Carcassonne, Aude on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carcassonne is a French

The Gallic Wars

by Julius Caesar, edited by Vincent Rospond: ''Carsac was heCeltic place-name f a settlementwhich became an important trading place in the 6th century BCE. The Volcae Tectosages fortified it as an In 1240, Trencavel's son tried unsuccessfully to reconquer his old domain. The city submitted to the rule of the kingdom of France in 1247. Carcassonne became a border fortress between France and the

In 1240, Trencavel's son tried unsuccessfully to reconquer his old domain. The city submitted to the rule of the kingdom of France in 1247. Carcassonne became a border fortress between France and the

The fortified city consists essentially of a concentric design of two outer walls with 52 towers and

The fortified city consists essentially of a concentric design of two outer walls with 52 towers and

stage 11

of the

In May 2018, as the project "Concentric, eccentric" by French-Swiss artist Felice Varini, large yellow concentric circles were mounted on the monument as part of the 7th edition of "IN SITU, Heritage and contemporary art", a summer event in the Occitanie / Pyrenees-Mediterranean region focusing on the relationship between modern art and architectural heritage. This monumental work was done to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Carcassonne's inscription on the World Heritage List of

In May 2018, as the project "Concentric, eccentric" by French-Swiss artist Felice Varini, large yellow concentric circles were mounted on the monument as part of the 7th edition of "IN SITU, Heritage and contemporary art", a summer event in the Occitanie / Pyrenees-Mediterranean region focusing on the relationship between modern art and architectural heritage. This monumental work was done to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Carcassonne's inscription on the World Heritage List of

Official website of the city of Carcassonne

Cité de Carcassonne

from the French Ministry of Culture

{{Authority control Communes of Aude Cities in Occitania (administrative region) Prefectures in France Catharism Fortified settlements Medieval defences Populated places established in the 4th millennium BC Landmarks in France World Heritage Sites in France Languedoc Monuments of the Centre des monuments nationaux

fortified city

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications such as curtain walls with to ...

in the department of Aude

Aude ( ; ) is a Departments of France, department in Southern France, located in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region and named after the river Aude (river), Aude. The departmental council also calls it " ...

, region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

of Occitania

Occitania is the historical region in Southern Europe where the Occitan language was historically spoken and where it is sometimes used as a second language. This cultural area roughly encompasses much of the southern third of France (except ...

. It is the prefecture

A prefecture (from the Latin word, "''praefectura"'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain inter ...

of the department.

Inhabited since the Neolithic Period

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wid ...

, Carcassonne is located in the plain of the Aude

Aude ( ; ) is a Departments of France, department in Southern France, located in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region and named after the river Aude (river), Aude. The departmental council also calls it " ...

between historic trade routes, linking the Atlantic to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and the Massif Central to the Pyrénées

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto.

F ...

. Its strategic importance was quickly recognised by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, who occupied its hilltop until the demise of the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

. In the fifth century, the region of Septimania

Septimania is a historical region in modern-day southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of '' Gallia Narbonensis'' that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septimania was ceded to their king, Theod ...

was taken over by the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian military group unite ...

, who founded the city of Carcassonne in the newly established Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths () was a Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic people ...

.

Its citadel, known as the Cité de Carcassonne

The Cité de Carcassonne ( ) is a medieval citadel located in the French city of Carcassonne, in the Aude department, Occitania region. It is situated on a hill on the right bank of the river Aude, in the south-eastern part of the city proper.

...

, is a medieval fortress dating back to the Gallo-Roman period

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire in Roman Gaul. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely ...

and restored by the theorist and architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (; 27 January 181417 September 1879) was a French architect and author, famous for his restoration of the most prominent medieval landmarks in France. His major restoration projects included Notre-Dame de Paris, ...

between 1853 and 1879. It was added to the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

list of World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s in 1997 because of the exceptional preservation and restoration of the medieval citadel. Consequently, Carcassonne relies heavily on tourism but also counts manufacturing and winemaking

Winemaking, wine-making, or vinification is the production of wine, starting with the selection of the fruit, its Ethanol fermentation, fermentation into alcohol, and the bottling of the finished liquid. The history of wine-making stretches over ...

as some of its other key economic sectors.

Geography

Carcassonne is located in the south of France about east ofToulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

. Its strategic location between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea has been known since the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

era. The town's area is about , which is significantly larger than the numerous small towns in the department of Aude. The rivers Aude, Fresquel, and the Canal du Midi

The Canal du Midi (; ) is a long canal in Southern France (). Originally named the ''Canal Royal en Languedoc'' (Royal Canal in Languedoc) and renamed by French revolutionaries to ''Canal du Midi'' in 1789, the canal is considered one of the g ...

flow through the town.

