Bowling Green, Manhattan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bowling Green is a small, historic, public park in the

On July 9, 1776, after the

On July 9, 1776, after the

The park is a teardrop-shaped plaza formed by the branching of Broadway as it nears

The park is a teardrop-shaped plaza formed by the branching of Broadway as it nears

"Bull!"

, article, September 1, 2007, ''The Tribeca Trib'', retrieved June 13, 2009 and a "Wall Street icon". In 2017, another bronze sculpture, '' Fearless Girl'', was installed across from the bull. Designed by sculptor

Richard B. Marrin, "Harbor History: Bowling Green: The Birthplace of New York"

{{Authority control Broadway (Manhattan) Parks on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan Urban public parks Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register in New York (state)

Financial District

A financial district is usually a central area in a city where financial services firms such as banks, insurance companies, and other related finance corporations have their headquarters offices. In major cities, financial districts often host ...

of Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan, also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York City, is the southernmost part of the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of Manhattan. The neighborhood is History of New York City, the historical birthplace o ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, at the southern end and address origin of Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

. Located in the 18th century next to the site of the original Dutch fort of New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

, it served as a public gathering place and under the English was designated as a park in 1733. It is the oldest public park in New York City and is surrounded by its original 18th-century cast iron fence. The park included an actual bowling green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

and a monumental equestrian statue of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

prior to the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Pulled down in 1776, the 4000-pound statue is said to have been melted for ammunition to fight the British.

Bowling Green is adjacent to another historic park, the Battery, located to the southwest. It is surrounded by several buildings, including the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House (with the NYC office of the National Archives

National archives are the archives of a country. The concept evolved in various nations at the dawn of modernity based on the impact of nationalism upon bureaucratic processes of paperwork retention.

Conceptual development

From the Middle Ages i ...

), the International Mercantile Marine Company Building

1 Broadway (formerly known as the International Mercantile Marine Company Building, the United States Lines Building, and the Washington Building) is a 12-story office building in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City. It is locate ...

, Bowling Green Offices Building, Cunard Building

The Cunard Building is a Grade II* listed building in Liverpool, England. It is located at the Pier Head and along with the neighbouring Royal Liver Building and Port of Liverpool Building is one of Liverpool's ''Three Graces'', which line the ...

, 26 Broadway

26 Broadway, also known as the Standard Oil Building or Socony–Vacuum Building, is an office building adjacent to Bowling Green in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The 31-story, structure was designed in the Renais ...

, and 2 Broadway. The ''Charging Bull

''Charging Bull'' (sometimes referred to as the ''Bull of Wall Street'' or the ''Bowling Green Bull'') is a bronze sculpture that stands on Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway just north of Bowling Green (New York City), Bowling Green in the Financ ...

'' sculpture is located on the northern end of the park. The park is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

under the name Bowling Green Fence and Park. It is also a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, an NRHP district created in 2007.

History

Lenape site

Bowling Green was a significant cultural site before European colonization. There may have been a residence for the chief of a localLenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

Native American tribe at the southern end of the Wickquasgeck trail (modern-day Broadway). There was also a large elm at the end of the trail, where the trail split. It is likely at Bowling Green that the Dutch Governor Peter Minuit

Peter Minuit (French language, French: ''Pierre Minuit'', Dutch language, Dutch: ''Peter Minnewit''; 1580 – August 5, 1638) was a Walloons, Walloon merchant and politician who was the 3rd Director of New Netherland, Director of the Dutch Nort ...

purchased Manhattan for $24 worth of merchandise in 1626.

Colonial era

The park has long been a center of activity in the city, going back to colonialNew Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

, when it served as a cattle market between 1638 and 1647, and a parade ground

A parade is a procession of people, usually organized along a street, often in costume, and often accompanied by marching bands, floats, or sometimes large balloons. Parades are held for a wide range of reasons, but are usually some variety ...

