Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Symphony No. 9 in

Although the performance was officially conducted by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's

Although the performance was officially conducted by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's

'' ''O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!' Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen, und freudenvollere''.'' ("Oh friends, not these sounds! Let us instead strike up more pleasing and more joyful ones!").

At about 25 minutes in length, the finale is the longest of the four movements. Indeed, it is longer than several entire symphonies composed during the

The text is largely taken from

The text is largely taken from

Many later composers of the

Many later composers of the

Japan makes Beethoven's Ninth No. 1 for the holidays

, ''

Uranaka, Taiga,

Beethoven concert to fete students' wartime sendoff

, ''The Japan Times'', 1 December 1999, retrieved on 24 December 2010. It was introduced to Japan during World War I by German prisoners held at the Bandō prisoner-of-war camp. Japanese orchestras, notably the

Review

by Philip Hensher, ''

"All Men Become Brothers: The Decades-Long Struggle for Beethoven's Ninth Symphony"

Schiller Institute, June, 2015. * Taruskin, Richard, "Resisting the Ninth", in his ''Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance'' (Oxford University Press, 1995). *Wegner, Sascha (2018). ''Symphonien aus dem Geiste der Vokalmusik : Zur Finalgestaltung in der Symphonik im 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhundert''. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

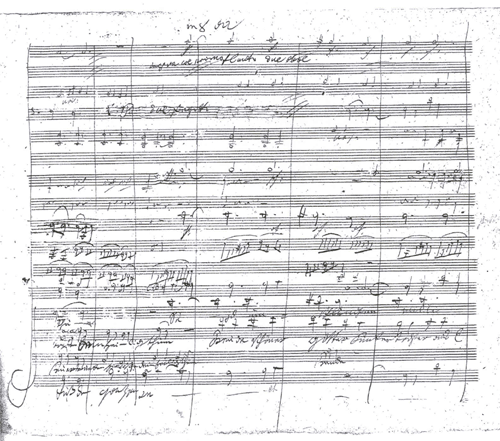

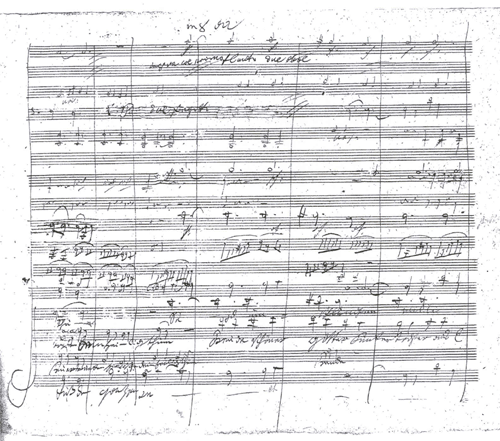

Original manuscript

(site in German)

William and Gayle Cook Music Library,

Text/libretto, with translation, in English and German

* Sources for the metronome marks. Analysis

Analysis for students

(with timings) of the final movement, at

"The Riddle of Beethoven's Alla Marcia in his Ninth Symphony"

(self-published)

Beethoven 9

Benjamin Zander advocating a stricter adherence to Beethoven's metronome indications, with reference to Jonathan del Mar's research (before the Bärenreiter edition was published) and to Stravinsky's intuition about the correct tempo for the Scherzo Trio Audio

Christoph Eschenbach conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra

from

Felix Weingartner conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1935 recording)

from the

Otto Klemperer conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra (1956 live recording)

from the

Official EU page

about the anthem

Program note

by

''Following the Ninth: In the Footsteps of Beethoven's Final Symphony''

Kerry Candaele's 2013 documentary film about the Ninth Symphony {{Authority control 09 Beethoven 9 Choral compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven Works commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society Music dedicated to nobility or royalty 1824 compositions Musical settings of poems by Friedrich Schiller Memory of the World Register Compositions in D minor Frederick William III of Prussia

D minor

D minor is a minor scale based on D, consisting of the pitches D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. Its key signature has one flat. Its relative major is F major and its parallel major is D major.

The D natural minor scale is:

Changes needed ...

, Op. 125, is a choral symphony

A choral symphony is a musical composition for orchestra, choir, and sometimes solo (music), solo vocalists that, in its internal workings and overall musical architecture, adheres broadly to symphony, symphonic musical form. The term "choral s ...

, the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musicologists as a masterpiece

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

of Western classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be #Relationship to other music traditions, distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical mu ...

and one of the supreme achievements in the history of music. One of the best-known works in common practice music, it stands as one of the most frequently performed symphonies in the world.

The Ninth was the first example of a major composer scoring vocal parts in a symphony.Bonds, Mark Evan, "Symphony: II. The 19th century", ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language '' Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and t ...

'', 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols. , 24:837. The final (4th) movement of the symphony, commonly known as the Ode to Joy, features four vocal soloists and a chorus

Chorus may refer to:

Music

* Chorus (song), the part of a song that is repeated several times, usually after each verse

* Chorus effect, the perception of similar sounds from multiple sources as a single, richer sound

* Chorus form, song in whic ...

in the parallel key

In music theory, a major scale and a minor scale that have the same starting note ( tonic) are called parallel keys and are said to be in a parallel relationship. Forte, Allen (1979). ''Tonal Harmony'', p.9. 3rd edition. Holt, Rinehart, and Wi ...

of D major

D major is a major scale based on D (musical note), D, consisting of the pitches D, E (musical note), E, F♯ (musical note), F, G (musical note), G, A (musical note), A, B (musical note), B, and C♯ (musical note), C. Its key signature has two S ...

. The text was adapted from the " An die Freude (Ode to Joy)", a poem written by Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

in 1785 and revised in 1803, with additional text written by Beethoven. In the 20th century, an instrumental arrangement of the chorus was adopted by the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

, and later the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, as the Anthem of Europe

The Anthem of Europe or European Anthem, also known as Ode to Joy, is a piece of instrumental music adapted from the prelude of the final movement of Beethoven's 9th Symphony composed in 1823, originally set to words adapted from Friedric ...

