Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

invaded Greece from Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, beginning the Greco-Italian War. The Greek Army was able to halt the invasion temporarily and push the Italians back into Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

. However, the Greek successes forced Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

to intervene and the Germans invaded Greece and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

on 6 April 1941 and overran both countries within a month, despite British aid to Greece in the form of an expeditionary corps. On 22 April 1941, Princess Frederica and her two children, Sofia and Constantine, were evacuated to Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

in a British Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat Maritime patrol aircraft, patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

along with most of the Greek royal family. The next day, they were followed by King George II and Prince Paul. However the imminent German invasion of Crete quickly made the situation untenable and Constantine and his family were evacuated from Crete to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

on 30 April 1941, a fortnight before the German attack on the island. In Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, the exiled Greek royals were welcomed by the Greek diaspora, which provided them with lodging, money and clothing. The presence of the Greek royal family and government began to worry King Farouk of Egypt and his pro-Italian ministers. Constantine and his family, therefore, had to seek another refuge where they could get through the war and continue their fight against the Axis powers. George VI of the United Kingdom opposed the presence of Princess Frederica, who was suspected of having Nazi sympathies, and her children in Britain, but it was decided that Constantine's father and uncle could take up residence in London, where a government-in-exile was set up, while the rest of the family could seek refuge in the then-Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

.

On 27 June 1941, most of the Greek royal family, therefore, set off for South Africa on board the Dutch steamship ''Nieuw Amsterdam'', which arrived in Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

on 8 July 1941. After a two-month stay in Durban, Prince Paul left for England with his brother, and Constantine then barely saw his father again for the next three years. The rest of the family settled in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, where the family was joined by a younger sister, Princess Irene, born in 1942. Prince Constantine, Princess Sofia, their mother and their aunt Princess Katherine were initially lodged with South African Governor-General Patrick Duncan at his official residence Westbrooke in Cape Town.

The group subsequently moved several times until they settled in Villa Irene in Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

with Prime Minister Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

, who quickly became a close friend of the exiled Greeks. From early 1944, the family again took up residence in Egypt. In January 1944, Frederica was reunited with Paul in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, and their children joined them in March of that year. Despite their difficult financial circumstances, the family then established friendly relations with several Egyptian personalities, including Queen Farida, whose daughters were roughly the same age as Constantine and his sisters.

After World War II and return to Greece

In 1944, at the end of World War II, Nazi Germany gradually withdrew from Greece. While the majority of exiled Greeks were able to return to their country, the royal family had to remain in exile because of the growing republican opposition at home. Britain tried to reinstate George II, who remained in exile in London, but most of the resistance, in particular the communists, were opposed. Instead, George had to appoint from exile a Regency Council headed by Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens, who immediately appointed a republican-majority government headed by Nikolaos Plastiras. George, who was humiliated, ill and powerless, considered abdicating for a time in favour of his brother, but eventually decided against it.

Prince Paul, who was more combative but also more popular than his brother, would have liked to return to Greece as heir to the throne as early as the liberation of Athens in 1944, as he believed that back in his country he would have been quickly proclaimed regent, which would have blocked the way for Damaskinos and made it easier to restore the monarchy.

