From 1910 to 1945,

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

was ruled by the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

under the name Chōsen (), the Japanese reading of "

Joseon

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

".

Japan first took Korea into its sphere of influence during the late 1800s. Both Korea (

Joseon

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

) and Japan had been under policies of

isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

, with Joseon being a

tributary state of Qing China. However, in 1854,

Japan was forcibly opened by the United States. It then rapidly modernized under the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

, while Joseon continued to resist foreign attempts to open it up. Japan eventually succeeded in opening Joseon with the unequal

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 (also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty of Amity in Japan and the Treaty of Ganghwa Island in Korea) was made between representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Joseon, Kingdom of Joseon in 1876.Chung, Young ...

.

Afterwards, Japan embarked on a decades-long process of defeating its local rivals, securing alliances with Western powers, and asserting its influence in Korea. Japan

assassinated the defiant Korean queen and intervened in the

Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution () was a peasant revolt that took place between 11 January 1894 and 25 December 1895 in Korea. The peasants were primarily followers of Donghak, a Neo-Confucian movement that rejected Western technology and i ...

.

[Donald Keene, ''Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his World, 1852–1912'' (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002)]

p. 517.

After Japan defeated China in the 1894–1895

First Sino–Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as the Jiawu ...

, Joseon became nominally independent and declared the short-lived

Korean Empire

The Korean Empire, officially the Empire of Korea or Imperial Korea, was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by King Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire lasted until the Japanese annexation of Korea in August 1910.

Dur ...

. Japan then defeated Russia in the 1904–1905

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, making it the sole regional power. It then moved quickly to fully absorb Korea. It first made Korea a

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

with the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905, also known as the Eulsa Treaty, was made between delegates of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire in 1905. Negotiations were concluded on November 17, 1905. The treaty deprived Korea of its diplomatic s ...

, and then

ruled the country indirectly through the

Japanese resident-general of Korea

The Japanese resident-general of Korea (; ) was a post overseeing the Japanese protectorate of Korea from 1905 to 1910.

List of Japanese residents-general

See also

* Governor-General of Korea

* Governor-General of Taiwan

The governo ...

. After forcing Emperor

Gojong to abdicate in 1907, Japan then formally colonized Korea with the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, also known as the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty, was made by representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire on 22 August 1910. In this treaty, Japan formally annexed Korea following the J ...

. The territory was then administered by the

governor-general of Chōsen

The Governor-General of Chōsen (; ) was the chief administrator of the : a part of an administrative organ established by the Imperial government of Japan. The position existed from 1910 to 1945.

The governor-general of Chōsen was established ...

, based in

Keijō

, or Gyeongseong (), was an administrative district of Korea under Japanese rule that corresponds to the present Seoul, the capital of South Korea.

History

When the Empire of Japan annexed the Korean Empire, it made Seoul the colonial capita ...

(

Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

), until the end of the colonial period.

Japan made sweeping changes in Korea. Under the pretext of the racial theory known as ''

Nissen dōsoron

''Nissen dōsoron'' (; ) is a theory that reinforces the idea that the Japanese people and the Koreans, Korean people share a common ancestry. It was first introduced during the Japanese annexation of Korea in the early 20th century by Japanese hi ...

'', it began a process of

Japanization

Japanization or Japanisation is the process by which Japanese culture dominates, assimilates, or influences other cultures. According to ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', "To japanize" means "To make or become Jap ...

, eventually

functionally banning the use of Korean names and the Korean language altogether. Tens of thousands of cultural artifacts were taken to Japan, and hundreds of historic buildings like the

Gyeongbokgung

Gyeongbokgung () is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. Established in 1395, it was the first royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and is now one of the most significant tourist attractions in the country.

The palace was among the first ...

and

Deoksugung

Deoksugung (), also called Deoksu Palace or Deoksugung Palace, is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. It was the first main palace of the 1897–1910 Korean Empire and is now a major tourist attraction. It has a mix of traditional Korea ...

palaces were either partially or completely demolished. Japan also built infrastructure and industry. Railways, ports, and roads were constructed, although in numerous cases workers were subjected to extremely poor working circumstances and discriminatory pay. While Korea's economy grew under Japan, many argue that many of the infrastructure projects were designed to extract resources from the peninsula, and not to benefit its people.

Most of Korea's infrastructure built during this time was destroyed during the 1950–1953

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

These conditions led to the birth of the

Korean independence movement

The Korean independence movement was a series of diplomatic and militant efforts to liberate Korea from Japanese rule. The movement began around the late 19th or early 20th century, and ended with the surrender of Japan in 1945. As independence a ...

, which acted both politically and

militantly sometimes within the Japanese Empire, but mostly from outside of it. Koreans were also subjected to a number of mass murders, including the

Gando Massacre,

Kantō Massacre

The was a mass murder in the Kantō region of Japan committed in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. With the explicit and implicit approval of parts of the Japanese government, the Japanese military, police, and vigilantes mu ...

,

Jeamni massacre, and

Shinano River incident.

Beginning in 1939 and during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Japan mobilized around 5.4 million Koreans to support its war effort. Many were moved forcefully from their homes, and set to work in generally extremely poor working conditions, although there was a range in what people experienced. Women and girls were controversially forced into sexual slavery as "

comfort women

Comfort women were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term ''comfort women'' is a translation of the Japanese , a euphemism ...

". After the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

at the end of the war, Korea was liberated, although it

was immediately divided under the

rule of the Soviet Union and

of the United States.

The legacy of Japanese colonization was hotly contested even just after its end, and is still extremely controversial. There is a significant range of opinions in both South Korea and Japan, and historical topics regularly cause diplomatic issues. Within South Korea, a particular focus is the role of the numerous ethnic

Korean collaborators with Japan, who have been variously punished or left alone. This controversy is exemplified in the legacy of

Park Chung Hee

Park Chung Hee (; ; November14, 1917October26, 1979) was a South Korean politician and army officer who served as the third president of South Korea from 1962 after he seized power in the May 16 coup of 1961 until Assassination of Park Chung ...

, South Korea's most influential and controversial president, who collaborated with the Japanese military and continued to praise it even after the colonial period. Until 1964, South Korea and Japan had no functional diplomatic relations, until they signed the

Treaty on Basic Relations, which declared "already

null and void" the past unequal treaties, especially those of 1905 and 1910.

Despite this,

relations between Japan and South Korea have oscillated between warmer and colder periods, often due to conflicts over the historiography of this era.

Terminology

During the period of Japanese colonial rule, Korea was officially known as ,

although the former name continued to be used internationally.

In South Korea, the period is usually described as the "Imperial Japanese compulsive occupation period" (). Other terms, although often considered obsolete, include "Japanese Imperial Period" (), "The dark Japanese Imperial Period" (), and "

Wae (Japanese) administration period" ().

In Japan, the term has been used.

Background

Political turmoil in Korea

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876

On 27 February 1876, the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 (also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty of Amity in Japan and the Treaty of Ganghwa Island in Korea) was made between representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Joseon, Kingdom of Joseon in 1876.Chung, Young ...

was signed. It was designed to open up Korea to Japanese trade, and the rights granted to Japan under the treaty were similar to those granted Western powers in Japan following the visit of

Commodore Perry in 1854.

The treaty ended Korea's status as

a protectorate of China, forced opening of three Korean ports to Japanese trade, granted

extraterritorial rights

Extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ) is the legal ability of a government to exercise authority beyond its normal boundaries.

Any authority can claim ETJ over any external territory they wish. However, for the claim to be effective in the external ...

to Japanese citizens, and was an

unequal treaty

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing dynasty, Qing China, Tokugawa shogunate, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon, Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom of Great ...

signed under duress (

gunboat diplomacy

Gunboat diplomacy is the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to the superior force.

The term originated in ...

) of the

Ganghwa Island incident

The Ganghwa Island incident or the Japanese Battle of Ganghwa ( ''Unyo-ho sageon'' meaning "'' Un'yō'' incident"; ''Kōka-tō jiken'') was an armed clash between the Joseon dynasty of Korea and Japan which occurred in the vicinity of Ganghwa ...

of 1875.

[A reckless adventure in Taiwan amid Meiji Restoration turmoil]

''The Asahi Shimbun'', Retrieved on 22 July 2007.

Imo Incident

The regent

Daewongun

Heungseon Daewongun (; 24 January 1821 – 22 February 1898) was the title of Yi Ha-eung, the regent of Joseon during the minority of Emperor Gojong in the 1860s. Until his death, he was a key political figure of late Joseon Korea. He was also ca ...

, who remained opposed to any concessions to Japan or the West, helped organize the Mutiny of 1882, an anti-Japanese outbreak against

Queen Min

Empress Myeongseong (; 17 November 1851 – 8 October 1895) was the official wife of Gojong, the 26th king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Korean Empire. During her lifetime, she was known by the name Queen Min (). After the founding o ...

and her allies.

[Marius B. Jansen (April 1989). ''The Cambridge History of Japan'' Volume 5 The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press .] Motivated by resentment of the preferential treatment given to newly trained troops, the Daewongun's forces, or "old military", killed a Japanese training cadre, and attacked the Japanese

legation

A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a minister. Ambassadors outranked ministers and had precedence at official events. Legation ...

.

Japanese diplomats,

[Japanese Cabinet Meeting document Nov, 1882](_blank)

p. 6 left 陸軍外務両者上申故陸軍工兵中尉堀本禮造外二名並朝鮮国二於テ戦死ノ巡査及公使館雇ノ者等靖国神社ヘ合祀ノ事 policemen,

[Japanese Cabinet Meeting document Nov. 1882](_blank)

p. 2 left students,

and some Min clan members were also killed during the incident. The Daewongun was briefly restored to power, only to be forcibly taken to China by Chinese troops dispatched to Seoul to prevent further disorder.

In August 1882, the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1882

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1882, also known as the Treaty of Chemulpo or the ''Chemulpo Convention,'' was negotiated between Japan and Korea following the Imo Incident in July 1882.Takenobu, Yoshitaro. (1887). ; excerpt, "''Korea agreed in the ...

indemnified the families of the Japanese victims, paid reparations to the Japanese government in the amount of 500,000 yen, and allowed a company of Japanese guards to be stationed at the Japanese legation in Seoul.

Kapsin Coup

The struggle between the Heungseon Daewongun's followers and those of Queen Min was further complicated by competition from a Korean independence faction known as the Progressive Party (''Gaehwa-dang''), as well as the Conservative faction. While the former sought Japan's support, the latter sought China's support.

On 4 December 1884, the Progressive Party, assisted by the Japanese, attempted the

Kapsin Coup

The Kapsin Coup, also known as the Kapsin Revolution, was a failed three-day coup d'état that occurred in Korea during 1884. Korean reformers in the Enlightenment Party sought to initiate rapid changes within the country, including eliminating ...

, in which they attempted to maintain Gojong but replace the government with a pro-Japanese one. They also wished to liberate Korea from Chinese suzerainty.

However, this proved short-lived, as conservative Korean officials requested the help of Chinese forces stationed in Korea.

The coup was put down by Chinese troops, and a Korean mob killed both Japanese officers and Japanese residents in retaliation.

Some leaders of the Progressive Party, including

Kim Okkyun, fled to Japan, while others were executed.

For the next 10 years, Japanese expansion into the Korean economy was approximated only by the efforts of

tsarist Russia, but eventually would be annexed by Japan in 1910 (See Prelude to annexation).

Donghak Revolution and First Sino-Japanese War

The outbreak of the

Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution () was a peasant revolt that took place between 11 January 1894 and 25 December 1895 in Korea. The peasants were primarily followers of Donghak, a Neo-Confucian movement that rejected Western technology and i ...

in 1894 provided a seminal pretext for direct military intervention by Japan in the affairs of Korea. In April 1894, Joseon asked for Chinese assistance in ending the revolt. In response, Japanese leaders, citing a violation of the

Convention of Tientsin

The , also known as the Tianjin Convention, was an agreement signed by the Qing Empire of China and the Empire of Japan in Tientsin, China on 18 April 1885. It was also called the "Li-Itō Convention".

Following the Gapsin Coup in Joseon in 188 ...

as a pretext, decided upon military intervention to challenge China. On 3 May 1894, 1,500 Qing forces appeared in

Incheon

Incheon is a city located in northwestern South Korea, bordering Seoul and Gyeonggi Province to the east. Inhabited since the Neolithic, Incheon was home to just 4,700 people when it became an international port in 1883. As of February 2020, ...

. On 23 July 1894, Japan attacked Seoul in defiance of the Korean government's demand for withdrawal, and then occupied it and started the Sino-Japanese War. Japan won the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

, and China signed the

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China or the in Japan, was signed at the hotel in Shimonoseki, Japan, on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China. It was a treaty that ended the First Sino-Japanese War, ...

in 1895. Among its many stipulations, the treaty recognized "the full and complete independence and autonomy of Korea", thus ending Joseon's

tributary

A tributary, or an ''affluent'', is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream (''main stem'' or ''"parent"''), river, or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries, and the main stem river into which they ...

relationship with Qing, leading to the proclamation of the full independence of Joseon in 1895. At the same time, Japan suppressed the peasant revolt with Korean government forces.

Assassination of Queen Min

The Japanese minister to Korea,

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

, orchestrated a plot against 43-year-old Queen Min (later given the title of "

Empress Myeongseong

Empress Myeongseong (; 17 November 1851 – 8 October 1895) was the official wife of Gojong, the 26th king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Korean Empire. During her lifetime, she was known by the name Queen Min (). After the founding o ...

"), and on 8 October 1895, she was assassinated by Japanese agents.

The Korean military unit,

Hullyŏndae, participated in the assassination. With Korean aid, Japanese assassins were allowed to enter the palace Gyeongbokgung. In 2001, Russian reports on the assassination were found in the archives of the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Federation. The documents included the testimony of King Gojong, several witnesses of the assassination, and

Karl Ivanovich Weber's report to

Aleksey Lobanov-Rostovsky, the Foreign Minister of Russia, by Park Jonghyo. Weber was the ''

chargé d'affaires

A (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador. The term is Frenc ...

'' at the Russian legation in Seoul at that time.

According to a Russian eyewitness, Seredin-Sabatin, an employee of the king, a group of Japanese agents entered

Gyeongbokgung

Gyeongbokgung () is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. Established in 1395, it was the first royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and is now one of the most significant tourist attractions in the country.

The palace was among the first ...

, killed Queen Min, and desecrated her body in the north wing of the palace.

The Heungseon Daewongun returned to the royal palace the same day.

On 11 February 1896,

Gojong and the crown prince fled for protection at the Russian legation in Seoul, from which he governed for about a year.

Democracy protests and the proclamation of the Korean Empire

In 1896, various Korean activists formed the

Independence Club. They advocated a number of societal reforms, including democracy and a constitutional monarchy, and pushed for closer ties to Western countries in order to counterbalance Japanese influence. It went on to be influential in Korean politics for the short time that it operated, to the chagrin of Gojong. Gojong eventually forcefully disbanded the organization in 1898.

In October 1897, Gojong returned to the palace

Deoksugung

Deoksugung (), also called Deoksu Palace or Deoksugung Palace, is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. It was the first main palace of the 1897–1910 Korean Empire and is now a major tourist attraction. It has a mix of traditional Korea ...

, and proclaimed the founding of the

Korean Empire

The Korean Empire, officially the Empire of Korea or Imperial Korea, was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by King Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire lasted until the Japanese annexation of Korea in August 1910.

Dur ...

at the royal altar

Hwangudan. This symbolicly asserted Korea's independence from China, especially as Gojong demolished a reception hall that was once used to entertain Chinese ambassadors in order to build the altar.

Prelude to annexation

Having established economic and military dominance in Korea in October 1904, Japan reported that it had developed 25 reforms which it intended to introduce into Korea by gradual degrees. Among these was the intended acceptance by the Korean Financial Department of a Japanese Superintendent, the replacement of Korean Foreign Ministers and consuls by Japanese and the "union of military arms" in which the military of Korea would be modeled after the Japanese military. These reforms were forestalled by the prosecution of the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

from 8 February 1904, to 5 September 1905, which Japan won, thus eliminating Japan's last rival to influence in Korea.

Frustrated by this, King Gojong invited

Alice Roosevelt Longworth

Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth (February 12, 1884 – February 20, 1980) was an American writer and socialite. She was the eldest child of U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt and his only child with his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. Lo ...

, who was on a tour of Asian countries with

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, to the Imperial Palace on 20 September 1905, to seek political support from the United States despite her diplomatic rudeness. However, it was after exchanging opinions through the

Taft–Katsura agreement

The , also known as the Taft-Katsura Memorandum, was a 1905 discussion between senior leaders of Japan and the United States regarding the positions of the two nations in greater East Asian affairs, especially regarding the status of Korea and the ...

on 27 July 1905, that America and Japan would not interfere with each other on colonial issues.

Under the

Treaty of Portsmouth

The Treaty of Portsmouth is a treaty that formally ended the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. It was signed on September 5, 1905, after negotiations from August 6 to 30, at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, United States. U.S. P ...

, signed in September 1905, Russia acknowledged Japan's "paramount political, military, and economic interest" in Korea.

Two months later, Korea was obliged to become a Japanese protectorate by the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905, also known as the Eulsa Treaty, was made between delegates of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire in 1905. Negotiations were concluded on November 17, 1905. The treaty deprived Korea of its diplomatic s ...

and the "reforms" were enacted, including the reduction of the Korean Army from 20,000 to 1,000 men by disbanding all garrisons in the provinces, retaining only a single garrison in the precincts of Seoul.

On 6 January 1905, Horace Allen, head of the American Legation in Seoul reported to his Secretary of State, John Hay, that the Korean government had been advised by the Japanese government "that hereafter the police matters of Seoul will be controlled by the Japanese gendarmerie" and "that a Japanese police inspector will be placed in each prefecture". A large number of Koreans organized themselves in education and reform movements, but Japanese dominance in Korea had become a reality.

In June 1907, the

Second Peace Conference was held in

The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

. Emperor Gojong secretly sent three representatives to bring the problems of Korea to the world's attention. The three envoys, who questioned the legality of the protectorate convention, were

refused access to the public debates by the international delegates. One of these representatives was missionary and historian

Homer Hulbert. Out of despair, one of the Korean representatives,

Yi Tjoune

Yi Chun (; December 18, 1859 – July 14, 1907), name sometimes rendered Yi Tjoune, was a Korean prosecutor and diplomat and the father of the North Korean politician Lee Yong.

Early life

Yi Chun was born in 1859 in Pukchong County, South Ha ...

, committed suicide at The Hague. In response, the Japanese government took stronger measures. On 19 July 1907, Emperor Gojong was forced to relinquish his imperial authority and appoint the Crown Prince as regent. Japanese officials used this concession to force the accession of the new Emperor Sunjong following abdication, which was never agreed to by Gojong. Neither Gojong nor Sunjong were present at the 'accession' ceremony. Sunjong was to be the last ruler of the Joseon dynasty, founded in 1392.

On 24 July 1907, a treaty was signed under the leadership of

Lee Wan-yong

Yi Wanyong (; 17 July 1858 – 12 February 1926), also spelled Lee Wan-yong or Ye Wan-yong, was a Korean politician who served as the 7th Prime Minister of Korea. He is best remembered for signing the Eulsa Treaty and the Japan–Korea Ann ...

and

Ito Hirobumi

Ito, Itō or Itoh may refer to:

Places

* Ito Island, an island of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea

* Ito Airport, an airport in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Ito District, Wakayama, a district located in Wakayama Prefecture, Japa ...

to transfer all rights of

Korea to Japan. This led to a large-scale righteous army movement among Koreans, and disbanded troops joined the resistance forces. Japan's response to this was a scorched earth tactic using division-sized troops, which resulted in the movement of armed resistance organizations in Korea to Manchuria. Amid this confusion, on 26 October 1909,

Ahn Jung-geun, a former volunteer soldier, assassinated

Ito Hirobumi

Ito, Itō or Itoh may refer to:

Places

* Ito Island, an island of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea

* Ito Airport, an airport in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Ito District, Wakayama, a district located in Wakayama Prefecture, Japa ...

in

Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

.

Meanwhile, pro-Japanese populist groups such as the

Iljinhoe

The Iljinhoe (一進會; 일진회) was a nationwide organization in Korea formed on August 8, 1904. A Japanese record states the number of party members was about 800,000, but another survey record by the Japanese Resident-General of Korea in 19 ...

helped Japan by being fascinated by Japan's

pan-Asianism

file:Asia satellite orthographic.jpg , Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism) is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian people, Asian peo ...

, thinking that Korea would have autonomy like

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

.

It was adopted as a representative consultant for

Ryohei Uchida, and was used for propaganda with the support of the Japanese government. On 3 December 1909, he and

Lee Wan-yong

Yi Wanyong (; 17 July 1858 – 12 February 1926), also spelled Lee Wan-yong or Ye Wan-yong, was a Korean politician who served as the 7th Prime Minister of Korea. He is best remembered for signing the Eulsa Treaty and the Japan–Korea Ann ...

will issue a statement demanding the annexation of Korea.

However, the merger took place in the form of Japan's annexation of Korean territory and was disbanded by

Terauchi Masatake

'' Gensui'' Count Terauchi Masatake (), GCB (5 February 1852 – 3 November 1919), was a Japanese military officer and politician. He was a '' Gensui'' (or Marshal) in the Imperial Japanese Army and the prime minister of Japan from 1916 to 191 ...

on 26 September 1910.

Militant resistance

During the prelude to the 1910 annexation, a number of irregular civilian militias called "righteous armies" arose. They consisted of tens of thousands of peasants engaged in anti-Japanese armed rebellion. After the Korean army was disbanded in 1907, former soldiers joined the armies and fought the Japanese army at

Namdaemun

Namdaemun (), the Sungnyemun (), is one of the Eight Gates in the Seoul City Wall, South Korea. The gate formed the original southern boundary of the city during the Joseon period, although the city has since significantly outgrown this bou ...

. They were defeated, and largely fled into Manchuria, where they joined the guerrilla resistance movement that persisted until Korea's 1945 liberation.

Military police

As Korean resistance against Japanese rule intensified, Japanese replaced Korean police system with their military police. Infamous

Akashi Motojiro was appointed for the commander of Japanese military police forces. Japanese finally replaced Imperial Korean police forces in June 1910, and they combined police forces and military police, firmly establishing the rule of military police. After the annexation, Akashi started to serve as the Chief of Police. These military police officers started to have great authority over Koreans. Not only Japanese but also Koreans served as police officers.

Japan–Korea annexation treaty (1910)

In May 1910, the

Minister of War of Japan,

Terauchi Masatake

'' Gensui'' Count Terauchi Masatake (), GCB (5 February 1852 – 3 November 1919), was a Japanese military officer and politician. He was a '' Gensui'' (or Marshal) in the Imperial Japanese Army and the prime minister of Japan from 1916 to 191 ...

, was given a mission to finalize Japanese control over Korea after the previous treaties (the

Japan–Korea Treaty of February 1904

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1904 was made between representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire in 1904. Negotiations were concluded on 23 February 1904.Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington ...

and the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907 was made between the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire in 1907. Negotiations were concluded on July 24, 1907.Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, D.C., 1921-1922. (1922) ...

) had made Korea a protectorate of Japan and had established Japanese hegemony over Korean domestic politics. On 22 August 1910, Japan effectively

annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

Korea with the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, also known as the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty, was made by representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire on 22 August 1910. In this treaty, Japan formally annexed Korea following the J ...

signed by

Ye Wanyong, Prime Minister of Korea, and Terauchi Masatake, who became the first

Governor-General of Chōsen

The Governor-General of Chōsen (; ) was the chief administrator of the : a part of an administrative organ established by the Imperial government of Japan. The position existed from 1910 to 1945.

The governor-general of Chōsen was established ...

.

The treaty became effective the same day and was published one week later. The treaty stipulated:

* Article 1: His Majesty the Emperor of Korea concedes completely and definitely his entire sovereignty over the whole Korean territory to His Majesty the Emperor of Japan.

* Article 2: His Majesty the Emperor of Japan accepts the concession stated in the previous article and consents to the annexation of Korea to the Empire of Japan.

Both the protectorate and the annexation treaties were declared already void in the 1965

.

This period is also known as Military Police Reign Era (1910–19) in which Police had the authority to rule the entire country. Japan was in control of the media, law as well as government by physical power and regulations.

In March 2010, 109 Korean intellectuals and 105 Japanese intellectuals met in the 100th anniversary of

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, also known as the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty, was made by representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire on 22 August 1910. In this treaty, Japan formally annexed Korea following the J ...

and they declared this annexation treaty null and void. They declared these statements in each of their capital cities (Seoul and Tōkyō) with a simultaneous press conference. They announced the "Japanese empire pressured the outcry of the Korean Empire and people and forced by Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910 and full text of a treaty was false and text of the agreement was also false". They also declared the "Process and formality of "Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910" had huge deficiencies and therefore the treaty was null and void. This implied the

March First Movement

The March First Movement was a series of protests against Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese colonial rule that was held throughout Korea and internationally by the Korean diaspora beginning on March 1, 1919. Protests were largely concentrated in ...

was not an illegal movement.

Early years and expansion (1910–1941)

Japanese migration and land ownership

From around the time of the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, Japanese merchants started settling in towns and cities in Korea seeking economic opportunity. By 1908 the number of Japanese settlers in Korea was somewhere below the figure of 500,000, comprising one of the ''

nikkei'' communities in the world at the time.

Many Japanese settlers showed interest in acquiring agricultural land in Korea even before Japanese land-ownership was officially legalized in 1906. Governor-General Terauchi Masatake facilitated settlement through

land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

. The Korean land-ownership system featured absentee landlords, only partial owner-tenants and cultivators with traditional (but no legal proof of) ownership. By 1920, 90 percent of Korean land had proper ownership of Koreans. Terauchi's new Land Survey Bureau conducted

cadastral

A cadastre or cadaster ( ) is a comprehensive recording of the real estate or real property's metes and bounds, metes-and-bounds of a country.Jo Henssen, ''Basic Principles of the Main Cadastral Systems in the World,'/ref>

Often it is represente ...

surveys that established ownership on the basis of written proof (deeds, titles, and similar documents). The system denied ownership to those who could not provide such written documentation; these turned out to be mostly high-class and impartial owners who had only traditional verbal cultivator-rights . Japanese landlords included both individuals and corporations (such as the

Oriental Development Company). Because of these developments, Japanese landownership soared, as did the amount of land taken over by private Japanese companies. Many former Korean landowners, as well as agricultural workers, became

tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...

s, having lost their

entitlements

An entitlement is a government program guaranteeing access to some benefit by members of a specific group and based on established rights or by legislation. A "right" is itself an entitlement associated with a moral or social principle, while an ...

almost overnight because they could not pay for the land reclamation and irrigation improvements forced on them. Compounding the economic stresses imposed on the Korean peasantry, the authorities forced Korean peasants to do long days of compulsory labor to build irrigation works; Japanese imperial officials made peasants pay for these projects in the form of heavy taxes, impoverishing many of them and causing even more of them lose their land. Although many other subsequent developments placed ever greater strain on Korea's peasants, Japan's rice shortage in 1918 was the greatest catalyst for hardship. During that shortage, Japan looked to Korea for increased rice cultivation; as Korean peasants started producing more for Japan, however, the amount they took to eat dropped precipitously, causing much resentment among them.

By 1910 an estimated 7 to 8% of all

arable land

Arable land (from the , "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the purposes of a ...

in Korea had come under Japanese control. This ratio increased steadily; as of the years 1916, 1920, and 1932, the ratio of Japanese land ownership increased from 36.8 to 39.8 to 52.7%. The level of tenancy was similar to that of farmers in Japan itself; however, in Korea, the landowners were mostly Japanese, while the tenants were all Koreans. As often occurred in Japan itself, tenants had to pay over half their crop in rent.

By the 1930s the growth of the urban economy and the exodus of farmers to the cities had gradually weakened the hold of the landlords. With the growth of the wartime economy throughout the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the government recognized

landlordism

Concentration of land ownership refers to the ownership of land in a particular area by a small number of people or organizations. It is sometimes defined as additional concentration beyond that which produces optimally efficient land use.

Distr ...

as an impediment to increased agricultural productivity, and took steps to increase control over the rural sector through the formation in Japan in 1943 of the , a compulsory organization under the wartime

command economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

.

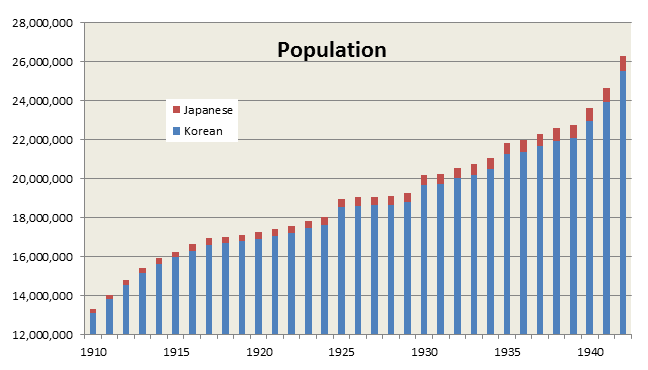

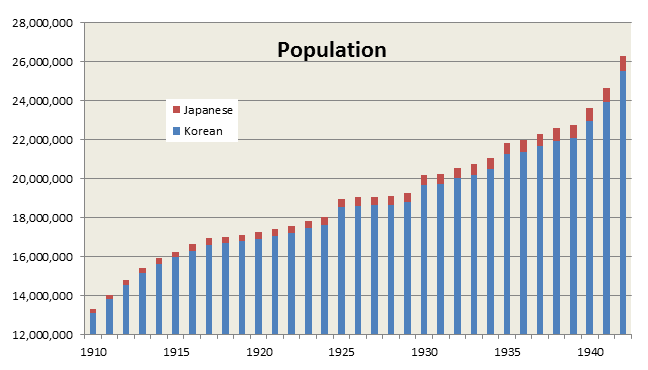

The Japanese government had hoped emigration to its colonies would mitigate the population boom in the ''

naichi''(内地),

but had largely failed to accomplish this by 1936.

According to figures from 1934, Japanese in Chōsen numbered approximately 561,000 out of a total population of over 21 million, less than 3%. By 1939 the Japanese population increased to 651,000, mostly from Japan's western prefectures. During the same period, the population in Chōsen grew faster than that in the ''naichi''. Koreans also migrated to the ''naichi'' in large numbers, especially after 1930; by 1939 there were over 981,000 Koreans living in Japan. Challenges which deterred Japanese from migrating into Chōsen included lack of arable land and population density comparable to that of Japan.

Anthropology and cultural heritage

Japan sent anthropologists to Korea who took photos of the traditional state of Korean villages, serving as evidence that Korea was "backwards" and needed to be modernized.

In 1925, the Japanese government established the

Korean History Compilation Committee

Korean History Compilation Committee () was established in June 1925 by the Japanese government

The Government of Japan is the central government of Japan. It consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and functions under t ...

, and it was administered by the Governor-General and engaged in collecting Korean historical materials and compiling Korean history. According to the ''

Doosan Encyclopedia

''Doosan Encyclopedia'' () is a Korean-language encyclopedia published by Doosan Donga (). The encyclopedia is based on the ''Dong-A Color Encyclopedia'' (), which comprises 30 volumes and began to be published in 1982 by Dong-A Publishing (). ...

'', some mythology was incorporated.

The committee supported the theory of a Japanese colony on the Korean Peninsula called

Mimana

Mimana (), also transliterated as Imna according to the Korean pronunciation, is the name used primarily in the 8th-century Japanese text '' Nihon Shoki'', likely referring to one of the Korean states of the time of the Gaya confederacy (c. 1st– ...

,

which, according to E. Taylor Atkins, is "among the most disputed issues in East Asian historiography."

Japan executed the first modern archaeological excavations in Korea. The Japanese administration also relocated some artifacts; for instance, a stone monument (棕蟬縣神祠碑), which was originally located in the

Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong or Liaotung Peninsula ( zh, s=辽东半岛, t=遼東半島, p=Liáodōng Bàndǎo) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located ...

, then under

Japanese control, was taken out of its context and moved to

Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

. As of April 2020, 81,889 Korean cultural artifacts are in Japan. According to the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation, not all the artifacts were moved illegally. Adding to the challenge of repatriating illegally exported Korean cultural properties is the lack of experts in Korean art at overseas museums and institutions, alterations made to artifacts that obscure their origin, and that moving Korean artifacts within what was previously internationally recognized Japanese territory was lawful at the time.

The South Korean government has been continuing its efforts to repatriate Korean artifacts from museums and private collections overseas.

The royal palace

Gyeongbokgung

Gyeongbokgung () is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. Established in 1395, it was the first royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and is now one of the most significant tourist attractions in the country.

The palace was among the first ...

was partially destroyed beginning in the 1910s, in order to make way for the

Japanese General Government Building

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

as well as the colonial

Chōsen Industrial Exhibition.

Hundreds of historic buildings in

Deoksugung

Deoksugung (), also called Deoksu Palace or Deoksugung Palace, is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. It was the first main palace of the 1897–1910 Korean Empire and is now a major tourist attraction. It has a mix of traditional Korea ...

were also destroyed to make way for the . The displays in the museum reportedly intentionally contrasted traditional Korean art with examples of modern Japanese art, in order to portray Japan as progressive and legitimize Japanese rule.

The

National Palace Museum of Korea

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

, originally built as the Korean Imperial Museum in 1908 to preserve the treasures in the

Gyeongbokgung

Gyeongbokgung () is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. Established in 1395, it was the first royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and is now one of the most significant tourist attractions in the country.

The palace was among the first ...

, was retained under the Japanese administration but renamed Museum of the Yi Dynasty in 1938.

The Governor-General instituted a law in 1933 in order to preserve Korea's most important historical artifacts. The system established by this law, retained as the present-day

National Treasures of South Korea

National Treasure () is a national-level designation within the heritage preservation system of South Korea for tangible objects of significant artistic, cultural and historical value. Examples of objects include art, artifacts, sites, or buildi ...

and

National Treasures of North Korea

A National Treasure () is a tangible artifact, site, or building deemed by the Government of North Korea to have significant historical or artistic value to the country.

History

The first list of Korean cultural treasures was designated by Gover ...

, was intended to preserve Korean historical artifacts, including those not yet unearthed. Japan's 1871 Edict for the Preservation of Antiquities and Old Items could not be automatically applied to Korea due to Japanese law, which required an imperial ordinance to apply the edict in Korea. The 1933 law to protect Korean cultural heritages was based on the Japanese 1871 edict.

[Ohashi Toshihiro.]

A Study on the Development of the Cultural Properties Policy in Korea from 1902 until 1962

". ''Sogo Seisaku Ronso'' 8 (2004)

Anti-Chinese riots of 1931

Due to a waterway construction permit, in the small town of Wanpaoshan in Manchuria near

Changchun

Changchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin, Jilin Province, China, on the Songliao Plain. Changchun is administered as a , comprising seven districts, one county and three county-level cities. At the 2020 census of China, Changchun ha ...

, "violent clashes" broke out between the local Chinese and Korean immigrants on 2 July 1931. ''

The Chosun Ilbo

''The Chosun Ilbo'' (, ), also known as ''The Chosun Daily,'' is a Korean-language newspaper of record for South Korea and among the oldest active newspapers in the country. With a daily circulation of more than 1,800,000, ''The'' ''Chosun Ilbo ...

'', a major Korean newspaper, misreported that many Koreans had died in the clashes, sparking a Chinese exclusion movement in urban areas of the Korean Peninsula. The worst of the rioting occurred in

Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

on 5 July. Approximately 127 Chinese people were killed, 393 wounded, and a considerable number of properties were destroyed by Korean residents.

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

further alleged the Japanese authorities in Korea did not take adequate steps to protect the lives and property of the Chinese residents, and blamed the authorities for allowing inflammatory accounts to be published. As a result of this riot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs

Kijūrō Shidehara

Baron was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1945 to 1946. He was a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II.

Born to a wealthy Osaka family, Shidehara studied law at Tok ...

, who insisted on Japanese, Chinese, and Korean harmony, lost his position.

Order to change names

In 1911, the proclamation "Matter Concerning the Changing of Korean Names" (') was issued, barring ethnic Koreans from taking Japanese names and retroactively reverting the names of Koreans who had already registered under Japanese names back to the original Korean ones.

By 1939, however, this position was reversed and Japan's focus had shifted towards

cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

of the Korean people; Imperial Decree 19 and 20 on Korean Civil Affairs (

Sōshi-kaimei

was a policy of pressuring Koreans under Japanese rule to adopt Japanese names and identify as such. The primary reason for the policy was to forcibly assimilate Koreans, as was done with the Ainu and the Ryukyuans. The Sōshi-kaimei has been ...

) went into effect, whereby ethnic Koreans were forced to surrender their traditional use of clan-based

Korean family name

This is a list of Korean surnames, in Hangul alphabetical order.

The most common Korean surname (particularly in South Korea) is Kim (Korean name), Kim (), followed by Lee (Korean name), Lee () and Park (Korean surname), Park (). These three sur ...

system, in favor of a new surname to be used in the family register. The surname could be of their own choosing, including their native clan name, but in practice many Koreans received a Japanese surname. There is controversy over whether or not the adoption of a Japanese surname was effectively mandatory, or merely strongly encouraged.

World War II

National Mobilization Law

Forcing of labor and migration

From 1939,

labor shortage

In economics, a shortage or excess demand is a situation in which the demand for a product or service exceeds its supply in a market. It is the opposite of an excess supply ( surplus).

Definitions

In a perfect market (one that matches a s ...

s as a result of

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

of Japanese men for the military efforts of World War II led to organized official recruitment of Koreans to work in mainland Japan, initially through civilian agents, and later directly, often involving elements of coercion. As the labor shortage increased, by 1942, the Japanese authorities extended the provisions of the

National Mobilization Law

The , also known as the National Mobilization Law, was legislated in the Diet of Japan by Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on 24 March 1938 to put the national economy of the Empire of Japan on War economy, war-time footing ...

to include the conscription of Korean workers for factories and mines in Korea,

Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially known as the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of Great Manchuria thereafter, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China that existed from 1932 until its dissolution in 1945. It was ostens ...

, and the involuntary relocation of workers to Japan itself as needed.

The combination of immigrants and forced laborers during World War II brought the total to over 2 million Koreans in Japan by the end of the war, according to estimates by the

Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (), or SCAP, was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) ...

.

Of the 5,400,000 Koreans conscripted, about 670,000 were taken to mainland Japan (including

Karafuto Prefecture

, was established by the Empire of Japan in 1907 to govern the southern part of Sakhalin. This territory became part of the Empire of Japan in 1905 after the Russo-Japanese War, when the portion of Sakhalin south of 50°N was ceded by the R ...

, present-day

Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

, now part of Russia) for civilian labor. Those who were brought to Japan were often forced to work under conditions that have been described as appalling and dangerous. Although Koreans were reportedly treated better than laborers from other countries, large numbers still died. In Japan, 60,000 of the 670,000 mobilized laborers died. In Korea and Manchuria, estimates of deaths range between 270,000 and 810,000.

[

Available online: ]

Korean laborers were also found as far as the

Tarawa Atoll

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Kiribati, Republic of Kiribati,[Kiribati](_blank)

''The World ...

, where during the

Battle of Tarawa

The Battle of Tarawa was fought on 20–23 November 1943 between the United States and Japan on Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, and was part of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. invasion of the Gilberts. Nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans, and Am ...

only 129 of the 1200 laborers survived. According to testimonies in Japanese records, Korean laborers on the

Mili Atoll

Mili Atoll ( Marshallese: , ) is a coral atoll of 92 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands. It is located approximately southeast of Arno. Its total land area is making it th ...

were given "whale meat" to consume, which was actually human flesh from other dead Koreans. They rebelled after learning the truth, and were killed by the dozens in the aftermath.

Korean laborers also worked in Korea itself, notably in

Jeju where in the later stages of the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, Korean laborers expanded airfields and built facilities at

Altteureu Airfield in order to block a US invasion of the Japanese mainland and in 1945 laborers on

Songaksan (where several airstrips were located) were ordered to smooth down the slope in order to prevent American tanks being able to go up.

Most Korean atomic-bomb victims in Japan had been drafted for work at military industrial factories in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the name of humanitarian assistance, Japan paid South Korea four billion yen (approx. thirty five million dollars) and built a welfare center for those suffering from the effects of the atomic bomb.

Korean service in the Japanese military

Japan did not draft ethnic Koreans into its military until 1944 when the tide of World War II turned against it. Until 1944, enlistment in the

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

by ethnic Koreans was voluntary, and highly competitive. From a 14% acceptance rate in 1938, it dropped to a 2% acceptance rate in 1943 while the raw number of applicants increased from 3000 per annum to 300,000 in just five years during World War II.

Other Korean officers who served Japan moved on to successful careers in post-colonial South Korea. Examples include

Park Chung Hee

Park Chung Hee (; ; November14, 1917October26, 1979) was a South Korean politician and army officer who served as the third president of South Korea from 1962 after he seized power in the May 16 coup of 1961 until Assassination of Park Chung ...

, who became president of South Korea;

Chung Il-kwon, prime minister from 1964 to 1970;

Paik Sun-yup

Paik Sun-yup (; November 23, 1920 – July 10, 2020) was a Republic of Korea Army four-star general who became the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1959 to 1960. Paik is best known for his service during the Korean War, becoming the ...

, South Korea's youngest general who was famous for his command of the

1st Infantry Division during the

defense of the Pusan Perimeter, and

Kim Suk-won, a colonel of the Imperial Japanese Army who subsequently became a general of the South Korean army. The first ten of the Chiefs of Army Staff of South Korea graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and none from the

Korean Liberation Army

The Korean Liberation Army (KLA; ), also known as the Korean Restoration Army, was the armed forces of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. It was established on September 17, 1940, in Chongqing, Republic of China (1912–1949), ...

.

Officer cadets had been joining the Japanese Army since before the annexation by attending the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. Enlisted Soldier recruitment began as early as 1938, when the Japanese

Kwantung Army

The Kwantung Army (Japanese language, Japanese: 関東軍, ''Kantō-gun'') was a Armies of the Imperial Japanese Army, general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1919 to 1945.

The Kwantung Army was formed in 1906 as a security force for th ...

in Manchuria began accepting pro-Japanese Korean volunteers into the army of Manchukuo, and formed the

Gando Special Force. Koreans in this unit specialized in counter-insurgency operations against communist guerillas in the region of

Jiandao

Jiandao or Chientao, known in Korean as Gando or Kando, is a historical border region along the north bank of the Tumen River in Jilin, Jilin Province, Northeast China that has a high population of ethnic Koreans. The word "Jiandao", literall ...

. The size of the unit grew considerably at an annual rate of 700 men, and included such notable Koreans as General

Paik Sun-yup

Paik Sun-yup (; November 23, 1920 – July 10, 2020) was a Republic of Korea Army four-star general who became the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1959 to 1960. Paik is best known for his service during the Korean War, becoming the ...

, who served in the Korean War. Historian Philip Jowett noted that during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, the

Gando Special Force "earned a reputation for brutality and was reported to have laid waste to large areas which came under its rule".

Starting in 1944, Japan started the

conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

of Koreans into the armed forces. All Korean men were drafted to either join the Imperial Japanese Army, as of April 1944, or work in the military industrial sector, as of September 1944. Before 1944, 18,000 Koreans passed the examination for induction into the army. Koreans provided workers to mines and construction sites around Japan. The number of conscripted Koreans reached its peak in 1944 in preparation for war. From 1944, about 200,000 Korean men were inducted into the army.

During World War II, American soldiers frequently encountered Korean soldiers within the ranks of the Imperial Japanese Army. Most notably was in the

Battle of Tarawa

The Battle of Tarawa was fought on 20–23 November 1943 between the United States and Japan on Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, and was part of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. invasion of the Gilberts. Nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans, and Am ...

, which was considered during that time to be one of the bloodiest battles in U.S. military history. A fifth of the Japanese garrison during this battle consisted of Korean laborers, where on the last night of the battle a combined 300 Japanese soldiers and Korean laborers did a last ditch charge. Like their Japanese counterparts, many of them were killed.

The Japanese, however, did not always believe they could rely on Korean laborers to fight alongside them. In ''Prisoners of the Japanese'', author Gaven Daws wrote, "

Tinian

Tinian () is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the four constituent municipalities of the Northern ...

there were five thousand Korean laborers and so as not to have hostiles ''at their back'' when the Americans invaded, the Japanese killed them."

After the war, 148 Koreans were convicted of Class B and C

Japanese war crimes

During its imperial era, Empire of Japan, Japan committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity across various Asian-Pacific nations, notably during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents ...

, 23 of whom were sentenced to death (compared to 920 Japanese who were sentenced to death), including Korean prison guards who were particularly notorious for their brutality during the war. The figure is relatively high considering that ethnic Koreans made up a small percentage of the Japanese military. Judge

Bert Röling

Bernard Victor Aloysius "Bert" Röling (26 December 1906 – 16 March 1985) was a Dutch jurist and founding father of polemology in the Netherlands. Between 1946 and 1948 he acted as the Dutch representative for the International Military Tribu ...

, who represented the Netherlands at the

International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on 29 April 1946 to Criminal procedure, try leaders of the Empire of Japan for their cri ...

, noted that "many of the commanders and guards in POW camps were Koreans – the Japanese apparently did not trust them as soldiers – and it is said that they were sometimes far more cruel than the Japanese." In his memoirs, Colonel Eugene C. Jacobs wrote that during the

Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March was the Death march, forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of around 72,000 to 78,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POWs) from the municipalities of Bagac and Mariveles on the Bataan Peninsula to Camp ...

, "the Korean guards were the most abusive. The Japanese didn't trust them in battle, so used them as service troops; the Koreans were anxious to get blood on their bayonets; and then they thought they were veterans."

Korean guards were sent to the remote jungles of

Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, where Lt. Col. William A. (Bill) Henderson wrote from his own experience that some of the guards overseeing the construction of the

Burma Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

"were moronic and at times almost bestial in their treatment of prisoners. This applied particularly to Korean private soldiers, conscripted only for guard and sentry duties in many parts of the Japanese empire. Regrettably, they were appointed as guards for the prisoners throughout the camps of Burma and Siam." The highest-ranking Korean to be prosecuted after the war was Lieutenant General

Hong Sa-ik, who was in command of all the Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in the Philippines.

Comfort women

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, many ethnic Korean girls and women (mostly aged 12–17) were forced by the Japanese military to become sex slaves on the pretext of being hired for jobs, such as a seamstresses or factory workers, and were forced to provide sexual service for Japanese soldiers by agencies or their families against their wishes. These women were euphemistically called "

comfort women

Comfort women were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term ''comfort women'' is a translation of the Japanese , a euphemism ...

".

According to an interrogation report by

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

in 1944, comfort women were in good physical health. They were able to have a periodic checkup once a week and to receive treatment in case of spreading disease to the Japanese soldiers, but not for their own health. However, a 1996

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

Report detailed that "large numbers of women were forced to submit to prolonged prostitution under conditions which were frequently indescribably traumatic". Documents which survived the war revealed "beyond doubt the extent to which the Japanese forces took direct responsibility for the comfort stations" and that the published practices were "in stark contrast with the brutality and cruelty of the practice".

Chizuko Ueno at

Kyoto University

, or , is a National university, national research university in Kyoto, Japan. Founded in 1897, it is one of the former Imperial Universities and the second oldest university in Japan.

The university has ten undergraduate faculties, eighteen gra ...

cautions against the claim that women were not forced as the fact that "no positive sources exist supporting claims that comfort women were forced labor" must be treated with doubt, as "it is well known that the great majority of potentially damaging official documents were destroyed in anticipation of the Allied occupation".

The

Asian Women's Fund

The , also abbreviated to in Japanese, was a fund set up by the Japanese government in 1994 to distribute monetary compensation to comfort women in South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, the Netherlands, and Indonesia.Asian Women's Fund Online Mus ...

claimed that during World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army recruited anywhere from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of women from occupied territories to be used as sex slaves.

Yoshimi Yoshiaki asserted that possibly hundreds of thousands of girls and women, mainly from China and the Korean Peninsula but also Southeast Asian countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army, as well as Australia and the Netherlands, were forced to serve as comfort women. According to testimonies, young women were abducted from their homes in countries under Imperial Japanese rule. In many cases, women were lured with promises of work in factories or restaurants. In some cases propaganda advocated equity and the sponsorship of women in higher education. Other enticements were false advertising for nursing jobs at outposts or Japanese army bases; once recruited, they were incarcerated in comfort stations both inside their nations and abroad.

From the early nineties onward, former Korean comfort women have continued to protest against the Japanese government for apparent historical negationism of crimes committed by the

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

, and have sought compensation for their sufferings during the war. There has also been international support for compensation, such as from the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, the Netherlands, Canada and the Philippines. The United States passed

House of Representatives House Resolution 121 on 30 July 2007, asking the Japanese government to redress the situation and to incorporate comfort women into school curriculum.

Hirofumi Hayashi at the

University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

argues that the resolution has helped to counter the "arguments of ultrarightists flooding the mainstream mass media" and warned against the rationalization of the comfort women system.

Religion and ideology

Protestant Christian missionary efforts in Asia were quite successful in Korea. American Presbyterians and Methodists arrived in the 1880s and were well received. They served as medical and educational missionaries, establishing schools and hospitals in numerous cities. In the years when Korea was under Japanese control, some Koreans adopted Christianity as an expression of nationalism in opposition to the Japan's efforts to promote the Japanese language and the Shinto religion.

[Danielle Kane, and Jung Mee Park, "The Puzzle of Korean Christianity: Geopolitical Networks and Religious Conversion in Early Twentieth-Century East Asia", ''American Journal of Sociology'' (2009) 115#2 pp 365–404]

In 1914 of 16 million Koreans, there were 86,000 Protestants and 79,000 Catholics. By 1934 the numbers were 168,000 and 147,000, respectively. Presbyterian missionaries were especially successful. Harmonizing with traditional practices became an issue. The Protestants developed a substitute for Confucian ancestral rites by merging Confucian-based and Christian death and funerary rituals.

Korean independence movement

Guerrilla resistance in Manchuria and Russia

Since the early 1900s, Koreans in

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

and

Primorsky Krai

Primorsky Krai, informally known as Primorye, is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (a krais of Russia, krai) of Russia, part of the Far Eastern Federal District in the Russian Far East. The types of inhabited localities in Russia, ...

in Russia waged a guerrilla war against the Japanese occupation. At this time,

Beom-do Hong's unit ambushed and annihilated the Imperial Japanese Army that was advancing in

Battle of Bongodong(Fengwudong),

Jilin

)

, image_skyline = Changbaishan Tianchi from western rim.jpg

, image_alt =

, image_caption = View of Heaven Lake

, image_map = Jilin in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_al ...

,

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

(June

1920

Events January

* January 1

** Polish–Soviet War: The Russian Red Army increases its troops along the Polish border from 4 divisions to 20.

** Kauniainen in Finland, completely surrounded by the city of Espoo, secedes from Espoo as its ow ...

). Also, the combined forces of the independence army commanded by

Kim Chwajin and

Hong Beom-do, while repeatedly retreating operationally, ambushed and killed about 1,500 Imperial Japanese soldiers in