Britain's Early Neolithic Period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The  The Neolithic also saw the construction of a wide variety of monuments in the landscape, many of which were

The Neolithic also saw the construction of a wide variety of monuments in the landscape, many of which were

Until recently, archaeologists debated whether the Neolithic Revolution was brought to the British Isles through adoption by natives or by migrating groups of Continental Europeans who settled there.

A 2019 study found that the Neolithic farmers of the British Isles had entered the region through a mass migration c. 4100 BC. They were closely related to Neolithic peoples of Iberia, which implies that they were descended from agriculturalists who had moved westwards from the Balkans along the Mediterranean coast. The arrival of farming populations led to the almost-complete replacement of the native

Until recently, archaeologists debated whether the Neolithic Revolution was brought to the British Isles through adoption by natives or by migrating groups of Continental Europeans who settled there.

A 2019 study found that the Neolithic farmers of the British Isles had entered the region through a mass migration c. 4100 BC. They were closely related to Neolithic peoples of Iberia, which implies that they were descended from agriculturalists who had moved westwards from the Balkans along the Mediterranean coast. The arrival of farming populations led to the almost-complete replacement of the native

The reason for switching from a hunter-gatherer to an agricultural lifestyle has been widely debated by archaeologists and anthropologists. Ethnographic studies of farming societies who use basic stone tools and crops have shown that it is a much more labour-intensive way of life than that of hunter-gatherers. It would have involved deforesting an area, digging and tilling the soil, storing seeds, and then guarding the growing crops from other animal species before eventually harvesting them. In the cases of grains, the crop produced then has to be processed to make it edible, including grinding, milling and cooking. All of that involves far more preparation and work than either hunting or gathering.

The reason for switching from a hunter-gatherer to an agricultural lifestyle has been widely debated by archaeologists and anthropologists. Ethnographic studies of farming societies who use basic stone tools and crops have shown that it is a much more labour-intensive way of life than that of hunter-gatherers. It would have involved deforesting an area, digging and tilling the soil, storing seeds, and then guarding the growing crops from other animal species before eventually harvesting them. In the cases of grains, the crop produced then has to be processed to make it edible, including grinding, milling and cooking. All of that involves far more preparation and work than either hunting or gathering.

The Neolithic agriculturalists

The Neolithic agriculturalists

The Early and the Middle Neolithic also saw the construction of large

The Early and the Middle Neolithic also saw the construction of large

File:Towriepetrosphere.jpg, Carved stone ball from Towie, Scotland, c. 3200 BC

File:Folkton DrumsSCF6613.jpg,

The term "Neolithic" was first coined by the archaeologist

The term "Neolithic" was first coined by the archaeologist

File:Skara Brae, inside a Neolithic house - geograph.org.uk - 2764846.jpg, Reconstructed house interior at Skara Brae

File:Arthur's stone, near Swansea.jpeg, Maen Ceti (arthur stone) burial site, Gower, Wales.

File:BrynCelliDdu3.jpg,

Godmanchester's Temple of the Sun - Ancient Europe's most sophisticated astronomical computer (New Scientist 1991)

{{Prehistoric technology Neolithic Europe Stone Age Britain History of the British Isles 5th-millennium BC establishments

The

The Neolithic period

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wid ...

in the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

lasted from 4100 to 2,500 BC. Constituting the final stage of the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

in the region, it was preceded by the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

and followed by the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

.

During the Mesolithic period, the inhabitants of the British Isles had been hunter-gatherers. Around 4000 BC, migrants began arriving from Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. These migrants brought new ideas, leading to a radical transformation of society and landscape that has been called the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

. The Neolithic period in the British Isles was characterised by the adoption of agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

and sedentary living. To make room for the new farmland, the early agricultural communities undertook mass deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

across the islands, which dramatically and permanently transformed the landscape. At the same time, new types of stone tools requiring more skill began to be produced, and new technologies included polishing. Although the earliest indisputably-acknowledged languages spoken in the British Isles belonged to the Celtic branch of the Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

family, it is not known what language the early farming people spoke.

The Neolithic also saw the construction of a wide variety of monuments in the landscape, many of which were

The Neolithic also saw the construction of a wide variety of monuments in the landscape, many of which were megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging geographically f ...

ic in nature. The earliest of them are the chambered tomb

A chambered cairn is a burial monument, usually constructed during the Neolithic British Isles, Neolithic, consisting of a sizeable (usually stone) chamber around and over which a cairn of stones was constructed. Some chambered cairns are also pas ...

s of the Early Neolithic, but in the Late Neolithic, this form of monumentalization was replaced by the construction of stone circles

A stone circle is a ring of megalithic standing stones. Most are found in Northwestern Europe – especially Stone circles in the British Isles and Brittany – and typically date from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, with most being bu ...

, a trend that would continue into the following Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. Those constructions are taken to reflect ideological changes, with new ideas about religion, ritual and social hierarchy.

The Neolithic people in Europe were not literate and so they left behind no written record that modern historians can study. All that is known about this time period in Europe comes from archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

investigations. These were begun by the antiquarians

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic sit ...

of the 18th century and intensified in the 19th century during which John Lubbock coined the term "Neolithic". In the 20th and the 21st centuries, further excavation and synthesis went ahead, dominated by figures like V. Gordon Childe

Vere Gordon Childe (14 April 189219 October 1957) was an Australian archaeologist who specialised in the study of European prehistory. He spent most of his life in the United Kingdom, working as an academic for the University of Edinburgh and ...

, Stuart Piggott

Stuart Ernest Piggott, (28 May 1910 – 23 September 1996) was a British archaeologist, best known for his work on prehistoric Wessex.

Early life

Piggott was born in Petersfield, Hampshire, the son of G. H. O. Piggott, and was educated ...

, Julian Thomas

Julian Stewart Thomas (born 1959) is a British archaeologist, publishing on the Neolithic and Bronze Age prehistory of Britain and north-west Europe. Thomas has been vice president of the Royal Anthropological Institute since 2007. He has been P ...

and Richard Bradley.

Historical overview

Late Mesolithic

The period that preceded the Neolithic in the British Isles is known by archaeologists as theMesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

. During the early part of that period, Britain was still attached by the landmass of Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

to the rest of Continental Europe.

The archaeologist and prehistorian Caroline Malone noted that during the Late Mesolithic, the British Isles were something of a "technological backwater" in European terms and were still living as a hunter-gatherer society though most of Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

had already taken up agriculture and sedentary living.

Early and Middle Neolithic: 4000–2900 BC

Spread of Neolithic

Between 10,000 BC to 8,000 BC the Neolithic Revolution in the Near East gradually transformed hunter-gathering societies into settled agricultural societies. Similar developments later occurred independently inMesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

, Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. It was in the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

that the "most important developments in early farming" occurred in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

and the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

, which stretched through what are now parts of Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, areas that already had rich ecological variation, which was being exploited by hunter-gatherers in the Late Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic periods.

Early signs of these hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s beginning to harvest, manipulate and grow various food plants have been identified in the Mesolithic Natufian culture

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

of the Levant, which showed signs that would later lead to the actual domestication and farming of crops. Archaeologists believe that the Levantine peoples subsequently developed agriculture in response to a rise in their population levels that could not be fed by the finite food resources that hunting and gathering could provide. The idea of agriculture subsequently spread from the Levant into Europe and was adopted by hunter-gathering societies in what is now Turkey, Greece, the Balkans and across the Mediterranean and eventually reached north-western Europe and the British Isles.

The Neolithic in the British Isles

Until recently, archaeologists debated whether the Neolithic Revolution was brought to the British Isles through adoption by natives or by migrating groups of Continental Europeans who settled there.

A 2019 study found that the Neolithic farmers of the British Isles had entered the region through a mass migration c. 4100 BC. They were closely related to Neolithic peoples of Iberia, which implies that they were descended from agriculturalists who had moved westwards from the Balkans along the Mediterranean coast. The arrival of farming populations led to the almost-complete replacement of the native

Until recently, archaeologists debated whether the Neolithic Revolution was brought to the British Isles through adoption by natives or by migrating groups of Continental Europeans who settled there.

A 2019 study found that the Neolithic farmers of the British Isles had entered the region through a mass migration c. 4100 BC. They were closely related to Neolithic peoples of Iberia, which implies that they were descended from agriculturalists who had moved westwards from the Balkans along the Mediterranean coast. The arrival of farming populations led to the almost-complete replacement of the native Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

hunter-gatherers of the British Isles, who did not experience a genetic resurgence in the succeeding centuries.

The 2003 discovery of the Ness of Brodgar

The Ness of Brodgar is a Neolithic archaeological site covering located between the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness in the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site on Mainland, Orkney, Scotland. Excavations took place from ...

site has presented an example of a highly-sophisticated and possibly-religious complex in the British Isles dating from around 3500 BC, before the first pyramids

A pyramid () is a Nonbuilding structure, structure whose visible surfaces are triangular in broad outline and converge toward the top, making the appearance roughly a Pyramid (geometry), pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid ca ...

and contemporary with the city of Uruk

Uruk, the archeological site known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river in Muthanna Governorate, Iraq. The site lies 93 kilo ...

. The site is still in early stages of excavation but is expected to yield major contributions to knowledge of the period.

Late Neolithic: 3000–2500 BC

* Meldon Bridge Period

End of the Neolithic

From theBeaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell Beaker (archaeology), beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, ...

period onwards, all British individuals had high proportions of Steppe ancestry

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the start of the 5th millennium B ...

and were genetically more similar to Beaker-associated people from the Lower Rhine area. Beakers arrived in Britain around 2500 BC, with migrations of Yamnaya

The Yamnaya ( ) or Yamna culture ( ), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–C ...

-related people, resulting in a nearly-total turnover of the British population. The study argues that more than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the coming of the Beaker people.

Characteristics

Agriculture

The Neolithic is largely categorised by the introduction offarming

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

to Britain from Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

from where it had originally come from the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. Until then, during the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods, the island's inhabitants had been hunter-gatherers

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially w ...

, and the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural one did not occur all at once. There is also some evidence of different agricultural and hunter-gatherer groups within the British Isles meeting and trading with one another in the early part of the Neolithic, with some hunter-gatherer sites showing evidence of more complex, Neolithic technologies. Archaeologists disagree about whether the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural society was gradual, over a period of centuries, or rapid, accomplished within a century or two. The process of the introduction of agriculture is still not fully understood, and as the archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson

Michael Parker Pearson, (born 26 June 1957) is an English archaeologist specialising in the study of the Neolithic British Isles, Madagascar and the archaeology of death and burial. A professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, he prev ...

noted:

The reason for switching from a hunter-gatherer to an agricultural lifestyle has been widely debated by archaeologists and anthropologists. Ethnographic studies of farming societies who use basic stone tools and crops have shown that it is a much more labour-intensive way of life than that of hunter-gatherers. It would have involved deforesting an area, digging and tilling the soil, storing seeds, and then guarding the growing crops from other animal species before eventually harvesting them. In the cases of grains, the crop produced then has to be processed to make it edible, including grinding, milling and cooking. All of that involves far more preparation and work than either hunting or gathering.

The reason for switching from a hunter-gatherer to an agricultural lifestyle has been widely debated by archaeologists and anthropologists. Ethnographic studies of farming societies who use basic stone tools and crops have shown that it is a much more labour-intensive way of life than that of hunter-gatherers. It would have involved deforesting an area, digging and tilling the soil, storing seeds, and then guarding the growing crops from other animal species before eventually harvesting them. In the cases of grains, the crop produced then has to be processed to make it edible, including grinding, milling and cooking. All of that involves far more preparation and work than either hunting or gathering.

Deforestation

The Neolithic agriculturalists

The Neolithic agriculturalists deforested

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

areas of woodland in the British Isles to use the cleared land for farming. Notable examples of forest clearance occurred around 5000 BCE in Broome Heath in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

, on the North Yorkshire Moors

The North York Moors is an upland area in north-eastern Yorkshire, England. It contains one of the largest expanses of heather moorland in the United Kingdom. The area was designated as a National Park in 1952, through the National Parks and A ...

and also on Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, South West England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite that forms the uplands dates from the Carb ...

. Such clearances were performed not only with the use of stone axes but also through ring barking

Girdling, also called ring-barking, is the circumferential removal or injury of the bark (consisting of cork cambium or "phellogen", phloem, cambium and sometimes also the xylem) of a branch or trunk of a woody plant. Girdling prevents the tree ...

and burning, with the last two likely having been more effective. Nonetheless, in many areas, the forests had regrown within a few centuries, including at Ballysculion, Ballynagilly, Beaghmore and the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south ...

.

Between 4300 and 3250 BCE, there was a widespread decline in the number of elm trees across Britain, with millions of them disappearing from the archaeological record, and archaeologists have in some cases attributed that to the arrival of Neolithic farmers. For instance, it has been suggested that farmers collected all the elm leaves to use as animal fodder during the winter and that the trees died after being debarked by domesticated cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

. Nonetheless, as Pearson highlighted, the decline in elm might be due to the elm bark beetle Elm bark beetle is a common name for several insects and may refer to:

*''Hylurgopinus rufipes'', native to North America

*''Scolytus multistriatus

''Scolytus multistriatus'', the European elm bark beetle or smaller European elm bark beetle, is ...

, a parasitic insect that carries with it Dutch elm disease, and evidence for which has been found at West Heath Spa in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

. It is possible that the spread of those beetles was coincidental although the hypothesis has also been suggested that farmers intentionally spread the beetles so that they destroyed the elm forests to provide more deforested land for farming.

Meanwhile, from around 3500 to 3300 BCE, many of those deforested areas began to see reforestation and mass tree regrowth, indicating that human activity had retreated from those areas.

Settlement

Around the period between 3500 and 3300 BC, agricultural communities had begun centring themselves upon the most productive areas, where the soils were more fertile, namely around the Boyne,Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, eastern Scotland, Anglesey

Anglesey ( ; ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms the bulk of the Principal areas of Wales, county known as the Isle of Anglesey, which also includes Holy Island, Anglesey, Holy Island () and some islets and Skerry, sker ...

, the upper Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

, Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

, Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

and the river valleys of The Wash

The Wash is a shallow natural rectangular bay and multiple estuary on the east coast of England in the United Kingdom. It is an inlet of the North Sea and is the largest multiple estuary system in the UK, as well as being the largest natural ba ...

. Those areas saw an intensification of agricultural production and larger settlements.

The Neolithic houses of the British Isles were typically rectangular and made out of wood and so none had survived to this day. Nonetheless, foundations of such buildings have been found in the archaeological record although they are rare and have usually been uncovered only when they were in the vicinity of the more substantial Neolithic stone monuments.

Monumental architecture

Chambered tombs

The Early and the Middle Neolithic also saw the construction of large

The Early and the Middle Neolithic also saw the construction of large megalithic

A megalith is a large Rock (geology), stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging ...

tombs across the British Isles. Because they housed the bodies of the dead, those tombs have typically been considered by archaeologists to be a possible indication of ancestor veneration

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

by those who constructed them. Such Neolithic tombs are common across much of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, from Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

to Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, and they were therefore likely brought to the British Isles along with or roughly concurrent to the introduction of farming. A widely-held theory amongst archaeologists is that those megalithic tombs were intentionally made to resemble the long timber houses, which had been constructed by Neolithic farming peoples in the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

basin from circa 4800 BC.

As the historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an Indian-born English historian specialising in early modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion, and modern paganism. A professor at the University of Bristol, Hutton has writte ...

related, "There is no doubt that these great tombs, far more impressive than would be required of mere repositories for bones, were the centres of ritual activity in the early Neolithic: they were shrines as well as mausoleums. For some reason, the success of farming and the veneration of ancestral and more recent bones had become bound up together in the minds of the people".

Although there are disputed radiocarbon dates

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

indicating that the chambered tomb at Carrowmore

Carrowmore (, 'the great quarter') is a large group of megalithic monuments on the Coolera Peninsula to the west of Sligo, Ireland. They were built in the 4th millennium BC, during the Neolithic (New Stone Age). There are 30 surviving tombs wi ...

in Ireland dates to circa 5000 BCE, the majority of such monuments in the British Isles appear to have been built between 4000 and 3200 BC, a time period that the archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson

Michael Parker Pearson, (born 26 June 1957) is an English archaeologist specialising in the study of the Neolithic British Isles, Madagascar and the archaeology of death and burial. A professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, he prev ...

notes means that tomb building was "a relatively short-lived fashion in archaeological terms".

Stone circles

The Late Neolithic also saw the construction ofmegalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging geographically f ...

ic stone circles.

Society and culture

Stone technology

The stone or "lithic" technology of the British Neolithic differed from that of Mesolithic and Palaeolithic Britain. Whereas Mesolithic hunter-gatherer tools weremicroliths

A microlith is a small Rock (geology), stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 60,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Austral ...

(small, sharp shards of flint), Neolithic agriculturalists used larger lithic tools. Typically, they included axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

s, made out of either flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

or hard igneous rock

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

hafted on to wooden handles. While some of them were evidently used for chopping wood and other practical purposes, there are some axe heads from the period that appear never to have been used, some being too fragile to have been used in any case. The latter axes most likely had a decorative or ceremonial function.

Settlement

Neolithic Britons were capable of building a variety of different wooden constructions. For instance, in the marshland of theSomerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south ...

in south-western Britain, a wooden trackway was built in the winter of 3807 BC and connected the Polden Hills

The Polden Hills in Somerset, England, are a long, low ridge, extending for , and separated from the Mendip Hills, to which they are nearly parallel, by a marshy tract known as the Somerset Levels. They are now bisected at their western end by ...

with Westhay Mears, a length which ran for over a kilometre.

Diet

Being agriculturalists, the Neolithic peoples of the British Isles grewcereal

A cereal is a grass cultivated for its edible grain. Cereals are the world's largest crops, and are therefore staple foods. They include rice, wheat, rye, oats, barley, millet, and maize ( Corn). Edible grains from other plant families, ...

grains such as wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

and barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, which therefore played a part in their diet. Nonetheless, they were supplemented at times with wild undomesticated plant foods such as hazelnuts

The hazelnut is the nut (fruit), fruit of the hazel, hazel tree and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus ''Corylus'', especially the nuts of the species ''Corylus avellana''. They are also known as cobnuts or fil ...

.

There is also evidence that grapes

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

had been consumed in Neolithic Wessex, based upon charred pips found at the site of Hambledon Hill. They may have been imported from Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

, or they might have been grown on British soil, as the climate was warmer than that of the early 21st century.

Religion

As the archaeologist John C. Barrett noted, "There never was a single body of beliefs which characterise 'neolithic religion'... The variety of practices attested by he various Neolithicmonuments cannot be explained as the expression of a single, underlying cultural idea".Folkton Drums

The Folkton Drums are a very rare set of three decorated chalk objects in the shape of Drum (container), drums or solid cylinders dating from the Neolithic Europe, Neolithic period. Found in a child's grave near the village of Folkton in northe ...

, England, c. 2600 BC

File:Chalk Drum .(photo courtesy of British Museum).jpg, Burton Agnes drum

The Burton Agnes drum is a carved chalk cylinder dated from 3005 to 2890 BC which was found in 2015 near Burton Agnes, East Riding of Yorkshire, England. The British Museum has described it as "the most important piece of prehistoric art ...

, England, c. 3000 BC

File:NMW - Keulenkopf.jpg, Macehead, Wales, 3000–2500 BC

File:Neolithic ornaments.png, Stone armring and callaïs jewellery

File:Knowth - 48051048418.jpg, Engraved 'calendar stone' at Knowth

Knowth (; ) is a prehistoric tomb overlooking the River Boyne in County Meath, Ireland. It comprises a large passage tomb surrounded by 17 smaller tombs, built during the Neolithic era around 3200 BC. It contains the largest assemblage of megali ...

File:Kelvingrove Art Gallery and MuseumDSCF0239 11.JPG, Carved stone balls, Scotland

File:British Museum jadeite axe.jpg, Jade axe, England, c. 3000 BC

File:Chiselled granite basin at Newgrange.jpg, Chiselled granite basin, Newgrange

Newgrange () is a prehistoric monument in County Meath in Ireland, placed on a rise overlooking the River Boyne, west of the town of Drogheda. It is an exceptionally grand passage tomb built during the Neolithic Period, around 3100 BC, makin ...

File:Knowth-stone-basin.jpg, Stone bowl, Knowth

File:Newgrange Phallic Stone - Kevin Lawver.jpg, Carved stone from Newgrange

File:Westray Wife 20110529.jpg, The 'Westray Wife

The Westray Wife (also known as the Orkney Venus) is a small Neolithic figurine, in height, carved from sandstone. It was discovered during an Historic Scotland dig at the Links of Noltland, on Westray, Orkney, Scotland, in the summer of 2009. ...

' from Orkney

File:Macehead1.jpg, Polished stone macehead, England, c. 2900 BC

File:Knowth 20.jpg, Macehead from Knowth

File:Symbols of Skara Brae.jpg, Inscribed symbols from Skara Brae

Skara Brae is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill in the parish of Sandwick, Orkney, Sandwick, on the west coast of Mainland, Orkney, Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consiste ...

File:Clanfield, Neolithic longhouse (geograph 5420533).jpg, Neolithic house reconstruction at Butser Farm

File:Horton House, Butser Ancient Farm.jpg, Neolithic house, 3800 BC, reconstruction at Butser Farm

File:Knap of Howar - geograph.org.uk - 1398054.jpg, Knap of Howar

The Knap of Howar () on the island of Papa Westray in Orkney, Scotland is a Neolithic farmstead which may be the oldest preserved stone house in northern Europe. Radiocarbon dating shows that it was occupied from 3700 BC to 2800 BC, earlier than ...

, Orkney, Scotland, 3700–2800 BC

Antiquarian and archaeological investigations

17th and 18th centuries

It was in the 17th century AD that scholarly investigation into the surviving Neolithic monuments first began in the British Isles, but at the time, theseantiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

scholars had relatively little understanding of prehistory and were Biblical literalists

Biblical literalism or biblicism is a term used differently by different authors concerning biblical interpretation. It can equate to the dictionary definition of literalism: "adherence to the exact letter or the literal sense", where literal me ...

, who believed that the Earth itself was only around 5000 years old.

The first to do so was the antiquary and writer John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He was a pioneer archaeologist, who recorded (often for the first time) numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England ...

(1626–1697), who had been born into a wealthy gentry family before he went on to study at Trinity College, Oxford

Trinity College (full name: The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the foundation of Sir Thomas Pope (Knight)) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in E ...

, until his education was disrupted by the outbreak of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

between Royalist and Parliamentarian forces. He recorded his accounts of the megalithic monuments in a book, the ''Monumenta Britannica'', but it remained unpublished.

Nonetheless, Aubrey's work was picked up by another antiquarian in the following century, William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

(1687–1765), who had studied at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College (full name: "The College of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary", often shortened to "Corpus") is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. From the late 14th c ...

before he became a professional doctor.

19th century

The term "Neolithic" was first coined by the archaeologist

The term "Neolithic" was first coined by the archaeologist John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury

John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury (30 April 1834 – 28 May 1913), known as Sir John Lubbock, 4th Baronet, from 1865 until 1900, was an English banker, Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician, philanthropist, scientist and polymath. Lubbock worked ...

, in his 1865 book ''Pre-historic times, as illustrated by ancient remains, and the manners and customs of modern savages''. He used it to refer to the final stage of the Stone Age and defined this period purely on the technology of the time, when humans had begun using polished stone tools but not yet started making metal tools. Lubbock's terminology was adopted by other archaeologists, but as they gained a greater understanding of later prehistory, it came to cover a wider set of characteristics. By the 20th century, when figures like V. Gordon Childe were working on the British Neolithic, the term "Neolithic" had been broadened to "include sedentary village life, cereal agriculture, stock rearing, and ceramics, all assumed characteristic of immigrant agriculturalists".

20th and 21st centuries

In the 1960s, a number of British and American archaeologists began taking a new approach to their discipline by emphasising their belief that through the rigorous use of thescientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

, they could obtain objective knowledge about the human past. In doing so, they forged the theoretical school of processual archaeology

Processual archaeology (formerly, the New Archaeology) is a form of archaeological theory. It had its beginnings in 1958 with the work of Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips, ''Method and Theory in American Archaeology,'' in which the pair stated ...

. The processual archaeologists took a particular interest in the ecological impact on human society, and in doing so, the definition of "Neolithic" was "narrowed again to refer just to the agricultural mode of subsistence".

In the late 1980s, processualism began to come under increasing criticism by a new wave of archaeologists, who believed in the innate subjectivity of the discipline. The figures forged the new theoretical school of post-processual archaeology

Post-processual archaeology, which is sometimes alternatively referred to as the interpretative archaeologies by its adherents, is a movement in archaeological theory that emphasizes the subjectivity of archaeological interpretations. Despite havin ...

, and a number of post-processualists turned their attention to the Neolithic British Isles. They interpreted the Neolithic as an ideological phenomenon that was adopted by British, Irish and Manx society and led to them creating new forms of material-culture, such as the megalithic funerary and ceremonial monuments.

Gallery

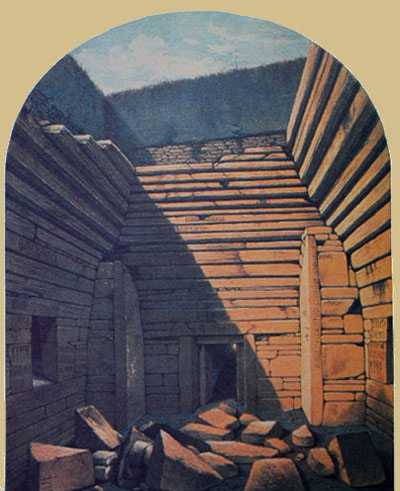

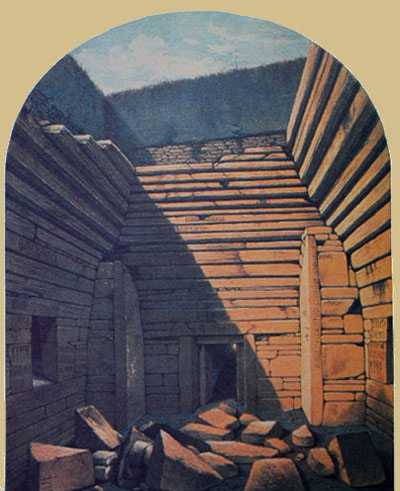

Bryn Celli Ddu

Bryn Celli Ddu () is a prehistoric site on the Wales, Welsh island of Anglesey located near Llanddaniel Fab. Its Welsh placenames, name means 'the mound in the dark grove'. It was archaeologically excavated between 1928 and 1929. Visitors can ge ...

, Wales

File:Sweet track.jpg, Part of the Sweet Track

The Sweet Track is an ancient trackway, or causeway, in the Somerset Levels, England, named after its finder, Ray Sweet. It was built in 3807 BC (determined using dendrochronology – tree-ring dating) and is the second-oldest timber track ...

oak causeway, England, c. 3800 BC

File:Reconstruction of the Sweet Track.jpg, Reconstruction of the Sweet Track

File:2019-06-07 06-22 Irland 134 Brú na Bóinne, Knowth, Megalithic Tombs.jpg, Knowth

Knowth (; ) is a prehistoric tomb overlooking the River Boyne in County Meath, Ireland. It comprises a large passage tomb surrounded by 17 smaller tombs, built during the Neolithic era around 3200 BC. It contains the largest assemblage of megali ...

interior passage

File:Roundhouses Stonehenge Visitors Centre.jpg, Reconstructed buildings at Stonehenge

File:UlsterMuseumPrehistoryNeo (2).JPG, Model of a Neolithic house, Ireland

File:Callanish Stones in summer 2012 (7).JPG, Callanish stones

The Calanais Stones (or "Calanais I": or ) are an arrangement of menhir, standing stones placed in a cruciform pattern with a central stone circle, located on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. They were erected in the late Neolithic British Isles, Ne ...

, Scotland

File:Avebury Stone Circles.jpg, Avebury

Avebury () is a Neolithic henge monument containing three stone circles, around the village of Avebury in Wiltshire, in south-west England. One of the best-known prehistoric sites in Britain, it contains the largest megalithic stone circle in ...

, England

File:Barnhouse settlement1.jpg, The Barnhouse Settlement

The Neolithic Barnhouse Settlement is sited by the shore of Loch of Harray, Orkney Mainland, Scotland, not far from the Standing Stones of Stenness, about 5 miles north-east of Stromness.

It was discovered in 1984 by Colin Richards. Excavation ...

, Orkney

References

Bibliography

Academic and popular books

* * * * * * * * *Academic papers and articles

* * * * * *Other articles

* *External links

Godmanchester's Temple of the Sun - Ancient Europe's most sophisticated astronomical computer (New Scientist 1991)

{{Prehistoric technology Neolithic Europe Stone Age Britain History of the British Isles 5th-millennium BC establishments