Congo Free State on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

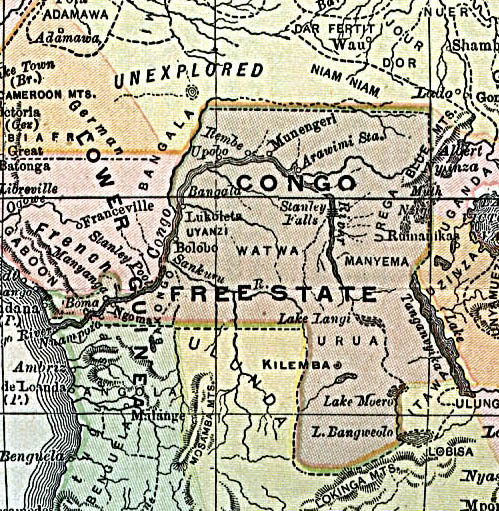

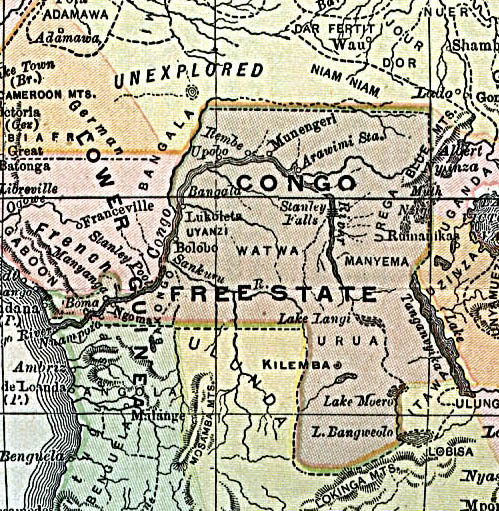

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large

Leopold began to create a plan to convince other European powers of the legitimacy of his claim to the region, all the while maintaining the guise that his work was for the benefit of the native peoples under the name of a philanthropic "association".

The king launched a publicity campaign in Britain to distract critics, drawing attention to Portugal's record of slavery, and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same

Leopold began to create a plan to convince other European powers of the legitimacy of his claim to the region, all the while maintaining the guise that his work was for the benefit of the native peoples under the name of a philanthropic "association".

The king launched a publicity campaign in Britain to distract critics, drawing attention to Portugal's record of slavery, and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same

In November 1884,

In November 1884,

Leopold no longer needed the façade of the ''association'', and replaced it with an appointed cabinet of Belgians who would do his bidding. To the temporary new capital of Boma, he sent a governor-general and a chief of police. The vast

Leopold no longer needed the façade of the ''association'', and replaced it with an appointed cabinet of Belgians who would do his bidding. To the temporary new capital of Boma, he sent a governor-general and a chief of police. The vast

Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State. Desperately, he set in motion a system to maximize revenue. The first change was the introduction of the concept of ''terres vacantes'', "vacant" land, which was any land that did not contain a habitation or a cultivated garden plot. All of this land (i.e., most of the country) was therefore deemed to belong to the state. Servants of the state (namely any men in Leopold's employ) were encouraged to exploit it.

Shortly after the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference (1889–1890), Leopold issued a new decree mandating that Africans in a large part of the Free State could sell their harvested products (mostly ivory and rubber) only to the state. This law extended an earlier decree declaring that all "unoccupied" land belonged to the state. Any ivory or rubber collected from the state-owned land, the reasoning went, must belong to the state, thus creating a de facto state-controlled monopoly. Therefore, a large share of the local population could sell only to the state, which could set prices and thereby control the income the Congolese could receive for their work. For local elites, however, this system presented new opportunities, as the Free State and concession companies paid them with guns to tax their subjects in kind.

Trading companies began to lose out to the Free State government, which not only paid no taxes but also collected all the potential income. These companies were outraged by the restrictions on free trade, which the Berlin Act had so carefully protected years before. Their protests against the violation of free trade prompted Leopold to take another, less obvious tack to make money.

Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State. Desperately, he set in motion a system to maximize revenue. The first change was the introduction of the concept of ''terres vacantes'', "vacant" land, which was any land that did not contain a habitation or a cultivated garden plot. All of this land (i.e., most of the country) was therefore deemed to belong to the state. Servants of the state (namely any men in Leopold's employ) were encouraged to exploit it.

Shortly after the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference (1889–1890), Leopold issued a new decree mandating that Africans in a large part of the Free State could sell their harvested products (mostly ivory and rubber) only to the state. This law extended an earlier decree declaring that all "unoccupied" land belonged to the state. Any ivory or rubber collected from the state-owned land, the reasoning went, must belong to the state, thus creating a de facto state-controlled monopoly. Therefore, a large share of the local population could sell only to the state, which could set prices and thereby control the income the Congolese could receive for their work. For local elites, however, this system presented new opportunities, as the Free State and concession companies paid them with guns to tax their subjects in kind.

Trading companies began to lose out to the Free State government, which not only paid no taxes but also collected all the potential income. These companies were outraged by the restrictions on free trade, which the Berlin Act had so carefully protected years before. Their protests against the violation of free trade prompted Leopold to take another, less obvious tack to make money.