History

The first signs of settlement in this region have been dated to about 3500 BC, but the hill site of ''Carsac''—aCeltic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

place-name

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper nam ...

that has been retained at other sites in the south—became an important trading place in the sixth century BC. The Volcae Tectosages

The Volcae () were a Gallic tribal confederation constituted before the raid of combined Gauls that invaded Macedonia c. 270 BC and fought the assembled Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae in 279 BC. Tribes known by the name Volcae were found sim ...

fortified it and made it into an ''oppidum

An ''oppidum'' (: ''oppida'') is a large fortified Iron Age Europe, Iron Age settlement or town. ''Oppida'' are primarily associated with the Celts, Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread acros ...

'', a hill fort, which is when it was named "Carsac".Explanation about "Carsac" in Appendix VI oThe Gallic Wars

by Julius Caesar, edited by Vincent Rospond: ''Carsac was heCeltic place-name f a settlementwhich became an important trading place in the 6th century BCE. The Volcae Tectosages fortified it as an

oppidum

An ''oppidum'' (: ''oppida'') is a large fortified Iron Age Europe, Iron Age settlement or town. ''Oppida'' are primarily associated with the Celts, Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread acros ...

. The Latin name for this place was Carcaso, which today is called Carcassonne. Carsac became strategically identified when heRomans fortified the hilltop around 100 BCE and eventually made it the colonia of Julia Carsaco, later Carcasum. The main part of the lower courses of the northern ramparts dates from Gallo-Roman times.''

The folk etymology

Folk etymology – also known as (generative) popular etymology, analogical reformation, (morphological) reanalysis and etymological reinterpretation – is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a mo ...

—involving a châtelain

Châtelain was originally the French title for the keeper of a castle.Abraham Rees Ebers, "CASTELLAIN", in: The Cyclopædia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature' (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1819), vol. 6.

H ...

e named Lady Carcas The legend of Lady Carcas () is an etiological story about the origin of Carcassonne's name.

The legend

The legend takes place in the 8th century, during the wars between Christians and Muslims in the southwest of Europe. At the time, Carcassonne ...

, a ruse ending a siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

, and the joyous ringing of bells (" sona")—though memorialized in a neo-Gothic

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century ...

sculpture of ''Mme. '' on a column near the Narbonne Gate, is a modern reconstruction of a 16th century depiction. The name can be derived as an augmentative

An augmentative (abbreviated ) is a morphological form of a word which expresses greater intensity, often in size but also in other attributes. It is the opposite of a diminutive.

Overaugmenting something often makes it grotesque and so in so ...

of the name Carcas.

Carcassonne became strategically identified when the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

fortified the hilltop around 100 BC and eventually made it the of ''Julia Carsaco'', later ''Carcaso'', later ''Carcasum'' (by the process of swapping consonants known as metathesis). The main part of the lower courses of the northern ramparts dates from Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization (cultural), Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire in Roman Gaul. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, Roman culture, language ...

times. In AD 462 the Romans officially ceded Septimania

Septimania is a historical region in modern-day southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of '' Gallia Narbonensis'' that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septimania was ceded to their king, Theod ...

to the Visigothic

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied barbarian military group united under the comman ...

king Theodoric II

Theodoric II ( 426 – early 466) was the eighth King of the Visigoths, from 453 to 466.

Biography

Theoderic II, son of Theodoric I, obtained the throne by killing his elder brother Thorismund. The English historian Edward Gibbon writes that ...

who had held Carcassonne since AD 453.

Theodoric is thought to have begun the predecessor of the basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek Eas ...

that is now dedicated to Saint Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; ) is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean. The town is at the south of the seco ...

. In AD 508 the Visigoths successfully foiled attacks by the Frankish king

The Franks, Germanic peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dux, dukes and monarch, reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Franks, Salian Mero ...

Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

. In Francia

The Kingdom of the Franks (), also known as the Frankish Kingdom, or just Francia, was the largest History of the Roman Empire, post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks, Frankish Merovingian dynasty, Merovingi ...

, the Arab and Berber Muslim forces invaded

An invasion is a military offensive of combatants of one geopolitical entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory controlled by another similar entity, often involving acts of aggression.

Generally, invasions have objectives of co ...

the region of Septimania

Septimania is a historical region in modern-day southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of '' Gallia Narbonensis'' that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septimania was ceded to their king, Theod ...

in AD 719 and deposed the local Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths () was a Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic people ...

in AD 720; after the Frankish conquest of Narbonne in 759, the Muslim Arabs and Berbers were defeated by the Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

and retreated to Andalusia after 40 years of occupation, and the Carolingian king Pepin the Short

the Short (; ; ; – 24 September 768), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian dynasty, Carolingian to become king.

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude of H ...

came up reinforced.

A medieval fiefdom, the county of Carcassonne The County of Carcassonne (Occitan: ''Comtat de Carcassona'') was a medieval fiefdom controlling the city of Carcassonne, France, and its environs. It was often united with the County of Razès.

The origins of Carcassonne as a county probably go b ...

, controlled the city and its environs. It was often united with the county of Razès

The County of Razès was a feudal jurisdiction in Occitania, south of the County of Carcassonne, in what is now Southern France. It was founded in 781, after the creation of the Kingdom of Aquitania, when Septimania was separated from that state ...