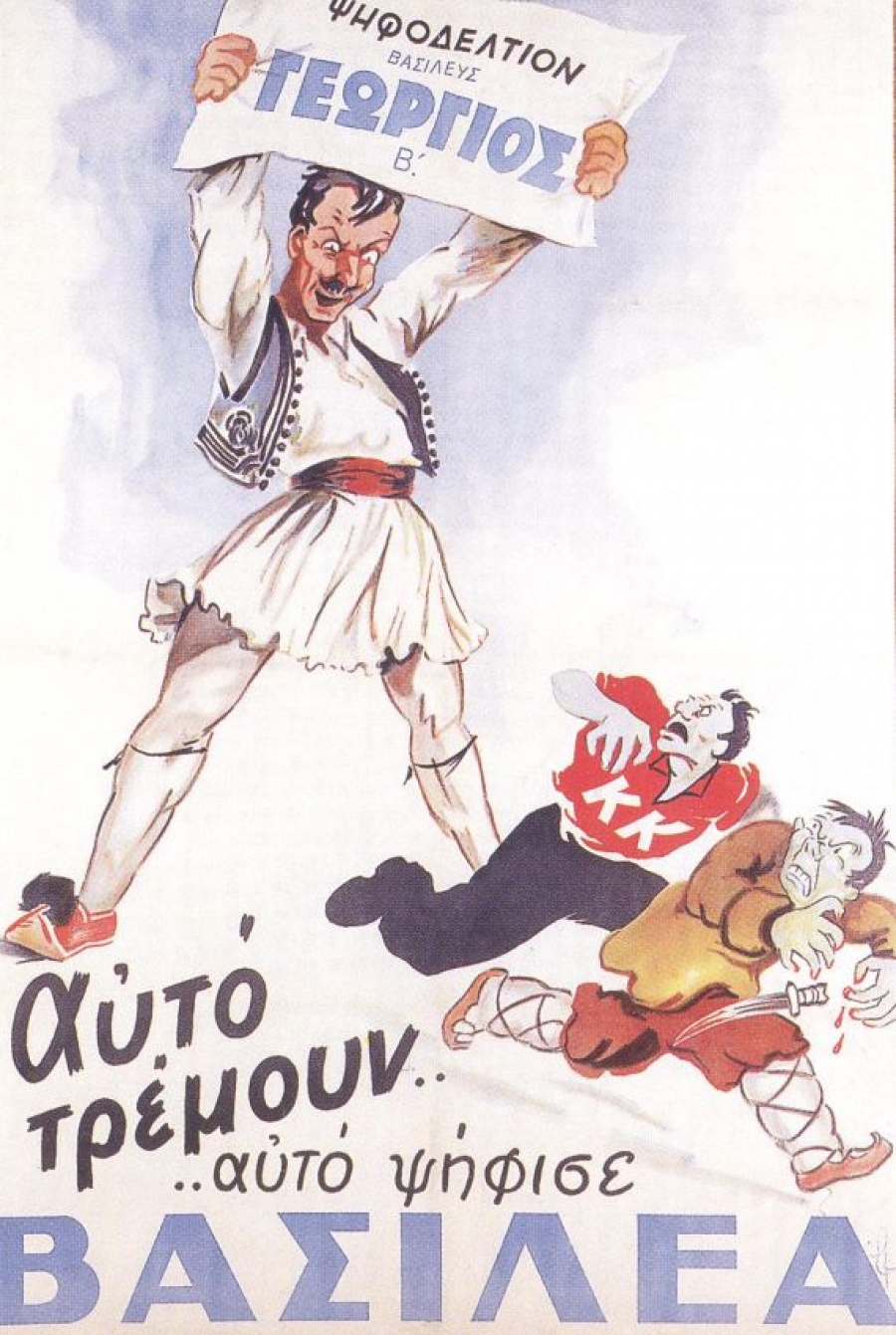

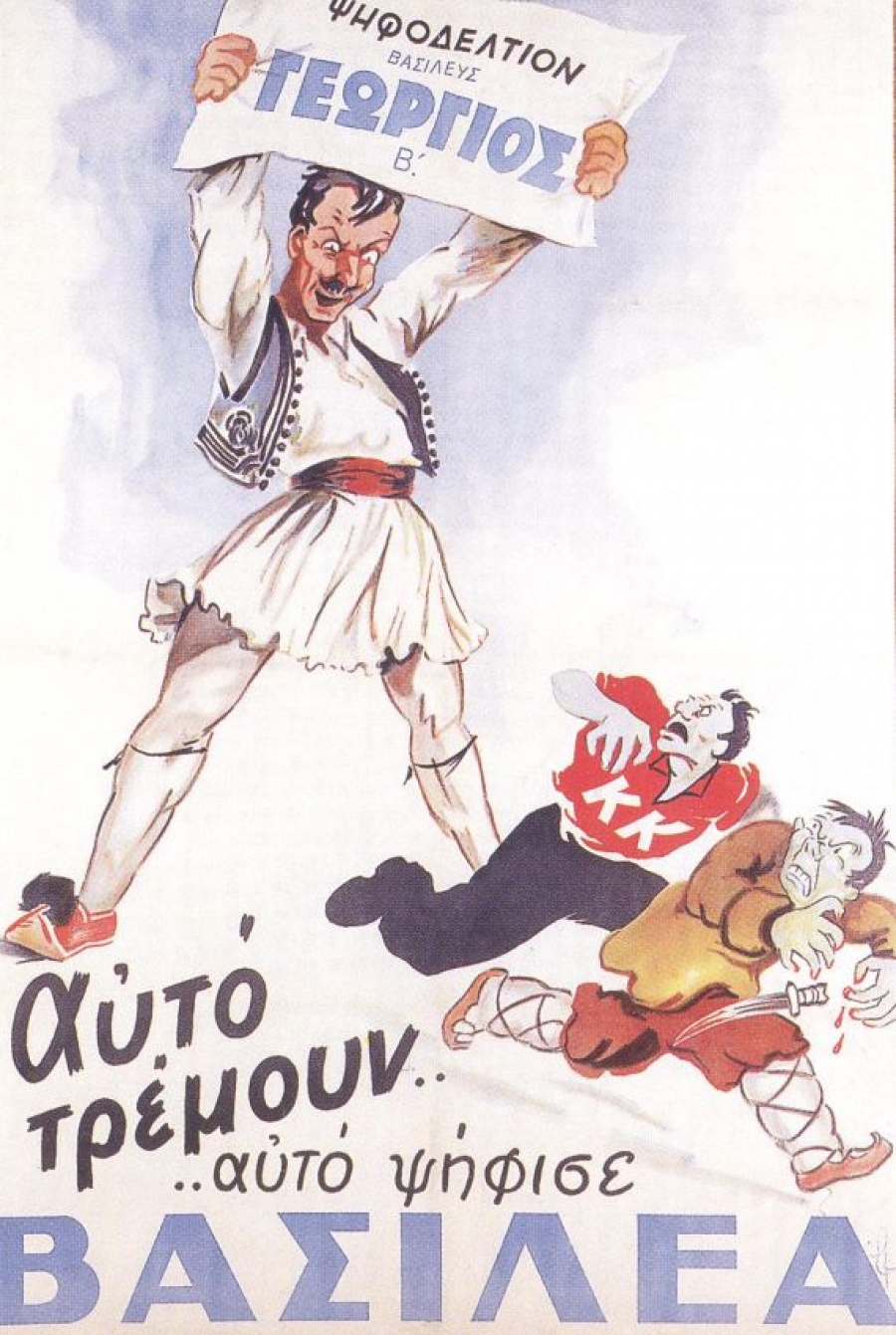

However, the unstable situation in the country and the polarisation between communists and bourgeois allowed the monarchists to return to power after the parliamentary elections of March 1946. After becoming

In 1944, at the end of World War II, Nazi Germany gradually withdrew from Greece. While the majority of exiled Greeks were able to return to their country, the royal family had to remain in exile because of the growing republican opposition at home. Britain tried to reinstate George II, who remained in exile in London, but most of the resistance, in particular the communists, were opposed. Instead, George had to appoint from exile a Regency Council headed by Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens, who immediately appointed a republican-majority government headed by Nikolaos Plastiras. George, who was humiliated, ill and powerless, considered abdicating for a time in favour of his brother, but eventually decided against it.