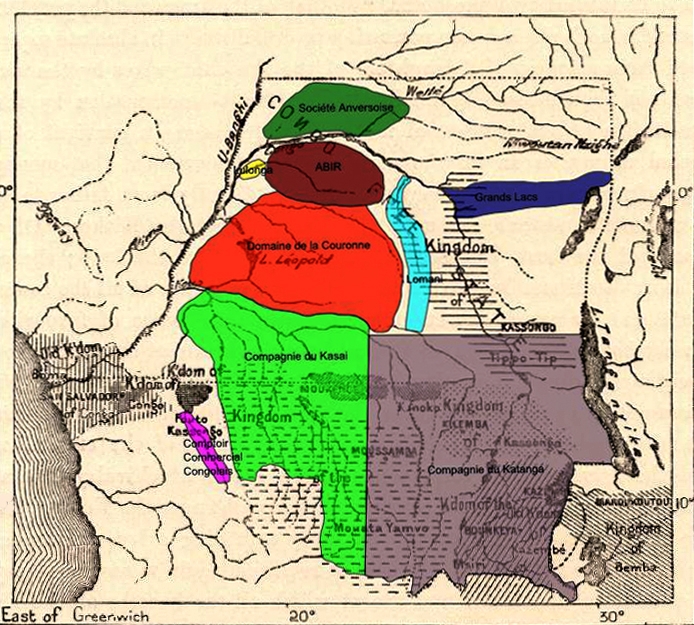

A decree in 1892 divided the ''terres vacantes'' into a domainal system that privatized extraction rights over rubber for the state in certain private domains, allowing Leopold to grant vast concessions to private companies. In other areas, private companies could continue to trade but were highly restricted and taxed. The domainal system enforced an in-kind tax on the Free State's Congolese subjects. As essential intermediaries, local rulers forced their men, women and children to collect rubber, ivory and foodstuffs. Depending on the power of local rulers, the Free State paid prices below the rising market prices. In October 1892, Leopold granted concessions to a number of companies. Each company was given a large amount of land in the Congo Free State on which to collect rubber and ivory for sale in Europe. These companies were allowed to detain Africans who did not work hard enough, to police their vast areas as they saw fit and to take all the products of the forest for themselves. In return for their concessions, these companies paid an annual dividend to the Free State. At the height of the rubber boom, from 1901 until 1906, these dividends also filled the royal coffers.

The Free Trade Zone in the Congo was open to entrepreneurs of any European nation, who were allowed to buy 10- and 15-year monopoly leases on anything of value: ivory from a district or the rubber concession, for example. The other zone—almost two-thirds of the Congo—became the ''Domaine Privé'', the exclusive private property of the state.

In 1893, Leopold excised the most readily accessible portion of the Free Trade Zone and declared it to be the ''Domaine de la Couronne'', literally, "fief of the crown". Rubber revenue went directly to Leopold who paid the Free State for the high costs of exploitation. The same rules applied as in the ''Domaine Privé''. In 1896 global demand for rubber soared. From that year onwards, the Congolese rubber sector started to generate vast sums of money at an immense cost for the local population.

A decree in 1892 divided the ''terres vacantes'' into a domainal system that privatized extraction rights over rubber for the state in certain private domains, allowing Leopold to grant vast concessions to private companies. In other areas, private companies could continue to trade but were highly restricted and taxed. The domainal system enforced an in-kind tax on the Free State's Congolese subjects. As essential intermediaries, local rulers forced their men, women and children to collect rubber, ivory and foodstuffs. Depending on the power of local rulers, the Free State paid prices below the rising market prices. In October 1892, Leopold granted concessions to a number of companies. Each company was given a large amount of land in the Congo Free State on which to collect rubber and ivory for sale in Europe. These companies were allowed to detain Africans who did not work hard enough, to police their vast areas as they saw fit and to take all the products of the forest for themselves. In return for their concessions, these companies paid an annual dividend to the Free State. At the height of the rubber boom, from 1901 until 1906, these dividends also filled the royal coffers.

The Free Trade Zone in the Congo was open to entrepreneurs of any European nation, who were allowed to buy 10- and 15-year monopoly leases on anything of value: ivory from a district or the rubber concession, for example. The other zone—almost two-thirds of the Congo—became the ''Domaine Privé'', the exclusive private property of the state.

In 1893, Leopold excised the most readily accessible portion of the Free Trade Zone and declared it to be the ''Domaine de la Couronne'', literally, "fief of the crown". Rubber revenue went directly to Leopold who paid the Free State for the high costs of exploitation. The same rules applied as in the ''Domaine Privé''. In 1896 global demand for rubber soared. From that year onwards, the Congolese rubber sector started to generate vast sums of money at an immense cost for the local population.

Early in Leopold's rule, the second problem—the British South Africa Company's expansion into the southern Congo Basin—was addressed. The distant Yeke Kingdom, in Katanga on the upper

Early in Leopold's rule, the second problem—the British South Africa Company's expansion into the southern Congo Basin—was addressed. The distant Yeke Kingdom, in Katanga on the upper

published 1892 in: Edouard Charton (editor): ''Le Tour du Monde'' magazine, website accessed 5 May 2007.

In 1894, King Leopold II signed a treaty with the United Kingdom which conceded a strip of land on the Free State's eastern border in exchange for the

In 1894, King Leopold II signed a treaty with the United Kingdom which conceded a strip of land on the Free State's eastern border in exchange for the

While the war against African powers was ending, the quest for income was increasing, fuelled by the aire policy. By 1890, Leopold was facing considerable financial difficulty. District officials' salaries were reduced to a bare minimum, and made up with a commission payment based on the profit that their area returned to Leopold. After widespread criticism, this "primes system" was substituted for the ''allocation de retraite'' in which a large part of the payment was granted, at the end of the service, only to those territorial agents and magistrates whose conduct was judged "satisfactory" by their superiors. This meant in practice that nothing changed. Congolese communities in the ''Domaine Privé'' were not merely forbidden by law to sell items to anyone but the state; they were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

In direct violation of his promises of free trade within the CFS under the terms of the Berlin Treaty, not only had the state become a commercial entity directly or indirectly trading within its dominion, but also, Leopold had been slowly monopolizing a considerable amount of the ivory and rubber trade by imposing export duties on the resources traded by other merchants within the CFS. In terms of infrastructure, Leopold's regime began construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). The railway, now known as the

While the war against African powers was ending, the quest for income was increasing, fuelled by the aire policy. By 1890, Leopold was facing considerable financial difficulty. District officials' salaries were reduced to a bare minimum, and made up with a commission payment based on the profit that their area returned to Leopold. After widespread criticism, this "primes system" was substituted for the ''allocation de retraite'' in which a large part of the payment was granted, at the end of the service, only to those territorial agents and magistrates whose conduct was judged "satisfactory" by their superiors. This meant in practice that nothing changed. Congolese communities in the ''Domaine Privé'' were not merely forbidden by law to sell items to anyone but the state; they were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

In direct violation of his promises of free trade within the CFS under the terms of the Berlin Treaty, not only had the state become a commercial entity directly or indirectly trading within its dominion, but also, Leopold had been slowly monopolizing a considerable amount of the ivory and rubber trade by imposing export duties on the resources traded by other merchants within the CFS. In terms of infrastructure, Leopold's regime began construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). The railway, now known as the  The ''

The ''

StoryoftheCongoFreeState 172b.jpg, Congolese people working at the port of Leopoldville

StoryoftheCongoFreeState 382.jpg, Construction of a railroad by Congolese workers

StoryoftheCongoFreeState 412.jpg, Melting latex of rubber in the forest of

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and absolute monarchy in Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by King Leopold II, the constitutional monarch

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

of the Kingdom of Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southe ...