. In 1675, the city's Common Council designated the "plaine afore the forte" for an annual market of "graine, cattle and other produce of the country". In 1677, the city's first public well was dug in front of Fort Amsterdam

Fort Amsterdam, (later, Fort George among other names) was a fortification on the southern tip of Manhattan Island at the confluence of the Hudson River, Hudson and East River, East rivers in what is now New York City. The fort and the island ...

at Bowling Green. In 1733, the Common Council leased a portion of the parade grounds to three prominent neighboring landlords for a peppercorn

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter (f ...

a year, upon their promise to create a park that would be "the delight of the Inhabitants of the City" and add to its "Beauty and Ornament"; the improvements were to include a "bowling green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

" with "walks therein". The surrounding streets were not paved with cobblestones

Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings. Setts, also called ''Belgian blocks'', are often referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct from a ...

until 1744.

On August 21, 1770, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

government erected a gilded lead equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

in Bowling Green; the King was dressed in Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

garb in the style of the ''Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (; ) is an ancient Roman art, ancient Roman equestrian statue on the Capitoline Hill, Rome, Italy. It is made of bronze and stands 4.24 m (13.9 ft) tall. Although the emperor is mounted, the sculptur ...

''. The statue had been commissioned in 1766, along with a statue of William Pitt, from the prominent London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

sculptor Joseph Wilton

Joseph Wilton (16 July 1722 – 25 November 1803) was an English sculptor. He was one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1768, and the academy's third keeper.

His works are particularly numerous memorialising the famous Britons ...

, as a celebration of victory after the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. With the rapid deterioration of relations with the mother country after 1770, the statue became a magnet for the Bowling Green protests.On November 1, 1765, the Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It p ...

, protesting the Stamp Act, had marched down Broadway carrying an effigy of the Royal Governor. They threw rocks and bricks at the adjacent Fort George, and at Bowling Green they burned the Governor's effigy as well as his coach, which had fallen into their hands. In 1773, the city passed an anti-graffiti

Graffiti (singular ''graffiti'', or ''graffito'' only in graffiti archeology) is writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from simple written "monikers" to elabor ...

and anti-desecration

Desecration is the act of depriving something of its sacred character, or the disrespectful, contemptuous, or destructive treatment of that which is held to be sacred or holy by a group or individual.

Overview

Many consider acts of desecration t ...

law to counter vandalism against the monument, and a protective cast-iron fence was built along the perimeter of the park; the fence is still extant, making it the city's oldest fence.

On July 9, 1776, after the

On July 9, 1776, after the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

was read to Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

's troops at the current site of City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

, local Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It p ...

rushed down Broadway to Bowling Green to topple the statue of King George III; in the process, finial

A finial () or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the Apex (geometry), apex of a dome, spire, tower, roo ...

s on the tops of the fence depicting the royal symbol of a crown were sawed off. The event is one of the most enduring images in the city's history. According to folklore, the statue was chopped up and shipped to a Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

foundry under the direction of Oliver Wolcott

Oliver Wolcott Sr. ( ; November 20, 1726 December 1, 1797) was an American Founding Father and politician. He was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation as a representative of Connecticut, ...

to be made into 42,088 patriot bullets at 20 bullets per pound (2,104.4 pounds). The statue's head was to have been paraded about town on pike-staffs but was recovered by Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

and sent to England. Eight pieces of the lead statue are preserved at the New-York Historical Society

The New York Historical (known as the New-York Historical Society from 1804 to 2024) is an American history museum and library on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. The society was founded in 1804 as New York's first museum. It ...

, one is in the Museum of the City of New York

The Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) is a history and art museum in Manhattan, New York City, New York. It was founded by Henry Collins Brown, in 1923Beard, Rick. "Museum of the City of New York" in to preserve and present the history ...

, and one is in Connecticut. (estimated total of 260–270 pounds); In 1991 the left hand and forearm of the statue was found in Wilton Connecticut; likewise 9 lead musket balls from the Monmouth Battlefield had the same lead content as the statue The stone slab on which the statue rested was used as a gravestone before becoming part of the collection of the New-York Historical Society; the stone pedestal itself remained until it was torn down. The event has been depicted over the years in several works of art, including an 1854 painting by William Walcutt, and an 1859 painting by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel.