Prince Paul, who was more combative but also more popular than his brother, would have liked to return to Greece as heir to the throne as early as the liberation of Athens in 1944, as he believed that back in his country he would have been quickly proclaimed regent, which would have blocked the way for Damaskinos and made it easier to restore the monarchy.

However, the unstable situation in the country and the polarisation between communists and bourgeois allowed the monarchists to return to power after the parliamentary elections of March 1946. After becoming prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, Konstantinos Tsaldaris organised a referendum on 1 September 1946 with the aim of allowing George to return to the throne. The majority in the referendum was in favour of reinstating the monarchy, at which time Constantine and his family also returned to Greece. In a country still suffering from rationing and deprivation, they moved back to the villa in Psychikó. It was there that Paul and Frederica chose to start a small school, where Constantine and his sisters received their first education under the supervision of Jocelin Winthrop Young, a British disciple of the German-Jewish educator Kurt Hahn.

The tension between communists and conservatives led, in the following years, to the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

. That conflict was fought mainly in northern Greece. The Civil War ended in 1949, with the victory of the bourgeois and royalists, who had been supported by Britain and the United States.

Crown Prince

Education

During the Civil War, on 1 April 1947, George died. Thus, Constantine's father ascended the throne, and Constantine himself became Crown Prince of Greece at the age of six. He then moved with his family from the villa in Psychiko to Tatoi Palace at the foot of the Parnitha Mountains in the northern part of the Attica peninsula. The first years of Paul's reign did not bring great upheavals in his son's daily life. Constantine and his sisters were brought up relatively simply, and communication was at the heart of the pedagogy of their parents, who spent all the time they could with their children. Supervised by various British governesses and tutors, the children spoke English in the family but were also fluent in Greek. Until he was nine, Constantine continued to be educated with his sisters and other companions from Athens' wealthier population in the villa at Psychiko. After that age, Paul decided to begin preparing his son for the throne. He then started at the Anávryta lyceum inMarousi

Marousi or Maroussi (), also known as Amarousio (), is a city and a suburb in the northeastern part of the Athens#Athens Urban Area, Athens urban area, Greece. Marousi dates back to the era of the History of Athens, ancient Athenian Republic; its ...

, northeast of Athens, which also followed Kurt Hahn's pedagogy. He attended school there as a boarder between 1950 and 1958, while his sisters attended school in Salem, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. From 1955, Constantine served in all three branches of the Hellenic Armed Forces, attending the requisite military academies. He also attended the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

Air Force Special Weapons School in Germany, as well as the University of Athens

The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA; , ''Ethnikó kai Kapodistriakó Panepistímio Athinón''), usually referred to simply as the University of Athens (UoA), is a public university in Athens, Greece, with various campuses alo ...

, where he took courses in the school of law. In 1955, he received the title of Duke of Sparta.

Sailing and the Olympic Games

Constantine was an able sportsman. In 1958, Paul gave his son aLightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

class sailing boat for Christmas. Subsequently, Constantine spent most of his free time training with the boat on the Saronic Gulf. After a few months, the Greek Navy gave the prince a Dragon class sailing boat, with which he decided to participate in the 1960 Summer Olympics

The 1960 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XVII Olympiad () and commonly known as Rome 1960 (), were an international multi-sport event held from 25 August to 11 September 1960 in Rome, Italy. Rome had previously been awar ...

in Rome. At the opening of the Games in Rome, he was the flag bearer for the Greek team. He won an Olympic gold medal in the Dragon event, which was the first Greek gold medal since the Stockholm 1912 Summer Olympics

The 1912 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad () and commonly known as Stockholm 1912, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, between 6 July and 22 July 1912. The opening ceremony was he ...

. Constantine was the helmsman of their Olympic gold-winning sailing vessel ''Nireus'', and other members of the team included Odysseus Eskitzoglou and Georgios Zaimis.

Constantine was also a strong swimmer and had a black belt in karate, with interests in squash, track events, and riding. In 1963, Constantine became a member of the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

(IOC). He resigned in 1974 because he was no longer a Greek resident, and was made an honorary IOC member. He was an honorary member of the International Soling Association and president of the International Dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

Association.

Reign

Accession and marriage

In 1964, Paul's health deteriorated rapidly. He was diagnosed withstomach cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the Gastric mucosa, lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a numb ...

and underwent surgery for an ulcer

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughin ...

in February. Prior to this, Constantine had already been appointed regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

for his ailing father while waiting for his recovery. During his regency, Constantine limited himself to signing decrees and appointing members of the government, as well as accepting their resignations. As the king's condition worsened, the crown prince went to Tinos to attain an icon considered miraculous by the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Christianity in Greece, Greek Christianity, Antiochian Greek Christians, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christian ...

. On 6 March 1964, Paul died and the 23-year-old Constantine succeeded him as King of the Hellenes. The new king ascended the throne as Constantine II, although some of his supporters preferred to call him Constantine XIII to emphasize the continuity between the former Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

and the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

. On 23 March 1964, he was sworn in before the parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and was invested as chief of the armed forces with the highest ranks in each branch.

Due to his youth, Constantine was also perceived as a promise of change. Greece was still feeling the effects of the Civil War and society was strongly polarised between the royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

-conservative right wing and the liberal- socialist left wing. The accession of Constantine came shortly after the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

of centrist George Papandreou as prime minister in February 1964, which ended 11 years of right-wing rule by the National Radical Union (ERE). The Greek society hoped that the new king and the new prime minister would be able to overcome past dissensions. Later that year, on 18 September, Constantine married Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark in a Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

ceremony in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens. Anne-Marie was the youngest daughter of King Frederik IX, and she and Constantine were third cousins.

