aeronaut on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study,

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study,

Attempts to fly without any real aeronautical understanding have been made from the earliest times, typically by constructing wings and jumping from a tower with crippling or lethal results.

Wiser investigators sought to gain some rational understanding through the study of bird flight. Medieval

Attempts to fly without any real aeronautical understanding have been made from the earliest times, typically by constructing wings and jumping from a tower with crippling or lethal results.

Wiser investigators sought to gain some rational understanding through the study of bird flight. Medieval

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with  From the mid-18th century the

From the mid-18th century the

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

''Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy'', 1809–1810. (Via

Raw text

. Retrieved: 30 May 2010. In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air." He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: ''

During the 19th century Cayley's ideas were refined, proved and expanded on, culminating in the works of

During the 19th century Cayley's ideas were refined, proved and expanded on, culminating in the works of

Aeronautics may be divided into three main branches,

Aeronautics may be divided into three main branches,

Aeronautical engineering

, University of Glasgow.

A major part of aeronautical engineering is

Aeronautics: A Class Text

', via

Aviation Terminology

Jeppesen The AVIATION DICTIONARY for pilots and aviation technicians

DTIC ADA032206: Chinese-English Aviation and Space Dictionary

*

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study,

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design

A design is the concept or proposal for an object, process, or system. The word ''design'' refers to something that is or has been intentionally created by a thinking agent, and is sometimes used to refer to the inherent nature of something ...

, and manufacturing of air flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

-capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

and rockets within the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

.

While the term originally referred solely to ''operating'' the aircraft, it has since been expanded to include technology, business, and other aspects related to aircraft.

The term "aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' include fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air aircraft such as h ...

" is sometimes used interchangeably with aeronautics, although "aeronautics" includes lighter-than-air

A lifting gas or lighter-than-air gas is a gas that has a density lower than normal atmospheric gases and rises above them as a result, making it useful in lifting lighter-than-air aircraft. Only certain lighter-than-air gases are suitable as lift ...

craft such as airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

s, and includes ballistic vehicles while "aviation" technically does not.

A significant part of aeronautical science is a branch of dynamics called aerodynamics

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

, which deals with the motion of air and the way that it interacts with objects in motion, such as an aircraft.

History

Early ideas

Attempts to fly without any real aeronautical understanding have been made from the earliest times, typically by constructing wings and jumping from a tower with crippling or lethal results.

Wiser investigators sought to gain some rational understanding through the study of bird flight. Medieval

Attempts to fly without any real aeronautical understanding have been made from the earliest times, typically by constructing wings and jumping from a tower with crippling or lethal results.

Wiser investigators sought to gain some rational understanding through the study of bird flight. Medieval Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

scientists such as Abbas ibn Firnas

Abū al-Qāsim ʿAbbās ibn Firnās ibn Wardūs al-Tākurnī (; c. 809/810 – 887 CE), known as ʿAbbās ibn Firnās () was an Andalusi polymath: Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A C ...

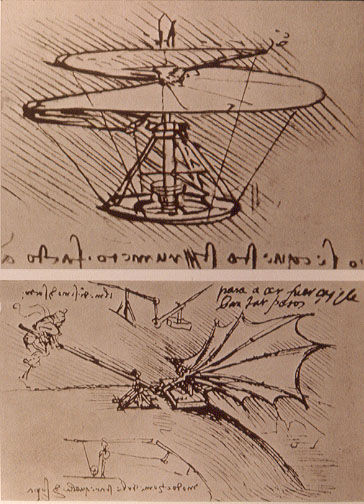

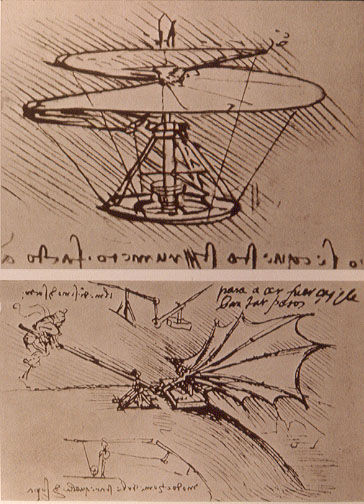

also made such studies. Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", ''Technology and Culture'' 2 (2), p. 97–111 00f./ref> The founders of modern aeronautics, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

in the Renaissance and Cayley in 1799, both began their investigations with studies of bird flight.

