Cinchona on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a

Selected Rubiaceae Tribes and Genera. Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden.

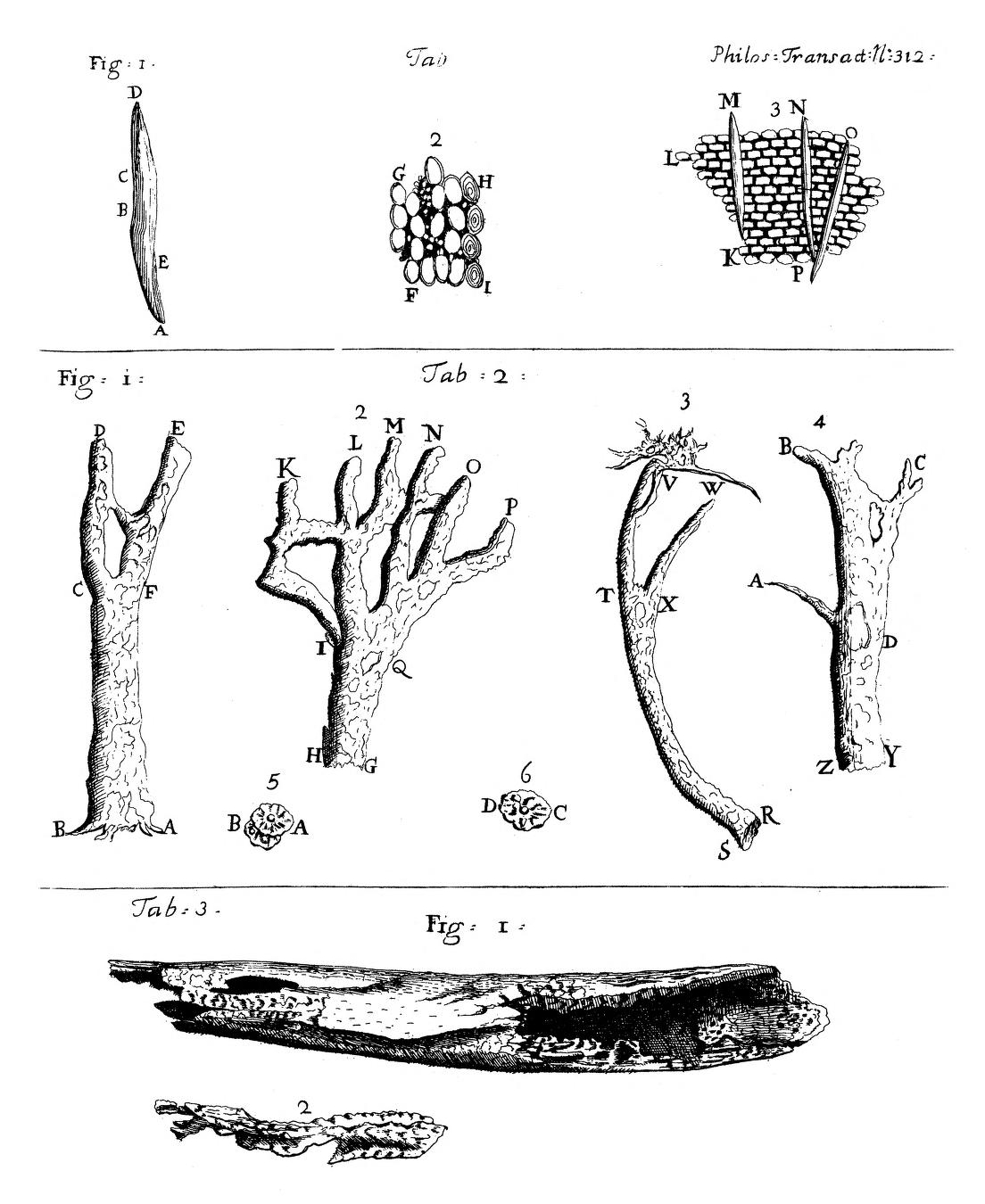

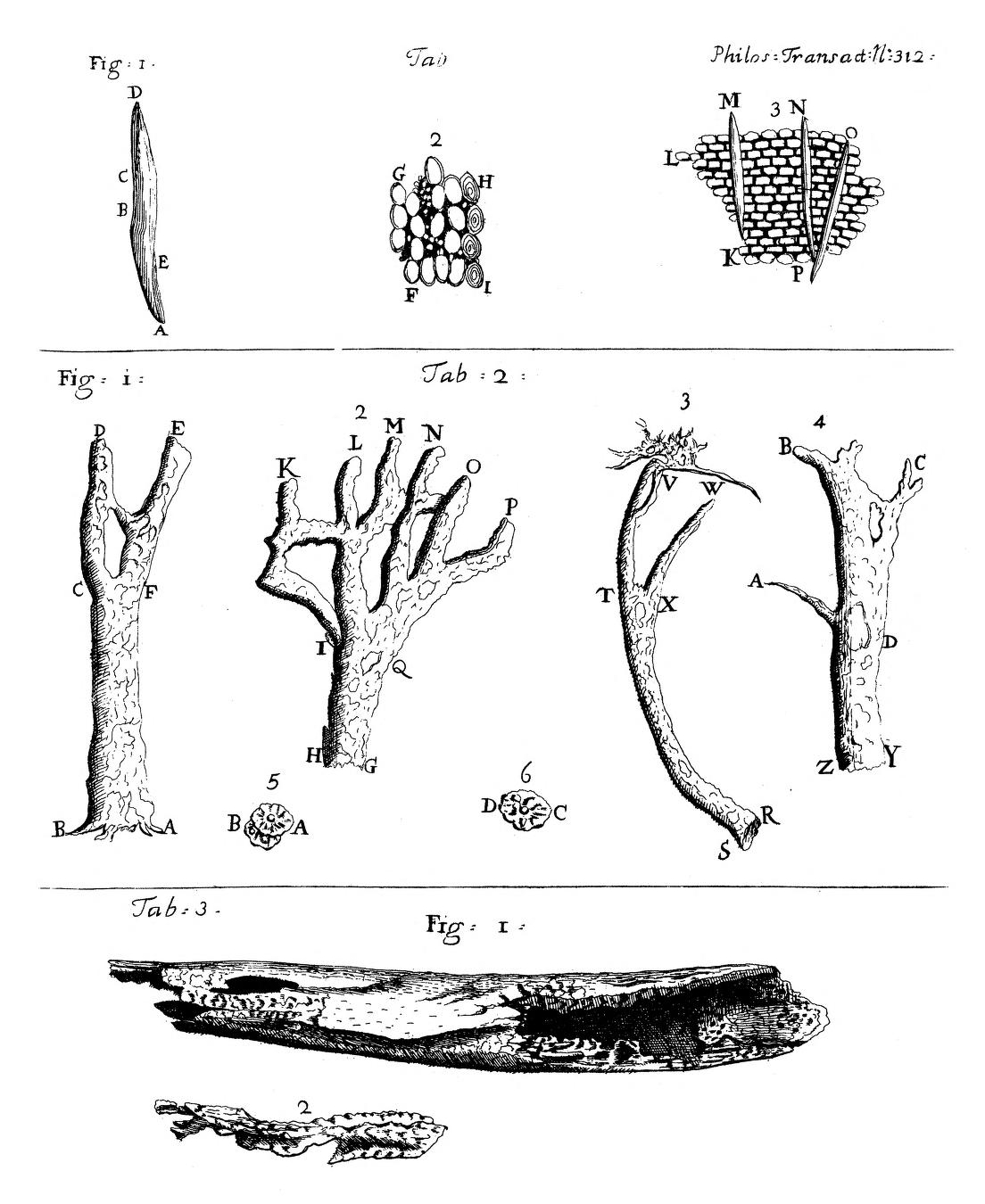

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by astronomer

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by astronomer

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of

online book review

* * * * *

Cinchona Bark

. University of Minnesota Libraries.

Botany Global Issues Map. McGraw Hill.

Cinchona Project Field Books, 1938–1965

from the

"The tree that changed the world map

, By Vittoria Traverso, 28 May 2020, BBC.com. {{Authority control Rubiaceae genera Medicinal plants of South America Quinine Antimalarial agents Tropical flora Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae

Rubiaceae () is a family (biology), family of flowering plants, commonly known as the coffee, madder, or bedstraw family. It consists of terrestrial trees, shrubs, lianas, or herbs that are recognizable by simple, opposite leaves with Petiole ( ...

containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the tropical Andean forests of western South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. A few species are reportedly naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

in Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

, French Polynesia

French Polynesia ( ; ; ) is an overseas collectivity of France and its sole #Governance, overseas country. It comprises 121 geographically dispersed islands and atolls stretching over more than in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. The t ...

