Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, 1st Marquis of Mulhacén, (14 April 1825 – 28 or 29 January 1891) was a Spanish divisional general and geodesist. He represented Spain at the 1875 Conference of the

Jean Brunner displayed the Ibáñez-Brunner apparatus at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Copies of the Spanish standard were also made for France and Germany. These standards would be used for the most important operations of European geodesy. Indeed, the southward extension of Paris meridian's triangulation by

Jean Brunner displayed the Ibáñez-Brunner apparatus at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Copies of the Spanish standard were also made for France and Germany. These standards would be used for the most important operations of European geodesy. Indeed, the southward extension of Paris meridian's triangulation by

The 1875 Conference of the International Association of Geodesy also dealt with the best instrument to be used for the determination of

The 1875 Conference of the International Association of Geodesy also dealt with the best instrument to be used for the determination of

In 1889, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Eugène Spuller introduced the first

In 1889, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Eugène Spuller introduced the first  Nevertheless, it was an infavourable vertical deflection which gave an inaccurate determination of

Nevertheless, it was an infavourable vertical deflection which gave an inaccurate determination of

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero (1825–1891)

Universidad de Navarra. * ''Better formatted mathematics at

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de IberoReal Academia de la Historia

*Excmo

Sr. D. CARLOS IBÁÑEZ E IBÁÑEZ DE IBERO

Académicos Históricos

Real Academia de Ciecias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales

*Emilio Prieto Esteban, Rosé Ángel Robles Carbonell

El General Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, Marqués de Mulhacén

e-medida Revista Española de Metrología, June 2013. *Rafael Fraguas

Madrid, El País, February 15, 2014. *Albert Pérard

(inauguration d'un monument élevé à sa mémoire), Madrid, Institut de France Académie des Sciences – Notices et discours., 1957, 7 p., p. 26–31 *Paul Appell

LE CENTENAIRE DU GÉNÉRAL IBANEZ DE IBERO

Revue internationale de l'enseignement, Juillet-Août 1925, pp. 208–211 *Adolf Hirsch

LE GENERAL IBANEZ NOTICE NECROLOGIQUE LUE AU COMITE INTERNATIONAL DES POIDS ET MESURE, LE 12 SEPTEMBRE ET DANS LA CONFERENCE GEODESIQUE DE FLORENCE, LE 8 OCTOBRE 1891, Neuchâtel, IMPRIMERIE ATTINGER FRERES, 1891, in COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DES POIDS ET MESURES, PROCÈS-VERBAUX DES SÉANCES DE 1891, Paris, GAUTHIER-VILLARS ET FILS, IMPRIMEURS-LIBRAIRES, 1892, 197 p., pp. 3–14

o

Don Carlos IBANEZ (1825–1891), 1892, 12 p.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ibáñez, Carlos 1825 births 1891 deaths Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Spanish geodesists Elected Members of the International Statistical Institute Fellows of the Royal Statistical Society

Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

and was the first president of the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

. As a forerunner geodesist and president of the International Geodetic Association, he played a leading role in the worldwide dissemination of the metric system. His activities resulted in the distribution of a platinum and iridium prototype of the metre to all States parties to the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

during the first meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

in 1889. These prototypes defined the metre right up until 1960.

He was born in Barcelona. According to Spanish tradition, his surname was a combination of his father's first surname, Martín ''Ibáñez'' y de Prado and of his mother's first surname, Carmen ''Ibáñez de Ibero'' y González del Río. As his parents' surnames were so similar he was often referred as Ibáñez or Ibáñez de Ibero or as Marquis of Mulhacén. When he died in Nice (France), he was still enrolled in the Engineer Corps of the Spanish Army. As he died around midnight, the date of his death is ambiguous, Spaniards retained 28th, and other Europeans 29 January.

Scientific career

From the Map Commission to the Geographic and Statistical Institute in Spain

Spain adopted the metric system in 1849. The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852. The following year Ibáñez was appointed to undertake this task. As all the scientific and technical equipment for a vast undertaking of this kind had to be created, Ibáñez, in collaboration with his comrade, Captain Frutos Saavedra Meneses, drew up the project of a new apparatus for measuring bases. He recognized that the end standards with which the most perfect devices of the eighteenth century and those of the first half of the nineteenth century were still equipped, thatJean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

or Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the Sun to another star by the method ...

simply joined measuring the intervals by means of screw tabs or glass wedges, would be replaced advantageously for accuracy by the system, designed by Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler for the United States Coast Survey, and which consisted of using a single standard with lines marked on the bar and microscopic measurements. Regarding the two methods by which the effect of temperature was taken into account, Ibáñez used both the bimetallic rulers, in platinum and brass, which he first employed for the central base of Spain, and the simple iron ruler with inlaid mercury thermometers which was used in Switzerland.

Ibáñez and Saavedra went to Paris to supervise the production by Jean Brunner of a measuring instrument calibrated against the metre which they had devised and which they later compared with Borda's double-toise N°1 which was the main reference for measuring all geodetic bases in France and whose length was by definition 3.8980732 metres at a specified temperature. The four-metre-long Spanish measuring instrument, which became known as the Spanish Standard (French: ''Règle espagnole''), was replicated in order to be used in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. In 1863, Ibáñez and Ismail Effendi Mustafa compared the Spanish Standard with the Egyptian Standard in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

. These comparisons were essential, because of thermal expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to increase in length, area, or volume, changing its size and density, in response to an increase in temperature (usually excluding phase transitions).

Substances usually contract with decreasing temp ...

. Indeed, geodesists tried to accurately assess temperature of standards in the field in order to avoid temperature systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

.

In 1858 Spain's central geodetic base of triangulation was measured in Madridejos (Toledo) with exceptional precision for the time thanks to the Spanish Standard. Ibáñez and his colleagues wrote a monograph which was translated into French by Aimé Laussedat. The experiment, in which the results of two methods were compared, was a landmark in the controversy between French and German geodesists about the length of geodesic triangulation bases, and empirically validated the method of General Johann Jacob Bayer, founder of the International Association of Geodesy

The International Association of Geodesy (IAG) is a constituent association of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics focusing on the science which measures and describes the Figure of the Earth, Earth's shape, its rotation and gravity ...

.

From 1865 to 1868 Ibáñez added the survey of the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

with that of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. For this work, he devised a new instrument, which allowed much faster measurements. In 1869, Ibáñez brought it along to Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

where Alexander Ross Clarke

Alexander Ross Clarke Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (1828–1914) was a British geodesist, primarily remembered for his calculation of the Principal Triangulation of Britain (1858), the calculation of the Figure of the Earth (1858, 1860, ...

was making the necessary measurements to compare the Standards of length used in the World. Finally, this second version of the appliance, called the Ibáñez apparatus, was used in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

to measure the geodetic bases of Aarberg

Aarberg is a List of towns in Switzerland, historic town and a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the Seeland (administrative district), Seeland administrative district in the canton of Bern in Switzerland.

Aarberg lies from Bern abov ...

, Weinfelden

Weinfelden is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Thurgau in Switzerland. It is the capital of the district of the same name.

Weinfelden is an old town, which was known during Ancient Rome, Roma ...

and Bellinzona.

In 1870 Ibáñez founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute which he then directed until 1889. At the time it was the world's biggest geographic institute. It encompassed geodesy, general topography, leveling, cartography, statistics and the general service of weights and measures.

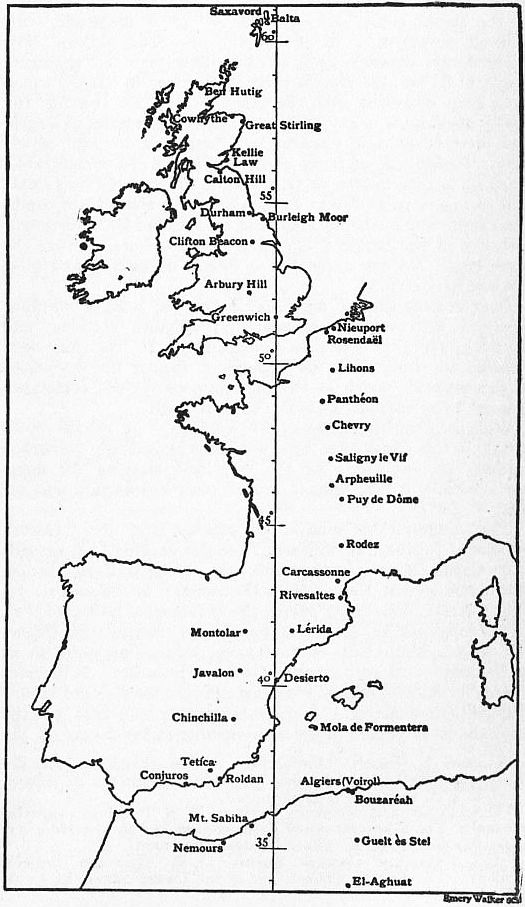

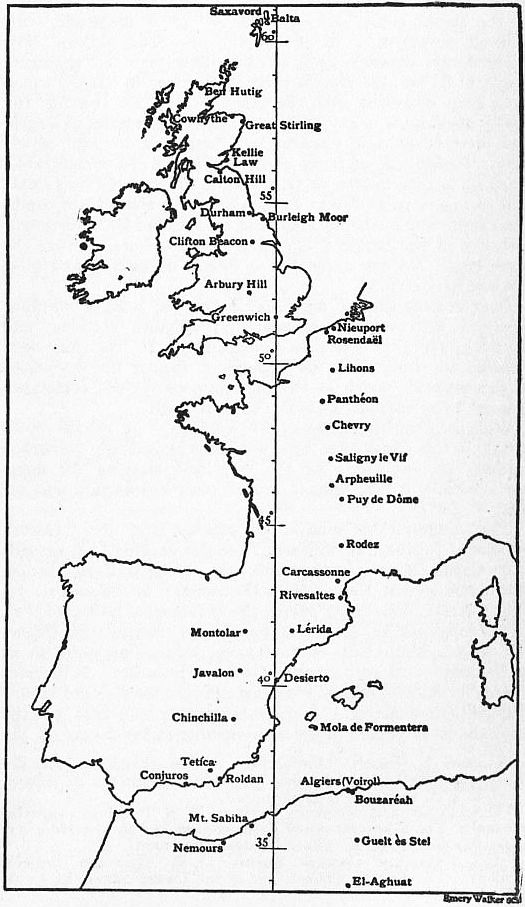

Measurement of the Paris meridian over the Mediterranean Sea

Jean Brunner displayed the Ibáñez-Brunner apparatus at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Copies of the Spanish standard were also made for France and Germany. These standards would be used for the most important operations of European geodesy. Indeed, the southward extension of Paris meridian's triangulation by

Jean Brunner displayed the Ibáñez-Brunner apparatus at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Copies of the Spanish standard were also made for France and Germany. These standards would be used for the most important operations of European geodesy. Indeed, the southward extension of Paris meridian's triangulation by Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

(1803–1804), then François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

and Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French people, French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, ma ...

(1806–1809) had not been secured by any baseline measurement in Spain.

Moreover Louis Puissant declared in 1836 to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

that Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on the ...

and Pierre Méchain had made errors in the triangulation of the meridian arc, which had been used for determining the length of the metre. This is why Antoine Yvon Villarceau verified the geodetic operations at eight points of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

arc from 1861 to 1866. Some of the errors in the operations of Delambre and Méchain were then corrected.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

and France. In 1866 at the conference of the Association of Geodesy in Neuchâtel

Neuchâtel (, ; ; ) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital (political), capital of the cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (canton), Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel ...

, Ibáñez announced that Spain would collaborate in remeasuring and extending the French meridian arc. From 1870 to 1894, François Perrier, then Jean-Antonin-Léon Bassot proceeded to a new survey. In 1879 Ibáñez and François Perrier completed the junction between the geodetic networks of Spain and Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and thus completed the measurement of a meridian arc which extended from Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

to the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

. This connection was a remarkable enterprise where triangles with a maximum length of 270 km were observed from mountain stations ( Mulhacén, Tetica, Filahoussen, M'Sabiha) over the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

This meridian arc was named West Europe-Africa Meridian-arc by Alexander Ross Clarke

Alexander Ross Clarke Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (1828–1914) was a British geodesist, primarily remembered for his calculation of the Principal Triangulation of Britain (1858), the calculation of the Figure of the Earth (1858, 1860, ...

and Friedrich Robert Helmert. It yielded a value for the equatorial radius of the earth ''a'' = 6 377 935 metres, the ellipticity being assumed as 1/299.15 according to Bessel ellipsoid. The radius of curvature of this arc is not uniform, being, in the mean, about 600 metres greater in the northern than in the southern part.

According to the calculations made at the central bureau of the International Geodetic Association, the net does not follow the meridian exactly, but deviates both to the west and to the east; actually, the meridian of Greenwich is nearer the mean than that of Paris.

International scientific collaboration in geodesy and calls for an international standard unit of length

In 1866 Spain, represented by Ibáñez, joined the Central European Arc Measurement (German: ''Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'') at the Permanent Commission meeting inNeuchâtel

Neuchâtel (, ; ; ) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital (political), capital of the cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (canton), Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel ...

. In 1867 at the second General Conference of the Central European Arc Measurement (see International Association of Geodesy

The International Association of Geodesy (IAG) is a constituent association of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics focusing on the science which measures and describes the Figure of the Earth, Earth's shape, its rotation and gravity ...

) held in Berlin, the question of an international standard unit of length was discussed to combine the measurements made in different countries to determine the size and shape of the Earth. The Conference recommended the adoption of the metre and the creation of an international metre commission, according to a preliminary discussion between Johann Jacob Baeyer, Adolphe Hirsch and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero. Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler's use of the metre in coastal survey, which had been an argument for the introduction of the Metric Act of 1866 allowing the use of the metre in the United States, probably also played a role in the choice of the metre as international scientific unit of length and the proposal by the European Arc Measurement (German: ''Europäische Gradmessung'') to "establish a European international bureau for weights and measures".

The French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

and the Bureau des Longitudes in Paris drew the attention of the French government to this issue. The Academy of St Petersburg and the English Standards Commission were in agreement with the recommendation. In November 1869 the French government issued invitations to join the International Metre Commission. Spain accepted and Ibáñez took part in the Committee of preparatory research from the first meeting of this commission in 1870. He was elected president of the Permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission in 1872. He represented Spain at the 1875 conference of the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

and at the first General Conference on Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

in 1889. At the first meeting of the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

, he was elected chairman of the committee, a position he held from 1875 to 1891. He received the Légion d'Honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

in recognition of his efforts to disseminate the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that standardization, standardizes a set of base units and a nomenclature for describing relatively large and small quantities via decimal-based multiplicative unit prefixes. Though the rules gover ...

among all nations and was awarded the Poncelet Prize for his scientific contribution to metrology.

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated, the International prototype metre would form the basis of the new international system of units, but it would no longer have any relation to the dimensions of the Earth that geodesists were trying to determine. It would be no more than the material representation of the unity of the system.

The European Arc Measurement decided the creation of an international geodetic standard at the General Conference held in Paris in 1875. Thus, the Commission resolved to acquire, at common expense, a measuring instrument which was to be used either to measure new bases in countries which did not have their own device or to repeat previous measurements. The comparisons of the new results with those provided by the old national standards would make it possible to obtain their equation. The apparatus would to be calibrated at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

(BIPM), using the prototype metre. The system with a microscope and bimetallic rulers, which had given such brilliant results in Spain, was proposed. The 1875 Conference of the International Association of Geodesy also dealt with the best instrument to be used for the determination of

The 1875 Conference of the International Association of Geodesy also dealt with the best instrument to be used for the determination of gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

. After an in-depth discussion in which an American scholar, Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

, took part, the association decided in favor of the reversion pendulum, which was used in Switzerland, and it was resolved to redo in Berlin, in the station where Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the Sun to another star by the method ...

made his famous measurements, the determination of gravity by means of devices of various kinds employed in different countries, to compare them and thus to have the equation of their scales.

The reversible pendulum built by the Repsold brothers was used in Switzerland in 1865 by Émile Plantamour for the measurement of gravitational acceleration in six stations of the Swiss geodetic network. Following the example set by this country and under the patronage of the International Geodetic Association, Austria, Bavaria, Prussia, Russia and Saxony undertook gravity determinations on their respective territories. As the figure of the Earth

In geodesy, the figure of the Earth is the size and shape used to model planet Earth. The kind of figure depends on application, including the precision needed for the model. A spherical Earth is a well-known historical approximation that is ...

could be inferred from variations of gravitational field

In physics, a gravitational field or gravitational acceleration field is a vector field used to explain the influences that a body extends into the space around itself. A gravitational field is used to explain gravitational phenomena, such as ...

, the United States Coast Survey's direction instructed Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

in the spring of 1875 to proceed to Europe for the purpose of making pendulum experiments to chief initial stations for operations of this sort, to bring the determinations of gravitational acceleration in America into communication with those of other parts of the world; and also for the purpose of making a careful study of the methods of pursuing these researches in the different countries of Europe.

President of the Permanent Commission of the European Arc Measurement from 1874 to 1886, Ibáñez became the first president of the International Geodetic Association (1887–1891) after the death of Johann Jacob Baeyer. Under Ibáñez's presidency, the International Geodetic Association acquired a global dimension with the accession of the United States, Mexico, Chile, Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and Japan.

The progresses of metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of Unit of measurement, units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to stan ...

combined with those of gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest. The study of gravity c ...

through improvement of Kater's pendulum led to a new era of geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

. If precision metrology had needed the help of geodesy, it could not continue to prosper without the help of metrology. It was then necessary to define a single unit to express all the measurements of terrestrial arcs, and all determinations of the gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

by the means of pendulum. Metrology had to create a common unit, adopted and respected by all civilized nations. Moreover, at that time, statisticians knew that scientific observations are marred by two distinct types of errors, constant errors on the one hand, and fortuitous errors, on the other hand. The effects of random errors can be mitigated by the least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

method. Constant or systematic errors on the contrary must be carefully avoided, because they arise from one or more causes which constantly act in the same way, and have the effect of always altering the result of the experiment in the same direction. They therefore deprive of any value the observations that they impinge. It was thus crucial to compare at controlled temperatures with great precision and to the same unit all the standards for measuring geodesic bases, and all the pendulum rods. Only when this series of metrological comparisons would be finished with a probable error of a thousandth of a millimetre would geodesy be able to link the works of the different nations with one another, and then proclaim the result of the measurement of the Globe. In 1901, Friedrich Robert Helmert found, mainly by gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest. The study of gravity c ...

, parameters of the ellipsoid remarkably close to reality. Although marked by the concern to correct vertical deflections, taking into account the contributions of gravimetry, research between 1910 and 1950 remained practically limited to large continental triangulations. The most significant work would be that by John Fillmore Hayford, which relied mainly on the North American national network. His ellipsoid was adopted in 1924 by the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics.

In 1889 the General Conference on Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

met at Sèvres, the seat of the International Bureau. It performed the first great deed dictated by the motto inscribed in the pediment of the splendid edifice that is the metric system: "''A tous les temps, à tous les peuples''" (For all times, to all peoples); and this deed consisted in the approval and distribution, among the governments of the states supporting the Metre Convention, of prototype standards of hitherto unknown precision intended to propagate the metric unit throughout the whole world. These prototypes were made of a platinum-iridium alloy which combined all the qualities of hardness, permanence, and resistance to chemical agents which rendered it suitable for making into standards required to last for centuries. Yet their high price excluded them from the ordinary field of science. For metrology the matter of expansibility was fundamental; as a matter of fact the temperature measuring error related to the length measurement in proportion to the expansibility of the standard and the constantly renewed efforts of metrologists to protect their measuring instruments against the interfering influence of temperature revealed clearly the importance they attached to the expansion-induced errors. It was common knowledge, for instance, that effective measurements were possible only inside a building, the rooms of which were well protected against the changes in outside temperature, and the very presence of the observer created an interference against which it was often necessary to take strict precautions. Thus, the Contracting States also received a collection of thermometers which accuracy made it possible to ensure that of length measurements.

The BIPM's thermometry work led to the discovery of special alloys of iron-nickel, in particular invar

Invar, also known generically as FeNi36 (64FeNi in the US), is a nickel–iron alloy notable for its uniquely low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE or α). The name ''Invar'' comes from the word ''invariable'', referring to its relative lac ...

, for which its director, the Swiss physicist Charles-Édouard Guillaume, was granted the Nobel Prize for physics in 1920. In 1900, the International Committee for Weights and Measures responded to a request from the International Association of geodesy and included in the work program of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures the study of measurements by invar's wires. Edvard Jäderin, a Swedish geodesist, had invented a method of measuring geodetic bases, based on the use of taut wires under a constant effort. However, before the discovery of invar, this process was much less precise than the classic method. Charles-Édouard Guillaume demonstrated the effectiveness of Jäderin's method, improved by the use of invar's threads. He measured a base in the Simplon Tunnel

The Simplon Tunnel (''Simplontunnel'', ''Traforo del Sempione'' or ''Galleria del Sempione'') is a railway tunnel on the Simplon railway that connects Brig, Switzerland, Brig, Switzerland and Domodossola, Italy, through the Alps, providing a shor ...

in 1905. The accuracy of the measurements was equal to that of the old methods, while the speed and ease of the measurements were incomparably higher.

Late career, marriages and descent

In 1889, Ibáñez had a stroke and resigned from the management of the Institute of Geography and Statistics, which he had directed for 19 years. His decision seemed to have been precipitated by the publication of a decree which took away economic control of the Institute and handed it over to the Minister of Public Works. Indeed, this resignation took effect during a smear campaign orchestrated byCarlist

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

journalist Antonio de Valbuena. The reappearance of the general's first wife after his death in 1891 further discredited him and led to the annulment of his second marriage.

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero was married in 1861 to a Frenchwoman, Jeanne Baboulène Thénié. A daughter was born from this marriage. He remarried in 1878 to a Swiss woman, Cécilia Grandchamp. Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero Grandchamp was born from this second union. After the death of Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, his two children and Cécilia Grandchamp settled in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where the latter was from.

Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero Grandchamp, engineer and doctor of philosophy and letters from the University of Paris founded in 1913 the Institute of Hispanic Studies (current Training and Research Unit of Iberian and Latin American Studies of the Faculty of Letters of Sorbonne University

Sorbonne University () is a public research university located in Paris, France. The institution's legacy reaches back to the Middle Ages in 1257 when Sorbonne College was established by Robert de Sorbon as a constituent college of the Unive ...

). Although it has been argued that the title of Marquis of Mulhacén was granted to him as a reward for the founding of the Institute of Hispanic Studies of the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, the invalidation of his parents' marriage prevented him from officially obtaining this title.

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's eldest daughter, Elena Ibáñez de Ibero, married a Swiss lawyer and politician, Jacques Louis Willemin. The title of Marquis of Mulhacén passed to their son, then to their grandson.

Legacy

General Conference on Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

with these words:

''Your task, so useful, so beneficial to mankind, has been traversed by many vicissitudes for a hundred years. Like all the great things in this world, it has cost many pains, efforts, sacrifices, not to mention the difficulties, dangers, fatigue, tribulations of all kinds, which endured the two great French astronomers Delambre and Méchain, whose works are the basis of all yours. I am sure to be your interpreter, paying them supreme tribute on this day. Who does not remember with emotion the dangers to which Méchain so generously exposed his life? General Morin, who has been your worthy colleague for so long, wrote a few lines on this subject that you will be proud to hear: "To brave dangers similar to those which Méchain ran with the necessary calm, it is not enough to be devoted to science and to its duties; you must have an empire over your senses which will protect you from this kind of vertigo, in the shelter of which the most intrepid soldiers are not always. Someone who, without flinching, has faced the bullets a hundred times is, on the contrary, surprised by this insurmountable weakness in the presence of the emptiness that space offers him." It is a soldier speaking, Gentlemen; please listen to him again when he adds: "Science therefore also has its heroes who, happier than those of war, leave behind only works useful to humanity and not ruins and vengeful hatred."''

Thanks to the determination and skill of Delambre and Méchain, the Enlightenment of science overcame the Tower of Babel of weights and measures. But it was not without difficulty: Méchain made a mistake which would almost cause him to lose his mind. In his book, ''The Measure of All Things: the seven year odyssey and hidden error that transformed the world'', Ken Alder recalls some errors that crept into the measurement of the two French scientists and that Méchain had even noticed an inaccuracy which he had not dared to admit. By measuring the latitude of two stations in Barcelona, Méchain had found that the difference between these latitudes was greater than predicted by direct measurement of distance by triangulation. Indeed, clearance in the central axis of the repeating circle caused wear and consequently the zenith

The zenith (, ) is the imaginary point on the celestial sphere directly "above" a particular location. "Above" means in the vertical direction (Vertical and horizontal, plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The z ...

measurements contained significant systematic errors.

Nevertheless, it was an infavourable vertical deflection which gave an inaccurate determination of

Nevertheless, it was an infavourable vertical deflection which gave an inaccurate determination of Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

's latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and a metre "too short" compared to a more general definition taken from the average of a large number of arcs. The geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

is not a surface of revolution and none of its meridians is identical to another, in other words, the theoretical definition of the metre was inaccessible and misleading at the time of Delambre and Mechain arc measurement, as the geoid is a ball, which on the whole can be assimilated to an ellipsoid of revolution, but which in detail differs from it so as to prohibit any generalization and any extrapolation from the measurement of a single meridian arc. Moreover, it was necessary to assume an oblateness of the Earth in order to calculate the length of the metre from the meridian arc measured by Delambre and Méchain. In 1901, Friedrich Robert Helmert determined the values of his ellipsoid of reference taking into account gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest. The study of gravity c ...

work of the International Geodetic Association. He found 1/298,3 for the flattening of the Earth. This was remarkably close to reality compared to the value of 1/344 which had been used to compute the length of the metre a century earlier.

Furthermore, until the Hayford ellipsoid was calculated, vertical deflections were considered as random errors. The distinction between systematic and random errors is far from being as sharp as one might think at first glance. In reality, there are no or very few random errors. As science progresses, the causes of certain errors are sought out, studied, their laws discovered. These errors pass from the class of random errors into that of systematic errors. The ability of the observer consists in discovering the greatest possible number of systematic errors to be able, once he has become acquainted with their laws, to free his results from them using a method or appropriate corrections. It is the experimental study of a cause of error that has led to most of the great astronomical discoveries (precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

, nutation, aberration).

Since the metre was originally defined, each time a new measurement is made, with more accurate instruments, methods or techniques, it is said that the metre is based on some error, from calculations or measurements. When Ibáñez took part to the measurement of the West Europe-Africa Meridian-arc, mathematicians like Legendre and Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; ; ; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician, astronomer, Geodesy, geodesist, and physicist, who contributed to many fields in mathematics and science. He was director of the Göttingen Observat ...

had developed new methods for processing data, including the " least squares method" which allowed to compare experimental data tainted with observational error

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are inherent in the measurement ...

s to a mathematical model. Moreover, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

would have a central role for international geodetic measurements as Charles Édouard Guillaume discovery of invar

Invar, also known generically as FeNi36 (64FeNi in the US), is a nickel–iron alloy notable for its uniquely low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE or α). The name ''Invar'' comes from the word ''invariable'', referring to its relative lac ...

minimized the impact of measurement inaccuracies due to temperature systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

. The Earth measurements thus underscored the importance of the scientific method at a time when statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

were implemented in geodesy. As a leading scientist of his time, Ibáñez was one of the 81 initial members of the International Statistical Institute (ISI) and delegate of Spain to the first ISI session (now called World Statistic Congress) in Rome in 1887.

Among the many reasons why Ibáñez could claim recognition from his country and from science, the geodetic junction of Spain and Algeria has been one of the most remarkable. Therefore, the Spanish government chose the name of the peak of Mulhacén to attach forever the memory of this famous scientific achievement to the name of Ibáñez, by conferring on him the title of 1st Marquis of Mulhacén, granted, as it is said in the royal decree, " in recognition of the brilliant services which he rendered during his long career, directing with rare talent the Geographical and Statistical Institute of Spain, and contributing to the prestige of Spain among the other nations of Europe and America ". He was indeed vice president of the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences, honorary academician of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and of the Berlin Geographical Society, of the National Academy of Sciences of Argentina, associated academician of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium, and correspondant of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

.

Unfortunately, the extension of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

arc over the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

in 1879 would soon be forgotten due to the adoption of the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrarily chosen meridian (geography), meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. On a spheroid, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian ...

of the world at the 1883 ''International Geodetic Conference'' in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, which was confirmed the next year at the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

in Washington, and because of Spain's adoption of Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being ...

by a decree of 27 July 1900, applicable from 1 January 1901. Moreover, it was the Struve Geodetic Arc which would become part of the longest meridian arc of the Old World. In 1954, the connection of the southerly extension of the Struve Arc with an arc running north from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

through Egypt would bring the course of a major meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

back to land where Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; ; – ) was an Ancient Greek polymath: a Greek mathematics, mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theory, music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of A ...

had founded geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

.

From 1910, the astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition ...

s of the Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

sent the time to sea daily through the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower from 1887 to 1889.

Locally nicknamed "''La dame de fe ...

within a radius of 5 000 km. The development of wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

allowed unifying Universal Time

Universal Time (UT or UT1) is a time standard based on Earth's rotation. While originally it was mean solar time at 0° longitude, precise measurements of the Sun are difficult. Therefore, UT1 is computed from a measure of the Earth's angle wi ...

. On 9 March 1911, France adopted Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being ...

by law. However, the law did not refer to Greenwich Prime Meridian, but to the local mean time

Local mean time (LMT) is a form of solar time that corrects the variations of local apparent time, forming a uniform time scale at a specific longitude. This measurement of time was used for everyday use during the 19th century before time zones ...

of Paris delayed by 9 minute

A minute is a unit of time defined as equal to 60 seconds.

It is not a unit in the International System of Units (SI), but is accepted for use with SI. The SI symbol for minutes is min (without a dot). The prime symbol is also sometimes used i ...

s and 21 second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

s. In 1912, following a report by Gustave Ferrié, the Bureau des Longitudes organized at the Paris Observatory a ''Conférence internationale de l'heure radiotélégraphique'' (International Radiotelegraph Time Conference). The International Time Bureau

The International Time Bureau (, abbreviated BIH), seated at the Paris Observatory, was the international bureau responsible for combining different measurements of Universal Time.

The bureau also played an important role in the research of tim ...

was created and installed in the premises of the Paris Observatory. However, due to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the International Convention was never ratified. In 1919, the existence of the International Time Bureau was formalized under the authority of an International Time Commission, under the aegis of the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

, created by Benjamin Baillaud. The International Time Bureau was dissolved in 1987 and its tasks were divided between the International Bureau of Weights and Measures and the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service

The International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), formerly the International Earth Rotation Service, is the body responsible for maintaining global time and reference frame standards, notably through its Earth Orientation P ...

(IERS).

In 1936, irregularities in the speed of Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

due to the unpredictable movement of air and water masses were discovered through the use of quartz clock

Quartz clocks and quartz watches are timepieces that use an electronic oscillator regulated by a quartz crystal to keep time. The crystal oscillator, controlled by the resonant mechanical vibrations of the quartz crystal, creates a signal with ...

s. They implied that the Earth's rotation was an imprecise way of determining time. As a result, the definition of the second, first seen as a fraction of the Earth's rotation, evolved and became a fraction of the Earth's orbit

Earth orbits the Sun at an astronomical unit, average distance of , or 8.317 light-second, light-minutes, in a retrograde and prograde motion, counterclockwise direction as viewed from above the Northern Hemisphere. One complete orbit takes & ...

. Finally, in 1967, the second was defined by atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betwee ...

s. The resulting time scale is the International Atomic Time

International Atomic Time (abbreviated TAI, from its French name ) is a high-precision atomic coordinate time standard based on the notional passage of proper time on Earth's geoid. TAI is a weighted average of the time kept by over 450 atomi ...

(TAI). Currently, it is established from more than 450 atomic clocks world-wide by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures. So far, the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service also plays a role in Coordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is the primary time standard globally used to regulate clocks and time. It establishes a reference for the current time, forming the basis for civil time and time zones. UTC facilitates international communicat ...

(UTC) by deciding whether to insert a leap second

A leap second is a one-second adjustment that is occasionally applied to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), to accommodate the difference between precise time (International Atomic Time (TAI), as measured by atomic clocks) and imprecise solar tim ...

so that it is kept in line with the rotation of the Earth.

The International System of Units

The International System of Units, internationally known by the abbreviation SI (from French ), is the modern form of the metric system and the world's most widely used system of measurement. It is the only system of measurement with official s ...

(SI, abbreviated from the French ''Système international (d'unités)''), the modern form of the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that standardization, standardizes a set of base units and a nomenclature for describing relatively large and small quantities via decimal-based multiplicative unit prefixes. Though the rules gover ...

was revised in 2019. It is the only system of measurement

A system of units of measurement, also known as a system of units or system of measurement, is a collection of units of measurement and rules relating them to each other. Systems of measurement have historically been important, regulated and defi ...

with an official status in nearly every country in the world. It comprises a coherent system of units of measurement

A unit of measurement, or unit of measure, is a definite magnitude (mathematics), magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity. Any other qua ...

starting with seven base units, which are the second (the unit of time with the symbol s), metre (length

Length is a measure of distance. In the International System of Quantities, length is a quantity with Dimension (physical quantity), dimension distance. In most systems of measurement a Base unit (measurement), base unit for length is chosen, ...

, m), kilogram (mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

, kg), ampere

The ampere ( , ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to 1 c ...

(electric current

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge c ...

, A), kelvin

The kelvin (symbol: K) is the base unit for temperature in the International System of Units (SI). The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale that starts at the lowest possible temperature (absolute zero), taken to be 0 K. By de ...

(thermodynamic temperature

Thermodynamic temperature, also known as absolute temperature, is a physical quantity which measures temperature starting from absolute zero, the point at which particles have minimal thermal motion.

Thermodynamic temperature is typically expres ...

, K), mole (amount of substance

In chemistry, the amount of substance (symbol ) in a given sample of matter is defined as a ratio () between the particle number, number of elementary entities () and the Avogadro constant (). The unit of amount of substance in the International ...

, mol), and candela

The candela (symbol: cd) is the unit of luminous intensity in the International System of Units (SI). It measures luminous power per unit solid angle emitted by a light source in a particular direction. Luminous intensity is analogous to radi ...

(luminous intensity

In photometry, luminous intensity is a measure of the wavelength-weighted power emitted by a light source in a particular direction per unit solid angle, based on the luminosity function, a standardized model of the sensitivity of the huma ...

, cd). Since 2019, the magnitudes of all SI units have been defined by declaring exact numerical values for seven ''defining constants'' when expressed in terms of their SI units. These defining constants are the hyperfine transition frequency of caesium Δ''ν''Cs, the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant exactly equal to ). It is exact because, by international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time i ...

in vacuum ''c'', the Planck constant

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, denoted by h, is a fundamental physical constant of foundational importance in quantum mechanics: a photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant, and the wavelength of a ...

''h'', the elementary charge

The elementary charge, usually denoted by , is a fundamental physical constant, defined as the electric charge carried by a single proton (+1 ''e'') or, equivalently, the magnitude of the negative electric charge carried by a single electron, ...

''e'', the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative thermal energy of particles in a ideal gas, gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin (K) and the ...

''k'', the Avogadro constant

The Avogadro constant, commonly denoted or , is an SI defining constant with an exact value of when expressed in reciprocal moles.

It defines the ratio of the number of constituent particles to the amount of substance in a sample, where th ...

''N''A, and the luminous efficacy ''K''cd.

See also

* Arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain *International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

*History of the metre

During the French Revolution, the traditional units of measure were to be replaced by consistent measures based on natural phenomena. As a base unit of length, scientists had favoured the seconds pendulum (a pendulum with a half-period of ...

* History of geodesy

References

External links

* Jaime NubiolaCarlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero (1825–1891)

Universidad de Navarra. * ''Better formatted mathematics at

Wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

.''

*

*Miguel Parrilla NietoCarlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero

*Excmo

Sr. D. CARLOS IBÁÑEZ E IBÁÑEZ DE IBERO

Académicos Históricos

Real Academia de Ciecias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales

*Emilio Prieto Esteban, Rosé Ángel Robles Carbonell

El General Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, Marqués de Mulhacén

e-medida Revista Española de Metrología, June 2013. *Rafael Fraguas

Madrid, El País, February 15, 2014. *Albert Pérard

(inauguration d'un monument élevé à sa mémoire), Madrid, Institut de France Académie des Sciences – Notices et discours., 1957, 7 p., p. 26–31 *Paul Appell

LE CENTENAIRE DU GÉNÉRAL IBANEZ DE IBERO

Revue internationale de l'enseignement, Juillet-Août 1925, pp. 208–211 *Adolf Hirsch

LE GENERAL IBANEZ NOTICE NECROLOGIQUE LUE AU COMITE INTERNATIONAL DES POIDS ET MESURE, LE 12 SEPTEMBRE ET DANS LA CONFERENCE GEODESIQUE DE FLORENCE, LE 8 OCTOBRE 1891, Neuchâtel, IMPRIMERIE ATTINGER FRERES, 1891, in COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DES POIDS ET MESURES, PROCÈS-VERBAUX DES SÉANCES DE 1891, Paris, GAUTHIER-VILLARS ET FILS, IMPRIMEURS-LIBRAIRES, 1892, 197 p., pp. 3–14

o

Don Carlos IBANEZ (1825–1891), 1892, 12 p.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ibáñez, Carlos 1825 births 1891 deaths Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Spanish geodesists Elected Members of the International Statistical Institute Fellows of the Royal Statistical Society