Man-carrying kites are believed to have been used extensively in ancient China. In 1282 the Italian explorer Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

described the Chinese techniques then current.Pelham, D.; ''The Penguin book of kites'', Penguin (1976) The Chinese also constructed small hot air balloons, or lanterns, and rotary-wing toys.

An early European to provide any scientific discussion of flight was Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

, who described principles of operation for the lighter-than-air balloon

A balloon is a flexible membrane bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, or air. For special purposes, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), ...

and the flapping-wing ornithopter, which he envisaged would be constructed in the future. The lifting medium for his balloon would be an "aether" whose composition he did not know.

In the late fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci followed up his study of birds with designs for some of the earliest flying machines, including the flapping-wing ornithopter and the rotating-wing helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which Lift (force), lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning Helicopter rotor, rotors. This allows the helicopter to VTOL, take off and land vertically, to hover (helicopter), hover, and ...

. Although his designs were rational, they were not based on particularly good science. Many of his designs, such as a four-person screw-type helicopter, have severe flaws. He did at least understand that "An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object." ( Newton would not publish the Third law of motion until 1687.) His analysis led to the realisation that manpower alone was not sufficient for sustained flight, and his later designs included a mechanical power source such as a spring. Da Vinci's work was lost after his death and did not reappear until it had been overtaken by the work of George Cayley

Sir George Cayley, 6th Baronet (27 December 1773 – 15 December 1857) was an English engineer, inventor, and aviator. He is one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him to be the first true scientific ...

.

Balloon flight

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's experiments in which he showed that air has weight. Around 1650 Cyrano de Bergerac wrote some fantasy novels in which he described the principle of ascent using a substance (dew) he supposed to be lighter than air, and descending by releasing a controlled amount of the substance. Francesco Lana de Terzi

Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631 in Brescia, Lombardy – 22 February 1687, in Brescia, Lombardy) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician, naturalist and aeronautics pioneer. Having been professor of physics and mathematics at Brescia, he fi ...

measured the pressure of air at sea level and in 1670 proposed the first scientifically credible lifting medium in the form of hollow metal spheres from which all the air had been pumped out. These would be lighter than the displaced air and able to lift an airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

. His proposed methods of controlling height are still in use today; by carrying ballast which may be dropped overboard to gain height, and by venting the lifting containers to lose height. In practice de Terzi's spheres would have collapsed under air pressure, and further developments had to wait for more practicable lifting gases.

From the mid-18th century the

From the mid-18th century the Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the Communes o ...

in France began experimenting with balloons. Their balloons were made of paper, and early experiments using steam as the lifting gas were short-lived due to its effect on the paper as it condensed. Mistaking smoke for a kind of steam, they began filling their balloons with hot smoky air which they called "electric smoke" and, despite not fully understanding the principles at work, made some successful launches and in 1783 were invited to give a demonstration to the French ''Académie des Sciences''.

Meanwhile, the discovery of hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

led Joseph Black in to propose its use as a lifting gas, though practical demonstration awaited a gas-tight balloon material. On hearing of the Montgolfier Brothers' invitation, the French Academy member Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (12 November 1746 – 7 April 1823) was a French people, French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due ...

offered a similar demonstration of a hydrogen balloon. Charles and two craftsmen, the Robert brothers, developed a gas-tight material of rubberised silk for the envelope. The hydrogen gas was to be generated by chemical reaction during the filling process.

The Montgolfier designs had several shortcomings, not least the need for dry weather and a tendency for sparks from the fire to set light to the paper balloon. The manned design had a gallery around the base of the balloon rather than the hanging basket of the first, unmanned design, which brought the paper closer to the fire. On their free flight, De Rozier and d'Arlandes took buckets of water and sponges to douse these fires as they arose. On the other hand, the manned design of Charles was essentially modern. As a result of these exploits, the hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carri ...

became known as the ''Montgolfière'' type and the gas balloon the ''Charlière''.

