African-American history started with the forced transportation of

Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

to

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

in the 16th and 17th centuries. The

European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse explored and colonized areas of Europe a ...

, and the resulting

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

, encompassed a large-scale transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. Of the roughly 10–12 million Africans who were sold in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

, either to Europe or the Americas, approximately 388,000 were sent to North America. After arriving in various European colonies in North America, the enslaved Africans were sold to white colonists, primarily to work on

cash crop

A cash crop, also called profit crop, is an Agriculture, agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate a marketed crop from a staple crop ("subsi ...

plantations. A group of enslaved Africans

arrived in the English

Virginia Colony

The Colony of Virginia was a British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776.

The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colony lasted for t ...

in 1619, marking the beginning of

slavery in the colonial history of the United States

The institution of slavery in the European colonization of the Americas, European colonies in North America, which eventually became part of the United States, United States of America, developed due to a combination of factors. Primarily, the ...

; by 1776, roughly 20% of the

British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

n population was of African descent, both

free and enslaved.

During the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, in which the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

gained independence and began to form the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

,

Black soldiers fought on both the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and the

American sides. After the conflict ended, the

Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical and historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the ...

gradually abolished slavery.

However, the population of the

American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is census regions United States Census Bureau. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the ...

, which had an economy dependent on

plantations operation by slave labor, increased their usage of Africans as slaves during the

westward expansion of the United States. During this period, numerous enslaved African Americans escaped into

free states and

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

via the

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. Disputes over slavery between the Northern and Southern states led to the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, in which 178,000 African Americans

served on the

Union side. During the war, President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

issued the

Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery in the U.S., except as punishment for a crime.

After the war ended with a

Confederate defeat, the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

began, in which African Americans living in the South were

granted limited rights compared to their white counterparts. White opposition to these advancements led to most African Americans living in the South to be

disfranchised, and a system of

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

known as the

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

was passed in the Southern states.

Beginning in the early 20th century, in response to poor economic conditions, segregation and

lynchings, over 6 million African Americans, primarily rural, were forced to

migrate out of the South to other regions of the United States in search of opportunity. The

nadir of American race relations

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African-American history and the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century, when racism in the country, and particularly anti-bl ...

led to

civil rights efforts to overturn

discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

and

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

against African Americans. In 1954, these efforts coalesced into a

broad unified movement led by civil rights activists such as

Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparke ...

and

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

This succeeded in persuading the

federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

to pass the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, which outlawed racial discrimination.

The

2020 United States census reported that 46,936,733 respondents identified as African Americans, forming roughly 14.2% of the

American population. Of those, over 2.1 million

immigrated to the United States as citizens of modern African states.

African Americans have made major contributions to the

culture of the United States

The culture of the United States encompasses various social behaviors, institutions, and Social norm, norms, including forms of Languages of the United States, speech, American literature, literature, Music of the United States, music, Visual a ...

, including

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

,

cinema and

music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

.

Enslavement

African origins

African Americans are the descendants of

Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

who were forced into slavery and sold after they were captured by other tribes during African wars or raids, and were brought to America by Europeans as part of the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

. The major ethnic groups that the enslaved Africans belonged to included the

Bakongo

The Kongo people (also , singular: or ''M'kongo; , , singular: '') are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have li ...

,

Igbo,

Mandinka,

Wolof,

Akan,

Fon,

Yoruba, and

Makua, among many others.

[Carson, Clayborne, Emma Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary Nash. ''The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans''. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2011. ] Once they were enslaved and sent to the Americas, these different peoples had European standards and beliefs forced upon them, causing them to do away with tribal differences and forge a new common culture that was a

creolization

Creolization is the process through which creole languages and cultures emerge. Creolization was first used by linguists to explain how contact languages become creole languages, but now scholars in other social sciences use the term to describe ...

of their original cultures and European cultures. People who belonged to specific African ethnic groups were more sought after and became more dominant in numbers than people who belonged to other African ethnic groups in certain regions of the land that is now the United States.

Studies of contemporary documents reveal seven regions from which Africans were sold or taken during the Atlantic slave trade. These regions were:

*

Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

(present-day

Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and

The Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

) encompassing the coast from the

Senegal River

The Senegal River ( or "Senegal" - compound of the Serer term "Seen" or "Sene" or "Sen" (from Roog Seen, Supreme Deity in Serer religion) and "O Gal" (meaning "body of water")); , , , ) is a river in West Africa; much of its length mark ...

to the

Casamance River, where captives as far away as the Upper and Middle

Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mali, Nige ...