Apostasia of 1965

Constantine succeeded to the throne at a time when Greek society was experiencing economic and employment growth. Indicating his refusal to concede any power to the elected government, in September 1964, when there was yet no sign of his conflict with Papandreou, Constantine asked US Ambassador Henry Labouisse whether he "wanted him to get rid" of Papandreou, although he admitted he was not presently able to do so. The topic was discussed in subsequent conversations and in January 1965, before the emergence of the ASPIDA case, Cosntantine stated he considered inadvisable for the time being to adopt counsel he was receiving to clash with the Papandreou government due to the popular support it enjoyed. Political instability worsened in 1965. At a meeting with Papandreou that took place on 11 July 1965 in Korfu, Constantine requested that those implicated in the ASPIDA scandal, in which several military officials tried to prevent attempts by the extreme right-wing military to seize power, be referred to a military tribunal. Papandreou agreed and raised with him his intention to dismiss the then

Constantine succeeded to the throne at a time when Greek society was experiencing economic and employment growth. Indicating his refusal to concede any power to the elected government, in September 1964, when there was yet no sign of his conflict with Papandreou, Constantine asked US Ambassador Henry Labouisse whether he "wanted him to get rid" of Papandreou, although he admitted he was not presently able to do so. The topic was discussed in subsequent conversations and in January 1965, before the emergence of the ASPIDA case, Cosntantine stated he considered inadvisable for the time being to adopt counsel he was receiving to clash with the Papandreou government due to the popular support it enjoyed. Political instability worsened in 1965. At a meeting with Papandreou that took place on 11 July 1965 in Korfu, Constantine requested that those implicated in the ASPIDA scandal, in which several military officials tried to prevent attempts by the extreme right-wing military to seize power, be referred to a military tribunal. Papandreou agreed and raised with him his intention to dismiss the then minister of defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

, Petros Garoufalias, so that he could take charge himself of the ministry. Constantine refused, as the scandal wrongly implicated the prime minister's son, Andreas Papandreou

Andreas Georgiou Papandreou (, ; 5 February 1919 – 23 June 1996) was a Greek academic and economist who founded the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and served three terms as Prime minister of Greece, prime minister of Third Hellenic Repu ...

. After several clashes by letter between the monarch and the prime minister, Papandreou resigned on 15 July. Following the resignation, at least 39 members of Parliament left Center Union.

Constantine appointed a new government led by Georgios Athanasiadis-Novas, speaker of the parliament, which was formed by defectors disaffected with the Papandreous (the 'Apostates'). Soon, thousands of citizens took to the streets to protest against Constantine's decision, unprecedented protests that led to clashes with the Cities Police. On 21 July 1965, the protests in the centre of Athens came to a head, and in one of these clashes a policeman killed the 25-year-old student Sotiris Petroulas, leader of the student movement and of the "Lambrakis Youth". His death became a symbol of the protests and his funeral was widely attended. Due to Constantine's personal involvement and his clash with Papandreou, the protests -the largest, most persistent and combative since 1944- featured explicitly anti-monarchical slogans and the monarchy turned into a point of contention. Athanasiadis-Novas's government did not receive a vote of confidence from parliament and Athanasiadis-Novas resigned on 5 August 1965. The two big parties, National Radical Union and Center Union, asked Constantine to call elections, but he asked Stefanos Stefanopoulos to form a government. He then ordered Ilias Tsirimokos to form a government on 18 August but he did not receive the vote of confidence of the parliament on a vote on 28 August either. Constantine finally ordered Stefanopoulos to form a government and obtained the parliamentary confidence on 17 December 1965. An end to the crisis seemed in sight when on 20 December 1966, Papandreou, ERE leader Panagiotis Kanellopoulos and the king reached a resolution; elections would be held under a straightforward system of proportional representation where all parties participating agreed to compete, and that, in any outcome, the command structure of the army would not be altered. The third "apostate" government fell on 22 December 1966, and was succeeded by Ioannis Paraskevopoulos, who was to govern until the parliamentary elections of 28 May 1967, which were expected to favour a victory for Georgios Papandreou's Centre Union. Paraskevopoulos resigned and Kanellopoulos stepped in to fill the role of the Prime Minister on 3 April 1967 until the election.Clogg, 1987, pp. 53

Greek dictatorship of 1967–1974

Historians have suspected that Constantine and his mother were interested in a coup d'état from mid-1965 at the latest. US Army Attaché Charles Perkins reported that military right-wing group "Sacred Bond of Greek Officers" (IDEA) "plans for coup and military dictatorship in Greece", that Constantine was aware and that the group was aware that any operation in this direction with the cooperation of the US must have the permission of the king. According to Charilaos Lagoudakis, a US State Department expert on Greece, by mid-1966 Constantine had already approved a coup plan. On the other hand,Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

MP C.M. Woodhouse rejects as "certainly untrue" source evidence that in his talks with Talbot Constantine considered establishing a dictatorship, a stance that historian Mogens Pelt attributes to royalist Woodhouse's wish to salvage the king's reputation.

A traditionalist, right-wing nationalist group of middle-ranking army officers led by Colonel George Papadopoulos took action first and staged a coup d'état on 21 April using the fear of "communist danger" as the main reason for the coup. Tanks rolled through the streets of Athens, rifle shots were heard and military songs were played on the radio until the announcement that "The Hellenic Armed Forces have undertaken the governance of the country" was made public. Some high-ranking politicians were arrested, as well as the commander-in-chief of the army. The coup leaders met Constantine at his residence in Tatoi at about 7 a.m, which was surrounded by tanks to prevent resistance and the coup seemed to have succeeded bloodlessly. Constantine later recounted that the officers of the tank platoons believed they were carrying out the coup under his orders.TV documentaryΤΑ ΔΙΚΑ ΜΑΣ 60's – Μέρος 3ο: ΧΑΜΕΝΗ ΑΝΟΙΞΗ