, Sulawesi

Sulawesi ( ), also known as Celebes ( ), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the List of islands by area, world's 11th-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Min ...

, Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

in the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

, and São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe, officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, is an island country in the Gulf of Guinea, off the western equatorial coast of Central Africa. It consists of two archipelagos around the two main isla ...

off the coast of tropical Africa, and others have been cultivated in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, where they have formed hybrids.

''Cinchona'' has been historically sought after for its medicinal value, as the bark of several species yields quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and other alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s. These were the only effective treatments against malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

during the height of European colonialism

The phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by various civilizations such as the Phoenicians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Han Chinese, and Ar ...

, which made them of great economic and political importance. Trees in the genus are also known as fever trees because of their antimalarial properties.

The artificial synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

**Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organi ...

of quinine in 1944, an increase in resistant forms of malaria, and the emergence of alternate therapies eventually ended large-scale economic interest in ''Cinchona'' cultivation. ''Cinchona'' alkaloids show promise in treating ''Plasmodium falciparum'' malaria, which has evolved resistance to synthetic drugs. Cinchona plants continue to be revered for their historical legacy; the national tree

This is a list of countries that have officially designated one or more trees as their national trees. Most species in the list are officially designated. Some species hold only an "unofficial" status. Additionally, the list includes trees that we ...

of Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

is in the genus ''Cinchona''.

Etymology and common names

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

named the genus in 1742, based on a claim that the plant had cured the wife of the Count of Chinchón

Count of Chinchón () is a title of Spanish nobility. It was initially created on 9 May 1520 by King Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (Charles I of Spain), who granted the title to Fernando de Cabrera y Bobadilla.

History

The title, and its domi ...

, a Spanish viceroy in Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

, in the 1630s, though the veracity of this story has been disputed. Linnaeus used the Italian spelling ''Cinchona'', but the name Chinchón (pronounced in Spanish) led to Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president fo ...

and others proposing a correction of the spelling to ''Chinchona'', and some prefer the pronunciation for the common name of the plant. Traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) refers to the knowledge, skills, and practices rooted in the cultural beliefs of various societies, especially Indigenous groups, used for maintaining health and treatin ...

uses from South America known as Jesuit's bark and Jesuit's powder have been traced to ''Cinchona''.

Description

''Cinchona'' plants belong to the family Rubiaceae and are largeshrub

A shrub or bush is a small to medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees by their multiple ...

s or small tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, e.g., including only woody plants with secondary growth, only ...

s with evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has Leaf, foliage that remains green and functional throughout the year. This contrasts with deciduous plants, which lose their foliage completely during the winter or dry season. Consisting of many diffe ...

foliage, growing in height. The leaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

are opposite, rounded to lanceolate, and 10–40 cm long. The flower

Flowers, also known as blooms and blossoms, are the reproductive structures of flowering plants ( angiosperms). Typically, they are structured in four circular levels, called whorls, around the end of a stalk. These whorls include: calyx, m ...

s are white, pink, or red, and produced in terminal panicle

In botany, a panicle is a much-branched inflorescence. (softcover ). Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers (and fruit) be pedicellate (having a single stem per flower). The branches of a p ...

s. The fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants (angiosperms) that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which angiosperms disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particular have long propaga ...

is a small capsule containing numerous seed

In botany, a seed is a plant structure containing an embryo and stored nutrients in a protective coat called a ''testa''. More generally, the term "seed" means anything that can be Sowing, sown, which may include seed and husk or tuber. Seeds ...

s. A key character of the genus is that the flowers have marginally hairy corolla lobes. Some species display heterostyly. The tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

Cinchoneae includes the genera ''Cinchonopsis'', ''Jossia'', ''Ladenbergia'', ''Remijia'', ''Stilpnophyllum'', and ''Ciliosemina''. In South America, natural populations of ''Cinchona'' species have geographically distinct distributions. During the 19th century, the introduction of several species into cultivation in the same areas of India and Java, by the English and Dutch East India Company, respectively, led to the formation of hybrids.