.

In 2001, Beethoven's original, hand-written manuscript of the score, held by the Berlin State Library

The Berlin State Library (; officially abbreviated as ''SBB'', colloquially ''Stabi'') is a universal library in Berlin, Germany, and a property of the German public cultural organization the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation ().

Founded in ...

, was added to the Memory of the World Programme Heritage list established by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, becoming the first musical score so designated.

History

Composition

The Philharmonic Society of London originally commissioned the symphony in 1817. Beethoven made preliminary sketches for the work later that year with the key set as D minor and vocal participation also forecast. The main composition work was done between autumn, 1822 and the completion of the autograph in February, 1824. The symphony emerged from other pieces by Beethoven that, while completed works in their own right, are also in some sense forerunners of the future symphony. The ''Choral Fantasy'', Op. 80, composed in 1808, basically an extendedpiano concerto

A piano concerto, a type of concerto, is a solo composition in the classical music genre which is composed for piano accompanied by an orchestra or other large ensemble. Piano concertos are typically virtuosic showpieces which require an advance ...

movement, brings in a choir and vocal soloists for the climax. The vocal forces sing a theme first played instrumentally, and this theme is reminiscent of the corresponding theme in the Ninth Symphony.

Going further back, an earlier version of the Choral Fantasy theme is found in the song " Gegenliebe" ("Returned Love") for piano and high voice, which dates from before 1795. According to Robert W. Gutman, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

's Offertory in D minor, "Misericordias Domini", K. 222, written in 1775, contains a melody that foreshadows "Ode to Joy".

Premiere

Although most of Beethoven's major works had been premiered in Vienna, the composer planned to have his latest compositions performed in Berlin as soon as possible, as he believed he had fallen out of favor with the Viennese and the current musical taste was now dominated by Italian operatic composers such asRossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano p ...

. When his friends and financiers learned of this, they pleaded with Beethoven to hold the concert in Vienna, in the form of a petition signed by a number of prominent Viennese music patrons and performers.

Beethoven, flattered by the adoration of the Viennese, premiered the Ninth Symphony on 7 May 1824 in the Theater am Kärntnertor

or (Duchy of Carinthia, Carinthian Gate Theatre) was a prestigious theatre in Vienna during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its official title was (Imperial and Royal Court Theatre of Vienna).

History

The theatre was built in 170 ...

in Vienna along with the overture '' The Consecration of the House'' () and three parts (Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei) of the ''Missa solemnis

is Latin for Solemn Mass.Mass

, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. N.p., Appleton, 1910. 797. and is a genre of < ...

''. This was Beethoven's first onstage appearance since 1812 and the hall was packed with an eager and curious audience with a number of noted musicians and figures in Vienna including , ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. N.p., Appleton, 1910. 797. and is a genre of < ...

Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

, Carl Czerny, and the Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

.

The premiere of the Ninth Symphony involved an orchestra nearly twice as large as usual and required the combined efforts of the Kärntnertor house orchestra, the Vienna Music Society ( Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde), and a select group of capable amateurs. While no complete list of premiere performers exists, many of Vienna's most elite performers are known to have participated.

The soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hertz, Hz to A5 in Choir, choral ...

and alto

The musical term alto, meaning "high" in Italian (Latin: '' altus''), historically refers to the contrapuntal part higher than the tenor and its associated vocal range. In four-part voice leading alto is the second-highest part, sung in ch ...

parts were sung by two famous young singers of the day, both recruited personally by Beethoven: Henriette Sontag

Henriette Sontag, born Gertrude Walpurgis Sontag, and, after her marriage, entitled Henriette, Countess Rossi (3 January 1806 – 17 June 1854), was a German operatic soprano of great international renown. She possessed a sweet-toned, lyrical voi ...

and Caroline Unger. German soprano Henriette Sontag was 18 years old when Beethoven asked her to perform in the premiere of the Ninth. 20-year-old contralto

A contralto () is a classical music, classical female singing human voice, voice whose vocal range is the lowest of their voice type, voice types.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare, similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to ...

Caroline Unger, a native of Vienna, had gained critical praise in 1821 appearing in Rossini's ''Tancredi

''Tancredi'' is a ''melodramma eroico'' (''opera seria'' or heroic opera) in two acts by composer Gioachino Rossini and librettist Gaetano Rossi (who was also to write ''Semiramide'' ten years later), based on Voltaire's play ''Tancrède (traged ...

''. After performing in Beethoven's 1824 premiere, Unger then found fame in Italy and Paris. Italian opera composers Bellini and Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian Romantic composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the ''bel canto'' opera ...

were known to have written roles specifically for her voice. Anton Haizinger and Joseph Seipelt sang the tenor

A tenor is a type of male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. Composers typically write music for this voice in the range from the second B below m ...

and bass

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Wood

* Bass or basswood, the wood of the tilia americana tree

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in th ...

/baritone

A baritone is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the bass (voice type), bass and the tenor voice type, voice-types. It is the most common male voice. The term originates from the ...

parts, respectively.

Although the performance was officially conducted by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's

Although the performance was officially conducted by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's Kapellmeister

( , , ), from German (chapel) and (master), literally "master of the chapel choir", designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term has evolved considerably in i ...

, Beethoven shared the stage with him. Because two years earlier, Umlauf had watched as the composer's attempt to conduct a dress rehearsal

The dress rehearsal is a full-scale rehearsal shortly before the first performance where the actors and/or musicians perform every detail of the performance. Dress rehearsal is often the final rehearsal before the premiere

A premiere, also ...

for a revision of his opera ''Fidelio

''Fidelio'' (; ), originally titled ' (''Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love''), Opus number, Op. 72, is the sole opera by German composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of ...

'' ended in disaster, Umlauf instructed the singers and musicians to ignore the almost completely deaf composer. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. He was turning the pages of his score and beating time for an orchestra he could not hear.