" Stelios Kouloglu They asked Constantine to swear in the new government. Despite the detained Prime Minister Knellopoulos urging resistance, Constantine compromised with them to avoid bloodshed and in the afternoon swore in a new military government. He did, however, insist on appointing Supreme Court prosecutor Konstantinos Kollias as prime minister. On 26 April, in his speech on the new regime, he affirmed that "I am sure that with the will of God, with your efforts and above all with the help of the people, the organization of a State of Law, an authentic and healthy democracy". According to the then- US ambassador to Greece, Phillips Talbot, Constantine expressed his anger at this situation, revealed to him that he no longer had control of the army and claimed that "incredibly stupid extreme right-wing bastards with control of the tanks are leading Greece to destruction". From his inauguration as king, Constantine already manifested his disagreements with Archbishop Chrysostomos II of Athens. With the military dictatorship, he had the opportunity to be removed from the Greek Orthodox Cephaly, in fact it was one of the first measures with which Constantine collaborated with the Junta. On 28 April 1967, Chrysostomos II was retained and was forced to resign after having to sign one of the two versions of the letter brought to him by an official of the royal palace. Finally, Ieronymos Kotsonis was elected as metropolitan by the junta's and Constantine's proposal on 13 May 1967.

Royal countercoup of 13 December 1967 and exile

From the outset, the relationship between Constantine and the regime of the colonels was an uneasy one, especially when he refused to sign the decree imposingmartial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

and asked Talbot to flee Greece in an American helicopter with his family. But the administration of US president Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

wanted to keep Constantine in Greece to negotiate with the junta for the return of democracy. The presence of the United States Sixth Fleet

The Sixth Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy operating as part of United States Naval Forces Europe and Africa. The Sixth Fleet is headquartered at Naval Support Activity Naples, Italy. The officially stated mission of the Sixt ...

in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

outraged the junta government, which forced Constantine to get rid of his private secretary, . Arnaoutis, who had served as the king's military instructor in the 1950s and became his close friend, was generally reviled among the public for his role in the palace intrigues of the previous years. The junta, considering him an able and dangerous plotter, dismissed him from the army. The king and his entourage were beginning to worry that the future of the monarchy was endangered. Constantine visited the United States in the following days and in a meeting with Johnson, Constantine asked for military aid for a countercoup he was planning, but without success. The junta, however, had information about Constantine's conspiracy. Constantine later described himself as having the idea of a countercoup ten minutes after he found out about the junta's rise to power.

Constantine began negotiations with the officials loyal to him in the summer of 1967. His objective was to mobilise the units of the army loyal to him and to restore parliamentary legitimacy. The action was planned by Lieutenant General Konstantinos Dovas. Several military authorities joined the plan, including lieutenant general Antonakos, chief of the air force, Konstantinos Kollias, lieutenant general Kechagias, Ioannis Manettas, brigadier generals Erselman and Vidalis, major general Zalochoris, and others, so it was expected that the counterattack would be successful. The king communicated with Konstantinos Karamanlis, who was exiled in Paris and aware of the plot, and attempted to persuade him return to assume the post of prime minister if this movement was successful, but he refused. The main objective of the plan drawn up by the movement was that all the units initiated would occupy Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and the king would send a message to the public. It would follow the military operations in Tempi, Larissa and Lamia by the army and the swearing in of a new government by Archbishop Ieronymos with the participation of the centrist Georgios Mavros. Constantine and the involved officials began to realise that the plan could fail as they didn't count on the active support of American intelligence, who were aware of the details of the plan. They intended to initiate their plan on the day of a military parade scheduled for 28 October, but the junta-installed Chief of the Hellenic Army General Staff, Odysseas Angelis, refused to mobilise the units that Georgios Peridis requested. The abortive attempt, along with the visit of Constantine together with Peridis to some military divisions, were noted by the junta.

On the morning of the day the countercoup had been rescheduled to, 13 December 1967, after eight months of planning the countercoup, the royal family flew to Kavala, east of Thessaloniki, accompanied by Prime Minister Konstantinos Kollias who was informed at that moment of Constantine's plan. They arrived at 11:30 a.m. and were well received by the citizens. But some conspirators were neutralised, such as General Manettas, and Odysseas Angelis informed the public of the plan, asking citizens to obey his orders minutes before telecommunications were cut off. By noon, all the airbases, except one in Athens, had joined the royalist movement, and fleet leader Vice Admiral Dedes, before being arrested, ordered successfully the whole fleet sail towards Kavala in obedience to the king. They did not manage to take Thessaloniki and it soon became apparent that the senior officers were not in control of their units. This, along with the arrest of several officers, including the capture of Peridis that afternoon, and the delay in the execution of some orders, led to the countercoup's failure.

The junta, led by Georgios Papadopoulos, on the same day appointed General Georgios Zoitakis as Regent of Greece. Archbishop Ieronymos swore Zoitakis into office in Athens. Constantine, the royal family and Konstantinos Kollias took off in torrential rain from Kavala for exile in Rome, where they arrived at 4 p.m. on 14 December, with their plane having only five minutes of fuel left. In 2004, Constantine said that he would have done everything the same, but with more caution. Two weeks after his exile, photos of Constantine and his family celebrating Christmas with normality in the Greek Ambassador to Italy's home reached Greek media, which didn't do Constantine's reputation "any favour". He remained in exile in Italy through the rest of military rule, although he technically continued as king until 1 June 1973. He was never to return to Greece as a reigning monarch.

Constantine stated, "I am sure I shall go back the way my ancestors did." He said to the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part of Torstar's Daily News Brands (Torstar), Daily News Brands division.

...