Linnaeus described the genus based on the species ''Cinchona officinalis'', which is found only in a small region of Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

and is of little medicinal significance. Nearly 300 species were later described and named in the genus, but a revision of the genus in 1998 identified only 23 distinct species.''Cinchona''.Selected Rubiaceae Tribes and Genera. Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden.

History

Early references

The febrifugal properties of bark from trees now known to be in the genus ''Cinchona'' were used by many South American cultures prior to European contact.Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

played a key role in the transfer of remedies from the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

.

The traditional story connecting ''Cinchona'' species with malaria treatment was first recorded by Italian physician Sebastiano Bado in 1663. It tells of the wife of Luis Jerónimo de Cabrera, 4th Count of Chinchón and Viceroy of Peru, who fell ill in Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

with a tertian fever. A Spanish governor advised a traditional remedy, which resulted in a miraculous and rapid cure. The countess then supposedly ordered a large quantity of the bark and took it back to Europe. Bado claimed to have received this information from an Italian named Antonius Bollus, who was a merchant in Peru. Clements Markham identified the countess as Ana de Osorio, but this was shown to be incorrect by Haggis. Ana de Osorio married the Count of Chinchón in August 1621 and died in 1625, several years before the count was appointed viceroy of Peru in 1628. His second wife, Francisca Henriques de Ribera, accompanied him to Peru. Haggis further examined the count's diaries and found no mention of the countess suffering from fever, although the count himself had many malarial attacks. Because of these and numerous other discrepancies, Bado's story has been generally rejected as little more than a legend.

Quina bark was mentioned by Fray Antonio de La Calancha in 1638 as coming from a tree in Loja (Loxa). He noted that bark powder weighing about two coins was cast into water and drunk to cure fevers and "tertians". Jesuit Father Bernabé Cobo

Bernabé Cobo (born at Lopera in Spain, 1582; died at Lima, Peru, 9 October 1657) was a Spanish Jesuit missionary and writer. He played a part in the early history of quinine by his description of cinchona bark; he brought some to Europe on a vi ...

(1582–1657) also wrote on the "fever tree" in 1653. The legend was popularized in English literature by Markham, and in 1874, he also published a "plea for the correct spelling of the genus ''Chinchona''". Spanish physician and botanist Nicolás Monardes wrote of a New World bark powder used in Spain in 1574, and another physician, Juan Fragoso, wrote of bark powder from an unknown tree in 1600 that was used for treating various ills. Both identify the sources as trees that do not bear fruit and have heart-shaped leaves; they were suggested to have been referring to ''Cinchona'' species.

The name ''quina-quina'' or ''quinquina'' was suggested as an old name for ''Cinchona'' used in Europe and based on the native name used by the Quechua people

Quechua people (, ; ) , Quichua people or Kichwa people may refer to any of the Indigenous peoples of South America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are nativ ...

which means 'bark of barks'. Italian sources spelt ''quina'' as "''cina''", which was a source of confusion with ''Smilax

''Smilax'' is a genus of about 300–350 species, found in the tropics and subtropics worldwide. They are climbing flowering plants, many of which are woody and/or thorny, in the monocotyledon family (biology), family Smilacaceae, native through ...

'' from China. Haggis argued that ''qina'' and Jesuit's bark actually referred to ''Myroxylon peruiferum'', or Peruvian balsam, and that this was an item of importance in Spanish trade in the 1500s. Over time, the bark of ''Myroxylon'' may have been adulterated with the similar-looking bark of what is now known as ''Cinchona''. Gradually, the adulterant became the main product that was the key therapeutic ingredient used in malarial therapy. The bark was included as ''Cortex Peruanus'' in the London Pharmacopoeia in 1677.

Economic significance

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by astronomer

The "fever tree" was finally described carefully by astronomer Charles Marie de la Condamine

Charles Marie de La Condamine (; 28 January 1701 – 4 February 1774) was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador, measuring the length of a degree of latitude at the equator and pre ...