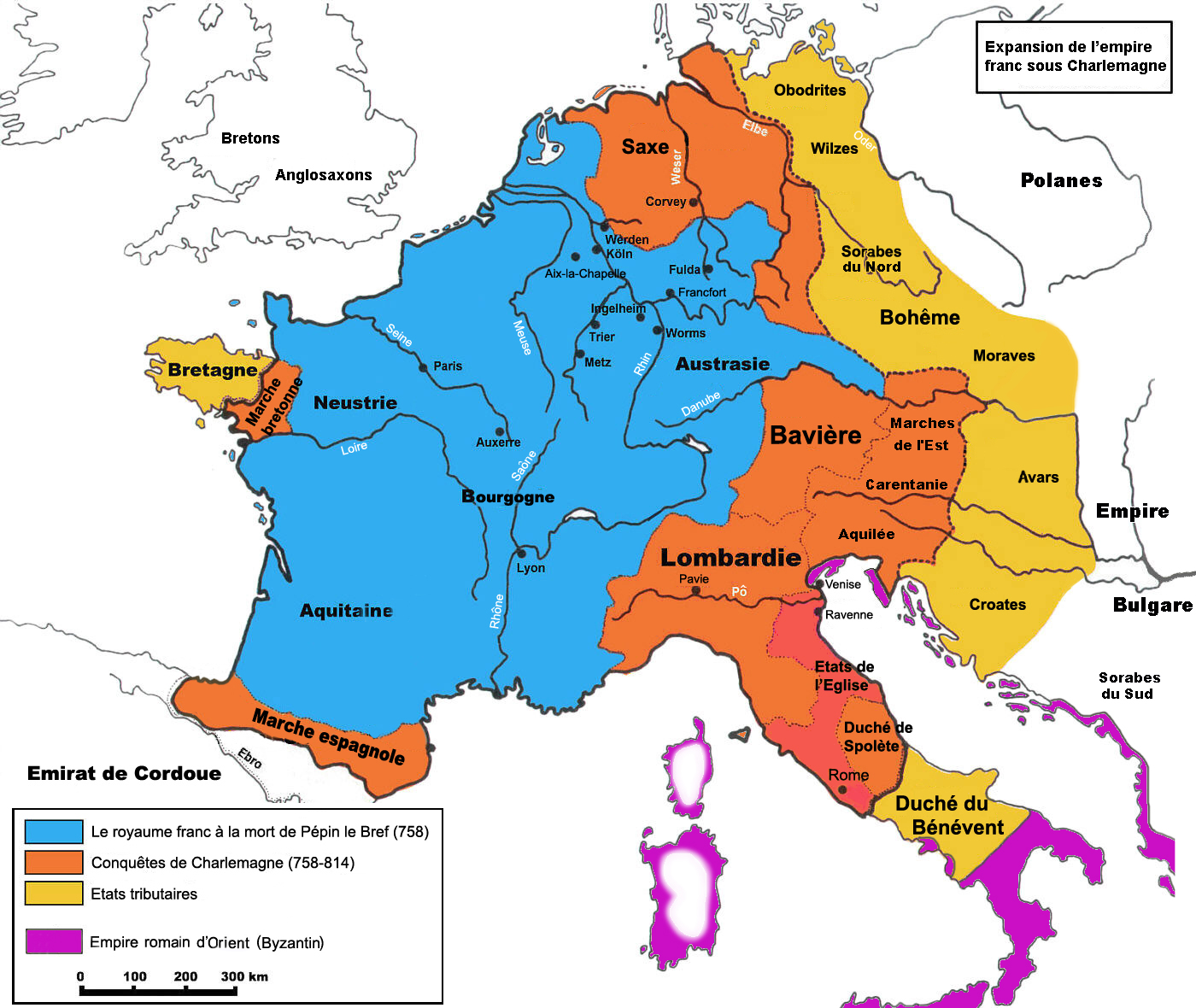

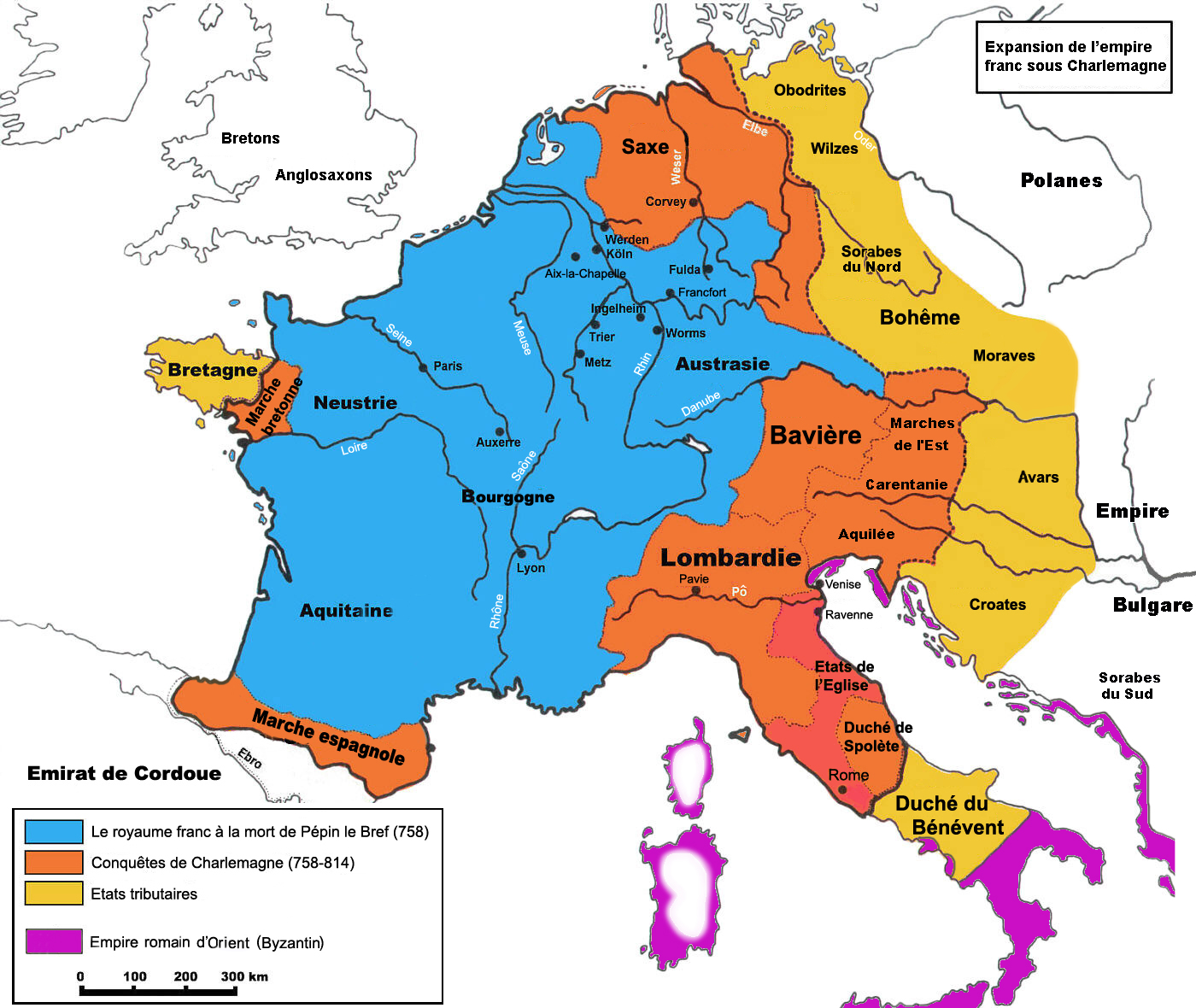

. The origins of Carcassonne as a county probably lie in local representatives of the Visigoths, but the first count known by name is Bello of the time of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

. Bello founded a dynasty, the Bellonids The Bellonids (, , ), sometimes called the Bellonid Dynasty, were the counts descended from the Goth Belló who ruled in Carcassonne, Urgell, Cerdanya, County of Conflent, Barcelona, and numerous other Hispanic and Gothic march counties in the ...

, which would rule many ''honores'' in Septimania and Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

for three centuries. In 1067, Carcassonne became the property of Raimond-Bernard Trencavel, viscount

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status. The status and any domain held by a viscount is a viscounty.

In the case of French viscounts, the title is ...

of Albi

Albi (; ) is a commune in France, commune in southern France. It is the prefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department, on the river Tarn (river), Tarn, 85 km northeast of Toulouse. Its inhabitants are called ...

and Nîmes

Nîmes ( , ; ; Latin: ''Nemausus'') is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Gard Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region of Southern France. Located between the Med ...

, through his marriage with Ermengard, sister of the last count of Carcassonne. In the following centuries, the Trencavel

The Trencavel family was an important French noble family in Languedoc between the 10th and 13th centuries. The name "Trencavel" began as a nickname and later became the family's surname. The name may derive from the Occitan words for "Nutcrac ...

family allied in succession with either the counts of Barcelona or of Toulouse. They built the ''Château Comtal'' and the Basilica of Saints Nazarius and Celsus. In 1096, Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II (; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening the Council of Clermon ...

blessed the foundation stones of the new cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

.

Carcassonne became famous for its role in the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

s when the city was a stronghold of Occitan Cathars

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

. In August 1209 the crusading army of the Papal Legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, abbot Arnaud Amalric

Arnaud Amalric (; died 1225), also known as Arnaud Amaury, was a Cistercians, Cistercian abbot who played a prominent role in the Albigensian Crusade. It is purported that prior to the Massacre at Béziers, massacre of Béziers, Amalric, when aske ...