'':

I consider myself King of the Hellenes and sole expression of legality in my country until the Greek people freely decide otherwise. I fully expected that the (military) regime would depose me eventually. They are frightened of the Crown because it is a unifying force among the people.Throughout the dictatorship, Constantine maintained contact with the junta, maintaining direct communication with the colonels and kept the royal subsidy until 1973. On 21 March 1972, Papadopoulos became Regent. At the end of May 1973, senior officers of the Greek navy organised an abortive coup to overthrow the junta government, but failed. The dictators considered Constantine to be involved, so on 1 June, with a constitutional act, Papadopoulos declared the monarchy abolished. He converted the country into a presidential and parliamentary state and assumed the interim presidency of the republic. In June 1973, Papadopoulos condemned Constantine as "a collaborator with foreign forces and with murderers" and accused him of "pursuing ambitions to become a political leader". The referendum of 29 July confirmed the end of the Greek monarchy and the end of the reign of Constantine. That year, the junta expropriated the palace of Tatoi and offered the king 120 million drachmas, money that Constantine refused.

Restoration of democracy and the referendum

TheTurkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

led to the downfall of the military regime, and Konstantinos Karamanlis returned from exile to become prime minister. The 1973 republican constitution was regarded as illegitimate, and the new administration issued a decree restoring the 1952 constitution. Constantine expected an invitation to return. On 24 July, he declared his "deep satisfaction with the initiative of the armed forces in overthrowing the dictatorial regime" and welcomed the advent of Karamanlis as prime minister.

Following the appointment of a civilian government in November 1974 after the first post-junta legislative election, Karamanlis called a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, held on 8 December 1974, on whether Greece would restore the monarchy or remain a republic. Although he had been the leader of the traditionally monarchist right, Karamanlis made no attempt to encourage a vote in favour of restoring the monarch. The king was not allowed by the government to return to Greece to campaign for the restoration of constitutional monarchy. He was only allowed to broadcast to the Greek people from London on television. Analysts claim this was a deliberate act by the government to reduce the possibility of a vote in favour of restoration.

Constantine, speaking from London, said he had made mistakes in the past. He said he would always be supportive of democracy in future and promised that his mother would stay away from the country. Local monarchists campaigned on his behalf. The vote to restore the monarchy was only about 31% with most of the support coming from the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

region. Almost 69% of the electorate voted against the restoration of the monarchy and for the establishment of a republic.

Post-reign

Constantine remained in exile for 40 years after the vote in favour of the republic, living in Italy and the United Kingdom. He returned briefly for the first time in February 1981, which was to attend the funeral of his mother in the family cemetery of the former Royal Palace at Tatoi. The funeral was generally controversial, due to the little empathy generated by Queen Frederica and the royal family, which is why the government authorized him to stay only for six hours in the country. His gesture of kissing the ground upon arrival in Greece was also polemic as it was considered an act of provocation for the antiroyalists.Abortive conspiracies

The posthumously published archives of Konstantinos Karamanlis, as well as the memoirs of Constantine's former marshal of the court, , revealed that from 1975 to 1978, Constantine was involved in a conspiracy to overthrow the democratic government, including the assassination of Karamanlis and a followed referendum on the monarchy. Constantine's close confidant, Michail Arnaoutis, approached high-ranking officers to try to gain their support. After some naval officers approached expressed doubts that Arnaoutis spoke for the former king, the chief engineer of the fleet was invited to London, where Constantine confirmed the basic outline of the plot as relayed by Arnaoutis. The naval officers approached informed Karamanlis, who sent Papagos to warn Constantine to "stop conspiring" and the former monarch denied knowledge of the conspiracy, but when called upon, Arnaoutis confirmed his contacts with officers in Greece in the presence of both Constantine and Papagos. The events were confirmed in 1999 by one of the officers whom Arnaoutis had approached, Vice Admiral Ioannis Vasileiadis, after the publication of Papagos' memoirs. According to Vasileiadis, Arnaoutis said that Constantine had contacted theShah of Iran

The monarchs of Iran ruled for over two and a half millennia, beginning as early as the 7th century BC and enduring until the 20th century AD. The earliest Iranian king is generally considered to have been either Deioces of the Median dynasty () ...

in order to prevent possible Turkish military action during the coup.

Karamanlis was also alerted to Constantine's suspicious activities by the British secret services, who had apparently taped his conversations with Greek visitors. In October 1976, the Greek prime minister was informed by the British ambassador that Constantine, while not the driving force behind the conspiracy, was very much aware of it and did nothing to discourage it. The British also provided warnings that sympathizers had informed Constantine that a coup would take place in November 1976, led by low-ranking army officers loyal to former dictator Dimitrios Ioannidis. Karamanlis and his chief diplomatic adviser, Petros Molyviatis, applied pressure on both the British and US governments, which led to a personal intervention by British prime minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

, who warned Constantine off. The Greek government repeatedly sent envoys to the former king for the same purpose, but he denied any knowledge of the affair. Karamanlis chose not to publicise it in order to not destabilise the fragile democratic system in Greece. Nevertheless, in October 1978, Constantine and Arnaoutis were recorded by Greek agents to have sought contact with military and political leaders, trying to win them over to the cause of a royal restoration.

Visits to Greece

12 February 1981

The first visit of Constantine and the former royal family to Greece took place on 12 February 1981, on the occasion of the funeral of his mother, Frederica. She had died in Madrid on 6 February, and it was the wish of both her and her descendants that she be buried next to her husband in the cemetery of Tatoi. As soon as Constantine's communication with the government of then Prime Minister George Rallis about the details of the funeral became known to the press, an intense political dispute erupted. Only six years had passed since the referendum and the controversies between the two sides - pro-royalist and anti-royalist - were still fresh. The opposition even raised the issue of a burial ban, a demand that was clearly illegal but indicative of the polarisation that existed. The Rallis government was therefore asked to find a compromise solution. Although the royal entourage's preference for a lay-in-state ceremony in Athens metropolitan cathedral followed by a burial in Tatoi, the Rallis government, in the midst of fierce confrontations with the opposition, decided that both the funeral and the burial should take place in Tatoi to avoid the possibility of violent clashes between pro- and anti-royal supporters. Constantine and his family could only stay on Greek soil for six hours, as long as they needed to carry out their duties. The former royal family arrived at Ellinikon airport and Constantine disembarked, bent down and kissed the ground. This token gesture added new fuel to the controversy, with some interpreting it as genuine love of country and others as hypocrisy. The funeral and burial took place under police protection. However, the police were unable to keep the crowds of supporters of the former king away from the site.August 1993

At the funeral of King Baudouin of Belgium, a private agreement was made between Constantine and the new conservative Greek prime minister,

At the funeral of King Baudouin of Belgium, a private agreement was made between Constantine and the new conservative Greek prime minister, Konstantinos Mitsotakis

Konstantinos Mitsotakis (, ; – 29 May 2017) was a Greek politician who was Prime Minister of Greece from 1990 to 1993. He graduated in law and economics from the University of Athens. His son, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, was elected as the Prime Mi ...

, that allowed Constantine and his family to temporarily return to Greece on a holiday. Constantine was accompanied by his wife Anne-Marie, their five children, and his sister Irene. The family had decided that yachting around Greece would be the best way to showcase the country to their children, who were unable to grow up within Greece. The opposition claimed that the government was attempting to reinstate the monarchy. On 9 August 1993, the family departed from the UK on two planes, including a jet donated to Constantine by King Hussein of Jordan

Hussein bin Talal (14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 1952 until Death and state funeral of King Hussein, his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemites, Hashemite dynasty, the royal family of Jordan since 1921, Hu ...

. The Greek government was unaware of Constantine and his family's holiday, which had been planned and charted by Princess Alexia. Constantine, and then his family a few hours later, landed in Thessaloniki, before boarding a yacht.

The family's yacht then travelled 300 metres off the shore of Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

. Constantine and his two eldest sons, Crown Prince Pavlos and Prince Nikolaos, travelled upon a dinghy to get to the mainland, where women were not allowed to visit. Upon arriving, Constantine noticed his portrait in every monastery and learnt that the monks there had been praying for him every day since his exile. Nine monks followed Constantine back to their yacht to bless the rest of his family, display holy relics and present gifts. Constantine then took a helicopter and landed on a soccer pitch in Florina

Florina (, ''Flórina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the Florina regional uni ...

, where "hundreds" of people greeted him with handshakes and flowers. Constantine's decision to land in Florina was named a "politically sensitive spot to appear in" in view of the region's greater support for the monarchy over other regions and due to the Macedonia naming dispute

The use of the country name "Macedonia (terminology), Macedonia" was disputed between Greece and the North Macedonia, Republic of Macedonia (now North Macedonia) between 1991 and 2019. The dispute was a source of instability in the Balkans#W ...

. Constantine and his family took a van north in order see the northernmost part of Greece, and were reportedly followed by between 50 and 100 cars. However, the Greek government had organised for the police to block the road, claiming that Constantine's journey was "a political step", rather than touristic. Protestors attempted to open up the road, but failed. In the next village the family stopped at, a local government official told Constantine that he would be kicked out of Greece if he did not act like a tourist.

Following this clash between police and protestors in support of Constantine, Mitsotakis made a public statement explaining that the government "had no prior knowledge of the visit and had never agreed to it. Strong action will be taken if the ex-king violates our conditions." Afterwards, Constantine and his family returned to Athens to visit Tatoi Palace and his parents' graves, where a short memorial service was held. During this trip, Constantine chose where his future tomb would be. Telling Sky News

Sky News is a British free-to-air television news channel, live stream news network and news organisation. Sky News is distributed via an English-language radio news service, and through online channels. It is owned by Sky Group, a division of ...

presenter Selina Scott, Constantine said that having to leave his belongings when going into exile taught him that "material things are not that important". He also expressed his wishes to move back into the property and clean up the land surrounding it. Constantine was then warned by the government to move on from Tatoi and alerted them of protestors who were threatening to burn Tatoi's forestry down.

Whilst travelling to Spetses, the government ordered that Constantine should not travel to heavily populated areas, to which Constantine said, "It's a free country". When he arrived at a port in Spetses, a harbour policeman jumped onto their boat, but Constantine pushed him to the side and set foot on the mainland. A crowd greeted Constantine and his family, but at night and during the following day, their yacht was surrounded by government ships and flown over by military planes. Constantine then contacted Sky News UK and was interviewed by presenter David Blaine, to whom Constantine told on live air that he was being harassed by the government, who had "frightened the daylights" out of his children. Constantine's yacht was on course to stop at Gytheio, where a reported 5,000 to 10,000 people were waiting for him. Military warships were denying the yacht's progress towards the town, so Constantine stopped in Neapoli Voion, where there was a crowd of a few hundred people, but also many anti-monarchists. Following this stop, Constantine and his family returned to the UK.

Legal quarrels over the royal properties

Properties and citizenship

A long-standing dispute between the former royal family and the Greek state over the ownership of movable and immovable property which, prior to the constitutional change of the Metapolitefsi, was considered to be the property of King Constantine was resolved in 2002. The

A long-standing dispute between the former royal family and the Greek state over the ownership of movable and immovable property which, prior to the constitutional change of the Metapolitefsi, was considered to be the property of King Constantine was resolved in 2002. The European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a co ...

condemned Greece for violating Article 1 of the First Protocol and awarded the former royal family compensation of €13.7 million.According to Evangelos Venizelos "The Strasbourg judgment accepts that Tatoi Palace, Mon Repos, Corfu and Royal estate of Polydendri constitute the individual property of the applicants. It accepts that Law No. 2215/1994 is in conformity with the Greek Constitution and that it constitutes the legal basis for the valid expropriation of such property for sufficient reasons of public interest. It requests, however, that an adequate or, rather, "some" compensation be determined for the applicants, since their rights under Article 1 of the Additional Protocol to the ECHR have been violated." The legal basis of the dispute was determined by the interpretation of royal property as private or public. According to the royal family, the property was acquired by their predecessors through legal means (purchases) from their personal estates and was therefore considered the inheritance of the former king. In the eyes of the Greek public, however, the property was a by-product of the institution of the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

and served to enable the supreme ruler to exercise his role as monarch. With the demise of the monarchy, the property should automatically pass to the state.

