suanpan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The suanpan (), also spelled suan pan or souanpan) is an

The suanpan (), also spelled suan pan or souanpan) is an

The word "abacus" was first mentioned by Xu Yue (160–220) in his book ''suanshu jiyi'' (算数记遗), or ''Notes on Traditions of Arithmetic Methods'', in the

The word "abacus" was first mentioned by Xu Yue (160–220) in his book ''suanshu jiyi'' (算数记遗), or ''Notes on Traditions of Arithmetic Methods'', in the

The most mysterious and seemingly superfluous fifth lower bead, likely inherited from counting rods as suggested by the image above, was used to simplify and speed up addition and subtraction somewhat, as well as to decrease the chances of error. Its use was demonstrated, for example, in the first book devoted entirely to suanpan: ''Computational Methods with the Beads in a Tray'' (''Pánzhū Suànfǎ'' 盤珠算法) by Xú Xīnlǔ 徐心魯 (1573, Late Ming dynasty).

A simplify explanation on how to use the 5th beads is show

The most mysterious and seemingly superfluous fifth lower bead, likely inherited from counting rods as suggested by the image above, was used to simplify and speed up addition and subtraction somewhat, as well as to decrease the chances of error. Its use was demonstrated, for example, in the first book devoted entirely to suanpan: ''Computational Methods with the Beads in a Tray'' (''Pánzhū Suànfǎ'' 盤珠算法) by Xú Xīnlǔ 徐心魯 (1573, Late Ming dynasty).

A simplify explanation on how to use the 5th beads is show

here

The following two animations show the details of this particular usage:

File:Panzhu Suanfa addition.gif, alt=Animation of the use of the fifth lower bead in addition, Use of the 5th lower bead in addition according to the ''Panzhu Suanfa''

File:Panzhu Suanfa subtraction.gif, alt=Animation of the use of the fifth lower bead in subtraction, Use of the 5th lower bead in subtraction according to the ''Panzhu Suanfa''

The beads and rods are often lubricated to ensure quick, smooth motion.

Zhusuan (; literally: "bead calculation") is the knowledge and practices of

Zhusuan (; literally: "bead calculation") is the knowledge and practices of

Suanpan Tutor

- See the steps in addition and subtraction

A Traditional Suan Pan Technique for Multiplication

Hex to Suanpan

*UNESCO video on Chinese Zhusuan on YouTube (Published on Dec 4, 2013)

Zhusuan

{{Calculator navbox Abacus Chinese inventions Science and technology in China

abacus

An abacus ( abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a hand-operated calculating tool which was used from ancient times in the ancient Near East, Europe, China, and Russia, until the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. A ...

of Chinese origin, earliest first known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BCE during the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

, and later, described in a 190 CE book of the Eastern Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

, namely ''Supplementary Notes on the Art of Figures'' written by Xu Yue. However, the exact design of this suanpan is not known.

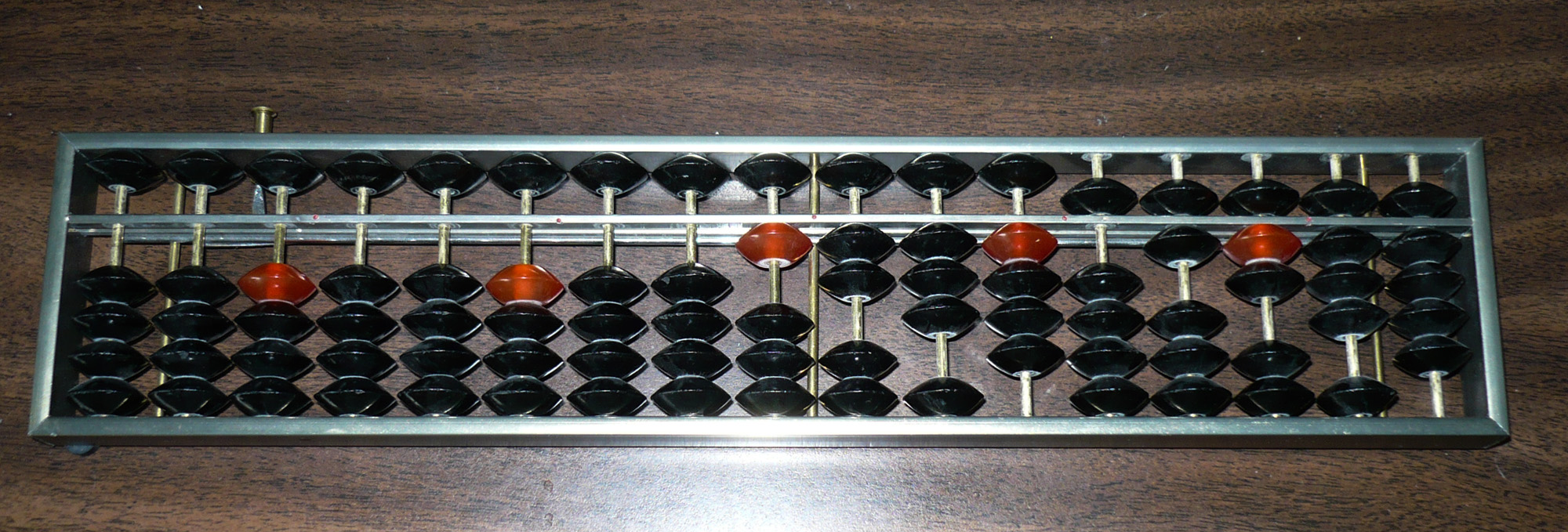

Usually, a suanpan is about 20 cm (8 in) tall and it comes in various widths depending on the application. It usually has more than seven rods. There are two beads on each rod in the upper deck and five beads on each rod in the bottom deck. The beads are usually rounded and made of a hardwood

Hardwood is wood from Flowering plant, angiosperm trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostl ...

. The beads are counted by moving them up or down towards the beam. The suanpan can be reset to the starting position instantly by a quick jerk around the horizontal axis to spin all the beads away from the horizontal beam at the center.

Suanpans can be used for functions other than counting. Unlike the simple counting board

The counting board is the precursor of the abacus, and the earliest known form of a counting device (excluding fingers and other very simple methods). Counting boards were made of stone or wood, and the counting was done on the board with beads, ...

used in elementary schools, very efficient suanpan techniques have been developed to do multiplication

Multiplication is one of the four elementary mathematical operations of arithmetic, with the other ones being addition, subtraction, and division (mathematics), division. The result of a multiplication operation is called a ''Product (mathem ...

, division, addition

Addition (usually signified by the Plus and minus signs#Plus sign, plus symbol, +) is one of the four basic Operation (mathematics), operations of arithmetic, the other three being subtraction, multiplication, and Division (mathematics), divis ...

, subtraction

Subtraction (which is signified by the minus sign, –) is one of the four Arithmetic#Arithmetic operations, arithmetic operations along with addition, multiplication and Division (mathematics), division. Subtraction is an operation that repre ...

, square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that y^2 = x; in other words, a number whose ''square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or y \cdot y) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16 because 4 ...

and cube root

In mathematics, a cube root of a number is a number that has the given number as its third power; that is y^3=x. The number of cube roots of a number depends on the number system that is considered.

Every real number has exactly one real cub ...

operations at high speed.

The modern suanpan has 4+1 beads, colored beads to indicate position and a clear-all button. When the clear-all button is pressed, two mechanical levers push the top row beads to the top position and the bottom row beads to the bottom position, thus clearing all numbers to zero. This replaces clearing the beads by hand, or quickly rotating the suanpan around its horizontal center line to clear the beads by centrifugal force.

History

The word "abacus" was first mentioned by Xu Yue (160–220) in his book ''suanshu jiyi'' (算数记遗), or ''Notes on Traditions of Arithmetic Methods'', in the

The word "abacus" was first mentioned by Xu Yue (160–220) in his book ''suanshu jiyi'' (算数记遗), or ''Notes on Traditions of Arithmetic Methods'', in the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

. As it described, the original abacus had five beads (''suan zhu)'' bunched by a stick in each column, separated by a transverse rod, and arrayed in a wooden rectangle box. One in the upper part represents five and each of four in the lower part represents one. People move the beads to do the calculation.

The long scroll '' Along the River During Qing Ming Festival'' painted by Zhang Zeduan

Zhang Zeduan (; 1085–1145), courtesy name Zhengdao (), was a Chinese painter of the Song dynasty. He lived during the transitional period from the Northern Song to the Southern Song, and was instrumental in the early history of the Chinese la ...

(1085–1145) during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

(960–1279) might contain a suanpan beside an account book and doctor's prescriptions on the counter of an apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is an Early Modern English, archaic English term for a medicine, medical professional who formulates and dispenses ''materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in Brit ...

. However, the identification of the object as an abacus is a matter of some debate.