, forced its citizens to surrender. Viscount Raymond-Roger de Trencavel was imprisoned while negotiating his city's surrender and died in mysterious circumstances three months later in his dungeon. The people of Carcassonne were allowed to leave—in effect, expelled from their city with nothing more than the shirts on their backs. Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, 1st Earl of Chester ( – 4 August 1265), also known as Simon V de Montfort, was an English nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the baronial opposition to the rule of ...

was appointed the new viscount and added to the fortifications.

In 1240, Trencavel's son tried unsuccessfully to reconquer his old domain. The city submitted to the rule of the kingdom of France in 1247. Carcassonne became a border fortress between France and the

In 1240, Trencavel's son tried unsuccessfully to reconquer his old domain. The city submitted to the rule of the kingdom of France in 1247. Carcassonne became a border fortress between France and the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon (, ) ;, ; ; . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona (later Principality of Catalonia) and ended as a consequence of the War of the Sp ...

under the 1258 Treaty of Corbeil. King Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis ...

founded the new part of the town across the river. He and his successor Philip III built the outer ramparts. Contemporary opinion still considered the fortress impregnable. During the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Edward III of England. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, succeeded to the throne instead. Edward n ...

failed to take the city in 1355, although his troops destroyed the lower town.

In 1659, the Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees(; ; ) was signed on 7 November 1659 and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa River on ...

transferred the border province of Roussillon

Roussillon ( , , ; , ; ) was a historical province of France that largely corresponded to the County of Roussillon and French Cerdagne, part of the County of Cerdagne of the former Principality of Catalonia. It is part of the region of ' ...

to France, and Carcassonne's military significance was reduced. Its fortifications were abandoned and the city became mainly an economic center of the wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

len textile industry, for which a 1723 source quoted by Fernand Braudel

Fernand Paul Achille Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' (1955–79), and the un ...

found it "the manufacturing center of Languedoc". It remained so until the Ottoman market collapsed at the end of the eighteenth century, then reverted to a country town. The town hall, known as Hôtel de Rolland, was completed in 1761.

Historical importance

Duringsiege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

s, temporary wooden platforms and walls would be fitted to the upper walls of the fortress through square holes in the face of the wall, providing protection to defenders on the wall and allowing defenders to go out past the wall to drop projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found ...

s on attackers at the wall beneath.

Main sights

The fortified city

The fortified city consists essentially of a concentric design of two outer walls with 52 towers and

The fortified city consists essentially of a concentric design of two outer walls with 52 towers and barbican

A barbican (from ) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe

Medieval Europeans typically b ...

s to prevent attack by siege engines. The castle itself possesses its own drawbridge and ditch leading to a central keep. The walls consist of towers built over quite a long period. One section is Roman and is notably different from the medieval walls, with the tell-tale red brick layers and the shallow pitch terracotta tile roofs. One of these towers housed the Catholic Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic judicial procedure where the ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various medieval and reformation-era state-organized tribunal ...

in the 13th century and is still known as "The Inquisition Tower".

Carcassonne was demilitarised under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

and the Restoration, and the fortified ''cité'' of Carcassonne fell into such disrepair that the French government decided that it should be demolished. A decree to that effect that was made official in 1849 caused an uproar. The antiquary and mayor of Carcassonne, Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille, and the writer Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée (; 28 September 1803 – 23 September 1870) was a French writer in the movement of Romanticism, one of the pioneers of the novella, a short novel or long short story. He was also a noted archaeologist and historian, an import ...

, the first inspector of ancient monuments, led a campaign to preserve the fortress as a historical monument. Later in the year the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (; 27 January 181417 September 1879) was a French architect and author, famous for his restoration of the most prominent medieval landmarks in France. His major restoration projects included Notre-Dame de Paris, ...

, already at work restoring the Basilica of Saints Nazarius and Celsus, was commissioned to renovate the place.

In 1853, work began with the west and southwest walls, followed by the towers of the ''porte Narbonnaise'' and the principal entrance to the ''cité''. The fortifications were consolidated here and there, but the chief attention was paid to restoring the roofing of the towers and the ramparts, where Viollet-le-Duc ordered the destruction of structures that had encroached against the walls, some of them of considerable age. Viollet-le-Duc left copious notes and drawings upon his death in 1879 when his pupil Paul Boeswillwald

Paul Louis Boeswillwald (October 22, 1844, in Paris – July 17, 1931, in Paris) was a French architect and art historian.

Biography

Son of the architect Émile Boeswillwald and father of the painter Émile Artus Boeswillwald, he was a pupil ...

and, later, the architect Nodet continued the rehabilitation of Carcassonne.

The restoration was strongly criticized during Viollet-le-Duc's lifetime. Fresh from work in the north of France, he made the error of using slate (when there was no slate to be quarried around) instead of terracotta

Terracotta, also known as terra cotta or terra-cotta (; ; ), is a clay-based non-vitreous ceramic OED, "Terracotta""Terracotta" MFA Boston, "Cameo" database fired at relatively low temperatures. It is therefore a term used for earthenware obj ...

tiles. The slate roofs were claimed to be more typical of northern France, as was the addition of the pointed tips to the roofs.