On November 25, 1783, a U.S. soldier managed to rip down the British flag at Bowling Green and replace it with the Stars and Stripes—an apparently difficult feat, since the British had greased the flagpole. As the defeated British military boarded ships back to England, then-General George Washington triumphantly led the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

through Manhattan down to Bowling Green to witness the last British troops sailing away from Lower Manhattan.

Postcolonial era

The marble slab of the statue's pedestal was first used as the tombstone of a Major John Smith of theBlack Watch

The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland (3 SCOTS) is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. The regiment was created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881, when the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment ...

, who died in 1783 and was buried at a burial ground across the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

at Paulus Hook

Paulus Hook is a community on the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City, New Jersey. It is located across the river from Manhattan. The name Hook comes from the Dutch word "hoeck", which translates to "point of land." This "point of land" has ...

in what is now Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, second-most populous

. When Smith's grave site was leveled in 1804, the slab became a stone step at two successive mansions in Jersey City. The latter was the Van Vorst Mansion that was owned by Cornelius Van Vorst

Cornelius Van Vorst (March 7, 1822 – November 19, 1906) was the twelfth Mayor of Jersey City, serving from 1860 to 1862.

Biography

Cornelius and his family founded and laid out the street grid for Van Vorst Township, which was incorporated in ...

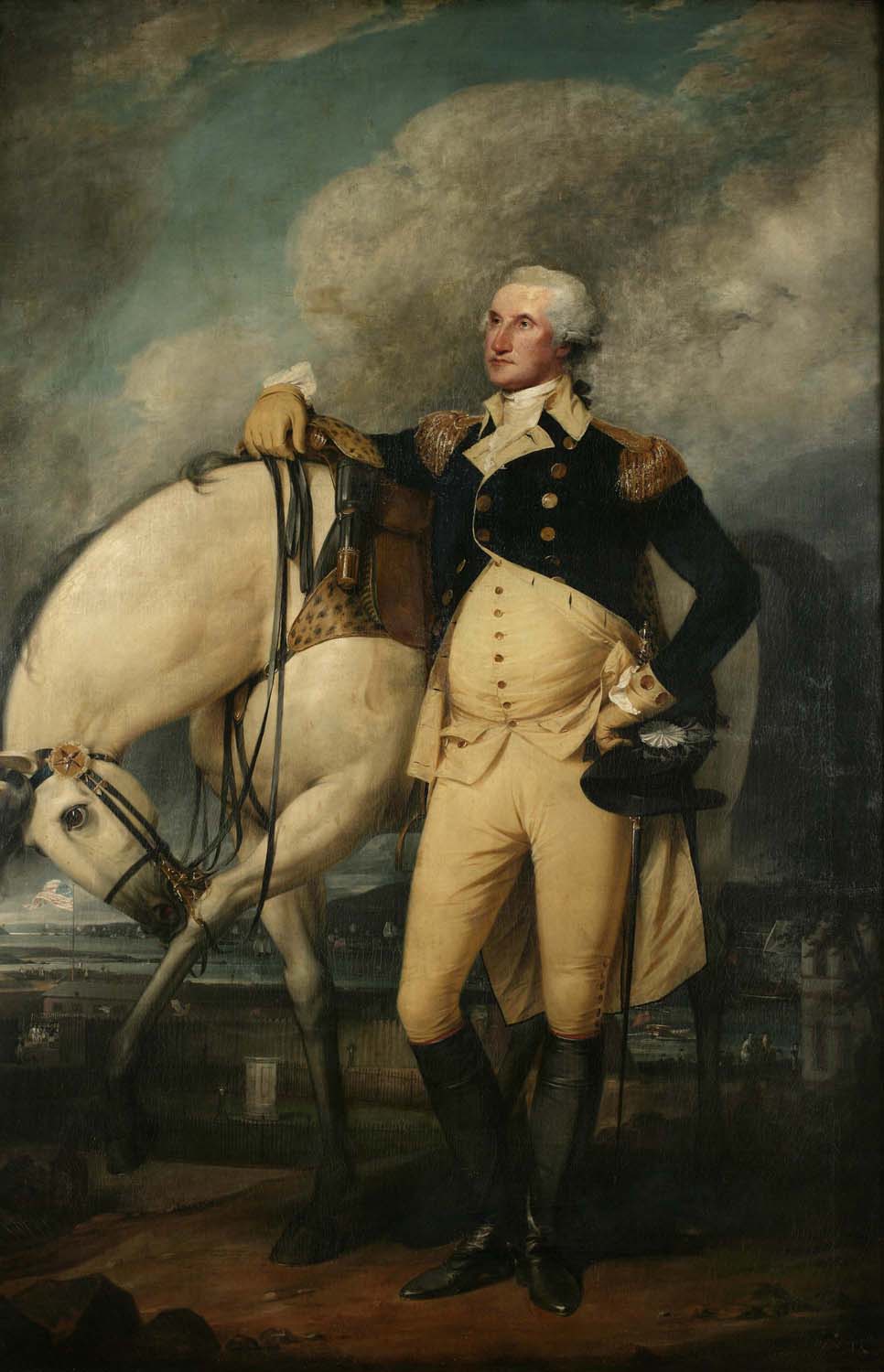

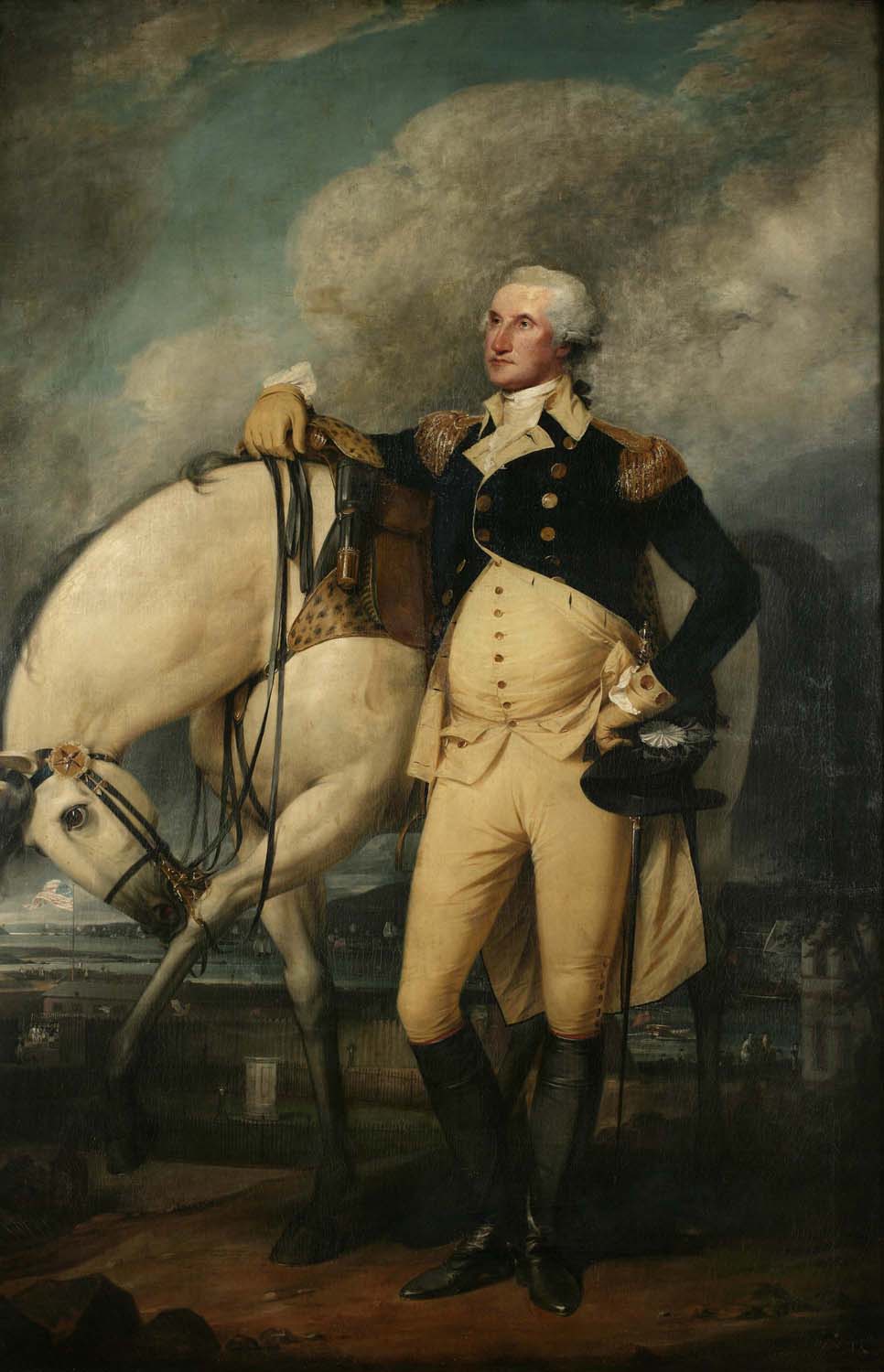

where the stone remained from 1854 to 1874. In 1880 the inscription was rediscovered, and the slab was transferred to the New-York Historical Society. The monument base can be seen in the background of the portrait of George Washington painted by John Trumbull

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756 – November 10, 1843) was an American painter and military officer best known for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called the "Painter of the Revolut ...

in 1790, now sited in City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

. The William Pitt statue is in the New-York Historical Society.

Following the Revolution, the remains of Fort Amsterdam facing Bowling Green were demolished in 1790 and part of the rubble used to extend Battery Park to the west. In its place a grand Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and British Overseas Territories. The name is also used in some other countries.

Government Houses in th ...

was built, suitable, it was hoped, for a president's house, with a four-columned portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

facing across Bowling Green and up Broadway. Governor John Jay later inhabited it. When the state capital was moved to Albany, the building served as a boarding house and then the custom house

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

before being demolished in 1815.Eric Homberger, ''Mrs. Astor's New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age'' 2004 Elegant townhouses were built around the park which remained largely the private domain of the residents, though now some of the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