There are a number of anecdotes concerning the premiere of the Ninth. Based on the testimony of some of the participants, there are suggestions that the symphony was under-rehearsed (there were only two complete rehearsals) and somewhat uneven in execution. On the other hand, the premiere was a great success. In any case, Beethoven was not to blame, as violinist Joseph Böhm recalled:

Beethoven himself conducted, that is, he stood in front of a conductor's stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts. – The actual direction was in ouisDuport's hands; we musicians followed his baton only.Reportedly, the

scherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often r ...

was completely interrupted at one point by applause. Either at the end of the scherzo or the end of the symphony (testimonies differ), Beethoven was several bars off and still conducting; the contralto Caroline Unger walked over and gently turned Beethoven around to accept the audience's cheers and applause. According to the critic for the ''Theater-Zeitung'', "the public received the musical hero with the utmost respect and sympathy, listened to his wonderful, gigantic creations with the most absorbed attention and broke out in jubilant applause, often during sections, and repeatedly at the end of them." The audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and raised hands, so that Beethoven, who they knew could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovations.

Editions

The first German edition was printed by B. Schott's Söhne (Mainz) in 1826. TheBreitkopf & Härtel

Breitkopf & Härtel () is a German Music publisher, music publishing house. Founded in 1719 in Leipzig by Bernhard Christoph Breitkopf, it is the world's oldest music publisher.

Overview

The catalogue contains over 1,000 composers, 8,000 works ...

edition dating from 1864 has been used widely by orchestras. In 1997, Bärenreiter

Bärenreiter (Bärenreiter-Verlag) is a German classical music publishing house based in Kassel. The firm was founded by Karl Vötterle (1903–1975) in Augsburg in 1923, and moved to Kassel in 1927, where it still has its headquarters; it ...

published an edition by Jonathan Del Mar. According to Del Mar, this edition corrects nearly 3,000 mistakes in the Breitkopf edition, some of which were "remarkable". David Levy, however, criticized this edition, saying that it could create "quite possibly false" traditions. Breitkopf also published a new edition by Peter Hauschild in 2005.

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra. These are by far the largest forces needed for any Beethoven symphony; at the premiere, Beethoven augmented them further by assigning two players to each wind part.Woodwind

Woodwind instruments are a family of musical instruments within the greater category of wind instruments.

Common examples include flute, clarinet, oboe, bassoon, and saxophone. There are two main types of woodwind instruments: flutes and Ree ...

s

:

:2 Flutes

The flute is a member of a family of musical instruments in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, producing sound with a vibrating column of air. Flutes produce sound when the player's air flows across an opening. In th ...

:2 Oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double-reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites.

The most common type of oboe, the soprano oboe pitched in C, ...

s

:2 Clarinet

The clarinet is a Single-reed instrument, single-reed musical instrument in the woodwind family, with a nearly cylindrical bore (wind instruments), bore and a flared bell.

Clarinets comprise a Family (musical instruments), family of instrume ...

s in A, B and C

:2 Bassoon

The bassoon is a musical instrument in the woodwind family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuosity ...

s

:

Brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

:4 Horns in D, B and E

:2 Trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz musical ensemble, ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest Register (music), register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitche ...

s in D and B

:

Percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a percussion mallet, beater including attached or enclosed beaters or Rattle (percussion beater), rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or ...

:Timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion instrument, percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a Membranophone, membrane called a drumhead, ...

:Bass drum

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter usually greater than its depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. The head ...

(fourth movement only)

:Triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called ''vertices'', are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called ''edges'', are one-dimension ...

(fourth movement only)

:Cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs sou ...

s (fourth movement only)

:Soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hertz, Hz to A5 in Choir, choral ...

solo

:Alto

The musical term alto, meaning "high" in Italian (Latin: '' altus''), historically refers to the contrapuntal part higher than the tenor and its associated vocal range. In four-part voice leading alto is the second-highest part, sung in ch ...

solo

:Tenor

A tenor is a type of male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. Composers typically write music for this voice in the range from the second B below m ...

solo

:

:

Strings

:Violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

s I, II

:Viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

s

:Cello

The violoncello ( , ), commonly abbreviated as cello ( ), is a middle pitched bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), tuned i ...

s

:Double bass

The double bass (), also known as the upright bass, the acoustic bass, the bull fiddle, or simply the bass, is the largest and lowest-pitched string instrument, chordophone in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding rare additions ...

es

Form

The symphony is in fourmovements

Movement may refer to:

Generic uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Movement (sign language), a hand movement when signing

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

* Movement (music), a division of a larger c ...

. The structure of each movement is as follows:

:

Beethoven changes the usual pattern of Classical symphonies in placing the scherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often r ...

movement before the slow movement (in symphonies, slow movements are usually placed before scherzi). This was the first time he did this in a symphony, although he had done so in some previous works, including the String Quartet Op. 18 no. 5, the "Archduke" piano trio Op. 97, the ''Hammerklavier'' piano sonata Op. 106. And Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

, too, had used this arrangement in a number of his own works such as the String Quartet No. 30 in E major, as did Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

in three of the Haydn Quartets and the G minor String Quintet.

I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso

The first movement is insonata form

The sonata form (also sonata-allegro form or first movement form) is a musical form, musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of t ...

without an exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

*Exposition (narrative), background information in a story

* Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut alb ...

repeat. It begins with open fifths (A and E) played ''pianissimo

In music, the dynamics of a piece are the variation in loudness between note (music), notes or phrase (music), phrases. Dynamics are indicated by specific musical notation, often in some detail. However, dynamics markings require interpretation ...

'' by tremolo

In music, ''tremolo'' (), or ''tremolando'' (), is a trembling effect. There are multiple types of tremolo: a rapid repetition of a note, an alternation between two different notes, or a variation in volume.

Tremolos may be either ''measured'' ...

strings. The opening, with its perfect fifth quietly emerging, resembles the sound of an orchestra tuning up, steadily building up until the first main theme in D minor

D minor is a minor scale based on D, consisting of the pitches D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. Its key signature has one flat. Its relative major is F major and its parallel major is D major.

The D natural minor scale is:

Changes needed ...

at bar 17.

Before the development enters, the tremolous introduction returns. The development can be divided into four subdivisions, with adheres strictly to the order of themes. The first and second subdivisions are the development of bars 1–2 of the first theme (bars 17–18 of the first movement) . The third subdivision develops bars 3–4 of the first theme (bars 19–20 of the first movement). The fourth subdivision that follows develops bars 1–4 of the second theme (bars 80–83 of the first movement) for three times: first in A minor, then to F major twice.

At the outset of the recapitulation (which repeats the main melodic themes) in bar 301, the theme returns, this time played ''fortissimo'' and in D , rather than D . The movement ends with a massive coda that takes up nearly a quarter of the movement, as in Beethoven's Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', i.e., the third in a series of fractional parts in a sexagesimal number system

Places

* 3rd Street (di ...

and Fifth Symphonies.

A performance of the first movement typically lasts about 15 minutes.

II. Molto vivace

The second movement is a scherzo and trio. Like the first movement, the scherzo is in D minor, with the introduction bearing a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the first movement, a pattern also found in the ''Hammerklavier'' piano sonata, written a few years earlier. At times during the piece, Beethoven specifies one downbeat every three bars—perhaps because of the fast tempo—with the direction ''ritmo di tre battute'' (rhythm of three beats) and one beat every four bars with the direction ''ritmo di quattro battute'' (rhythm of four beats). Normally, a scherzo is intriple time

Triple metre (or Am. triple meter, also known as triple time) is a musical metre characterized by a ''primary'' division of 3 beats to the bar, usually indicated by 3 (simple) or 9 ( compound) in the upper figure of the time signature, with , a ...

. Beethoven wrote this piece in triple time but punctuated it in a way that, when coupled with the tempo, makes it sound as if it is in quadruple time

Duple metre (or Am. duple meter, also known as duple time) is a musical metre characterized by a ''primary'' division of 2 beats to the bar, usually indicated by 2 and multiples (simple) or 6 and multiples ( compound) in the upper figure of the ti ...

.

While adhering to the standard compound ternary design (three-part structure) of a dance movement (scherzo-trio-scherzo or minuet-trio-minuet), the scherzo section has an elaborate internal structure; it is a complete sonata form. Within this sonata form, the first group of the exposition (the statement of the main melodic themes) starts out with a fugue

In classical music, a fugue (, from Latin ''fuga'', meaning "flight" or "escape""Fugue, ''n''." ''The Concise Oxford English Dictionary'', eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford Universit ...

in D minor on the subject below.

For the second subject, it modulates to the unusual key of C major

C major is a major scale based on C, consisting of the pitches C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. C major is one of the most common keys used in music. Its key signature has no flats or sharps. Its relative minor is A minor and its parallel min ...

. The exposition then repeats before a short development section, where Beethoven explores other ideas. The recapitulation (repeating of the melodic themes heard in the opening of the movement) further develops the exposition's themes, also containing timpani solos. A new development section leads to the repeat of the recapitulation, and the scherzo concludes with a brief codetta.

The contrasting trio section is in D major

D major is a major scale based on D (musical note), D, consisting of the pitches D, E (musical note), E, F♯ (musical note), F, G (musical note), G, A (musical note), A, B (musical note), B, and C♯ (musical note), C. Its key signature has two S ...

and in duple time. The trio is the first time the trombones play. Following the trio, the second occurrence of the scherzo, unlike the first, plays through without any repetition, after which there is a brief reprise of the trio, and the movement ends with an abrupt coda.

The duration of the complete second movement is about 14 minutes when two frequently omitted repeats are played.

III. Adagio molto e cantabile

The third movement is a lyrical, slow movement inB major

B major is a major scale based on B. The pitches B, C, D, E, F, G, and A are all part of the B major scale. Its key signature has five sharps. Its relative minor is G-sharp minor, its parallel minor is B minor, and its enharmonic equi ...

—the subdominant

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree () of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance ''below'' the tonic as the dominant is ''above'' the tonicin other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdomina ...

of D minor's relative major key, F major

F major is a major scale based on F, with the pitches F, G, A, B, C, D, and E. Its key signature has one flat.Music Theory'. (1950). United States: Standards and Curriculum Division, Training, Bureau of Naval Personnel. 28. Its relati ...

. It is in a double variation form, with each pair of variations progressively elaborating the rhythm and melodic ideas. The first variation, like the theme, is in time, the second in . The variations are separated by passages in , the first in D major, the second in G major

G major is a major scale based on G (musical note), G, with the pitches G, A (musical note), A, B (musical note), B, C (musical note), C, D (musical note), D, E (musical note), E, and F♯ (musical note), F. Its key signature has one sharp (music ...

, the third in E major

E major is a major scale based on E, consisting of the pitches E, F, G, A, B, C, and D. Its key signature has four sharps. Its relative minor is C-sharp minor and its parallel minor is E minor. Its enharmonic equivalent, F-flat maj ...

, and the fourth in B major

B major is a major scale based on B. The pitches B, C, D, E, F, G, and A are all part of the B major scale. Its key signature has five sharps. Its relative minor is G-sharp minor, its parallel minor is B minor, and its enharmonic equi ...

. The final variation is twice interrupted by episodes in which loud fanfare

A fanfare (or fanfarade or flourish) is a short musical flourish which is typically played by trumpets (including fanfare trumpets), French horns or other brass instruments, often accompanied by percussion. It is a "brief improvised introdu ...

s from the full orchestra are answered by octaves by the first violins. A prominent French horn solo is assigned to the fourth player.

A typical performance of the third movement lasts around 15 minutes.

IV. Finale

The choral finale is Beethoven's musical representation of universal brotherhood based on the "Ode to Joy

"Ode to Joy" ( ) is an ode written in the summer of 1785 by the German poet, playwright, and historian Friedrich Schiller. It was published the following year in the Thalia (German magazine), German magazine ''Thalia''. In 1808, a slightly revi ...

" theme and is in theme and variations form.

The movement starts with an introduction in which musical material from each of the preceding three movements—though none are literal quotations of previous music—are successively presented and then dismissed by instrumental recitatives played by the low strings. Following this, the "Ode to Joy" theme is finally introduced by the cellos and double basses. After three instrumental variations on this theme, the human voice is presented for the first time in the symphony by the baritone soloist, who sings words written by Beethoven himself: Classical era

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

. Its form has been disputed by musicologists, as Nicholas Cook explains:

Cook gives the following table describing the form of the movement:

In line with Cook's remarks, Charles Rosen characterizes the final movement as a symphony within a symphony, played without interruption. Rosen, Charles. '' The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven''. p. 440. New York: Norton, 1997. This "inner symphony" follows the same overall pattern as the Ninth Symphony as a whole, with four "movements":

# Theme and variations with slow introduction. The main theme, first in the cellos and basses, is later recapitulated by voices.

# Scherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often r ...

in a military style. It begins at ''Alla marcia'' (bars 331–594) and concludes with a variation of the main theme with chorus

Chorus may refer to:

Music

* Chorus (song), the part of a song that is repeated several times, usually after each verse

* Chorus effect, the perception of similar sounds from multiple sources as a single, richer sound

* Chorus form, song in whic ...

.

# Slow section with a new theme on the text "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" It begins at ''Andante maestoso'' (bars 595–654).

# Fugato

In classical music, a fugue (, from Latin ''fuga'', meaning "flight" or "escape""Fugue, ''n''." ''The Concise Oxford English Dictionary'', eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford Universit ...

finale on the themes of the first and third "movements". It begins at ''Allegro energico'' (bars 655–762), and two canons on main theme and "Seid unschlungen, Millionen!" respectively. It begins at ''Allegro ma non tanto'' (bars 763–940).

Rosen notes that the movement can also be analysed as a set of variations and simultaneously as a concerto sonata form with double exposition (with the fugato acting both as a development section and the second tutti of the concerto).

Text of the fourth movement

The text is largely taken from

The text is largely taken from Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

's "Ode to Joy

"Ode to Joy" ( ) is an ode written in the summer of 1785 by the German poet, playwright, and historian Friedrich Schiller. It was published the following year in the Thalia (German magazine), German magazine ''Thalia''. In 1808, a slightly revi ...

", with a few additional introductory words written specifically by Beethoven (shown in italics). The text, without repeats, is shown below, with a translation into English. The score includes many repeats.

In the last two sections of the text, Beethoven goes back to the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

sacred music

Religious music (also sacred music) is a type of music that is performed or composed for religious use or through religious influence. It may overlap with ritual music, which is music, sacred or not, performed or composed for or as a ritual. Reli ...

tradition: the composer recalls a liturgical hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

, more specifically a psalmody, using the eighth mode of Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainsong, plainchant, a form of monophony, monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek language, Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed main ...

, the '' Hypomixolydian''. The religious questions, simultaneously with the affirmations and exhortations, are musically characterized by archaistic moments, veritable "Gregorian fossils" inserted into a "quasi-liturgical" structure based on the sequence first versicle – response – second versicle – response – hymn. Beethoven's employment of this sacred music style has the effect of attenuating the interrogative nature of the text when is mentioned the prostration to the supreme being.

Towards the end of the movement, the choir sings the last four lines of the main theme, concluding with "Alle Menschen" before the soloists sing for one last time the song of joy at a slower tempo. The chorus repeats parts of "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!", then quietly sings, "Tochter aus Elysium", and finally, "Freude, schöner Götterfunken, Götterfunken!".

Reception

The symphony was dedicated to theKing of Prussia

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman C ...

, Frederick William III.

Music critics almost universally consider the Ninth Symphony one of Beethoven's greatest works, and among the greatest musical works ever written. The finale, however, has had its detractors: "Early critics rejected he finaleas cryptic and eccentric, the product of a deaf and ageing composer." Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( ; ; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma, to a family of moderate means, recei ...

admired the first three movements but lamented what he saw as the bad writing for the voices in the last movement:

Performance challenges

Metronome markings

Conductors in thehistorically informed performance

Historically informed performance (also referred to as period performance, authentic performance, or HIP) is an approach to the performance of Western classical music, classical music which aims to be faithful to the approach, manner and style of ...

movement, notably Roger Norrington, have used Beethoven's suggested tempos, to mixed reviews. Benjamin Zander has made a case for following Beethoven's metronome

A metronome () is a device that produces an audible click or other sound at a uniform interval that can be set by the user, typically in beats per minute (BPM). Metronomes may also include synchronized visual motion, such as a swinging pendulum ...

markings, both in writing and in performances with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

The Boston Philharmonic Orchestra is a semi-professional orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. It was founded in 1979.

Their concerts take place at Boston's Symphony Hall, New England Conservatory's Jordan Hall and at H ...

and Philharmonia Orchestra of London. Beethoven's metronome still exists and was tested and found accurate, but the original heavy weight (whose position is vital to its accuracy) is missing and many musicians have considered his metronome marks to be unacceptably high.

Re-orchestrations and alterations

A number of conductors have made alterations in the instrumentation of the symphony. Notably,Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

doubled many woodwind passages, a modification greatly extended by Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic music, Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and ...

,Raymond Holden, "The iconic symphony: performing Beethoven's Ninth Wagner's Way" ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' was an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainzer's Musical Times and Singing Circular'', but in 1844 he sold it to Alfr ...

'', Winter 2011 who revised the orchestration of the Ninth to make it sound like what he believed Beethoven would have wanted if given a modern orchestra. Wagner's Dresden performance of 1864 was the first to place the chorus and the solo singers behind the orchestra as has since become standard; previous conductors placed them between the orchestra and the audience.

2nd bassoon doubling basses in the finale

Beethoven's indication that the 2nd bassoon should double the basses in bars 115–164 of the finale was not included in theBreitkopf & Härtel

Breitkopf & Härtel () is a German Music publisher, music publishing house. Founded in 1719 in Leipzig by Bernhard Christoph Breitkopf, it is the world's oldest music publisher.

Overview

The catalogue contains over 1,000 composers, 8,000 works ...

parts, though it was included in the full score.

Notable performances and recordings

The British première of the symphony was presented on 21 March 1825 by its commissioners, the Philharmonic Society of London, at itsArgyll Rooms

The Argyll Rooms (sometimes spelled Argyle) was an entertainment venue on Little Argyll Street, Regent Street, London, England, opened in 1806. It was rebuilt in 1818 due to the design of Regent Street. It burned down in 1830, but was rebuilt, b ...

conducted by Sir George Smart and with the choral part sung in Italian. The American première was presented on 20 May 1846 by the newly formed New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic is an American symphony orchestra based in New York City. Known officially as the ''Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc.'', and globally known as the ''New York Philharmonic Orchestra'' (NYPO) or the ''New Yo ...

at Castle Garden (in an attempt to raise funds for a new concert hall), conducted by the English-born George Loder, with the choral part translated into English for the first time. Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British-born American conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra. H ...

's 1934 Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription concerts, n ...

and 1941 NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra conceived by David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, the parent corporation of the National Broadcasting Company especially for the conductor Arturo Toscanini. The NBC ...

recordings also used English lyrics in the fourth movement.

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

inaugurated his Bayreuth Festspielhaus

The ''Bayreuth Festspielhaus'' or Bayreuth Festival Theatre (, ) is an opera house north of Bayreuth, Germany, built by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner and dedicated solely to the performance of his stage works. It is the venue ...

by conducting the Ninth; since then it is traditional to open each Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival () is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of stage works by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived and promoted the idea of a special ...

with a performance of the Ninth. Following the festival's temporary suspension after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , ; ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is regarded as one of the greatest Symphony, symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a majo ...

and the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra reinaugurated it with a performance of the Ninth.

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; born Louis Bernstein; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was th ...

conducted a version of the Ninth Symphony at the Konzerthaus Berlin

The Konzerthaus Berlin is a concert hall in Berlin, the home of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin. Situated on the Gendarmenmarkt square in the central Mitte district of the city, it was originally built as a theater. It initially operated from 1 ...

with (Freedom) replacing (Joy), to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (, ) on 9 November in German history, 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, marked the beginning of the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain, as East Berlin transit restrictions we ...

during Christmas of 1989. This concert was performed by an orchestra and chorus made up of many nationalities: from East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (, BRSO) is a German radio orchestra. Based in Munich, Germany, it is one of the city's four orchestras. The BRSO is one of two full-size symphony orchestras operated under the auspices of Bayerischer Rundf ...

and Chorus, the Chorus of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (''Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin'') is a German symphony orchestra based in Berlin. In Berlin, the orchestra gives concerts at the Konzerthaus Berlin and at the Berliner Philharmonie. The orchestra has a ...

, and members of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden, the Philharmonischer Kinderchor Dresden (Philharmonic Children's Choir Dresden); from the Soviet Union, members of the orchestra of the Kirov Theatre; from the United Kingdom, members of the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

; from the US, members of the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic is an American symphony orchestra based in New York City. Known officially as the ''Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc.'', and globally known as the ''New York Philharmonic Orchestra'' (NYPO) or the ''New Yo ...

; and from France, members of the Orchestre de Paris

The Orchestre de Paris () is a French orchestra based in Paris. The orchestra currently performs most of its concerts at the Philharmonie de Paris.

History

In 1967, following the dissolution of the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du ...

. Soloists were June Anderson

June Anderson (born December 30, 1952) is an American dramatic coloratura soprano. She is known for ''bel canto'' performances of Rossini, Donizetti, and Vincenzo Bellini.

Subsequently, she has extended her repertoire to include a wide variety o ...

, soprano, Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano, Klaus König, tenor, and Jan-Hendrik Rootering, bass. Bernstein conducted the Ninth Symphony one last time with soloists Lucia Popp, soprano, Ute Trekel-Burckhardt, contralto, Wiesław Ochman

Wiesław Ochman (; born 6 February 1937) is a Polish tenor.

Life and career

In 1960, he graduated from the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków, Poland. Ochman began learning voice under the direction of Gustaw Serafin in Kraków ...

, tenor, and , bass, at the Prague Spring Festival

The Prague Spring International Music Festival (, commonly , Prague Spring) is a classical music festival held every year in Prague, Czech Republic, with symphony orchestras and chamber music ensembles from around the world.

The first festival ...

with the Czech Philharmonic and in June 1990; he died four months later in October of the same year.

In 1998, Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa

was a Japanese conductor known internationally for his work as music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the San Francisco Symphony, and especially the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), where he served from 1973 for 29 years. After cond ...

conducted the fourth movement for the 1998 Winter Olympics opening ceremony

The opening ceremony of the 1998 Winter Olympics took place at Nagano Olympic Stadium, Nagano, Japan, on 7 February 1998. It began at 11:00 JST and finished at approximately 14:00 JST. As mandated by the Olympic Charter, the proceedings comb ...

, with six different choirs simultaneously singing from Japan, Germany, South Africa, China, the United States, and Australia.

In 1923, the first complete recording of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was made by the acoustic recording

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English) or a vinyl record (for later varieties only) is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The g ...

process and conducted by Bruno Seidler-Winkler. The recording was issued by Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon (; DGG) is a German classical music record label that was the precursor of the corporation PolyGram. Headquartered in Berlin Friedrichshain, it is now part of Universal Music Group (UMG) since its merger with the UMG family of ...

in Germany; the records were issued in the United States on the Vocalion label. The first electrical recording of the Ninth was recorded in England in 1926, with Felix Weingartner

Paul Felix Weingartner, Edler von Münzberg (2 June 1863 – 7 May 1942) was an Austrian Conducting, conductor, composer and pianist.

Life and career

Weingartner was born in Zadar, Zara, Kingdom of Dalmatia, Dalmatia, Austrian Empire (now ...

conducting the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

, issued by Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American reco ...

. The first complete American recording was made by RCA Victor

RCA Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Group Corporation. It is one of Sony Music's four flagship labels, alongside Columbia Records (its former longtime rival), Arista Records and Epic ...

in 1934 with Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British-born American conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra. H ...

conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription concerts, n ...

. Since the late 20th century, the Ninth has been recorded regularly by period performers, including Roger Norrington, Christopher Hogwood

Christopher Jarvis Haley Hogwood (10 September 194124 September 2014) was an English Conducting, conductor, harpsichordist, and Musicology, musicologist. Founder of the early music ensemble the Academy of Ancient Music, he was an authority on h ...

, and Sir John Eliot Gardiner

Sir John Eliot Gardiner (born 20 April 1943) is an English conductor, particularly known for his performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, especially the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage of 2000, performing Church cantata (Bach), Bach's church ...

.

The BBC Proms Youth Choir performed the piece alongside Georg Solti

Sir Georg Solti ( , ; born György Stern; 21 October 1912 – 5 September 1997) was a Hungarian-British orchestral and operatic conductor, known for his appearances with opera companies in Munich, Frankfurt, and London, and as a long-servi ...

's UNESCO World Orchestra for Peace at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

during the 2018 Proms at Prom 9, titled "War & Peace" as a commemoration to the centenary of the end of World War One

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting took place mainly in Europe and th ...

.

At 79 minutes, one of the longest Ninths recorded is Karl Böhm

Karl August Leopold Böhm (28 August 1894 – 14 August 1981) was an Austrian conductor. He was best known for his performances of the music of Mozart, Wagner, and Richard Strauss.

Life and career

Education

Karl Böhm was born in Graz, St ...

's, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic

Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; ) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. Its members are selected from the orchestra of ...

in 1981 with Jessye Norman

Jessye Mae Norman (September 15, 1945 – September 30, 2019) was an American opera singer and recitalist. She was able to perform dramatic soprano roles, but did not limit herself to that voice type. A commanding presence on operatic, concert ...

and Plácido Domingo

José Plácido Domingo Embil (born 21 January 1941) is a Spanish opera singer, conductor, and arts administrator. He has recorded over a hundred complete operas and is well known for his versatility, regularly performing in Italian, French, ...

among the soloists.

Influence

Many later composers of the

Many later composers of the Romantic period

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

and beyond were influenced by the Ninth Symphony.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; ; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period (music), Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, oft ...

' Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the "Ode to Joy" theme from the last movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted "Any fool can see that!" Brahms's first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as "Beethoven's Tenth".

The Ninth Symphony influenced the forms that Anton Bruckner

Joseph Anton Bruckner (; ; 4 September 182411 October 1896) was an Austrian composer and organist best known for his Symphonies by Anton Bruckner, symphonies and sacred music, which includes List of masses by Anton Bruckner, Masses, Te Deum (Br ...

used for the movements of his symphonies. His Symphony No. 3 is in the same key (D minor) as Beethoven's 9th and makes substantial use of thematic ideas from it. The slow movement of Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 uses the A–B–A–B–A form found in the 3rd movement of Beethoven's piece and takes various figurations from it.

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (''From the New World''), Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák ( ; ; 8September 18411May 1904) was a Czech composer. He frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia, following the Romantic-era nationalist example of his predec ...

pays homage to the scherzo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.

Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók (; ; 25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as Hunga ...

borrowed the opening motif of the scherzo from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to introduce the second movement (scherzo) in his own Four Orchestral Pieces, Op. 12 (Sz 51).

Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten as o ...

in his Third Symphony (1972) quotes the opening of the finale of Beethoven's Ninth and then criticises the utopian understanding of the brotherhood of man as expressed in the Ode to Joy

"Ode to Joy" ( ) is an ode written in the summer of 1785 by the German poet, playwright, and historian Friedrich Schiller. It was published the following year in the Thalia (German magazine), German magazine ''Thalia''. In 1808, a slightly revi ...

and instead stresses man's capacity for both good and evil.

In the film ''The Pervert's Guide to Ideology

''The Pervert's Guide to Ideology'' is a 2012 British documentary film directed by Sophie Fiennes and written and presented by Slovenian philosopher and psychoanalytic theorist Slavoj Žižek. It is a sequel to Fiennes's 2006 documentary '' The ...

'', the philosopher Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek ( ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian Marxist philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.

He is the international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, Global Distin ...

comments on the use of the Ode by Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

, the Chinese Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

, the East-West German Olympic team, Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

, Abimael Guzmán

Manuel Rubén Abimael Guzmán Reinoso (; 3 December 1934 − 11 September 2021), also known by his ''nom de guerre'' Chairman Gonzalo (), was a Peruvian Maoist guerrilla leader. He founded the organization Communist Party of Peru – Shining ...

(leader of the Shining Path), and the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

and the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

.

Compact disc format

One legend is that thecompact disc

The compact disc (CD) is a Digital media, digital optical disc data storage format co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. It employs the Compact Disc Digital Audio (CD-DA) standard and was capable of hol ...

was deliberately designed to have a 74-minute playing time so that it could accommodate Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Kees Immink, Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), simply branded Philips, is a Dutch multinational health technology company that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, its world headquarters have been situated in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarter ...

' chief engineer, who developed the CD, recalls that a commercial tug-of-war between the development partners, Sony

is a Japanese multinational conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at Sony City in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. The Sony Group encompasses various businesses, including Sony Corporation (electronics), Sony Semiconductor Solutions (i ...

and Philips, led to a settlement in a neutral 12-cm diameter format. The 1951 performance of the Ninth Symphony conducted by Furtwängler was brought forward as the perfect excuse for the change, and was put forth in a Philips news release celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Compact Disc as the reason for the 74-minute length.

TV theme music

'' The Huntley–Brinkley Report'' used the opening to the second movement as its theme music during the run of the program onNBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

from 1956 until 1970. The theme was taken from the 1952 RCA Victor

RCA Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Group Corporation. It is one of Sony Music's four flagship labels, alongside Columbia Records (its former longtime rival), Arista Records and Epic ...

recording of the Ninth Symphony by the NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra conceived by David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, the parent corporation of the National Broadcasting Company especially for the conductor Arturo Toscanini. The NBC ...

conducted by Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orche ...

. A synthesized version of the opening bars of the second movement were also used as the theme for ''Countdown with Keith Olbermann

''Countdown with Keith Olbermann'' is a weekday podcast that originated as an hour-long weeknight news and political commentary program hosted by Keith Olbermann that aired on MSNBC from 2003 to 2011 and on Current TV from 2011 to 2012. The show ...

'' on MSNBC

MSNBC is an American cable news channel owned by the NBCUniversal News Group division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. Launched on July 15, 1996, and headquartered at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan, the channel primarily broadcasts r ...

and Current TV

Current TV was an American television channel which broadcast from August 1, 2005, to August 20, 2013. Prior INdTV founders Al Gore and Joel Hyatt, with Ronald Burkle, each held a sizable stake in Current TV. Comcast and DirecTV each held a small ...

. A rock guitar version of the "Ode to Joy" theme was used as the theme for '' Suddenly Susan'' in its first season.

Use as (national) anthem

During the division of Germany in theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, the "Ode to Joy" segment of the symphony was played in lieu of a national anthem at the Olympic Games for the United Team of Germany

The United Team of Germany () was a combined team of athletes from West Germany and East Germany that competed in the 1956, 1960 and 1964 Winter Olympic Games, Winter and Summer Olympic Games. In 1956, the team also included athletes from a third ...

between 1956 and 1968. In 1972, the musical backing (without the words) was adopted as the Anthem of Europe

The Anthem of Europe or European Anthem, also known as Ode to Joy, is a piece of instrumental music adapted from the prelude of the final movement of Beethoven's 9th Symphony composed in 1823, originally set to words adapted from Friedric ...

by the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

and subsequently by the European Communities

The European Communities (EC) were three international organizations that were governed by the same set of Institutions of the European Union, institutions. These were the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Atomic Energy Co ...

(now the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

) in 1985. The "Ode to Joy" was used as the national anthem of Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

between 1974 and 1979, as " Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia". During the early 1990s, South Africa used an instrumental version of "Ode to Joy" in lieu of its national anthem at the time " Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" at sporting events, though it was never actually adopted as an official national anthem.

Use as a hymn melody

In 1907, thePresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

pastor Henry van Dyke Jr. wrote the hymn " Joyful, Joyful, we adore thee" while staying at Williams College

Williams College is a Private college, private liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established as a men's college in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim ...

. The hymn is commonly sung in English-language churches to the "Ode to Joy" melody from this symphony.

Year-end tradition

The German workers' movement began the tradition of performing the Ninth Symphony on New Year's Eve in 1918. Performances started at 11 p.m. so that the symphony's finale would be played at the beginning of the new year. This tradition continued during the Nazi period and was also observed byEast Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

after the war.

The Ninth Symphony is traditionally performed throughout Japan at the end of the year. In December 2009, for example, there were 55 performances of the symphony by various major orchestras and choirs in Japan.Brasor, Philip,Japan makes Beethoven's Ninth No. 1 for the holidays

, ''

The Japan Times

''The Japan Times'' is Japan's largest and oldest English-language daily newspaper. It is published by , a subsidiary of News2u Holdings, Inc. It is headquartered in the in Kioicho, Chiyoda, Tokyo.

History

''The Japan Times'' was launched by ...

'', 24 December 2010, p. 20, retrieved on 24 December 2010; Uranaka, Taiga,

Beethoven concert to fete students' wartime sendoff

, ''The Japan Times'', 1 December 1999, retrieved on 24 December 2010. It was introduced to Japan during World War I by German prisoners held at the Bandō prisoner-of-war camp. Japanese orchestras, notably the

NHK Symphony Orchestra

The is a Japanese broadcast orchestra based in Tokyo. The orchestra gives concerts in several venues, including the NHK Hall, Suntory Hall, and the Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall.

History

The orchestra was founded as the ''New Symphony Orchestr ...

, began performing the symphony in 1925 and during World War II; the Imperial government

The name imperial government () denotes two organs, created in 1500 and 1521, in the Holy Roman Empire, Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation to enable a unified political leadership, with input from the Princes. Both were composed of the empero ...

promoted performances of the symphony, including on New Year's Eve. In an effort to capitalize on its popularity, orchestras and choruses undergoing economic hard times during Japan's reconstruction performed the piece at year's end. In the 1960s, these year-end performances of the symphony became more widespread, and included the participation of local choirs and orchestras, firmly establishing a tradition that continues today. Some of these performances feature massed choirs of up to 10,000 singers.

WQXR-FM

WQXR-FM (105.9 FM) is an American non-commercial classical radio station, licensed to Newark, New Jersey, and serving the North Jersey and New York City area. It is owned by the nonprofit organization New York Public Radio (NYPR), which also op ...

, a classical radio station

Radio broadcasting is the broadcasting of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based rad ...

serving the New York metropolitan area

The New York metropolitan area, also called the Tri-State area and sometimes referred to as Greater New York, is the List of cities by GDP, largest metropolitan economy in the world, with a List of U.S. metropolitan areas by GDP, gross metropo ...

, ends every year with a countdown of the pieces of classical music most requested in a survey held every December; though any piece could win the place of honor and thus welcome the New Year, i.e. play through midnight on January 1, Beethoven's Choral has won in every year on record.

Other choral symphonies

Prior to Beethoven's ninth, symphonies had not used choral forces and the piece thus established the genre ofchoral symphony

A choral symphony is a musical composition for orchestra, choir, and sometimes solo (music), solo vocalists that, in its internal workings and overall musical architecture, adheres broadly to symphony, symphonic musical form. The term "choral s ...

. Numbered choral symphonies as part of a cycle of otherwise instrumental works have subsequently been written by numerous composers, including Felix Mendelssohn