Lower town

The ville basse dates to theLate Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

. Founded as a settlement of the expelled inhabitants of the town sometime after the crusades, it has been the economic heart of the city for centuries. Though once walled, most of the walls in this portion of the town are no longer intact. The Carcassonne Cathedral

Carcassonne Cathedral (French language, French: ''Cathédrale Saint-Michel de Carcassonne'') is a cathedral and designated Monument historique, national monument in Carcassonne, France. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic ...

is in this part of the town.

Other

Another bridge, Pont Marengo, crosses the Canal du Midi and provides access to therailway station

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

. The Lac de la Cavayère has been created as a recreational lake; it is about five minutes from the city centre by automobile.

Further sights include:

* The Basilica of Saints Nazarius and Celsus

* The Carcassonne Cathedral

Carcassonne Cathedral (French language, French: ''Cathédrale Saint-Michel de Carcassonne'') is a cathedral and designated Monument historique, national monument in Carcassonne, France. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic ...

* Church of St. Vincent

Climate

Carcassonne has ahumid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a subtropical -temperate climate type, characterized by long and hot summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

: Cfa), though with noticeable hot-summer mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

influence (Köppen climate classification: Csa), a climate which is more typical of southern France, with moderately wet and mild winters coupled with summers averaging above during daytime with low rainfall.

Carcassonne, along with the French Mediterranean coastline, can be subject to intense thunderstorms and torrential rains in late summer and early autumn. The Carcassonne region can be flooded in such events, the last of which happened on 14–15 October 2018.

Population

Economy

The newer part (''Ville Basse'') of the city on the other side of the Aude river (which dates back to the Middle Ages, after the crusades) manufactures shoes,rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

and textiles. It is also the center of a major AOC winegrowing region. A major part of its income comes from the tourism connected to the fortifications (''Cité'') and from boats cruising on the Canal du Midi

The Canal du Midi (; ) is a long canal in Southern France (). Originally named the ''Canal Royal en Languedoc'' (Royal Canal in Languedoc) and renamed by French revolutionaries to ''Canal du Midi'' in 1789, the canal is considered one of the g ...

. Carcassonne is also home to the MKE Performing Arts Academy. Carcassonne receives about three million visitors annually.

Transport

In the late 1990s, Carcassonne airport started taking budget flights to and from European airports and by 2009 had regular flight connections withPorto

Porto (), also known in English language, English as Oporto, is the List of cities in Portugal, second largest city in Portugal, after Lisbon. It is the capital of the Porto District and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto c ...

, Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

, Cork

"Cork" or "CORK" may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Stopper (plug), or "cork", a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

*** Wine cork an item to seal or reseal wine

Places Ireland

* ...

, Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, Frankfurt-Hahn

Hahn Airporthahn-airport.de

retrieved 30 April 2025 () , also colloquially known and formerly officially br ...

, retrieved 30 April 2025 () , also colloquially known and formerly officially br ...

London-Stansted

Stansted Airport is an international airport serving London, the capital of England and the United Kingdom. It is located near Stansted Mountfitchet, Uttlesford, Essex, northeast of Central London.

As London's third-busiest airport, Stan ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, East Midlands

The East Midlands is one of nine official regions of England. It comprises the eastern half of the area traditionally known as the Midlands. It consists of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire (except for North Lincolnshire and North East ...

, Glasgow-Prestwick and Charleroi

Charleroi (, , ; ) is a city and a municipality of Wallonia, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It is the largest city in both Hainaut and Wallonia. The city is situated in the valley of the Sambre, in the south-west of Belgium, not ...

.

The Gare de Carcassonne railway station offers direct connections to Toulouse, Narbonne, Perpignan, Paris, Marseille, and several regional destinations. The A61 motorway connects Carcassonne with Toulouse and Narbonne.

Education

*École nationale de l'aviation civile

École nationale de l'aviation civile (; "National School of Civil Aviation"; abbr. ENAC) is one of 205 colleges (as of September 2018) accredited to award engineering degrees in Education in France, France. ENAC is designated as a grande école ...

Language

French is spoken. Historically, the language spoken in Carcassonne and throughout Languedoc-Roussillon was not French butOccitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

.

Sport

In July 2021, Carcassonne was the finish city for stage 13, and the starting point of stage 14, of the2021 Tour de France

The 2021 Tour de France was the 108th edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's three Grand Tour (cycling), grand tours. Originally planned for the Denmark, Danish capital of Copenhagen, the start of the 2021 Tour (known as the ) was trans ...

. It was at the finish in Carcassonne that Mark Cavendish

Sir Mark Simon Cavendish (born 21 May 1985) is a Manx people, Manx retired professional cyclist. As a Track cycling, track cyclist he specialised in the Madison (cycling), madison, points race, and scratch race disciplines; as a road racer he ...

tied the record for most Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage cycle sport, bicycle race held primarily in France. It is the oldest and most prestigious of the three Grand Tour (cycling), Grand Tours, which include the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a ...

stage wins (34) held by Eddy Merckx

Édouard Louis Joseph, Baron Merckx (born 17 June 1945), known as Eddy Merckx (, ), is a Belgian former professional road and track cyclist racer who is the most successful rider in the history of competitive cycling. His victories include an ...