Valley were sold;

* The

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

region included territory from the

Casamance to the

Assinie in the modern countries of

Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau, officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, is a country in West Africa that covers with an estimated population of 2,026,778. It borders Senegal to Guinea-Bissau–Senegal border, its north and Guinea to Guinea–Guinea-Bissau b ...

,

Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

,

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

,

Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

, and

Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest city and ...

;

* The

Gold Coast region consisted of mainly modern

Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

;

* The

Bight of Benin

The Bight of Benin, or Bay of Benin, is a bight in the Gulf of Guinea area on the western African coast that derives its name from the historical Kingdom of Benin.

Geography

The Bight of Benin was named after the Kingdom of Benin. It extends ea ...

region stretched from the

Volta River

The Volta River (, , ) is the main Drainage system (geomorphology), river system in the West African country of Ghana. It flows south into Ghana from the Bobo-Dioulasso Department, Bobo-Dioulasso highlands of Burkina Faso.

The three main part ...

to the

Benue River

Benue River (), previously known as the Chadda River or Tchadda, is a major tributary of the Niger River. The size of its catchment basin is 319,000 km2 (123,000 sq mi). Almost its entire length of Approximation, approximately is navigable dur ...

in modern

Togo

Togo, officially the Togolese Republic, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to Ghana–Togo border, the west, Benin to Benin–Togo border, the east and Burkina Faso to Burkina Faso–Togo border, the north. It is one of the le ...

,

Benin

Benin, officially the Republic of Benin, is a country in West Africa. It was formerly known as Dahomey. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north-west, and Niger to the north-east. The majority of its po ...

, and southwestern

Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

;

* The

Bight of Biafra

The Bight of Biafra, also known as the Bight of Bonny, is a bight off the west- central African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea. This "bight" has also sometimes been erroneously referred to as the "Bight of Africa" because ...

extended from southeastern

Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

through

Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

into

Gabon

Gabon ( ; ), officially the Gabonese Republic (), is a country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, on the equator, bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, the Republic of the Congo to the east and south, and ...

;

* West Central Africa, the largest region, included the

Congo and

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

; and

* East and Southeast Africa, the region of Mozambique-Madagascar included the modern countries of

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

, parts of

Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, and

Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

.

The largest origin of Africans transported as slaves across the Atlantic Ocean for the New World was West Africa. Some West Africans were skilled iron workers and were therefore able to make tools that aided in their agricultural labor. While there were many unique tribes with their own customs and religions, by the 15th century many of the tribes had embraced Islam. Those villages in West Africa which were lucky enough to be in good conditions for growth and success, prospered. They also contributed their success to the slave trade for their own benefit.

Origins and percentages of African Americans imported to the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

,

New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(1700–1820):

In the account of

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist. According to his memoir, he was from the village of Essaka in present day southern Nigeria. Enslaved as a child in ...

, he described the process of being transported to the colonies and being on the slave ships as a horrific experience. On the ships, the enslaved Africans were separated from their family long before they boarded the ships.

Once aboard the ships the captives were then segregated by gender.

Under the deck, the enslaved Africans were cramped and did not have enough space to walk around freely. Enslaved males were generally kept in the ship's hold, where they experienced the worst of crowding.

The captives stationed on the floor beneath low-lying bunks could barely move and spent much of the voyage pinned to the floorboards, which could, over time, wear the skin on their elbows down to the bone.

Due to the lack of basic hygiene, malnourishment, and dehydration diseases spread wildly and death was common.

The women on the ships were often raped by the crewmen.

Women and children were often kept in rooms set apart from the main hold to give crewmen access to the women.

However, these rooms also gave enslaved women better access to information on the ship's crew, fortifications, and daily routine, but little opportunity to communicate this to the men confined in the ship's hold.

Women instigated, among other attempts at mutiny, a 1797 insurrection aboard the

slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting Slavery, slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea ( ...

''Thomas'' by stealing weapons and passing them to the men below as well as engaging in hand-to-hand combat with the ship's crew.

Enslaved males were the most likely candidates to mutiny but were only able to at times they were on deck.

While rebellions did not happen often, they were usually unsuccessful. In order for the crew members to keep the enslaved Africans under control and prevent future rebellions, the crews were often twice as large and members would instill fear into the enslaved Africans through brutality and harsh punishments.

It took about six months from the time of capture for enslaved Africans to arrive on the plantations of their European masters.

Africans were completely cut off from their families, home, and community life and were forced to adjust to a new way of life.

Colonial era

Some Africans assisted the Spanish and the Portuguese during their early exploration and conquest of the Americas. In the 16th century some Black explorers settled in the Mississippi valley and in the areas that became South Carolina and New Mexico. The most celebrated Black explorer of the Americas was

Estéban, who traveled through the Southwest in the 1530s.