. In legal terms, the two separate countries were in a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

. The Congo Free State was not a part of, nor did it belong to, Belgium. Leopold was able to seize the region by convincing other Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an states at the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

on Africa that he was involved in humanitarian and philanthropic work and would not tax trade. Via the International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Congo. It replaced the Belgian Committee for S ...

, he was able to lay claim to most of the Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

. On 29 May 1885, after the closure of the Berlin Conference, the king announced that he planned to name his possessions "the Congo Free State", an appellation which was not yet used at the Berlin Conference and which officially replaced "International Association of the Congo" on 1 August 1885. The Free State was privately controlled by Leopold from Brussels; he never visited it.

The state included the entire area of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

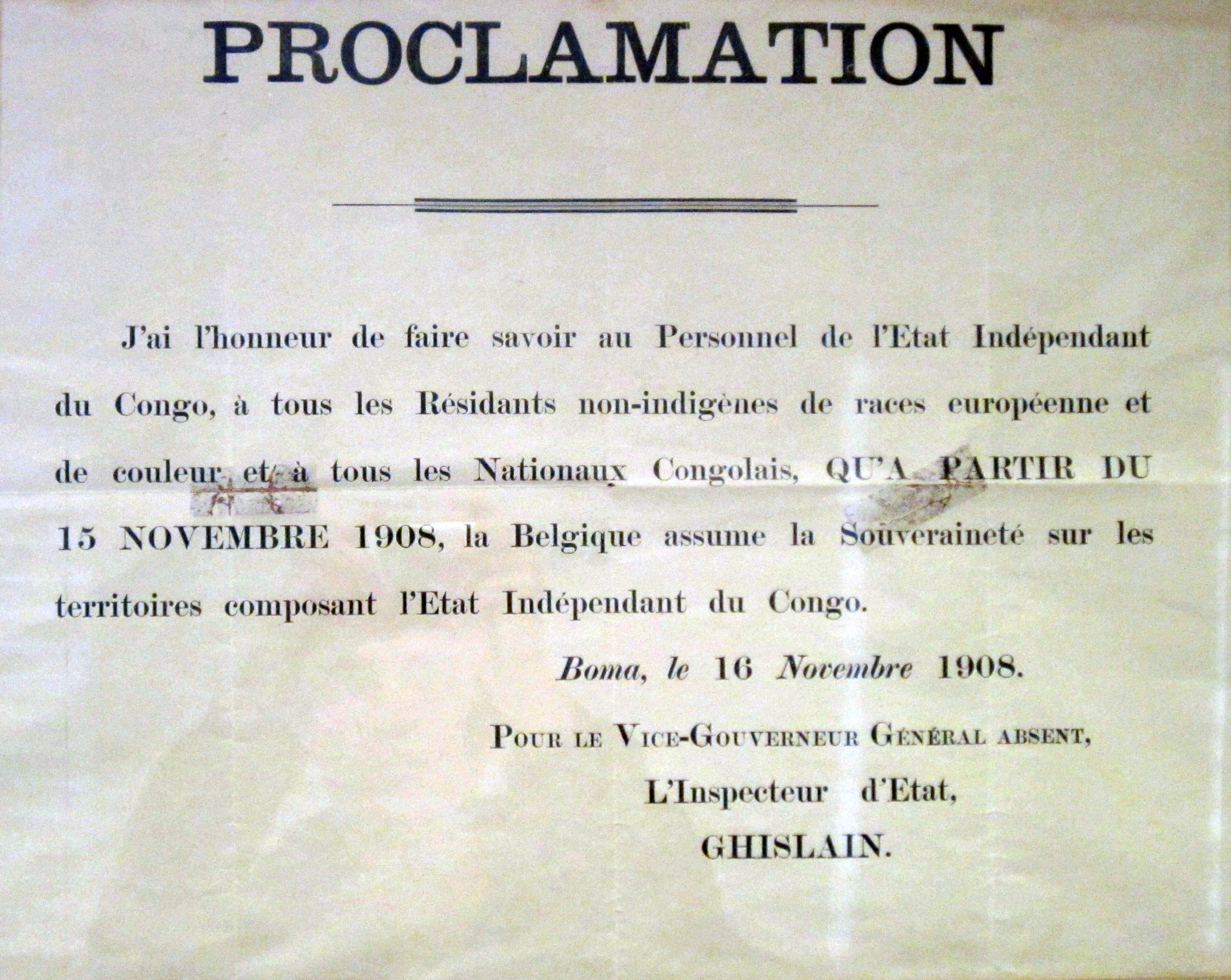

and existed from 1885 to 1908, when the Belgian Parliament reluctantly annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

the state as a colony belonging to Belgium after international pressure.Britannica:

Leopold's reign in the Congo eventually earned infamy on account of the atrocities perpetrated on the locals. Ostensibly, the Congo Free State aimed to bring civilization to the local people and to develop the region economically. In reality, Leopold II's administration extracted ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

, rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

, and minerals from the upper Congo basin for sale on the world market through a series of international concessionary companies that brought little benefit to the area. Under Leopold's administration, the Free State became one of the greatest international scandals of the early 20th century. The Casement Report

The Casement Report was a 1904 document written at the behest of the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government by Roger Casement (1864–1916)—a British diplomat and future Irish War of Independence, Irish independence fighter—detai ...

of the British Consul Roger Casement

Roger David Casement (; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during World War I. He worked for the Britis ...

led to the arrest and punishment of officials who had been responsible for killings during a rubber-collecting expedition in 1903.

The loss of life and atrocities inspired literature such as Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

's novel ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' is an 1899 novella by Polish-British novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgium, Belgian company in the African interior. Th ...

'' and raised an international outcry. Debate has been ongoing about the high death rate in this period. The highest estimates state that the widespread use of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

, torture, and murder led to the deaths of 50 per cent of the population in the rubber provinces. The lack of accurate records makes it difficult to quantify the number of deaths caused by the exploitation and the lack of immunity to new diseases introduced by contact with European colonists. During the Congo Free State propaganda war

The Congo Free State propaganda war was a worldwide media propaganda campaign waged by both King Leopold II of Belgium and the critics of the Congo Free State and its Atrocities in the Congo Free State, atrocities. Leopold was very astute in usin ...

, European and US reformers exposed atrocities in the Congo Free State to the public through the Congo Reform Association, founded by Casement and the journalist, author, and politician E. D. Morel. Also active in exposing the activities of the Congo Free State was the author Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

, whose book '' The Crime of the Congo'' was widely read in the early 1900s.

By 1908, public pressure and diplomatic manoeuvres led to the end of Leopold II's absolutist rule; the Belgian Parliament annexed the Congo Free State as a colony of Belgium. It became known thereafter as the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

. In addition, a number of major Belgian investment companies pushed the Belgian government to take over the Congo and develop the mining sector as it was virtually untapped.

Background

Early European exploration

Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão (; – 1486), also known as Diogo Cam, was a Portuguese mariner and one of the most notable explorers of the fifteenth century. He made two voyages along the west coast of Africa in the 1480s, exploring the Congo River and the coasts ...

travelled around the mouth of the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

in 1482, leading Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

to claim the region. Until the middle of the 19th century, the Congo was at the heart of independent Africa, as European colonialists seldom entered the interior. Along with fierce local resistance, the rainforest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

, swamps, malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is caused by the species '' Trypanosoma b ...

, and other diseases made it a difficult environment for Europeans to settle. Western states were at first reluctant to colonize the area in the absence of obvious economic benefits.

Stanley's exploration

In 1876,Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Leo ...

hosted the Brussels Geographic Conference, inviting famous explorers, philanthropists, and members of geographic societies to stir up interest in a "humanitarian" endeavour for Europeans in central Africa to "improve" and " civilize" the lives of the indigenous peoples. At the conference, Leopold organized the International African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

with the cooperation of European and American explorers and the support of several European governments, and was himself elected chairman. Leopold used the association to promote plans to seize independent central Africa under this philanthropic guise.

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

, famous for making contact with British missionary David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

in Africa in 1871, explored the region in 1876–1877, a journey that was described in Stanley's 1878 book ''Through the Dark Continent''. Failing to enlist British interest in the Congo region, Stanley took up service with Leopold II, who hired him to help gain a foothold in the region and annex the region for himself.

From August 1879 to June 1884 Stanley was in the Congo basin, where he built a road from the lower Congo up to Stanley Pool and launched steamers on the upper river. While exploring the Congo for Leopold, Stanley set up treaties with the local chiefs and with native leaders. In essence, the documents gave over all rights of their respective pieces of land to Leopold. With Stanley's help, Leopold was able to claim a great area along the Congo River, and military posts were established.

Christian de Bonchamps, a French explorer who served Leopold in Katanga, expressed attitudes towards such treaties shared by many Europeans, saying:

King Leopold's campaign

Leopold began to create a plan to convince other European powers of the legitimacy of his claim to the region, all the while maintaining the guise that his work was for the benefit of the native peoples under the name of a philanthropic "association".

The king launched a publicity campaign in Britain to distract critics, drawing attention to Portugal's record of slavery, and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same

Leopold began to create a plan to convince other European powers of the legitimacy of his claim to the region, all the while maintaining the guise that his work was for the benefit of the native peoples under the name of a philanthropic "association".

The king launched a publicity campaign in Britain to distract critics, drawing attention to Portugal's record of slavery, and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same most favoured nation

In international economic relations and international politics, most favoured nation (MFN) is a status or level of treatment accorded by one state to another in international trade. The term means the country which is the recipient of this treatme ...

(MFN) status Portugal had offered them. At the same time, Leopold promised Bismarck he would not give any one nation special status, and that German traders would be as welcome as any other.

Leopold then offered France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

the support of the association for French ownership of the entire northern bank of the Congo, and sweetened the deal by proposing that, if his personal wealth proved insufficient to hold the entire Congo, as seemed utterly inevitable, that it should revert to France. On 23 April 1884, the International Association's claim on the southern Congo basin was formally recognized by France on condition that the French got the first option to buy the territory if the Association decided to sell. This may also have helped Leopold to gain recognition for his claim by the other major powers, who thus wanted him to succeed instead of selling his claims to France.

He also enlisted the aid of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, sending President Chester A. Arthur carefully edited copies of the cloth-and-trinket treaties that Stanley (a Welsh-American) claimed to have negotiated with various local authorities, and proposing that, as an entirely disinterested humanitarian body, the Association would administer the Congo for the good of all, handing over power to the natives as soon as they were ready for that responsibility.

Leopold wanted to have the United States support his plans for the Congo in order to gain support from the European nations. He had help from American businessman Henry Shelton Sanford, who had recruited Stanley for Leopold. Henry Sanford swayed President Arthur by inviting him to stay as his guest at Sanford House hotel on Lake Monroe while he was in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

. On 29 November 1883, during his meeting with the President, as Leopold's envoy, he convinced the President that Leopold's agenda was similar to the United States' involvement in Liberia. This satisfied Southern politicians and businessmen, especially Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

Senator John Tyler Morgan. Morgan saw Congo as the same opportunity to send freedmen to Africa so they could contribute to and build the cotton market. Sanford also convinced the people in New York that they were going to abolish slavery and aid travellers and scientists in order to have the public's support. After Henry's actions in convincing President Arthur, the United States was the first country to recognize Congo as a legitimate sovereign state. The United States further participated in the process of recognition by sending the ''US Navy Congo River Expedition of 1885'', which gave a detailed description of travel along the river.

Lobbying and claiming the region

Leopold was able to attract scientific and humanitarian backing for theInternational African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

(, or AIA), which he formed during a Brussels Geographic Conference of geographic societies, explorers, and dignitaries he hosted in 1876. At the conference, Leopold proposed establishing an international benevolent committee for the propagation of civilization among the peoples of central Africa (the Congo region). The AIA was originally conceived as a multi-national, scientific, and humanitarian assembly, and even invited Gustave Moynier as member of the International Law Institute and president of the International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of rules of war and ...

to attend their 1877 conference. The International Law Institute was supportive of the project under the belief that it was aimed to abolish the Congo Basin slave trade. Nevertheless, the AIA eventually became a development company controlled by Leopold.