. Carcassonne was the finish city for stage 15, and the starting point of stage 16, of the 2018 Tour de France

The 2018 Tour de France was the 105th edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's three Grand Tour (cycling), Grand Tours. The -long race consisted of 21 race stage, stages, starting on 7 July in Noirmoutier-en-l'Île, in western France, and ...

. Previously it was the starting point fostage 11

of the

2016 Tour de France

The 2016 Tour de France was the 103rd edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The -long race consisted of 21 stages, starting on 2 July in Mont Saint-Michel, Normandy, and concluding on 24 July with the Champs-Élysées s ...

, the starting point for a stage in the 2004 Tour de France

The 2004 Tour de France was a multiple stage bicycle race held from 3 to 25 July, and the 91st edition of the Tour de France. It has no overall winner—although American cyclist Lance Armstrong originally won the event, the United States Ant ...

, and a stage finish in the 2006 Tour de France

The 2006 Tour de France was the 93rd edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tour (cycling), Grand Tours. It took place between the 1st and the 23rd of July. It was won by Óscar Pereiro following the disqualification of Floyd Land ...

.

As in the rest of the southwest of France, rugby union

Rugby union football, commonly known simply as rugby union in English-speaking countries and rugby 15/XV in non-English-speaking world, Anglophone Europe, or often just rugby, is a Contact sport#Terminology, close-contact team sport that orig ...

is popular in Carcassonne. The city is represented by Union Sportive Carcassonnaise, known locally simply as USC. The club has a proud history, having played in the French Championship Final in 1925, and currently competes in Pro D2

The Pro D2 is the second tier of rugby union club competition division in France. It is operated by Ligue Nationale de Rugby (LNR) which also runs the division directly above, the first division Top 14. Rugby Pro D2 was introduced in 2000. It ...

, the second tier of French rugby.

Rugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as rugby league in English-speaking countries and rugby 13/XIII in non-Anglophone Europe, is a contact sport, full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular Rugby league playin ...

is also played, by the AS Carcassonne

Association Sportive of Carcassonne are a semi-professional rugby league football club based in Carcassonne in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie in the south of France. They play in the French Super XIII and are one of th ...

club. They are involved in the Elite One Championship

Super XIII is the top level rugby league competition in France, sanctioned by the French Rugby League Federation. The season runs from September to April, which is in contrast to the majority of other major domestic rugby league competitions ...

. Puig Aubert

Puig Aubert (born Robert Aubert Puig, 24 March 1925 – 3 June 1994), is often considered the best French rugby league footballer of all time. Over a 16-year professional career he would play for AS Carcassonne, Carcassonne, XIII Catalan, Celtic ...

is the most notable rugby league player to come from the Carcassonne club. There is a bronze statue of him outside the Stade Albert Domec

Stade Albert Domec is a multi-use municipal stadium in Carcassonne, France. It has a capacity of 10,000 spectators. It is the home ground of Pro D2 rugby union club US Carcassonne, Union Sportive Carcassonnaise and Elite One Championship rugby lea ...

at which the city's teams in both codes play.

Arts

In May 2018, as the project "Concentric, eccentric" by French-Swiss artist Felice Varini, large yellow concentric circles were mounted on the monument as part of the 7th edition of "IN SITU, Heritage and contemporary art", a summer event in the Occitanie / Pyrenees-Mediterranean region focusing on the relationship between modern art and architectural heritage. This monumental work was done to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Carcassonne's inscription on the World Heritage List of

In May 2018, as the project "Concentric, eccentric" by French-Swiss artist Felice Varini, large yellow concentric circles were mounted on the monument as part of the 7th edition of "IN SITU, Heritage and contemporary art", a summer event in the Occitanie / Pyrenees-Mediterranean region focusing on the relationship between modern art and architectural heritage. This monumental work was done to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Carcassonne's inscription on the World Heritage List of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

.

Exceptional in its size and its visibility and use of architectural space, the exhibit extended across the western front of the fortifications of the city. The work could be fully perceived only in front of the Porte d'Aude at the pedestrian route from the Bastide

Bastides are fortified new towns built in medieval Languedoc, Gascony, Aquitaine, England and Wales during the 13th and 14th centuries, although some authorities count Mont-de-Marsan and Montauban, which was founded in 1144, as the first bastides ...

. The circles of yellow colour consist of thin, painted aluminium sheets, spread like waves of time and space, fragmenting and recomposing the geometry of the circles on the towers and curtain walls of the fortifications. The work was visible from May to September 2018 only.

In culture

* The French poet Gustave Nadaud made Carcassonne famous as a city. He wrote a poem about a man who dreamed of seeing but could not see before he died. His poem inspired many others and was translated into English several times.Georges Brassens

Georges Charles Brassens (; ; 22 October 1921 – 29 October 1981) was a French singer-songwriter and poet.

As an iconic figure in France, he achieved fame through his elegant songs with their harmonically complex music for voice and guitar and ...

has sung a musical version of the poem. Lord Dunsany

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany (; 24 July 1878 – 25 October 1957), commonly known as Lord Dunsany, was an Anglo-Irish writer and dramatist. He published more than 90 books during his lifetime, and his output consist ...

wrote a short story "Carcassonne" (in ''A Dreamer's Tales'') as did William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

.

*On 6 March 2000 France issued a stamp commemorating the fortress of Carcassonne.

*In 2000, the popular board game Carcassonne (board game)

''Carcassonne'' () is a tile-based German-style board game for two to five players, designed by Klaus-Jürgen Wrede and published in 2000 by Hans im Glück in German and by Rio Grande Games (until 2012) and Z-Man Games (currently) in En ...

was released. While exploring the area for inspiration, the creator, Klaus-Jürgen Wrede

Klaus-Jürgen Wrede (born 1963 in Meschede, North Rhine-Westphalia) is a German board game creator, the creator of the best-selling ''Carcassonne (board game), Carcassonne'' and ''Downfall of Pompeii''.

Early life

Born to music-teacher parents in ...

, "was so impressed by the whole landscape and area surrounding Carcassonne" that he "wanted to build it in a game".

*It was the inspiration for the Black Ops 6 Zombie Map "Citadelle des Morts" (Citadel of the Dead).

*It was the titular destination in the book ''Narrow Dog to Carcassonne'' journalling a couple's trip from England to the Mediterranean coast of France aboard their narrowboat

A narrowboat is a particular type of Barge, canal boat, built to fit the narrow History of the British canal system, locks of the United Kingdom. The UK's canal system provided a nationwide transport network during the Industrial Revolution, b ...

.

People

* Paul Lacombe, French composer, b. 1837 * Théophile Barrau, French sculptor, b. 1848 * Paul Sabatier, French chemist, co-recipient of theNobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

, b. 1854

* Henry d'Estienne, French painter, b. 1872

* Suzanne Sarroca, French operatic soprano, b. 1927

* Gilbert Benausse, French rugby league footballer, b. 1932

*Alain Colmerauer

Alain Colmerauer (24 January 1941 – 12 May 2017) was a French computer scientist. He was a professor at Aix-Marseille University, and the creator of the logic programming language Prolog.

Early life

Alain Colmerauer was born on 24 January 1941 ...

, French computer scientist, inventor of the programming language Prolog

Prolog is a logic programming language that has its origins in artificial intelligence, automated theorem proving, and computational linguistics.

Prolog has its roots in first-order logic, a formal logic. Unlike many other programming language ...

, b. 1941

*Michael Martchenko

Michael Martchenko (born August 1, 1942) is a Canadian illustrator best known for illustrating many books by Robert Munsch.

Early life

Born in Carcassonne, France, Martchenko moved to Canada when he was seven, where he graduated from the Ontario ...

, French-born Canadian illustrator, b. 1942

*Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated the ...

, French soldier, General of Division during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, b. 1856

*David Ferriol

David Ferriol (born 24 April 1979) is a French former professional rugby league footballer. He previously played for the Catalans Dragons club in the Super League.

Background

Ferriol was born in Carcassonne, France.

Career

A powerful, ball-car ...

, French rugby league player, b. 1979

* Olivia Ruiz, French pop singer, b. 1980

*Fabrice Estebanez

Fabrice Estebanez (born 26 December 1981) is a French professional rugby league and rugby union footballer. He has played at club level for CA Brive before joining Racing Metro 92, as a utility back and is able to play as a centre or fly-half.

...

, French rugby union player, b. 1981

International relations

Carcassonne is twinned with: *Eggenfelden

Eggenfelden (; Central Bavarian: ''Eggenfejdn'') is a municipality in the district of Rottal-Inn in Bavaria, Germany.

Geography

Geographical location

Eggenfelden is located in the valley of the Rott (Inn, Neuhaus am Inn), Rott at the intersecti ...

, Germany

* Baeza, Spain

Baeza () is a city and municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Jaén, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is part of the ''comarca'' of La Loma. The present name was established in Roman times as ''Vivatia'', then ''Biatia'' ...

* Tallinn

Tallinn is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Estonia, most populous city of Estonia. Situated on a Tallinn Bay, bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, it has a population of (as of 2025) and ...

, Estonia

Notes

References

External links

Official website of the city of Carcassonne

Cité de Carcassonne

from the French Ministry of Culture

{{Authority control Communes of Aude Cities in Occitania (administrative region) Prefectures in France Catharism Fortified settlements Medieval defences Populated places established in the 4th millennium BC Landmarks in France World Heritage Sites in France Languedoc Monuments of the Centre des monuments nationaux