Acid–base reaction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The first modern definition of acids and bases in molecular terms was devised by

The first modern definition of acids and bases in molecular terms was devised by

Here, one molecule of water acts as an acid, donating an and forming the conjugate base, , and a second molecule of water acts as a base, accepting the ion and forming the conjugate acid, .

As an example of water acting as an acid, consider an aqueous solution of pyridine, .

In this example, a water molecule is split into a hydrogen cation, which is donated to a pyridine molecule, and a hydroxide ion.

In the Brønsted–Lowry model, the solvent does not necessarily have to be water, as is required by the Arrhenius Acid–Base model. For example, consider what happens when

Here, one molecule of water acts as an acid, donating an and forming the conjugate base, , and a second molecule of water acts as a base, accepting the ion and forming the conjugate acid, .

As an example of water acting as an acid, consider an aqueous solution of pyridine, .

In this example, a water molecule is split into a hydrogen cation, which is donated to a pyridine molecule, and a hydroxide ion.

In the Brønsted–Lowry model, the solvent does not necessarily have to be water, as is required by the Arrhenius Acid–Base model. For example, consider what happens when

Acid–base Physiology

– an on-line text

{{DEFAULTSORT:Acid-Base Reaction Acids Bases (chemistry) Chemical reactions Equilibrium chemistry Inorganic reactions

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, an acid–base reaction is a chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

that occurs between an acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

and a base. It can be used to determine pH via titration

Titration (also known as titrimetry and volumetric analysis) is a common laboratory method of Quantitative research, quantitative Analytical chemistry, chemical analysis to determine the concentration of an identified analyte (a substance to be ...

. Several theoretical frameworks provide alternative conceptions of the reaction mechanisms and their application in solving related problems; these are called the acid–base theories, for example, Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory.

Their importance becomes apparent in analyzing acid–base reactions for gaseous or liquid species, or when acid or base character may be somewhat less apparent. The first of these concepts was provided by the French chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that i ...

, around 1776. – Table of discoveries attributes Antoine Lavoisier as the first to posit a scientific theory in relation to oxyacids.

It is important to think of the acid–base reaction models as theories that complement each other. For example, the current Lewis model has the broadest definition of what an acid and base are, with the Brønsted–Lowry theory being a subset of what acids and bases are, and the Arrhenius theory being the most restrictive.

Acid–base definitions

Historic development

The concept of an acid–base reaction was first proposed in 1754 by Guillaume-François Rouelle, who introduced the word " base" into chemistry to mean a substance which reacts with an acid to give it solid form (as a salt). Bases are mostly bitter in nature.Lavoisier's oxygen theory of acids

The first scientific concept of acids and bases was provided by Lavoisier in around 1776. Since Lavoisier's knowledge of strong acids was mainly restricted to oxoacids, such as (nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

) and (sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

), which tend to contain central atoms in high oxidation states surrounded by oxygen, and since he was not aware of the true composition of the hydrohalic acids ( HF, HCl, HBr, and HI), he defined acids in terms of their containing ''oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

'', which in fact he named from Greek words meaning "acid-former" (). The Lavoisier definition held for over 30 years, until the 1810 article and subsequent lectures by Sir Humphry Davy in which he proved the lack of oxygen in hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

(), hydrogen telluride (), and the hydrohalic acids. However, Davy failed to develop a new theory, concluding that "acidity does not depend upon any particular elementary substance, but upon peculiar arrangement of various substances". One notable modification of oxygen theory was provided by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, who stated that acids are oxides of nonmetals while bases are oxides of metals.

Liebig's hydrogen theory of acids

In 1838, Justus von Liebig proposed that an acid is a hydrogen-containing compound whose hydrogen can be replaced by a metal. This redefinition was based on his extensive work on the chemical composition of organic acids, finishing the doctrinal shift from oxygen-based acids to hydrogen-based acids started by Davy. Liebig's definition, while completely empirical, remained in use for almost 50 years until the adoption of the Arrhenius definition.Arrhenius definition

The first modern definition of acids and bases in molecular terms was devised by

The first modern definition of acids and bases in molecular terms was devised by Svante Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius ( , ; 19 February 1859 – 2 October 1927) was a Swedish scientist. Originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, Arrhenius was one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry. In 1903, he received ...

.Miessler G.L. and Tarr D.A. ''Inorganic Chemistry'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 1999) p. 154 A hydrogen theory of acids, it followed from his 1884 work with Friedrich Wilhelm Ostwald in establishing the presence of ions in aqueous solution and led to Arrhenius receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1903.

As defined by Arrhenius:

* An ''Arrhenius acid'' is a substance that ionises in water to form hydrogen cations (); that is, an acid increases the concentration of H+ ions in an aqueous solution.

This causes the protonation of water, or the creation of the hydronium () ion. Thus, in modern times, the symbol is interpreted as a shorthand for , because it is now known that a bare proton does not exist as a free species in aqueous solution. This is the species which is measured by pH indicator

A pH indicator is a halochromism, halochromic chemical compound added in small amounts to a Solution (chemistry), solution so the pH (acidity or Base (chemistry), basicity) of the solution can be determined visually or spectroscopically by chang ...

s to measure the acidity or basicity of a solution.

* An ''Arrhenius base'' is a substance that dissociates in water to form hydroxide () ions; that is, a base increases the concentration of ions in an aqueous solution.

The Arrhenius definitions of acidity and alkalinity

Alkalinity (from ) is the capacity of water to resist Freshwater acidification, acidification. It should not be confused with base (chemistry), basicity, which is an absolute measurement on the pH scale. Alkalinity is the strength of a buffer s ...

are restricted to aqueous solutions and are not valid for most non-aqueous solutions, and refer to the concentration of the solvent ions. Under this definition, pure and HCl dissolved in toluene are not acidic, and molten NaOH and solutions of calcium amide in liquid ammonia are not alkaline. This led to the development of the Brønsted–Lowry theory and subsequent Lewis theory to account for these non-aqueous exceptions.

The reaction of an acid with a base is called a neutralization reaction. The products of this reaction are a salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

and water.

In this traditional representation an acid–base neutralization reaction is formulated as a double-replacement reaction. For example, the reaction of hydrochloric acid (HCl) with sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

(NaOH) solutions produces a solution of sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

(NaCl) and some additional water molecules.

The modifier ( aq) in this equation was implied by Arrhenius, rather than included explicitly. It indicates that the substances are dissolved in water. Though all three substances, HCl, NaOH and NaCl are capable of existing as pure compounds, in aqueous solutions they are fully dissociated into the aquated ions and .

Example: Baking powder

Baking powder is used to cause the dough for breads and cakes to "rise" by creating millions of tinycarbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

bubbles. Baking powder is not to be confused with baking soda, which is sodium bicarbonate (). Baking powder is a mixture of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) and acidic salts. The bubbles are created because, when the baking powder is combined with water, the sodium bicarbonate and acid salts react to produce gaseous carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

.

Whether commercially or domestically prepared, the principles behind baking powder formulations remain the same. The acid–base reaction can be generically represented as shown:

The real reactions are more complicated because the acids are complicated. For example, starting with sodium bicarbonate and monocalcium phosphate (), the reaction produces carbon dioxide by the following stoichiometry

Stoichiometry () is the relationships between the masses of reactants and Product (chemistry), products before, during, and following chemical reactions.

Stoichiometry is based on the law of conservation of mass; the total mass of reactants must ...

:John Brodie, John Godber "Bakery Processes, Chemical Leavening Agents" in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology 2001, John Wiley & Sons.

A typical formulation (by weight) could call for 30% sodium bicarbonate, 5–12% monocalcium phosphate, and 21–26% sodium aluminium sulfate. Alternately, a commercial baking powder might use sodium acid pyrophosphate as one of the two acidic components instead of sodium aluminium sulfate. Another typical acid in such formulations is cream of tartar (), a derivative of tartaric acid.

Brønsted–Lowry definition

The Brønsted–Lowry definition, formulated in 1923, independently by Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted in Denmark and Martin Lowry in England, is based upon the idea of protonation of bases through the deprotonation of acids – that is, the ability of acids to "donate" hydrogen cations () otherwise known asprotons

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' ( elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an electron (the pro ...

to bases, which "accept" them. – According to this page, the original definition was that "acids have a tendency to lose a proton""Removal and addition of a proton from the nucleus of an atom does not occur it would require very much more energy than is involved in the dissociation of acids."

An acid–base reaction is, thus, the removal of a proton from the acid and its addition to the base. The removal of a proton from an acid produces its '' conjugate base'', which is the acid with a proton removed. The reception of a proton by a base produces its '' conjugate acid'', which is the base with a proton added.

Unlike the previous definitions, the Brønsted–Lowry definition does not refer to the formation of salt and solvent, but instead to the formation of ''conjugate acids'' and ''conjugate bases'', produced by the transfer of a proton from the acid to the base. In this approach, acids and bases are fundamentally different in behavior from salts, which are seen as electrolytes, subject to the theories of Debye, Onsager, and others. An acid and a base react not to produce a salt and a solvent, but to form a new acid and a new base. The concept of neutralization is thus absent. Brønsted–Lowry acid–base behavior is formally independent of any solvent, making it more all-encompassing than the Arrhenius model. The calculation of pH under the Arrhenius model depended on alkalis (bases) dissolving in water ( aqueous solution). The Brønsted–Lowry model expanded what could be pH tested using insoluble and soluble solutions (gas, liquid, solid).

The general formula for acid–base reactions according to the Brønsted–Lowry definition is:

where HA represents the acid, B represents the base, represents the conjugate acid of B, and represents the conjugate base of HA.

For example, a Brønsted–Lowry model for the dissociation of hydrochloric acid (HCl) in aqueous solution would be the following:

The removal of from the produces the chloride ion, , the conjugate base of the acid. The addition of to the (acting as a base) forms the hydronium ion, , the conjugate acid of the base.

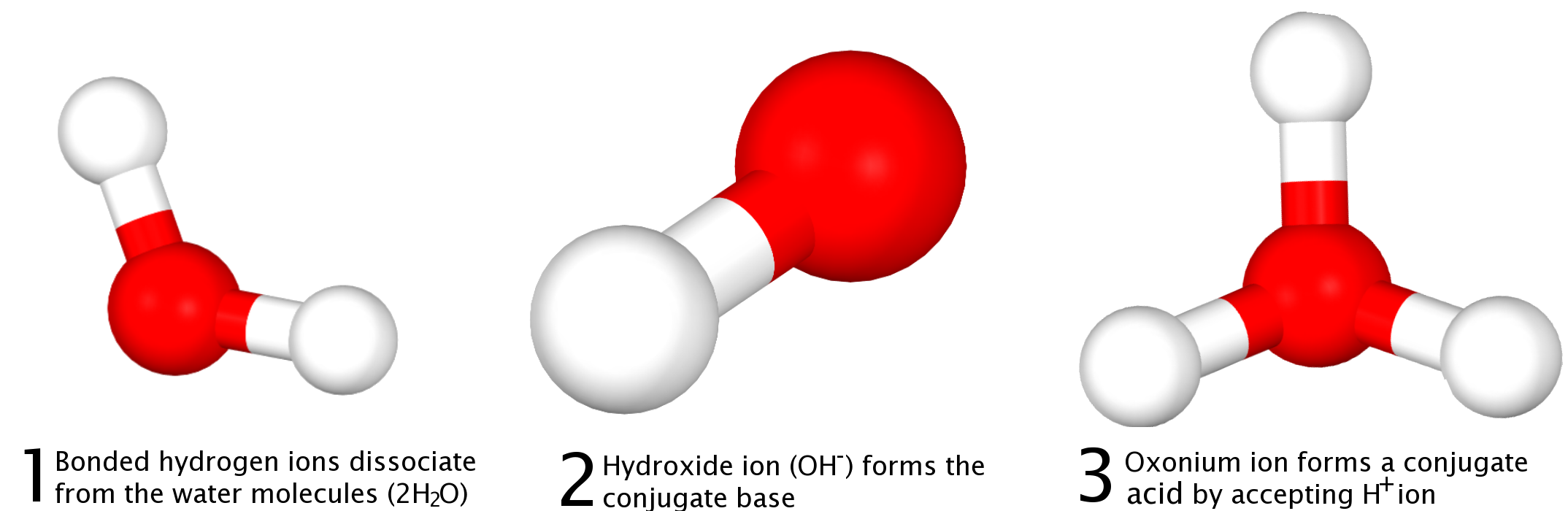

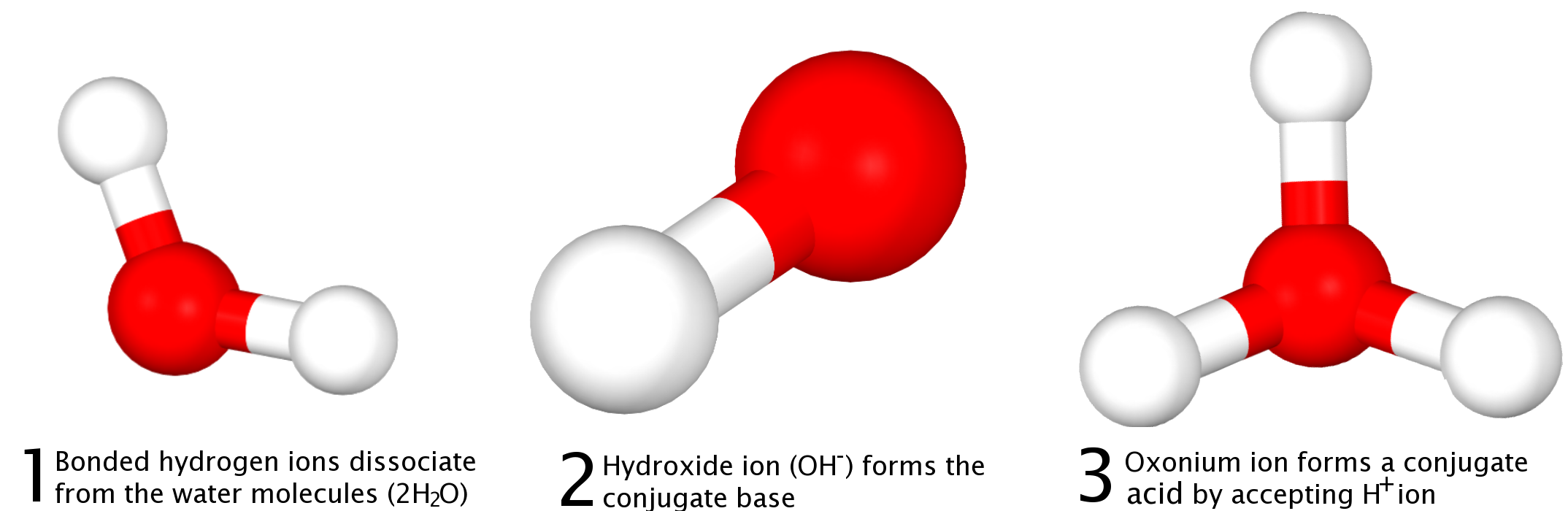

Water is amphoteric that is, it can act as both an acid and a base. The Brønsted–Lowry model explains this, showing the dissociation of water into low concentrations of hydronium and hydroxide ions:

This equation is demonstrated in the image below:

Here, one molecule of water acts as an acid, donating an and forming the conjugate base, , and a second molecule of water acts as a base, accepting the ion and forming the conjugate acid, .

As an example of water acting as an acid, consider an aqueous solution of pyridine, .

In this example, a water molecule is split into a hydrogen cation, which is donated to a pyridine molecule, and a hydroxide ion.

In the Brønsted–Lowry model, the solvent does not necessarily have to be water, as is required by the Arrhenius Acid–Base model. For example, consider what happens when

Here, one molecule of water acts as an acid, donating an and forming the conjugate base, , and a second molecule of water acts as a base, accepting the ion and forming the conjugate acid, .

As an example of water acting as an acid, consider an aqueous solution of pyridine, .

In this example, a water molecule is split into a hydrogen cation, which is donated to a pyridine molecule, and a hydroxide ion.

In the Brønsted–Lowry model, the solvent does not necessarily have to be water, as is required by the Arrhenius Acid–Base model. For example, consider what happens when acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main compone ...

, , dissolves in liquid ammonia.

An ion is removed from acetic acid, forming its conjugate base, the acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic, or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

ion, . The addition of an ion to an ammonia molecule of the solvent creates its conjugate acid, the ammonium ion, .

The Brønsted–Lowry model calls hydrogen-containing substances (like ) acids. Thus, some substances, which many chemists considered to be acids, such as or , are excluded from this classification due to lack of hydrogen. Gilbert N. Lewis wrote in 1938, "To restrict the group of acids to those substances that contain hydrogen interferes as seriously with the systematic understanding of chemistry as would the restriction of the term oxidizing agent to substances containing oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

." Furthermore, and are not considered Brønsted bases, but rather salts containing the bases and .