After 1879 and the crumbling of the International African Association, Leopold's work was done under the auspices of the "Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo" (). The committee, supposedly an international commercial, scientific, and humanitarian group, was in fact made of a group of businessmen who had shares in the Congo, with Leopold holding a large block by proxy. The committee itself eventually disintegrated (but Leopold continued to refer to it and use the defunct organization as a smokescreen for his operations in laying claim to the Congo region).

Determined to look for a colony for himself and inspired by recent reports from central Africa, Leopold began patronizing a number of leading explorers, including Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

. Leopold established the International African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

, a charitable organization to oversee the exploration and surveying of a territory based around the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

, with the stated goal of bringing humanitarian assistance and civilization to the natives. In the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

of 1884–85, European leaders officially noted Leopold's control over the of the notionally independent Congo Free State.

To give his African operations a name that could serve for a political entity, Leopold created, between 1879 and 1882, the International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Congo. It replaced the Belgian Committee for S ...

(, or AIC) as a new umbrella organization. This organization sought to combine the numerous small territories acquired into one sovereign state and asked for recognition from the European powers. On 22 April 1884, thanks to the successful lobbying of businessman Henry Shelton Sanford at Leopold's request, President Chester A. Arthur of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

decided that the cessions claimed by Leopold from the local leaders were lawful and recognized the International Association of the Congo's claim on the region, becoming the first country to do so. In 1884, the US Secretary of State said, "The Government of the United States announces its sympathy with and approval of the humane and benevolent purposes of the International Association of the Congo."

Berlin Conference

In November 1884,

In November 1884, Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

convened a 14-nation conference to submit the Congo question to international control and to finalize the colonial partitioning of the African continent. Most major powers (including Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

) attended the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

, and drafted an international code governing the way that European countries should behave as they acquired African territory. The conference officially recognized the International Congo Association, and specified that it should have no connection with Belgium (beyond a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

), or any other country, but would be under the personal control of King Leopold.

It drew specific boundaries and specified that all nations should have access to do business in the Congo with no tariffs. The slave trade would be suppressed. In 1885, Leopold emerged triumphant. France was given on the north bank (the modern Congo-Brazzaville

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

and Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

), Portugal to the south (modern Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

), and Leopold's personal organization received the balance: , with about 30 million people. However, it still remained for these territories to be occupied under the conference's "Principle of Effective Occupation".

International recognition

Following the United States' recognition of Leopold's colony, other Western powers deliberated on the news. Portugal flirted with the French at first, but the British offered to support Portugal's claim to the entire Congo in return for a free trade agreement and to spite their French rivals. Britain was uneasy at French expansion and had a technical claim on the Congo via Lieutenant Cameron's 1873 expedition fromZanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

to bring home Livingstone's body, but was reluctant to take on yet another expensive, unproductive colony. Bismarck of Germany had vast new holdings in southwest Africa, and had no plans for the Congo, but was happy to see rivals Britain and France excluded from the colony.

In 1885, Leopold's efforts to establish Belgian influence in the Congo Basin were awarded with the ''État Indépendant du Congo'' (CFS, Congo Free State). By a resolution passed in the Belgian Parliament, Leopold became ''roi souverain'', sovereign king, of the newly formed CFS, over which he enjoyed nearly absolute control. The CFS (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo), a country of over two million square kilometres, became Leopold's personal property, the ''Domaine Privé''. Eventually, the Congo Free State was recognized as a neutral independent sovereignty''New International Encyclopedia''. by various European and North American states.

Government

Leopold used the title 'Sovereign of the Congo Free State' as ruler of the Congo Free State. He appointed the heads of the three departments of state: interior, foreign affairs and finances. Each was headed by an administrator-general (''administrateur-général''), later a secretary-general (''secrétaire-général''), who was obligated to enact the policies of the sovereign or else resign. Below the secretaries-general were a series of bureaucrats of decreasing rank: directors general (''directeurs généraux''), directors (''directeurs''), ''chefs de divisions'' (division chiefs) and ''chefs de bureaux'' (bureau chiefs). The departments were headquartered inBrussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

.

Finance was in charge of accounting for income and expenditure and tracking the public debt. Besides diplomacy, foreign affairs was in charge of shipping, education, religion and commerce. The department of the interior was responsible for defence, police, public health and public works. It was also charged with overseeing the exploitation of the Congo's natural resources and plantations. In 1904, the secretary-general of the interior set up a propaganda office, the ''Bureau central de la presse'' ("Central Press Bureau"), in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

under the auspices of the ''Comité pour la représentation des intérêts coloniaux en Afrique'' (in German, ''Komitee zur Wahrung der kolonialen Interessen in Afrika'', "Committee for the Representation of Colonial Interests in Africa").

The oversight of all the departments was nominally in the hands of the Governor-General (''Gouverneur général''), but this office was at times more honorary than real. When the governor-general was in Belgium he was represented in the Congo by a vice governor-general (''vice-gouverneur général''), who was nominally equal in rank to a secretary-general but in fact was beneath them in power and influence. A ''Comité consultatif'' (consultative committee) made up of civil servants was set up in 1887 to assist the governor-general, but he was not obliged to consult it. The vice governor-general on the ground had a state secretary through whom he communicated with his district officers.

The Free State had an independent judiciary headed by a minister of justice at Boma. The minister was equal in rank to the vice governor-general and initially answered to the governor-general, but was eventually made responsible to the sovereign alone. There was a supreme court composed of three judges, which heard appeals, and below it a high court of one judge. These sat at Boma. In addition to these, there were district courts and public prosecutors (''procureurs d'état''). Justice, however, was slow and the system ill-suited to a frontier society.

Leopold's rule

Leopold no longer needed the façade of the ''association'', and replaced it with an appointed cabinet of Belgians who would do his bidding. To the temporary new capital of Boma, he sent a governor-general and a chief of police. The vast

Leopold no longer needed the façade of the ''association'', and replaced it with an appointed cabinet of Belgians who would do his bidding. To the temporary new capital of Boma, he sent a governor-general and a chief of police. The vast Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

was split up into 14 administrative districts

Administrative divisions (also administrative units, administrative regions, subnational entities, or constituent states, as well as many similar generic terms) are geographical areas into which a particular independent sovereign state is divi ...

, each district into zones, each zone into sectors, and each sector into posts. From the district commissioners down to post level, every appointed head was European. However, with little financial means the Free State mainly relied on local elites to rule and tax the vast and hard-to-reach Congolese interior.

