|

Siderophore

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity iron- chelating compounds that are secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. They help the organism accumulate iron. Although a widening range of siderophore functions is now being appreciated, siderophores are among the strongest (highest affinity) Fe3+ binding agents known. Phytosiderophores are siderophores produced by plants. Scarcity of soluble iron Despite being one of the most abundant elements in the Earth's crust, iron is not readily bioavailable. In most aerobic environments, such as the soil or sea, iron exists in the ferric (Fe3+) state, which tends to form insoluble rust-like solids. To be effective, nutrients must not only be available, they must be soluble. Microbes release siderophores to scavenge iron from these mineral phases by formation of soluble Fe3+ complexes that can be taken up by active transport mechanisms. Many siderophores are nonribosomal peptides, although several are biosynthe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Siderocalin

Siderocalin (Scn), lipocalin-2, NGAL, 24p3 is a mammalian lipocalin-type protein that can prevent iron acquisition by pathogenic bacteria by binding siderophores, which are iron-binding chelators made by microorganisms. Iron serves as a key nutrient in host (biology), host-pathogen interactions, and pathogens can acquire iron from the host organism via Biosynthesis, synthesis and release siderophores such as enterobactin. Siderocalin is a part of the mammalian defence mechanism and acts as an antibacterial agent. Crystallographic studies of Scn demonstrated that it includes a wikt:calyx, calyx, a ligand-binding domain that is lined with polar cationic groups. Central to the siderophore/siderocalin recognition mechanism are hybrid electrostatic/cation-pi interactions. To evade the host defences, pathogens evolved to produce structurally varied siderophores that would not be recognized by siderocalin, allowing the bacteria to acquire iron. Iron requirements of host organisms ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Petrobactin