Lewis definition

The hydrogen requirement of Arrhenius and Brønsted–Lowry was removed by the Lewis definition of acid–base reactions, devised by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1923, – Table of discoveries attributes the date of publication/release for the Lewis theory as 1924. in the same year as Brønsted–Lowry, but it was not elaborated by him until 1938. Instead of defining acid–base reactions in terms of protons or other bonded substances, the Lewis definition defines a base (referred to as a ''Lewis base'') to be a compound that can donate an '' electron pair'', and an acid (a ''Lewis acid'') to be a compound that can receive this electron pair. For example, boron trifluoride, is a typical Lewis acid. It can accept a pair of electrons as it has a vacancy in its octet. Thefluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an Inorganic chemistry, inorganic, Monatomic ion, monatomic Ion#Anions and cations, anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose ...

ion has a full octet and can donate a pair of electrons. Thus

is a typical Lewis acid, Lewis base reaction. All compounds of group 13 elements with a formula can behave as Lewis acids. Similarly, compounds of group 15 elements with a formula , such as amines, , and phosphine

Phosphine (IUPAC name: phosphane) is a colorless, flammable, highly toxic compound with the chemical formula , classed as a pnictogen hydride. Pure phosphine is odorless, but technical grade samples have a highly unpleasant odor like rotting ...

s, , can behave as Lewis bases. Adducts between them have the formula with a dative covalent bond, shown symbolically as ←, between the atoms A (acceptor) and D (donor). Compounds of group 16

The chalcogens (ore forming) ( ) are the chemical elements in group 16 of the periodic table. This group is also known as the oxygen family. Group 16 consists of the elements oxygen (O), sulfur (S), selenium (Se), tellurium (Te), and the ...

with a formula may also act as Lewis bases; in this way, a compound like an ether, , or a thioether, , can act as a Lewis base. The Lewis definition is not limited to these examples. For instance, carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

acts as a Lewis base when it forms an adduct with boron trifluoride, of formula .

Adducts involving metal ions are referred to as co-ordination compounds; each ligand donates a pair of electrons to the metal ion. The reaction

can be seen as an acid–base reaction in which a stronger base (ammonia) replaces a weaker one (water).

The Lewis and Brønsted–Lowry definitions are consistent with each other since the reaction

is an acid–base reaction in both theories.

Solvent system definition

One of the limitations of the Arrhenius definition is its reliance on water solutions. Edward Curtis Franklin studied the acid–base reactions in liquid ammonia in 1905 and pointed out the similarities to the water-based Arrhenius theory. Albert F.O. Germann, working with liquid phosgene, , formulated the solvent-based theory in 1925, thereby generalizing the Arrhenius definition to cover aprotic solvents. Germann pointed out that in many solutions, there are ions in equilibrium with the neutral solvent molecules: * solvonium ions: a generic name for positive ions. These are also sometimes called solvo-acids; when protonated solvent, they are lyonium ions. * solvate ions: a generic name for negative ions. These are also sometimes called solve-bases; when deprotonated solvent, they are lyate ions. For example, water andammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

undergo such dissociation into hydronium and hydroxide, and ammonium

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) polyatomic ion, molecular ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation, addition of a proton (a hydrogen nucleu ...

and amide, respectively:

Some aprotic systems also undergo such dissociation, such as dinitrogen tetroxide into nitrosonium and nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

, antimony trichloride into dichloroantimonium and tetrachloroantimonate, and phosgene into chlorocarboxonium and chloride:

A solute that causes an increase in the concentration of the solvonium ions and a decrease in the concentration of solvate ions is defined as an ''acid''. A solute that causes an increase in the concentration of the solvate ions and a decrease in the concentration of the solvonium ions is defined as a ''base''.

Thus, in liquid ammonia, (supplying ) is a strong base, and (supplying ) is a strong acid. In liquid sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless gas with a pungent smell that is responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is r ...

(), thionyl compounds (supplying ) behave as acids, and sulfites (supplying ) behave as bases.

The non-aqueous acid–base reactions in liquid ammonia are similar to the reactions in water:

Nitric acid can be a base in liquid sulfuric acid:

The unique strength of this definition shows in describing the reactions in aprotic solvents; for example, in liquid :

Because the solvent system definition depends on the solute as well as on the solvent itself, a particular solute can be either an acid or a base depending on the choice of the solvent: is a strong acid in water, a weak acid in acetic acid, and a weak base in fluorosulfonic acid; this characteristic of the theory has been seen as both a strength and a weakness, because some substances (such as and ) have been seen to be acidic or basic on their own right. On the other hand, solvent system theory has been criticized as being too general to be useful. Also, it has been thought that there is something intrinsically acidic about hydrogen compounds, a property not shared by non-hydrogenic solvonium salts.

Lux–Flood definition

This acid–base theory was a revival of the oxygen theory of acids and bases proposed by German chemist Hermann Lux in 1939, further improved by Håkon Flood and is still used in moderngeochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the e ...

and electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between Electric potential, electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve Electron, electrons moving via an electronic ...

of molten salts. This definition describes an acid as an oxide ion () acceptor and a base as an oxide ion donor. For example:

This theory is also useful in the systematisation of the reactions of noble gas compounds, especially the xenon oxides, fluorides, and oxofluorides.

Usanovich definition

Mikhail Usanovich developed a general theory that does not restrict acidity to hydrogen-containing compounds, but his approach, published in 1938, was even more general than Lewis theory. Usanovich's theory can be summarized as defining an acid as anything that accepts negative species or donates positive ones, and a base as the reverse. This defined the concept ofredox

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is t ...

(oxidation-reduction) as a special case of acid–base reactions.

Some examples of Usanovich acid–base reactions include:

Rationalizing the strength of Lewis acid–base interactions

HSAB theory

In 1963, Ralph Pearson proposed a qualitative concept known as the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases principle. later made quantitative with help of Robert Parr in 1984. 'Hard' applies to species that are small, have high charge states, and are weakly polarizable. 'Soft' applies to species that are large, have low charge states and are strongly polarizable. Acids and bases interact, and the most stable interactions are hard–hard and soft–soft. This theory has found use in organic and inorganic chemistry.ECW model

The ECW model created by Russell S. Drago is a quantitative model that describes and predicts the strength of Lewis acid base interactions, . The model assigned and parameters to many Lewis acids and bases. Each acid is characterized by an and a . Each base is likewise characterized by its own and . The and parameters refer, respectively, to the electrostatic and covalent contributions to the strength of the bonds that the acid and base will form. The equation is The term represents a constant energy contribution for acid–base reaction such as the cleavage of a dimeric acid or base. The equation predicts reversal of acids and base strengths. The graphical presentations of the equation show that there is no single order of Lewis base strengths or Lewis acid strengths.Acid–base equilibrium

The reaction of a strong acid with a strong base is essentially a quantitative reaction. For example, In this reaction both the sodium and chloride ions are spectators as the neutralization reaction, does not involve them. With weak bases addition of acid is not quantitative because a solution of a weak base is a buffer solution. A solution of a weak acid is also a buffer solution. When a weak acid reacts with a weak base an equilibrium mixture is produced. For example, adenine, written as AH, can react with a hydrogenphosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

ion, .

The equilibrium constant for this reaction can be derived from the acid dissociation constants of adenine and of the dihydrogen phosphate ion.

The notation signifies "concentration of X". When these two equations are combined by eliminating the hydrogen ion concentration, an expression for the equilibrium constant, is obtained.

Acid–alkali reaction

An acid–alkali reaction is a special case of an acid–base reaction, where the base used is also an alkali. When an acid reacts with an alkali salt (a metal hydroxide), the product is a metalsalt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

and water. Acid–alkali reactions are also neutralization reactions.

In general, acid–alkali reactions can be simplified to

:

by omitting spectator ions.

Acids are in general pure substances that contain hydrogen cations () or cause them to be produced in solutions. Hydrochloric acid () and sulfuric acid () are common examples. In water, these break apart into ions:

:

The alkali breaks apart in water, yielding dissolved hydroxide ions:

:.

See also

* Acid–base titration * Deprotonation * Donor number * Electron configuration * Gutmann–Beckett method * Lewis structure * Nucleophilic substitution * Neutralization (chemistry) * Protonation *Redox

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is t ...

reactions

* Resonance (chemistry)

In chemistry, resonance, also called mesomerism, is a way of describing Chemical bond, bonding in certain molecules or polyatomic ions by the combination of several contributing structures (or ''forms'', also variously known as ''resonance struc ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * *External links

Acid–base Physiology

– an on-line text

{{DEFAULTSORT:Acid-Base Reaction Acids Bases (chemistry) Chemical reactions Equilibrium chemistry Inorganic reactions