In the Free State, Leopold exercised total personal control without much delegation to subordinates. African chiefs played an important role in the administration by implementing government orders within their communities. Throughout much of its existence, however, Free State presence in the territory that it claimed was patchy, with its few officials concentrated in a number of small and widely dispersed "stations" which controlled only small amounts of hinterland. In 1900, there were just 3,000 Europeans in the Congo, of whom only half were Belgian. The colony was perpetually short of administrative staff and officials, who numbered between 700 and 1,500 during the period.

Leopold pledged to suppress the east African slave trade; promote humanitarian policies; guarantee free trade within the colony; impose no import duties for twenty years; and encourage philanthropic and scientific enterprises. Beginning in the mid-1880s, Leopold first decreed that the state asserted rights of proprietorship over all vacant lands throughout the Congo territory. In three successive decrees, Leopold promised the rights of the Congolese in their land to native villages and farms, essentially making nearly all of the CFS ''terres domaniales'' (state-owned land). Leopold further decreed that merchants should limit their commercial operations in rubber trade with the natives. Additionally, the colonial administration liberated thousands of slaves.

Four main problems presented themselves over the next few years.

# Leopold II ran up huge debts to finance his colonial endeavour and risked losing his colony to Belgium.

# Much of the Free State was unmapped jungle, which offered little fiscal and commercial return.

# Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

(part of modern South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

), was expanding his British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

's charter lands from the south and threatened to occupy Katanga (southern Congo) by exploiting the "Principle of Effectivity" loophole in the Berlin Treaty. In this he was supported by Harry Johnston

Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927) was a British explorer, botanist, artist, colonial administrator, and linguist who travelled widely across Africa to speak some of the languages spoken by people on that continent. ...

, the British Commissioner for Central Africa, who was London's representative in the region.

# The Congolese interior was ruled by Arab Zanzibari slavers and sultans, powerful kings and warlords who had to be coerced or defeated by use of force. For example, the slaving gangs of Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

trader Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (– June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī (), was an Afro-Omani ivory and slave owner and trader, explorer, governor and plantation owner. He ...

had a strong presence in the eastern part of the territory in the modern-day Maniema

Maniema Province (''Jimbo la Maniema'', in Swahili) is one of 26 provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Its capital is Kindu. The 2020 population was estimated to be 2,856,300.

Toponymy

Henry Morton Stanley explored the area ...

, Tanganyika and Ituri

Ituri Province ( in Swahili language, Swahili) is one of the 21 provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo created in the Subdivisions of the DR Congo#New provinces, 2015 repartitioning. Ituri, Bas-Uele, Haut-Uele, and Tshopo provinces ...

regions. They were linked to the Swahili coast

The Swahili coast () is a coastal area of East Africa, bordered by the Indian Ocean and inhabited by the Swahili people. It includes Sofala (located in Mozambique); Mombasa, Gede, Kenya, Gede, Pate Island, Lamu, and Malindi (in Kenya); and Dar es ...

via Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

and Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

and had established independent slave states.

Early economy and concessions

Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State. Desperately, he set in motion a system to maximize revenue. The first change was the introduction of the concept of ''terres vacantes'', "vacant" land, which was any land that did not contain a habitation or a cultivated garden plot. All of this land (i.e., most of the country) was therefore deemed to belong to the state. Servants of the state (namely any men in Leopold's employ) were encouraged to exploit it.

Shortly after the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference (1889–1890), Leopold issued a new decree mandating that Africans in a large part of the Free State could sell their harvested products (mostly ivory and rubber) only to the state. This law extended an earlier decree declaring that all "unoccupied" land belonged to the state. Any ivory or rubber collected from the state-owned land, the reasoning went, must belong to the state, thus creating a de facto state-controlled monopoly. Therefore, a large share of the local population could sell only to the state, which could set prices and thereby control the income the Congolese could receive for their work. For local elites, however, this system presented new opportunities, as the Free State and concession companies paid them with guns to tax their subjects in kind.

Trading companies began to lose out to the Free State government, which not only paid no taxes but also collected all the potential income. These companies were outraged by the restrictions on free trade, which the Berlin Act had so carefully protected years before. Their protests against the violation of free trade prompted Leopold to take another, less obvious tack to make money.

Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State. Desperately, he set in motion a system to maximize revenue. The first change was the introduction of the concept of ''terres vacantes'', "vacant" land, which was any land that did not contain a habitation or a cultivated garden plot. All of this land (i.e., most of the country) was therefore deemed to belong to the state. Servants of the state (namely any men in Leopold's employ) were encouraged to exploit it.

Shortly after the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference (1889–1890), Leopold issued a new decree mandating that Africans in a large part of the Free State could sell their harvested products (mostly ivory and rubber) only to the state. This law extended an earlier decree declaring that all "unoccupied" land belonged to the state. Any ivory or rubber collected from the state-owned land, the reasoning went, must belong to the state, thus creating a de facto state-controlled monopoly. Therefore, a large share of the local population could sell only to the state, which could set prices and thereby control the income the Congolese could receive for their work. For local elites, however, this system presented new opportunities, as the Free State and concession companies paid them with guns to tax their subjects in kind.

Trading companies began to lose out to the Free State government, which not only paid no taxes but also collected all the potential income. These companies were outraged by the restrictions on free trade, which the Berlin Act had so carefully protected years before. Their protests against the violation of free trade prompted Leopold to take another, less obvious tack to make money.

Scramble for Katanga

Early in Leopold's rule, the second problem—the British South Africa Company's expansion into the southern Congo Basin—was addressed. The distant Yeke Kingdom, in Katanga on the upper

Early in Leopold's rule, the second problem—the British South Africa Company's expansion into the southern Congo Basin—was addressed. The distant Yeke Kingdom, in Katanga on the upper Lualaba River

The Lualaba River (, , ) flows entirely within the eastern part of Democratic Republic of the Congo. It provides the greatest streamflow to the Congo River, while the River source, source of the Congo is recognized as the Chambeshi River, Chambeshi ...

, had signed no treaties, was known to be rich in copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and thought to have much gold from its slave-trading activities. Its powerful ''mwami'' (King), Msiri

Msiri (c. 1830 – December 20, 1891) founded and ruled the Yeke Kingdom (also called the Garanganze or Garenganze kingdom) in south-east Katanga (now in DR Congo) from about 1856 to 1891. His name is sometimes spelled 'M'Siri' in articles in F ...