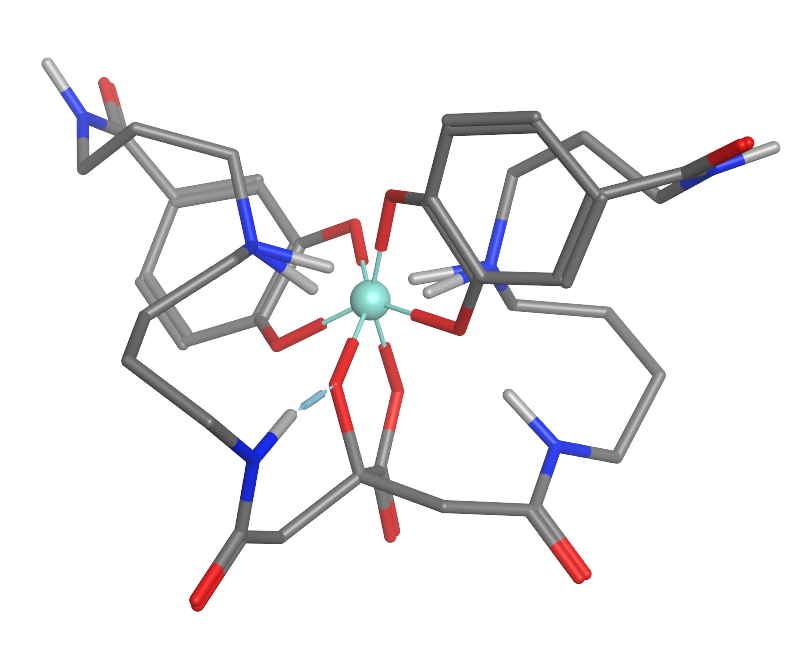

Petrobactin is a bis-catechol siderophore found in Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus, M. hydrocarbonoclasticus, Alteromonas macleodii, A. macleodii, and the anthrax-producing Bacillus anthracis, B. anthracis. Like other siderophores petrobactin is a highly specific iron(III) transport ligand, contributing to the Siderophore#Marine water, marine microbial uptake of environmental iron. The iron-Chelation, chelated petrobactin complex readily undergoes a Photodissociation, photolytic oxidative decarboxylation due to its α-hydroxy carboxylate group, converting iron(III) to the more biologically useful iron(II). Biological function Like other siderophores, petrobactin is secreted by an animal pathogenic bacterium. B. anthracis uses petrobactin to acquire iron from its host. Interestingly, while the 3,4-catecholate ends of petrobactin do not improve iron(III) affinity relative to hydroxamate ends, they speed up iron removal from human diferric transferrin. Petrobactin in its fe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacillus Anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent (obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a type of zoonosis, as it is transmitted from animals to humans. It was discovered by a German physician Robert Koch in 1876, and became the first bacterium to be experimentally shown as a pathogen. The discovery was also the first scientific evidence for the germ theory of diseases. ''B. anthracis'' measures about 3 to 5 μm long and 1 to 1.2 μm wide. The reference genome consists of a 5,227,419 bp circular chromosome and two extrachromosomal DNA plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2, of 181,677 and 94,830 bp respectively, which are responsible for the pathogenicity. It forms a protective layer called endospore by which it can remain inactive for many years and suddenly becomes infective under suitable environmental conditions. Because of the resilience ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Deferoxamine

Deferoxamine (DFOA), also known as desferrioxamine and sold under the brand name Desferal, is a medication that binds iron and aluminium. It is specifically used in iron overdose, hemochromatosis either due to multiple blood transfusions or an underlying genetic condition, and aluminium toxicity in people on dialysis. It is used by injection into a muscle, vein, or under the skin. Common side effects include pain at the site of injection, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, hearing loss, and eye problems. Severe allergic reactions including anaphylaxis and low blood pressure may occur. It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe for the baby. Deferoxamine is a siderophore from the bacteria '' Streptomyces pilosus''. Deferoxamine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1968. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. Medical uses Deferoxamine is used to treat acute iron poisoning, especially in small children. This agent i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most abundant element in the Earth's crust, being mainly deposited by meteorites in its metallic state. Extracting usable metal from iron ores requires kilns or furnaces capable of reaching , about 500 °C (900 °F) higher than that required to smelt copper. Humans started to master that process in Eurasia during the 2nd millennium BC and the use of iron tools and weapons began to displace copper alloys – in some regions, only around 1200 BC. That event is considered the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. In the modern world, iron alloys, such as steel, stainless steel, cast iron and special steels, are by far the most common industrial metals, due to their mechan ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ferric

In chemistry, iron(III) or ''ferric'' refers to the chemical element, element iron in its +3 oxidation number, oxidation state. ''Ferric chloride'' is an alternative name for iron(III) chloride (). The adjective ''ferrous'' is used instead for iron(II) salts, containing the cation Fe2+. The word ''wikt:ferric, ferric'' is derived from the Latin word , meaning "iron". Although often abbreviated as Fe3+, that naked ion does not exist except under extreme conditions. Iron(III) centres are found in many compounds and coordination complexes, where Fe(III) is bonded to several Ligand, ligands. A molecular ferric complex is the anion ferrioxalate, , with three bidentate oxalate ions surrounding the Fe core. Relative to lower oxidation states, ferric is less common in organoiron chemistry, but the ferrocenium cation is well known. Iron(III) in biology All known forms of life require iron, which usually exists in Fe(II) or Fe(III) oxidation states. Many proteins in living beings cont ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Enterobactin