Charles and the Robert brothers' next balloon, '' La Caroline'', was a Charlière that followed Jean Baptiste Meusnier

Jean Baptiste Marie Charles Meusnier de la Place (Tours, 19 June 1754 — le Pont de Cassel, near Mainz, 13 June 1793) was a French mathematician, engineer and Revolutionary general. He is best known for Meusnier's theorem on the curvature o ...

's proposals for an elongated dirigible balloon, and was notable for having an outer envelope with the gas contained in a second, inner ballonet. On 19 September 1784, it completed the first flight of over , between Paris and Beuvry, despite the man-powered propulsive devices proving useless.

In an attempt the next year to provide both endurance and controllability, de Rozier developed a balloon having both hot air and hydrogen gas bags, a design which was soon named after him as the ''Rozière.'' The principle was to use the hydrogen section for constant lift and to navigate vertically by heating and allowing to cool the hot air section, in order to catch the most favourable wind at whatever altitude it was blowing. The balloon envelope was made of goldbeater's skin. The first flight ended in disaster and the approach has seldom been used since.

Cayley and the foundation of modern aeronautics

Sir George Cayley (1773–1857) is widely acknowledged as the founder of modern aeronautics. He was first called the "father of the aeroplane" in 1846 and Henson called him the "father of aerial navigation." He was the first true scientific aerial investigator to publish his work, which included for the first time the underlying principles and forces of flight. In 1809 he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial NavigationPart 1

Part 2

Part 3

''Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy'', 1809–1810. (Via

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

)Raw text

. Retrieved: 30 May 2010. In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air." He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: ''

thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

'', '' lift'', '' drag'' and ''weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is a quantity associated with the gravitational force exerted on the object by other objects in its environment, although there is some variation and debate as to the exact definition.

Some sta ...

'' and distinguished stability and control in his designs.

He developed the modern conventional form of the fixed-wing aeroplane having a stabilising tail with both horizontal and vertical surfaces, flying gliders both unmanned and manned.

He introduced the use of the whirling arm test rig to investigate the aerodynamics of flight, using it to discover the benefits of the curved or cambered aerofoil over the flat wing he had used for his first glider. He also identified and described the importance of dihedral, diagonal bracing and drag reduction, and contributed to the understanding and design of ornithopters and parachute

A parachute is a device designed to slow an object's descent through an atmosphere by creating Drag (physics), drag or aerodynamic Lift (force), lift. It is primarily used to safely support people exiting aircraft at height, but also serves va ...

s.

Another significant invention was the tension-spoked wheel, which he devised in order to create a light, strong wheel for aircraft undercarriage.

The 19th century: Otto Lilienthal and the first human flights

During the 19th century Cayley's ideas were refined, proved and expanded on, culminating in the works of

During the 19th century Cayley's ideas were refined, proved and expanded on, culminating in the works of Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making t ...

.

Lilienthal was a German engineer and businessman who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making the idea of " heavier than air" a reality. Newspapers and magazines published photographs of Lilienthal gliding, favourably influencing public and scientific opinion about the possibility of flying machines becoming practical.

His work led to the development of the modern wing. His flight attempts in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

in the year 1891 are seen as the beginning of human flight and the " Lilienthal Normalsegelapparat" is considered to be the first air plane in series production, making the ''Maschinenfabrik Otto Lilienthal'' in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

the first air plane production company in the world.

Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making t ...

is often referred to as either the "father of aviation" or "father of flight".

Other important investigators included Horatio Phillips.

Branches

Aeronautics may be divided into three main branches,

Aeronautics may be divided into three main branches, Aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' include fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air aircraft such as h ...

, Aeronautical science and Aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

.

Aviation

Aviation is the art or practice of aeronautics. Historically aviation meant only heavier-than-air flight, but nowadays it includes flying in balloons and airships.Aeronautical engineering

Aeronautical engineering covers the design and construction of aircraft, including how they are powered, how they are used and how they are controlled for safe operation., University of Glasgow.

aerodynamics

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

, the science of passing through the air.

With the increasing activity in space flight, nowadays aeronautics and astronautics are often combined as aerospace engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

.

Aerodynamics

The science of aerodynamics deals with the motion of air and the way that it interacts with objects in motion, such as an aircraft. The study of aerodynamics falls broadly into three areas: ''Incompressible flow

In fluid mechanics, or more generally continuum mechanics, incompressible flow is a flow in which the material density does not vary over time. Equivalently, the divergence of an incompressible flow velocity is zero. Under certain conditions, t ...

'' occurs where the air simply moves to avoid objects, typically at subsonic speeds below that of sound (Mach 1).

''Compressible flow

Compressible flow (or gas dynamics) is the branch of fluid mechanics that deals with flows having significant changes in fluid density. While all flows are compressibility, compressible, flows are usually treated as being incompressible flow, incom ...

'' occurs where shock waves appear at points where the air becomes compressed, typically at speeds above Mach 1.

'' Transonic flow'' occurs in the intermediate speed range around Mach 1, where the airflow over an object may be locally subsonic at one point and locally supersonic at another.

Rocketry

Arocket

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

or rocket vehicle is a missile

A missile is an airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight aided usually by a propellant, jet engine or rocket motor.

Historically, 'missile' referred to any projectile that is thrown, shot or propelled towards a target; this ...

, spacecraft, aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

or other vehicle

A vehicle () is a machine designed for self-propulsion, usually to transport people, cargo, or both. The term "vehicle" typically refers to land vehicles such as human-powered land vehicle, human-powered vehicles (e.g. bicycles, tricycles, velo ...

which obtains thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

from a rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

. In all rockets, the exhaust is formed entirely from propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

s carried within the rocket before use. Rocket engines work by action and reaction

As described by the third of Newton's laws of motion of classical mechanics, all forces occur in pairs such that if one object exerts a force on another object, then the second object exerts an equal and opposite reaction force on the first. The t ...

. Rocket engines push rockets forwards simply by throwing their exhaust backwards extremely fast.

Rockets for military and recreational uses date back to at least 13th-century China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. Significant scientific, interplanetary and industrial use did not occur until the 20th century, when rocketry was the enabling technology of the Space Age

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the space race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957, and co ...

, including setting foot on the Moon.

Rockets are used for fireworks

Fireworks are Explosive, low explosive Pyrotechnics, pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large numbe ...

, weaponry, ejection seat

In aircraft, an ejection seat or ejector seat is a system designed to rescue the aircraft pilot, pilot or other aircrew, crew of an aircraft (usually military) in an emergency. In most designs, the seat is propelled out of the aircraft by an exp ...

s, launch vehicle

A launch vehicle is typically a rocket-powered vehicle designed to carry a payload (a crewed spacecraft or satellites) from Earth's surface or lower atmosphere to outer space. The most common form is the ballistic missile-shaped multistage ...

s for artificial satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scienti ...

s, human spaceflight

Human spaceflight (also referred to as manned spaceflight or crewed spaceflight) is spaceflight with a crew or passengers aboard a spacecraft, often with the spacecraft being operated directly by the onboard human crew. Spacecraft can also be ...

and exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

of other planets. While comparatively inefficient for low speed use, they are very lightweight and powerful, capable of generating large accelerations and of attaining extremely high speeds with reasonable efficiency.

Chemical rockets are the most common type of rocket and they typically create their exhaust by the combustion of rocket propellant

Rocket propellant is used as reaction mass ejected from a rocket engine to produce thrust. The energy required can either come from the propellants themselves, as with a chemical rocket, or from an external source, as with ion engines.

Overvi ...

. Chemical rockets store a large amount of energy in an easily released form, and can be very dangerous. However, careful design, testing, construction and use minimizes risks.

See also

References

Citations

Sources

* * * Wilson, E. B. (1920)Aeronautics: A Class Text

', via

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

*

*

External links

Aeronautics

Aviation Terminology

Jeppesen The AVIATION DICTIONARY for pilots and aviation technicians

DTIC ADA032206: Chinese-English Aviation and Space Dictionary

*

Courses

* * * *Research

* * * {{Authority control > Articles containing video clips