, had already rejected a treaty brought by Alfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe (19 May 1853 – 10 December 1935) was Commissioner and Consul-General for the British Central Africa Protectorate and first Governor of Nyasaland.

He trained as a solicitor but was in turn a planter and a professional hu ...

on behalf of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

. In 1891 a Free State expedition extracted a letter from Msiri agreeing to their agents coming to Katanga and later that year Leopold II sent the well-armed Stairs Expedition, led by the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

mercenary William Grant Stairs, to take possession of Katanga one way or another.Moloney (1893): Chapter X–XI.

Msiri tried to play the Free State off against Rhodes and when negotiations bogged down, Stairs flew the Free State flag anyway and gave Msiri an ultimatum. Instead, Msiri decamped to another stockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls, made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened as a defensive wall.

Etymology

''Stockade'' is derived from the French word ''estocade''. The French word was derived f ...

. Stairs sent a force to capture him but Msiri stood his ground, whereupon Captain Omer Bodson

Omer Bodson (5 January 1856 – 20 December 1891) was the Belgian officer who shot and killed Msiri, King of Garanganze ( Katanga) on 20 December 1891 at Bunkeya in what is now the DR Congo. Bodson was then killed by one of Msiri's men.

Milita ...

shot Msiri dead and was fatally wounded in the resulting fight. The expedition cut off Msiri's head and put it on a pole, as he had often done to his enemies. This was to impress upon the locals that Msiri's rule had really ended, after which the successor chief recognized by Stairs signed the treaty.René de Pont-Jest: ''L'Expédition du Katanga, d'après les notes de voyage du marquis Christian de Bonchamps''published 1892 in: Edouard Charton (editor): ''Le Tour du Monde'' magazine, website accessed 5 May 2007.

War with Arab slavers

In the short term, the third problem, that of the African and Arab slavers likeZanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

i/ Swahili strongman Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (– June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī (), was an Afro-Omani ivory and slave owner and trader, explorer, governor and plantation owner. He ...

(actually Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī, but much better known by his nickname) was temporarily solved.

Initially the authority of the Congo Free State was relatively weak in the eastern regions of the Congo. In early 1887, Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

had therefore proposed that Tippu Tip be made governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

(wali) of the Stanley Falls District. Both Leopold II and Barghash bin Said of Zanzibar

Sayyid Barghash bin Said al-Busaidi (1836 – 26 March 1888) (), an Afro-Omani Sultan and the son of Said bin Sultan, was the second Sultan of Zanzibar. He ruled Sultanate of Zanzibar, Zanzibar from 7 October 1870 to 26 March 1888.

Life and rei ...

agreed and on 24 February 1887, Tippu Tip accepted.

In the longer term this alliance was indefensible at home and abroad. Leopold II was heavily criticized by the European public opinion for his dealings with Tippu Tip. In Belgium, the Belgian Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1888, mainly by Catholic intellectuals led by Count Hippolyte d'Ursel, aimed at abolishing the Arab slave trade. Furthermore, Tippu Tip and Leopold were commercial rivals. Every person that Tippu Tip hunted down and put into chattel slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and every pound of ivory he exported to Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

was a loss to Leopold II. This, and Leopold's humanitarian pledges to the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

to end slavery, meant war was inevitable.

Open warfare broke out in late November 1892. Both sides fought by proxy, arming and leading the populations of the upper Congo forests in conflict. By early 1894 the Zanzibari/Swahili slavers were defeated in the eastern Congo region and the Congo Arab war

The Congo Arab war was a colonial war between the Congo Free State and Arab-Swahili warlords associated with the Indian Ocean slave trade in the eastern regions of the Congo Basin between 1892 and 1894.

The war was caused by the Free State and ...

came to an end.

The Belgians freed thousands of men, women and children slaves from Swaihili Arab slave owners and slave traders in Eastern Congo in 1886-1892, enlisted them in the militia ''Force Publique'' or turned them over as prisoners to allied local chiefs, who in turn gave them as laborers for the Belgian conscript workers; when Belgian Congo was established, chattel slavery was legally abolished in 1910, but prisoners were nevertheless conscripted as force laborers for both public and private work projects.

The Lado Enclave

In 1894, King Leopold II signed a treaty with the United Kingdom which conceded a strip of land on the Free State's eastern border in exchange for the

In 1894, King Leopold II signed a treaty with the United Kingdom which conceded a strip of land on the Free State's eastern border in exchange for the Lado Enclave

The Lado Enclave (; ) was a leased territory administered by the Congo Free State and later by the Belgian Congo that existed from 1894 until 1910. Situated on the west bank of the Upper Nile in what is now South Sudan and northwest Uganda, it wa ...

, which provided access to the navigable Nile and extended the Free State's sphere of influence northward into Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

. After rubber profits soared in 1895, Leopold ordered the organization of an expedition into the Lado Enclave, which had been overrun by Mahdist rebels since the outbreak of the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War (; 1881–1899) was fought between the Mahdist Sudanese, led by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided One"), and the forces of the Khedivate of Egypt, initially, and later th ...

in 1881. The expedition was composed of two columns: the first, under Belgian war hero Baron Dhanis, consisted of a sizeable force, numbering around three-thousand, and was to strike north through the jungle and attack the rebels at their base at Rejaf. The second, a much smaller force of only eight-hundred, was led by Louis-Napoléon Chaltin and took the main road towards Rejaf. Both expeditions set out in December 1896.

Although Leopold II had initially planned for the expedition to carry on much farther than the Lado Enclave, hoping indeed to take Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok (), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the Fashoda County of Upper Nile (state), Upper Nile State, in the Greater Upper Nile region of South Sudan. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk people, Shilluk country, formally known as the ...

and then Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

, Dhanis' column mutinied in February 1897, resulting in the death of several Belgian officers and the loss of his entire force. Nonetheless, Chaltin continued his advance, and on 17 February 1897, his outnumbered forces defeated the rebels in the Battle of Rejaf, securing the Lado Enclave as a Belgian territory until Leopold's death in 1909. Leopold's conquest of the Lado Enclave met with approval from the British government, at least initially, which welcomed any aid in their ongoing war with Mahdist Sudan. But frequent raids outside of Lado territory by Belgian Congolese forces based in Rejaf caused alarm and suspicion among British and French officials wary of Leopold's imperial ambitions. In 1910, following the Belgian annexation of the Congo Free State as the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

in 1908 and the death of the Belgian King in December 1909, British authorities reclaimed the Lado Enclave as per the Anglo-Congolese treaty signed in 1894, and added the territory to Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

.