In 1973, Decree No. 225 expropriated the movable and immovable property of the former king and members of the royal family for the benefit of the state. In September 1974, the government of National Salvation, headed by Constantine Karamanlis revoked the junta's decree in anticipation of the referendum that would determine the country's constitution. Although the referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

abolished the monarchy, the government did not proceed with the confiscation of property. Instead, it set up a seven-member commission to administer the property. This committee later handed over its responsibilities to the legal representative of the royal family in Greece, retired admiral Mario Stavridis. Thus, members of the royal family continued to declare their property as inherited and to file inheritance and income tax returns, and the tax administration continued to assess taxes and impose surcharges and fines. In 1984, Constantine took the initiative to approach the Greek government to settle the former royal family's tax debts to the Greek state. An agreement was finally reached in 1992, under the government of Konstantinos Mitsotakis

Konstantinos Mitsotakis (, ; – 29 May 2017) was a Greek politician who was Prime Minister of Greece from 1990 to 1993. He graduated in law and economics from the University of Athens. His son, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, was elected as the Prime Mi ...

with Law 2086/1992. The agreement - which was never implemented - included the payment by the royal family of 183,000,000 drachmas

Drachma may refer to:

* Ancient drachma, an ancient Greek currency

* Modern drachma, a modern Greek currency (1833...2002)

* Cretan drachma, currency of the former Cretan State

* Drachma proctocomys, moth species, the only species in the Genus '' ...

in cash from the total amount of inheritance tax

International tax law distinguishes between an estate tax and an inheritance tax. An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and pro ...

due, while the rest was to be covered by the concession of 200 acres to the state, 400 acres to the "World Hippocratic Hospital Foundation and Research Centre" to be built a huge hospital complex, and 37,426 acres to the "Tatoi National Park". In the agreement there was no specific provision for the so-called "summer palace" of Tatoi, for Mon Repo, for Polydendri and for mobile things. All these were considered the King's property.

In 1993, on the occasion of the visit of the royal family to Greece, Andreas Papandreou

Andreas Georgiou Papandreou (, ; 5 February 1919 – 23 June 1996) was a Greek academic and economist who founded the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and served three terms as Prime minister of Greece, prime minister of Third Hellenic Repu ...

announced the legislative settlement of the outstanding issues. In fact, on the basis of the consultative document drafted by Evangelos Venizelos for the Municipality of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

to strengthen their claim to Mon Repos, when PASOK

The Panhellenic Socialist Movement (, ), known mostly by its acronym PASOK (; , ), is a social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Greece, political party in Greece. Until 2012 it was Two-party system, one of the two major ...

returned to power under, it abolished the previous law and replaced it with 2215/1994. The Law confiscated the King's property for the benefit of the state without the right to compensation and deprived the members of the royal family of their Greek citizenship. The royal family immediately appealed to the country's civil courts. Although upheld by the Supreme Civil and Criminal Court of Greece, the decision was overturned by the Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

. The Special Highest Court, to which the case was referred in 1997, agreed with the Council of State. All legal remedies in Greece had been depleted. The royal family therefore turned to the European courts.

An appeal to the European Commission of Human Rights

The European Commission of Human Rights was a special body of the Council of Europe.

From 1954 to the 1998 entry into force of European Convention on Human Rights#Protocol 11, Protocol 11 to the European Convention on Human Rights, individuals d ...

was lodged by Constantine, Anna-Marie, their five children, Princess Irene and Princess Catherine. His sister, Queen Sophia, did not take part because she had already renounced her rights to the estate. The court allowed the appeal, but only for Constantine, Irene and Catherine. In October 1998, the European Commission admitted the property issue when all 30 judges unanimously ruled that human rights had been violated and referred the matter to the European Court of Human Rights. Constitutional lawyer Nikos Alivizatos, a member of the team of lawyers who represented the Greek State in the trial, pointed out that the trial was considered historic, as it was the most important property case to come before them. The former royal family challenged the expropriation without compensation of 42,000 acres in Tatoi, 230 acres in Corfu and 33,000 acres in Polydendri, Larissa. The total amount demanded by the former king was 168.7 billion drachmas. The court also encouraged six months of meetings between Constantine and the Greek government to coordinate a settlement, however the Greek government refused. The court also defined the former king's litigation assets as private, ruling that the property that accompanied the institution of the monarchy had already been automatically transferred to the state, meaning that the Greek state could award Constantine monetary compensation, rather than returning his royal properties.as property arising from the office of monarch, were transferred to the state, Royal Palace of Psychiko, Presidential Mansion, Athens and Palataki (Thessaloniki) The Greek State was therefore obliged to compensate the plaintiffs, setting the appropriate compensation at 1/40th of the amount claimed, i.e. 4.7 billion

Billion is a word for a large number, and it has two distinct definitions:

* 1,000,000,000, i.e. one thousand million, or (ten to the ninth power), as defined on the short scale. This is now the most common sense of the word in all varieties of ...

drachmas (13.7 million euro

The euro (currency symbol, symbol: euro sign, €; ISO 4217, currency code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Union. This group of states is officially known as the ...