, who visited Quito

Quito (; ), officially San Francisco de Quito, is the capital city, capital and second-largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its metropolitan area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha Province, P ...

in 1735 on a quest to measure an arc of the meridian. The species he described, ''Cinchona officinalis'', however, was found to be of little therapeutic value. The first living plants seen in Europe were ''C. calisaya'' plants grown at the ''Jardin des Plantes'' from seeds collected by Hugh Algernon Weddell from Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

in 1846. José Celestino Mutis

José Celestino Bruno Mutis y Bosio (6 April 1732 – 11 September 1808) was a Spanish people, Spanish priest, botanist and mathematician. He was a significant figure in the Spanish American Enlightenment, whom Alexander von Humboldt met with ...

, physician to the Viceroy of Nueva Granada, Pedro Messia de la Cerda, gathered information on cinchona in Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

from 1760 and wrote a manuscript, ''El Arcano de la Quina'' (1793), with illustrations. He proposed a Spanish expedition to search for plants of commercial value, which was approved in 1783 and was continued after his death in 1808 by his nephew Sinforoso Mutis. As demand for the bark increased, the trees in the forests began to be destroyed. To maintain their monopoly on cinchona bark, Peru and surrounding countries began outlawing the export of cinchona seeds and saplings beginning in the early 19th century.

The colonial European powers eventually considered growing the plant in other parts of the tropics. The French mission of 1743, of which de la Condamine was a member, lost their cinchona plants when a wave took them off their ship. The Dutch sent Justus Hasskarl, who brought plants that were then cultivated in Java from 1854. English explorer Clements Markham went to collect plants that were introduced in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

and the Nilgiris of southern India in 1860. The main species introduced were '' C. succirubra'', or red bark, (now ''C. pubescens'') as its sap turned red on contact with air, and '' Cinchona calisaya''. The alkaloids quinine and cinchonine were extracted by Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou in 1820. Two more key alkaloids, quinidine and cinchonidine, were later identified and it became a routine in quinology to examine the contents of these components in assays. The yields of quinine in the cultivated trees were low and time was needed to develop sustainable methods to extract bark.

In the meantime, Charles Ledger and his native assistant Manuel Incra Mamani collected another species from Bolivia. Mamani was caught and beaten by Bolivian officials, leading to his death, but Ledger obtained seeds containing high levels of quinine. These seeds were offered to the British, who were uninterested, leading to the rest being sold to the Dutch. The Dutch saw their value and multiplied the stock. The species later named '' Cinchona ledgeriana'' yielded 8 to 13% quinine in bark grown in Dutch Indonesia, which effectively outcompeted the British Indian production which focused on a range of alkaloids other than quinine. Only later did the English see the value and sought to obtain the seeds of ''C. ledgeriana'' from the Dutch.

Francesco Torti used the response of fevers to treatment with ''Cinchona'' as a system of classification of fevers or a means for diagnosis between malarial and non-malarial fevers. Its use in the effective treatment of malaria brought an end to treatment by bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) was the deliberate withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and othe ...

and long-held ideas of humorism

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 17th ce ...

from Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

. Clements Markham was knighted for his role in establishing ''Cinchona'' species in Indonesia. Hasskarl was knighted with the Dutch order of the Lion.

Ecology

''Cinchona'' species are used as food plants by thelarva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

e of some lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) or lepidopterans is an order (biology), order of winged insects which includes butterflies and moths. About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera have been described, representing 10% of the total described species of living organ ...

n species, including the engrailed, the commander, and members of the genus ''Endoclita

''Endoclita'' is a genus of moths of the family Hepialidae. There are 60 described species found in eastern and southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

Species

*'' Endoclita aboe'' – India

*'' Endoclita absurdus'' – China

*'' Endoclita ...

'', including '' E. damor'', '' E. purpurescens'', and '' E. sericeus''.

'' C. pubescens'' has grown uncontrolled on some islands, such as the Galapagos, where it has posed the risk of outcompeting native plant species.

Cultivation and use

Whether cinchona bark was used in any traditional medicines within Andean Indigenous groups when it first came to notice by Europeans is unclear. Since its first confirmed medicinal record in the early 17th century, it has been used as a treatment for malaria. This use was popularised in Europe by the Spanish colonisers of South America. The bark containsalkaloids

Alkaloids are a broad class of naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large variety of organisms i ...