Economy during Leopold's rule

While the war against African powers was ending, the quest for income was increasing, fuelled by the aire policy. By 1890, Leopold was facing considerable financial difficulty. District officials' salaries were reduced to a bare minimum, and made up with a commission payment based on the profit that their area returned to Leopold. After widespread criticism, this "primes system" was substituted for the ''allocation de retraite'' in which a large part of the payment was granted, at the end of the service, only to those territorial agents and magistrates whose conduct was judged "satisfactory" by their superiors. This meant in practice that nothing changed. Congolese communities in the ''Domaine Privé'' were not merely forbidden by law to sell items to anyone but the state; they were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

In direct violation of his promises of free trade within the CFS under the terms of the Berlin Treaty, not only had the state become a commercial entity directly or indirectly trading within its dominion, but also, Leopold had been slowly monopolizing a considerable amount of the ivory and rubber trade by imposing export duties on the resources traded by other merchants within the CFS. In terms of infrastructure, Leopold's regime began construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). The railway, now known as the

While the war against African powers was ending, the quest for income was increasing, fuelled by the aire policy. By 1890, Leopold was facing considerable financial difficulty. District officials' salaries were reduced to a bare minimum, and made up with a commission payment based on the profit that their area returned to Leopold. After widespread criticism, this "primes system" was substituted for the ''allocation de retraite'' in which a large part of the payment was granted, at the end of the service, only to those territorial agents and magistrates whose conduct was judged "satisfactory" by their superiors. This meant in practice that nothing changed. Congolese communities in the ''Domaine Privé'' were not merely forbidden by law to sell items to anyone but the state; they were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

In direct violation of his promises of free trade within the CFS under the terms of the Berlin Treaty, not only had the state become a commercial entity directly or indirectly trading within its dominion, but also, Leopold had been slowly monopolizing a considerable amount of the ivory and rubber trade by imposing export duties on the resources traded by other merchants within the CFS. In terms of infrastructure, Leopold's regime began construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). The railway, now known as the Matadi–Kinshasa Railway

The Matadi–Kinshasa Railway ( French: ''Chemin de fer Matadi-Kinshasa'') is a railway line in Kongo Central province between Kinshasa, the capital of Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the port of Matadi.

The Matadi–Kinshasa Railway was bu ...

, was completed in 1898.

By the final decade of the 19th century, John Boyd Dunlop

John Boyd Dunlop (5 February 1840 – 23 October 1921) was a Scottish people, Scottish inventor and veterinary surgeon who spent most of his career in Ireland. Familiar with making Natural rubber, rubber devices, he invented the first practica ...

's 1887 invention of inflatable, rubber bicycle tubes and the growing usage of the automobile dramatically increased global demand for rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

. To monopolize the resources of the entire Congo Free State, Leopold issued three decrees in 1891 and 1892 that reduced the native population to serfs. Collectively, these forced the natives to deliver all ivory and rubber, harvested or found, to state officers thus nearly completing Leopold's monopoly of the ivory and rubber trade. The rubber came from wild vines in the jungle, unlike the rubber from Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

(''Hevea brasiliensis

''Hevea brasiliensis'', the Pará rubber tree, ''sharinga'' tree, seringueira, or most commonly, rubber tree or rubber plant, is a flowering plant belonging to the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, originally native to the Amazon basin, but is now p ...

''), which was tapped from trees. To extract the rubber, instead of tapping the vines, the Congolese workers would slash them and lather their bodies with the rubber latex. When the latex hardened, it would be scraped off the skin in a painful manner, as it took off the worker's hair with it.

The ''

The ''Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; ) was the military of the Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo from 1885 to 1960. It was established after Belgian Army officers travelled to the Free State to found an armed force in the colony on L ...

'' (FP), Leopold's private army, was used to enforce the rubber quotas. Early on, the FP was used primarily to campaign against the Arab slave trade in the Upper Congo, protect Leopold's economic interests, and suppress the frequent uprisings within the state. The Force Publique's officer corps included only white Europeans (Belgian regular soldiers and mercenaries from other countries). On arriving in the Congo, the army included men from Zanzibar, West Africa, and eventually from the Congo itself. In addition, Leopold had been actually encouraging the slave trade among Arabs in the Upper Congo in return for slaves to fill the ranks of the FP. During the 1890s, the FP's primary role was to exploit the natives as corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state (polity), state for the ...

labourers to promote the rubber trade.

Many of the black soldiers were from far-off peoples of the Upper Congo, while others had been kidnapped in raids on villages in their childhood and brought to Roman Catholic missions, where they received a military training in conditions close to slavery. Armed with modern weapons and the '' chicotte''—a bull whip made of hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

hide—the ''Force Publique'' routinely took and tortured hostages, slaughtered families of rebels, and flogged and raped Congolese people with a reign of terror and abuse that cost millions of lives. One refugee from these horrors described the process:

We were always in the forest to find the rubber vines, to go without food, and our women had to give up cultivating the fields and gardens. Then we starved ... When we failed and our rubber was short, the soldiers came to our towns and killed us. Many were shot, some had their ears cut off; others were tied up with ropes round their necks and taken away.They also burned recalcitrant villages, and above all, cut off the hands of Congolese natives, including children. The human hands were collected as trophies on the orders of their officers to show that bullets had not been wasted. Officers were concerned that their subordinates might waste their ammunition on hunting animals for sport, so they required soldiers to submit one hand for every bullet spent.Cawthorne, Nigel. ''The World's Worst Atrocities'', 1999. Octopus Publishing Group. . These mutilations also served to further terrorize the Congolese into submission. This was all contrary to the promises of uplift made at the Berlin Conference which had recognized the Congo Free State.

Lusambo

Lusambo () is the capital Cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, city of Sankuru province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The town lies north of the confluence of the Sankuru River and the Lubi River. Lusambo is served by Lusambo Airp ...

Humanitarian disaster

Mutilation

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...