Zhusuan was an abacus invented in China at the end of the 2nd century CE and reached its peak during the period from the 13th to the 16th century CE. In the 13th century, Guo Shoujing

Guo Shoujing (, 1231–1316), courtesy name Ruosi (), was a Chinese astronomer, hydraulic engineer, mathematician, and politician of the Yuan dynasty. The later Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591–1666) was so impressed with the preserved astro ...

(郭守敬) used Zhusuan to calculate the length of each orbital year and found it to be 365.2425 days. In the 16th century, Zhu Zaiyu

Zhu Zaiyu (; 1536 – 19 May 1611) was a Chinese scholar, mathematician and music theorist. He was a prince of the Chinese Ming dynasty. In 1584, Zhu innovatively described the equal temperament via accurate mathematical calculation.

無� ...

(朱載堉) calculated the musical Twelve-interval Equal Temperament using Zhusuan. And again in the 16th century, Wang Wensu (王文素) and Cheng Dawei

Cheng Dawei (程大位, 1533–1606), also known as Da Wei Cheng or Ch'eng Ta-wei, was a Chinese mathematician and writer who was known mainly as the author of '' Suanfa Tongzong (算法統宗)'' (''General Source of Computational Methods''). He ...

(程大位) wrote respectively Principles of Algorithms and General Rules of Calculation, summarizing and refining the mathematical algorithms of Zhusuan, thus further boosting the popularity and promotion of Zhusuan. At the end of the 16th century, Zhusuan was introduced to neighboring countries and regions.

A 5+1 suanpan appeared in the Ming dynasty, an illustration in a 1573 book on suanpan showed a suanpan with one bead on top and five beads at the bottom.

The evident similarity of the Roman abacus

The Ancient Romans developed the Roman hand abacus, a portable, but less capable, base-10 version of earlier abacuses like those that were used by the Greeks and Babylonians.

Origin

The Roman abacus was the first portable calculating device for ...

to the Chinese one suggests that one may have inspired the other, as there is strong evidence of a trade relationship between the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

and China. However, no direct connection can be demonstrated, and the similarity of the abaci could be coincidental, both ultimately arising from counting with five fingers per hand. Where the Roman model and Chinese model (like most modern Japanese) has 4 plus 1 bead per decimal place, the old version of the Chinese suanpan has 5 plus 2, allowing less challenging arithmetic algorithms. Instead of running on wires as in the Chinese and Japanese models, the beads of Roman model run in grooves, presumably more reliable since the wires could be bent.

Another possible source of the suanpan is Chinese counting rods

Counting rods (筭) are small bars, typically 3–14 cm (1" to 6") long, that were used by mathematicians for calculation in ancient East Asia. They are placed either horizontally or vertically to represent any integer or rational number.

...

, which operated with a place value decimal system with empty spot as zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. Adding (or subtracting) 0 to any number leaves that number unchanged; in mathematical terminology, 0 is the additive identity of the integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and compl ...

.

Although sinologist Nathan Sivin

Nathan Sivin (11 May 1931 – 24 June 2022), also known as Xiwen (), was an American sinologist, historian, essayist, educator, and writer. He taught first at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then at the University of Pennsylvania until his r ...

claimed that the abacus, with its limited flexibility, "was useless for the most advanced algebra", and suggested that "the convenience of the abacus" may have paradoxically stymied mathematical innovation from the 14th to 17th centuries, Roger Hart counters that the abacus in fact facilitated new developments during that time, such as Zhu Zaiyu

Zhu Zaiyu (; 1536 – 19 May 1611) was a Chinese scholar, mathematician and music theorist. He was a prince of the Chinese Ming dynasty. In 1584, Zhu innovatively described the equal temperament via accurate mathematical calculation.

無� ...

's treatises on musical equal temperament, for which he used nine abacuses to calculate to twenty-five digits.

Beads

There are two types of beads on the suanpan, those in the lower deck, below the separator beam, and those in the upper deck above it. The ones in the lower deck are sometimes called ''earth beads'' or ''water beads'', and carry a value of 1 in their column. The ones in the upper deck are sometimes called ''heaven beads'' and carry a value of 5 in their column. The columns are much like the places in Indian numerals: one of the columns, usually the rightmost, represents the ones place; to the left of it are the tens, hundreds, thousands place, and so on, and if there are any columns to the right of it, they are the tenths place, hundredths place, and so on. The suanpan is a 2:5 abacus: two heaven beads and five earth beads. If one compares the suanpan to the soroban which is a 1:4 abacus, one might think there are two "extra" beads in each column. In fact, to represent decimal numbers and add or subtract such numbers, one strictly needs only one upper bead and four lower beads on each column. Some "old" methods to multiply or divide decimal numbers use those extra beads like the "Extra Bead technique" or "Suspended Bead technique". The most mysterious and seemingly superfluous fifth lower bead, likely inherited from counting rods as suggested by the image above, was used to simplify and speed up addition and subtraction somewhat, as well as to decrease the chances of error. Its use was demonstrated, for example, in the first book devoted entirely to suanpan: ''Computational Methods with the Beads in a Tray'' (''Pánzhū Suànfǎ'' 盤珠算法) by Xú Xīnlǔ 徐心魯 (1573, Late Ming dynasty).

A simplify explanation on how to use the 5th beads is show

The most mysterious and seemingly superfluous fifth lower bead, likely inherited from counting rods as suggested by the image above, was used to simplify and speed up addition and subtraction somewhat, as well as to decrease the chances of error. Its use was demonstrated, for example, in the first book devoted entirely to suanpan: ''Computational Methods with the Beads in a Tray'' (''Pánzhū Suànfǎ'' 盤珠算法) by Xú Xīnlǔ 徐心魯 (1573, Late Ming dynasty).

A simplify explanation on how to use the 5th beads is showhere

The following two animations show the details of this particular usage:

Calculating on a suanpan

At the end of a decimal calculation on a suanpan, it is never the case that all five beads in the lower deck are move. Compared with the Chinese abacus, Japanese Soroban can accommodate up to 9 in each digit rod and when it becomes 10, the digit rod changes that will visualise the Decimal system bead in the top deck takes their place. Similarly, if two beads in the top deck are pushed down, they are pushed back up, and one carry bead in the lower deck of the next column to the left is moved up. The result of the computation is read off from the beads clustered near the separator beam between the upper and lower deck. In the past, the chinese used the traditional system of measurements called the ''Shì yòng zhì'' (市用制) for its suanpan. In ''Shì yòng zhì'' (市用制), the unit of weight the ''jīn'' (斤), was defined as 16 ''liǎng'' (兩), which made it necessary to perform calculations in hexadecimal. The Suanpan can accommodate up to 15 in each digit rod and when it becomes 16, the digit rod changes that will visualise the Hexadecimal system. That is the reason why the Japanese Soroban's 4 earth beads(when value is 0) is one bead apart from the beam while the suanpan's 5 earth beads(when value is 0) are 2 beads apart from its beam.Division

There exist different methods to perform division on the suanpan. Some of them require the use of the so-called "Chinese division table". The two most extreme beads, the bottommost ''earth bead'' and the topmost ''heaven bead'', are usually not used in addition and subtraction. They are essential (compulsory) in some of the multiplication methods (two of three methods require them) and division method (special division table, ''Qiuchu'' 九歸, one amongst three methods). When the intermediate result (in multiplication and division) is larger than 15 (fifteen), the second (extra) upper bead is moved halfway to represent ten (xuanchu, suspended). Thus the same rod can represent up to 20 (compulsory as intermediate steps in traditional suanpan multiplication and division). The mnemonics/readings of the Chinese division method iuchuhas its origin in the use of bamboo sticks housuan which is one of the reasons that many believe the evolution of suanpan is independent of the Roman abacus. This Chinese division method (i.e. with ''division table'') was not in use when the Japanese changed their abacus to one upper bead and four lower beads in about the 1920s.Decimal system

This 4+1 abacus works as a bi-quinary based number system (the 5+2 abacus is similar but not identical to bi-quinary) in which carries and shifting are similar to thedecimal

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers (''decimal fractions'') of th ...

number system. Since each rod represents a digit in a decimal number, the computation capacity of the suanpan is only limited by the number of rods on the suanpan. When a mathematician runs out of rods, another suanpan can be added to the left of the first. In theory, the suanpan can be expanded indefinitely in this way.

The suanpan's extra beads can be used for representing decimal numbers, adding or subtracting decimal numbers, caching carry operations, and base sixteen (hexadecimal) fractions.

Zhusuan

Zhusuan (; literally: "bead calculation") is the knowledge and practices of

Zhusuan (; literally: "bead calculation") is the knowledge and practices of arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

calculation

A calculation is a deliberate mathematical process that transforms a plurality of inputs into a singular or plurality of outputs, known also as a result or results. The term is used in a variety of senses, from the very definite arithmetical ...

through the suanpan. In the year 2013, it has been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Zhusuan is named after the Chinese name of abacus, which has been recognised as one of the Fifth Great Innovation in China While deciding on the inscription, the Intergovernmental Committee noted that "Zhusuan is considered by Chinese people as a cultural symbol of their identity as well as a practical tool; transmitted from generation to generation, it is a calculating technique adapted to multiple aspects of daily life, serving multiform socio-cultural functions and offering the world an alternative knowledge system." The movement to get Chinese Zhusuan inscribed in the list was spearheaded by Chinese Abacus and Mental Arithmetic Association.

Zhusuan is an important part of the traditional Chinese culture. Zhusuan has a far-reaching effect on various fields of Chinese society, like Chinese folk custom, language, literature, sculpture, architecture, etc., creating a Zhusuan-related cultural phenomenon. For example, ‘Iron Abacus’ (鐵算盤) refers to someone good at calculating; ‘Plus three equals plus five and minus two’ (三下五除二; +3 = +5 − 2) means quick and decisive; ‘3 times 7 equals 21’ indicates quick and rash; and in some places of China, there is a custom of telling children's fortune by placing various daily necessities before them on their first birthday and letting them choose one to predict their future lives. Among the items is an abacus, which symbolizes wisdom and wealth.

Modern usage

Suanpan arithmetic was still being taught in school inHong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

as recently as the late 1960s, and in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

into the 1990s. In some less-developed industry, the suanpan (abacus) is still in use as a primary counting device and back-up calculating method. However, when handheld calculator

An electronic calculator is typically a portable electronic device used to perform calculations, ranging from basic arithmetic to complex mathematics.

The first solid-state electronic calculator was created in the early 1960s. Pocket-si ...

s became readily available, school children's willingness to learn the use of the suanpan decreased dramatically. In the early days of handheld calculators, news of suanpan operators beating electronic calculators in arithmetic competitions in both speed and accuracy often appeared in the media. Early electronic calculators could only handle 8 to 10 significant digits, whereas suanpans can be built to virtually limitless precision. But when the functionality of calculators improved beyond simple arithmetic operations, most people realized that the suanpan could never compute higher functions – such as those in trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

– faster than a calculator. As digitalised calculators seemed to be more efficient and user-friendly, their functional capacities attract more technological-related and large scale industries in application. Nowadays, even though calculators have become more affordable and convenient, suanpans are still commonly used in China. Many parents still tend to send their children to private tutors or school- and government-sponsored after school activities to learn bead arithmetic as a learning aid and a stepping stone to faster and more accurate mental arithmetic

Mental calculation (also known as mental computation) consists of arithmetical calculations made by the mind, within the brain, with no help from any supplies (such as pencil and paper) or devices such as a calculator. People may use mental calc ...

, or as a matter of cultural preservation. Speed competitions are still held.

Suanpans are still widely used elsewhere in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, as well as in a few places in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. With its historical value, it has symbolized the traditional cultural identity

Cultural identity is a part of a person's identity (social science), identity, or their self-conception and self-perception, and is related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, social class, generation, Locality (settlement), locality, gender, o ...

. It contributes to the advancement of calculating techniques and intellectual development, which closely relate to the cultural-related industry like architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

and folk customs. With their operational simplicity and traditional habit, Suanpans are still generally in use in small-scale shops.

In mainland China, formerly accountants and financial personnel had to pass certain graded examinations in bead arithmetic before they were qualified. Starting from about 2002 or 2004, this requirement has been entirely replaced by computer accounting.

Notes

See also

*Abacus

An abacus ( abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a hand-operated calculating tool which was used from ancient times in the ancient Near East, Europe, China, and Russia, until the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. A ...

*Counting rods

Counting rods (筭) are small bars, typically 3–14 cm (1" to 6") long, that were used by mathematicians for calculation in ancient East Asia. They are placed either horizontally or vertically to represent any integer or rational number.

...

*Soroban

The is an abacus developed in Japan. It is derived from the History of Science and Technology in China, ancient Chinese suanpan, imported to Japan in the 14th century. Like the suanpan, the soroban is still used today, despite the proliferation ...

References

* * *External links

Suanpan Tutor

- See the steps in addition and subtraction

A Traditional Suan Pan Technique for Multiplication

Hex to Suanpan

*UNESCO video on Chinese Zhusuan on YouTube (Published on Dec 4, 2013)

Zhusuan

{{Calculator navbox Abacus Chinese inventions Science and technology in China