, including quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and quinidine

Quinidine is a class I antiarrhythmic agent, class IA antiarrhythmic agent used to treat heart rhythm disturbances. It is a diastereomer of Antimalarial medication, antimalarial agent quinine, originally derived from the bark of the cinchona tre ...

. Cinchona is the only economically practical source of quinine, a drug that is still recommended for the treatment of ''falciparum'' malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

.

Europe

Italian botanist Pietro Castelli wrote a pamphlet noteworthy as being the first Italian publication to mention the ''Cinchona'' species. By the 1630s (or 1640s, depending on the reference), the bark was being exported to Europe. In the late 1640s, the method of use of the bark was noted in the '' Schedula Romana.'' The Royal Society of London published in its first year (1666) "An account of Dr. Sydenham's book, entitled, Methodus curandi febres . . ." English King Charles II called upon Robert Talbor, who had become famous for his miraculous malaria cure. Because at that time the bark was in religious controversy, Talbor gave the king the bitter bark decoction in great secrecy. The treatment gave the king complete relief from the malaria fever. In return, Talbor was offered membership of the prestigiousRoyal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

.

In 1679, Talbor was called by the King of France, Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, whose son was suffering from malarial fever. After a successful treatment, Talbor was rewarded by the king with 3,000 gold crowns and a lifetime pension for this prescription. Talbor was asked to keep the entire episode secret. After Talbor's death, the French king published this formula: seven grams of rose leaves, two ounces of lemon juice and a strong decoction of the cinchona bark served with wine. Wine was used because some alkaloids of the cinchona bark are not soluble in water, but are soluble in the ethanol in wine. In 1681 '' Água de Inglaterra'' was introduced into Portugal from England by Dr. Fernando Mendes who, similarly, "received a handsome gift from ( King Pedro) on condition that he should reveal to him the secret of its composition and withhold it from the public".

In 1738, ''Sur l'arbre du quinquina'', a paper written by Charles Marie de La Condamine

Charles Marie de La Condamine (; 28 January 1701 – 4 February 1774) was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador, measuring the length of a degree of latitude at the equator and pre ...

, lead member of the expedition, along with Pierre Godin and Louis Bouger that was sent to Ecuador to determine the length of a degree of the 1/4 of meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

in the neighbourhood of the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

, was published by the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

. In it he identified three separate species.

Homeopathy

The birth ofhomeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

was based on cinchona bark testing. The founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann ( , ; 10 April 1755 – 2 July 1843) was a German physician, best known for creating the pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine called homeopathy.

Early life

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann w ...

, when translating William Cullen

William Cullen (; 15 April 17105 February 1790) was a British physician, chemist and agriculturalist from Hamilton, Scotland, who also served as a professor at the Edinburgh Medical School. Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enli ...

's ''Materia medica

''Materia medica'' ( lit.: 'medical material/substance') is a Latin term from the history of pharmacy for the body of collected knowledge about the therapeutic properties of any substance used for healing (i.e., medications). The term derives f ...

'', noticed Cullen had written that Peruvian bark was known to cure intermittent fevers. Hahnemann took daily a large, rather than homeopathic, dose of Peruvian bark. After two weeks, he said he felt malaria-like symptoms. This idea of "like cures like" was the starting point of his writings on homeopathy. Hahnemann's symptoms have been suggested by researchers, both homeopaths and skeptics, as being an indicator of his hypersensitivity to quinine.

Widespread cultivation

The bark was very valuable to Europeans in expanding their access to and exploitation of resources in distant colonies and at home. Bark gathering was often environmentally destructive, destroying huge expanses of trees for their bark, with difficult conditions for low wages that did not allow the indigenous bark gatherers to settle debts even upon death. Further exploration of theAmazon Basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributary, tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries ...

and the economy of trade in various species of the bark in the 18th century is captured by Lardner Gibbon:

... this bark was first gathered in quantities in 1849, though known for many years. The best quality is not quite equal to that of Yungas, but only second to it. There are four other classes of inferior bark, for some of which the bank pays fifteen dollars per quintal. The best, by law, is worth fifty-four dollars. The freight to Arica is seventeen dollars the mule load of three quintals. Six thousand quintals of bark have already been gathered from Yuracares. The bank was established in the year 1851. Mr. haddäusHaenke mentioned the existence of cinchona bark on his visit to Yuracares in 1796 :— ''Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon'', by Lieut. Lardner Gibbon, USN. Vol. II, Ch. 6, pp. 146–47.It was estimated that the British Empire incurred direct losses of 52 to 62 million pounds a year due to malaria sickness each year. It was therefore of great importance to secure the supply of the cure. In 1860, a British expedition to South America led by

Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president fo ...

smuggled back cinchona seeds and plants, which were introduced in several areas of British India and Sri Lanka. In India, it was planted in Ootacamund by William Graham McIvor. In Sri Lanka, it was planted in the Hakgala Botanical Garden in January 1861. James Taylor

James Vernon Taylor (born March 12, 1948) is an American singer-songwriter and guitarist. A six-time Grammy Award winner, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000.

Taylor achieved his breakthrough in 1970 with the single "Fi ...

, the pioneer of tea planting in Sri Lanka, was one of the pioneers of cinchona cultivation. By 1883, about were in cultivation in Sri Lanka, with exports reaching a peak of 15 million pounds in 1886. The cultivation (initially of '' C. succirubra'' (now ''C. pubescens'') and later of ''C. calisaya'') was extended through the work of George King George King may refer to:

Politics

* George King (Australian politician) (1814–1894), New South Wales and Queensland politician

* George King, 3rd Earl of Kingston (1771–1839), Irish nobleman and MP for County Roscommon

* George Clift King (184 ...

and others into the hilly terrain of Darjeeling District of Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

. Cinchona factories were established at Naduvattam in the Nilgiris and at Mungpoo, Darjeeling, West Bengal. Quinologists were appointed to oversee the extraction of alkaloids with John Broughton in the Nilgiris and C.H. Wood at Darjeeling. Others in the position included David Hooper and John Eliot Howard.

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in

In 1865, "New Virginia" and "Carlota Colony" were established in Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

by Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and ...

, a former Confederate in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Postwar Confederates were enticed there by Maury, now the "Imperial Commissioner of Immigration" for Emperor Maximillian of Mexico, and Archduke of Habsburg. All that survives of those two colonies are the flourishing groves of ''cinchonas'' established by Maury using seeds purchased from England. These seeds were the first to be introduced into Mexico.

The cultivation of cinchona led from the 1890s to a decline in the price of quinine, but the quality and production of raw bark by the Dutch in Indonesia led them to dominate world markets. The producers of processed drugs in Europe (especially Germany), however, bargained and caused fluctuations in prices, which led to a Dutch-led Cinchona Agreement in 1913 that ensured a fixed price for producers. A '' Kina Bureau'' in Amsterdam regulated this trade.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Japanese conquered Java and the United States lost access to the cinchona plantations that supplied war-critical quinine medication. Botanical expeditions called Cinchona Missions were launched between 1942 and 1944 to explore promising areas of South America in an effort to locate cinchona species that contained quinine and could be harvested for quinine production. As well as being ultimately successful in their primary aim, these expeditions also identified new species of plants and created a new chapter in international relations between the United States and other nations in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

.

Chemistry

Cinchona alkaloids

alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s, the most familiar of which is quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, an antipyretic

An antipyretic (, from ''anti-'' 'against' and ' 'feverish') is a substance that reduces fever. Antipyretics cause the hypothalamus to override a prostaglandin-induced increase in temperature. The body then works to lower the temperature, which r ...

(antifever) agent especially useful in treating malaria. For a while the extraction of a mixture of alkaloids from the cinchona bark, known in India as the cinchona febrifuge, was used. The alkaloid mixture or its sulphated form mixed in alcohol and sold as quinetum was however very bitter and caused nausea, among other side effects.

Cinchona alkaloids include:

* cinchonine

Cinchonine is an alkaloid found in ''Cinchona officinalis''. It is used in asymmetric synthesis in organic chemistry. It is a stereoisomer and pseudo-enantiomer of cinchonidine.

It is structurally similar to quinine, an antimalarial drug.

It i ...

and cinchonidine (stereoisomer

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

s with R1 = vinyl

Vinyl may refer to:

Chemistry

* Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a particular vinyl polymer

* Vinyl cation, a type of carbocation

* Vinyl group, a broad class of organic molecules in chemistry

* Vinyl polymer, a group of polymers derived from vinyl ...

, R2 = hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

)

* quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

and quinidine

Quinidine is a class I antiarrhythmic agent, class IA antiarrhythmic agent used to treat heart rhythm disturbances. It is a diastereomer of Antimalarial medication, antimalarial agent quinine, originally derived from the bark of the cinchona tre ...

(stereoisomer

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

s with R1 = vinyl, R2 = methoxy

In organic chemistry, a methoxy group is the functional group consisting of a methyl group bound to oxygen. This alkoxy group has the formula .

On a benzene ring, the Hammett equation classifies a methoxy substituent at the ''para'' position a ...

)

* dihydroquinine and dihydroquinidine (stereoisomers with R1 = ethyl, R2 = methoxy)

They find use in organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

as organocatalyst

In organic chemistry, organocatalysis is a form of catalysis in which the rate of a chemical reaction is increased by an Organic compound, organic catalyst. This "organocatalyst" consists of carbon, hydrogen, sulfur and other nonmetal elements fo ...

s in asymmetric synthesis.

Other chemicals

Alongside the alkaloids, many cinchona barks contain cinchotannic acid, a particulartannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and Precipitation (chemistry), precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. The term ''tannin'' is widel ...

, which by oxidation rapidly yields a dark-coloured phlobaphene called red cinchonic, cinchono-fulvic acid, or cinchona red.

In 1934, efforts to make malaria drugs cheap and effective for use across countries led to the development of a standard called "totaquina" proposed by the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. Totaquina required a minimum of 70% crystallizable alkaloids, of which at least 15% was to be quinine with not more than 20% amorphous alkaloids.

Species

There are at least 24 species of ''Cinchona'' recognized by botanists. There are likely several unnamed species and many intermediate forms that have arisen due to the plants' tendency to hybridize. * '' Cinchona anderssonii'' Maldonado * '' Cinchona antioquiae'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona asperifolia'' Wedd. * '' Cinchona barbacoensis'' H.Karst. * '' Cinchona calisaya'' Wedd. * '' Cinchona capuli'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona fruticosa'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona glandulifera'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona hirsuta'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona krauseana'' L.Andersson * '' Cinchona lancifolia'' Mutis * '' Cinchona lucumifolia'' Pav. ex Lindl. * '' Cinchona macrocalyx'' Pav. ex DC. * '' Cinchona micrantha'' Ruiz & Pav. * '' Cinchona mutisii'' Lamb. * '' Cinchona nitida'' Ruiz & Pav. * ''Cinchona officinalis

''Cinchona officinalis'' is a South American tree in the family Rubiaceae. It is native to wet montane forests in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, between 1600–2700 meters above sea level.

Description

''Cinchona officinalis'' is a shrub ...

'' L.

* '' Cinchona parabolica'' Pav. in J.E.Howard

* '' Cinchona pitayensis'' (Wedd.) Wedd.

* '' Cinchona pubescens'' Vahl

* '' Cinchona pyrifolia'' L.Andersson

* '' Cinchona rugosa'' Pav. in J.E.Howard

* '' Cinchona scrobiculata'' Humb. & Bonpl.

* '' Cinchona villosa'' Pav. ex Lindl.

See also

* Cinchonism *History of malaria

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent e ...

* ''Quillaja saponaria

''Quillaja saponaria'', the soap bark tree or soapbark, is an evergreen tree in the family Quillajaceae, native to warm temperate central Chile. In Chile it occurs from 32nd parallel south, 32 to 40th parallel south, 40° South Latitude approxim ...

''

Notes

References

* Gänger, Stefanie. ''A Singular Remedy: Cinchona across the Atlantic World, 1751–1820'' (Cambridge University Press, 2021online book review

* * * * *

External links

* Burba, JCinchona Bark

. University of Minnesota Libraries.

Botany Global Issues Map. McGraw Hill.

Cinchona Project Field Books, 1938–1965

from the

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institution ...

Articles

"The tree that changed the world map

, By Vittoria Traverso, 28 May 2020, BBC.com. {{Authority control Rubiaceae genera Medicinal plants of South America Quinine Antimalarial agents Tropical flora Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus