Chain Home on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal

Since 1915, Robert Watson-Watt had been working for the Met Office in a lab that was colocated at the National Physical Laboratory's (NPL) Radio Research Section (RRS) at Ditton Park in Slough. Watt became interested in using the fleeting radio signals given off by

Since 1915, Robert Watson-Watt had been working for the Met Office in a lab that was colocated at the National Physical Laboratory's (NPL) Radio Research Section (RRS) at Ditton Park in Slough. Watt became interested in using the fleeting radio signals given off by

At the same time, the need for such a system was becoming increasingly pressing. In 1932,

At the same time, the need for such a system was becoming increasingly pressing. In 1932,

In 1923–24 inventor Harry Grindell Matthews repeatedly claimed to have built a device that projected energy over long ranges and attempted to sell it to the War Office, but it was deemed to be fraudulent. His attempts spurred on many other inventors to contact the British military with claims of having perfected some form of the fabled electric or radio " death ray". Some turned out to be frauds and none turned out to be feasible.

Around the same time, a series of stories suggested another radio weapon was being developed in Germany. The stories varied, with one common thread being a death ray, and another that used the signals to interfere with an engine's

In 1923–24 inventor Harry Grindell Matthews repeatedly claimed to have built a device that projected energy over long ranges and attempted to sell it to the War Office, but it was deemed to be fraudulent. His attempts spurred on many other inventors to contact the British military with claims of having perfected some form of the fabled electric or radio " death ray". Some turned out to be frauds and none turned out to be feasible.

Around the same time, a series of stories suggested another radio weapon was being developed in Germany. The stories varied, with one common thread being a death ray, and another that used the signals to interfere with an engine's

Watt wrote back to the committee saying the death ray was extremely unlikely, but added:

The letter was discussed at the first official meeting of the Tizard Committee on 28 January 1935. The utility of the concept was evident to all attending, but the question remained whether it was actually possible. Albert Rowe and Wimperis both checked the maths and it appeared to be correct. They immediately wrote back asking for a more detailed consideration. Watt and Wilkins followed up with a 14 February secret memo entitled ''Detection and Location of Aircraft by Radio Means''. In the new memo, Watson-Watt and Wilkins first considered various natural emanations from the aircraft – light, heat and radio waves from the engine ignition system – and demonstrated that these were too easy for the enemy to mask to a level that would be undetectable at reasonable ranges. They concluded that radio waves from their own transmitter would be needed.

Wilkins gave specific calculations for the expected reflectivity of an aircraft. The received signal would be only 10−19 times as strong as the transmitted one, but such sensitivity was considered to be within the state of the art. To reach this goal, a further improvement in receiver sensitivity of two times was assumed. Their ionospheric systems broadcast only about 1 kW, but commercial shortwave systems were available with 15 amp transmitters (about 10 kW) that they calculated would produce a signal detectable at about . They went on to suggest that the output power could be increased as much as ten times if the system operated in pulses instead of continuously, and that such a system would have the advantage of allowing range to the targets to be determined by measuring the time delay between transmission and reception on an

Watt wrote back to the committee saying the death ray was extremely unlikely, but added:

The letter was discussed at the first official meeting of the Tizard Committee on 28 January 1935. The utility of the concept was evident to all attending, but the question remained whether it was actually possible. Albert Rowe and Wimperis both checked the maths and it appeared to be correct. They immediately wrote back asking for a more detailed consideration. Watt and Wilkins followed up with a 14 February secret memo entitled ''Detection and Location of Aircraft by Radio Means''. In the new memo, Watson-Watt and Wilkins first considered various natural emanations from the aircraft – light, heat and radio waves from the engine ignition system – and demonstrated that these were too easy for the enemy to mask to a level that would be undetectable at reasonable ranges. They concluded that radio waves from their own transmitter would be needed.

Wilkins gave specific calculations for the expected reflectivity of an aircraft. The received signal would be only 10−19 times as strong as the transmitted one, but such sensitivity was considered to be within the state of the art. To reach this goal, a further improvement in receiver sensitivity of two times was assumed. Their ionospheric systems broadcast only about 1 kW, but commercial shortwave systems were available with 15 amp transmitters (about 10 kW) that they calculated would produce a signal detectable at about . They went on to suggest that the output power could be increased as much as ten times if the system operated in pulses instead of continuously, and that such a system would have the advantage of allowing range to the targets to be determined by measuring the time delay between transmission and reception on an

The letter was seized on by the Committee, who immediately released £4,000 to begin development. They petitioned Hugh Dowding, the Air Member for Supply and Research, to ask the Treasury for another £10,000. Dowding was extremely impressed with the concept, but demanded a practical demonstration before further funding was released.

Wilkins suggested using the new 10 kW, 49.8 m

The letter was seized on by the Committee, who immediately released £4,000 to begin development. They petitioned Hugh Dowding, the Air Member for Supply and Research, to ask the Treasury for another £10,000. Dowding was extremely impressed with the concept, but demanded a practical demonstration before further funding was released.

Wilkins suggested using the new 10 kW, 49.8 m

In August 1935, Albert Rowe, secretary of the Tizard Committee, coined the term "Radio Direction and Finding" (RDF), deliberately choosing a name that could be confused with "Radio Direction Finding", a term already in widespread use.

In a 9 September 1935 memo, Watson-Watt outlined the progress to date. At that time the range was about , so Watson-Watt suggested building a complete network of stations apart along the entire east coast. Since the transmitters and receivers were separate, to save development costs he suggested placing a transmitter at every other station. The transmitter signal could be used by a receiver at that site as well as the ones on each side of it. This was quickly rendered moot by the rapid increases in range. When the Committee next visited the site in October, the range was up to , and Wilkins was working on a method for height finding using multiple antennas.

In spite of its ''ad hoc'' nature and short development time of less than six months, the Orfordness system had already become a useful and practical system. In comparison, the acoustic mirror systems that had been in development for a decade were still limited to only range under most conditions, and were very difficult to use in practice. Work on mirror systems ended, and on 19 December 1935, a £60,000 contract for five RDF stations along the south-east coast was sent out, to be operational by August 1936.

The only person not convinced of the utility of RDF was Lindemann. He had been placed on the Committee at the insistence of his friend, Churchill, and proved unimpressed with the team's work. When he visited the site, he was upset by the crude conditions, and apparently, by the box lunch he had to eat. Lindemann strongly advocated the use of

In August 1935, Albert Rowe, secretary of the Tizard Committee, coined the term "Radio Direction and Finding" (RDF), deliberately choosing a name that could be confused with "Radio Direction Finding", a term already in widespread use.

In a 9 September 1935 memo, Watson-Watt outlined the progress to date. At that time the range was about , so Watson-Watt suggested building a complete network of stations apart along the entire east coast. Since the transmitters and receivers were separate, to save development costs he suggested placing a transmitter at every other station. The transmitter signal could be used by a receiver at that site as well as the ones on each side of it. This was quickly rendered moot by the rapid increases in range. When the Committee next visited the site in October, the range was up to , and Wilkins was working on a method for height finding using multiple antennas.

In spite of its ''ad hoc'' nature and short development time of less than six months, the Orfordness system had already become a useful and practical system. In comparison, the acoustic mirror systems that had been in development for a decade were still limited to only range under most conditions, and were very difficult to use in practice. Work on mirror systems ended, and on 19 December 1935, a £60,000 contract for five RDF stations along the south-east coast was sent out, to be operational by August 1936.

The only person not convinced of the utility of RDF was Lindemann. He had been placed on the Committee at the insistence of his friend, Churchill, and proved unimpressed with the team's work. When he visited the site, he was upset by the crude conditions, and apparently, by the box lunch he had to eat. Lindemann strongly advocated the use of

The system was deliberately developed using existing commercially available technology to speed introduction. The development team could not afford the time to develop and debug new technology. Watt, a pragmatic engineer, believed "third-best" would do if "second-best" would not be available in time and "best" never available at all. This led to the use of the 50 m wavelength (around 6 MHz), which Wilkins suggested would resonate in a bomber's wings and improve the signal. Unfortunately, this also meant that the system was increasingly blanketed by noise as new commercial broadcasts began taking up this formerly high-frequency spectrum. The team responded by reducing their own wavelength to 26 m (around 11 MHz) to get clear spectrum. To everyone's delight, and contrary to Wilkins' 1935 calculations, the shorter wavelength produced no loss of performance. This led to a further reduction to 13 m, and finally the ability to tune between 10 and 13 m, (roughly 30-20 MHz) to provide some frequency agility to help avoid jamming.

Wilkins' method of height-finding was added in 1937. He had originally developed this system as a way to measure the vertical angle of transatlantic broadcasts while working at the RRS. The system consisted of several parallel dipoles separated vertically on the receiver masts. Normally the RDF goniometer was connected to two crossed dipoles at the same height and used to determine the bearing to a target return. For height finding, the operator instead connected two antennas at different heights and carried out the same basic operation to determine the vertical angle. Because the transmitter antenna was deliberately focused vertically to improve gain, a single pair of such antennas would only cover a thin vertical angle. A series of such antennas was used, each pair with a different centre angle, providing continuous coverage from about 2.5 degrees over the horizon to as much as 40 degrees above it. With this addition, the final remaining piece of Watt's original memo was accomplished and the system was ready to go into production.

Industry partners were canvassed in early 1937, and a production network was organized covering many companies.

The system was deliberately developed using existing commercially available technology to speed introduction. The development team could not afford the time to develop and debug new technology. Watt, a pragmatic engineer, believed "third-best" would do if "second-best" would not be available in time and "best" never available at all. This led to the use of the 50 m wavelength (around 6 MHz), which Wilkins suggested would resonate in a bomber's wings and improve the signal. Unfortunately, this also meant that the system was increasingly blanketed by noise as new commercial broadcasts began taking up this formerly high-frequency spectrum. The team responded by reducing their own wavelength to 26 m (around 11 MHz) to get clear spectrum. To everyone's delight, and contrary to Wilkins' 1935 calculations, the shorter wavelength produced no loss of performance. This led to a further reduction to 13 m, and finally the ability to tune between 10 and 13 m, (roughly 30-20 MHz) to provide some frequency agility to help avoid jamming.

Wilkins' method of height-finding was added in 1937. He had originally developed this system as a way to measure the vertical angle of transatlantic broadcasts while working at the RRS. The system consisted of several parallel dipoles separated vertically on the receiver masts. Normally the RDF goniometer was connected to two crossed dipoles at the same height and used to determine the bearing to a target return. For height finding, the operator instead connected two antennas at different heights and carried out the same basic operation to determine the vertical angle. Because the transmitter antenna was deliberately focused vertically to improve gain, a single pair of such antennas would only cover a thin vertical angle. A series of such antennas was used, each pair with a different centre angle, providing continuous coverage from about 2.5 degrees over the horizon to as much as 40 degrees above it. With this addition, the final remaining piece of Watt's original memo was accomplished and the system was ready to go into production.

Industry partners were canvassed in early 1937, and a production network was organized covering many companies.

During the summer of 1936, experiments were carried out at RAF Biggin Hill to examine what effect the presence of radar would have on an air battle. Assuming RDF would provide them 15 minutes' warning, they developed interception techniques putting fighters in front of the bombers with increasing efficiency. They found the main problems were finding their own aircraft's location, and ensuring the fighters were at the right altitude.

In a similar test against the operational radar at Bawdsey in 1937, the results were comical. As Dowding watched the ground controllers scramble to direct their fighters, he could hear the bombers passing overhead. He identified the problem not as a technological one, but in the reporting. The pilots were being sent too many reports, often contradictory. This realization led to the development of the Dowding system, an extensive network of telephone lines reporting to a central "filter room" in London where the reports from the radar stations were collected and collated, and fed back to the pilots in a clear format. The system as a whole was enormously manpower intensive.

By the outbreak of war in September 1939, there were 21 operational Chain Home stations. After the

During the summer of 1936, experiments were carried out at RAF Biggin Hill to examine what effect the presence of radar would have on an air battle. Assuming RDF would provide them 15 minutes' warning, they developed interception techniques putting fighters in front of the bombers with increasing efficiency. They found the main problems were finding their own aircraft's location, and ensuring the fighters were at the right altitude.

In a similar test against the operational radar at Bawdsey in 1937, the results were comical. As Dowding watched the ground controllers scramble to direct their fighters, he could hear the bombers passing overhead. He identified the problem not as a technological one, but in the reporting. The pilots were being sent too many reports, often contradictory. This realization led to the development of the Dowding system, an extensive network of telephone lines reporting to a central "filter room" in London where the reports from the radar stations were collected and collated, and fed back to the pilots in a clear format. The system as a whole was enormously manpower intensive.

By the outbreak of war in September 1939, there were 21 operational Chain Home stations. After the

Some of the steel transmitter towers remain, although the wooden receiver towers have all been demolished. The remaining towers have various new uses and in some cases are now protected as

Some of the steel transmitter towers remain, although the wooden receiver towers have all been demolished. The remaining towers have various new uses and in some cases are now protected as

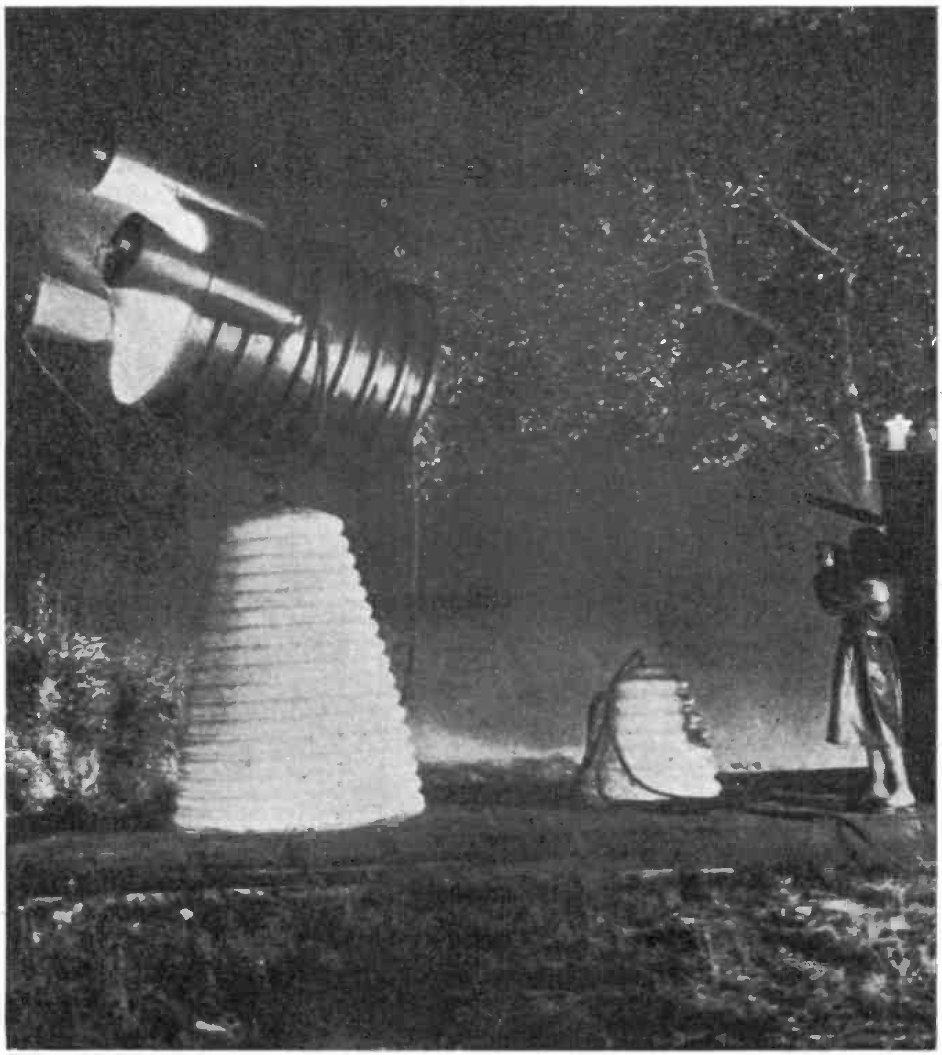

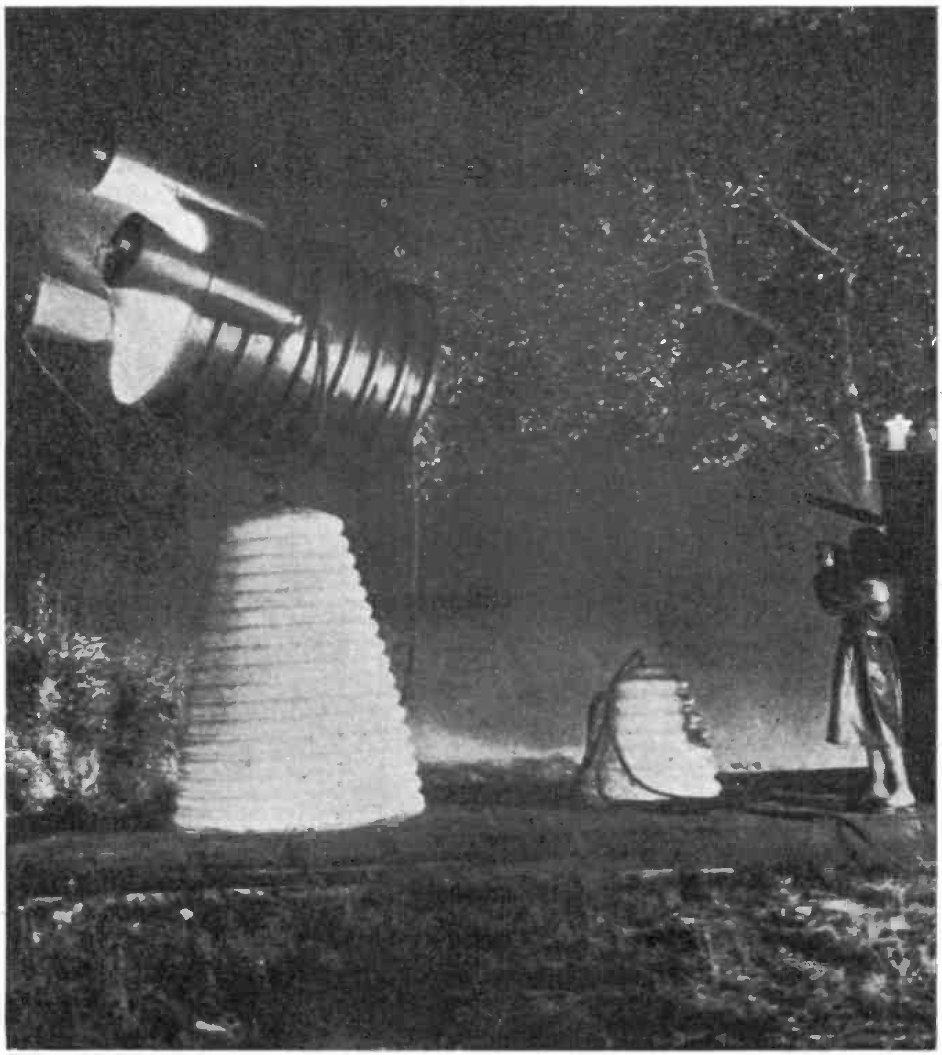

Operation began with the Type T.3026 transmitter sending a pulse of radio energy into the transmission antennas from a hut beside the towers. Each station had two T.3026's, one active and one standby. The signal filled space in front of the antenna, flooding the entire area. Due to the transmission effects of the multiple stacked antennas, the signal was most strong directly along the line of shoot, and dwindled on either side. An area about 50 degrees to either side of the line was filled with enough energy to make detection practical.

The Type T.3026 transmitter was provided by Metropolitan-Vickers, based on a design used for a BBC transmitter at Rugby. A unique feature of the design was the "demountable" valves, which could be opened for service, and had to be connected to an oil diffusion vacuum pump for continual evacuation while in use. The valves were able to operate at one of four selected frequencies between 20 and 55 MHz, and switched from one to another in 15 seconds. To produce the short pulses of signal, the transmitter consisted of Hartley oscillators feeding a pair of tetrode amplifier valves. The tetrodes were switched on and off by a pair of mercury vapour thyratrons connected to a timing circuit, the output of which biased the control and screen grids of the tetrode positively while a bias signal kept it normally turned off.

Stations were arranged so their fan-shaped broadcast patterns slightly overlapped to cover gaps between the stations. However, it was found that the timers controlling the broadcasts could drift and the broadcasts from one station would begin to be seen at others, a phenomenon known as "running rabbits". To avoid this, power from the National Grid was used to provide a convenient phase-locked 50 Hz signal that was available across the entire nation. Each CH station was equipped with a phase-shifting transformer that triggered it at a different point on the grid waveform. The output of the transformer was fed to a Dippy oscillator that produced sharp pulses at 25 Hz, phase-locked to the output from the transformer. The locking was "soft", so short-term variations in the phase or frequency of the grid were filtered out.

During times of strong ionospheric reflection, especially at night, it was possible that the receiver would see reflections from the ground after one reflection. To address this problem, the system was later provided with a second pulse repetition frequency at 12.5 pps, which meant that a reflection would have to be from further than away before it would be seen during the next reception period.

Operation began with the Type T.3026 transmitter sending a pulse of radio energy into the transmission antennas from a hut beside the towers. Each station had two T.3026's, one active and one standby. The signal filled space in front of the antenna, flooding the entire area. Due to the transmission effects of the multiple stacked antennas, the signal was most strong directly along the line of shoot, and dwindled on either side. An area about 50 degrees to either side of the line was filled with enough energy to make detection practical.

The Type T.3026 transmitter was provided by Metropolitan-Vickers, based on a design used for a BBC transmitter at Rugby. A unique feature of the design was the "demountable" valves, which could be opened for service, and had to be connected to an oil diffusion vacuum pump for continual evacuation while in use. The valves were able to operate at one of four selected frequencies between 20 and 55 MHz, and switched from one to another in 15 seconds. To produce the short pulses of signal, the transmitter consisted of Hartley oscillators feeding a pair of tetrode amplifier valves. The tetrodes were switched on and off by a pair of mercury vapour thyratrons connected to a timing circuit, the output of which biased the control and screen grids of the tetrode positively while a bias signal kept it normally turned off.

Stations were arranged so their fan-shaped broadcast patterns slightly overlapped to cover gaps between the stations. However, it was found that the timers controlling the broadcasts could drift and the broadcasts from one station would begin to be seen at others, a phenomenon known as "running rabbits". To avoid this, power from the National Grid was used to provide a convenient phase-locked 50 Hz signal that was available across the entire nation. Each CH station was equipped with a phase-shifting transformer that triggered it at a different point on the grid waveform. The output of the transformer was fed to a Dippy oscillator that produced sharp pulses at 25 Hz, phase-locked to the output from the transformer. The locking was "soft", so short-term variations in the phase or frequency of the grid were filtered out.

During times of strong ionospheric reflection, especially at night, it was possible that the receiver would see reflections from the ground after one reflection. To address this problem, the system was later provided with a second pulse repetition frequency at 12.5 pps, which meant that a reflection would have to be from further than away before it would be seen during the next reception period.

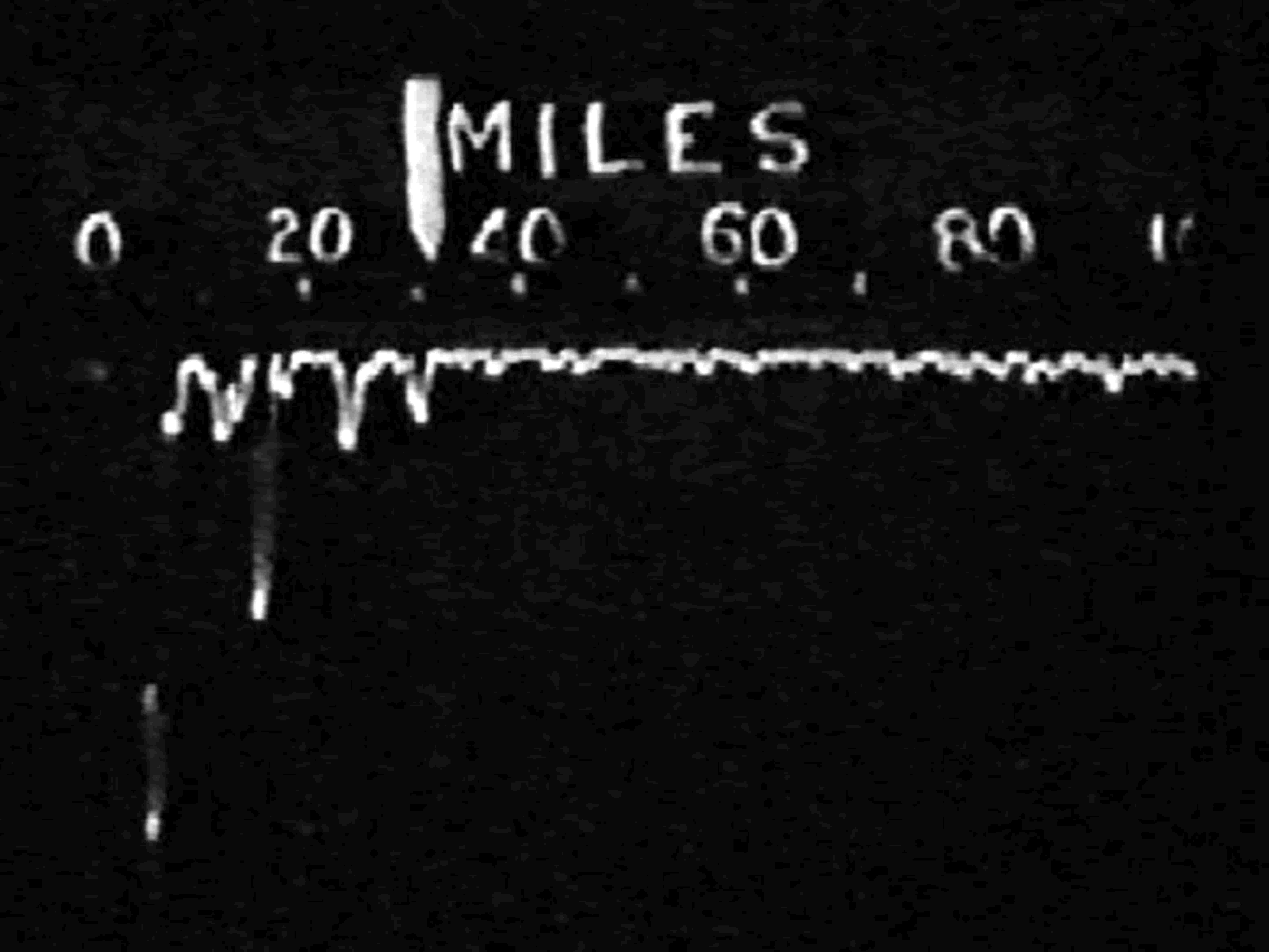

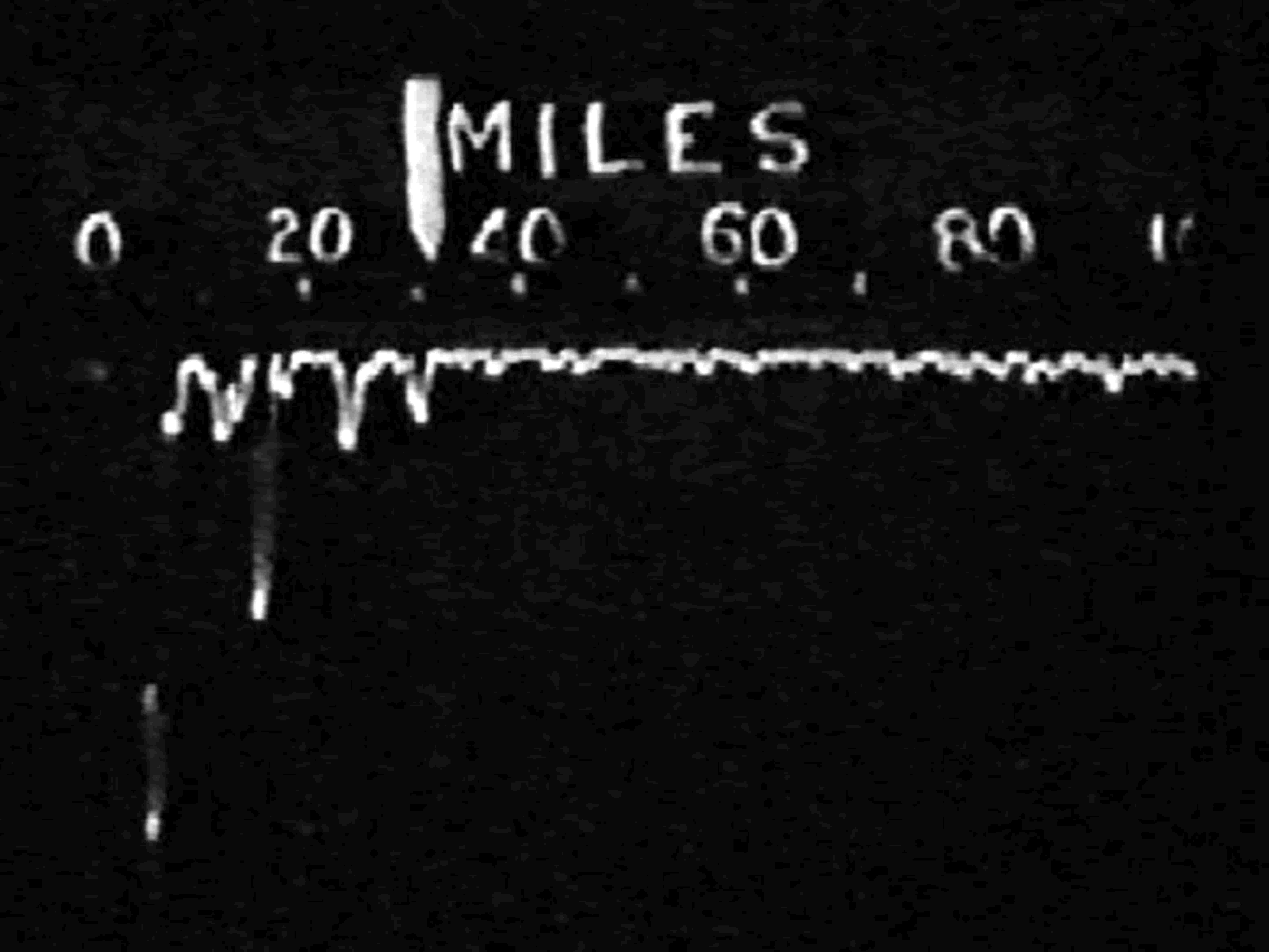

Determining the location in space of a given blip was a complex multi-step process. First the operator would select a set of receiver antennas using the motorized switch, feeding signals to the receiver system. The antennas were connected together in pairs, forming two directional antennas, sensitive primarily along the X and Y axes respectively, Y being the line of shoot. The operator would then "swing the gonio", or "hunt", back and forth until the selected blip reached its minimum deflection on this display (or maximum, at 90 degrees off). The operator would measure the distance against the scale, and then tell the plotter the range and bearing of the selected target. The operator would then select a different blip on the display and repeat the process. For targets at different altitudes, the operator might have to try different antennas to maximize the signal.

On the receipt of a set of

Determining the location in space of a given blip was a complex multi-step process. First the operator would select a set of receiver antennas using the motorized switch, feeding signals to the receiver system. The antennas were connected together in pairs, forming two directional antennas, sensitive primarily along the X and Y axes respectively, Y being the line of shoot. The operator would then "swing the gonio", or "hunt", back and forth until the selected blip reached its minimum deflection on this display (or maximum, at 90 degrees off). The operator would measure the distance against the scale, and then tell the plotter the range and bearing of the selected target. The operator would then select a different blip on the display and repeat the process. For targets at different altitudes, the operator might have to try different antennas to maximize the signal.

On the receipt of a set of

Early Radar Memories

Memories of Sgt. Jean Semple, one of Britain's pioneer radar operators

RAF Bawdsey Chain Home Radar Station

at Subterranean Britain

RAF Radar Museum

Life at Darsham

– BBC

Great Baddow Chain Home Mast & Radar Anniversary

Chain Home Radar – A Personal Reminiscence

M Scanlan, ''GEC Review'', 1993

Early radar development in the UK

at purbeckradar.co.uk

60 (Signals) Group, Fighter Command

(pdf) {{Subject bar , portal1=United Kingdom , portal2=Transport World War II sites in the United Kingdom Battle of Britain Ground radars World War II British electronics World War II radars Military radars of the United Kingdom Air defence radar networks Military equipment introduced in the 1930s 1938 establishments in the United Kingdom

early warning

An early warning system is a warning system that can be implemented as a Poset, chain of information communication systems and comprises sensors, Detection theory, event detection and decision support system, decision subsystems for early identi ...

radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

stations built by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the official name Air Ministry Experimental Station Type 1 ( AMES Type 1) in 1940, the radar units were also known as Chain Home for most of their life. Chain Home was the first early warning radar network in the world and the first military radar system to reach operational status. Its effect on the war made it one of the most powerful systems of what became known as the "Wizard War".

In late 1934, the Tizard Committee asked radio expert Robert Watson-Watt to comment on the repeated claims of radio death rays and reports suggesting Germany had built some sort of radio weapon. His assistant, Arnold Wilkins, demonstrated that a death ray was impossible but suggested radio could be used for long-range detection. In February 1935, a successful demonstration was arranged by placing a receiver near a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

short wave transmitter and flying an aircraft around the area. Using commercial short wave radio hardware, Watt's team built a prototype pulsed transmitter and by June 1935 it detected an aircraft that happened to be flying past. Basic development was completed by the end of the year, with detection ranges on the order of .

In 1936 attention was focused on a production version, and early 1937 saw the addition of height finding. The first five stations, covering the approaches to London, were installed by 1937 and began full-time operation in 1938. Over the next two years, additional stations were built while the problem of disseminating the information to the fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft (early on also ''pursuit aircraft'') are military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air supremacy, air superiority of the battlespace. Domina ...

led to the first integrated ground-controlled interception

Ground-controlled interception (GCI) is an air defence tactic whereby one or more radar stations or other observational stations are linked to a command communications centre which guides interceptor aircraft to an airborne target. This tactic wa ...

network, the Dowding system. By the time the war started, most of the east and south coasts had radar coverage.

Chain Home proved important during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

in 1940. CH systems could detect enemy aircraft while they were forming over France, giving RAF commanders ample time to marshal their aircraft in the path of the raid. This had the effect of multiplying the effectiveness of the RAF to the point that it was as if they had three times as many fighters, allowing them to defeat frequently larger German forces. The Chain Home network was continually expanded, with over 40 stations operational by the war's end, including mobile versions for use overseas. Late in the war, when the threat of ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' bombing had ended, the CH systems were used to detect V2 missile launches. UK radar systems were wound down after the war but the start of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

led to the Chain Home radars being pressed into service in the new ROTOR system until replaced by newer systems in the 1950s. Only a few of the original sites remain.

Development

Prior experiments

From the earliest days ofradio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

technology, signals had been used for navigation using the radio direction finding (RDF) technique. RDF can determine the bearing to a radio transmitter, and several such measurements can be combined to produce a radio fix

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

, allowing the receiver's position to be calculated. Given some basic changes to the broadcast signal, it was possible for the receiver to determine its location using a single station. The UK pioneered one such service in the form of the Orfordness Beacon

The Orfordness Rotating Wireless Beacon, known simply as the Orfordness Beacon or sometimes the Black Beacon, was an early radio navigation system introduced by the United Kingdom in July 1929. It allowed the angle to the station to be measured ...

.

Through the early period of radio development it was widely known that certain materials, especially metal, reflected radio signals. This led to the possibility of determining the location of objects by broadcasting a signal and then using RDF to measure the bearing of any reflections. Such a system saw patents issued to Germany's Christian Hülsmeyer in 1904, and widespread experimentation with the basic concept was carried out from then on. These systems revealed only the bearing to the target, not the range, and due to the low power of radio equipment of that era, they were useful only for short-range detection. This led to their use for iceberg and collision warning in fog or bad weather, where all that was required was the rough bearing of nearby objects.

The use of radio detection specifically against aircraft was first considered in the early 1930s. Teams in the UK, US, Japan, Germany and others had all considered this concept and put at least some amount of effort into developing it. Lacking ranging information, such systems remained of limited use in practical terms; two angle measurements could be used, but these took time to complete using existing RDF equipment and the rapid movement of the aircraft during the measurement would make coordination difficult.

Radio research in the UK

Since 1915, Robert Watson-Watt had been working for the Met Office in a lab that was colocated at the National Physical Laboratory's (NPL) Radio Research Section (RRS) at Ditton Park in Slough. Watt became interested in using the fleeting radio signals given off by

Since 1915, Robert Watson-Watt had been working for the Met Office in a lab that was colocated at the National Physical Laboratory's (NPL) Radio Research Section (RRS) at Ditton Park in Slough. Watt became interested in using the fleeting radio signals given off by lightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

as a way to track thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustics, acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorm ...

s, but existing RDF techniques were too slow to allow the direction to be determined before the signal disappeared. In 1922, he solved this by connecting a cathode-ray tube

A cathode-ray tube (CRT) is a vacuum tube containing one or more electron guns, which emit electron beams that are manipulated to display images on a phosphorescent screen. The images may represent electrical waveforms on an oscilloscope, a ...

(CRT) to a directional Adcock antenna array, originally built by the RRS but now unused. The combined system, later known as huff-duff (from HF/DF, high frequency direction finding), allowed the almost instantaneous determination of the bearing of a signal. The Met Office began using it to produce storm warnings for aviators.

During this period, Edward Appleton of King's College, Cambridge was carrying out experiments that would lead to him winning the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

. Using a BBC transmitter set up in 1923 in Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

and listening for its signal with a receiver at Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, he was able to use changes in wavelength to measure the distance to a reflective layer in the atmosphere then known as the Heaviside layer. After the initial experiments at Oxford, an NPL transmitter at Teddington

Teddington is an affluent suburb of London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Historically an Civil parish#ancient parishes, ancient parish in the county of Middlesex and situated close to the border with Surrey, the district became ...

was used as a source, received by Appleton in an out-station of King's College in the East End of London. Watt learned of these experiments and began conducting the same measurements using his team's receivers in Slough. From then on, the two teams interacted regularly and Watt coined the term ionosphere

The ionosphere () is the ionized part of the upper atmosphere of Earth, from about to above sea level, a region that includes the thermosphere and parts of the mesosphere and exosphere. The ionosphere is ionized by solar radiation. It plays ...

to describe the multiple atmospheric layers they discovered.

In 1927 the two radio labs, at the Met Office and NPL, were combined to form the Radio Research Station (with the same acronym, RRS), run by the NPL with Watt as the Superintendent. This provided Watt with direct contact to the research community, as well as the chief signals officers of the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. Watt became a well-known expert in the field of radio technology. This began a long period where Watt agitated for the NPL to take a more active role in technology development, as opposed to its pure research role. Watt was particularly interested in the use of radio for long-range aircraft navigation, but the NPL management at Teddington was not receptive and these proposals went nowhere.

Detection of aircraft

In 1931, Arnold Frederic Wilkins joined Watt's staff in Slough. As the "new boy", he was given a variety of menial tasks to complete. One of these was to select a new shortwave receiver for ionospheric studies, a task he undertook with great seriousness. After reading everything available on several units, he selected a model from the General Post Office (GPO) that worked at (for that time) very high frequencies. As part of their tests of this system, in June 1932 the GPO published a report, No. 232 ''Interference by Aeroplanes''. The report recounted the GPO testing team's observation that aircraft flying near the receiver caused the signal to change in intensity, an annoying effect known as fading. The stage was now set for the development of radar in the UK. Using Wilkins' knowledge that shortwave signals bounced off aircraft, a BBC transmitter to light up the sky as in Appleton's experiment, and Watt's RDF technique to measure angles, a complete radar could be built. While such a system could determine the angle to a target, it could not determine its range and provide a location in space. To do so, two such measurements would have to be made from different locations. Watt's huff-duff technique solved the problem of making rapid measurements, but the issue of coordinating the measurement at two stations remained, as did any inaccuracies in measurement or differences in calibration between the two stations. The missing technique that made radar practical was the use of pulses to determine range by measuring the time between the transmission of the signal and reception of the reflected signal. This would allow a single station to measure angle and range simultaneously. In 1924, two researchers at the Naval Research Laboratory in the United States, Merle Tuve and Gregory Briet, decided to recreate Appleton's experiment using timed pulsed signals instead of the changing wavelengths. The application of this technique to a detection system was not lost on those working in the field, and such a system was prototyped by W. A. S. Butement and P. E. Pollard of the British Signals Experimental Establishment (SEE) in 1931. TheWar Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

proved uninterested in the concept and the development remained little known outside SEE.

"The bomber will always get through"

At the same time, the need for such a system was becoming increasingly pressing. In 1932,

At the same time, the need for such a system was becoming increasingly pressing. In 1932, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

and his friend, confidant and scientific advisor Frederick Lindemann travelled by car in Europe, where they saw the rapid rebuilding of the German aircraft industry. It was in November of that year that Stanley Baldwin gave his famous speech, stating that " The bomber will always get through".

In the early summer of 1934, the RAF carried out large-scale exercises with up to 350 aircraft. The forces were split, with bombers attempting to attack London, while fighters, guided by the Observer Corps, attempted to stop them. The results were dismal. In most cases, the vast majority of the bombers reached their target without ever seeing a fighter. To address the one-sided results, the RAF gave increasingly accurate information to the defenders, eventually telling the observers where and when the attacks would be taking place. Even then, 70 per cent of the bombers reached their targets unhindered. The numbers suggested any targets in the city would be destroyed. Squadron Leader P. R. Burchall summed up the results by noting that "a feeling of defencelessness and dismay, or at all events of uneasiness, has seized the public." In November, Churchill gave a speech on "The threat of Nazi Germany" in which he pointed out that the Royal Navy could not protect Britain from an enemy who attacked by air.

Through the early 1930s, a debate raged within British military and political circles about strategic airpower. Baldwin's famous speech led many to believe the only way to prevent the bombing of British cities was to make a strategic bomber force so large it could, as Baldwin put it, "kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy.". Even the highest levels of the RAF came to agree with this policy, publicly stating that their tests suggested that "'The best form of defence is attack' may be all-too-familiar platitudes, but they illustrate the only sound method of defending this country from air invasion. It is attack that counts." As it became clear the Germans were rapidly rearming the ''Luftwaffe'', the fear grew RAF could not meet the objective of winning such a tit-for-tat exchange and many suggested they invest in a massive bomber building exercise.

Others felt advances in fighters meant the bomber was increasingly vulnerable and suggested at least exploring a defensive approach. Among the latter group was Lindemann, test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testin ...

and scientist, who noted in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' in August 1934 that "To adopt a defeatist attitude in the face of such a threat is inexcusable until it has definitely been shown that all the resources of science and invention have been exhausted."

Tales of destructive "rays"

In 1923–24 inventor Harry Grindell Matthews repeatedly claimed to have built a device that projected energy over long ranges and attempted to sell it to the War Office, but it was deemed to be fraudulent. His attempts spurred on many other inventors to contact the British military with claims of having perfected some form of the fabled electric or radio " death ray". Some turned out to be frauds and none turned out to be feasible.

Around the same time, a series of stories suggested another radio weapon was being developed in Germany. The stories varied, with one common thread being a death ray, and another that used the signals to interfere with an engine's

In 1923–24 inventor Harry Grindell Matthews repeatedly claimed to have built a device that projected energy over long ranges and attempted to sell it to the War Office, but it was deemed to be fraudulent. His attempts spurred on many other inventors to contact the British military with claims of having perfected some form of the fabled electric or radio " death ray". Some turned out to be frauds and none turned out to be feasible.

Around the same time, a series of stories suggested another radio weapon was being developed in Germany. The stories varied, with one common thread being a death ray, and another that used the signals to interfere with an engine's ignition system

Ignition systems are used by heat engines to initiate combustion by igniting the fuel-air mixture. In a spark ignition versions of the internal combustion engine (such as petrol engines), the ignition system creates a spark to ignite the fuel-ai ...

to cause the engine to stall. One commonly repeated story involved an English couple who were driving in the Black Forest

The Black Forest ( ) is a large forested mountain range in the States of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is th ...

on holiday and had their car fail in the countryside. They claimed they were approached by soldiers who told them to wait while they conducted a test, and were then able to start their engine without trouble when the test was complete. This was followed shortly thereafter by a story in a German newspaper with an image of a large radio antenna that had been installed on Feldberg in the same area.

Although highly skeptical about claims of engine-stopping rays and death rays, the Air Ministry could not ignore them as they were theoretically possible. If such systems could be built, it might render bombers useless. If this were to happen, the night bomber deterrent might evaporate overnight, leaving the UK open to attack by Germany's ever-growing air fleet. Conversely, if the UK had such a device, the population could be protected.

In 1934, along with a movement to establish a scientific committee to examine these new types of weapons, the RAF offered a £1,000 prize to anyone who could demonstrate a working model of a death ray that could kill a sheep at 100 yards; it went unclaimed.

Tizard committee

The need to research better forms of air defense prompted Harry Wimperis to press for the formation of a study group to consider new concepts. Lord Londonderry, then Secretary of State for Air, approved the formation of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence in November 1934, askingHenry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

to chair the group, which thus became better known to history as the Tizard Committee.

When Wimperis sought an expert in radio to help judge the death-ray concept, he was naturally directed to Watt. He wrote to Watt "on the practicability of proposals of the type colloquially called 'death ray'". The two met on 18 January 1935, and Watt promised to look into the matter. Watt turned to Wilkins for help but wanted to keep the underlying question a secret. He asked Wilkins to calculate what sort of radio energy would be needed to raise the temperature of of water at a distance of from . To Watt's bemusement, Wilkins immediately surmised this was a question about a death ray. He made a number of back-of-the-envelope calculations demonstrating the amount of energy needed would be impossible given the state of the art in electronics.

According to R. V. Jones, when Wilkins reported the negative results, Watt asked, "Well then, if the death ray is not possible, how can we help them?" Wilkins recalled the earlier report from the GPO, and noted that the wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the opposite wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingsp ...

of a contemporary bomber aircraft, about , would be just right to form a half-wavelength dipole antenna for signals in the range of 50 m wavelength, or about 6 MHz. In theory, this would efficiently reflect the signal and could be picked up by a receiver to give an early indication of approaching aircraft.

"Less unpromising"

Watt wrote back to the committee saying the death ray was extremely unlikely, but added:

The letter was discussed at the first official meeting of the Tizard Committee on 28 January 1935. The utility of the concept was evident to all attending, but the question remained whether it was actually possible. Albert Rowe and Wimperis both checked the maths and it appeared to be correct. They immediately wrote back asking for a more detailed consideration. Watt and Wilkins followed up with a 14 February secret memo entitled ''Detection and Location of Aircraft by Radio Means''. In the new memo, Watson-Watt and Wilkins first considered various natural emanations from the aircraft – light, heat and radio waves from the engine ignition system – and demonstrated that these were too easy for the enemy to mask to a level that would be undetectable at reasonable ranges. They concluded that radio waves from their own transmitter would be needed.

Wilkins gave specific calculations for the expected reflectivity of an aircraft. The received signal would be only 10−19 times as strong as the transmitted one, but such sensitivity was considered to be within the state of the art. To reach this goal, a further improvement in receiver sensitivity of two times was assumed. Their ionospheric systems broadcast only about 1 kW, but commercial shortwave systems were available with 15 amp transmitters (about 10 kW) that they calculated would produce a signal detectable at about . They went on to suggest that the output power could be increased as much as ten times if the system operated in pulses instead of continuously, and that such a system would have the advantage of allowing range to the targets to be determined by measuring the time delay between transmission and reception on an

Watt wrote back to the committee saying the death ray was extremely unlikely, but added:

The letter was discussed at the first official meeting of the Tizard Committee on 28 January 1935. The utility of the concept was evident to all attending, but the question remained whether it was actually possible. Albert Rowe and Wimperis both checked the maths and it appeared to be correct. They immediately wrote back asking for a more detailed consideration. Watt and Wilkins followed up with a 14 February secret memo entitled ''Detection and Location of Aircraft by Radio Means''. In the new memo, Watson-Watt and Wilkins first considered various natural emanations from the aircraft – light, heat and radio waves from the engine ignition system – and demonstrated that these were too easy for the enemy to mask to a level that would be undetectable at reasonable ranges. They concluded that radio waves from their own transmitter would be needed.

Wilkins gave specific calculations for the expected reflectivity of an aircraft. The received signal would be only 10−19 times as strong as the transmitted one, but such sensitivity was considered to be within the state of the art. To reach this goal, a further improvement in receiver sensitivity of two times was assumed. Their ionospheric systems broadcast only about 1 kW, but commercial shortwave systems were available with 15 amp transmitters (about 10 kW) that they calculated would produce a signal detectable at about . They went on to suggest that the output power could be increased as much as ten times if the system operated in pulses instead of continuously, and that such a system would have the advantage of allowing range to the targets to be determined by measuring the time delay between transmission and reception on an oscilloscope

An oscilloscope (formerly known as an oscillograph, informally scope or O-scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying voltages of one or more signals as a function of time. Their main purpose is capturing i ...

. The rest of the required performance would be made up by increasing the gain of the antennas by making them very tall, focusing the signal vertically. The memo concluded with an outline for a complete station using these techniques. The design was almost identical to the CH stations that went into service.

Daventry experiment

The letter was seized on by the Committee, who immediately released £4,000 to begin development. They petitioned Hugh Dowding, the Air Member for Supply and Research, to ask the Treasury for another £10,000. Dowding was extremely impressed with the concept, but demanded a practical demonstration before further funding was released.

Wilkins suggested using the new 10 kW, 49.8 m

The letter was seized on by the Committee, who immediately released £4,000 to begin development. They petitioned Hugh Dowding, the Air Member for Supply and Research, to ask the Treasury for another £10,000. Dowding was extremely impressed with the concept, but demanded a practical demonstration before further funding was released.

Wilkins suggested using the new 10 kW, 49.8 m BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

Borough Hill shortwave station in Daventry

Daventry ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the West Northamptonshire unitary authority area of Northamptonshire, England, close to the border with Warwickshire. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, Daventry had a populati ...

, Northamptonshire as a suitable ''ad hoc'' transmitter. The receiver and an oscilloscope were placed in a delivery van the RRS used for measuring radio reception around the countryside. On 26 February 1935, they parked the van in a field near Upper Stowe and connected it to wire antennas stretched across the field on top of wooden poles. A Handley Page Heyford made four passes over the area, producing clearly notable effects on the CRT display on three of the passes. A memorial stone was placed at the site of the test.

Observing the test were Watt, Wilkins, and several other members of the RRS team, along with Rowe representing the Tizard Committee. Watt was so impressed he later claimed to have exclaimed: "Britain has become an island again!"

Rowe and Dowding were equally impressed. It was at this point that Watt's previous agitation over development became important; NPL management remained uninterested in practical development of the concept, and was happy to allow the Air Ministry to take over the team. Days later, the Treasury released £12,300 for further development, and a small team of the RRS researchers were sworn to secrecy and began developing the concept. A system was to be built at the RRS station, and then moved to Orfordness for over-water testing. Wilkins would develop the receiver based on the GPO units, along with suitable antenna systems. This left the problem of developing a suitable pulsed transmitter. An engineer familiar with these concepts was needed.

Experimental system

Edward George Bowen joined the team after responding to a newspaper advertisement looking for a radio expert. Bowen had previously worked on ionosphere studies under Appleton, and was well acquainted with the basic concepts. He had also used the RRS' RDF systems at Appleton's request and was known to the RRS staff. After a breezy interview, Watson-Watt and Jock Herd stated the job was his if he could sing the Welsh national anthem. He agreed, but only if they would sing the Scottish one in return. They declined, and gave him the job. Starting with the BBC transmitter electronics, but using a new transmitter valve from the Navy, Bowen produced a system that transmitted a 25 kW signal at 6 MHz (50 metre wavelength), sending out 25 μs long pulses 25 times a second. Meanwhile, Wilkins and L.H. Bainbridge-Bell built a receiver based on electronics from Ferranti and one of the RRS CRTs. They decided not to assemble the system at the RRS for secrecy reasons. The team, now consisting of three scientific officers and six assistants, began moving the equipment to Orfordness on 13 May 1935. The receiver and transmitter were set up in old huts left over fromWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

artillery experiments, the transmitter antenna was a single dipole

In physics, a dipole () is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs in two ways:

* An electric dipole moment, electric dipole deals with the separation of the positive and negative electric charges found in any electromagnetic system. A simple ...

strung horizontally between two poles, and the receiver a similar arrangement of two crossed wires.

The system showed little success against aircraft, although echoes from the ionosphere as far as 1,000 miles away were noted. The group released several reports on these effects as a cover story, claiming that their ionospheric studies had been interfering with the other experiments at the RRS at Slough, and expressing their gratitude that the Air Ministry had granted them access to unused land at Orfordness to continue their efforts. Bowen continued increasing the voltage in the transmitter, starting with the 5000 volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, Voltage#Galvani potential vs. electrochemical potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units, International System of Uni ...

maximum suggested by the Navy, but increasing in steps over several months to 12,000 V, which produced pulses of 200 kW. Arcing between the valves required the transmitter to be rebuilt with more room between them, while arcing on the antenna was solved by hanging copper balls from the dipole to reduce corona discharge.

By June the system was working well, although Bainbridge-Bell proved to be so skeptical of success that Watt eventually returned him to the RRS and replaced him with Nick Carter. The Tizard Committee visited the site on 15 June to examine the team's progress. Watt secretly arranged for a Vickers Valentia to fly nearby, and years later insisted that he saw the echoes on the display, but no one else recalls seeing these.

Watt decided not to return to the RRS with the rest of the Tizard group and stayed with the team for another day. With no changes made to the equipment, on 17 June the system was turned on and immediately provided returns from an object at . After tracking it for some time, they watched it fly off to the south and disappear. Watt phoned the nearby Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town and civil parish in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, containe ...

and the superintendent stated that a Supermarine Scapa flying boat had just landed. Watt requested the aircraft return to make more passes. This event is considered the official birth date of radar in the UK.

Aircraft from RAF Martlesham Heath took over the job of providing targets for the system, and the range was continually pushed out. During a 24 July test, the receiver detected a target at and the signal was strong enough that they could determine the target was actually three aircraft in close formation. By September the range was consistently 40 miles, increasing to by the end of the year, and with the power improvements Bowen worked into the transmitter, was over by early 1936.

Planning the chain

In August 1935, Albert Rowe, secretary of the Tizard Committee, coined the term "Radio Direction and Finding" (RDF), deliberately choosing a name that could be confused with "Radio Direction Finding", a term already in widespread use.

In a 9 September 1935 memo, Watson-Watt outlined the progress to date. At that time the range was about , so Watson-Watt suggested building a complete network of stations apart along the entire east coast. Since the transmitters and receivers were separate, to save development costs he suggested placing a transmitter at every other station. The transmitter signal could be used by a receiver at that site as well as the ones on each side of it. This was quickly rendered moot by the rapid increases in range. When the Committee next visited the site in October, the range was up to , and Wilkins was working on a method for height finding using multiple antennas.

In spite of its ''ad hoc'' nature and short development time of less than six months, the Orfordness system had already become a useful and practical system. In comparison, the acoustic mirror systems that had been in development for a decade were still limited to only range under most conditions, and were very difficult to use in practice. Work on mirror systems ended, and on 19 December 1935, a £60,000 contract for five RDF stations along the south-east coast was sent out, to be operational by August 1936.

The only person not convinced of the utility of RDF was Lindemann. He had been placed on the Committee at the insistence of his friend, Churchill, and proved unimpressed with the team's work. When he visited the site, he was upset by the crude conditions, and apparently, by the box lunch he had to eat. Lindemann strongly advocated the use of

In August 1935, Albert Rowe, secretary of the Tizard Committee, coined the term "Radio Direction and Finding" (RDF), deliberately choosing a name that could be confused with "Radio Direction Finding", a term already in widespread use.

In a 9 September 1935 memo, Watson-Watt outlined the progress to date. At that time the range was about , so Watson-Watt suggested building a complete network of stations apart along the entire east coast. Since the transmitters and receivers were separate, to save development costs he suggested placing a transmitter at every other station. The transmitter signal could be used by a receiver at that site as well as the ones on each side of it. This was quickly rendered moot by the rapid increases in range. When the Committee next visited the site in October, the range was up to , and Wilkins was working on a method for height finding using multiple antennas.

In spite of its ''ad hoc'' nature and short development time of less than six months, the Orfordness system had already become a useful and practical system. In comparison, the acoustic mirror systems that had been in development for a decade were still limited to only range under most conditions, and were very difficult to use in practice. Work on mirror systems ended, and on 19 December 1935, a £60,000 contract for five RDF stations along the south-east coast was sent out, to be operational by August 1936.

The only person not convinced of the utility of RDF was Lindemann. He had been placed on the Committee at the insistence of his friend, Churchill, and proved unimpressed with the team's work. When he visited the site, he was upset by the crude conditions, and apparently, by the box lunch he had to eat. Lindemann strongly advocated the use of infrared

Infrared (IR; sometimes called infrared light) is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than that of visible light but shorter than microwaves. The infrared spectral band begins with the waves that are just longer than those ...

systems for detection and tracking and numerous observers have noted Lindemann's continual interference with radar. As Bowen put it,

Churchill's backing meant the other members' complaints about his behaviour were ignored. The matter was eventually referred back to Lord Swinton, the new Secretary of State for Air. Swinton solved the problem by dissolving the original Committee and reforming it with Appleton in Lindemann's place.

As the development effort grew, Watt requested a central research station be established "of large size and with ground space for a considerable number of mast and aerial systems". Several members of the team went on scouting trips with Watt to the north of Orfordness but found nothing suitable. Then Wilkins recalled having come across an interesting site about south of Orfordness, some time earlier while on a Sunday drive. He recalled it because it was some above sea level, which was unusual in that area. The large manor house on the property would have ample room for experimental labs and offices. In February and March 1936, the team moved to Bawdsey Manor and established the Air Ministry Experimental Station (AMES). When the scientific team left in 1939, the site became the operational CH site RAF Bawdsey.

While the "ness team" began moving to Bawdsey, the Orfordness site remained in use. This proved useful during one demonstration when the new system recently completed at Bawdsey failed. The next day, Robert Hanbury-Brown and the new recruit Gerald Touch started up the Orfordness system and were able to run the demonstrations from there. The Orfordness site was not closed until 1937.

Into production

The system was deliberately developed using existing commercially available technology to speed introduction. The development team could not afford the time to develop and debug new technology. Watt, a pragmatic engineer, believed "third-best" would do if "second-best" would not be available in time and "best" never available at all. This led to the use of the 50 m wavelength (around 6 MHz), which Wilkins suggested would resonate in a bomber's wings and improve the signal. Unfortunately, this also meant that the system was increasingly blanketed by noise as new commercial broadcasts began taking up this formerly high-frequency spectrum. The team responded by reducing their own wavelength to 26 m (around 11 MHz) to get clear spectrum. To everyone's delight, and contrary to Wilkins' 1935 calculations, the shorter wavelength produced no loss of performance. This led to a further reduction to 13 m, and finally the ability to tune between 10 and 13 m, (roughly 30-20 MHz) to provide some frequency agility to help avoid jamming.

Wilkins' method of height-finding was added in 1937. He had originally developed this system as a way to measure the vertical angle of transatlantic broadcasts while working at the RRS. The system consisted of several parallel dipoles separated vertically on the receiver masts. Normally the RDF goniometer was connected to two crossed dipoles at the same height and used to determine the bearing to a target return. For height finding, the operator instead connected two antennas at different heights and carried out the same basic operation to determine the vertical angle. Because the transmitter antenna was deliberately focused vertically to improve gain, a single pair of such antennas would only cover a thin vertical angle. A series of such antennas was used, each pair with a different centre angle, providing continuous coverage from about 2.5 degrees over the horizon to as much as 40 degrees above it. With this addition, the final remaining piece of Watt's original memo was accomplished and the system was ready to go into production.

Industry partners were canvassed in early 1937, and a production network was organized covering many companies.

The system was deliberately developed using existing commercially available technology to speed introduction. The development team could not afford the time to develop and debug new technology. Watt, a pragmatic engineer, believed "third-best" would do if "second-best" would not be available in time and "best" never available at all. This led to the use of the 50 m wavelength (around 6 MHz), which Wilkins suggested would resonate in a bomber's wings and improve the signal. Unfortunately, this also meant that the system was increasingly blanketed by noise as new commercial broadcasts began taking up this formerly high-frequency spectrum. The team responded by reducing their own wavelength to 26 m (around 11 MHz) to get clear spectrum. To everyone's delight, and contrary to Wilkins' 1935 calculations, the shorter wavelength produced no loss of performance. This led to a further reduction to 13 m, and finally the ability to tune between 10 and 13 m, (roughly 30-20 MHz) to provide some frequency agility to help avoid jamming.

Wilkins' method of height-finding was added in 1937. He had originally developed this system as a way to measure the vertical angle of transatlantic broadcasts while working at the RRS. The system consisted of several parallel dipoles separated vertically on the receiver masts. Normally the RDF goniometer was connected to two crossed dipoles at the same height and used to determine the bearing to a target return. For height finding, the operator instead connected two antennas at different heights and carried out the same basic operation to determine the vertical angle. Because the transmitter antenna was deliberately focused vertically to improve gain, a single pair of such antennas would only cover a thin vertical angle. A series of such antennas was used, each pair with a different centre angle, providing continuous coverage from about 2.5 degrees over the horizon to as much as 40 degrees above it. With this addition, the final remaining piece of Watt's original memo was accomplished and the system was ready to go into production.

Industry partners were canvassed in early 1937, and a production network was organized covering many companies. Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

took over design and production of the transmitters, AC Cossor did the same for the receivers, the Radio Transmission Equipment Company worked on the goniometers, and the antennas were designed by a joint AMES-GPO group. The Treasury gave approval for full-scale deployment in August, and the first production contracts were sent out for 20 sets in November, at a total cost of £380,000. Installation of 15 of these sets was carried out in 1937 and 1938. In June 1938 a London headquarters was established to organize the rapidly growing force. This became the Directorate of Communications Development (DCD), with Watt named as the director. Wilkins followed him to the DCD, and A. P. Rowe took over AMES at Bawdsey. In August 1938, the first five stations were declared operational and entered service during the Munich crisis, starting full-time operation in September.

Deployment

During the summer of 1936, experiments were carried out at RAF Biggin Hill to examine what effect the presence of radar would have on an air battle. Assuming RDF would provide them 15 minutes' warning, they developed interception techniques putting fighters in front of the bombers with increasing efficiency. They found the main problems were finding their own aircraft's location, and ensuring the fighters were at the right altitude.

In a similar test against the operational radar at Bawdsey in 1937, the results were comical. As Dowding watched the ground controllers scramble to direct their fighters, he could hear the bombers passing overhead. He identified the problem not as a technological one, but in the reporting. The pilots were being sent too many reports, often contradictory. This realization led to the development of the Dowding system, an extensive network of telephone lines reporting to a central "filter room" in London where the reports from the radar stations were collected and collated, and fed back to the pilots in a clear format. The system as a whole was enormously manpower intensive.

By the outbreak of war in September 1939, there were 21 operational Chain Home stations. After the

During the summer of 1936, experiments were carried out at RAF Biggin Hill to examine what effect the presence of radar would have on an air battle. Assuming RDF would provide them 15 minutes' warning, they developed interception techniques putting fighters in front of the bombers with increasing efficiency. They found the main problems were finding their own aircraft's location, and ensuring the fighters were at the right altitude.

In a similar test against the operational radar at Bawdsey in 1937, the results were comical. As Dowding watched the ground controllers scramble to direct their fighters, he could hear the bombers passing overhead. He identified the problem not as a technological one, but in the reporting. The pilots were being sent too many reports, often contradictory. This realization led to the development of the Dowding system, an extensive network of telephone lines reporting to a central "filter room" in London where the reports from the radar stations were collected and collated, and fed back to the pilots in a clear format. The system as a whole was enormously manpower intensive.

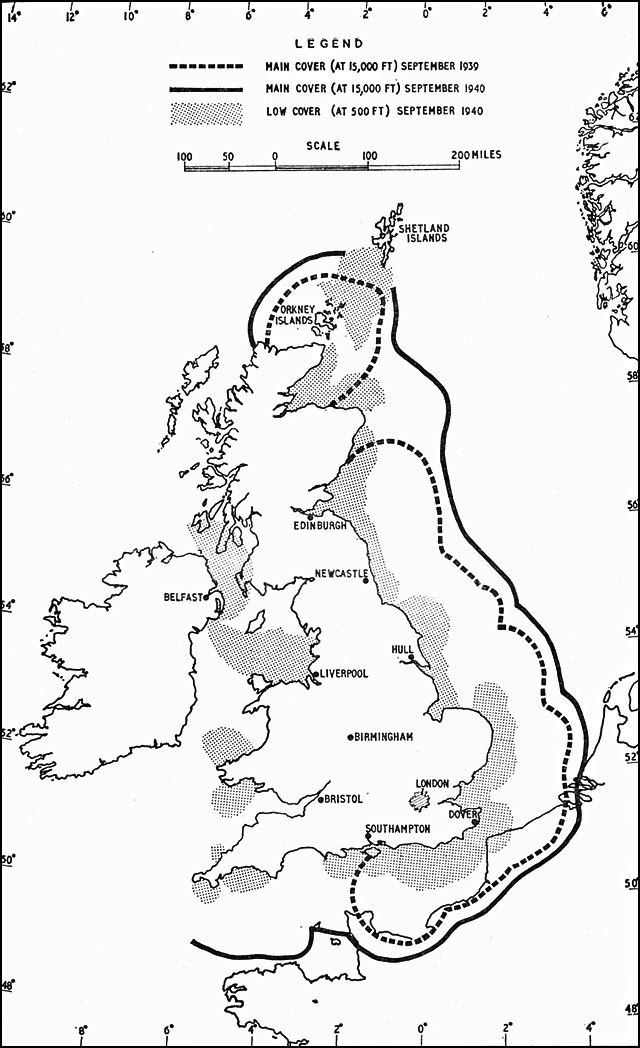

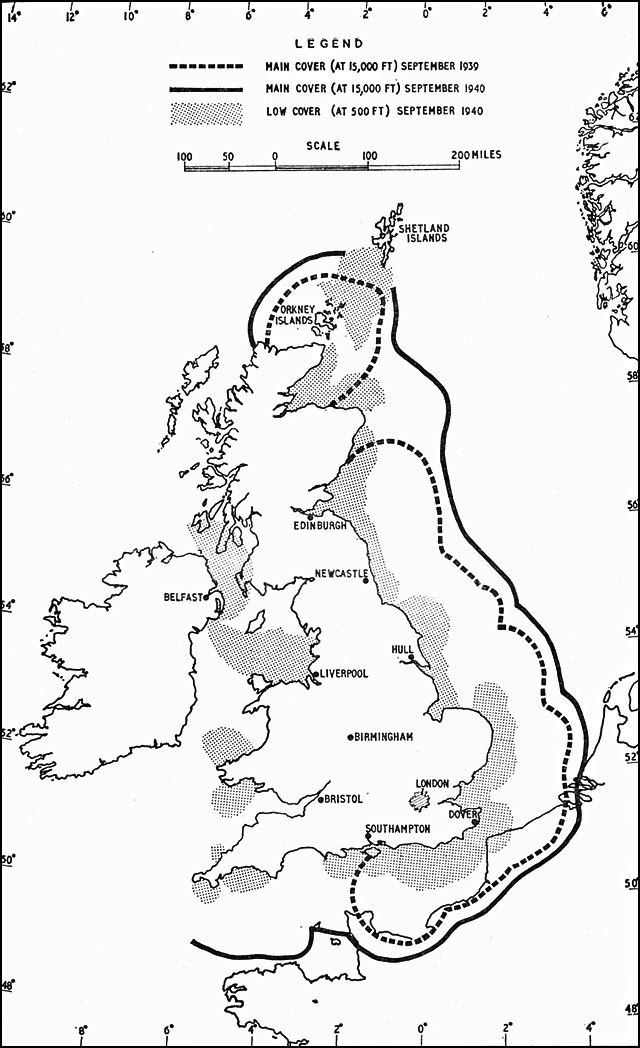

By the outbreak of war in September 1939, there were 21 operational Chain Home stations. After the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

in 1940 the network was expanded to cover the west coast and Northern Ireland. The Chain continued to be expanded throughout the war, and by 1940 it stretched from Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

in the north to Weymouth in the south. This provided radar coverage for the entire Europe-facing side of the British Isles, able to detect high-flying targets well over France. Calibration of the system was carried out initially using a flight of mostly civilian-flown, impressed Avro Rota autogyro

An autogyro (from Greek and , "self-turning"), gyroscope, gyrocopter or gyroplane, is a class of rotorcraft that uses an unpowered rotor in free autorotation to develop lift. A gyroplane "means a rotorcraft whose rotors are not engine-d ...

s flying over a known landmark, the radar then being calibrated so that the position of a target relative to the ground could be read off the CRT. The Rota was used because of its ability to maintain a relatively stationary position over the ground, the pilots learning to fly in small circles while remaining at a constant ground position, despite a headwind.

The rapid expansion of the CH network necessitated more technical and operational personnel than the UK could provide, and in 1940, a formal request was made by the British High Commission, Ottawa to the Canadian Government, appealing for men skilled in radio technology for the service of the defence of Great Britain. By the end of 1941, 1,292 trained personnel had enlisted and most were rushed to England to serve as radar mechanics.

Battle of Britain

During the battle, Chain Home stations – most notably the one at Ventnor,Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

– were attacked several times between 12 and 18 August 1940. On one occasion a section of the radar chain in Kent, including the Dover CH, was put out of action by a lucky hit on the power grid. Though the wooden huts housing the radar equipment were damaged, the towers survived owing to their open steel girder construction. Because the towers survived intact and the signals were soon restored, the ''Luftwaffe'' concluded the stations were too difficult to damage by bombing and left them alone for the remainder of the war.

Upgrades