|

ŪāKung People

The ŪāKung ( ) are one of the San peoples who live mostly on the western edge of the Kalahari Desert, Kalahari desert, Ovamboland (northern Namibia and southern Angola), and Botswana. The names ''ŪāKung'' (''ŪāXun'') and ''Ju'' are variant words for 'people', preferred by different ŪāKung groups. This band society, band level society used traditional methods of hunting and gathering for subsistence up until the 1970s. Today, the great majority of ŪāKung people live in the villages of Bantu pastoralists and European ranchers. Beliefs The ŪāKung people of Southern Africa recognize a Creator deity, Supreme Being, ŪāXu, who is the Creator and Upholder of life. Like other African High Gods, he also punishes man by means of the weather, and the Otjimpolo-ŪāKung know him as Erob, who "knows everything". They also have Animism, animistic and Animatism, animatistic beliefs, which means they believe in both personifications and impersonal forces. Amongst the ŪāKung there is a strong ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Marjorie Shostak

Marjorie Shostak (May 11, 1945 ŌĆō October 6, 1996) was an American anthropologist. Though she never received a formal degree in anthropology, she conducted extensive fieldwork among the !Kung San people of the Kalahari Desert in south-western Africa and was widely known for her descriptions of the lives of women in this hunter-gatherer society. Life Shostak was raised in Brooklyn, New York. She received her B.A. in literature from Brooklyn College, where she was a supporter of the women's equal rights movement, and met her future husband, Melvin Konner. From 1969 to 1971, Shostak and Konner lived among the !Kung San in the Dobe region of southwest Africa, on the border between Botswana and South Africa. There they learned the !Kung language and conducted anthropological fieldwork. While her husband looked at medical issues like nutrition and fertility, Shostak examined the role of women in the !Kung San society, becoming close with one woman in particular, known by the pseudon ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Kx╩╝a Languages

The Kx╩╝a ( ) languages, also called JuŌĆōŪéHoan ( ), is a language family established in 2010 linking the Ūé╩╝Amkoe (ŪéHoan) language with the ŪāKung (Juu) dialect cluster, a relationship that had been suspected for a decade. Along with the Tuu languages and Khoe languages, they are one of three language families indigenous to southern Africa, which are typologically similar due to areal effects. Languages * Ūé╩╝Amkoe ( moribund) * ŪāKung (also ''ŪāXun'' or ''Ju,'' formerly ''Northern Khoisan''; a dialect cluster) Ūé╩╝Amkoe had previously been lumped in with the Tuu languages, perhaps over confusion with the dialect name ŪéH╚Ź╚ün, but the only thing they have in common are typological features such as their bilabial click The bilabial clicks are a family of click consonants that sound like a smack of the lips. They are found as phonemes only in the small Tuu language family (currently two languages, one down to its last speaker), in the ŪéŌĆÖAmkoe language ...s. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Richard Borshay Lee

Richard Borshay Lee (born 1937) is a Canadian anthropologist. Lee has studied at the University of Toronto and University of California, Berkeley, where he received a Ph.D. He holds a position at the University of Toronto as Professor Emeritus of Anthropology. Lee researches issues concerning the indigenous people of Botswana and Namibia, particularly their ecology and history. Known best for his work on the Ju'/hoansi, Lee won the 1980 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for his book ''The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society''. With Irven DeVore, Lee was co-organiser of the 1966 University of Chicago Symposium on "Man the Hunter". Lee co-edited with Richard Daly ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunter-Gatherers'', which was first published in 1999. In 2003, ''Anthropologica'', the journal of the Canadian Anthropology Society, dedicated an issue to Lee's oeuvre. In 2011 he co-authored the children's book ''Africans Thought of It: Amazing Innovations'' with Bathseba O ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Theory Of Regal And Kungic Societal Structures

The theory of regal and kungic societal structures, or regality theory, is a theory that seeks to explain certain cultural differences based on perceived collective danger and fear. People will show a psychological preference for a strong leader and strict discipline if they live in a society full of conflict and danger, while people in a peaceful and safe environment will prefer an egalitarian and tolerant culture, according to this theory. The psychological preferences of the individual members of a social group is reflected in the social structure and culture of the whole group. A dangerous and conflict-filled environment will drive the culture in the direction of strict hierarchy and authoritarianism. This type of culture is called ''regal''. The opposite situation is seen in a safe and peaceful environment, where the culture is developing in the direction of egalitarianism and tolerance. This type of culture is called ''kungic''. Most cultures and societies are found somewh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Bridewealth

Bride price, bride-dowry, bride-wealth, bride service or bride token, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the woman or the family of the woman he will be married to or is just about to marry. Bride dowry is equivalent to dowry paid to the groom in some cultures, or used by the bride to help establish the new household, and dower, which is property settled on the bride herself by the groom at the time of marriage. Some cultures may practice both simultaneously. Many cultures practiced bride dowry prior to existing records. The tradition of giving bride dowry is practiced in many East Asian countries, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, parts of Africa and in some Pacific Island societies, notably those in Melanesia. The amount changing hands may range from a token to continue the traditional ritual, to many thousands of US dollars in some marriages in Thailand, and as much as $100,000 in exceptionally large bride dowry in parts of Papua New G ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Adansonia

''Adansonia'' is a genus of medium-to-large deciduous trees known as baobabs ( or ). The eight species of ''Adansonia'' are native to Africa, Australia, and Madagascar but have also been introduced to other regions of the world, including Barbados, where several of the baobabs there are suspected to have originated from Africa. Other baobabs have been introduced to Asia. A genomic and ecological analysis further suggests that the genus itself originated from Madagascar. The generic name ''Adansonia'' honours Michel Adanson, the French naturalist and explorer who provided the first detailed botanical description and illustrations of ''Adansonia digitata''. The baobab, however, is also known as the "upside down tree," a name attributable to the trees' overall appearance and historical myths. Baobabs are among the most long-lived of vascular plants and have large flowers that are reproductive for a maximum of 15 hours. The flowers open around dusk with sufficiently rapid moveme ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of resources being spent on weak or disabled offspring. Unwanted infants were usually abandoned to die of exposure, but in some societies they were deliberately killed. Infanticide is generally illegal, but in some places the practice is tolerated, or the prohibition is not strictly enforced. Most Stone Age human societies routinely practiced infanticide, and estimates of children killed by infanticide in the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras vary from 15 to 50 percent. Infanticide continued to be common in most societies after the historical era began, including ancient Greece, Roman Empire, ancient Rome, the Phoenicians, ancient China, ancient Japan, Pre-Islamic Arabia, early modern Europe, Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal Australia, Indigenous ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

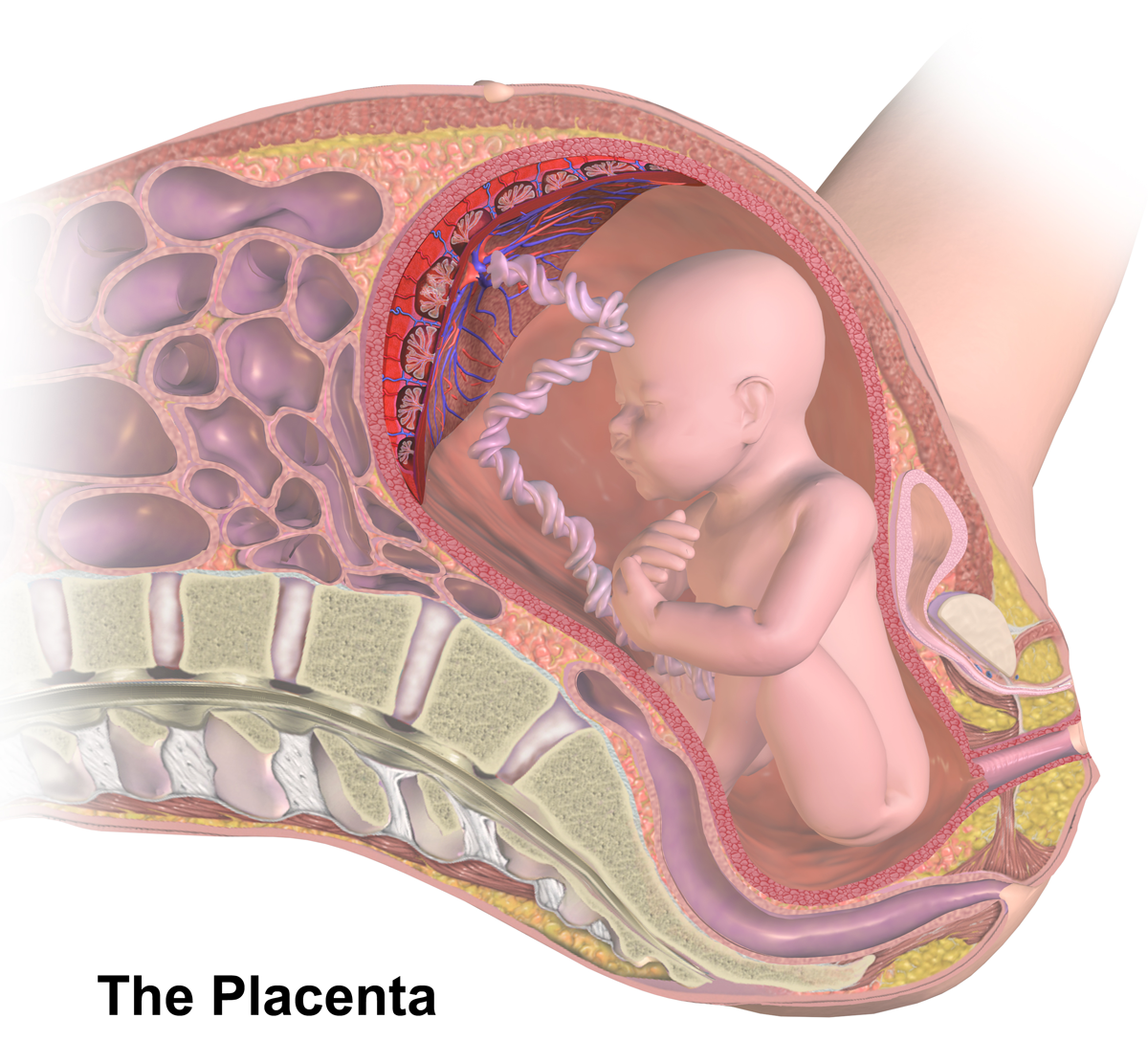

Placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between the physically separate maternal and fetal circulations, and is an important endocrine organ, producing hormones that regulate both maternal and fetal physiology during pregnancy. The placenta connects to the fetus via the umbilical cord, and on the opposite aspect to the maternal uterus in a species-dependent manner. In humans, a thin layer of maternal decidual ( endometrial) tissue comes away with the placenta when it is expelled from the uterus following birth (sometimes incorrectly referred to as the 'maternal part' of the placenta). Placentas are a defining characteristic of placental mammals, but are also found in marsupials and some non-mammals with varying levels of development. Mammalian placentas probably first evolved abou ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Lotus Birth

Lotus birth (or umbilical cord nonseverance - UCNS) is the practice of leaving the umbilical cord uncut after childbirth so that the baby is left attached to the placenta until the cord naturally separates at the umbilicus. This usually occurs within 3ŌĆō10 days after birth. The practice is performed mainly for spiritual purposes, including for the perceived spiritual connection between the placenta and the newborn. As of December 2008, no evidence exists to support any medical benefits for the baby. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has warned about the risks of infection as the decomposing placenta tissue becomes a nest for infectious bacteria such as Staphylococcus. In one such case a 20-hour old baby whose parents chose UCNS was brought to the hospital in an agonal state, was diagnosed with sepsis and required an antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks. History Although recently arisen as an alternative birth phenomenon in the West, super-delayed (1+ hours ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |

Umbilical Cord

In Placentalia, placental mammals, the umbilical cord (also called the navel string, birth cord or ''funiculus umbilicalis'') is a conduit between the developing embryo or fetus and the placenta. During prenatal development, the umbilical cord is physiologically and genetically part of the fetus and (in humans) normally contains two arteries (the umbilical arteries) and one vein (the umbilical vein), buried within Wharton's jelly. The umbilical vein supplies the fetus with oxygenated, nutrient-rich blood from the placenta. Conversely, the fetal heart pumps low-oxygen, nutrient-depleted blood through the umbilical arteries back to the placenta. Structure and development The umbilical cord develops from and contains remnants of the yolk sac and allantois. It forms by the fifth week of human embryogenesis, development, replacing the yolk sac as the source of nutrients for the embryo. The cord is not directly connected to the mother's circulatory system, but instead joins the pla ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] [Amazon] |