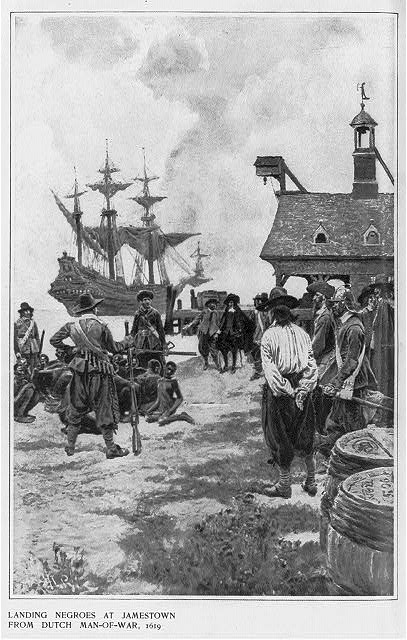

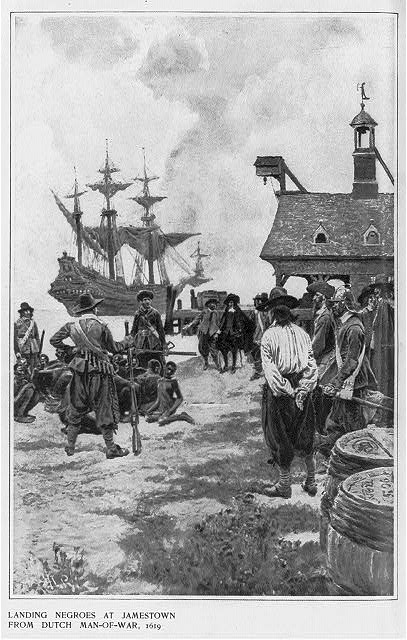

In 1619, the

first captive Africans were brought and sold via a Dutch slave ship in

Point Comfort (today

Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

in

Hampton, Virginia

Hampton is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. The population was 137,148 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, seve ...

). Colonizers in Virginia treated these captives as

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

and released them after a number of years. This practice was gradually abandoned in favor of the system of chattel slavery used in the

Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

because the colonizers realized when servants were freed, they became competition for resources. Additionally, releasing servants led to Europeans desiring to replace them, which was additional labor.

This, combined with the ambiguous nature of the social status of African people and the difficulty in using any other group of people as forced servants, led to the choice of subjugating African people into slavery.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

was the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641. Other colonies followed suit by passing laws that made slave status heritable and made non-Christian imported servants slaves for life.

By 1700, there were 25,000 enslaved Black people in the North American mainland colonies, forming roughly 10% of the population. Some enslaved Black people had been directly transported from Africa (most of them were from 1518 to the 1850s), but initially, in the very early stages of the

European colonization of North America, occasionally they had been transported via the West Indies in small groups after being forced to work under harsh conditions on the islands.

[John Murrin, Paul Johnson, James McPherson, Alice Fahs, Gary Gerstle]

"Expansion, Immigration, and Regional Differentiation"

in ''Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Volume 1: To 1877'', Cengage Learning, 2011, p. 108. Concurrently, many were born to enslaved Africans and their descendants, and thus were native-born on the North American mainland. Their legal status was codified into law with the Virginia Statutes: ACT XII of 1662, proclaiming all children upon birth would inherit the same status of enslavement as their mother.

As European colonists engaged in aggressive

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

, claiming and clearing more land— via the displacement of

Native Americans— for large-scale farming. Plantations were constructed, and in the 1660s enslavement and transport of Africans rapidly increased. The slave trade from the West Indies proved insufficient to meet demand in the now fast-growing North American slave market. Additionally, most North American buyers of enslaved people no longer wanted to purchase enslaved people who had already endured slavery in the West Indies—by now they were either harder to obtain, too expensive, undesirable, or more often, they had been exhausted in many ways by the brutality of the islands'

sugar plantations

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tobac ...

. From the 1680s onward, the majority of enslaved Africans imported into North America were directly from Africa, and most of them were sent to ports located in what is now the Southern U.S., particularly in the present-day states of Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana.

Black population in the 18th century

The population of enslaved African Americans in North America grew rapidly during the 18th and early 19th centuries due to a variety of factors, including a lower prevalence of tropic diseases and rape of black women by white men. Colonial society was divided over the religious and moral implications of slavery, though it remained legal in each of the Thirteen Colonies until the American Revolution. Slavery led to a gradual shift between the American South and North, both before and after independence, as the comparatively more urbanized and industrialized North required fewer slaves than the South.

