C.V.Raman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman ( ; ; 7 November 1888 – 21 November 1970) was an Indian

, Official Nobel prize biography, nobelprize.org His second paper published in the same journal that year was on surface tension of liquids. It was alongside

When he reached Calcutta, he asked his student K. R. Ramanathan, who was from the University of Rangoon, to conduct further research at IACS. By early 1922, Raman came to a conclusion, as he reported in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society of London'':True to his words, Ramanathan published an elaborate experimental finding in 1923. His subsequent study of the

When he reached Calcutta, he asked his student K. R. Ramanathan, who was from the University of Rangoon, to conduct further research at IACS. By early 1922, Raman came to a conclusion, as he reported in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society of London'':True to his words, Ramanathan published an elaborate experimental finding in 1923. His subsequent study of the

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Raman was honored with many honorary doctorates and memberships of scientific societies. Within India, apart from being the founder and President of the Indian Academy of Sciences (FASc), he was a Fellow of the

Raman was honored with many honorary doctorates and memberships of scientific societies. Within India, apart from being the founder and President of the Indian Academy of Sciences (FASc), he was a Fellow of the

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

known for his work in the field of light scattering

In physics, scattering is a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities (including particles and radia ...

.

Using a spectrograph

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

that he developed, he and his student K. S. Krishnan discovered that when light traverses a transparent material, the deflected light changes its wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

. This phenomenon, a hitherto unknown type of scattering of light, which they called ''modified scattering'' was subsequently termed the ''Raman effect'' or ''Raman scattering

In chemistry and physics, Raman scattering or the Raman effect () is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrationa ...

''. In 1930, Raman received the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

for this discovery and was the first Asian and non-White to receive a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

in any branch of science.

Born to Tamil Brahmin

Tamil Brahmins are an ethnoreligious community of Tamil-speaking Hindu Brahmins, predominantly living in Tamil Nadu, though they number significantly in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Telangana in addition to other regions of India. The ...

parents, Raman was a precocious child, completing his secondary and higher secondary education from St Aloysius' Anglo-Indian High School at the age of 11 and 13, respectively. He topped the bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Medieval Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six years ...

examination of the University of Madras

The University of Madras is a public university, public State university (India), state university in Chennai (Madras), Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and most prominent universities in India, incorporated by an ...

with honours in physics from Presidency College at age 16. His first research paper, on diffraction of light

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the Wave propagation ...

, was published in 1906 while he was still a graduate student. The next year he obtained a master's degree. He joined the Indian Finance Service in Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

as Assistant Accountant General at age 19. There he became acquainted with the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), the first research institute in India, which allowed him to carry out independent research and where he made his major contributions in acoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician ...

and optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

.

In 1917, he was appointed the first Palit Professor of Physics by Ashutosh Mukherjee

Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee (anglicised, originally Asutosh Mukhopadhyay, also anglicised to Asutosh Mookerjee) (29 June 1864 – 25 May 1924) was a Bengali mathematician, lawyer, jurist, judge, educator, and institution builder. A unique figure i ...

at the Rajabazar Science College

The University College of Science, Technology and Agriculture (formerly known as Rajabazar Science College) are two of five main campuses of the University of Calcutta (CU). The college served as the cradle of Indian sciences, where Raman won t ...

under the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

. On his first trip to Europe, seeing the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

motivated him to identify the prevailing explanation for the blue colour of the sea at the time, namely the reflected Rayleigh-scattered light from the sky, as being incorrect. He founded the '' Indian Journal of Physics'' in 1926. He moved to Bangalore

Bengaluru, also known as Bangalore (List of renamed places in India#Karnataka, its official name until 1 November 2014), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the southern States and union territories of India, Indian state of Kar ...

in 1933 to become the first Indian director of the Indian Institute of Science

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a Public university, public, Deemed university, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, Karnataka. The ...

. He founded the Indian Academy of Sciences

The Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore was founded by Indian Physicist and List of Nobel laureates, Nobel Laureate Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, C. V. Raman, and was registered as a society on 27 April 1934. Inaugurated on 31 July 1934, it ...

the same year. He established the Raman Research Institute in 1948 where he worked to his last days.

The Raman effect was discovered on 28 February 1928. The day is celebrated annually by the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO 15919, ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of States and union t ...

as the National Science Day.

Early life and education

Raman was born inTiruchirappalli

Tiruchirappalli (), also known as Trichy, is a major tier II city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Tiruchirappalli district. The city is credited with being the best livable and the cleanest city of T ...

in the Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency or Madras Province, officially called the Presidency of Fort St. George until 1937, was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India and later the Dominion of India. At its greatest extent, the presidency i ...

of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

(now Tiruchirapalli

Tiruchirappalli (), also known as Trichy, is a major tier II city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Tiruchirappalli district. The city is credited with being the best livable and the cleanest city of Ta ...

, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

, India) to Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

Iyer Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

parents, Chandrasekhar Ramanathan Iyer and Parvathi Ammal. He was the second of eight siblings. His father was a teacher at a local high school, and earned a modest income. He recalled: "I was born with a copper spoon in my mouth. At my birth my father was earning the magnificent salary of ten rupees per month!" In 1892, his family moved to Visakhapatnam

Visakhapatnam (; List of renamed places in India, formerly known as Vizagapatam, and also referred to as Vizag, Visakha, and Waltair) is the largest and most populous metropolitan city in the States and union territories of India, Indian stat ...

(then Vizagapatam or Vizag) in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (ISO 15919, ISO: , , AP) is a States and union territories of India, state on the East Coast of India, east coast of southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, seventh-largest state and th ...

as his father was appointed to the faculty of physics at Mrs A.V. Narasimha Rao College.

Raman was educated at the St Aloysius' Anglo-Indian High School, Visakhapatnam

Visakhapatnam (; List of renamed places in India, formerly known as Vizagapatam, and also referred to as Vizag, Visakha, and Waltair) is the largest and most populous metropolitan city in the States and union territories of India, Indian stat ...

. He passed matriculation at age 11 and the First Examination in Arts examination (equivalent to today's intermediate examination, pre-university course

According to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), basic education comprises the two stages primary education and lower secondary education.

Universal basic education

Basic education featured heavily in the 1997 ISCED ...

) with a scholarship at age 13, securing first position in both under the Andhra Pradesh school board (now Andhra Pradesh Board of Secondary Education) examination.

In 1902, Raman joined Presidency College in Madras (now Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

) where his father had been transferred to teach mathematics and physics. In 1904, he obtained a B.A. degree from the University of Madras

The University of Madras is a public university, public State university (India), state university in Chennai (Madras), Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and most prominent universities in India, incorporated by an ...

, where he stood first and won the gold medals in physics and English. At age 18, while still a graduate student, he published his first scientific paper on "Unsymmetrical diffraction bands due to a rectangular aperture" in the British journal ''Philosophical Magazine

The ''Philosophical Magazine'' is one of the oldest scientific journals published in English. It was established by Alexander Tilloch in 1798;John Burnett"Tilloch, Alexander (1759–1825)" Dictionary of National Biography#Oxford Dictionary of ...

'' in 1906. He earned an M.A. degree from the same university with highest distinction in 1907.The Nobel Prize in Physics 1930 Sir Venkata Raman, Official Nobel prize biography, nobelprize.org His second paper published in the same journal that year was on surface tension of liquids. It was alongside

Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh ( ; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919), was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 "for his investigations of the densities of the most important gases and for his discovery ...

's paper on the sensitivity of ear to sound, and from which Lord Rayleigh started to communicate with Raman, courteously addressing him as Professor.

Aware of Raman's capacity, his physics teacher Rhishard Llewellyn Jones insisted he continue research in England. Jones arranged for Raman's physical inspection with Colonel (Sir Gerald) Giffard. Raman often had poor health and was considered as a "weakling." The inspection revealed that he would not withstand the harsh weathers of England, the incident of which he later recalled, and said, " iffardexamined me and certified that I was going to die of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

... if I were to go to England."

Career

Raman's elder brother Chandrasekhara Subrahmanya Ayyar had joined the prestigious Indian government service, Indian Finance Service (now Indian Audit and Accounts Service). Raman followed suit and qualified for the Indian Finance Service achieving first position in the entrance examination in February 1907. He was posted in Calcutta (nowKolkata

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta ( its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River, west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary ...

) as Assistant Accountant General in June 1907.

He was highly impressed by the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), Calcutta, the first research institute founded in India in 1876. He immediately befriended Asutosh Dey (who would eventually become his lifelong collaborator), Amrita Lal Sircar (the founder Mahendralal Sircar's son and secretary of IACS), and Ashutosh Mukherjee

Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee (anglicised, originally Asutosh Mukhopadhyay, also anglicised to Asutosh Mookerjee) (29 June 1864 – 25 May 1924) was a Bengali mathematician, lawyer, jurist, judge, educator, and institution builder. A unique figure i ...

(executive member of the IACS and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

). With their support, he obtained permission to conduct research at IACS in his own time even "at very unusual hours," as Raman later reminisced. Up to that time the institute had not yet recruited regular researchers, or produced any research paper. Raman's article "Newton's rings in polarised light" published in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' in 1907 became the first from the institute. The work inspired IACS to publish a journal, ''Bulletin of Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science,'' in 1909 in which Raman was the major contributor.

In 1909, Raman was transferred to Rangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

, British Burma

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and cultur ...

(now Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

), to take up the position of currency officer. After only a few months, he had to return to Madras as his father died from an illness. The subsequent death of his father and funeral rituals compelled him to remain there for the rest of the year. Soon after he resumed office at Rangoon, he was transferred back to India at Nagpur

Nagpur (; ISO 15919, ISO: ''Nāgapura'') is the second capital and third-largest city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is called the heart of India because of its central geographical location. It is the largest and most populated city i ...

, Maharashtra, in 1910. Even before he served a year in Nagpur, he was promoted to Accountant General in 1911 and again posted to Calcutta.

From 1915, the University of Calcutta started assigning research scholars under Raman at IACS. Sudhangsu Kumar Banerji (who later become Director General of Observatories of India Meteorological Department

India Meteorological Department (IMD) is an Indian agency of the Ministry of Earth Sciences of the Government of India. It is the principal agency responsible for meteorological observations, weather forecasting and seismology. IMD is headquar ...

), a PhD scholar under Ganesh Prasad, was his first student. From the next year, other universities followed suit including University of Allahabad

The University of Allahabad is a Central university (India), Central University located in Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. It was established on 23 September 1887 by an act of Parliament and is recognised as an Institute of National Importance (INI). ...

, Rangoon University, Queen's College Indore, Institute of Science, Nagpur, Krisnath College, and University of Madras. By 1919, Raman had guided more than a dozen students. Following Sircar's death in 1919, Raman received two honorary positions at IACS, Honorary Professor and Honorary Secretary. He referred to this period as the "golden era" of his life.

Raman was chosen by the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

to become the Palit Professor of Physics, a position established after the benefactor Sir Taraknath Palit, in 1913. The university senate made the appointment on 30 January 1914, as recorded in the meeting minutes:Prior to 1914, Ashutosh Mukherjee had invited Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

to take up the position, but Bose declined. As a second choice, Raman became the first Palit Professor of Physics but was delayed for taking up the position as World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out. It was only in 1917 when he joined Rajabazar Science College

The University College of Science, Technology and Agriculture (formerly known as Rajabazar Science College) are two of five main campuses of the University of Calcutta (CU). The college served as the cradle of Indian sciences, where Raman won t ...

, a campus created by the University of Calcutta in 1914, that he became a full-fledged professor. He reluctantly resigned as a civil servant after a decade of service, which was described as "supreme sacrifice" since his salary as a professor would be roughly half of his salary at the time. But to his advantage, the terms and conditions as a professor were explicitly indicated in the report of his joining the university, which stated:Raman's appointment as the Palit Professor was strongly objected to by some members of the Senate of the University of Calcutta, especially foreign members, as he had no PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

and had never studied abroad. As a kind of rebuttal, Asutosh Mukherjee arranged for an honorary DSc DSC or Dsc may refer to:

Education

* Doctor of Science (D.Sc.)

* District Selection Committee, an entrance exam in India

* Doctor of Surgical Chiropody, superseded in the 1960s by Doctor of Podiatric Medicine

Educational institutions

* Dyal Sin ...

which the University of Calcutta conferred Raman in 1921. The same year he visited Oxford to deliver a lecture at the Congress of Universities of the British Empire. He had earned quite a reputation by then, and his hosts were Nobel laureates J. J. Thomson and Lord Rutherford. Upon his election as Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1924, Mukherjee asked him of his future plans, which he replied, saying, "The Nobel Prize of course." In 1926, he established the '' Indian Journal of Physics'' and acted as the first editor. The second volume of the journal published his famous article "A new radiation", reporting the discovery of the Raman effect.

Raman was succeeded by Debendra Mohan Bose as the Palit Professor in 1932. Following his appointment as Director of the Indian Institute of Science

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a Public university, public, Deemed university, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, Karnataka. The ...

(IISc) in Bangalore

Bengaluru, also known as Bangalore (List of renamed places in India#Karnataka, its official name until 1 November 2014), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the southern States and union territories of India, Indian state of Kar ...

, he left Calcutta in 1933. Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, the King of Mysore, Jamsetji Tata

Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata (3 March 1839 – 19 May 1904) was an Indian industrialist and philanthropist who founded the Tata Group, India's largest conglomerate. He established the city of Jamshedpur.

Born into a Zoroastrian Parsi family in ...

and Nawab

Nawab is a royal title indicating a ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the Western title of Prince. The relationship of a Nawab to the Emperor of India has been compared to that of the Kingdom of Saxony, Kings of ...

Sir Mir Osman Ali Khan, the Nizam of Hyderabad

Nizam of Hyderabad was the title of the ruler of Hyderabad State ( part of the Indian state of Telangana, and the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka). ''Nizam'' is a shortened form of (; ), and was the title bestowed upon Asaf Jah I wh ...

, had contributed the lands and funds for the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. The Viceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

, Lord Minto approved the establishment in 1909, and the British government appointed its first director, Morris Travers

Morris William Travers, FRS (24 January 1872 – 25 August 1961) was an English chemist who worked with Sir William Ramsay in the discovery of xenon, neon and krypton. His work on several of the rare gases earned him the name ''Rare Gas ...

. Raman became the fourth director and the first Indian director. During his tenure at IISc, he recruited G. N. Ramachandran, who later went on to become a distinguished X-ray crystallographer. He founded the Indian Academy of Sciences in 1934 and started publishing the academy's journal ''Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences'' (later split up into '' Proceedings - Mathematical Sciences, Journal of Chemical Sciences,'' and '' Journal of Earth System Science''). Around that time the Calcutta Physical Society was established, the concept of which he had initiated early in 1917.

With his former student Panchapakesa Krishnamurti, Raman started a company called Travancore Chemical and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. in 1943. The company, renamed as TCM Limited in 1996, was one of the first organic and inorganic chemical manufacturers in India. In 1947, Raman was appointed the first National Professor by the new government of independent India.

Raman retired from IISC in 1948 and established the Raman Research Institute in Bangalore a year later. He served as its director and remained active there until his death in 1970.

Scientific contributions

Musical sound

One of Raman's interests was on the scientific basis of musical sounds. He was inspired byHermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

's ''The Sensations of Tone'', the book he came across when he joined IACS. He published his findings prolifically between 1916 and 1921. He worked out the theory of transverse

Transverse may refer to:

*Transverse engine, an engine in which the crankshaft is oriented side-to-side relative to the wheels of the vehicle

*Transverse flute, a flute that is held horizontally

* Transverse force (or ''Euler force''), the tangen ...

vibration of bowed string instrument

Bowed string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by a bow (music), bow rubbing the string (music), strings. The bow rubbing the string causes vibration which the instrument emits as sound.

Despite the numerous spe ...

s based on superposition

In mathematics, a linear combination or superposition is an expression constructed from a set of terms by multiplying each term by a constant and adding the results (e.g. a linear combination of ''x'' and ''y'' would be any expression of the form ...

of velocities. One of his earliest studies was on the wolf tone in violins and cellos. He studied the acoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician ...

of various violin and related instruments, including Indian stringed instruments, and water splashes. He even performed what he called "Experiments with mechanically-played violins."

Raman also studied the uniqueness of Indian drums. His analyses of the harmonic

In physics, acoustics, and telecommunications, a harmonic is a sinusoidal wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'' of a periodic signal. The fundamental frequency is also called the ''1st har ...

nature of the sounds of tabla

A ''tabla'' is a pair of hand drums from the Indian subcontinent. Since the 18th century, it has been the principal percussion instrument in Hindustani classical music, where it may be played solo, as an accompaniment with other instruments a ...

and mridangam

The ''mridangam'' is an ancient percussion instrument originating from the Indian subcontinent. It is the primary rhythmic accompaniment in a Carnatic music ensemble. In Dhrupad, a modified version, the pakhawaj, is the primary percussion in ...

were the first scientific studies on Indian percussions. He wrote a critical research on vibrations of the pianoforte

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an action mechanism where hammers strike strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a chromatic scale in equal temp ...

string that was known as Kaufmann's theory. During his brief visit of England in 1921, he managed to study how sound travels in the Whispring Gallery of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

in London that produces unusual sound effects. His work on acoustics was an important prelude, both experimentally and conceptually, to his later works on optics and quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

.

Blue color of the sea

Raman, in his broadening venture on optics, started to investigate scattering of light starting in 1919. His first phenomenal discovery of the physics of light was the blue color of seawater. During a voyage home from England on board the ''S.S. Narkunda'' in September 1921, he contemplated the blue color of theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. Using simple optical equipment, a pocket-sized spectroscope

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

and a Nicol prism

A Nicol prism is a type of polarizer. It is an optical device made from calcite crystal used to convert ordinary light into plane polarized light. It is made in such a way that it eliminates one of the rays by total internal reflection, i.e. ...

in hand, he studied the sea water. Of several hypotheses on the colour of the sea propounded at the time, the best explanation had been that of Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh ( ; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919), was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1904 "for his investigations of the densities of the most important gases and for his discovery ...

's in 1910, according to which, "The much admired dark blue of the deep sea has nothing to do with the color of water, but is simply the blue of the sky seen by reflection". Rayleigh had correctly described the nature of the blue sky by a phenomenon now known as Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ) is the scattering or deflection of light, or other electromagnetic radiation, by particles with a size much smaller than the wavelength of the radiation. For light frequencies well below the resonance frequency of the scat ...

, the scattering of light and refraction by particles in the atmosphere. His explanation of the blue colour of water was instinctively accepted as correct. Raman could view the water using a Nicol prism

A Nicol prism is a type of polarizer. It is an optical device made from calcite crystal used to convert ordinary light into plane polarized light. It is made in such a way that it eliminates one of the rays by total internal reflection, i.e. ...

to avoid the influence of sunlight reflected by the surface. He described how the sea appears even more blue than usual, contradicting Rayleigh.

As soon as the ''S.S. Narkunda'' docked in Bombay Harbour (now Mumbai Harbour

Mumbai Harbour (also English; Bombay Harbour or Front Bay, Marathi ''Mumba'ī bandar''), is a natural deep-water harbour in the southern portion of the Ulhas River estuary. The narrower, northern part of the estuary is called Thana Creek. Th ...

), Raman finished an article "The colour of the sea" that was published in the November 1921 issue of ''Nature''. He noted that Rayleigh's explanation is "questionable by a simple mode of observation" (using Nicol prism). As he thought:

When he reached Calcutta, he asked his student K. R. Ramanathan, who was from the University of Rangoon, to conduct further research at IACS. By early 1922, Raman came to a conclusion, as he reported in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society of London'':True to his words, Ramanathan published an elaborate experimental finding in 1923. His subsequent study of the

When he reached Calcutta, he asked his student K. R. Ramanathan, who was from the University of Rangoon, to conduct further research at IACS. By early 1922, Raman came to a conclusion, as he reported in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society of London'':True to his words, Ramanathan published an elaborate experimental finding in 1923. His subsequent study of the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

in 1924 provided the full evidence. It is now known that the intrinsic color of water is mainly attributed to the selective absorption of longer wavelengths of light in the red and orange regions of the spectrum

A spectrum (: spectra or spectrums) is a set of related ideas, objects, or properties whose features overlap such that they blend to form a continuum. The word ''spectrum'' was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of co ...

, owing to overtones of the infrared

Infrared (IR; sometimes called infrared light) is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than that of visible light but shorter than microwaves. The infrared spectral band begins with the waves that are just longer than those ...

absorbing O-H (oxygen and hydrogen combined) stretching modes of water molecules.

Raman effect

Background

Raman's second important discovery on the scattering of light was a new type of radiation, an eponymous phenomenon called the Raman effect. After discovering the nature of light scattering that caused blue colour of water, he focused on the principle behind the phenomenon. His experiments in 1923 showed the possibility of other light rays formed in addition to the incident ray when sunlight was filtered through a violet glass in certain liquids and solids. Ramanathan believed that this was a case of a "trace offluorescence

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colore ...

." In 1925, K. S. Krishnan, a new Research Associate, noted the theoretical background for the existence of an additional scattering line beside the usual polarised elastic scattering when light scatters through liquid. He referred to the phenomenon as "feeble fluorescence." But the theoretical attempts to justify the phenomenon were quite futile for the next two years.

The major impetus was the discovery of Compton effect

Compton scattering (or the Compton effect) is the quantum theory of high frequency photons scattering following an interaction with a charged particle, usually an electron. Specifically, when the photon hits electrons, it releases loosely bound e ...

. Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American particle physicist who won the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiati ...

at Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) is a private research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1853 by a group of civic leaders and named for George Washington, the university spans 355 acres across its Danforth ...

had found evidence in 1923 that electromagnetic waves

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength, ran ...

can also be described as particles. By 1927, the phenomenon was widely accepted by scientists, including Raman. As the news of Compton's Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

was announced in December 1927, Raman ecstatically told Krishnan, saying:

But the origin of the inspiration went further. As Compton later recollected "that it was probably the Toronto debate that led him to discover the Raman effect two years later." The Toronto debate was about the discussion on the existence of light quantum at the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

meeting held at Toronto in 1924. There Compton presented his experimental findings, which William Duane of Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

argued with his own with evidence that light was a wave. Raman took Duane's side and said, "Compton, you're a very good debater, but the truth isn't in you."

The scattering experiments

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the visible spectrum

The visible spectrum is the spectral band, band of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visual perception, visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called ''visible light'' (or simply light).

The optica ...

of light. As Raman saw the result, he was astonished why he never observed such phenomenon all those years. That night he and Krishnan named the new phenomenon as "modified scattering" with reference to the Compton effect as an unmodified scattering. On 16 February, they sent a manuscript to ''Nature'' titled "A new type of secondary radiation", which was published on 31 March.

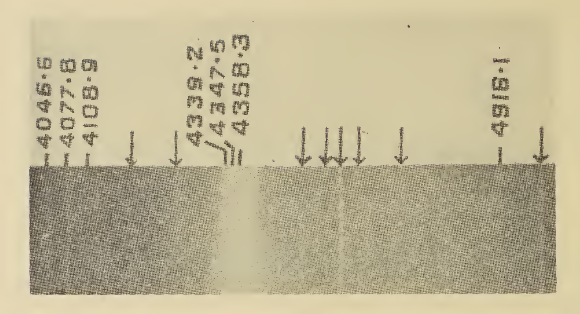

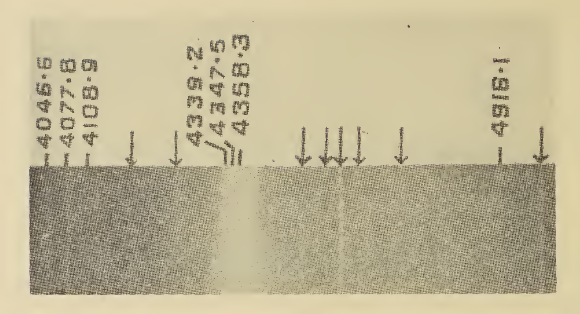

On 28 February 1928, they obtained spectra of the modified scattering separate from the incident light. Due to difficulty in measuring the wavelengths of light, they had been relying on visual observation of the colour produced from sunlight through prism. Raman had invented a type of spectrograph

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

for detecting and measuring electromagnetic waves. Referring to the invention, Raman later remarked, "When I got my Nobel Prize, I had spent hardly 200 rupees on my equipment," although it was obvious that his total expenditure for the entire experiment was much more than that. From that moment they could employ the instrument using monochromatic light

{{More citations needed, date=May 2023

In physics, monochromatic radiation is electromagnetic radiation with a single constant frequency or wavelength. When that frequency is part of the visible spectrum (or near it) the term monochromatic light ...

from a mercury arc lamp which penetrated transparent material and was allowed to fall on a spectrograph to record its spectrum. The lines of scattering could now be measured and photographed.Venkataraman, G. (1988) ''Journey into Light: Life and Science of C. V. Raman''. Oxford University Press. .

Announcement

The same day, Raman made the announcement before the press. The '' Associated Press of India'' reported it the next day, on 29 February, as "New theory of radiation: Prof. Raman's Discovery." It ran the story as:The news was reproduced by '' The Statesman'' on 1 March under the headline "Scattering of Light by Atoms – New Phenomenon – Calcutta Professor's Discovery." Raman submitted a three-paragraph report of the discovery on 8 March to ''Nature'' and was published on 21 April. The actual data was sent to the same journal on 22 March and was published on 5 May. Raman presented the formal and detailed description as "A new radiation" at the meeting of the South Indian Science Association in Bangalore on 16 March. His lecture was published in the '' Indian Journal of Physics'' on 31 March. A thousand copies of the paper reprint were sent to scientists in different countries on that day.Reception and outcome

Some physicists, particularly French and German physicists were initially sceptical of the authenticity of the discovery. Georg Joos at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena askedArnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in Atomic physics, atomic and Quantum mechanics, quantum physics, and also educated and ...

at the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich, LMU or LMU Munich; ) is a public university, public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Originally established as the University of Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke ...

, "Do you think that Raman's work on the optical Compton effect in liquids is reliable?... The sharpness of the scattered lines in liquids seems doubtful to me". Sommerfeld then tried to reproduce the experiment, but failed. On 20 June 1928, Peter Pringsheim at the University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

was able to reproduce Raman's results successfully. He was the first to coin the terms ''Ramaneffekt'' and ''Linien des Ramaneffekts'' in his articles published the following months. Use of the English versions, "Raman effect" and "Raman lines" immediately followed.

In addition to being a new phenomenon itself, the Raman effect was one of the earliest proofs of the quantum nature of light. Robert W. Wood

Robert Williams Wood (May 2, 1868 – August 11, 1955) was an American physicist and inventor who made pivotal contributions to the field of optics. He pioneered infrared and ultraviolet photography. Wood's patents and theoretical work inform m ...

at the Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

was the first American to confirm the Raman effect in early 1929. He made a series of experimental verification, after which he commented, saying, "It appears to me that this very beautiful discovery which resulted from Raman's long and patient study of the phenomenon of light scattering is one of the most convincing proofs of the quantum theory". The field of Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy () (named after physicist C. V. Raman) is a Spectroscopy, spectroscopic technique typically used to determine vibrational modes of molecules, although rotational and other low-frequency modes of systems may also be observed. Ra ...

came to be based on this phenomenon, and Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

, President of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, referred to it in his presentation of the Hughes Medal

The Hughes Medal is a silver-gilt medal awarded by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. T ...

to Raman in 1930 as "among the best three or four discoveries in experimental physics in the last decade".

Raman was confident that he would win the Nobel Prize in Physics as well but was disappointed when the Nobel Prize went to Owen Richardson in 1928 and to Louis de Broglie

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French theoretical physicist and aristocrat known for his contributions to quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he postulated the wave nature of elec ...

in 1929. He was so confident of winning the prize in 1930 that he booked tickets in July, even though the awards were to be announced in November. He would scan each day's newspaper for announcement of the prize, tossing it away if it did not carry the news. He did eventually win that year.

Later work

Raman had association with theBanaras Hindu University

Banaras Hindu University (BHU), formerly Benares Hindu University, is a collegiate, central, and research university located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, and founded in 1916. The university incorporated the Central Hindu College, ...

in Varanasi

Varanasi (, also Benares, Banaras ) or Kashi, is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tradition of I ...

. He attended the foundation ceremony of BHU and delivered lectures on mathematics and "Some new paths in physics" during the lecture series organised at the university from 5 to 8 February 1916. He also held the position of permanent visiting professor.

With Suri Bhagavantam, he determined the spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spin (physics) or particle spin, a fundamental property of elementary particles

* Spin quantum number, a number which defines the value of a particle's spin

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thr ...

of photons

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that ...

in 1932, which further confirmed the quantum nature of light. With another student, Nagendra Nath, he provided the correct theoretical explanation for the acousto-optic effect (light scattering by sound waves) in a series of articles resulting in the celebrated Raman–Nath theory. Modulators, and switching systems based on this effect have enabled optical communication components based on laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

systems.

Other investigations he carried out included experimental and theoretical studies on the diffraction of light by acoustic waves of ultrasonic and hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds five times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since i ...

frequencies, and those on the effects produced by X-rays on infrared vibrations in crystals exposed to ordinary light which were published between 1935 and 1942.

In 1948, through studying the spectroscopic behaviour of crystals, he approached the fundamental problems of crystal dynamics in a new manner. He dealt with the structure and properties of diamond from 1944 to 1968, the structure and optical behaviour of numerous iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

substances including labradorite

Labradorite (( Ca, Na)( Al, Si)4 O8) is a calcium-enriched feldspar mineral first identified in Labrador, Canada, which can display an iridescent effect ( schiller).

Labradorite is an intermediate to calcic member of the plagioclase series. It ...

, pearly feldspar

Feldspar ( ; sometimes spelled felspar) is a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagiocl ...

, agate

Agate ( ) is a banded variety of chalcedony. Agate stones are characterized by alternating bands of different colored chalcedony and sometimes include macroscopic quartz. They are common in nature and can be found globally in a large number of d ...

, quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

, opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silicon dioxide, silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3% to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6% and 10%. Due to the amorphous (chemical) physical structure, it is classified as a ...

, and pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

in the early 1950s. Among his other interests were the optics of colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s, and electrical and magnetic anisotropy

Anisotropy () is the structural property of non-uniformity in different directions, as opposed to isotropy. An anisotropic object or pattern has properties that differ according to direction of measurement. For example, many materials exhibit ve ...

. His last interests in the 1960s were on biological properties such as the colours of flowers and the physiology of human vision.

Personal life

Raman married Lokasundari Ammal, daughter of S. Krishnaswami Iyer who was the Superintendent of Sea Customs at Madras, in 1907. The wedding day is popularly recorded as on 6 May, but Raman's great-niece and biographer, Uma Parameswaran, revealed a factual date of 2 June 1907. It was a self-arranged marriage and his wife was 13 years old. (Sources are contradicting on her age as her birth year is specified as 1892, which would make her about 15 years of age; but Parameswaran affirmed the 13-year, corroborated by her obituary in '' Current Science'' that mentioned her age as 86 on her death on 22 May 1980.) His wife later jokingly recounted that their marriage was not so much about her musical prowess (she was playing ''veena

The ''veena'', also spelled ''vina'' ( IAST: vīṇā), is any of various chordophone instruments from the Indian subcontinent. Ancient musical instruments evolved into many variations, such as lutes, zithers and arched harps.

'' when they first met) as "the extra allowance which the Finance Department gave to its married officers." The extra allowance refers to an additional INR 150 for married officers at the time. Soon after they moved to Calcutta in 1907, the couple were accused of converting to Christianity. It was because they frequently visited St. John's Church, Kolkata as Lokasundari was fascinated with the church music and Raman with the acoustics.

They had two sons, Chandrasekhar Raman and Venkatraman Radhakrishnan, a radio astronomer. Raman's elder brother Chandrasekhara Subrahmanya Ayyar's son Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (; 19 October 1910 – 21 August 1995) was an Indian Americans, Indian-American theoretical physicist who made significant contributions to the scientific knowledge about the structure of stars, stellar evolution and ...

won the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Throughout his life, Raman developed an extensive personal collection of stones, mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s, and materials with interesting light-scattering properties, which he obtained from his world travels and as gifts. He often carried a small, handheld spectroscope

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

to study specimens. These, along with his spectrograph, are on display at IISc.

Lord Rutherford was instrumental in some of Raman's most pivotal moments in life. He nominated Raman for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930, presented him the Hughes Medal as President of the Royal Society in 1930, and recommended him for the position of Director at IISc in 1932.

Raman had a sense of obsession with the Nobel Prize. In a speech at the University of Calcutta, he said, "I'm not flattered by the honour ellowship to the Royal Society in 1924done to me. This is a small achievement. If there is anything that I aspire for, it is the Nobel Prize. You will find that I get that in five years." He knew that if he were to receive the Nobel Prize, he could not wait for the announcement of the Nobel Committee normally made towards the end of the year considering the time required to reach Sweden by sea route. With confidence, he booked two tickets, one for his wife, for a steamship to Stockholm in July 1930. Soon after he received the Nobel Prize, he was asked in an interview the possible consequences if he had discovered the Raman effect earlier, which he replied, "Then I should have shared the Nobel Prize with Compton and I should not have liked that; I would rather receive the whole of it."

Religious views

Although Raman hardly talked about religion, he was openly anagnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the supernatural is either unknowable in principle or unknown in fact. (page 56 in 1967 edition) It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief and refer to ...

, but objected to being labelled atheist. His agnosticism was largely influenced by that of his father who adhered to the philosophies of Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

, Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Br ...

, and Robert G. Ingersoll

Robert Green Ingersoll (; August 11, 1833 – July 21, 1899), nicknamed "the Great Agnostic", was an American lawyer, writer, and orator during the Golden Age of Free Thought, who campaigned in defense of agnosticism.

Personal life

Robert Inge ...

. He resented Hindu traditional rituals but did not give them up in family circles. He was also influenced by the philosophy of '' Advaita Vedanta''. Traditional ''pagri

Phari or Pagri (; ) is a town in Yadong County in the Tibet Autonomous Region, China near the border with Bhutan. The border can be accessed through a secret road/trail connecting Tsento Gewog in Bhutan () known as Tremo La. the town had a popu ...

'' (Indian turban) with a tuft underneath and a '' upanayana'' (Hindu sacred thread) were his signature attire. Though it was not customary to wear turbans in South Indian culture, he explained his habit as, "Oh, if I did not wear one, my head will swell. You all praise me so much and I need a turban to contain my ego." He even attributed his turban for the recognition he received on his first visit to England, particular from J. J. Thomson and Lord Rutherford. In a public speech, he once said,In a friendly meeting with Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

and Gilbert Rahm, a German zoologist, the conversation turned to religion. Raman spoke,On his deathbed, he said to his wife, "I believe only in the Spirit of Man," and asked for his funeral, "Just a clean and simple cremation for me, no mumbo-jumbo please."

Death

At the end of October 1970, Raman had acardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest (also known as sudden cardiac arrest CA is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. When the heart stops beating, blood cannot properly Circulatory system, circulate around the body and the blood flow to the ...

and collapsed in his laboratory. He was moved to the hospital where doctors diagnosed his condition and declared that he would not survive for another four hours. He however survived a few days and requested to stay in the gardens of his institute surrounded by his followers and fans.

Two days before Raman died, he told one of his former students, "Do not allow the journals of the Academy to die, for they are the sensitive indicators of the quality of science being done in the country and whether science is taking root in it or not." That evening, Raman met with the Board of Management of his institute in his bedroom and discussed with them the fate of the institute's management. He also willed his wife to perform a simple cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

without any rituals upon his death. He died from natural causes early the next morning on 21 November 1970 at the age of 82.

With the news of Raman's death, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

publicly announced, saying,

Controversies

The Nobel Prize

Independent discovery

In 1928,Grigory Landsberg

Grigory Samuilovich Landsberg (Russian: Григорий Самуилович Ландсберг; 22 January 1890 – 2 February 1957) was a Soviet physicist who worked in the fields of optics and spectroscopy. Together with Leonid Mandelstam h ...

and Leonid Mandelstam at the Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

independently discovered the Raman effect. They published their findings in July issue of ''Naturwissenschaften

''The Science of Nature'', formerly ''Naturwissenschaften'', is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media covering all aspects of the natural sciences relating to questions of biological significance. I ...

,'' and presented their findings at the Sixth Congress of the Russian Association of Physicists held at Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

between 5 and 16 August. In 1930, they were nominated for the Nobel Prize alongside Raman. According to the Nobel Committee, however: (1) the Russians did not come to an independent interpretation of their discovery as they cited Raman's article; (2) they observed the effect only in crystals, whereas Raman and Krishnan observed it in solids, liquids and gases, and therefore proved the universal nature of the effect; (3) the problems concerning the intensity of Raman and infrared lines in the spectra had been explained during the previous year; (4) the Raman method had been applied with great success in different fields of molecular physics; and (5) the Raman effect had effectively helped to check the symmetry properties of molecules, and thus the problems concerning nuclear spin in atomic physics.

The Nobel Committee proposed only Raman's name to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

for the Nobel Prize. Evidence later appeared that the Russians had discovered the phenomenon earlier, a week before Raman and Krishnan's discovery. According to Mandelstam's letter (to Orest Khvolson), the Russian had observed the spectral line on 21 February 1928.

Role of Krishnan

Krishnan was not nominated for the Nobel Prize even though he was the main researcher in discovering the Raman effect. He alone first noted the new scattering. Krishnan co-authored all the scientific papers on the discovery in 1928 except two. He alone wrote all the follow-up studies. Krishnan himself never claimed himself worthy of the prize. But Raman admitted later that Krishnan was the co-discoverer. He however remained openly antagonistic towards Krishnan, which the latter described as "the greatest tragedy of my life." After Krishnan's death, Raman said to a correspondent from ''The Times of India

''The Times of India'' (''TOI'') is an Indian English-language daily newspaper and digital news media owned and managed by the Times Group. It is the List of newspapers in India by circulation, third-largest newspaper in India by circulation an ...

'', "Krishnan was the greatest charlatan I have known, and all his life he masqueraded in the cloak of another man's discovery."

The Raman–Born controversy

From October 1933 to March 1934,Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

was employed by IISc as Reader in Theoretical Physics following the invitation by Raman early in 1933. Born at the time was a refugee from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and temporarily employed at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

. Since the beginning of the 20th century Born had developed a theory on lattice dynamics based on thermal properties. He presented his theory in one of his lectures at IISc. By then Raman had developed a different theory and claimed that Born's theory contradicted the experimental data. Their debate lasted for decades.

In this dispute, Born received support from most physicists, as his view was proven to be a better explanation. Raman's theory was generally regarded as having partial relevance. Beyond the intellectual debate, their rivalry extended to personal and social levels. Born later said that Raman probably thought of him as an "enemy." Despite the mounting evidence for Born's theory, Raman refused to concede. As the editor of ''Current Science'' he rejected articles that supported Born's theory. Born was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize specifically for his contributions to lattice theory, and eventually won it for his statistical works on quantum mechanics in 1954. The account was written as a "belated Nobel Prize."

Indian authorities

Raman had an aversion to the thenPrime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen Union Council of Ministers, Council of Ministers, despite the president of ...

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

and Nehru's policies on science. In one instance he smashed the bust of Nehru on the floor. In another, he shattered his Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ) is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distin ...

medallion to pieces with a hammer, as it was given to him by the Nehru government. He publicly ridiculed Nehru when the latter visited the Raman Research Institute in 1948. There they displayed a piece of gold and copper against an ultraviolet light. Nehru was tricked into believing that copper which glowed more brilliantly than any other metal was gold. Raman was quick to remark, "Mr Prime Minister, everything that glitters is not gold."

On the same occasion Nehru, offered Raman financial assistance to his institute which Raman flatly refused by replying, "I certainly don't want this to become another government laboratory." Raman was particularly against the control of research programmes by the government such as in the establishment of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre

The Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) is India's premier nuclear research facility, headquartered in Trombay, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was founded by Homi Jehangir Bhabha as the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET) in January 1954 ...

(BARC), Defence Research and Development Organisation

The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) is an agency under the Department of Defence Research and Development in the Ministry of Defence of the Government of India, charged with the military's research and development, head ...

(DRDO), and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research

The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR; IAST: ''vaigyanik tathā audyogik anusandhāna pariṣada'') is a research and development (R&D) organisation in India to promote scientific, industrial and economic growth. Headquarter ...

(CSIR). He remained hostile to people associated with these establishments including Homi J. Bhabha

Homi Jehangir Bhabha, FNI, FASc, FRS (30 October 1909 – 24 January 1966) was an Indian nuclear physicist who is widely credited as the "father of the Indian nuclear programme". He was the founding director and professor of physics at the ...

, S.S. Bhatnagar, and his once favourite student, Krishnan. He even called such programmes as the "Nehru–Bhatnagar effect." In 1959, Raman proposed to establish another research institute in Madras. The Government of Madras advised him to apply for funds from the central government. But Raman clearly foresaw as he replied to C. Subramaniam, then the Minister for Finance Education in Madras, that his proposal to Nehru's government "would be met with a refusal." So ended the plan.

Raman described AICC authorities as "a big ''tamasha''" (drama or spectacle) that just kept on discussing issues without action. As to problems of food resources in India, his advice to the government was, "We must stop breeding like pigs and the matter will solve itself."

Indian Academy of Sciences

The Indian Academy of Sciences was born out of conflicts during the procedures of the proposal for a national scientific organization in line with the Royal Society. In 1933, the Indian Science Congress Association (ISCA), at the time the largest scientific organization, planned to establish a national science body, which would be authorized to advise the government on scientific matters. Sir Richard Gregory, then editor of ''Nature,'' on his visit to India had suggested Raman, as editor of ''Current Science'', to establish an Indian Academy of Sciences. Raman thought that it should be an exclusively Indian membership as opposed to the general consensus that British members should be included. He resolved "How can India Science prosper under the tutelage of an academy which has its own council of 30, 15 of who are Britishers of whom only two or three are fit enough to be its Fellows." On 1 April 1933, he convened a separate meeting of the South Indian scientists. He and Subba Rao officially resigned from ISCA. Raman registered the new organization as the Indian Academy of Sciences on 24 April to the Registrar of Societies. It was a provisional name to be changed to the Royal Society of India after approval from theRoyal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

. The Government of India did not recognize it as an official national scientific body, as such the ICSA created a separate organization named the National Institute of Sciences of India on 7 January 1935 (but again changed to the Indian National Science Academy

The Indian National Science Academy (INSA) is a national academy in New Delhi

New Delhi (; ) is the Capital city, capital of India and a part of the Delhi, National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three b ...

in 1970). INSA had been led by the foremost rivals of Raman including Meghnad Saha

Meghnad Saha (6 October 1893 – 16 February 1956) was an Indian astrophysicist and politician who helped devise the theory of Thermal ionization, thermal ionisation. His Saha ionization equation, Saha ionisation equation allowed astronomers to ...

, Bhabha, Bhatnagar, and Krishnan.

Indian Institute of Science

Raman had a great fallout with the authorities at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). He was accused of biased development in physics while ignoring other fields. He lacked diplomatic personality with other colleagues, which S. Ramaseshan, his nephew and later Director of IISc, reminisced, saying, "Raman went in there like a bull in a china shop." He wanted research in physics at the level of those of western institutes, but at the expense of other fields of science.Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

observed, "Raman found a sleepy place where very little work was being done by a number of extremely well–paid people." At the Council meeting, Kenneth Aston, professor in the Electrical Technology Department, harshly criticized Raman and Raman's recruitment of Born. Raman had every intention of giving the full position of professor to Born. Aston even made a personal attack on Born by referring to him as someone "who was rejected by his own country, a renegade and therefore a second-rate scientist unfit to be part of the faculty, much less to be the head of the department of physics."

The Council of IISc constituted a review committee to oversee Raman's conduct in January 1936. The committee, chaired by James Irvine, Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

, reported in March that Raman had misused the funds and entirely shifted the "centre of gravity" towards research in physics, and also that the proposal of Born as Professor of Mathematical Physics (which was already approved by the Council in November 1935) was not financially feasible. The Council offered Raman two choices, either to resign from the institute with effect from 1 April or resign as the Director and continue as Professor of physics; if he did not make the choice, he was to be fired. Raman was inclined to take up the second choice.

The Royal Society