of New York were replaced by Republican ones; leading New York merchants, led by Abraham Kennedy, in a mansion at 1 Broadway that had a facade under a central pediment and a front towards the Battery Parade, as the new piece of open ground was called. The Hon. John Watts, whose summer place was Rose Hill Rose Hill may refer to:

People

* Rose Hill (actress) (1914–2003), British actress

* Rose Hill (athlete) (born 1956), British wheelchair athlete

Film

* ''Rose Hill'' (film), a 1997 movie

Places Australia

* Rose Hill, New South Wales

* Rose ...

; Chancellor Robert Livingston at number 5, Stephen Whitney

Stephen Whitney (September 4, 1776 – February 16, 1860) was an American merchant. He was one of the wealthiest merchants in New York City in the first half of the 19th century. His fortune was considered second only to that of John Jacob Ast ...

at number 7, and John Stevens all constructed brick residences in Federal style

Federal-style architecture is the name for the classical architecture built in the United States following the American Revolution between 1780 and 1830, and particularly from 1785 to 1815, which was influenced heavily by the works of And ...

facing Bowling Green. The Alexander Macomb House

The Alexander Macomb House at 39–41 Broadway in Lower Manhattan, New York City, served as the second U.S. Presidential Mansion. President George Washington occupied it from February 23 to August 30, 1790, during New York City's two-year term ...

, the second Presidential Mansion, stood north of the park at 39–41 Broadway. President George Washington occupied it from February 23 to August 30, 1790, before the U.S. capital was moved to Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

.