By the 1750s, the native-born enslaved population of African descent outnumbered that of the African-born enslaved. By the time of the American Revolution, several Northern states were considering the abolition of slavery. However some Southern colonies, such as Virginia, had produced such large and self-sustaining native-born enslaved Black populations that they stopped taking indirect imports of enslaved Africans altogether. Other colonies such as Georgia and South Carolina still relied on steady enslavement of people to keep up with the ever-growing demand for agricultural labor among the burgeoning plantation economies. These colonies continued to import enslaved Africans until the trade was outlawed in 1808, save for a temporary lull during the

Revolutionary War.

South Carolina's Black population remained very high for most of the eighteenth century due to the continued import of enslaved Africans, with Blacks outnumbering whites three-to-one. In contrast, Virginia had a consistent white majority despite its significant Black enslaved population. It was said that in the eighteenth century, the

colony South Carolina resembled an "extension of

West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

".

American Revolution and early United States

The latter half of the 18th century was a time of significant political upheaval on the North American continent. In the midst of cries for independence from

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

rule, many pointed out the hypocrisy inherent in colonial slaveholders' demands for freedom. The

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, a document which would become a

manifesto

A manifesto is a written declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party, or government. A manifesto can accept a previously published opinion or public consensus, but many prominent ...

for human rights and personal freedom around the world, was written by

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, a man who owned over 200 enslaved people. Other Southern statesmen were also major slaveholders. The

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

considered freeing enslaved people to assist with the war effort, but they also removed language from the Declaration of Independence that included the promotion of slavery amongst the offenses of

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. A number of free Black people, most notably

Prince Hall

Prince Hall (December 7, 1807) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and leader in the Free negro, free black community in Boston. He founded Prince Hall Freemasonry and lobbied for Right to education, education rights ...

—founder of

Prince Hall Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry is a branch of North American Freemasonry created for African Americans, founded by Prince Hall on September 29, 1784. Prince Hall Freemasonry is the oldest and largest (300,000+ initiated members) predominantly African-A ...

—submitted

petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to an officia ...

s which called for abolition, but these were largely ignored.

This did not deter Black people, free and enslaved, from participating in the Revolution.

Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks ( – March 5, 1770) was an American whaler, sailor, and stevedore of African and Native American descent who is traditionally regarded as the first person killed in the Boston Massacre, and as a result the first American kil ...

, a free Black tradesman, was the first casualty of the

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre, known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street, was a confrontation, on March 5, 1770, during the American Revolution in Boston in what was then the colonial-era Province of Massachusetts Bay.

In the confrontati ...

and of the ensuing

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. 5,000 Black people, including Prince Hall, fought in the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

. Many fought side by side with

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

soldiers at the

battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 were the first major military actions of the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot militias from America's Thirteen Co ...

and at

Bunker Hill. However, upon

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

's ascension to commander of the Continental Army in 1775, the additional recruitment of Black people was forbidden.

Approximately 5,000 free African-American men helped the American Colonists in their struggle for freedom. One of these men,

Agrippa Hull, fought in the American Revolution for over six years. He and the other African-American soldiers fought in order to improve their white neighbor's views of them and advance their own fight of freedom.

By contrast, the British and

Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

offered

emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure Economic, social and cultural rights, economic and social rights, civil and political rights, po ...

to any enslaved person owned by a

Patriot who was willing to join the Loyalist forces.

Lord Dunmore, the

Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. The Governor (United States), governor is head of the Government_of_Virginia#Executive_branch, executive branch ...

, recruited 300 African-American men into his

Ethiopian regiment within a month of making this proclamation. In South Carolina 25,000 enslaved people, more than one-quarter of the total, escaped to join and fight with the British, or fled for freedom in the uproar of war. Thousands of enslaved people also escaped in Georgia and Virginia, as well as New England and New York. Well-known African Americans who fought for the British include

Colonel Tye and

Boston King.

Thomas Peters was one of the large numbers of African Americans who

fought for the British. Peters was born in present-day Nigeria and belonged to the Yoruba tribe, and ended up being captured and sold into slavery in

French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana ( ; ) refers to two distinct regions:

* First, to Louisiana (New France), historic French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by Early Modern France, France during the 17th and 18th ...

. Sold again, he was enslaved in

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

and escaped his master's farm in order to receive Lord Dunmore's promise of freedom. Peters had fought for the British throughout the war. When the war finally ended, he and other African Americans who fought on the losing side were taken to Nova Scotia. Here, they encountered difficulty farming the small plots of lands they were granted. They also did not receive the same privileges and opportunities as the white

Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

had. Peters sailed to London in order to complain to the government. "He arrived at a momentous time when

English abolitionists

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

were pushing a bill through Parliament to charter the

Sierra Leone Company

The Sierra Leone Company was the corporate body involved in founding the Freetown, second British colony in Africa on 11 March 1792 through the resettlement of Black Loyalists who had initially been settled in Nova Scotia (the Nova Scotian Settler ...

and to grant it trading and settlement rights on the West African coast." Peters and the other African Americans on Nova Scotia left for

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

in 1792. Peters died soon after they arrived, but the other members of his party lived on in their new home where they formed the

Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.

[ https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1991_num_31_121_2116][ Journal of Sierra Leone Studies, Vol. 3; Edition 1, 2014 https://www.academia.edu/40720522/A_Precis_of_Sources_relating_to_genealogical_research_on_the_Sierra_Leone_Krio_people][, originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).]

American independence

The colonists eventually won the war and the United States was recognized as a sovereign nation. In the provisional treaty, they demanded the return of property, including enslaved people. Nonetheless, the British helped up to 3,000 documented African Americans to leave the country for

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

,

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

and Britain rather than be returned to slavery.

The

Constitutional Convention of 1787 sought to define the foundation for the government of the newly formed United States of America. The

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

set forth the ideals of freedom and equality while providing for the continuation of the institution of slavery through the

fugitive slave clause and the

three-fifths compromise

The Three-fifths Compromise, also known as the Constitutional Compromise of 1787, was an agreement reached during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention over the inclusion of slaves in counting a state's total population. This count ...

. Additionally, free Black people's rights were also restricted in many places. Most were denied the right to vote and were excluded from public schools. Some Black people sought to fight these contradictions in court. In 1780,

Elizabeth Freeman and

Quock Walker used language from the new

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

constitution that declared all men were born free and equal in

freedom suits to gain release from slavery. A free Black businessman in Boston named

Paul Cuffe

Paul Cuffe, also known as Paul Cuffee (January 17, 1759 – September 7, 1817) was an African American and Wampanoag businessman, Whaling in the United States, whaler and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. Born Free negro, free int ...

sought to be excused from paying taxes since he had no voting rights.

In the Northern states, the revolutionary spirit did help African Americans. Beginning in the 1750s, there was widespread sentiment during the American Revolution that slavery was a social evil (for the country as a whole and for the whites) that should eventually be abolished. All the Northern states passed emancipation acts between 1780 and 1804; most of these arranged for gradual emancipation and a special status for

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

, so there were still a dozen "permanent apprentices" into the 19th century. In 1787 Congress passed the

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

and barred slavery from the large Northwest Territory. In 1790, there were more than 59,000 free Black people in the United States. By 1810, that number had risen to 186,446. Most of these were in the North, but Revolutionary sentiments also motivated Southern slaveholders.

For 20 years after the Revolution, more Southerners also freed enslaved people, sometimes by manumission or in wills to be accomplished after the slaveholder's death. In the Upper South, the percentage of free Black people rose from about 1% before the Revolution to more than 10% by 1810.

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

and

Moravians

Moravians ( or Colloquialism, colloquially , outdated ) are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, who speak the Moravian dialects of Czech language, Czech or Czech language#Common Czech, Common ...

worked to persuade slaveholders to free families. In Virginia, the number of free Black people increased from 10,000 in 1790 to nearly 30,000 in 1810, but 95% of Black people were still enslaved. In Delaware, three-quarters of all Black people were free by 1810. By 1860, just over 91% of Delaware's Black people were free, and 49.1% of those in Maryland.

Among the successful free men was

Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker (November 9, 1731October 19, 1806) was an American Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author. A Land tenure, landowner, he also worked as a surveying, surveyor and farmer.

Born in Baltimore Co ...

, a

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

astronomer, mathematician, almanac author, surveyor, and farmer, who in 1791 assisted in the initial survey of the boundaries of the future

District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

. Despite the challenges of living in the new country, most free Black people fared far better than the nearly 800,000 enslaved Blacks. Even so, many considered

emigrating to Africa.

Antebellum period

As the United States grew, the institution of slavery became more entrenched in the

southern states, while northern states began to

abolish it.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

was the first, in 1780 passing an act for gradual abolition.

Slaves were often sexually abused and raped by their white slave owners. White people often forced slaves to work even when sick. Slaves weren’t protected from being harassed, sexually stalked or raped by their white masters. Black slaves were also whipped, killed, tortured and had their limbs amputated.

A number of events continued to shape views on slavery. One of these events was the

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

, which was the only slave revolt that led to an independent country. Many slave owners fled to the United States with tales of horror and massacre that alarmed Southern whites.

The invention of the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

in the 1790s allowed the cultivation of short staple cotton, which could be grown in much of the Deep South, where warm weather and proper soil conditions prevailed. The industrial revolution in Europe and New England generated a heavy demand for cotton for cheap clothing, which caused an enormous demand for slave labor to develop new

cotton plantations. There was a 70% increase in the number of enslaved people in the United States in only 20 years. They were overwhelmingly concentrated on plantations in the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, and moved west as old cotton fields lost their productivity and new lands were purchased. Unlike the Northern States who put more focus into manufacturing and commerce, the South was heavily dependent on agriculture. Southern political economists at this time supported the institution by concluding that nothing was inherently contradictory about owning people and that a future of slavery existed even if the South were to industrialize. Racial, economic, and political turmoil reached an all-time high regarding slavery up to the events of the Civil War.

In 1807, at the urging of President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, Congress abolished the importation of enslaved workers. While American Black people celebrated this as a victory in the fight against slavery, the ban increased the internal trade of enslaved people. Changing agricultural practices in the Upper South from tobacco to mixed farming decreased labor requirements, and enslaved people were sold to traders for the developing Deep South. In addition, the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to al ...

allowed any Black person to be claimed as a runaway unless a White person testified on their behalf. A number of free Black people, especially

indentured

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

children, were

kidnap

Kidnapping or abduction is the unlawful abduction and confinement of a person against their will, and is a crime in many jurisdictions. Kidnapping may be accomplished by use of force or fear, or a victim may be enticed into confinement by frau ...

ped and sold into slavery with little or no hope of rescue. By 1819 there were exactly 11 free and 11 slave states, which increased

sectionalism

Sectionalism is loyalty to one's own region or section of the country, rather than to the country as a whole.

Sectionalism occurs in many countries, such as in the United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom

Sectionalism occurs most notably in the co ...

. Fears of an imbalance in Congress led to the 1820

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

that required states to be admitted to the union in pairs, one slave and one free.

In 1831, a

rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

occurred under the leadership of

Nat Turner, that lasted four days. During the rebellion, which had been the most deadly in the United States, 55 white people were killed, while 120 black people, most unaffiliated with the rebellion, were killed in a retaliation by soldiers aided by local residents angry at the killings. This led to a fear larger scale rebellions would occur.

In 1850, after winning the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, a problem gripped the nation: what to do about the territories won from Mexico. Henry Clay, the man behind the

compromise of 1820, once more rose to the challenge, to craft the

compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. In this compromise the territories of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada would be organized but the issue of slavery would be decided later. Washington D.C. would abolish the slave trade but not slavery itself. California would be admitted as a free state but the South would receive a new

fugitive slave act which required Northerners to return enslaved people who escaped to the North to their owners. The compromise of 1850 would maintain a shaky peace until the election of Lincoln in 1860.

In 1851 the battle between enslaved people and slave owners was met in

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County (; ), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 United States ...

.

The Christiana Riot demonstrated the growing conflict between

states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

and Congress on the issue of slavery.

Abolitionism

Abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

in Britain and the United States in the 1840–1860 period developed large, complex campaigns against slavery.

According to Patrick C. Kennicott, the largest and most effective abolitionist speakers were Black people who spoke before the countless local meetings of the

National Negro Conventions. They used the traditional arguments against slavery, protesting it on moral, economic, and political grounds. Their role in the antislavery movement not only aided the abolitionist cause but also was a source of pride to the Black community.

In 1852,

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

published a novel that changed how many would view slavery. ''

Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

'' tells the story of the life of an enslaved person and the brutality that is faced by that life day after day. It would sell over 100,000 copies in its first year. The popularity of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' would solidify the North in its opposition to slavery, and press forward the abolitionist movement. President Lincoln would later invite Stowe to the White House in honor of this book that changed America.

In 1856

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

, a Massachusetts congressmen and antislavery leader,

was assaulted and nearly killed on the House floor by Preston Brooks of South Carolina. Sumner had been delivering an abolitionist speech to Congress when Brooks attacked him. Brooks received praise in the South for his actions while Sumner became a political icon in the North. Sumner later returned to the Senate, where he was a leader of the

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

in ending slavery and legislating equal rights for freed slaves.

Over 1 million enslaved people were moved from the older seaboard slave states, with their declining economies, to the rich cotton states of the southwest; many others were sold and moved locally. Ira Berlin (2000) argues that this

Second Middle Passage shredded the planters' paternalist pretenses in the eyes of Black people and prodded enslaved people and free Black people to create a host of oppositional ideologies and institutions that better accounted for the realities of endless deportations, expulsions, and flights that continually remade their world. Benjamin Quarles' work ''Black Abolitionists'' provides the most extensive account of the role of Black abolitionists in the American anti-slavery movement.

The Black community

Black people generally settled in cities, creating the core of Black community life in the region. They established churches and fraternal orders. Many of these early efforts were weak and they often failed, but they represented the initial steps in the evolution of Black communities.

During the early Antebellum period, the creation of free Black communities began to expand, laying out a foundation for African Americans' future. At first, only a few thousand African Americans had their freedom. As the years went by, the number of Blacks being freed expanded tremendously, building to 233,000 by the 1820s. They sometimes sued to gain their freedom or purchased it. Some slave owners freed their bondspeople and a few state legislatures abolished slavery.

African Americans tried to take the advantage of establishing homes and jobs in the cities. During the early 1800s free Black people took several steps to establish fulfilling work lives in urban areas. The rise of industrialization, which depended on power-driven machinery more than human labor, might have afforded them employment, but many owners of textile mills refused to hire Black workers. These owners considered whites to be more reliable and educable. This resulted in many Black people performing unskilled labor. Black men worked as

stevedore

A dockworker (also called a longshoreman, stevedore, docker, wharfman, lumper or wharfie) is a waterfront manual laborer who loads and unloads ships.

As a result of the intermodal shipping container revolution, the required number of dockwork ...

s,

construction worker

A construction worker is a person employed in the physical construction of the built environment and its infrastructure.

Definitions

By some definitions, construction workers may be engaged in manual labour as unskilled or semi-skilled workers ...

, and as cellar-, well- and grave-diggers. As for Black women workers, they worked as servants for white families. Some women were also cooks, seamstresses, basket-makers, midwives, teachers, and nurses.

Black women worked as washerwomen or domestic servants for the white families. Some cities had independent Black seamstresses, cooks, basketmakers, confectioners, and more.

While the African Americans left the thought of slavery behind, they made a priority to reunite with their family and friends. The cause of the Revolutionary War forced many Black people to migrate to the west afterwards, and the scourge of poverty created much difficulty with housing. African Americans competed with the Irish and Germans in jobs and had to share space with them.

While the majority of free Black people lived in poverty, some were able to establish successful businesses that catered to the Black community.

Racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their Race (human categorization), race, ancestry, ethnicity, ethnic or national origin, and/or Human skin color, skin color and Hair, hair texture. Individuals ...

often meant that Black people were not welcome or would be mistreated in White businesses and other establishments. To counter this, Black people like

James Forten

James Forten (September 2, 1766March 4, 1842) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and businessman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A free-born African American, he became a sailmaker after the American Revolutionary War. ...

developed their own communities with Black-owned businesses. Black doctors, lawyers, and other businessmen were the foundation of the Black

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

.

Many Black people organized to help strengthen the Black community and continue the fight against slavery. One of these organizations was the American Society of Free Persons of Colour, founded in 1830. This organization provided social aid to poor Black people and organized responses to political issues. Further supporting the growth of the Black Community was the

Black church

The Black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian denominations and congregations in the United States that predominantly minister to, and are led by, African Americans, ...

, usually the first community institution to be established. Starting in the early 1800s with the

African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan theology, Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexionalism, connexional polity. It ...

,

African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and other churches, the Black church grew to be the focal point of the Black community. The Black church was both an expression of community and unique African-American spirituality, and a reaction to European American discrimination. The church also served as neighborhood centers where free Black people could celebrate their African heritage without intrusion by white detractors.

The church was the center of the Black communities, but it was also the center of education. Since the church was part of the community and wanted to provide education; they educated the freed and enslaved Black people. At first, Black preachers formed separate congregations within the existing

denominations, such as social clubs or literary societies. Because of discrimination at the higher levels of the church hierarchy, some Black people like

Richard Allen (bishop) simply founded separate Black denominations.

Free Black people also established Black churches in the South before 1800. After the

Great Awakening

The Great Awakening was a series of religious revivals in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the late 20th cent ...

, many Black people joined the

Baptist Church

Baptists are a denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers ( believer's baptism) and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches generally subscribe to the doctrines of ...

, which allowed for their participation, including roles as elders and preachers. For instance,

First Baptist Church and

Gillfield Baptist Church of

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458 with a majority bla ...

, both had organized congregations by 1800 and were the first Baptist churches in the city. Petersburg, an industrial city, by 1860 had 3,224 free Black people (36% of Black people, and about 26% of all free persons), the largest population in the South. In Virginia, free Black people also created communities in

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

and other towns, where they could work as artisans and create businesses.

Others were able to buy land and farm in frontier areas further from white control.

The Black community also established schools for Black children, since they were often banned from entering public schools. Richard Allen organized the first Black Sunday school in America; it was established in Philadelphia during 1795.

Then five years later, the priest

Absalom Jones established a school for Black youth.

Black Americans regarded education as the surest path to economic success, moral improvement and personal happiness. Only the sons and daughters of the Black middle class had the luxury of studying.

Haiti's effect on slavery

The revolt of enslaved Haitians against their white slave owners, which began in 1791 and lasted until 1801, was a primary source of fuel for both enslaved people and abolitionists arguing for the freedom of Africans in the U.S. In the 1833 edition of

''Nile's Weekly Register'' it is stated that freed Black people in Haiti were better off than their Jamaican counterparts, and the positive effects of

American Emancipation are alluded to throughout the paper. These anti-slavery sentiments were popular among both white abolitionists and African-American slaves. Enslaved people rallied around these ideas with rebellions against their masters as well as white bystanders during the

Denmark Vesey Conspiracy of 1822 and the

Nat Turner's Rebellion

Nat Turner's Rebellion, historically known as the Southampton Insurrection, was a slave rebellion that took place in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Led by Nat Turner, the rebels, made up of enslaved African Americans, killed b ...

of 1831. Leaders and plantation owners were also very concerned about the consequences Haiti's revolution would have on early America. Thomas Jefferson, for one, was wary of the "instability of the West Indies", referring to Haiti.

''Dred Scott v. Sandford''

Dred Scott

Dred Scott ( – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, in the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' case ...

was an enslaved man whose owner had taken him to live in the free state of Illinois. After his owner's death, Dred Scott sued in court for his freedom on the basis of his having lived in a free state for a long period. The Black community received an enormous shock with the Supreme Court's "Dred Scott" decision in March 1857. Black people were not American citizens and could never be citizens, the court said in a decision roundly denounced by the Republican Party as well as the abolitionists. Because enslaved people were "property, not people", by this ruling they could not sue in court. The decision was finally reversed by the Civil Rights Act of 1865. In what is sometimes considered mere

obiter dictum

''Obiter dictum'' (usually used in the plural, ''obiter dicta'') is a Latin phrase meaning "said in passing",'' Black's Law Dictionary'', p. 967 (5th ed. 1979). that is, any remark in a legal opinion that is "said in passing" by a judge or arbitr ...

the Court went on to hold that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories because enslaved people are personal property and the

Fifth Amendment to the Constitution protects property owners against deprivation of their property without due process of law. Although the Supreme Court has never explicitly overruled the Dred Scott case, the Court stated in the

Slaughter-House Cases

The ''Slaughter-House Cases'', 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision which ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only protects the legal rights t ...

that at least one part of it had already been overruled by the

Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, which begins by stating, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

Lynchings

Black men were often lynched by white men because they were thought to be a threat to white womanhood. The stereotype of Black men being dangerous rapists with a large penis with a lustful nature bent on white women was prevalent in the South.

Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was an African American youth, who was 14 years old when he was abducted and Lynching in the United States, lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of offending a white woman, ...

was lynched for allegedly flirting with a white woman in Mississippi.

American Civil War and emancipation

The

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

was an executive order issued by President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

on January 1, 1863. In a single stroke it changed the legal status, as recognized by the U.S. government, of 3 million enslaved people in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free." Its practical effect was that as soon as an enslaved person escaped from slavery, by running away or through advances of federal troops, the enslaved person became legally and actually free. The owners were never compensated. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their enslaved people as far as possible out of reach of the Union army. By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all the designated enslaved people.

About 200,000 free Black people and former enslaved people served in the Union Army and Navy, thus providing a basis for a claim to full citizenship. The dislocations of war and Reconstruction had a severe negative impact on the Black population, with much sickness and death.

Reconstruction

The

Civil Rights Act of 1866 made Black people full U.S. citizens (and this repealed the ''Dred Scott'' decision). In 1868, the

14th Amendment granted full U.S. citizenship to African Americans. The

15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, extended the right to vote to Black males. The

Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was a U.S. government agency of early post American Civil War Reconstruction, assisting freedmen (i.e., former enslaved people) in the ...

was an important institution established to create social and economic order in Southern states.

After the Union victory over the Confederacy, a brief period of Southern Black progress, called Reconstruction, followed. During Reconstruction, the states that had seceded were readmitted into the Union. From 1865 to 1877, under the protection of Union troops, some strides were made toward equal rights for African Americans. Southern Black men began to vote and they were also elected to serve in the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

as well as in local offices such as the office of sheriff. The safety which was provided by the troops did not last long, however, and white Southerners frequently terrorized Black voters. Coalitions of white and Black Republicans passed bills in order to establish the first public school systems in most states of the South, although sufficient funding was hard to find. Black people established their own churches, towns, and businesses. Tens of thousands migrated to Mississippi for the chance to clear and own their own land, as 90 percent of the bottomlands were undeveloped. By the end of the 19th century, two-thirds of the farmers who owned land in the

Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazo ...

bottomlands were Black.