Enterobactin (also known as enterochelin) is a high affinity siderophore that acquires iron for microbial systems. It is primarily found in Gram-negative bacteria, such as ''Escherichia coli'' and ''Salmonella typhimurium''. Enterobactin is the strongest siderophore known, binding to the ferric ion (Fe3+) with affinity K = 1052 M−1. This value is substantially larger than even some synthetic metal chelators, such as EDTA (Kf,Fe3+ ~ 1025 M−1). Due to its high affinity, enterobactin is capable of chelating even in environments where the concentration of ferric ion is held very low, such as within living organisms. Pathogenic bacteria can steal iron from other living organisms using this mechanism, even though the concentration of iron is kept extremely low due to the toxicity of free iron. Structure and biosynthesis Chorismic acid, an aromatic amino acid precursor, is converted to 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) by a series of enzymes, EntA, EntB and EntC. An amide linkage of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin (LF), also known as lactotransferrin (LTF), is a multifunctional protein of the transferrin family. Lactoferrin is a globular proteins, globular glycoprotein with a molecular mass of about 80 Atomic mass unit, kDa that is widely represented in various secretory fluids, such as milk, saliva, tears, and Mucus, nasal secretions. Lactoferrin is also present in secondary granules of Granulocyte, PMNs and is secreted by some Centroacinar cells, acinar cells. Lactoferrin can be purified from milk or produced Recombinant DNA, recombinantly. Human colostrum (''"first milk"'') has the highest concentration, followed by human milk, then cow milk (150 mg/L). Lactoferrin is one of the components of the immune system of the body; it has antimicrobial activity (bacteriocide, fungicide) and is part of the innate defense, mainly at mucoses. It is constantly produced and released into saliva, tears, as well as seminal and vaginal fluid. Lactoferrin provides Antiseptic, antibacteria ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacillibactin

Bacillibactin is a catechol-based siderophore secreted by members of the genus ''Bacillus'', including ''Bacillus anthracis'' and ''Bacillus subtilis''. It is involved in the chelation of ferric iron (Fe3+) from the surrounding environment and is subsequently transferred into the bacterial cytoplasm via the use of ABC transporters. Biosynthesis The biosynthetic pathway of bacillibactin was first identified by May et al. in the Gram-positive '' B. subtilis''. The siderophore is synthesized through multimodular non ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), similar to enterobactin. However, unlike enterobactin, the genes responsible for encoding the bacillibactin synthetases are all located in one operon. This gene cluster is termed ''dhb'' – cognate to the catecholic structure of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate (DHB) – and it can be divided into the specific genes responsible for encoding the enzymes. The three genes are ''dhbE, dhbB,'' and ''dhbF'', which get translated into DhbE, DhbB, a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chelation

Chelation () is a type of bonding of ions and their molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom. These ligands are called chelants, chelators, chelating agents, or sequestering agents. They are usually organic compounds, but this is not a necessity. The word ''chelation'' is derived from Greek χηλή, ''chēlē'', meaning "claw"; the ligands lie around the central atom like the claws of a crab. The term ''chelate'' () was first applied in 1920 by Sir Gilbert T. Morgan and H. D. K. Drew, who stated: "The adjective chelate, derived from the great claw or ''chele'' (Greek) of the crab or other crustaceans, is suggested for the caliperlike groups which function as two associating units and fasten to the central atom so as to produce heterocyclic rings." Chelation is useful in applications such as providing nutritional supplements, in chel ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nonribosomal Peptide

Nonribosomal peptides (NRP) are a class of peptide secondary metabolites, usually produced by microorganisms like bacterium, bacteria and fungi. Nonribosomal peptides are also found in higher organisms, such as nudibranchs, but are thought to be made by bacteria commensalism, inside these organisms. While there exist a wide range of peptides that are not synthesized by ribosomes, the term ''nonribosomal peptide'' typically refers to a very specific set of these as discussed in this article. Nonribosomal peptides are synthesized by nonribosomal peptide synthetases, which, unlike the ribosomes, are independent of messenger RNA. Each nonribosomal peptide synthetase can synthesize only one type of peptide. Nonribosomal peptides often have cyclic compound, cyclic and/or branched structures, can contain non-proteinogenic amino acids including D-amino acids, carry modifications like ''Nitrogen, N''-methyl and ''N''-formyl groups, or are Glycosylation, glycosylated, Acylation, acylated, Ha ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |