Babington Plot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen

Reacting to the growing threat posed by Catholics, urged on by the pope and other Catholic monarchs in Europe,

Reacting to the growing threat posed by Catholics, urged on by the pope and other Catholic monarchs in Europe,

After the

After the

online

(April 1907) pp. 356–365 *Read, Conyers. ''Mr Secretary Walsingham and the policy of Queen Elizabeth'' 3 vols. (1925) *Shepherd, J.E.C. ''The Babington Plot: Jesuit Intrigue in Elizabethan England''. Toronto, Ont.: Wittenburg Publications, 1987. 171 pp. *Williams, Penry. "Babington, Anthony (1561–1586)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004

accessed 18 Sept 2011

*''Military Heritage'' August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 20–23, . *Briscoe, Alexsandra, "Elizabeth's Spy Network", ''BBC History'

online

(17 February 2011)

Portraits of Babington Plotters at their Execution and Ballad Describing their Ordeal

{{authority control 1586 in England 1586 in Scotland Espionage scandals and incidents Babington Plot History of cryptography History of Catholicism in England History of Catholicism in Scotland Elizabeth I Mary, Queen of Scots Attempted coups d'état in Europe 1586 in Christianity 16th-century anti-Protestantism 16th-century coups d'état

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, a Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, and put Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, her Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter sent by Mary (who had been imprisoned for 19 years since 1568 in England at the behest of Elizabeth) in which she consented to the assassination of Elizabeth.

The long-term goal of the plot was the invasion of England by the Spanish forces of King Philip II and the Catholic League in France, leading to the restoration of the old religion. The plot was discovered by Elizabeth's spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

and used to entrap Mary for the purpose of removing her as a claimant to the English throne.

The chief conspirators were Anthony Babington

Anthony Babington (24 October 156120 September 1586) was an English gentleman convicted of plotting the assassination of Elizabeth I of England and conspiring with the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, for which he was hanged, drawn and quartered ...

and John Ballard. Babington, a young recusant

Recusancy (from ) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign of Elizabeth I, and temporarily repea ...

, was recruited by Ballard, a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest who hoped to rescue the Scottish queen. Working for Walsingham were double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

s Robert Poley

Robert Poley, or Pooley (fl. 1568– aft. 1602) was an English double agent, government messenger and ''agent provocateur'' employed by members of the Privy Council during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; he was described as "the very genius of ...

and Gilbert Gifford, as well as Thomas Phelippes, a spy agent and cryptanalyst

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic se ...

, and the Puritan spy Maliverey Catilyn. The turbulent Catholic deacon Gifford had been in Walsingham's service since the end of 1585 or the beginning of 1586. Gifford obtained a letter of introduction to Queen Mary from a confidant and spy for her, Thomas Morgan. Walsingham then placed double agent Gifford and spy decipherer Phelippes inside Chartley Castle, where Queen Mary was imprisoned. Gifford organised the Walsingham plan to place Babington's and Queen Mary's encrypted

In cryptography, encryption (more specifically, encoding) is the process of transforming information in a way that, ideally, only authorized parties can decode. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plain ...

communications into a beer barrel cork which were then intercepted by Phelippes, decoded and sent to Walsingham.

On 7 July 1586, the only Babington letter that was sent to Mary was decoded by Phelippes. Mary responded in code on 17 July 1586 ordering the would-be rescuers to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. The response letter also included deciphered phrases indicating her desire to be rescued: "The affairs being thus prepared" and "I may suddenly be transported out of this place". At the Fotheringay trial in October 1586, Elizabeth's Lord High Treasurer William Cecil Lord Burghleyand Walsingham used the letter against Mary who refused to admit that she was guilty. However, Mary was betrayed by her secretaries Nau and Curle, who confessed under pressure that the letter was mainly truthful.

Mary's imprisonment

Mary, Queen of Scots, a Roman Catholic, was regarded by Roman Catholics as the legitimate heir to the throne of England. In 1568, she escaped imprisonment by Scottish rebels and sought the aid of her first cousin once removed,Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, a year after her forced abdication from the throne of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

. The issuance of the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

'' Regnans in Excelsis'' by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

on 25 February 1570, granted English Catholics authority to overthrow the English queen. Queen Mary became the focal point of numerous plots and intrigues to restore England to its former religion, Catholicism, and to depose Elizabeth and even to take her life. Rather than rendering the expected aid, Elizabeth imprisoned Mary for nineteen years in the charge of a succession of jailers, principally the Earl of Shrewsbury

Earl of Shrewsbury () is a hereditary title of nobility created twice in the Peerage of England. The second earldom dates to 1442. The holder of the Earldom of Shrewsbury also holds the title of Earl of Waterford (1446) in the Peerage of Ireland ...

.

In 1584, Elizabeth's Privy Council signed a "Bond of Association

The Bond of Association was a document created in 1584 by Francis Walsingham and William Cecil after the failure of the Throckmorton Plot in 1583. Its purpose was to deter attempts to assassinate Elizabeth I.

Contents

The document obliged all ...

" designed by Cecil and Walsingham which stated that anyone within the line of succession to the throne ''on whose behalf'' anyone plotted against the Queen, would be excluded from the line and executed. This was agreed upon by hundreds of Englishmen, who likewise signed the Bond. Mary also agreed to sign the Bond. The following year, Parliament passed the Act of Association, which provided for the execution of anyone who would benefit from the death of the Queen if a plot against her was discovered. Because of the bond, Mary could be executed if a plot was initiated by others that could lead to her accession to England's throne.

In 1585, Elizabeth ordered Mary to be transferred in a coach and under heavy guard and placed under the strictest confinement at Chartley Hall in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

, under the control of Sir Amias Paulet. She was prohibited any correspondence with the outside world. Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

Paulet was chosen by Queen Elizabeth in part because he abhorred Queen Mary's Catholic faith.

Reacting to the growing threat posed by Catholics, urged on by the pope and other Catholic monarchs in Europe,

Reacting to the growing threat posed by Catholics, urged on by the pope and other Catholic monarchs in Europe, Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

, Queen Elizabeth's Secretary of State and spymaster, together with William Cecil, Elizabeth's chief advisor, realised that if Mary could be implicated in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth, she could be executed and the papist

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

threat diminished. As he wrote to the Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

: "So long as that devilish woman lives, neither Her Majesty must make account to continue in quiet possession of her crown, nor her faithful servants assure themselves of safety of their lives.", as quoted by

Walsingham used Babington to ensnare Queen Mary by sending his double agent, Gilbert Gifford to Paris to obtain the confidence of Morgan, then locked in the Bastille. Morgan previously worked for George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, an earlier jailer of Queen Mary. Through Shrewsbury, Queen Mary became acquainted with Morgan. Queen Mary sent Morgan to Paris to deliver letters to the French court. While in Paris, Morgan became involved in a previous plot designed by William Parry, which resulted in Morgan's incarceration in the Bastille. In 1585 Gifford was arrested returning to England while coming through Rye in Sussex with letters of introduction from Morgan to Queen Mary. Walsingham released Gifford to work as a double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

, in the Babington Plot. Gifford used the alias "No. 4" just as he had used other aliases such as Colerdin, Pietro and Cornelys. Walsingham had Gifford function as a courier in the entrapment plot against Queen Mary.

Plot

The Babington plot was related to several separate plans: *solicitation of a Spanish invasion of England with the purpose of deposing Protestant Queen Elizabeth and replacing her with Catholic Queen Mary; *a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. *Mary would be freed by the plotters, perhaps while riding in open country near Chartley. At the behest of Mary's French supporters, John Ballard, aJesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest and agent of the Roman Church, went to England on various occasions in 1585 to secure promises of aid from the northern Catholic gentry on behalf of Mary. In March 1586, he met with John Savage, an ex-soldier who was involved in a separate plot against Elizabeth and who had sworn an oath to assassinate the queen. He was resolved in this plot after consulting with three friends: Dr. William Gifford, Christopher Hodgson and Gilbert Gifford. Gilbert Gifford had been arrested by Walsingham and agreed to be a double agent. Gifford was already in Walsingham's employ by the time Savage was going ahead with the plot, according to Conyers Read. Later that same year, Gifford reported to Charles Paget and the Spanish diplomat Don Bernardino de Mendoza, and told them that English Catholics were prepared to mount an insurrection against Elizabeth, provided that they would be assured of foreign support. While it was uncertain whether Ballard's report of the extent of Catholic opposition was accurate, what was certain is that he was able to secure assurances that support would be forthcoming. He then returned to England, where he persuaded a member of the Catholic gentry, Anthony Babington, to lead and organise the English Catholics against Elizabeth. Ballard informed Babington about the plans that had been so far proposed. Babington's later confession made it clear that Ballard was sure of the support of the Catholic League:

Despite this assurance of this foreign support, Babington was hesitant, as he thought that no foreign invasion would succeed for as long as Elizabeth remained, to which Ballard answered that the plans of John Savage would take care of that. After a lengthy discussion with friends and soon-to-be fellow conspirators, Babington consented to join and to lead the conspiracy.

Unfortunately for the conspirators, Walsingham was certainly aware of some of the aspects of the plot, based on reports by his spies, most notably Gilbert Gifford, who kept tabs on all the major participants. While he could have shut down some part of the plot and arrested some of those involved within reach, he still lacked any piece of evidence that would prove Queen Mary's active participation in the plot and he feared to commit any mistake which might cost Elizabeth her life.

Infiltration

After the

After the Throckmorton Plot

The 1583 Throckmorton Plot was one of a series of attempts by English Roman Catholics to depose Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, then held under house arrest in England. The alleged objective was to facilitate a Sp ...

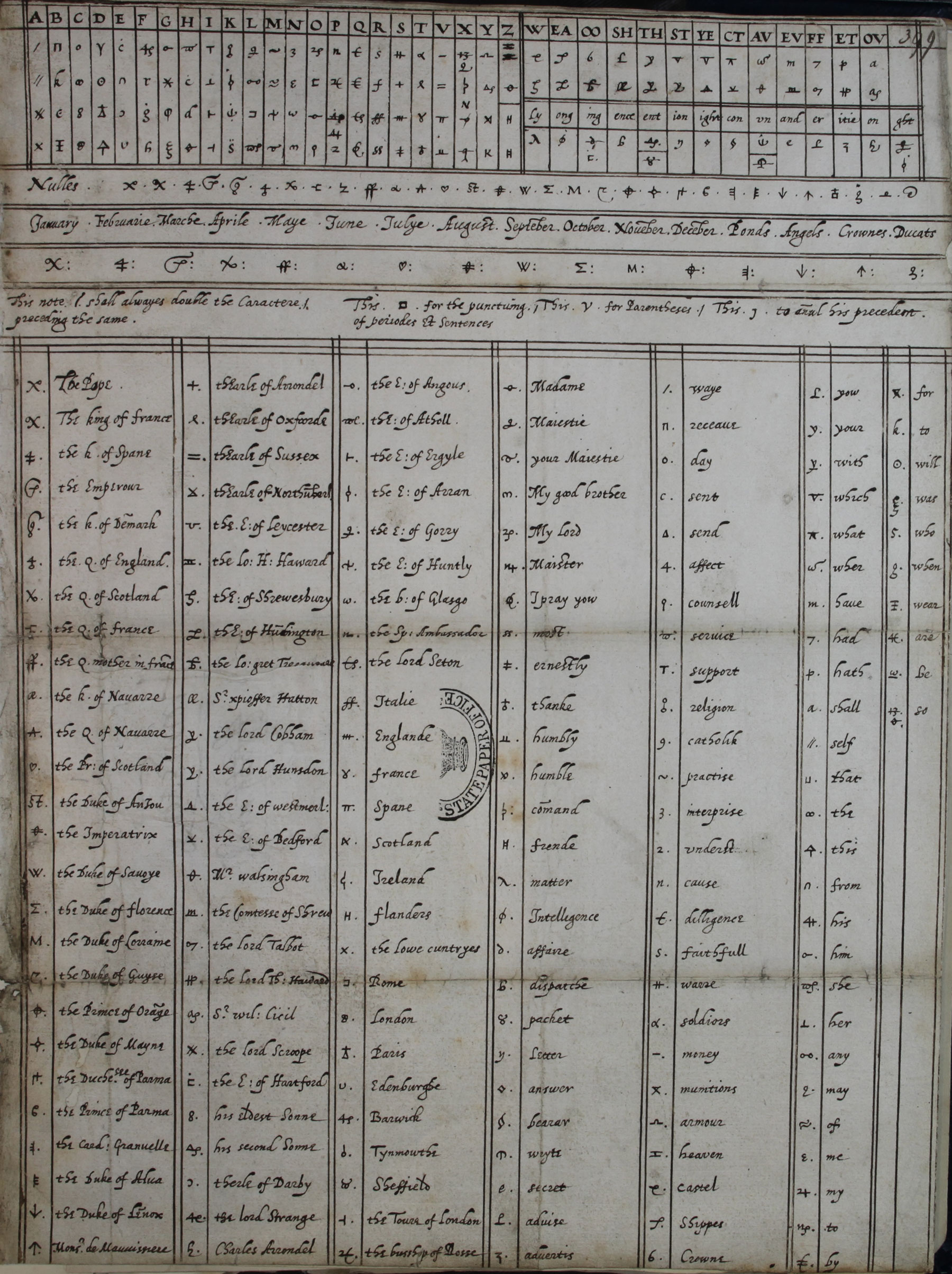

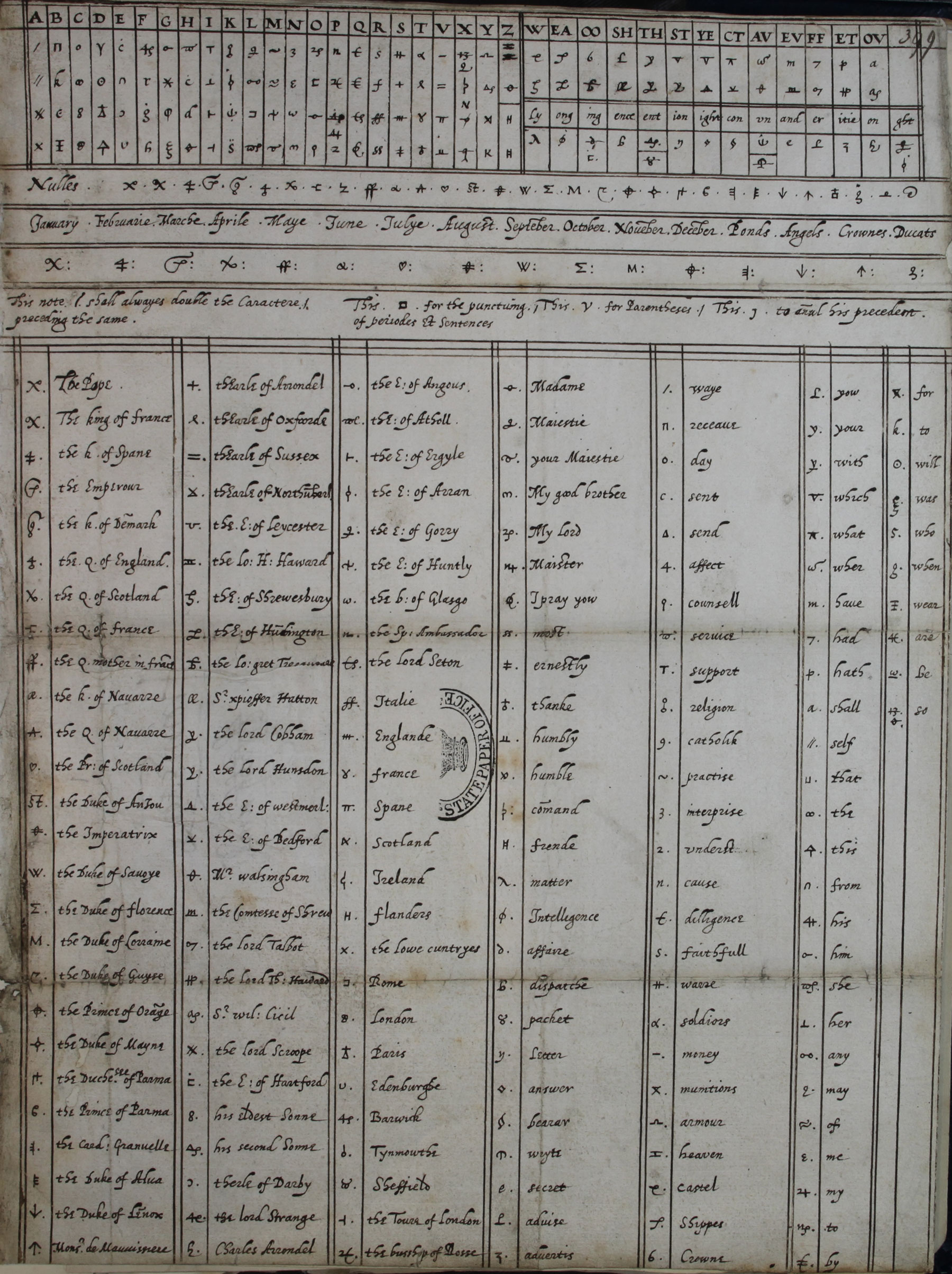

, Queen Elizabeth had issued a decree in July 1584, which prevented all communication to and from Mary. However, Walsingham and Cecil realised that that decree also impaired their ability to entrap Mary. They needed evidence for which she could be executed based on their Bond of Association tenets. Thus Walsingham established a new line of communication, one which he could carefully control without incurring any suspicion from Mary. Gifford approached the French ambassador to England, Guillaume de l'Aubespine, Baron de Châteauneuf-sur-Cher, and described the new correspondence arrangement that had been designed by Walsingham. Gifford and jailer Paulet had arranged for a local brewer to facilitate the movement of messages between Queen Mary and her supporters by placing them in a watertight box inside a beer barrel. Thomas Phelippes, a cipher and language expert in Walsingham's employ, was then quartered at Chartley Hall to receive the messages, decode them and send them to Walsingham. Gifford submitted a code table (supplied by Walsingham) to Chateauneuf and requested the first message be sent to Mary.

All subsequent messages to Mary would be sent via diplomatic packets to Chateauneuf, who then passed them on to Gifford. Gifford would pass them on to Walsingham, who would confide them to Phelippes. The cipher used was a nomenclator cipher. Phelippes would decode and make a copy of the letter. The letter was then resealed and given back to Gifford, who would pass it on to the brewer. The brewer would then smuggle the letter to Mary. If Mary sent a letter to her supporters, it would go through the reverse process. In short order, every message coming to and from Chartley was intercepted and read by Walsingham.

Correspondence

Babington wrote to Mary: This letter was received by Mary on 14 July 1586, who was in a dark mood knowing that her son had betrayed her in favour of Elizabeth, and three days later she replied to Babington in a long letter in which she outlined the components of a successful rescue and the need to assassinate Elizabeth. She also stressed the necessity of foreign aid if the rescue attempt was to succeed: Mary, in her response letter, advised the would-be rescuers to confront thePuritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s and to link her case to the Queen of England as her heir.

Mary was clear in her support for the murder of Elizabeth if that would have led to her liberty and Catholic domination of England. In addition, Queen Mary supported in that letter, and in another one to Ambassador Bernardino de Mendoza, a Spanish invasion of England.

The letter was again intercepted and deciphered by Phelippes. But this time, Phelippes, on the direction of Walsingham, kept the original and made a copy, adding a request for the names of the conspirators:

Then, a letter was sent that would destroy Mary's life.

Arrests, trials and executions

John Ballard was arrested on 4 August 1586, and under torture he confessed and implicated Babington. Although Babington was able to receive the letter with the postscript, he was not able to reply with the names of the conspirators, as he was arrested. Others were taken prisoner by 15 August 1586. Mary's two secretaries, Claude Nau and Gilbert Curle, and a clerk Jérôme Pasquier were likewise taken into custody and interrogated. A large chest filled with Mary's papers seized at Chartley was taken to London. The conspirators were sentenced to death fortreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

and conspiracy against the crown, and were to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. This first group included Babington, Ballard, Chidiock Tichborne, Thomas Salisbury, Henry Donn, Robert Barnewell and John Savage. A further group of seven men including Edward Habington, Charles Tilney, Edward Jones, John Charnock, John Travers, Jerome Bellamy, and Robert Gage, were tried and convicted shortly afterward. Ballard and Babington were executed on 20 September 1586 along with the other men who had been tried with them. Such was the public outcry at the horror of their execution that Elizabeth changed the order for the second group to be allowed to hang until "quite dead" before disembowelling and quartering.

In October 1586, Mary was sent to be tried at Fotheringhay Castle

Fotheringhay Castle, also known as Fotheringay Castle, was a High Middle Age Norman Motte-and-bailey castle in the village of Fotheringhay to the north of the market town of Oundle, Northamptonshire, England (). It was probably founded ar ...

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

by 46 English lords, bishops and earls. She was not permitted legal counsel, not permitted to review the evidence against her, nor to call witnesses. Portions of Phellipes' letter translations were read at the trial. Mary denied knowing Babington and Ballard, but it was insisted that she had sent a reply to Babington using the same cipher code, entrusting the letter to a servant in a blue coat. Mary was convicted of treason against England. One English Lord voted not guilty. Elizabeth signed her cousin-once-removed's death warrant, and on 8 February 1587, in front of 300 witnesses, Mary, Queen of Scots, was executed by beheading.

In literature

'' Mary Stuart'' (), a dramatised version of the last days ofMary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, including the Babington Plot, was written by Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

and performed in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

, Germany, in 1800. This in turn formed the basis for '' Maria Stuarda'', an opera by Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian Romantic composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the ''bel canto'' opera ...

, in 1835. Although the Babington Plot occurs before the events of the opera, and is only referenced twice during the opera, the second such occasion being Mary admitting her own part in it in private to her confessor (a role taken by Lord Talbot in the opera, although not in real life).

The story of the Babington Plot is dramatised in the novel ''Conies in the Hay'' by Jane Lane (), and features prominently in Anthony Burgess

John Anthony Burgess Wilson, (; 25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993) who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was an English writer and composer.

Although Burgess was primarily a comic writer, his Utopian and dystopian fiction, dy ...

's '' A Dead Man in Deptford''. A fictional account is given in the ''My Story'' book series, ''The Queen's Spies'' (retitled ''To Kill A Queen'' 2008) told in diary format by a fictional Elizabethan girl, Kitty.

The Babington plot forms the historical backgroundand provides much of the intriguefor ''Holy Spy'', the 7th in the historical detective series by Rory Clements, featuring John Shakespeare, an intelligencer for Walsingham

Walsingham () is a civil parish in North Norfolk, England, famous for its religious shrines in honour of Mary, mother of Jesus. It also contains the ruins of two medieval Christian monasticism, monastic houses.Ordnance Survey (2002). ''OS Expl ...

and elder brother of the more famous Will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

.

The simplified version of the Babington plot is also the subject of the children's or Young Adult novel ''A Traveller in Time'' (1939), by Alison Uttley

Alison Jane Uttley ( Taylor; 17 December 1884 – 7 May 1976) was an English writer of over 100 books. She is best known for a children's series about Little Grey Rabbit and Sam Pig. She is also remembered for a pioneering time slip novel for ch ...

, who grew up near the Babington family home in Derbyshire. A young modern girl finds that she slips back to the time shortly before the Plot is about to be implemented. This was later made into a BBC TV mini-series in 1978, with small changes to the original novel.

The Babington Plot is also dramatized in the 2017 Ken Follett novel '' A Column of Fire'', in Jacopo della Quercia's 2015 novel ''License to Quill'', and in SJ Parris's 2020 novel ''Execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

'', the latest of her novels featuring Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

as protagonist.

The Babington Plot is also dramatized in the 2024 T.S. Milbourne novel "Gilbert Gifford".

The novel focuses on Gilbert Gifford, the double agent in the Babington Plot, and portrays his complicated position through the dramatization of the people involved in the plot.

The plot figures prominently in the first chapter of '' The Code Book'', a survey of the history of cryptography written by Simon Singh and published in 1999.

Dramatic adaptations

Episode four of the 1971 television miniseries '' Elizabeth R'' (titled "Horrible Conspiracies") is devoted to the Babington Plot. It is also depicted in the miniseries ''Elizabeth I'' (2005) and the films ''Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

'' (1971), '' Elizabeth: The Golden Age'' (2007) and ''Mary Queen of Scots'' (2018).

A 45-minute drama entitled ''The Babington Plot'', written by Michael Butt and directed by Sasha Yevtushenko, was broadcast on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

on 2 December 2008 as part of the '' Afternoon Drama''. This drama took the form of a documentary on the first anniversary of the executions, with the story being told from the perspectives of Thomas Salisbury, Robert Poley, Gilbert Gifford and others who, while not conspirators, are in some way connected with the events, all of whom are interviewed by the Presenter (played by Stephen Greif). The cast also included Samuel Barnett as Thomas Salisbury, Burn Gorman as Robert Poley

Robert Poley, or Pooley (fl. 1568– aft. 1602) was an English double agent, government messenger and ''agent provocateur'' employed by members of the Privy Council during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; he was described as "the very genius of ...

, Jonathan Taffler as Thomas Phelippes and Inam Mirza as Gilbert Gifford.

Episode one of the 2017 BBC miniseries ''Elizabeth I's Secret Agents'' (broadcast in the U.S. on PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

in 2018 as ''Queen Elizabeth's Secret Agents'') deals in part with the Babington plot.

See also

*Rising of the North

The Rising of the North of 1569, also called the Revolt of the Northern Earls, Northern Rebellion or the Rebellion of the Earls, was an unsuccessful attempt by Catholicism, Catholic nobles from Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I of En ...

*Ridolfi Plot

The Ridolfi plot was a Catholic plot in 1571 to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. The plot was hatched and planned by Roberto Ridolfi, an international banker who was able to travel between Bruss ...

*Throckmorton Plot

The 1583 Throckmorton Plot was one of a series of attempts by English Roman Catholics to depose Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, then held under house arrest in England. The alleged objective was to facilitate a Sp ...

*History of cryptography

Cryptography, the use of codes and ciphers, began thousands of years ago. Until recent decades, it has been the story of what might be called classical cryptography — that is, of methods of encryption that use pen and paper, or perhaps simple m ...

Notes and references

Further reading

*Gordon-Smith, Alan. ''The Babington Plot''. London: Macmillan (1936) *Guy, John A. ''Queen of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart'' (2005) *Lewis, Jayne Elizabeth. ''The trial of Mary Queen of Scots: a brief history with documents'' (1999) *Pollen, John Hungerford. "Mary Queen of Scots and the Babington plot," ''The Month,'' Volume 10online

(April 1907) pp. 356–365 *Read, Conyers. ''Mr Secretary Walsingham and the policy of Queen Elizabeth'' 3 vols. (1925) *Shepherd, J.E.C. ''The Babington Plot: Jesuit Intrigue in Elizabethan England''. Toronto, Ont.: Wittenburg Publications, 1987. 171 pp. *Williams, Penry. "Babington, Anthony (1561–1586)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004

accessed 18 Sept 2011

*''Military Heritage'' August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 20–23, . *Briscoe, Alexsandra, "Elizabeth's Spy Network", ''BBC History'

online

(17 February 2011)

Primary sources

*Pollen, John Hungerford, ed. "Mary Queen of Scots and the Babington Plot," ''Scottish Historical Society'' 3rd ser., iii (1922), reprints the major documents.External links

{{authority control 1586 in England 1586 in Scotland Espionage scandals and incidents Babington Plot History of cryptography History of Catholicism in England History of Catholicism in Scotland Elizabeth I Mary, Queen of Scots Attempted coups d'état in Europe 1586 in Christianity 16th-century anti-Protestantism 16th-century coups d'état