In 1825, Bowling Green Park was "laid down in grass". At the time, it was an ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focus (geometry), focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special ty ...

with a diameter of on the north–south axis and on the east–west axis. By 1850, with the opening of Lafayette Street

Lafayette Street ( ) is a major north–south street in Lower Manhattan, New York City. It originates at the intersection of Reade Street and Centre Street, one block north of Chambers Street. The one-way street then successively runs throu ...

and the subsequent completions of Washington Square Park

Washington Square Park is a public park in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City. It is an icon as well as a meeting place and center for cultural activity. The park is operated by the New York City Department o ...

and Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

, the general northward migration of residences in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

led to the conversion of the residences into shipping offices, resulting in full public access to the park.

20th and 21st centuries

The park was described in 1926 as having "walks, benches,sumac

Sumac or sumach ( , )—not to be confused with poison sumac—is any of the roughly 35 species of flowering plants in the genus ''Rhus'' (and related genera) of the cashew and mango tree family, Anacardiaceae. However, it is '' Rhus coriaria ...

trees and poorly-kept '' ic' lawns", as well as a fountain in the center used by local children to cool off in the summer. It suffered neglect after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Starting in 1972, the city renovated Bowling Green to restore its 17th-century character. In conjunction with the park's renovation, the Bowling Green subway station underneath the park was expanded, necessitating the temporary excavation of the park. The renovation faced a lack of funds during the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis

It was also declared the ''International Women's Year'' by the United Nations and the European Architectural Heritage Year by the Council of Europe.

Events

January

* January 1 – Watergate scandal (United States): John N. Mitchell, H. R. ...

but was completed in the late 1970s.

The Bowling Green Fence and Park were listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

in 1980. In 1982, the Irish Institute of New York installed a plaque in the park commemorating an important religious liberty challenge which occurred in colonial Manhattan in 1707, when Reverend Francis Makemie

Francis Makemie (1658–1708) was an Ulster Scots clergyman, widely regarded as the founder of Presbyterianism in the United States.

Early and family life

Makemie was born in Ramelton, County Donegal, Ireland part of the province of Ulster. ...

, the founder of American Presbyterianism, preached at a home near the park in defiance of the orders of Lord Cornbury, and was subsequently arrested, charged with preaching a "pernicious doctrine", and later acquitted.

In 1989, the sculpture ''Charging Bull

''Charging Bull'' (sometimes referred to as the ''Bull of Wall Street'' or the ''Bowling Green Bull'') is a bronze sculpture that stands on Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway just north of Bowling Green (New York City), Bowling Green in the Financ ...

'' by Arturo Di Modica

Arturo Di Modica (January 26, 1941February 19, 2021) was an Italian sculptor, widely known for his ''Charging Bull'' sculpture.

English sculptor Henry Moore nicknamed Di Modica “the young Michelangelo” after they met in Italy in the 1960s. ...

was installed at the northern tip of the park by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, also called the Parks Department or NYC Parks, is the department of the government of New York City responsible for maintaining the city's parks system, preserving and maintaining the ecolog ...

after it had been confiscated by the police following its illegal installation on Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

. The sculpture has become one of the most popular and recognizable landmarks of the Financial District. In March 2017, Bowling Green was co-named Evacuation Day Plaza, which was marked by the erection of an illuminated street sign, commemorating the location of a pivotal event in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

that ended a seven-year occupation by British troops.

Description and surroundings

The park is a teardrop-shaped plaza formed by the branching of Broadway as it nears

The park is a teardrop-shaped plaza formed by the branching of Broadway as it nears Whitehall Street

Whitehall Street is a street in the South Ferry (Manhattan), South Ferry/Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City, near the southern tip of Manhattan Island. The street begins at Bowling ...

. It has a fenced-in grassy area with a large fountain in the center, surrounded by benches that are popular at lunchtime with workers from the nearby Financial District

A financial district is usually a central area in a city where financial services firms such as banks, insurance companies, and other related finance corporations have their headquarters offices. In major cities, financial districts often host ...

.

The south end of the plaza is bounded by the front entrance of the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, which houses the George Gustav Heye Center

The National Museum of the American Indian–New York, the George Gustav Heye Center, is a branch of the National Museum of the American Indian at the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in Manhattan, New York City. The museum is part of the Sm ...

for the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

's National Museum of the American Indian

The National Museum of the American Indian is a museum in the United States devoted to the culture of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. It is part of the Smithsonian Institution group of museums and research centers.

The museum has three ...

and the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York is the United States bankruptcy court within the Southern District of New York. The Southern District of New York is a major venue for bankruptcy, as it has jurisdiction o ...

(Manhattan Division). Previously there was a public street along the south edge of the park, also called "Bowling Green", but since this area was needed for a modern entrance to the park's eponymous subway station, the road was eliminated and paved over with cobblestones. The New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system in New York City serving the New York City boroughs, boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. It is owned by the government of New York City and leased to the New York City Tr ...

station on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line

The IRT Lexington Avenue Line (also known as the IRT East Side Line and the IRT Lexington–Fourth Avenue Line) is one of the lines of the A Division (New York City Subway), A Division of the New York City Subway, stretching from Lower Manhatt ...

, opened in 1905 and serving the , is located under the plaza. Entrances dating from both 1905 and more recent renovations are located in and near the plaza.

The urban value of the space is created by the skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Most modern sources define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition, other than being very tall high-rise bui ...

s and other structures that surround it (listed clockwise from the south):

* Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House

* International Mercantile Marine Company Building

1 Broadway (formerly known as the International Mercantile Marine Company Building, the United States Lines Building, and the Washington Building) is a 12-story office building in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City. It is locate ...

, 1 Broadway (1882–1884, Edward H. Kendall; expanded 1921, Walter B. Chambers

Walter Boughton Chambers, American Institute of Architects, AIA (September 15, 1866 – April 19, 1945) was a successful New York City architect whose buildings continue to be landmarks in the city's skyline and whose contributions to archite ...

), the United States Lines-Panama Pacific Line

Panama Pacific Line was a subsidiary of International Mercantile Marine (IMM) established to carry passengers and freight between the US East Coast of the United States, East and West Coast of the United States, West Coasts via the Panama Canal.

H ...

Building

* Bowling Green Offices Building, 11 Broadway (1895–1898, W. and G. Audsley, later serving the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping line. Founded out of the remains of a defunct Packet trade, packet company, it gradually grew to become one of the most prominent shipping companies in the world, providing passenger and cargo service ...

)

* Cunard Building

The Cunard Building is a Grade II* listed building in Liverpool, England. It is located at the Pier Head and along with the neighbouring Royal Liver Building and Port of Liverpool Building is one of Liverpool's ''Three Graces'', which line the ...

, 25 Broadway (1921, Benjamin Wistar Morris, with Carrère and Hastings

Carrère and Hastings, the firm of John Merven Carrère ( ; November 9, 1858 – March 1, 1911) and Thomas Hastings (architect), Thomas Hastings (March 11, 1860 – October 22, 1929), was an American list of architecture firms, architecture firm ...

)

* 26 Broadway

26 Broadway, also known as the Standard Oil Building or Socony–Vacuum Building, is an office building adjacent to Bowling Green in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The 31-story, structure was designed in the Renais ...

, the Standard Oil Company Building, on the east side of Broadway, facing the Cunard Building (1922, Carrère and Hastings

Carrère and Hastings, the firm of John Merven Carrère ( ; November 9, 1858 – March 1, 1911) and Thomas Hastings (architect), Thomas Hastings (March 11, 1860 – October 22, 1929), was an American list of architecture firms, architecture firm ...

with Shreve, Lamb & Blake)

* 2 Broadway (1959–1960, Emery Roth & Sons

Emery Roth (, died August 20, 1948) was a Hungarian-American architect of Hungarian-Jewish descent who designed many New York City hotels and apartment buildings of the 1920s and 1930s, incorporating Beaux-Arts and Art Deco details. His sons co ...

, resurfaced in 1999 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

SOM, an initialism of its original name Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, is a Chicago-based architectural, urban planning, and engineering firm. It was founded in 1936 by Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings. In 1939, they were joined by engineer ...

), a Modernist glass wall that replaced the distinguished Produce Exchange Building (1881–1884, George B. Post

George Browne Post (December15, 1837November28, 1913) was an American architect trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition. Active from 1869 almost until his death, he was recognized as a master of several contemporary American architectural genres, an ...

), as an "acceptable sacrifice" intended to spur financial district rebuilding

Fence

The fence surrounding Bowling Green Park was erected in 1773 to protect the equestrian statue of King George III. It still stands as the oldest fence in New York City. The fence was originally designed by Richard Sharpe, Peter T. Curtenius, Gilbert Forbes, and Andrew Lyall, and was erected at a cost of 843 New York pounds (£562 sterling). It is made ofwrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

on a stone base. Each fence post once had a finial

A finial () or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the Apex (geometry), apex of a dome, spire, tower, roo ...

at its top, which in turn was once adorned with lamps.

The cast-iron finials on the fence were sawed off on July 9, 1776, the day that the United States Declaration of Independence reached New York. The finials were restored in 1786; the saw marks remain visible today. In 1791, the fence and stone base were raised by . The fence was relocated to Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

between 1914 and 1919 to make way for the construction of the Bowling Green subway station. It was repaired again during the park's 1970s renovation. The fence was designated an official city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is the Government of New York City, New York City agency charged with administering the city's Historic preservation, Landmarks Preservation Law. The LPC is responsible for protecting Ne ...

in 1970.

Sculptures

''Charging Bull

''Charging Bull'' (sometimes referred to as the ''Bull of Wall Street'' or the ''Bowling Green Bull'') is a bronze sculpture that stands on Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway just north of Bowling Green (New York City), Bowling Green in the Financ ...

'', a bronze sculpture

Bronze is the most popular metal for Casting (metalworking), cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply "a bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as w ...

in Bowling Green, designed by Arturo Di Modica and installed in 1989, stands tall and measures long. The oversize sculpture depicts a bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

, the symbol of aggressive financial optimism and prosperity, leaning back on its haunches with its head lowered as if ready to charge. The sculpture is a popular tourist destination drawing thousands of people a day, as well as "one of the most iconic images of New York",Pinto Nick"Bull!"

, article, September 1, 2007, ''The Tribeca Trib'', retrieved June 13, 2009 and a "Wall Street icon". In 2017, another bronze sculpture, '' Fearless Girl'', was installed across from the bull. Designed by sculptor

Kristen Visbal

Kristen Visbal (born December 3, 1962) is an American sculptor living and working in Lewes, Delaware. She specializes in lost-wax casting in bronze.

Biography

Visbal was born in Montevideo, Uruguay, the daughter of American Ralph Albert and El ...

, the work was hailed for its feminist message. The ''Fearless Girl'' statue, commissioned by State Street Global Advisors

State Street Global Advisors (SSGA) is an American investment management division of State Street Corporation founded in 1978 and the world's fourth largest asset manager, with nearly in assets under management as of December 31, 2023. SSGA ...

as a way to call attention to the gender pay gap

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are Employment, employed. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct measurements of the pay gap: non ...

and a lack of women on corporate financial sector boards, was installed on March 7, 2017. The statue depicts a defiant little girl posing as an affront to and staring down ''Charging Bull''. The statue was initially scheduled to be removed April 2, 2017, but was later allowed to remain in place through February 2018. The statue was removed in November 2018 and relocated to a site facing the New York Stock Exchange Building

The New York Stock Exchange Building (also NYSE Building) is the headquarters of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), located in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It is composed of two co ...

.

On May 29, 2017, artist Alex Gardega added a statue of a small dog, titled ''Pissing Pug'' (alternatively ''Peeing Pug'' or ''Sketchy Dog''), but he removed it after approximately three hours. He described the ''Fearless Girl'' statue as "corporate nonsense" and "disrespect to the artist that made the bull".

References

Notes CitationsExternal links

Richard B. Marrin, "Harbor History: Bowling Green: The Birthplace of New York"

{{Authority control Broadway (Manhattan) Parks on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan Urban public parks Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register in New York (state)